Abstract

Background:

Lead (Pb) is an environmental factor has been suspected of contributing to the dementia including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Our previous studies have shown that Pb exposure at the subtoxic dose increased brain levels of beta-amyloid (Aβ) and amyloid plaques, a pathological hallmark for AD, in amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice, and is hypothesized to inhibit Aβ clearance in the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier. However, it remains unclear how different levels of Pb affect Aβ clearance in the whole blood-brain barrier system. This study was designed to investigate whether chronic exposure of Pb affected the permeability of the blood-brain barrier system by using the Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Computerized Tomography (DCE-CT) method.

Methods:

DEC-CT was used to investigate whether chronic exposure of toxic Pb affected the permeability of the real-time blood brain barrier system.

Results:

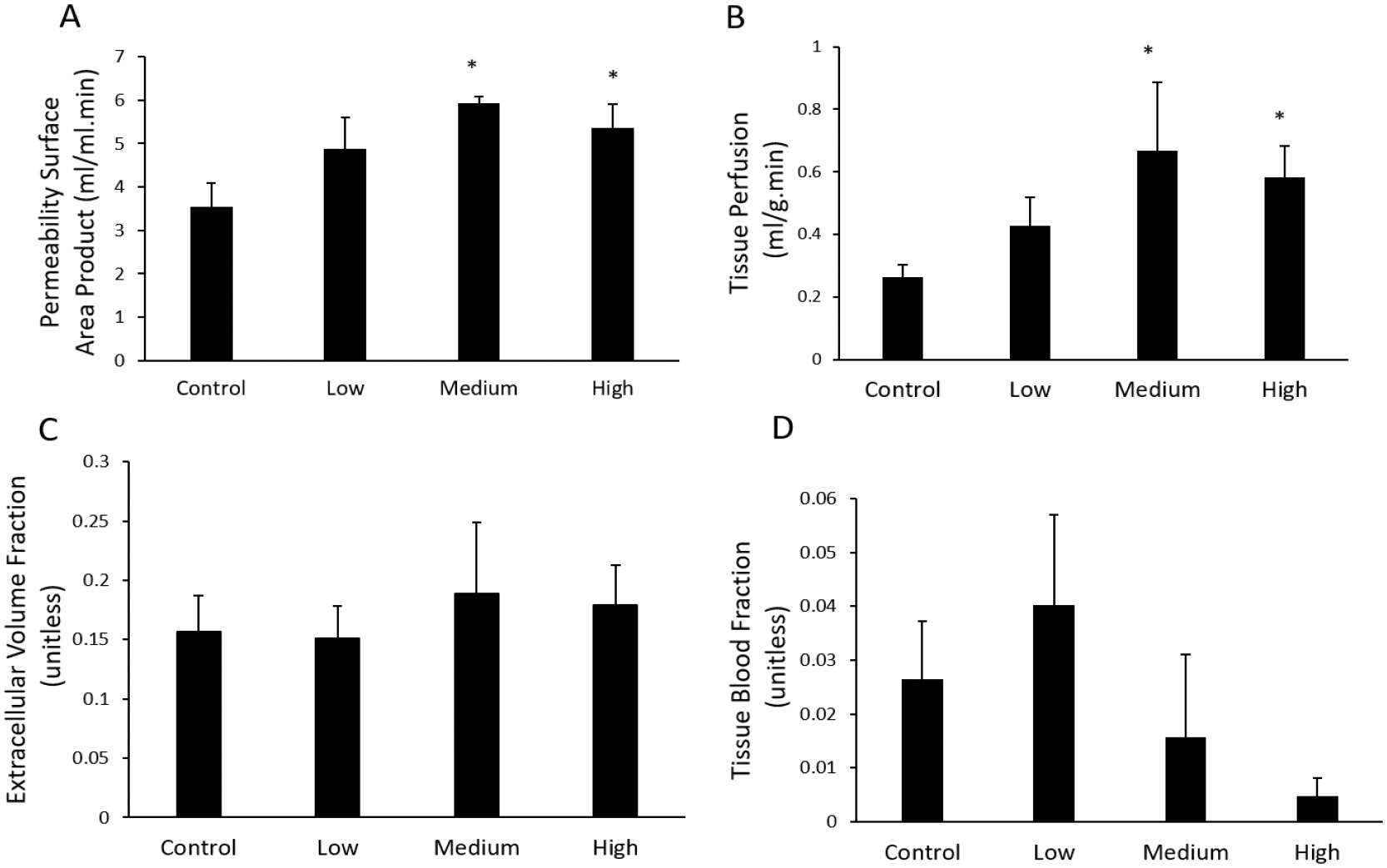

Data showed that Pb exposure increased permeability surface area product, and also significantly induced brain perfusion. However, Pb exposure did not alter extracellular volumes or fractional blood volumes of mouse brain.

Conclusion:

Our data suggest that Pb exposure at subtoxic and toxic levels directly targets the brain vasculature and damages the blood brain barrier system.

Keywords: Lead, Alzheimer’s disease, beta amyloid, DCE-CT, permeability, APP transgenic mice

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the most common causes of dementia over the age of 65 years [1]. Aggregation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) in the brain extracellular space to form the insoluble plaques is a hallmark of AD [2], and aggregated Aβ can further stimulate hyperphosphorylation of tau leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles in nerve terminals [3]. In AD patients, Aβ is also found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulating in brain ventricles, and in the interstitial fluid around neurons and glial cells [4–7]. We and others have shown the role of the blood brain barrier system in regulating brain Aβ homeostasis [8–11]. The blood brain barrier system includes two types of barriers that separate the blood circulation from brain functional structures, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) between blood and interstitial fluid as well as the blood-CSF barrier between blood and CSF. BBB leakage due to microvascular injury, thinning and discontinuities in the AD has been reported in literature [12]. In AD, disrupted BBB may cause the dysfunction of Aβ transport from brain to the peripheral circulation [13]. Additionally, choroid plexus may also be involved in AD etiology [14–16]. Studies have found that choroid plexus participates in brain amyloidosis and Aβ transport [14, 15, 17, 18]. Brain autopsies of AD patients reveal an extensive accumulation of Aβ plaques in the choroid plexus [19, 20].

Lead (Pb) is an environmental factor has been implicated in the development of AD and related dementias [21–24]. Since the blood brain barrier system is the identified target of Pb toxicity [25], it is quite possible that Pb toxicity may affect the critical processes in the blood brain barrier system that regulate Aβ transport and metabolism. Our previous studies have shown that Pb exposure at the subtoxic dose significantly increased brain levels of Aβ and amyloid plaques in an amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mouse model, Tg-SwDI mice, a mouse model widely used to study AD and amyloid pathogenesis [26, 27], possibly by inhibiting Aβ clearance in the blood-CSF barrier [22, 28]. Despite these findings, it remains unclear how different levels of Pb affect Aβ transport in the whole blood-brain barrier system.

Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Computerized Tomography (DCE-CT) is a medical imaging technology that utilizes trace quantity of a contrast agent and the Stewart-Hamilton indicator dilution approach [29] to mathematically determine tracer dynamics. Typically, an iodinated based tracer in injected into the subjects venous circulation, and serial 3D images at regular intervals are acquired, thus permitting mathematical modeling of cerebral blood volume and microvascular permeability changes in both animal and human brains [30, 31]. Moreover, this technique has been adapted for animal models to quantify cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume in brain tumor studies [32–35], where the DCE-CT contrast agent Isovue-370 was employed because of its high molecular weight, lack of cell permeation, and diffusion limitation across the vascular wall. These physiochemical properties, combined with the kinetic modeling permits the estimate of permeability surface area product, delineation of cerebrovascular vessels, and underlying neural tissues, thus providing the dynamic information of blood supply in relation to the supporting tissue [33, 35, 36]. This technique has thus been widely used to evaluate permeability surface area product as a measure of blood brain barrier permeability in animal models [37–40]. Importantly, this approach can be applied in research and clinical studies for AD, since it can detect the real-time blood brain barrier system permeability induced by extrinsic factors such as Pb. The current study seeks to investigate whether chronic exposure of toxic Pb affected the permeability of the real-time blood brain barrier system by using the above mentioned DCE-CT approach.

2. Materials and Methods

Tg-SwDI mice [Jackson Laboratory, 22] were housed 3–5 per cage, fed ad libitum rodent chow (Envigo Teklad) and had free access to water. In all cases, mice were maintained in a 12-h light/dark cycle, where the room was maintained at 23±2 °C (40% relative humidity). Tg-SwDI mice at the time of experimentation were 8 weeks old and were randomly allocated to one of four groups. The experimental dosing regime was originally designed as four-week treatments. However, since Pb at the highest dose caused significant toxicity, mice in the high dose group were administered with 100 mg/kg Pb-acetate (equivalent to Pb at 54 mg/kg) by oral gavage once daily for 1 week. In contrast, mice in the low or medium dose groups were orally treated with 25 or 50 mg/kg Pb-acetate (equivalent to Pb at 13.5 or 27 mg/kg) for 4 weeks. As a control group, mice were treated with Na-acetate (21mg/kg, an equivalent molar concentration of Pb-acetate at 100 mg/kg) since our studies showed there were no effects of Na-acetate at 21 mg/kg or less either on amyloid deposition or DEC-CT data. This dose regimen has been shown to produce a significant accumulation of Pb in mice brain, and is similar to those levels found in children [28]. All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.2 prior to the oral gavage. Pb levels in brain tissues were quantified by a Varian SpectroAA-20 Plus GTA-96 flameless graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrophotometry analysis [22].

A clinical computerized tomography (CT) scanner (Philips Brilliance 128 iCT) was used to acquire data at 120×1sec, 50×2sec, and 10×10sec images using the following CT technique 80kVp; 80mAs and 0.625 mm slice thickness. Scans were acquired using helical scanning with a 0mm step size. Image volumes and were reconstructed using filtered back-projection with a 70% Hamming cutoff filter, yielding 0.3×0.3×0.625 mm2 voxel sizes, the approximate resolution of the scanner. Prior to imaging, each mouse was induced with 5% isoflurane and maintained at1–1.5% isofluorane. The animal was positioned within the CT scanner, such that the field of view contained both the heart and brain. The scanner was initiated, and at the 5th frame (i.e. 5sec), each subject was infused with 0.2ml of Isovue-370 (Bracco Diagnostics) at 3ml/min via remote infusion pump (PHD2000, Harvard Medical), followed by a saline flush to ensure complete contrast administration. Image volumes were continuously acquired without pausing. Reconstructed and calibrated CT images were imported into Analyze 12 (AnalyzeDirect, Stillwell KS) and all image volumes were registered to the first volume using a normalized entropy mutual information algorithm [41]. Using the image volume with peak contrast, images were segmented using a semi-automated thresholding technique to extract the whole brain volumes (Figure 1). To permit collection of the arterial input function, the left ventricle was manually segmented, taking care not to include the septum or free wall of the myocardium. Post segmentation, time courses for both brain and AIF were extracted using ROITool (AnalyzeDirect, Stillwell KS) and stored for subsequent modeling.

Figure 1.

Representative CT images of the mouse brain and DEC-CT operational model diagram. (A) representative 3D rendering of a mouse brain and approximate slice location shown in panels B-D (black plane). (B) CT image prior to DCE injection, (C) CT image at peak contrast concentration, (D) region mask of mouse brain. (E) DCE-CT Operational Model Diagram. It describes the compartments and rate constants which describe the mass balance of IsoVue 370, which is a cell impermeant diffusion limited CT contrast agent. IsoVue 370 (blue ellipse) introduced into the central blood compartment via tail vein (red ellipse) which distributes to the brain compartment (orange ellipse) and back to the central compartment based on the permeability surface area product.

In order to extract relevant physiological parameters from the transit of the iodinated radio-opaque contrast agent, the following coupled linear differential tracer kinetic model equations (Figure 1) were applied:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Where, i, t, Cp, Cb, CT, PS, ve, F, E, ρ, and Fbv are the subject, time, concentration of the tracer in the plasma, brain interstitial spaces, and total tracer concentration, permeability surface area product (ml/ml.min), volume of the extra vascular spaces (unitless), blood flow (ml/g.min), tissue extraction (unitless), tissue density (g/ml), and fractional volume of the blood vessels within each voxel (unitless), as previously described [42]. In all cases, model parameters were estimated via eNumerate (developed by Paul R. Territo) with the following characteristics: Levenberg-Marquardt parameter optimizer, trapezoidal-quadrature, uniform weighting, hematocrit of 0.42 [42], and a relative sum-of-squares convergence of 1e-12.

In all cases, statistical analysis was performed to compare data obtained from the Pb-treated group and the Na-treated control group using two tailed Student t-test with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons, where significance was taken at the p<0.05 level.

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of a clinically translatable imaging method, DCECT, which allows noninvasive monitoring and quantifying the real-time cerebral regional blood flow, blood volume, and the blood brain barrier system permeability simultaneously. Fitting of the individual time courses to the operational model described by Figure 1 and Eqns. 1–4 showed a high degree of fit with an average R2 of 0.832 ± 0.026 (N = 44). Analysis of residual error (i.e. observed – model), showed minimal under/over fitting across time and treatment. Similarly, residual error analysis (i.e. frequency of residual errors) for all treatment groups were normally distributed, with an mean of −1.2 (range −0.6 to −1.8) Hounsfield units (HU), and full-width at half-max distribution of ± 3.5 HU units of error, indicating that the model was appropriate to describe the individual time courses with minimal modeling bias. Quantitative surface area product is an imaging marker of the blood brain barrier system permeability [37].

After 2-week treatments, more than 20% of mice treated with 100 mg/kg died and 60% lost more than 20% of their initial weight. Thus, Tg-SwDI mice administrated with the high dose of Pb-acetate for only 1 week were analyzed in the DET-CT study. Additionally, Tg-SwDI mice treated with medium and low doses of Pb-acetate for four weeks did not significantly lose weight and were directly analyzed by DET-CT. The Pb level in control mice brain is 0.05 ± 0.02 ug/g (n=9). 7-day exposure of Pb at 54 mg/kg produced a significant accumulation of 1.11 ± 0.10 ug/g Pb in mice brain (n=4). 4-week exposure of 27 mg/kg and 13.5 mg/kg Pb increased Pb levels to 0.49 ± 0.05 μg/g (n=9) and 0.28 ± 0.09 ug/g (n=8) in mice brain.

We have found that both 7-day exposure of Pb at 54 mg/kg and 4-week chronic exposure at 27 mg/kg significantly induced the permeability of the blood brain barrier system in Tg-SwDI mice (Figure 2A), suggesting that chronic Pb exposure at toxic and subtoxic levels may directly injury the brain barrier system. Similar data were also observed in the 4-week imaging study, where very low dosage of Pb exposure at 13.5 mg/kg also had a similar trend. It appeared detrimental effects of chronic Pb at different doses on the blood brain barrier system were similar. Analysis of whole brain perfusion revealed that the medium and high Pb exposures resulted in significantly elevated tissue perfusion (Figure 2B), consistent with Pb disruption of the vascular integrity and a net loss of vasomotor tone [43]. Quantitative analysis of brain extracellular volume did not show a dose dependent change with exposure to Pb (Figure 2C), consistent with notion that the endothelial of the brain vasculature was not accompanied by loss of extracellular space [44, 45]. Similarly, estimates of fractional blood volumes, which describe the fraction of the signal in a given voxel (or region) which are occupied by blood, did show a trend towards decreasing with Pb dose (Figure 2D); however these changes were not statistically significant at the p<0.05 level. Our data suggest the blood brain barrier system is one of the vulnerable areas to Pb toxicity and even ‘current safe’ dosages of Pb (a reference children blood Pb level of 5 μg/dL in 2012) [46] could quickly disrupt their function that may together with other risk factors result in neuronal injury disorders including dementia by allowing blood contents to escape into the brain parenchyma via disrupted the blood brain barrier system [47]

Figure 2.

Tracer kinetic model analysis of permeability surface area product, brain tissue perfusion, extra cellular volume, and fractional blood volume. N=8 (Control, Na-acetate, four weeks), 9 (low dose, four weeks), 8 (medium dose, four weeks), and 4 (high dose, one week). Statistical analysis was conducted to compare data obtained from the Pb-treated group at each dose and the Na-treated control group. Significance was taken at the p<0.05 (*). Data were presented at Mean±SEM.

Chronic Pb exposure has been shown to cause the structural damage in rats. In our previous study, Pb exposure in young rats induces an extensive extravascular staining of lanthanum nitrate, a known marker for BBB leakage, in brain parenchyma by the electron microscope, suggesting a leakage of cerebral vasculature [48]. Evidence in literature also demonstrates that Pb may directly damage the barrier structure so as to increase the permeability of the BBB; the endothelial bud appears to be particularly sensitive to Pb toxicity, resulting in Pb-induced death of these buds [49–51]. On the other hand, many studies have also suggested that BBB breakdown is involved in AD development [47]. Our current in vivo study by real-time imaging analysis provides the direct strong evidence that chronic low-dose Pb exposure can damage the blood brain barrier system in transgenic AD APP mice, which may contribute to the etiology of AD.

Interestingly, we also found chronic Pb treatments induced brain perfusion in a similar way to the induction of brain barrier system permeability. Although cerebral hypoperfusion has been proposed to promote AD development and amyloid deposition [47, 52], high Aβ load has also been found to be associated with longitudinal hyperperfusion in certain brain areas [53]. Hyperperfusion found in certain brain areas including hippocampus of mild AD patients suggests possible compensatory effects from inflammation or other vasodilatory stimulus [54, 55]. Since inflammation may play a role in inducing both brain permeability and perfusion [56], it will be interesting to investigate whether inflammation plays a role in chronic Pb-induced the permeability of the blood brain barrier and brain perfusion in Tg-SwDI mice.

The current study has the following limitations. First, we did not directly use Aβ as a trace marker. While the increased BBB permeability may presumably increase the leakage of blood-borne Aβ into the brain, the conclusion on Pb interaction with Aβ transport would become much stronger if the assay is done. A pertinent study is currently in progress. Second, DEC-CT offers the technical advantage in assessing the integrity of the blood brain barrier system; yet the question as to how Pb exposure specifically impairs the BBB or blood-CSF barrier cannot be addressed by current DEC-CT. Finally, mathematical models used in DEC-CT need to be further evaluated for their pathophysiological relevance.

6. Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIEHS R01 ES027078 to W.Z and Y.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Hebert LE, et al. , Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology, 2013. 80(19): p. 1778–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ogomori K, et al. , Beta-protein amyloid is widely distributed in the central nervous system of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol, 1989. 134(2): p. 243–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hernandez F, et al. , GSK3: a possible link between beta amyloid peptide and tau protein. Exp Neurol, 2010. 223(2): p. 322–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Price DL, Sisodia SS, and Borchelt DR, Genetic neurodegenerative diseases: the human illness and transgenic models. Science, 1998. 282(5391): p. 1079–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Selkoe DJ, Biochemistry of altered brain proteins in Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci, 1989. 12: p. 463–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Seubert P, et al. , Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer’s beta-peptide from biological fluids. Nature, 1992. 359(6393): p. 325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vigo-Pelfrey C, et al. , Characterization of beta-amyloid peptide from human cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurochem, 1993. 61(5): p. 1965–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Crossgrove JS, Li GJ, and Zheng W, The choroid plexus removes beta-amyloid from brain cerebrospinal fluid. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2005. 230(10): p. 771–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Crossgrove JS, Smith EL, and Zheng W, Macromolecules involved in production and metabolism of beta-amyloid at the brain barriers. Brain Res, 2007. 1138: p. 187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zlokovic BV, Clearing amyloid through the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem, 2004. 89(4): p. 807–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Behl M, Zhang Y, and Zheng W, Involvement of insulin-degrading enzyme in the clearance of beta-amyloid at the blood-CSF barrier: Consequences of lead exposure. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res, 2009. 6: p. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zipser BD, et al. , Microvascular injury and blood-brain barrier leakage in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging, 2007. 28(7): p. 977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cai Z, et al. , Role of Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 2018. 63(4): p. 1223–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Serot JM, et al. , Choroid plexus and ageing in rats: a morphometric and ultrastructural study. Eur J Neurosci, 2001. 14(5): p. 794–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kalaria RN, et al. , Production and increased detection of amyloid beta protein and amyloidogenic fragments in brain microvessels, meningeal vessels and choroid plexus in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 1996. 35(1–2): p. 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Alvira-Botero X, et al. , Megalin interacts with APP and the intracellular adapter protein FE65 in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2010. 45(3): p. 306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Monro OR, et al. , Substitution at codon 22 reduces clearance of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptide from the cerebrospinal fluid and prevents its transport from the central nervous system into blood. Neurobiol Aging, 2002. 23(3): p. 405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sasaki A, et al. , Human choroid plexus is an uniquely involved area of the brain in amyloidosis: a histochemical, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Brain Res, 1997. 755(2): p. 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Miklossy J, et al. , Alzheimer disease: curly fibers and tangles in organs other than brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 1999. 58(8): p. 803–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Eriksson L and Westermark P, Characterization of Intracellular Amyloid Fibrils in the Human Choroid-Plexus Epithelial-Cells. Acta Neuropathologica, 1990. 80(6): p. 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jiang YM, et al. , Evidence for altered hippocampal volume and brain metabolites in workers occupationally exposed to lead: a study by magnetic resonance imaging and (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Toxicol Lett, 2008. 181(2): p. 118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gu H, et al. , Increased beta-amyloid deposition in Tg-SWDI transgenic mouse brain following in vivo lead exposure. Toxicol Lett, 2012. 213(2): p. 211–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bihaqi SW and Zawia NH, Enhanced taupathy and AD-like pathology in aged primate brains decades after infantile exposure to lead (Pb). Neurotoxicology, 2013. 39: p. 95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bihaqi SW, et al. , Infantile exposure to lead and late-age cognitive decline: relevance to AD. Alzheimers Dement, 2014. 10(2): p. 187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zheng W, Aschner M, and Ghersi-Egea JF, Brain barrier systems: a new frontier in metal neurotoxicological research. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2003. 192(1): p. 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Petrushina I, et al. , Characterization and preclinical evaluation of the cGMP grade DNA based vaccine, AV-1959D to enter the first-in-human clinical trials. Neurobiol Dis, 2020. 139: p. 104823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Davis J, et al. , Early-onset and robust cerebral microvascular accumulation of amyloid beta-protein in transgenic mice expressing low levels of a vasculotropic Dutch/Iowa mutant form of amyloid beta-protein precursor. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(19): p. 20296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gu H, et al. , Lead exposure increases levels of beta-amyloid in the brain and CSF and inhibits LRP1 expression in APP transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett, 2011. 490(1): p. 16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stewart GN, Researches on the Circulation Time and on the Influences which affect it. J Physiol, 1897. 22(3): p. 159–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Roberts HC, et al. , Dynamic, contrast-enhanced CT of human brain tumors: quantitative assessment of blood volume, blood flow, and microvascular permeability: report of two cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2002. 23(5): p. 828–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schwickert HC, et al. , Contrast-enhanced MR imaging assessment of tumor capillary permeability: effect of irradiation on delivery of chemotherapy. Radiology, 1996. 198(3): p. 893–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cenic A, et al. , A CT method to measure hemodynamics in brain tumors: validation and application of cerebral blood flow maps. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2000. 21(3): p. 462–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cao M, et al. , Developing DCE-CT to quantify intra-tumor heterogeneity in breast tumors with differing angiogenic phenotype. IEEE Trans Med Imaging, 2009. 28(6): p. 861–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Krishnamurthi G, et al. , Functional imaging in small animals using X-ray computed tomography--study of physiologic measurement reproducibility. IEEE Trans Med Imaging, 2005. 24(7): p. 832–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Stantz KM, et al. , Monitoring the longitudinal intra-tumor physiological impulse response to VEGFR2 blockade in breast tumors using DCE-CT. Mol Imaging Biol, 2011. 13(6): p. 1183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kovar DA, Lewis M, and Karczmar GS, A new method for imaging perfusion and contrast extraction fraction: input functions derived from reference tissues. J Magn Reson Imaging, 1998. 8(5): p. 1126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weidman EK, et al. , Evaluating Permeability Surface-Area Product as a Measure of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability in a Murine Model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2016. 37(7): p. 1267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Avsenik J, Bisdas S, and Popovic KS, Blood-brain barrier permeability imaging using perfusion computed tomography. Radiol Oncol, 2015. 49(2): p. 107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cuenod CA and Balvay D, Perfusion and vascular permeability: basic concepts and measurement in DCE-CT and DCE-MRI. Diagn Interv Imaging, 2013. 94(12): p. 1187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Thrippleton MJ, et al. , Quantifying blood-brain barrier leakage in small vessel disease: Review and consensus recommendations. Alzheimers Dement, 2019. 15(6): p. 840–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hanson KM, et al. , Normalized entropy measure for multimodality image alignment. 1998. 3338: p. 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tofts PS, et al. , Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging, 1999. 10(3): p. 223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Younes ST and Ryan MJ, Pathophysiology of Cerebral Vascular Dysfunction in Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2019. 21(7): p. 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lo WD, et al. , Blood-brain barrier permeability and the brain extracellular space in acute cerebral inflammation. J Neurol Sci, 1993. 118(2): p. 188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ivanidze J, et al. , Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Correlation With Clinical Outcomes. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2018. 211(4): p. 891–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Betts KS, CDC updates guidelines for children’s lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect, 2012. 120(7): p. a268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kisler K, et al. , Cerebral blood flow regulation and neurovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2017. 18(7): p. 419–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wang Q, et al. , Iron supplement prevents lead-induced disruption of the blood-brain barrier during rat development. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2007. 219(1): p. 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bradbury MW and Deane R, Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to lead. Neurotoxicology, 1993. 14(2–3): p. 131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Press MF, Lead-induced permeability changes in immature vessels of the developing cerebellar microcirculation. Acta Neuropathol, 1985. 67(1–2): p. 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Struzynska L, et al. , Lead-induced abnormalities in blood-brain barrier permeability in experimental chronic toxicity. Mol Chem Neuropathol, 1997. 31(3): p. 207–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Daulatzai MA, Cerebral hypoperfusion and glucose hypometabolism: Key pathophysiological modulators promote neurodegeneration, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res, 2017. 95(4): p. 943–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sojkova J, et al. , Longitudinal cerebral blood flow and amyloid deposition: an emerging pattern? J Nucl Med, 2008. 49(9): p. 1465–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dai W, et al. , Mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer disease: patterns of altered cerebral blood flow at MR imaging. Radiology, 2009. 250(3): p. 856–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Alsop DC, et al. , Hippocampal hyperperfusion in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage, 2008. 42(4): p. 1267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ingrisch M, et al. , Quantification of perfusion and permeability in multiple sclerosis: dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in 3D at 3T. Invest Radiol, 2012. 47(4): p. 252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]