Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Diffusion-weighted imaging may aid in distinguishing aggressive chordoma from nonaggressive chordoma. This study explores the prognostic role of the apparent diffusion coefficient in chordomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Sixteen patients with residual or recurrent chordoma were divided postoperatively into those with an aggressive tumor, defined as a growing tumor having a doubling time of <1 year, and those with a nonaggressive tumor on follow-up MR images. The ability of the ADC to predict an aggressive tumor phenotype was investigated by receiver operating characteristic analysis. The prognostic role of ADC was assessed using a Kaplan-Meier curve with a log-rank test.

RESULTS:

Seven patients died during a median follow-up of 48 months (range, 4–126 months). Five of these 7 patients were in the aggressive tumor group, and 2 were in the nonaggressive tumor group. The mean ADC was significantly lower in the aggressive tumor group than in the nonaggressive tumor group (P = .002). Receiver operating characteristic analysis showed that a cutoff ADC value of 1.494 × 10−3 × mm2/s could be used to diagnose aggressive tumors with an area under the curve of 0.983 (95% CI, 0.911–1.000), a sensitivity of 1.000 (95% CI, 0.541–1.000), and a specificity of 0.900 (95% CI, 0.555–0.998). Furthermore, a cutoff ADC of ≤1.494 × 10−3 × mm2/s was associated with a significantly worse prognosis (P = .006).

CONCLUSIONS:

Lower ADC values could predict tumor progression in postoperative chordomas.

Chordoma is a rare bone tumor arising from notochordal remnants in the skull base, spine, or sacrococcygeal region.1 The 2013 World Health Organization classification of bone tumors identifies 3 subgroups of chordoma: classic chordoma not otherwise specified, chondroid, and dedifferentiated.1 Dedifferentiated chordoma arises in a pre-existing low-grade chordoma and has the worst prognosis, so it is important to identify dedifferentiated or aggressive components when evaluating chordomas.2

DWI could potentially be used to distinguish chordoma from chondrosarcoma because the ADC values for chordoma are lower than those for chondrosarcoma.3,4 Moreover, the ADC values are lower in aggressive chordomas than in classic chordomas, suggesting that ADC may be useful for classifying chordomas into subcategories according to aggressiveness.4 Hanna et al5 suggested that a low T2 component in chordoma represented aggressive chordoma. Classic and chondroid chordomas contain stromal mucin and chondroid matrix, respectively, which produce an increased T2 signal and a higher ADC, whereas an aggressive tumor contains less stroma with high cellularity and a lower ADC.4 However, there is sparse literature describing the relationship between the MR imaging signal characteristics of chordoma and prognosis.

Surgical resection is the standard therapy for chordoma, though there have been recent advances in radiation therapy (RT).6–11 En bloc surgical resection with negative margins and no intraoperative spill is associated with a reduced rate of local recurrence. However, the location of the chordoma may limit the ability to perform a gross total resection.8,10 After the first surgical resection, adjuvant RT is often used to reduce the likelihood of recurrence and improve the prognosis.12,13

After an initial operation and RT, most patients undergo serial imaging to detect recurrence. It is important to recognize recurrence early to ensure adequate salvage therapy.6,13 Although radiologic evaluation is important in oncology, assessment of tumor progression or response to treatment is based on changes in the residual tumor size on imaging.14 ADC can identify further characteristics of many tumors with malignant potential.15

We hypothesized that recurrent or residual chordoma that acquires aggressive features with time also shows a decrease in the ADC value. The aim of this study was to explore the role of the ADC as a predictor of outcome in patients with chordomas.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This retrospective study was approved by the University of Iowa institutional review board. The need for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the research. We searched our data base from 2000 to 2016 using the search term “chordoma” and identified 31 patients (mean age, 46.0 ± 21.0 years; range, 7–88 years; 18 males, 13 females) with histopathologically proved chordoma. Five patients were diagnosed with chondroid chordoma, and 26, with classic chordoma. The primary sites of the chordomas were the clivus (n = 16), cervical spine (n = 7), thoracic spine (n = 1), lumbar spine (n = 3), sacrococcygeal region (n = 3), and subarachnoid space in the posterior fossa (n = 1). We included patients with residual or recurrent tumors after the initial therapies for analysis during follow-up periods. Thirteen of the 31 patients had no recurrent or residual tumor or did not undergo >1 MR imaging examination during the follow-up period, so they were excluded from the study. Eighteen of the 31 patients had residual or recurrent chordoma. A “residual tumor” was defined as an expansile mass in the operative bed with contrast enhancement that included high-signal components on T2-weighted imaging after incomplete resection without additional resection within 3 months from the first resection (n = 12). Because the first resection was performed to make a histologic diagnosis in some patients, a subsequent radical resection followed. A “recurrent tumor” was defined as a new expansile mass at or around the previous surgical site on MR imaging, which implied a residual tumor on histopathology (n = 4; On-line Fig 1). MR imaging data for 2 patients were inadequate for analysis because of artifacts or incomplete scan sequences, leaving 16 patients (mean age, 55.3 ± 19.8 years; range, 17–77 years; 12 males, 4 females) with longitudinal follow-up data available for analysis.

A pathologist reviewed the available pathologic material for the 16 patients and confirmed the diagnoses as chondroid chordoma (n = 5) and classic chordoma (n = 11): In 1 patient, the classic chordoma had aggressive features (necrosis, mitotic activity, and cellular pleomorphism), but they were not sufficient for it to be categorized as a dedifferentiated chordoma.

Gross total resection was reported at the first operation in 2 patients, and incomplete resection, in 14 patients. Thirteen of the 16 patients underwent postsurgical RT (photon RT in 11 patients; radiation doses were unknown in 2 patients), 2 patients had no RT, and the treatment was unknown in 1 patient.

Analysis of MR Imaging Data

MR imaging examinations were performed using 1.5T MR imaging scanners (Magnetom Symphony, Avanto, or Espree; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The following parameters were used for the head: spin-echo T2-weighted imaging (TR, 3790–6270 ms; TE, 80–107 ms; FOV, 240 mm; matrix size, 256 × 240; slice thickness, 4–6 mm with 10%–20% interval gaps; parallel imaging factor, 2); precontrast and postcontrast fat-saturated T1-weighted imaging (TR, 413–587 ms; TE, 8.4–12 ms; FOV, 240 mm; matrix size, 256 × 240; slice thickness, 4–6 mm with 10%–20% interval gaps; parallel imaging factor, 2); and echo-planar DWI (TR, 2200–5600 ms; TE, 73–89 ms; FOV, 240 mm; matrix size, 128 × 128; slice thickness, 5 mm with 10%–20% interval gaps; b-value = 0 and 1000 s/mm2; 3 or 12 diffusion directions; parallel imaging factor, 3). The following parameters were used for the spinal and sacral regions: spin-echo T2-weighted imaging (TR, 4000–7280 ms; TE, 101–108 ms; FOV, 220 mm [mobile spine] to 300 [pelvis] mm; matrix size, 240 × 200; parallel imaging factor, 2); precontrast and postcontrast fat-saturated T1-weighted imaging (TR, 507–611 ms; TE, 6.6–9.5 ms; FOV, 220 mm [mobile spine] to 300 [pelvis] mm; matrix size, 220 × 200; slice thickness, 4–6 mm with 10%–20% interval gaps; parallel imaging factor, 2); and echo-planar DWI (TR, 4100–9300 ms; TE, 78–96 ms; FOV, 220 mm [mobile spine] to 300 [pelvis] mm; matrix size, 128 × 128–192 × 145; parallel imaging factor, 1–2; slice thickness, 5 mm with 10%–20% interval gaps; b-value = 0 and 1000 s/mm2; 3 diffusion directions). ADC maps were generated according to a monoexponential fitting model using commercially available software (Olea Sphere, Version 3.0; Olea Medical, La Ciotat, France).

During follow-up, all 16 patients underwent at least 2 MR imaging scans. The 2 MR imaging series were selected on the basis of the following rules: 1) The first MR imaging occurred at least 6 months after RT; 2) there was neither surgical resection nor RT between the first and second MR imaging; 3) DWI was available, in addition to at least T1- or T2-weighted images; and 4) if there were >2 MR imaging scans after the first MR imaging, the second MR imaging was selected as the scan that occurred approximately 1 year after the first MR imaging.

Two neuroradiologists independently outlined the ROI in freehand for the 2 MR imaging scans—that is, they outlined the whole volume of the chordoma on the ADC maps, while checking the coregistered T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images, in addition to using Olea Sphere, Version 3.0, software to avoid cystic components and necrosis (On-line Fig 2). The mean ADC values and tumor volume were calculated on the basis of the summation of the ROIs.16 The volume change ratios were calculated using the following formula:

where Vol1st is the tumor volume on the first MR imaging scan and Vol2nd is the tumor volume on the second MR imaging scan.

We classified patients into 2 groups based on the volume change ratio and tumor growth rate. To assess the tumor growth rate, we calculated the tumor doubling time in patients with a positive volume change ratio (ie, growing tumors) using the Schwartz formula17:

where t is the time interval between the 2 MR imaging scans.

We defined growing tumors with a doubling time of <1 year as aggressive tumors and those with a doubling time of ≥1 year as nonaggressive tumors.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 22 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York). The tumor measurements were assessed for interobserver reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient, and mean values were used for further evaluation. On the first postoperative MR imaging, we compared mean ADC values, tumor volume, patient age at the time of the first surgical resection, time interval between the surgical resection and the first MR imaging, time interval between the first and second MR imaging examinations, number of surgical resections, patient sex, histopathology, location of the tumor, and volume change ratio between the 2 groups using the Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher exact test. We assessed the cutoff ADC on the first MR imaging to predict aggressiveness and receiver operating characteristic analysis to assess outcomes in the aggressive tumor group. The optimal cutoff value in the receiver operating characteristic analysis was determined as a value to maximize the Youden index.18 Kaplan-Meier curves for survival were compared using log-rank tests with the following variables: the mean ADC cutoff value in the receiver operating characteristic analysis and the following items previously reported to be prognostic factors: age at the time of the first operation,19 number of previous surgical resections,19,20 tumor volume,2,19 histopathology,21 tumor location,2 and adjuvant radiation therapy.16 The study end point was survival. The survival period was calculated as the duration from the first MR imaging scan to the date of death or last follow-up in the censored living patients. Moreover, a Kaplan-Meier curve with a log-rank test was performed as a reference at the second MR imaging in the 2 groups. A 2-tailed P value <.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Demographic, Clinical, and Radiographic Data

The intraclass correlation coefficients for interobserver reliability between the 2 readers were 0.922 (95% CI, 0.843–0.963) for the mean ADC and 0.974 (95% CI, 0.946–0.988) for the tumor volume. Six of the 16 patients had aggressive tumors, and 10 had nonaggressive tumors. Seven of the 16 patients died during the study period (5 were in the aggressive-tumor group and died of complications of their chordomas; 2 were in the nonaggressive tumor group and died of concurrent diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [n = 1] and an unknown cause [n = 1]). The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Patient demographic and clinical characteristicsa

| Aggressive Tumor | Nonaggressive Tumor | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 6 | 10 | |

| Volume change ratio | 14.4 ± 21.0 (−2.18–17.2) | 0.463 ± 1.135 (−1.40–3.78) | .003 |

| Doubling time (mo) | 5.77 ± 4.03 (0.73–10.8) | NA | |

| Age at first operation (yr) | 54.3 ± 9.9 | 45.8 ± 24.3 | .713 |

| Location of tumor (ratio of clival chordoma to all) | 3/6 | 8/10 | .299b |

| Postsurgical RT radiation dose (Gy) | 72.4 ± 33.5 (n = 4) | 74.2 ± 10.9 (n = 7) | .927 |

| Ratio of patients with postsurgical RT to all | 4/6 | 9/10 | .518b |

| Time from first operation to first follow-up MRI (mo) | 62.8 ± 53.3 | 71.4 ± 76.2 | >.99 |

| Time between the 2 follow-up MRIs (mo) | 9.1 ± 5.2 | 18.3 ± 12.5 | .022 |

| No. of surgical resections at first follow-up MRI | 2.00 ± 0.89 | 1.10 ± 0.32 | .056 |

| Sex (M/F) | 5:1 | 7:3 | >.99b |

| Histopathology (ratio of classic chordoma to all chordomas) | 6/6 | 5/10 | .093b |

| Mean ADC (×10−3 × mm2/s) | 1.055 ± 0.298 (0.78–1.37) | 1.622 ± 0.139 (1.34–1.65) | <.001 |

| Tumor volume (× 103 × mm3) | 21.2 ± 37.4 (0–60.4) | 3.44 ± 2.38 (0–7.46) | .492 |

Note:—NA indicates not applicable.

Numbers in the table represent mean ± SD. The numbers in parentheses indicate the 95% CIs.

P value was calculated by the Fisher exact test because the data were categoric.

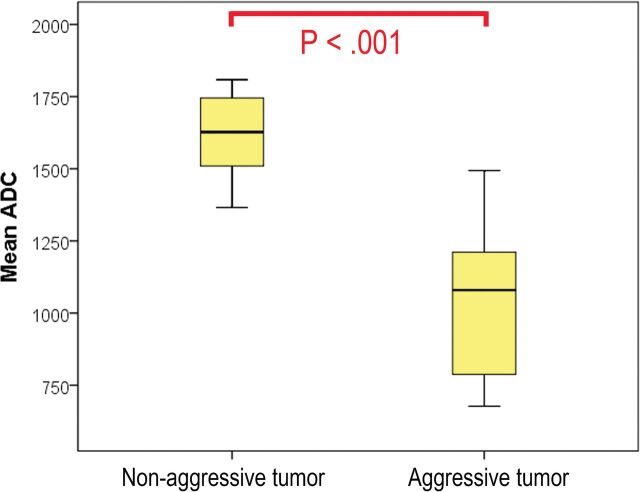

The volume change ratios were significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .003). The mean ADC was significantly lower in the aggressive tumor group than in the nonaggressive tumor group (P < .001; Figs 1–3). The time interval between the 2 MR imaging examinations was significantly shorter in the aggressive tumor group than in the nonaggressive tumor group (P = .022).

Fig 1.

Comparison of mean ADC values between groups with different tumor-progression statuses. There was a significant difference between the 2 groups (P < .001).

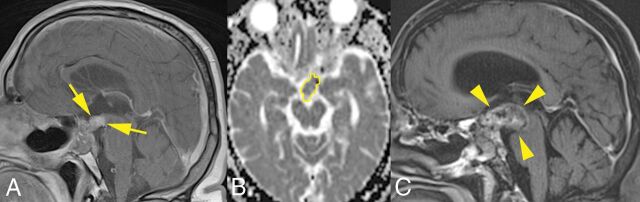

Fig 2.

A 59-year-old man with a recurrent chordoma in the aggressive tumor group. A, Two years after the first surgery, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging shows an expansile mass extending to the suprasellar region (arrows). B, The ROI outlined in yellow on the ADC map represents decreased water diffusivity (ADC = 1.211 × 10−3 × mm2/s). C, Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging obtained 8 months later shows an increase of the mass (volume change ratio, 1.67; arrowheads) with a doubling time of 5.5 months. The patient died of disease 15 months after the second MR imaging examination.

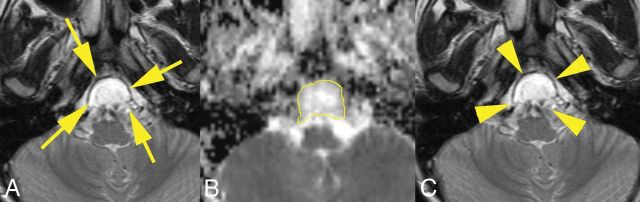

Fig 3.

A 10-year-old boy with a residual chordoma in the nonaggressive tumor group. A, Three years after the first operation, T2-weighted imaging shows an expansile mass in the clivus (arrows). B, The ROI outlined in yellow on the ADC map represents increased water diffusivity (ADC = 1.808 × 10−3 mm2/s). C, The mass was stable on T2-weighted imaging obtained 13 months later (volume change ratio = 0.11; arrowheads) with a doubling time of 10.0 years. He was still alive 7 years after the second MR imaging.

Role of ADC in Predicting Aggressive Tumor at First MRI

Receiver operating characteristic analysis clearly distinguished the aggressive tumor group from the nonaggressive tumor group with a cutoff ADC of 1.494 × 10−3× mm2/s, a sensitivity of 1.000 (95% CI, 0.541–1.000), a specificity of 0.900 (95% CI, 0.555–0.998), and a higher area under the curve of 0.983 (P = .002; 95% CI, 0.911–1.000; Table 2).

Table 2:

ROC plot analysis for ADC values differentiating an aggressive tumor from a nonaggressive tumora

| Aggressive Tumor | |

|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.983 (0.911–1.000) (P = .002) |

| Cutoff ADC value (×10−3 × mm2/s) | 1.494 |

| Sensitivity | 1.000 (0.541–1.000) |

| Specificity | 0.900 (0.555–0.998) |

| Accuracy | 0.938 (0.698–0.998) |

| PPV | 0.857 (0.421–0.996) |

| NPV | 1.000 (0.664–1.000) |

| Positive LR | 10 (1.56–64.2) |

| Negative LR | 0 |

Note:—ROC indicates receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve; LR, likelihood ratio; NA, not available; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Numbers in parentheses indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Predicting Survival for Patients with Chordoma

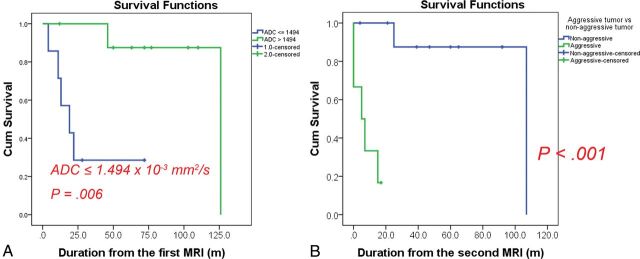

The median follow-up was 48 months (range, 4–126 months). The results for prognostic factors are shown in Table 3. The log-rank test revealed that an ADC below the cutoff of ≤1.494 × 10−3 × mm2/s was associated with a significantly worse prognosis (P = .006, Fig 4A). The log-rank test for the 2 groups at the second MR imaging showed a significantly worse prognosis in the aggressive tumor group than in the nonaggressive tumor group (P < .001, Fig 4B). There was a significant association between ≥2 previous surgical resections and a worse prognosis (P = .002). The other variables did not contribute significantly to survival.

Table 3:

Kaplan-Meier curves for survival using log-rank tests in patients with recurrent chordomas

| Explanatory Variables | Total No. | No. of Events | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate models | |||

| Age at first operation (yr) | .312 | ||

| Younger than 60 | 10 | 5 | |

| 60 or older | 6 | 2 | |

| No. of surgical resections at first MRI | .002 | ||

| 1 | 11 | 3 | |

| ≥2 | 5 | 4 | |

| Tumor volume | .957 | ||

| <3 × 103 × mm3 | 10 | 4 | |

| ≥3 × 103 × mm3 | 6 | 3 | |

| Histopathology | |||

| Chondroid chordoma | 5 | 1 | .346 |

| Classic chordoma | 11 | 6 | |

| Tumor location | .507 | ||

| Clivus | 11 | 5 | |

| Other sites | 5 (C = 1, L = 2, S = 1, other = 1) | 2 | |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy | .172 | ||

| None/unknown | 3 | 2 | |

| Done | 13 | 5 | |

| Mean ADC (for an aggressive tumor) | .006 | ||

| >1.494 × 10−3 × mm2/s | 10 | 2 | |

| ≤1.494 × 10−3 × mm2/s | 6 | 5 |

Note:—C indicates cervical spine; L, lumber spine; S, sacrum.

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves using log-rank tests for survival. A, Graph shows 2 groups based on a cutoff ADC of 1.494 × 10−3 mm2/s at the first MR imaging. The group with the lower ADC had a significantly worse prognosis (P = .006). B, Graph shows the tumor progression rate in the 2 groups at the second MR imaging. The prognosis was significantly worse in the aggressive tumor group than in the nonaggressive tumor group (P < .001). The cutoff ADC value could predict patients with a worse prognosis at the first MR imaging at a mean of 9.1 ± 5.2 months earlier than the second MR imaging. Cum indicates cumulative.

Discussion

Our measurements showed that the interclass correlation coefficients were >0.8, which indicated excellent interobserver reliability.22 In patients with residual postoperative chordoma, the tumor ADC values accurately predicted disease progression as defined by tumor volume change with time. This finding is consistent with that reported by Yeom et al,4 who suggested that poorly differentiated chordomas have a lower ADC value compared with conventional and chondroid chordomas. Aggressive chordoma has a worse prognosis and typically arises in a pre-existing low-grade lesion with or without previous radiation therapy.1,5,23–28 Thus, a lower ADC value in chordomas might correlate with aggressive growth. By measuring ADC coefficients of residual chordomas, we were able to retrospectively identify patients who went on to show tumor progression >9 months later at the second follow-up MR imaging. Moreover, ADC measurement is less technically demanding for measuring tumor volumes.

Our Kaplan-Meier curves for survival using a log-rank test identified a lower ADC value and more surgical resections as significant prognostic factors. The ADC and the number of surgical resections could be confounder factors of each other for survival (On-line Fig 3). Most of the reports related to chordoma evaluated primary chordomas and recurrent chordomas en bloc, but we focused on residual or recurrent chordomas.21,29,30 Ailon et al6 suggested that further complete surgical resection can be considered for local recurrent chordoma, even if the management of recurrent chordoma is challenging and may be palliative. We supposed that follow-up MR imaging using ADC mapping could discriminate small chordomas with an aggressive potential from those without it; this discrimination could allow a short follow-up or early salvage therapy (further surgical resection) that would likely be successful or effective.

RT might affect MR imaging signal evaluation in residual or recurrent tumors.31–33 We did not find any correlation between the ADC values and RT dose or duration from RT to the first MR imaging (On-line Appendix). However, ADC values reflecting the response to treatment might be increased several days after RT or chemotherapy in various types of tumors.31–34 Given that ADC values correlate with cell density,33 the treatment response (with reduction of tumor cell volume) could elevate the ADC, while tumor progression (with proliferation of tumor cells) could decrease it. There is little information concerning MR imaging signal changes in chordomas after RT, particularly after proton or carbon ion RT. Proton or carbon ion RT might become an alternative therapy for unresectable chordoma in the future.20,35,36 We speculate that a reduced ADC during follow-up after RT might predict early recurrence.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was retrospective in nature and included a small population from a single institution. Chordoma is a rare low-grade tumor, so it is difficult to perform large studies in patients with this tumor. Second, because of the long time intervals between datasets, the MR imaging scan parameters were different. Third, we were unable to evaluate the pathology of the tumors in those who died of disease to assess aggressiveness or dedifferentiation in those tumors. Fourth, the time interval between the 2 follow-up MR imaging scans differed between the 2 groups. Fifth, whether 1 year of doubling time was the most appropriate cutoff to separate the aggressive tumor group from the nonaggressive tumor group is unknown. Sixth, there were 2 patients with an unknown RT dose and 1 patient with an unknown RT history, which might have affected the results for our small cohort. Finally, we did not show a significant role for RT in survival. The role of RT might be underestimated because high-dose RT is needed to reduce the risk of recurrence and improve patient prognoses.12,13,37 Further studies are needed to address these issues.

Conclusions

The mean ADC for recurrent or residual chordoma after the first operation could predict a subgroup with likely tumor progression and was significantly lower in the aggressive tumor group than in the nonaggressive tumor group. An ADC ≤1.494 × 10−3 mm2/s could be predictive of the likelihood of rapid disease progression and a worse prognosis. In chordoma with a lower ADC, therefore, it may be prudent to recommend closer follow-up.

Supplementary Material

ABBREVIATION:

- RT

radiotherapy

Footnotes

Disclosures: Tomoaki Sasaki—RELATED: Grant: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Comments: grant No. JP15K19762.

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Grant No. JP15K19762 (T.S.).

References

- 1. Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn P, et al. . WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed Lyon: IARC Press; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chugh R, Tawbi H, Lucas DR, et al. . Chordoma: the nonsarcoma primary bone tumor. Oncologist 2007;12:1344–50 10.1634/theoncologist.12-11-1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Müller U, Kubik-Huch RA, Ares C, et al. . Is there a role for conventional MRI and MR diffusion-weighted imaging for distinction of skull base chordoma and chondrosarcoma? Acta Radiol 2016;57:225–32 10.1177/0284185115574156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yeom KW, Lober RM, Mobley BC, et al. . Diffusion-weighted MRI: distinction of skull base chordoma from chondrosarcoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:1056–61, S1 10.3174/ajnr.A3333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanna SA, Tirabosco R, Amin A, et al. . Dedifferentiated chordoma: a report of four cases arising ‘de novo.’ J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:652–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ailon T, Torabi R, Fisher CG, et al. . Management of locally recurrent chordoma of the mobile spine and sacrum: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41(Suppl 20):S193–98 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gokaslan ZL, Zadnik PL, Sciubba DM, et al. . Mobile spine chordoma: results of 166 patients from the AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor database. J Neurosurg Spine 2016;24:644–51 10.3171/2015.7.SPINE15201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boriani S, Saravanja D, Yamada Y, et al. . Challenges of local recurrence and cure in low grade malignant tumors of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:S48–57 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b969ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boriani S, Bandiera S, Biagini R, et al. . Chordoma of the mobile spine: fifty years of experience. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:493–503 10.1097/01.brs.0000200038.30869.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. York JE, Kaczaraj A, Abi-Said D, et al. . Sacral chordoma: 40-year experience at a major cancer center. Neurosurgery 1999;44:74–79; discussion 79–80 10.1097/00006123-199901000-00041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen KW, Yang HL, Lu J, et al. . Prognostic factors of sacral chordoma after surgical therapy: a study of 36 patients. Spinal Cord 2010;48:166–71 10.1038/sc.2009.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hulen CA, Temple HT, Fox WP, et al. . Oncologic and functional outcome following sacrectomy for sacral chordoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1532–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pennicooke B, Laufer I, Sahgal A, et al. . Safety and local control of radiation therapy for chordoma of the spine and sacrum: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41(Suppl 20):S186–92 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Si MJ, Wang CS, Ding XY, et al. . Differentiation of primary chordoma, giant cell tumor and schwannoma of the sacrum by CT and MRI. Eur J Radiol 2013;82:2309–15 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kabolizadeh P, Chen YL, Liebsch N, et al. . Updated outcome and analysis of tumor response in mobile spine and sacral chordoma treated with definitive high-dose photon/proton radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;97:254–62 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choe J, Lee SM, Lim S, et al. . Doubling time of thymic epithelial tumours on CT: correlation with histological subtype. Eur Radiol 2017;27:4030–36 10.1007/s00330-017-4795-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zukotynski KA, Vajapeyam S, Fahey FH, et al. . Correlation of 18F-FDG PET and MRI apparent diffusion coefficient histogram metrics with survival in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a report from the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium. J Nucl Med 2017;58:1264–69 10.2967/jnumed.116.185389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bettegowda C, Yip S, Lo SL, et al. ; AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor. Spinal column chordoma: prognostic significance of clinical variables and T (brachyury) gene SNP rs2305089 for local recurrence and overall survival. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:405–13 10.1093/neuonc/now156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park L, Delaney TF, Liebsch NJ, et al. . Sacral chordomas: impact of high-dose proton/photon-beam radiation therapy combined with or without surgery for primary versus recurrent tumor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:1514–21 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kayani B, Sewell MD, Tan KA, et al. . Prognostic factors in the operative management of sacral chordomas. World Neurosurg 2015;84:1354–61 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Han X, Suo S, Sun Y, et al. . Apparent diffusion coefficient measurement in glioma: influence of region-of-interest determination methods on apparent diffusion coefficient values, interobserver variability, time efficiency, and diagnostic ability. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017;45:722–30 10.1002/jmri.25405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kayani B, Sewell MD, Hanna SA, et al. . Prognostic factors in the operative management of dedifferentiated sacral chordomas. Neurosurgery 2014;75:269–75; discussion 275 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim SC, Cho W, Chang UK, et al. . Two cases of dedifferentiated chordoma in the sacrum. Korean J Spine 2015;12:230–34 10.14245/kjs.2015.12.3.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Makek M, Leu HJ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma arising in a recurrent chordoma: case report and electron microscopic findings. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 1982;397:241–50 10.1007/BF00496567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Halpern J, Kopolovic J, Catane R. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma developing in irradiated sacral chordoma. Cancer 1984;53:2661–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fukuda T, Aihara T, Ban S, et al. . Sacrococcygeal chordoma with a malignant spindle cell component: a report of two autopsy cases with a review of the literature. Acta Pathol Jpn 1992;42:448–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hruban RH, May M, Marcove RC, et al. . Lumbo-sacral chordoma with high-grade malignant cartilaginous and spindle cell components. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:384–89 10.1097/00000478-199004000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruosi C, Colella G, Di Donato SL, et al. . Surgical treatment of sacral chordoma: survival and prognostic factors. Eur Spine J 2015;24(Suppl 7):912–17 10.1007/s00586-015-4276-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kayani B, Hanna SA, Sewell MD, et al. . A review of the surgical management of sacral chordoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:1412–20 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hong X, Liu L, Wang M, et al. . Quantitative multiparametric MRI assessment of glioma response to radiotherapy in a rat model. Neuro Oncol 2014;16:856–67 10.1093/neuonc/not245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morse DL, Galons JP, Payne CM, et al. . MRI-measured water mobility increases in response to chemotherapy via multiple cell-death mechanisms. NMR Biomed 2007;20:602–14 10.1002/nbm.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chenevert TL, Stegman LD, Taylor JM, et al. . Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging: an early surrogate marker of therapeutic efficacy in brain tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:2029–36 10.1093/jnci/92.24.2029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jordan BF, Runquist M, Raghunand N, et al. . Dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion MRI show rapid and dramatic changes in tumor microenvironment in response to inhibition of HIF-1alpha using PX-478. Neoplasia 2005;7:475–85 10.1593/neo.04628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Imai R, Kamada T, Araki N. Carbon ion radiation therapy for unresectable sacral chordoma: an analysis of 188 cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;95:322–27 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Uhl M, Welzel T, Jensen A, et al. . Carbon ion beam treatment in patients with primary and recurrent sacrococcygeal chordoma. Strahlenther Onkol 2015;191:597–603 10.1007/s00066-015-0825-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choy W, Terterov S, Kaprealian TB, et al. . Predictors of recurrence following resection of intracranial chordomas. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:1792–96 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.