Abstract

Objective:

In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 47,600 deaths as a result of opioid overdose in the United States. In an effort to reduce these deaths, California passed legislation providing pharmacists with the ability to furnish naloxone without a prescription. Our study examined pharmacies in San Francisco that furnished naloxone and provide guidance for pharmacies seeking to develop similar programs. The study aims were to (1) identify the legal, structural, social-environmental, and financial components of a pharmacy model that allows for successful naloxone distribution, (2) evaluate the attitudes and beliefs of pharmacy staff members towards patients receiving or requesting naloxone and (3) assess relationships between these attitudes and beliefs and naloxone furnishing at the pharmacy.

Design and setting:

This cross-sectional study used a series of semi-structured interviews of pharmacy staff in San Francisco conducted April-October 2019. Through a thematic, inductive analysis of collected data, emerging themes were mapped onto the primary study aims.

Participants, outcomes, and results:

We interviewed 14 pharmacists and pharmacy technicians at four community pharmacies. We identified four factors for success in implementing a naloxone furnishing protocol: administrative-led efforts, pharmacist-led efforts, increasing pharmacist engagement, and increasing patient engagement. Respondents also discussed the approaches they used to overcome previously identified barriers: cost, time, expectations of unwanted clientele, and patient feelings of stigma.

Conclusion:

Pharmacist approaches to implementing naloxone furnishing had common features across locations, suggesting many of these strategies could be replicated in other community pharmacies.

Keywords: Naloxone, Public health, Pharmacies

Introduction

In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 46,802 deaths resulting from opioid overdoses in the United States.1 Over the prior 18 years, the CDC reported that deaths from opioid overdose, particularly synthetic opioids, had been trending upward.1 In California, nearly 2,200 opioid overdose deaths were reported in 2017, an increase of over 8% compared to the previous reported year.2

Opioids bind to the μ-opioid receptor affecting the central nervous system. Excess opioids in an overdose event cause respiratory depression, leading to cardiac arrest from hypoxia.3 The current therapy to address opioid overdose is administration of naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist medication that reverses opioid-induced respiratory depression with minimal adverse effects.4 Naloxone has served as a pivotal agent in combatting opioid overdose deaths and can be supplied by inhalation or injection.4,5 Public health efforts introduced by community organizations and through state legislation have increased public access and engagement with naloxone, resulting in decreased mortality.6,7 However, the continuing, unacceptably high level of overdoses suggests that greater efforts are needed to reduce these deaths.

The accessibility of community pharmacies and the role of pharmacists as trusted health professionals place them in an ideal position to take on harm reduction efforts and increased responsibilities for opioid overdose. Since the 1990s, pharmacies have provided sterile syringes to reduce blood-borne diseases, such as hepatitis C and HIV.8 Legislators across multiple states have recognized the significant role and potential of pharmacists in increasing public access to take-home naloxone.6 In 2014, California passed Assembly Bill (A.B.) 1535 providing pharmacists with the legal authority to screen, furnish, and provide opioid overdose education without a need for a prescription from a physician, using a statewide naloxone standing order; this process is referred to as furnishing.9 Shortly thereafter, the California Board of Pharmacy adopted protocols for pharmacists to furnish naloxone. Public health departments and pharmacies, such as San Francisco’s Community Behavioral Health Service (CBHS) pharmacy, were in a prime position to implement naloxone furnishing because they operate as safety net programs and focus on care for high risk individuals, many of whom have been diagnosed with opioid use disorders.

Despite the passage of A.B. 1535, many California pharmacists and pharmacies have yet to implement a naloxone furnishing program to provide take-home naloxone prescriptions.10 Pharmacists and pharmacies that have established a naloxone furnishing protocol have encountered barriers in the implementation of such protocols. Previous studies have identified barriers ranging from the stigma perceived by patients, to concerns expressed by pharmacists about “undesirable patients” to high out-of-pocket costs for naloxone.11–17 Nonetheless, several pharmacies and pharmacists have reported that implementation of naloxone furnishing is feasible and effective in a community pharmacy setting.18

While multiple studies have identified barriers to implementing naloxone furnishing programs, there is limited information on factors that lead to successful implementation. This gap in understanding hinders pharmacists’ ability to replicate and improve upon existing naloxone furnishing programs. The National Institute on Drug Abuse described this situation on its website, “A great tragedy of the opioid crisis is that so many effective tools already exist but are not being deployed effectively in communities that need them.”19

This study examined four California community pharmacies in San Francisco that had created a naloxone furnishing program, in order to gain insight and understanding into ways community pharmacists can successfully develop their own naloxone furnishing programs. This study aims were to (1) identify the legal, structural, social-environmental, and financial components of a pharmacy model that allows for successful implementation of a naloxone distribution program, (2) evaluate the attitude and beliefs of pharmacy staff towards patients receiving or requesting naloxone, and (3) determine whether those attitudes and beliefs influence naloxone furnishing at the pharmacy. We anticipated that successful naloxone furnishing was multifactorial, based on an effective pharmacy model and an empathetic attitude of staff towards their patient population, and that these factors could be identified for replication in other community pharmacies. These findings could improve public health outcomes by reducing mortality rates caused by opioid use.

Methods

Design:

This cross-sectional study relied on a qualitative approach, comprised of on-site observations combined with a series of semi-structured interviews of community pharmacy staff working in San Francisco, California.20,21 The study was deemed exempt by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board on January 21, 2019 (#18–26309).

Setting:

We selected community pharmacies in San Francisco for this study due to the increase in opioid overdose events in San Francisco and active involvement by the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) in seeking to reduce them.22 We used the Community Behavioral Health Service (CBHS) pharmacy operated by SFDPH to represent a “best practices” site. Three local community pharmacies were used as comparison cases, reflecting that most of the general population primarily visits chain pharmacies.

Sample:

We sampled respondents from four pharmacies in San Francisco that had established and implemented naloxone furnishing programs. Successful implementation was defined by having furnished an average of at least one naloxone unit per month. Key informants, including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and pharmacy managers or directors, were interviewed at participating sites.

Participant Recruitment:

After identification of the four pharmacies, pharmacy managers or directors of CBHS pharmacy and chain pharmacies were initially approached by telephone or in person by an investigator and informed of the study’s objectives. If respondents expressed interest, we provided study information, including the methodology, interview topics, expectations of participants, risk and benefits, and a consent form. For those that consented to participate, we sought approval from the pharmacy’s administration to interview them, and to identify other potential participants using snowball sampling at the same site. The recruitment and interview period began in April 2019 and concluded in October 2019.

Data Collection:

A semi-structured interview guide consisting of 23 open-ended questions with potential follow-up questions and prompts for elaboration was used for pharmacy staff interviews (see Supplement). Each interview was conducted on-site and ranged from 15–60 minutes. Exploratory points of discussion were developed with reference to existing research on naloxone distribution and included;

legal, structural, social-environmental, and financial components regarding the development and implementation of the naloxone furnishing program

description of naloxone furnishing process

pharmacy staff perception of the naloxone furnishing program’s effectiveness, advantages, disadvantages, and barriers

pharmacy staff attitude towards clientele requesting take-home naloxone

pharmacy staff recommendations for replication or improvement of the naloxone furnishing model.

An observational session was conducted at CBHS pharmacy by one author (AN) which focused on the naloxone furnishing process, interaction between pharmacy staff and clientele, and pharmacy staff collaboration. Observational data collection ceased once at least one naloxone furnishing was observed. Observational sessions were also attempted at the comparison chain pharmacies, however due to low frequency and predictability of naloxone furnishing events, no observational data were collected at these locations.

Data Management, Measures, and Analysis:

Interviews with pharmacy staff were audio recorded, transcribed, and de-identified by assigning each participant a number. Observational data were summarized after each session. As credibility checks we used triangulation (interviews combined with observational data), prolonged contact, and sought saturation in responses.23,24 All data collected were stored on a HIPAA-protected server and analyzed using Atlas.ti 8. We coded the transcripts inductively using thematic analysis. The collected data were first coded through a structural (or utilitarian) coding method and any emerging themes were noted.25 The themes were then organized with respective supporting quotations or observational report under one of the three study aims (logistical organization, perception and attitudes, and workflow). Interviewed participants were de-identified and separate subgroup analysis were conducted on pharmacy staff to assess demographics, level of education, and occupational environment. We used observational findings from CBHS to complement interview reports where relevant.

Initial coding and analysis was completed by one investigator (AN) and to assess validity, was then reviewed by the other authors (DA, TK).23,24 Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results:

A total of 14 interviews were conducted between April-October 2019 incorporating pharmacists and pharmacy technicians from CBHS pharmacy and 3 comparator pharmacies representing CBHS, Safeway, and Walgreens pharmacies. Ten respondents were from CBHS pharmacy (8 pharmacists and 2 technicians) and four were from chain pharmacies (all pharmacists). The CBHS pharmacists had been in practice for an average of 16 years, the chain pharmacists 5 years. Compared to chain pharmacies, CBHS had fewer staff members and filled fewer prescriptions (100/day versus 250–600/day), however a much higher share of prescriptions were for naloxone (89/month versus 1–15/month). Of the pharmacists interviewed at CBHS pharmacy, 3 had completed psychiatric residencies or fellowships in behavioral health. None of the pharmacists interviewed at a chain pharmacy had completed additional post-doctoral training (Table 1).

Table 1:

Study Characteristics of Pharmacists and Pharmacies

| Interviewed Participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| CBHS Pharmacy | Chain Pharmacies | |

| Pharmacists | 8 (80%) | 4 (100%) |

| Pharmacy Technicians | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Female | 9 (90%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pharmacist’s years of experience | 1–39 (mean: 16) | 3–8 (mean: 5) |

| Residency Completed | 3 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pharmacy Characteristics | ||

| Naloxone furnishing protocol | Yes | Yes |

| Government operated? | Yes | No |

| # of pharmacists | 2 | 1–4 |

| # of pharmacy technicians | 3 | 1–15 |

| # of naloxone units furnished per month | 89 | 1–15 |

| Prescription volume per day | 100 | 250–600 |

| # of patients with OUD diagnosis served | 99%* | Unknown |

Percentage only includes walk-in clients to the pharmacy and does not account for clients at affiliated clinics

Development and Implementation of Naloxone Furnishing Program

Through a structured thematic coding approach, 4 key areas for successful implementation of naloxone furnishing were identified. These were (a) corporate or administrative support, (b) pharmacist-led initiatives, (c) efforts to increase pharmacists’ furnishing of naloxone, and (d) efforts to increase patient engagement with naloxone furnishing. Each of the factors within these four key areas were inductively coded; examples drawn from participant interviews are provided in Table 2.

Table 2:

Implementation Strategy

| Corporate / Administrative Support | |

|---|---|

| CBHS Pharmacy | Chain Pharmacy |

|

|

| Pharmacist Led Efforts | |

|

|

| Increasing Pharmacist Engagement | |

|

|

| Increasing Patient Engagement | |

|

|

CBHS Pharmacy has strong administrative support that reflects efforts by the City and County of San Francisco to reduce opioid overdoses. This includes setting naloxone furnishing as a pharmacy goal and performance metric, and allocating funding for uninsured patients. In the words of one respondent, “We’ve always thought that Naloxone is very important. We’ve always put priority on that.” Corporate efforts by chain pharmacies have focused on improved automation, determining high risk patients based on the strength of an existing opioid prescription and applying available discounts using computerized patient records. As one respondent explained, “…the company pushed a protocol to have it for all patients flagged between the 50 and 90 or even more morphine equivalents.”

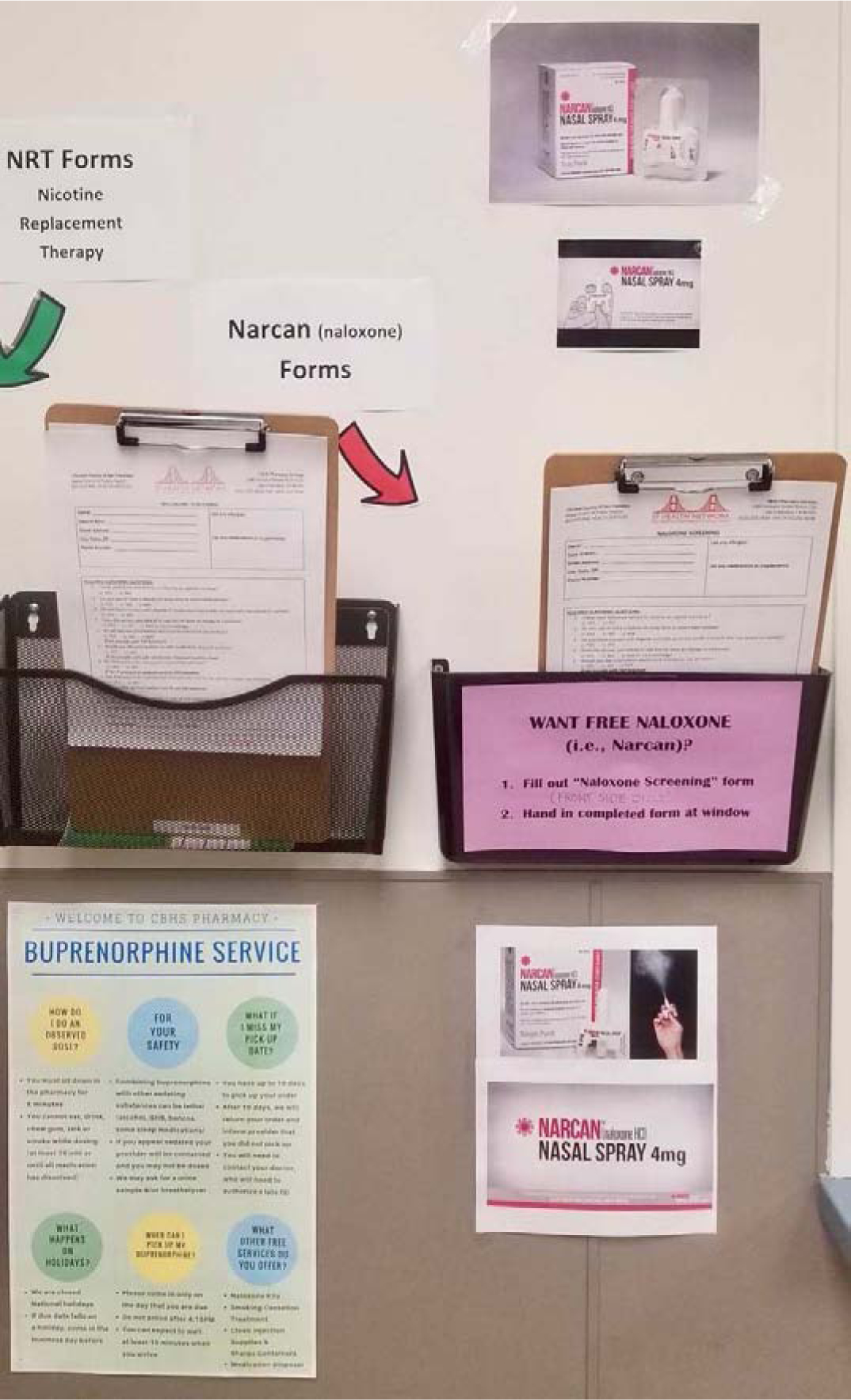

While there were substantial differences in specific approaches, both CBHS pharmacy and the three chain pharmacies identified pharmacists taking initiative was critical, as well preparing necessary documentation and resources. A CBHS pharmacist explained, “I think having like a champion, somebody that was willing to pilot it and write everything up and then spend time with staff to make sure they were comfortable doing it was helpful for us.” A chain pharmacist reported that, “It’s kind of on the store to reach out, get those resources and establish it.” In addition, both relied on free continuing professional education resources to train pharmacists in furnishing, and both had established organizational strategies such as creating naloxone binders and pre-filled forms (Figure 1). Both also indicated that it was necessary to create more awareness of pharmacists’ expanded role in providing care as a means of increasing community and healthcare engagement with naloxone furnishing. One chain pharmacist explained, “…sometimes if we’re on the phone with the prescriber [to] clarify something about an opioid… we’ll just say, ‘Hey, we noticed this patient’s not on naloxone. Can we just prescribe it in your behalf?’ A lot of times [they’re] like, Oh yeah, that’s a great idea.”

Figure 1:

Layout of CBHS pharmacy front waiting area illustrating naloxone furnishing information and screening form available to clients.

This engagement included reaching out to patients as well as providers. While CBHS approached this more aggressively (the CBHS Pharmacy Director estimated that “99% of the people that walk into our building” have opioid use disorders), chain pharmacies also sought to encourage opioid-using patients to accept naloxone. In the words of a CBHS pharmacist, “We recommend Naloxone to just about everybody. So we have signs in the waiting room [and] if you get any drugs, medications that are not from a pharmacy that are illicit, we recommend you have naloxone.” Chain pharmacies used an opt-out strategy: “When [the naloxone is] already all finished and done and it’s right in front of them and you’re counseling them, it’s better than trying to get their consent and then putting it in the works and having them come back later.”

Approaches Towards Addressing Barriers Identified in Past Research:

Previous studies have identified barriers that impede implementation of naloxone furnishing programs. These included lacking time to furnish naloxone, out-of-pocket cost to patients for obtaining naloxone, the perception that it would attract “unwanted clientele” who will increase theft or cause damage to the pharmacy or harm its staff, and stigma felt by patients who might seek to obtain naloxone (Table 3).11–17

Table 3:

Addressing Barriers

| Addressing Time Barrier | |

|---|---|

| CBHS Pharmacy | Chain Pharmacy |

|

|

| Addressing Cost Barrier | |

|

|

| Addressing Unwanted Clientele | |

|

|

| Addressing Stigma | |

|

|

Both CBHS Pharmacy and chain community pharmacies took similar approaches to the first two barriers. Time required to furnish was addressed by generating pre-filled naloxone prescriptions and having shorthand transcribing approaches which reduced processing time. A chain pharmacist explained “…we pre-print our Naloxone prescriptions, so it’s super easy, write the patient’s name and then your name and Narcan.” In addition, both types of pharmacies reported that Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid program) provided full coverage of naloxone, reducing out-of-pocket costs for lower-income patients. However CBHS pharmacy was also able to focus on lower-cost injectable medication given that “[our] population already knows how to use a needle.” Chain pharmacies, which serve patients covered under multiple forms of insurance, had a more complicated process. “I’m catching the patients that it will be free for, so all our Medi-Cal and fee-for-service or all our Medicare patients that have reached the deductible.”

Differences between CBHS and chain pharmacies arose in response to addressing perceptions of unwanted clientele and stigma felt by patients. While all study participants at CBHS pharmacy provided responses to address the question of unwanted clientele, only two of the three community pharmacies were willing to provide a response. The responses about “unwanted” clientele reflected different perceptions: CBHS employees indicated that they did not view any patient as unwanted” “I try to think of opioids as risky drugs, not the people that we’re giving them to as risky people.” In contrast, a chain pharmacist highlighted furnishing naloxone as a means to discourage unwanted clientele, because it slowed down prescription processing time, “…when you are slowing down the process in any way, those people normally don’t want to come back, because they want it quick. They want to basically bamboozle you into just dispensing their medication quickly.” Their approaches to reducing patient perceptions of stigma reflected this differences in perception about whether patients could be “unwanted.” CBHS staff emphasized their focus on being non-judgmental, “We want to be respectful, and also honor our clients, and we want to also see that they’re safe.” In contrast, chain pharmacists counseled in ways that attempted to convince patients that they were distinct from stigmatized patients, “…ultimately the best education and counseling points is not to use the word ‘overdose.’”

Discussion

There is little existing evidence evaluating strategies to implement pharmacy-based naloxone furnishing programs. As a result, our findings are exploratory. Through an inductive thematic approach, we identified implementation approaches and ways to circumvent pre-identified barriers to furnishing naloxone in community pharmacies. We found that while both the government-operated and chain community pharmacies identified similar ways to implement their programs, they took distinct approaches to addressing barriers, particularly with respect to the question of unwanted clientele. While previous studies on pharmacist-led naloxone furnishing have found low engagement and a range of barriers to naloxone furnishing, this study examined how to overcome and address these barriers.11–17 We found that the local government-operated and chain pharmacies used similar strategies, particularly in addressing furnishing time and cost to patients and identified new approaches such as providing educational materials while patients were waiting to reduce naloxone consultation time.

When comparing the two types of pharmacies, we found that the success of CBHS pharmacy in implementing its program was multifactorial, combining administrative priority and support, having a pharmacist champion spearheading implantation, advertising efforts, prepared documentation, and the staff’s sense of pride in treating the target population and perceptions that these services were critical and necessary. Replicating their comparatively high level of naloxone furnishing in other pharmacies would likely entail finding ways to change perceptions, specifically the belief in “risky drugs” rather than “risky people.”

For chain community pharmacies, we found that pharmacists reported similar factors leading to successful implementation but placed greater emphasis on time and efficiency, using strategies ranging from computer system improvements to pre-prepared prescriptions to make the additional workload manageable. All three chain pharmacies surveyed (CVS, Safeway, Walgreens) had a naloxone furnishing protocol and pharmacist training in place at the corporate level. However previous research has found that less than a quarter of California pharmacy locations have implemented such protocols.10 Implementation strategies across the different chain pharmacies varied widely. The successful pharmacies included in this study took advantage of their larger workforces to overcome the added time and barriers to furnishing naloxone, developed screening questions to identify at-risk patients, and had naloxone billed and ready before the patient requested it. They also used analogies during consultation to improve patient understanding of naloxone’s value and reduce perceptions that accepting naloxone prescriptions would stigmatize them.

The distinction between CBHS pharmacy and chain community pharmacies was highlighted by their approach to perceptions that furnishing would draw unwanted clientele and strategies to reduce perceptions of stigma felt by patients. “Unwanted clientele” in prior studies were defined as those that pharmacists assumed would cause theft, damage or harm to the pharmacy or staff.11–17 Not every respondent from chain pharmacies was willing to answer these questions. While this may stem from administrative pressure or hesitation in sharing personal beliefs, this avoidance highlights hesitancy as a potential limitation in expansion of naloxone furnishing. Further investigation is needed to explore the driver of this non-response. Those respondents from chain pharmacies that did answer the question indicated that they resolved concern about unwanted clientele by attempting to create unfavorable situations for clients that they preferred not to treat. CBHS pharmacy took a different approach by welcoming all clients, which respondents indicated stemmed from their public health focus.

Limitations

This study focused on the four community pharmacies in San Francisco that actively furnished naloxone. Research in other localities may provide additional insight into undetected cultural and legal influences. This study also excluded pharmacies that did not furnish naloxone; including such sites in future research may provide additional perspective. While our interview guide was designed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of naloxone furnishing, by its nature, interviews are subject to self-reporting biases. Potential administrative pressure to provide positive response may have led to exaggeration or telescoping, personal commitment to the program may have generated overly positive outlooks, and there may have been cultural bias in interpreting or explaining events. Due to limited geographical scope, small sample size, and purposive sampling of pharmacies, the generalizability of this study may be limited. As an exploratory study, these findings nonetheless shed light into the furnishing practices that could be applicable in many community pharmacy settings.

Conclusions:

The increase in opioid overdoses have affected the lives of many Americans. As part of the efforts to address this problem, pharmacists in California and other states have been empowered to furnish naloxone in an effort to reduce opioid overdoses. However uptake of naloxone furnishing by California pharmacies has been slow,10 and research to date has focused on barriers, with little evidence showing how pharmacies interested in furnishing naloxone can proceed. To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate strategies used to implement naloxone furnishing programs within community pharmacy practice settings.25 While each pharmacy in our study identified factors unique to their location, their approaches had common features that were not limited to any specific pharmacy, and many of the strategies identified were replicable. A persistent barrier, however, is providing access to vulnerable groups at high risk of overdose, a population that some respondents from chain community pharmacies have indicated that they are not currently willing to serve.11–17 Our findings provide guidelines that community pharmacies can use to engage patients and expand naloxone access, and by doing so, help reduce opioid overdoses.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

What was already known:

Naloxone can reverse the effects of opioid overdoses, which have risen sharply in the US

Multiple states have expanded the role of pharmacists by allowing them to furnish naloxone to the public

Participation and Implementation of naloxone furnishing practices in community pharmacies has been limited, and research reports multiple barriers

What this study adds:

This study examines successful naloxone furnishing practices of 4 community pharmacies, rather than barriers to furnishing

We examined both major chain community pharmacies and a community public health pharmacy to identified key factors contributing to successful implementation of naloxone furnishing

We identified common factors for success in both implementation and overcoming known barriers, many of which could be used design and implement naloxone furnishing programs in other community pharmacies

Funding:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [DA046051] (Apollonio) and a UCSF School of Pharmacy Pathway Grant (Nguyen). The funders played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests: The authors have no actual or potential competing financial interests to report.

Previous Presentations of Findings: California Society of Health Systems Pharmacist Seminar 2019 (poster); Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Midyear Conference 2019 (poster)

References

- 1.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose Deaths | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center. Opioid Overdose 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- 2.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;67(5152):1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boom M, Niesters M, Sarton E, Aarts L, Smith TW, Dahan A. Non-analgesic effects of opioids: opioid-induced respiratory depression. Current pharmaceutical design. 2012;18(37):5994–6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Opioid Overdose Reversal with Naloxone (Narcan, Evzio) | National Institute on Drug Abuse. Opioids 2020; https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/opioids/opioid-overdose-reversal-naloxone-narcan-evzio. Accessed July 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sporer KA. Acute heroin overdose. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(7):584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enteen L, Bauer J, McLean R, et al. Overdose prevention and naloxone prescription for opioid users in San Francisco. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2010;87(6):931–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer M, Baer HA, Scott G, Horowitz S, Weinstein B. Pharmacy access to syringes among injecting drug users: follow-up findings from Hartford, Connecticut. Public health reports (Washington, DC: 1974). 1998;113 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):81–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bill Text - AB-1535 Pharmacists: naloxone hydrochloride. Bloom, trans. 2013–2014. ed2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puzantian T, Gasper JJ. Provision of Naloxone Without a Prescription by California Pharmacists 2 Years After Legislation Implementation. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1933–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green TC, Case P, Fiske H, et al. Perpetuating stigma or reducing risk? Perspectives from naloxone consumers and pharmacists on pharmacy-based naloxone in 2 states. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association: JAPhA. 2017;57(2s):S19–S27.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman PR, Goodin A, Troske S, Strahl A, Fallin A, Green TC. Pharmacists’ role in opioid overdose: Kentucky pharmacists’ willingness to participate in naloxone dispensing. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association: JAPhA. 2017;57(2s):S28–s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson EL, Rao PSS, Hayes C, Purtill C. Dispensing Naloxone Without a Prescription: Survey Evaluation of Ohio Pharmacists. Journal of pharmacy practice. 2019;32(4):412–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaller ND, Yokell MA, Green TC, Gaggin J, Case P. The Feasibility of Pharmacy-Based Naloxone Distribution Interventions: A Qualitative Study With Injection Drug Users and Pharmacy Staff in Rhode Island. Substance use & misuse. 2013;48(8):590–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haug NA, Bielenberg J, Linder SH, Lembke A. Assessment of provider attitudes toward #naloxone on Twitter. Substance Abuse. 2016;37(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur T, Frey M, Chewning B. Pharmacist roles, training, and perceived barriers in naloxone dispensing: A systematic review. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association: JAPhA.2020;60(1):178–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakhireva LN, Bautista A, Cano S, Shrestha S, Bachyrycz AM, Cruz TH. Barriers and facilitators to dispensing of intranasal naloxone by pharmacists. Subst Abus. 2018;39(3):331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green TC, Dauria EF, Bratberg J, Davis CS, Walley AY. Orienting patients to greater opioid safety: models of community pharmacy-based naloxone. Harm reduction journal. 2015;12:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volkow N An on Drug Ambitious Research Plan to Help Solve the Opioid Crisis | National Institute Abuse. Nora’s Blog 2018; https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/norasblog/2018/06/ambitious-research-plan-to-help-solve-opioid-crisis. Accessed July 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patton SJ, Miller FA, Abrahamyan L, Rac VE. Expanding the clinical role of community pharmacy: A qualitative ethnographic study of medication reviews in Ontario, Canada. Health policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2018;122(3):256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80. Medical Teacher. 2013;35(8):e1365–e1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Substance Use Research Unit. Recent Surge in Opioid Overdose Events in San Francisco. In: Health PHDSFDoP, ed. San Francisco, CA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golafshani N Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report. 2003;8:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali A, Yusof H. Quality in Qualitative Studies: The Case of Validity, Reliability and Generalizability. Issues In Social And Environmental Accounting. 2011;5:25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saldaña J The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Washington, DC: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.