Abstract

Opioid abuse is a major health problem. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the potentially disruptive side effects and therapeutic potential of a novel antagonist (D24M) of the mu-/delta-opioid receptor (MOR/DOR) heterodimer in male rats. Administration of high doses of D24M (1 & 10 nmol) into the lateral ventricle did not disrupt home cage wheel running. Repeated twice daily administration of increasing doses of morphine (5 to 20 mg/kg) over 5 days depressed wheel running and induced antinociceptive tolerance measured with the hot plate test. Administration of D24M had no effect on morphine tolerance, but tended to prolong morphine antinociception in non-tolerant rats. Spontaneous morphine withdrawal was evident as a decrease in body weight, a reduction in wheel running and an increase in sleep during the normally active dark phase of the circadian cycle, and an increase in wheel running and wakefulness in the normally inactive light phase. Administration of D24M during the dark phase on the third day of withdrawal had no effect on wheel running. These data provide additional evidence for the clinical relevance of home cage wheel running as a method to assess spontaneous opioid withdrawal in rats. These data also demonstrate that blocking the MOR/DOR heterodimer does not produce disruptive side effects or block the antinociceptive effects of morphine. Although administration of D24M had no effect on morphine withdrawal, additional studies are needed to evaluate withdrawal to continuous morphine administration and other opioids in rats with persistent pain.

Keywords: MOR/DOR Heterodimer, Antinociception, Morphine tolerance, Opioid withdrawal, Wheel running

1. Introduction

Opioid abuse is a major health problem affecting millions of Americans and causing over 42,000 overdose deaths in 2016 [1]. Animal research can help solve this problem by identifying drugs that produce antinociception in the absence of dependence, block the development of opioid tolerance, or reduce the symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Unfortunately, despite a few minor advances, drug development using animal models has failed on all three counts. A major problem with many previous studies is that drugs are evaluated by their ability to inhibit pain-evoked and withdrawal behaviors. Many drugs (e.g., anesthetics, paralytics) fail to translate to human use because of non-specific inhibition of behavior or unwanted side effects. The present study uses a clinically relevant approach (measurement of changes in activity; intermittent administration of morphine; assessment of spontaneous opioid withdrawal) to determine the function of the mu-/delta opioid receptor (MOR/DOR) heterodimer by injecting a novel and specific antagonist into rats made dependent on morphine.

Morphine antinociception and dependence is mediated by mu-opioid receptors (MOR). MOR signaling appears to be regulated by the delta-opioid receptor (DOR) possibly by the formation of MOR/DOR heterodimers[2–5]. MOR/DOR signaling has been reported to both attenuate [6] and produce[7,8] antinociception. The recent development and testing of a MOR/DOR antagonist (D24M) [9] could be used to resolve this conflict. Moreover, this antagonist could provide a novel treatment for opioid tolerance and dependence. Intracerebroventricular (icv) administration of D24M in mice blocked the antinociceptive effect of a MOR/DOR agonist and attenuated naloxone-precipitated withdrawal symptoms in morphine dependent mice [9]. The present study extends this work by examining the ability of D24M to modulate morphine tolerance and withdrawal following icv administration in rats.

The overall goal of treatments for pain or withdrawal is to restore normal function by reducing symptoms in the absence of unwanted side effects. With this goal in mind, the present study tests the effect of the MOR/DOR antagonist, D24M, using both traditional (i.e., hot plate test) and innovative (home cage wheel running) tests to gain a better understanding of potential effects on antinociception, tolerance, and withdrawal. Wheel running is depressed by pain [10,11], the side effects of drugs (e.g., morphine THC) [12,13], and opioid withdrawal [14]. Home cage wheel running provides a continuous measure of animal well-being and will be used to answer two questions: 1) Does D24M produce side effects that disrupt normal behavior? And 2) Does administration of D24M restore activity depressed by morphine withdrawal?

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

A total of 62 male Sprague-Dawley rats with a mean weight of 296 g (range of 260 – 396 g; 60 – 90 days old) were used. All rats were housed in pairs until a week before the experiment started at which time each rat was housed individually with a cage containing a running wheel (33 cm diameter Tecniplast Rat Running Wheel, Starr Life Sciences Corp., Oakmont, PA). Rats were tested in groups of eight in an isolated room on a 12:12 hr light cycle (Lights off at 10:30 AM). Animal care occurred during the hour before the beginning of the dark phase. At no other time were the rats disturbed except to administer injections (see Experiments below). This research was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington State University and adhered to the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals.

2.2. Surgery and Microinjections

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus for implantation of a 23-gauge cannula (8 mm long) into the right lateral ventricle. Coordinates were measured from Bregma (AP: −0.8; ML: 1.5; DV: 3.3 mm). Dental cement was used to attach the cannula to two screws placed in the skull. A stylet was inserted into the cannula to maintain patency between injections. Meloxicam was administered at the end of surgery for pain relief. Rats were maintained under a heat lamp until a righting reflex occurred, and then returned to their home cage. Rats were allowed to recover for 7 – 10 days before data collection began.

Rats were weighed and the stylet manipulated daily during the 7 days prior to the beginning of the experiment. On the day of the microinjection, the stylet was removed and a 9 mm injection cannula was inserted protruding 1 mm beyond the end of the guide cannula. Each injection was administered in a volume of 4 μl at a rate of 1 μl/10 s. The large injection volume insured the presence of drug in the lateral ventricle. The injection cannula was removed 20 seconds after the end of the injection, the stylet replaced, and the rat was returned to its home cage.

2.3. Dependent Variables

Voluntary wheel running was used to assess animal well-being. Rotation of the wheel in either direction was recorded with a time stamp using Vital View data acquisition software on a standard PC. Our previous research shows that wheel running is depressed by the side effects of drugs [12,13] and morphine withdrawal [14]. Rats were housed individually in a cage with a running wheel for 2 – 4 days prior to surgery and another 7 – 10 days following surgery prior to the start of the experiment. The number of wheel revolutions on the last day of this habituation period was used as the baseline running level. Running data were not used if a rat did not achieve at least 400 revolutions during the 23 hour baseline period to insure that sufficient levels of running were present to observe a decrease. Wheel running data were collected in 5 min bins, 23 hours a day for 7 to 9 days depending on the experiment. Data analysis focused on the number of wheel revolutions per unit of time (1, 2, 12, or 23 hrs). Body weight was assessed daily during the one-hour period prior to the beginning of the dark phase.

Nociception was assessed using the hot plate test. The latency for a rat to lick a hind paw or jump when placed on a 52.5 °C plate was measured. Baseline nociception was defined as the mean of two baseline trials separated by 10 minutes. The test was terminated and the rat removed from the container if no response occurred within 40 s.

Each cage was monitored with a night vision video camera (Lorex High Definition Security Camera System) 24 hrs a day for 3 days during morphine withdrawal. A point sampling technique was used in which an observer advanced the video to the top of each hour to determine whether each rat was awake or asleep. Sleep was defined as a rat displaying a typical sleep posture (i.e., curled with eyes closed). Data were summed as the total number of times awake for each light and dark phase of the cycle. Observations were conducted blind to the experimental condition.

2.4. Drugs

Morphine sulfate was a gift from the NIDA Drug Supply Program. Morphine was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 5, 10, or 20 mg/ml for subcutaneous administration in a volume of 1 ml/kg. The MOR/DOR heterodimer antagonist D24M was synthesized in Dr. Victor Hruby’s lab at the University of Arizona. D24M uses a 24-atom spacer to link two peptide pharmacophores to block MOR/DOR heterodimers [28]. The drug is dissolved in saline and 2% DMSO at a concentration of 1 or 10 nmol/4 μl. D24M is injected into the lateral ventricle to prevent degradation of the peptide from systemic administration and insure brain access.

2.5. Experiment 1: Assessment of D24M on Wheel Running

The effect of icv administration of the MOR/DOR heterodimer receptor antagonist D24M on home cage wheel running was assessed. A within-subjects design was used in which each rat received an injection of vehicle (2% DMSO in saline), 1 or 10 nmol of D24M on different days. These doses were shown to be selective for the MOR/DOR heterodimer compared to either the MOR or DOR monomer in mice [9]. Injections were administered in a counterbalanced manner with 2 or 3 days between injections. The injection occurred between 30 and 60 min into the dark cycle in the same room as the home cage. Wheel running data was assessed continuously beginning 20 min after the injection. Wheel revolutions were converted to a percent of baseline running using the wheel running data collected during the day preceding each injection as the baseline. Only rats in which data could be collected in all three drug conditions (N = 14) were included in data analysis. Rats were euthanized one day after the last injection.

2.6. Experiment 2: Assessment of Morphine Withdrawal

Different rats were used to assess the effect of icv administration of D24M on morphine tolerance and withdrawal than in Experiment 1. Dependence was induced by administration of twice daily injections of morphine beginning on the day after baseline assessment of wheel running. Injections occurred 10 – 15 min prior to the beginning of the dark phase and again 6 hours later. The same dose was administered for both injections each day. The dose increased from 5 mg/kg/injection on Day 1 to 10 mg/kg/injection on Days 2 & 3 to 20 mg/kg/injection on Day 4 and the morning of Day 5. Control rats received saline injections on the same schedule, volume (1 ml/kg), and route of administration (s.c.). A second injection did not occur on Day 5 so rats could be tested for morphine tolerance.

Morphine tolerance was assessed by injecting all rats with increasing doses of morphine every 20 min resulting in cumulative doses of 2.2, 4.6, and 10 mg/kg, s.c. Nociception was assessed using the hot plate test before and 15 min after each morphine injection. Half of the rats were injected with D24M (1 nmol/4 μl) and half with vehicle into the lateral ventricle following two baseline hot plate tests and again immediately prior to the last morphine injection. The time course for antinociception was assessed by testing rats on the hot plate every 15 min for 75 min following the last morphine injection. The rat was returned to its home cage following each injection. All rats, even those that did not meet the criteria (i.e., 400 baseline revolutions) to be included in the wheel running part of the experiment, were included in hot plate testing. Each condition in this 2 (morphine vs. saline pretreatment) × 2 (D24M vs. vehicle) experimental design contained 10 or 11 rats.

Spontaneous morphine withdrawal was assessed over the next 3 days by continuous video monitoring of whether the rat was asleep or awake and changes in wheel running. The effect of D24M on morphine withdrawal was assessed on the third day of withdrawal. D24M (1 nmol/4 μl) or vehicle was injected icv 30 –60 min into the dark phase. Each rat received the same drug for both the morphine tolerance and withdrawal tests. A timeline for the experiment is shown in Figure 1. Rats were euthanized by isoflurane overdose following the last day of testing.

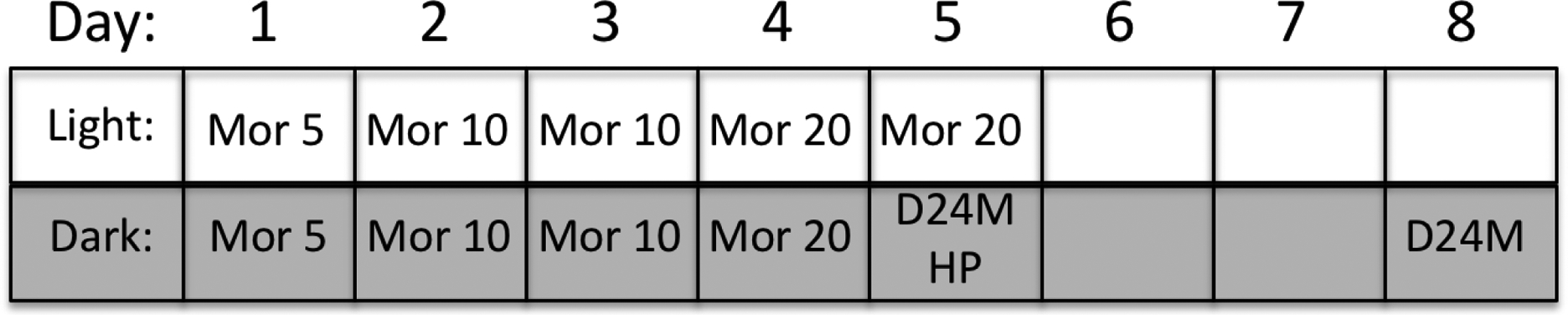

Figure 1:

Timeline for Experiment 2 manipulations. Wheel running data were collected continuously during the dark phase and all but the last hour of the light phase for 9 consecutive days. Baseline activity was assessed for 23 hrs prior to the start of the twice daily injections of increasing doses of morphine (e.g., Mor 5 = 5 mg/kg of morphine) for 5 days. A control group received saline injections on the same schedule (10 – 15 min before the dark cycle and 6 hrs into the dark phase). All rats were tested on the hot plate following microinjection of D24M or vehicle and cumulative doses of morphine 6 hrs into the dark phase on Day 5. Withdrawal was assessed for 3 days (Days 6, 7, & 8). D24M or vehicle was administered 30–60 min into the dark cycle on Day 8.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Wheel running and hot plate data were analyzed using ANOVA in SPSS with an alpha level of .05. Data from Experiment 1 were converted to percent of baseline to control for changes in baseline running across test days. Raw, untransformed data were used in Experiment 2 so the actual wheel running levels and hot plate latencies are evident. GraphPad was used to compare morphine ED50 values for the hot plate latency data.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: Assessment of D24M on Wheel Running

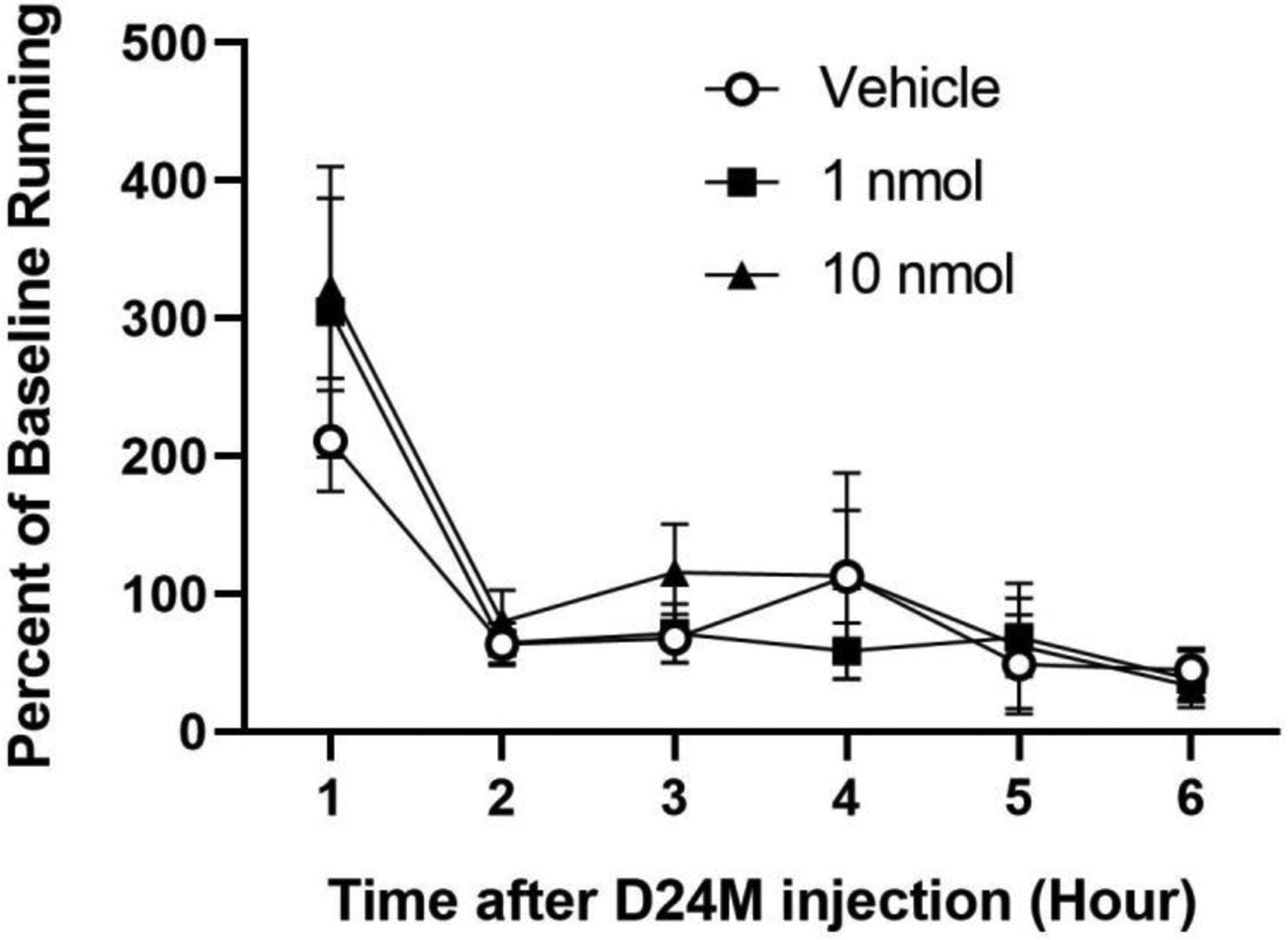

A within-subjects design was used to determine if administration of D24M into the lateral ventricle disrupts home cage wheel running. Mean baseline wheel revolutions in the day prior to the first drug injection was 1490 ± 391 and remained relatively consistent on the baseline days prior to the second (1411 ± 549 revolutions) and third (1507 ± 371 revolutions) injections. To control for individual differences in running, the effect of microinjecting Vehicle or D24M (1 & 10 nmol) is presented as a percent of baseline from the day preceding the injection. Instead of disrupting activity, wheel running tended to be slightly higher in the first hour after D24M administration (Figure 2). However, a one-way ANOVA comparing the three groups during the first hour after the microinjection revealed no significant difference in wheel running (F(2,26) = .674, p = .518).

Fig 2:

Blocking MOR/DOR with the heterodimer antagonist D24M did not disrupt ongoing behavior. Wheel running is presented as a percent of baseline and measured for 6 hrs following icv administration of D24M (1 & 10 nmol/4 μl) or vehicle. The microinjection procedure increased wheel running during the first hour regardless of the drug injection. A within-subjects design was used with 14 rats/condition.

3.2. Experiment 2: Assessment of Morphine Withdrawal

Wheel running data were collected from 31 of the 42 rats. Rats that did not have at least 400 revolutions on the baseline day (N = 10) or a computer error prevented assessment (N = 1) were only used for the hot plate part of the experiment. The mean baseline revolutions for the 31 wheel-running rats was 1261 ± 160. Eighty percent of this running occurred during the dark phase of the circadian cycle. Because of this large difference in running, the effects of morphine and morphine withdrawal on wheel running during the dark and light phases of the circadian cycle were analyzed separately.

Baseline wheel running was comparable in the morphine and saline treated groups (Figure 3). Administration of morphine significantly depressed wheel running compared to saline treated rats during the dark phase (F(1,29) = 5.046, p = .032; Figure 3 Left). There was no effect of morphine administration on wheel running during the light phase (F(1,29) = 0.845, p = .365; Figure 3 Right) because baseline levels of running were low and the last morphine injection each day was 6 hours before the beginning of the light phase.

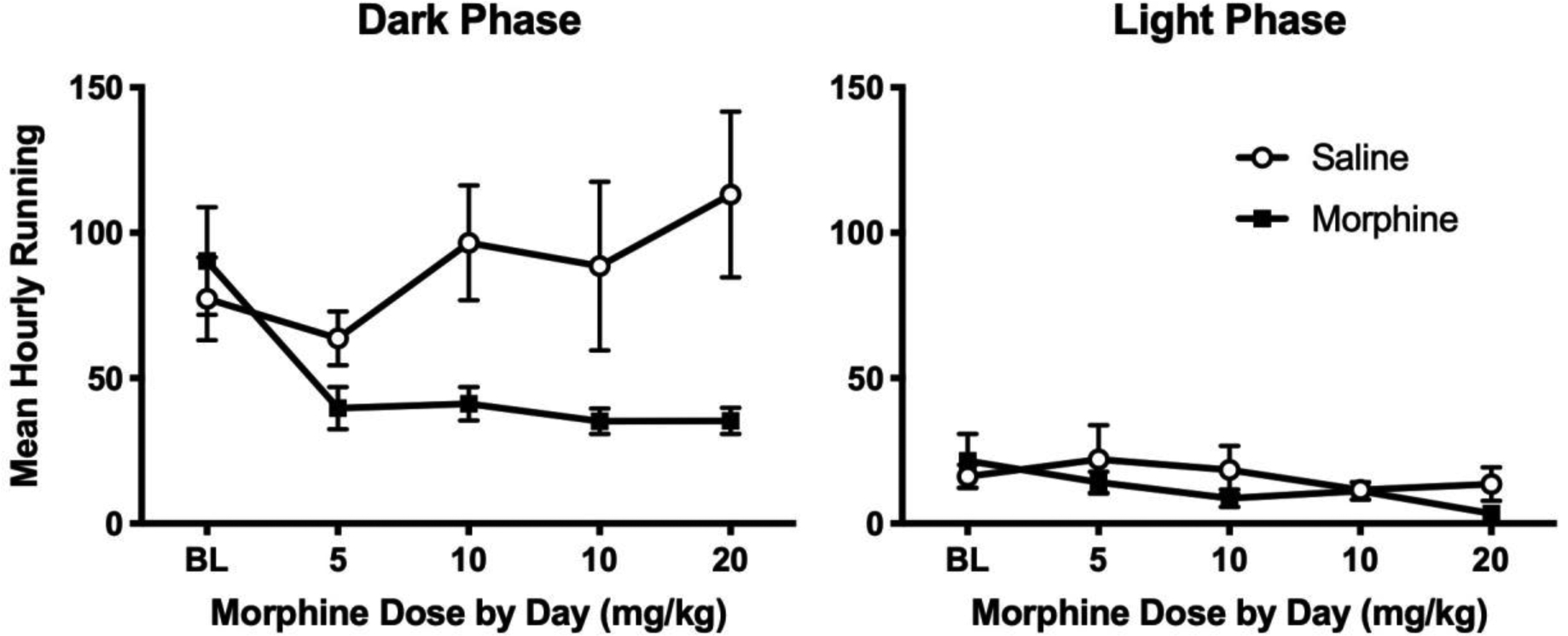

Figure 3:

Morphine administration deceases home cage wheel running during the dark (left), but not the light (right) phase of the circadian cycle. Rats were injected with saline (N = 14) or increasing doses of morphine (N = 17) twice a day (see Figure 4 for 2 hr data). Data are presented as average hourly running so the 12 hrs of data collection during the dark phase can be compared to the 10 hrs of data collection during the light phase. Data from the last 2 hrs of the light phase are not used because of a dramatic increase in activity that occurs in the hour before rats are weighed and injected.

A more complete understanding of the effects of morphine administration requires viewing these data in 2 hr blocks (Figure 4). Rats were consistently more active during the first 6 hrs of the dark phase than at later time points. A decrease in wheel running occurred on the first day of injections in both morphine and saline treated rats compared to baseline levels of running. Wheel running returned to baseline levels in saline treated rats on subsequent days. In contrast, morphine administration depressed wheel running throughout the dark phase on all of the injection days. This decrease in activity is particularly noticeable in the 2 hrs following each of the two morphine injections (e.g., the 2 and 8 hr time points). The magnitude of the decrease in activity is comparable across days despite an increase in morphine dose from 5 to 20 mg/kg. Data from the Day 5 injection of morphine are not shown because all rats were tested with morphine on the hot plate during the second half of the dark phase.

Fig 4:

Time course for depression of wheel running caused by morphine injections. Each graph displays total wheel revolutions in 2 hr blocks during the dark phase on consecutive days. Rats were injected with morphine (N = 17) or saline (N = 14) 10 – 15 min prior to the beginning of the dark phase and again 6 hrs later (see arrows). Activity was relatively low in both morphine and saline injected groups on the first day, suggesting an effect of the novelty or stress of the injection. On subsequent days, injections of 10 and 20 mg/kg of morphine caused consistent decreases in wheel running. These decreases were greatest during the 2 hrs after the injection, but rats given morphine were also less active between injections. No injections were administered on the baseline day.

Tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of morphine was assessed using the hot plate test 6 hours after the last morphine injection on Day 5 (see Experimental design in Figure 1). Baseline hot plate latency was similar whether rats had been treated with saline or morphine for the previous 4.5 days (14.7 ± 0.8 and 15.2 ± 0.8 s, respectively). Administration of D24M had no effect on hot plate latency compared to vehicle treated rats (Vehicle = 12.0 ± 0.8 vs. D24M = 12.5 ± 0.7 s; t(40) = 0.516, p = .609). Dose response analysis revealed that groups pretreated with morphine had significantly higher morphine ED50 values (88.0 and 30.3 mg/kg for rats treated with vehicle and D24M) than rats pretreated with saline (9.5 and 7.2 mg/kg for rats treated with vehicle and D24M; F(3,118) = 8.08, p < .001). Administration of cumulative morphine doses of 10 mg/kg caused a significant increase in hot plate latency for rats that had been treated previously with saline compared to rats pretreated with morphine (F(1,38) = 16.014, p < .001; Figure 5 left). Microinjection of D24M into the lateral ventricle did not significantly alter hot plate latency in morphine tolerant or morphine naïve rats (F(1,38) = 1.857, p = .181).

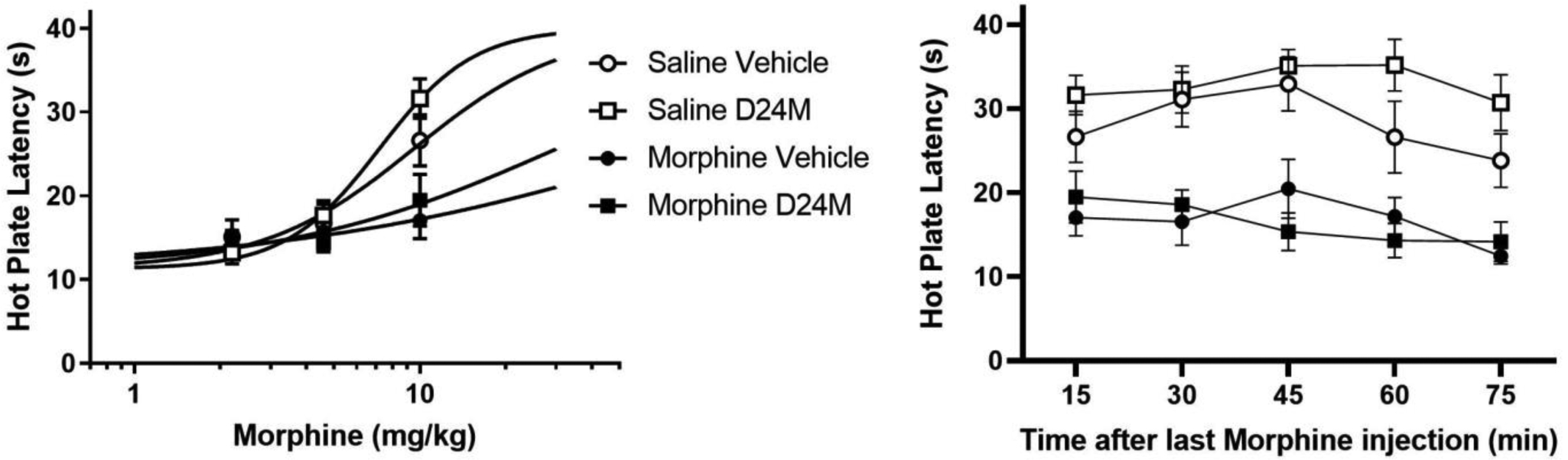

Figure 5:

Administration of D24M did not alter morphine antinociception in morphine tolerant or non-tolerant rats. Left: Following baseline hot plate measurements, rats were injected with D24M or vehicle into the lateral ventricle. Fifteen minutes after the icv injection, rats were injected with increasing doses of morphine subcutaneously. A cumulative dose of 10 mg/kg increased hot plate latency in rats pretreated with saline compared to rats pretreated with morphine for 4.5 days. Right: Antinociception persisted for over 1 hr following the last morphine injection. Administration of D24M appears to prolong antinociception in morphine naïve rats, but this effect was not statistically significant. N = 10 – 11/condition.

A significant decrease in hot plate latency occurred over the 75 min time period following the last morphine injection (F(4,152) = 4.109, p = .003; Figure 5 right). This reduction in morphine antinociception appears to be delayed by administration of D24M in rats receiving morphine for the first time (Figure 5 right), but this increase in hot plate latency at the 60 min time point did not reach statistical significance compared to vehicle treated rats (t(19) = 1.364, p = .118).

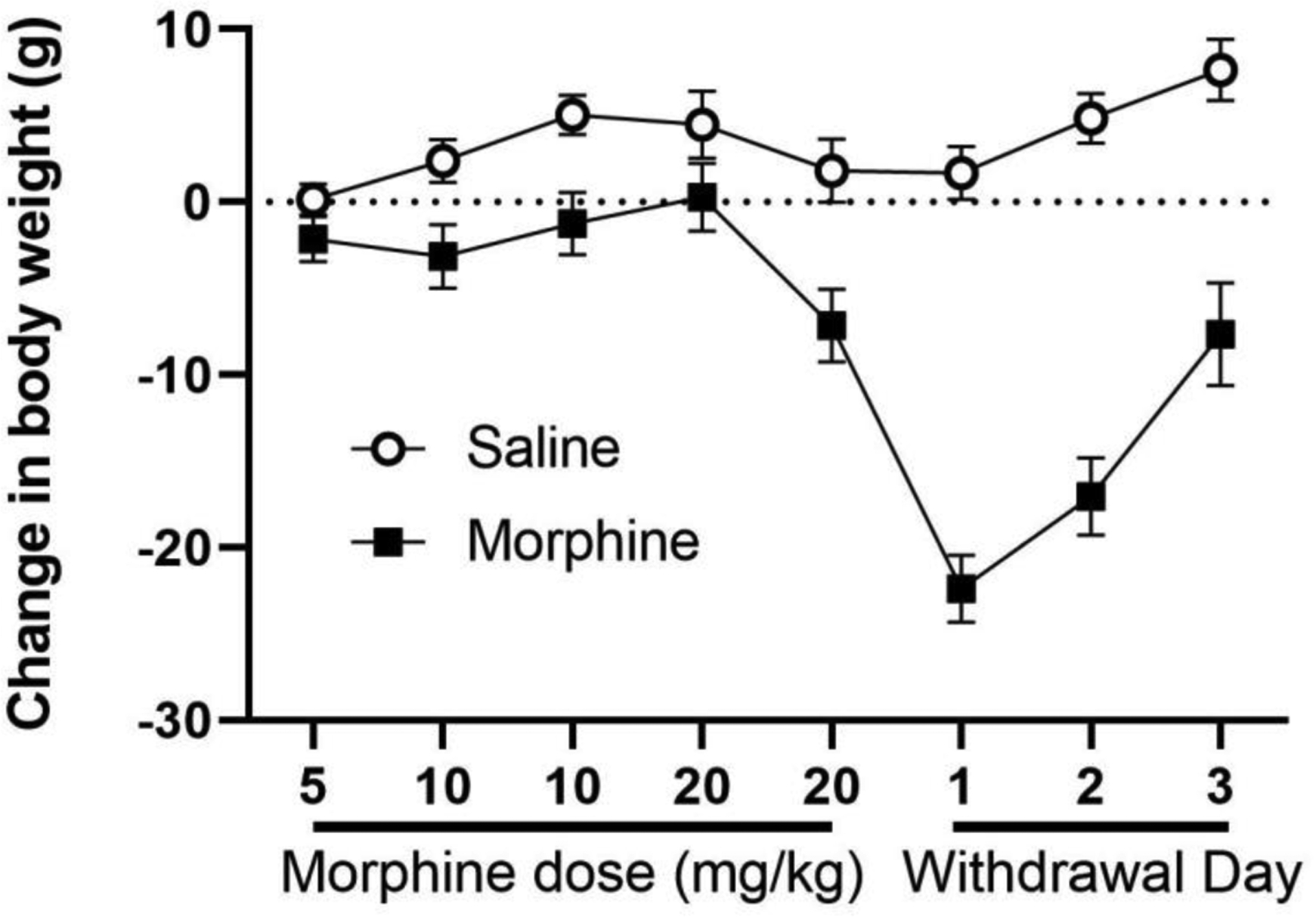

Spontaneous morphine withdrawal was evident as changes in body weight, wheel running, and wakefulness. Mean body weight was nearly identical prior to morphine (295 ± 4 g) and saline (297 ± 4 g) injections. Repeated morphine injections caused a slight reduction in body weight compared to saline treated rats, but these changes were trivial compared to the decrease in weight on the day following the last morphine injection (Figure 6). ANOVA covering the three days of withdrawal revealed a significant decrease in body weight for rats previously treated with morphine compared to rats previously treated with saline (F(1,40) = 68.900, p < .001).

Figure 6:

Morphine withdrawal caused a decrease in body weight. Body weight is presented as a daily change from baseline weight in grams. Repeated morphine injections decreased body weight compared to rats receiving repeated saline injections (N = 21 in each group). Both groups were injected with cumulative injections of morphine (10 mg/kg) on the afternoon of the last day of morphine and saline injections (Mor 20) to assess tolerance on the hot plate test. A large decrease in body weight is evident on the 3 days following the last morphine injection in rats pretreated with morphine compared to saline. Each day is designated by morphine injection (e.g., Mor 5 = two injections of 5 mg/kg morphine) or day of withdrawal (e.g., With 1).

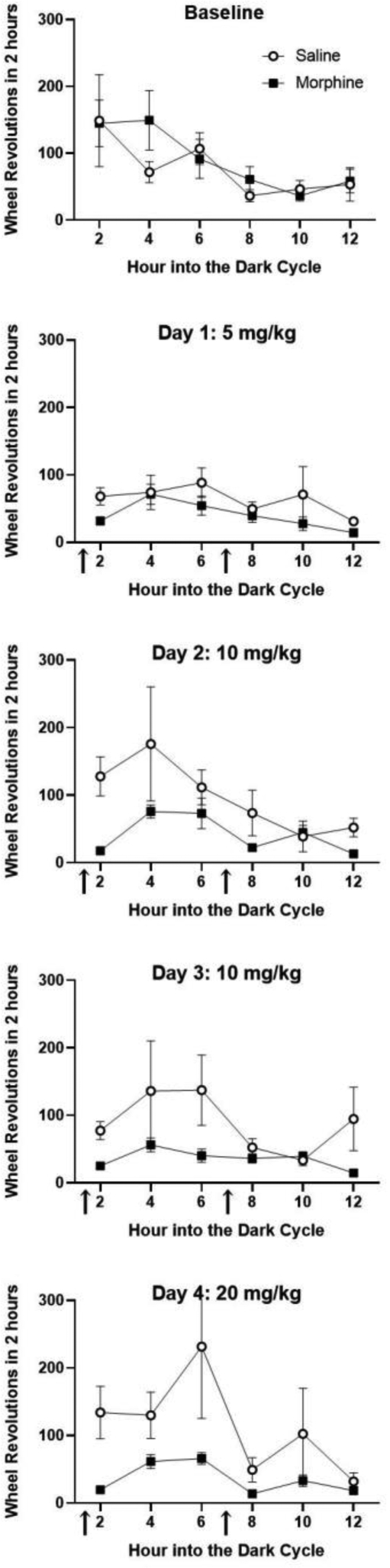

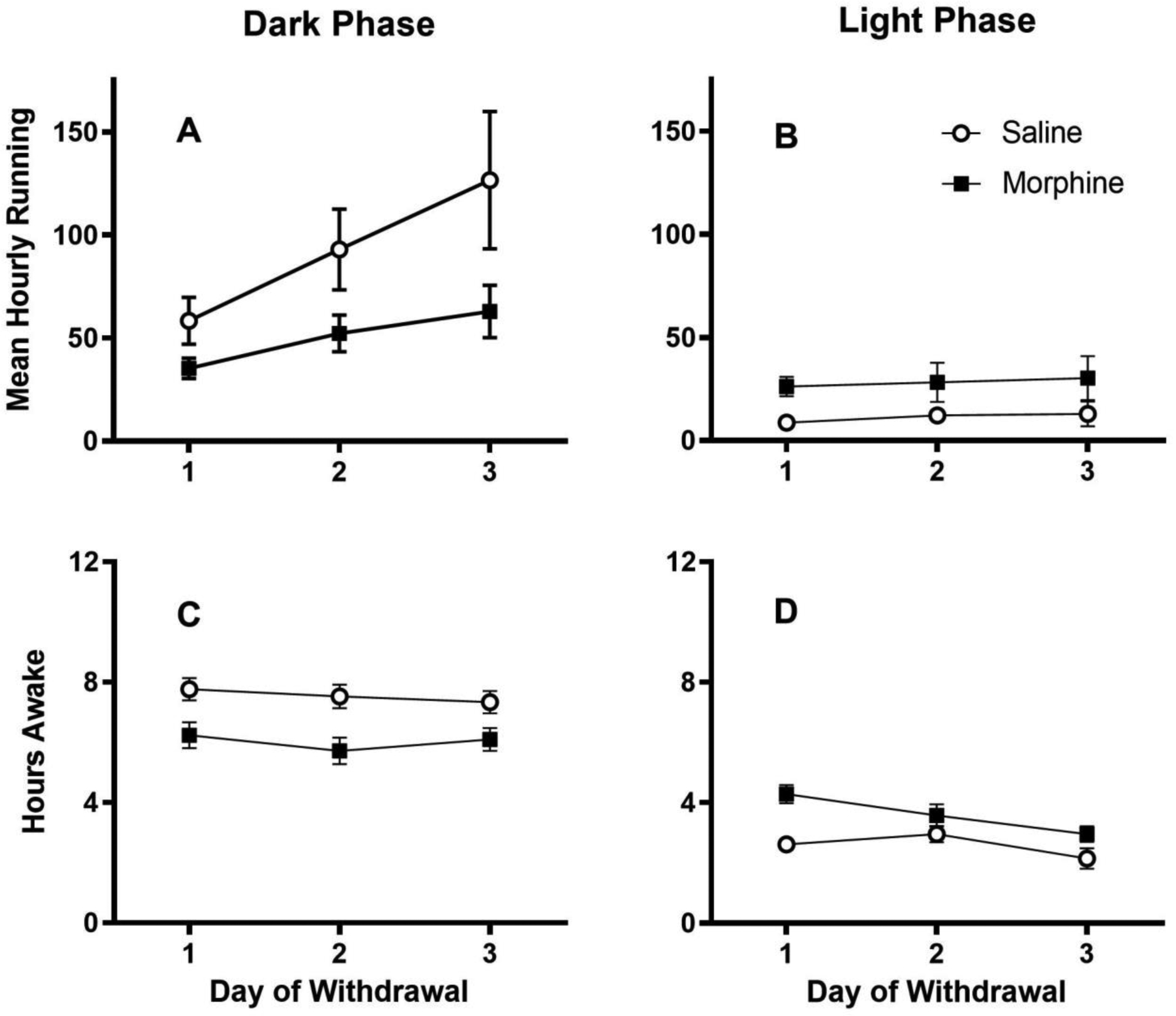

Morphine withdrawal produced opposite effects on home cage wheel running depending on whether activity was analyzed during the dark or light phase. Rats pretreated with morphine for 5 days showed a significant decrease in wheel running during the dark phase on the 3 days following the last injection compared to rats pretreated with saline ((1,29) = 4.707, p = .038; Figure 7A). In contrast, these same morphine withdrawal rats were more active during the light phase of the circadian cycle compared to saline treated controls (Figure 7B). Running levels were very low during the light phase so this difference between groups was at the threshold for statistical significant (F(1,29) = 3.990, p = .055).

Figure 7:

Opposite changes in dark and light cycle wheel running and wakefulness caused by morphine withdrawal. A) Rats undergoing morphine withdrawal following termination of repeated morphine injections were less active during the dark phase of the cycle than rats previously receiving repeated saline injections. B) In contrast, morphine withdrawal caused an increase in wheel running during the normally quiet light phase compared to saline pretreated control rats. N = 14 and 17 rats for the saline and morphine pretreated groups, respectively. Data are presented as average hourly wheel running to allow comparison between the 12 hrs of data collection during the dark phase (total revolutions/12 hrs) and the 10 hrs of data collection during the light phase (total revolutions/10 hrs). Changes in activity were consistent with morphine withdrawal induced changes in wakefulness. Video monitoring was used to assess whether each rat was awake or asleep at the beginning of each hour for the 3 days of morphine withdrawal. Morphine withdrawal caused rats to be asleep during the dark phase (C) and awake during the light phase (D) compared to saline pretreated control rats. Wakefulness was assessed in 21 rats in each condition.

The changes in wheel running caused by morphine withdrawal corresponded to changes in the amount of time rats were awake. Rats are nocturnal so it is not surprising that saline treated control rats spent over twice as much time asleep during the light phase than the dark phase of the circadian cycle. Termination of morphine administration caused a significant reduction in the amount of time rats were awake during the dark phase compared to saline treated controls (F(1,40) = 13.181, p = .001; Figure 7C). In contrast, rats undergoing morphine withdrawal spent significantly more time awake during the light phase compared to saline treated controls (F(1,40) = 11.851, p = .001; Figure 7D).

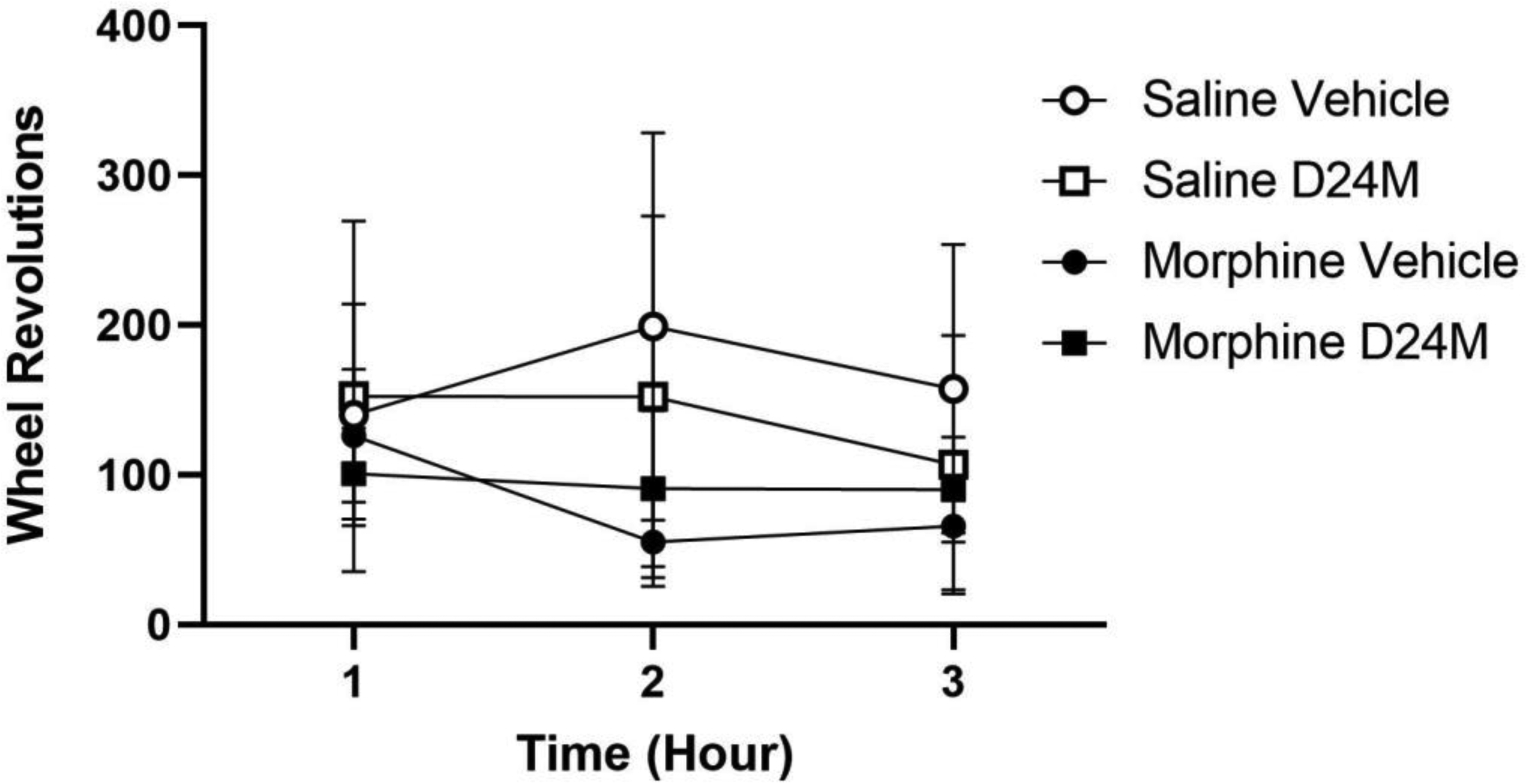

The effect of icv administration of D24M on morphine withdrawal was assessed for 3 hrs at the beginning of the dark phase on Day 3 of withdrawal. As described above (Figure 7A), rats undergoing morphine withdrawal were less active than rats pretreated with saline. This difference was also evident in the 3 hrs following D24M administration (Figure 8). Although administration of D24M reduced running in saline-pretreated rats and increased running in morphine tolerant rats, this interaction between D24M and the morphine/saline pretreatment was not statistically significant (F(1,28) = .079. p =.781).

Fig 8:

Microinjection of D24M did not restore activity depressed by morphine withdrawal. D24M or vehicle was injected into the lateral ventricle during the dark phase of Day 3 of withdrawal. Rats undergoing morphine withdrawal were less active than rats pretreated with saline, but there was no significant effect of D24M (F(1,28) = .014, p =.907) and no significant interaction between D24M and morphine treatment (F(1,28) = .079. p =.781). N = 7 – 9/condition.

4. Discussion

The two main findings of this study are that home cage wheel running is an objective and accurate method to assess spontaneous morphine withdrawal and administration of the MOR/DOR heterodimer antagonist D24M does not disrupt normal activity or inhibit morphine antinociception. Spontaneous morphine withdrawal caused a decrease in body weight, a decrease in wakefulness and wheel running during the dark phase, and an increase in wakefulness and wheel running during the light phase of the circadian cycle. Administration of D24M into the lateral ventricle did not disrupt wheel running when administered alone, did not inhibit morphine antinociception, and did not alter morphine withdrawal. In fact, administration of D24M tended to increase wheel running and prolong morphine antinociception.

The current opioid crisis, in which millions of Americans are dependent on opioids and 42,000 died of an overdose in 2016 [1], has focused attention on the need for novel treatments for pain that do not cause dependence and methods to treat opioid withdrawal. Despite thousands of animal studies, the development of novel treatments for pain or opioid withdrawal has largely failed. This lack of translation raises questions about the clinical relevance of animal models. We designed this experiment to mimic the intermittent opioid use and spontaneous withdrawal that is common to opioid abuse in humans. A key part of this was the continuous assessment of spontaneous opioid withdrawal in the rat’s home environment.

The assessment of spontaneous opioid withdrawal is a challenge because symptoms tend to be mild and dispersed over time compared to the profound somatic symptoms that occur immediately following precipitation of withdrawal with administration of the opioid receptor antagonist naloxone. Nonetheless, a surprisingly wide range of spontaneous withdrawal symptoms have been reported. These include a decrease in body weight [15], reduction in home cage movement [16–18], disruption of circadian rhythm [16], hyperalgesia [19], decreased memory and cognitive function [20], increased anxiety and depression [21–23], and the occurrence of somatic withdrawal symptoms in rodents such as jumping and shaking [19,24].

Our previous research added to this list by showing that spontaneous withdrawal following continuous morphine administration depresses voluntary home cage wheel running [14]. Our present data extend this finding in three ways. First, the daily depression of wheel running is caused by a large decrease during the active dark phase and a smaller increase in wheel running during the light phase. Well-known circadian differences in wheel running [25] indicate that changes during the light and dark phases should be examined separately. Second, these changes in wheel running occur with 5 days of intermittent morphine administration in addition to the continuous morphine administration in our previous study [14]. And finally, these changes in wheel running correspond to other withdrawal symptoms such as changes in wakefulness and loss of body weight. Home cage wheel running is an especially useful method to assess withdrawal because it is objective and easy to quantify, is conducted in the animal’s home cage, and provides a continuous assessment of the magnitude and duration of withdrawal. Exercise has been shown to attenuate opioid withdrawal [26,27], indicating that the present withdrawal symptoms may be more severe than shown.

Home cage wheel running is also a useful tool to screen potential treatments for opioid withdrawal because an effective treatment is defined by its ability to restore normal activity, not inhibit somatic withdrawal symptoms. Many drugs (e.g., anesthetics, paralytics) will inhibit somatic withdrawal symptoms, but this inhibition is merely masking symptoms, not treating withdrawal. In contrast, neither anesthetics nor paralytics will restore wheel running depressed by opioid withdrawal. The restoration of activity is a difficult criterion for a drug to attain because it must reduce the symptoms of withdrawal in the absence of producing negative effects. The difficulty in attaining this criterion is demonstrated by our assessment of the MOR/DOR heterodimer antagonist D24M.

In our previous work in mice, D24M at this dose significantly reduced the somatic signs of naloxone-precipitated withdrawal from morphine [9]. There are many potential reasons why administration of D24M did not have the same effect in the present study. 1) Differences between mice and rats could cause differences in opioid dependence or sensitivity to D24M. 2) Restoration of wheel running requires an increase in behavior instead of the easier to attain suppression of withdrawal behaviors. 3) Exercise, or the lack of exercise in mice, could influence the formation of the MOR/DOR heterodimer. 4) Repeated co-administration of D24M and morphine may be more effective than a single injection after dependence has developed. And 5) The extended nature of spontaneous withdrawal raises questions about the timing of D24M injections compared to the immediate withdrawal behavior precipitated by naloxone administration. In the present rat study, D24M was administered on the third day of withdrawal, whereas D24M administration preceded naloxone administration in the previous mouse study. These hypotheses will be tested in future experiments.

The present data show that administration of D24M into the lateral ventricle had no negative effects. Whether this is because D24M is inactive in rats or just innocuous is difficult to know. D24M did not depress wheel running when administered alone and did not disrupt morphine antinociception. In contrast, D24M tended to enhance wheel running and prolong morphine antinociception. The lack of inhibition of D24M on wheel running is noteworthy because standard doses of other drugs used to inhibit pain-evoked responses in rats (e.g., morphine and THC) cause a decrease in home cage wheel running [12,13]. Restoration of wheel running depressed by pain required low doses of morphine and THC that reduced pain in the absence of disruptive side effects.

Although previous research showed that administration of D24M in mice blocked the antinociceptive effect of a MOR/DOR agonist [9], the present study showed that D24M administration did not block morphine antinociception. Despite this difference, both results show that D24M is not necessary for antinociception. Although the formation of the MOR/DOR heterodimer with repeated opioid administration suggests a role in morphine tolerance and/or dependence [2–5], the present data found no effect of D24M on morphine tolerance. Moreover, administration of D24M had no effect on wheel running depressed by morphine withdrawal.

The lack of an effect of D24M on morphine tolerance and withdrawal in the present study is not conclusive. It is possible that MOR/DOR is only recruited when more severe tolerance and dependence occurs such as with administration of higher doses of morphine, longer treatment regimens, or continuous administration. The presence of chronic pain could also facilitate engagement of the MOR/DOR heterodimer. Finally, recent studies on ligand biased signaling [28] indicate that MOR/DOR signaling may vary depending on the opioid. Both morphine or fentanyl produces antinociception when injected into the periaqueductal gray, but cross-tolerance is limited between these opioids [29]. Morphine and fentanyl appear to produce tolerance via different mechanisms [30,31]. We are currently in the process of testing the effects of D24M on tolerance and withdrawal induced by different opioids and administration regimens in rats with persistent pain.

Highlights.

Morphine injections and morphine withdrawal decreased home cage wheel running

Morphine withdrawal decreased body weight and disrupted sleep during the light phase

The MOR/DOR heterodimer antagonist, D24M, did not disrupt wheel running

ICV administration of D24M did not block morphine antinociception or withdrawal

Acknowledgements:

Data collection for Experiment 1 was conducted by Kristin Ataras. Jonah Stickney constructed the graphs. The gift of D24M was provided by Zekun Liu and Victor Hruby. Morphine sulfate was a gift from the NIDA Drug Supply Program.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number UG3 DA047717]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest:

JMS has an Equity stake in Botanical Results, LLC.

Reference

- [1].Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM, Prevention and Treatment of Opioid Misuse and Addiction: A Review, JAMA Psychiatry. 76 (2019) 208–216. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Charles AC, Mostovskaya N, Asas K, Evans CJ, Dankovich ML, Hales TG, Coexpression of delta-opioid receptors with micro receptors in GH3 cells changes the functional response to micro agonists from inhibitory to excitatory, Mol. Pharmacol 63 (2003) 89–95. 10.1124/mol.63.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gomes I, Jordan BA, Gupta A, Trapaidze N, Nagy V, Devi LA, Heterodimerization of mu and delta opioid receptors: A role in opiate synergy, J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci 20 (2000) RC110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jordan BA, Devi LA, G-protein-coupled receptor heterodimerization modulates receptor function, Nature. 399 (1999) 697–700. 10.1038/21441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rozenfeld R, Devi LA, Receptor heterodimerization leads to a switch in signaling: beta-arrestin2-mediated ERK activation by mu-delta opioid receptor heterodimers, FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol 21 (2007) 2455–2465. 10.1096/fj.06-7793com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Milan-Lobo L, Enquist J, van Rijn RM, Whistler JL, Anti-analgesic effect of the mu/delta opioid receptor heteromer revealed by ligand-biased antagonism, PloS One. 8 (2013) e58362 10.1371/journal.pone.0058362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fujita W, Gomes I, Dove LS, Prohaska D, McIntyre G, Devi LA, Molecular characterization of eluxadoline as a potential ligand targeting mu-delta opioid receptor heteromers, Biochem. Pharmacol 92 (2014) 448–456. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gomes I, Fujita W, Gupta A, Saldanha SA, Saldanha AS, Negri A, Pinello CE, Eberhart C, Roberts E, Filizola M, Hodder P, Devi LA, Identification of a μ-δ opioid receptor heteromer-biased agonist with antinociceptive activity, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110 (2013) 12072–12077. 10.1073/pnas.1222044110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Olson KM, Keresztes A, Tashiro JK, Daconta LV, Hruby VJ, Streicher JM, Synthesis and Evaluation of a Novel Bivalent Selective Antagonist for the Mu-Delta Opioid Receptor Heterodimer that Reduces Morphine Withdrawal in Mice, J. Med. Chem 61 (2018) 6075–6086. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kandasamy R, Calsbeek JJ, Morgan MM, Home cage wheel running is an objective and clinically relevant method to assess inflammatory pain in male and female rats, J. Neurosci. Methods 263 (2016) 115–122. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kandasamy R, Lee AT, Morgan MM, Depression of home cage wheel running: a reliable and clinically relevant method to assess migraine pain in rats, J. Headache Pain 18 (2017) 5 10.1186/s10194-017-0721-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kandasamy R, Calsbeek JJ, Morgan MM, Analysis of inflammation-induced depression of home cage wheel running in rats reveals the difference between opioid antinociception and restoration of function, Behav. Brain Res 317 (2017) 502–507. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kandasamy R, Dawson CT, Craft RM, Morgan MM, Anti-migraine effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the female rat, Eur. J. Pharmacol 818 (2018) 271–277. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kandasamy R, Lee AT, Morgan MM, Depression of home cage wheel running is an objective measure of spontaneous morphine withdrawal in rats with and without persistent pain, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 156 (2017) 10–15. 10.1016/j.pbb.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bobzean SAM, Kokane SS, Butler BD, Perrotti LI, Sex differences in the expression of morphine withdrawal symptoms and associated activity in the tail of the ventral tegmental area, Neurosci. Lett 705 (2019) 124–130. 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stinus L, Robert C, Karasinski P, Limoge A, Continuous quantitative monitoring of spontaneous opiate withdrawal: locomotor activity and sleep disorders, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 59 (1998) 83–89. 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].van der Laan JW, van ‘t Land CJ, Loeber JG, de Groot G, Validation of spontaneous morphine withdrawal symptoms in rats, Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther 311 (1991) 32–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].van der Laan JW, de Groot G, Changes in locomotor-activity patterns as a measure of spontaneous morphine withdrawal: no effect of clonidine, Drug Alcohol Depend. 22 (1988) 133–140. 10.1016/0376-8716(88)90048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Balter RE, Dykstra LA, Thermal sensitivity as a measure of spontaneous morphine withdrawal in mice, J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 67 (2013) 162–168. 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mokhtari-Zaer A, Ghodrati-Jaldbakhan S, Vafaei AA, Miladi-Gorji H, Akhavan MM, Bandegi AR, Rashidy-Pour A, Effects of voluntary and treadmill exercise on spontaneous withdrawal signs, cognitive deficits and alterations in apoptosis-associated proteins in morphine-dependent rats, Behav. Brain Res 271 (2014) 160–170. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harris AC, Gewirtz JC, Elevated startle during withdrawal from acute morphine: a model of opiate withdrawal and anxiety, Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 171 (2004) 140–147. 10.1007/s00213-003-1573-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mohammadian J, Miladi-Gorji H, Age- and sex-related changes in the severity of physical and psychological dependence in morphine-dependent rats, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 187 (2019) 172793 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.172793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rauf K, Subhan F, Abbas M, Ali SM, Ali G, Ashfaq M, Abbas G, Inhibitory effect of bacopasides on spontaneous morphine withdrawal induced depression in mice, Phytother. Res. PTR 28 (2014) 937–939. 10.1002/ptr.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li S, Liu L, Jiang W, Lu L, Morphine withdrawal produces circadian rhythm alterations of clock genes in mesolimbic brain areas and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in rats, J. Neurochem 109 (2009) 1668–1679. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eikelboom R, Mills R, A microanalysis of wheel running in male and female rats, Physiol. Behav 43 (1988) 625–630. 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alizadeh M, Zahedi-Khorasani M, Miladi-Gorji H, Treadmill exercise attenuates the severity of physical dependence, anxiety, depressive-like behavior and voluntary morphine consumption in morphine withdrawn rats receiving methadone maintenance treatment, Neurosci. Lett 681 (2018) 73–77. 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Miladi-Gorji H, Rashidy-Pour A, Fathollahi Y, Akhavan MM, Semnanian S, Safari M, Voluntary exercise ameliorates cognitive deficits in morphine dependent rats: the role of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor, Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 96 (2011) 479–491. 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kelly E, Ligand bias at the μ-opioid receptor, Biochem. Soc. Trans 41 (2013) 218–224. 10.1042/BST20120331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bobeck EN, Schoo SM, Ingram SL, Morgan MM, Lack of Antinociceptive Cross-Tolerance With Co-Administration of Morphine and Fentanyl Into the Periaqueductal Gray of Male Sprague-Dawley Rats, J. Pain Off. J. Am. Pain Soc 20 (2019) 1040–1047. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Melief EJ, Miyatake M, Bruchas MR, Chavkin C, Ligand-directed c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation disrupts opioid receptor signaling, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107 (2010) 11608–11613. 10.1073/pnas.1000751107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Morgan MM, Reid RA, Saville KA, Functionally selective signaling for morphine and fentanyl antinociception and tolerance mediated by the rat periaqueductal gray, PloS One. 9 (2014) e114269 10.1371/journal.pone.0114269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]