Abstract

Background

Infected diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) patients present with an impaired baseline physical function (PF) that can be further compromised by surgical intervention to treat the infection. The impact of surgical interventions on Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) PF within the DFU population has not been investigated. We hypothesize that preoperative PROMIS scores (PF, Pain Interference (PI), Depression) in combination with relevant clinical factors can be utilized to predict postoperative PF in DFU patients.

Methods

DFU patients from a single academic physician’s practice between February 2015 and November 2018 were identified (n=240). Ninety-two patients met inclusion criteria with complete follow-up and PROMIS computer adaptive testing records. Demographic and clinical factors, procedure performed, and wound healing status were collected. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, Chi-Squared tests and multidimensional modelling were applied to all variables’ pre- and postoperative values to assess patients’ postoperative PF.

Results

The mean age was 60.5 (33–96) years and mean follow-up was 4.7 (3–12) months. Over 70% of the patients’ initial PF were 2 to 3 standard deviations below the US population (n = 49; 28). Preoperative PF (p < 0.01), PI (p < 0.01), Depression (p < 0.01), CRF (p < 0.02) and amputation level (p < 0.04) showed significant univariate correlation with postoperative PF. Multivariate model (r = 0.55) showed that the initial PF (p = 0.004), amputation level (p = 0.008), and wound healing status (p = 0.001) predicted postoperative PF.

Conclusions

Majority of DFU patients present with poor baseline PF. Preoperative PROMIS scores (PF, PI, Depression) are predictive of postoperative PROMIS PF in DFU patients. Postoperative patient’s physical function can be assessed by PFpostoperative = 29.42 + 0.34 (PFinitial) – 5.87 (Not Healed) – 2.63 (Amputation Category). This algorithm can serve as a valuable tool for predicting post-operative physical function and setting expectations.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcer, patient-reported outcomes, PROMIS, physical function, predictive outcome

INTRODUCTION

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a set of person-centered measures developed by the National Institute of Health (NIH) that assesses and monitors the overall health of patients1. PROMIS questions are developed based on item-response theory (IRT) and domains of health such as physical function (PF), pain interference (PI), and Depression. PROMIS can be administered through computer adaptive testing (CAT) to select optimal items to increase acuity in estimating one’s status based upon their earlier responses2,3. Together, IRT and CAT provide PROMIS added precision and versatility that builds upon conventional static patient-reported surveys4–6.

The implementation of CAT-enabled PROMIS for research and for clinical applications is gaining popularity7–12. PROMIS allows for efficient and accurate measures in specific patient populations while permitting standardized and comparable score across different clinical disciplines and studies. The questions are designed to be easily understood by an audience of a wide education level, increasing its accuracy in diverse populations13. In particular, PROMIS PF measure was more efficient to administer than Foot and Ankle Ability Measure-Activity of Daily Living subscale (FAAM_ADL), FAAM sports module (spFAAM), and Foot Function Index (FFI)14–16 in foot and ankle patients. Moreover, PROMIS domains such as PI, and Depression have shown high validity and reliability5,17–23. Preoperative PROMIS scores have shown to predict postoperative improvements in foot and ankle patients7,24. Preoperative PROMIS scores were also highly predictive in postoperative improvements for primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery25, total hip arthroplasty (THA)26, hand surgery27, total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA)28, and lumbar discectomy29. However, the clinical application of PROMIS in diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) patients remains unexplored.

DFU is a predominant global health issue with a global prevalence rate of 6.3% and 13% in the US30–32. DFU patients are often immunocompromised as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM) impairs T- and B-cells33. DM patients frequently have comorbid chronic conditions, such as hypertension, peripheral neuropathy (PN), renal diseases, and peripheral arterial disease32,34,35, all of which make this population a unique and challenging cohort to study and treat. Infected DFU, if delayed or left untreated, may lead to devasting outcomes such as a limb loss. A prolonged course of treatment can further limit the patient’s already hampered quality of life and physical function36,37. When presented to a physician’s office, the majority of DFU patients have significantly compromised mobility secondary to peripheral neuropathy, foot deformity, partial foot amputation from previous treatment, and ulceration with or without infection. At times, patients’ misperception in the projected loss of PF post amputation may pose challenge in obtaining consent and delay in proceeding with an appropriate surgical care. Given such challenges, we sought to investigate the applicability of PROMIS to accurately assess baseline PF and predict postoperative PF in a numeric value to facilitate patient’s understanding for pre-operative counseling and consenting process. We aimed to evaluate: 1) the baseline clinical and PROMIS symptom characteristics of DFU patients, 2) the associations of clinical variables and PROMIS symptom scales with postoperative PROMIS PF and 3) the predictive value of preoperative PROMIS (PF, PI, and Depression) scores coupled with relevant clinical variables on postoperative PF. We hypothesized that the preoperative PROMIS scores in combination with relevant clinical factors can predict postoperative PF.

METHODS

Participants

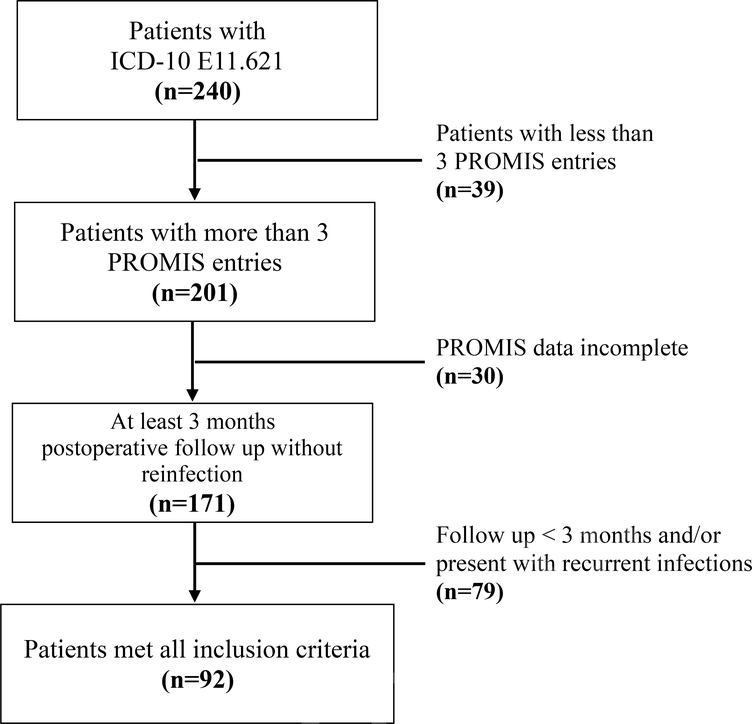

DFU patients who visited a single academic physician’s practice between February 2015 and November 2018 were identified using ICD-10 code E11.621. Patients who required a concomitant or delayed reconstruction procedure due to severe foot deformity were excluded. A total 240 patients were identified. Patients with at least 3 consecutive visits, underwent a procedural intervention (wound debridement and/or amputations), 3 months minimum post-surgical follow-up and completed PROMIS CAT assessments for each visit were included. We excluded patients who developed post-surgical recurrent infection or wound complication that required additional surgical interventions within the minimum follow-up (3 months) period as additional interventions impacts PROMIS PF score (Figure 1). Ninety-two patients met the inclusion criteria and formed the basis of this study.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Patient Selection.

Clinical and Outcome Variables

Clinical variables were extracted from the electronic medical record and PROMIS database. Demographic data, BMI, medical comorbidities (e.g. chronic renal failure (CRF) and clinical diagnosis of depression), hemoglobin A1c (HbAlc), procedure performed, and wound healing status were collected. Amputation level was categorized as the following: irrigation and debridement (I&D) as 0 (n=39), forefoot amputations (n=46) as 1, mid or hindfoot amputations (n=14) as 2, and Syme or above amputations (n=12) as 3. Medical comorbidities and healing status were considered as dichotomous attributes (healed = 0, not healed = 1). Finally, a thorough chart review and physical exam (5.07G monofilament test) were conducted to diagnose or document presence of PN38–40. Patients completed PROMIS CAT assessment in the waiting area, including PROMIS Bank Pain Interference (v1.1), PROMIS Bank physical Function (v2.0), and PROMIS Bank Depression (v1.0) measures41–43.

Statistical Analysis

First (Aim 1), descriptive statistics were reported for clinical and PROMIS variables. In checking for normality, the PROMIS Depression scale was not normally distributed. Therefore, non-parametric analysis was pursued for this variable. To describe the prevalence of symptom severity, the PROMIS scales were converted to ordinal data by categorizing patients by standard deviation increments better or worse than the US general population.

To assess univariate associations of baseline variables, chi-square and spearman rho correlations were used (Aim 2). The association of dichotomous clinical variables (i.e. gender, CRF, amputation level, and healing status) with PROMIS PF (ordinal scale) was assessed with a chi-squared test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to assess correlation among PROMIS scales (continuous data). Alpha level was set at 0.05.

Multivariate regression modelling was used to analyze multiple variables (Aim 3). All demographic, PROMIS, and clinical information were treated as independent variables and assessed for their respective effects on postoperative PF, the dependent variable. Alpha level was set at 0.10 for inclusion of each variable in the regression model. Since PROMIS Depression was not normally distributed, the PROMIS Depression ordinal data by standard deviation increments was used in this multivariate analysis. The model fit was assessed r2 and standard error of the estimate. All analyses were completed using SPPS vs25.0.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

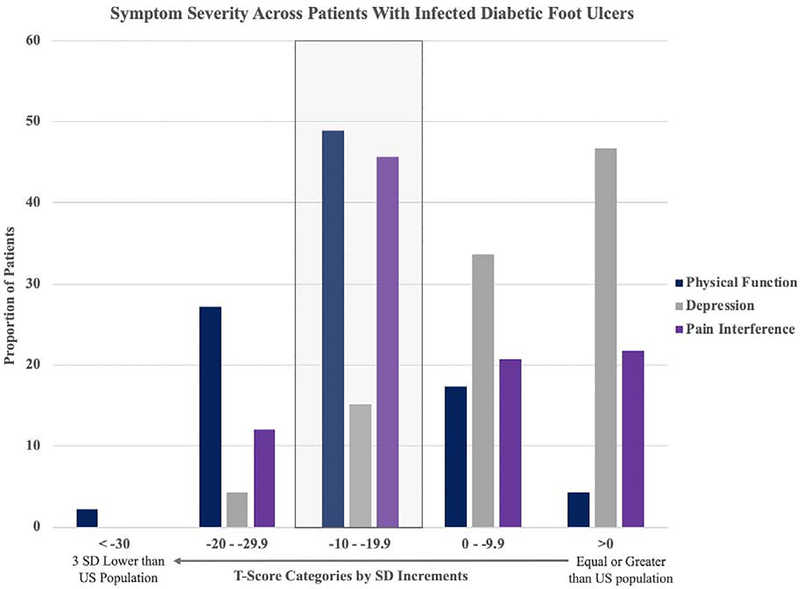

The mean age was 60.5 (33–96) years and mean follow-up 0077as 4.7 (3–12) months. The mean preoperative PF, PI, and depression changed from 34.4 ± 7.1 (range: 19.1–53.1), 58.7 ± 10.7 (range: 38.7–76.5), 51.4 ± 10.7 (range: 34.2–78.9) to postoperative 36.1 ± 8.8 (range: 14.7–63.8), 58.8 ± 10.0 (range: 38.6–83.8), 51.1 ± 11.6 (range: 34.2–79.9), respectively (ΔPF = 1.7, ΔPI=0.1, ΔD = −0.3; Table 1). Preoperative PF among DFU patients are markedly lower than the US population with 48.9% of patients (n=45) two standard deviations below average and 27.2% three standard deviations below the US average (Figure 2). The mean hemoglobin A1C (HgA1C) at initial visit was 8.1 ± 1.9 (range: 4.8–13.6) and the final follow-up mean A1C was 7.8 ± 1.9 (range: 4.8–13.1). A total of 23.9% (n=22) of patients were diagnosed with CRF. Half (n=46) of the patients underwent forefoot amputations, 15.2% (n=14) mid/hindfoot amputations, 13% (n=12) Syme or above amputations. At the end of the follow-up captured in this study, 68.5% (n=63) of the patients healed their DFU surgical wound (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Prognostic Factors | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Factors | ||

| Age (years) | 60.52 ± 11.5 | 33–96 |

| Gender (Male) | 74 (80.4%) | |

| BMI | 34.1 ± 6.9 | 22.0–57.5 |

| Symptom Severity (PROMIS T-Scores) | ||

| Preoperative | ||

| Physical Function | 34.4 ± 7.7 | 19.1–53.1 |

| Pain Interference | 58.7 ± 6 | 38.7–76.5 |

| Depression | 51.4 ± 10.7 | 34.2–78.9 |

| Postoperative | ||

| Physical Function | 36.1 ± 8.8 | 14.7–63.8 |

| Pain Interference | 58.5 ± 10.0 | 38.6–83.8 |

| Depression | 51.6 ± 11.6 | 34.2–79.9 |

| Clinical Factors | ||

| Preoperative A1C | 8.1 ± 1.9 | 4.8–13.6 |

| Postoperative A1C | 7.8 ± 1.9 | 4.8–13.1 |

| Chronic Renal Failure | 22 (23.9%) | |

| Clinical Outcome | ||

| Amputation Level | ||

| Forefoot Amputation | 46 (50.0%) | |

| Midfoot Amputation | 14 (15.2%) | |

| Syme/Above Amputation | 12 (13.0%) | |

| Healed (Yes) | 63 (68.5%) | |

| Length of Follow Up (months) | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 3–12 |

Figure 2. Baseline Symptom Severity Across Patients with Infected DFU.

Mean initial PROMIS PF, PI, D scores assessed by standard deviations (SDs) below US population average. High raw PI T-scores were transformed into SDs lower than US population. The boxed in category indicates two SD below US average.

Several methods are used for diagnosing PN, with Semmes-Weinstein 5.07 (10G) monofilament test being the most prevalent test among healthcare providers due to convenience and availability. One hundred and three patients out of 110 were noted to have PN. Of the 103, 48 were diagnosed with PN by the senior author who performed Semmes-Weinstein 5.07G monofilament test to diagnose PN. However, due to the lack of diagnostic standardization, we were not able to clearly confirm the validity of PN in the remaining 55 patients who were previously diagnosed with peripheral neuropathy by another physician (primary care, neurologist or endocrinologist). Nevertheless, they were all documented to have reduced sensation when 5.07G monofilament test was performed by the senior author.

Univariate Analyses

Univariate analyses, summarized in Table 2, were performed on each variable to evaluate association with postoperative PF scores. Spearman correlations confirmed preoperative PF (p < 0.01), PI (p < 0.01), and depression (p < 0.01) was correlated to postoperative PF (Table 2). Chi-square analysis showed an association of CRF (p < 0.02) and amputation level (p < 0.04) with postoperative PF. However, chi-square analysis of Age (p = 0.58), gender (p = 0.13), and BMI (p = 0.58) with postoperative PF scores were not significant. Preoperative A1C (p = 0.72), postoperative A1C (p = 0.10), and healing status (p = 0.17) did not show significant correlation with postoperative PF. Of note, the length of follow-up showed no significant correlation (p = 0.08). Preoperative PF showed the highest correlation (r = 0.43) among PROMIS scales.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis for Postoperative PF

| Postoperative Physical Function | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prognostic Factors | Univariate Rho* or Chi-Square& Values | p-values |

| Patient Factors | ||

| Age | −0.06* | 0.58* |

| Gender | 7.2& | 0.13& |

| BMI | −0.12* | 0.27* |

| Initial Symptom Severity (PROMIS Scores) | ||

| Physical Function | 0.43* | p <0.01* |

| Pain Interference | −0.36* | p <0.01* |

| Depression | −0.36* | p <0.01* |

| Clinical Factors | ||

| Preoperative A1C | 0.04* | 0.72* |

| Postoperative A1C | −0.19* | 0.10* |

| Chronic Renal Failure | 11.2& | 0.02& |

| Type of Amputation | 21.5& | 0.04& |

| Healing | 6.4& | 0.17& |

| Length of Follow Up | −0.19* | 0.08* |

Multivariate Regression Modelling

Multivariate regression modelling (r = 0.55; r2 = 0.30) revealed postoperative PF is predicted by initial PF (p = 0.004), amputation level (p = 0.008), and wound healing status (p = 0.001) (Table 3). The numerical equation for predicting postoperative PF outcome is:

Table 3.

Multivariate Postoperative PF Prediction Model

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 29.424 | 4.725 | 6.227 | 0 | |

| PFinitial Score | 0.338 | 0.113 | 0.294 | 2.984 | 0.004 | |

| Amputation Category | −2.633 | 0.962 | −0.275 | −2.736 | 0.008 | |

| Heal/Not Heal | −5.871 | 1.773 | −0.309 | −3.312 | 0.001 | |

| Dependent Variable: Postoperative PF Score | r = 0.55 | r2=0.30 | ||||

| PFpostoperative | ||||||

| = 29.42 + 0.34 (PFinitial) – 2.63(Amputation Category, 0 – 3) – 5.87 (Healed = 0, Not Heal = 1) | ||||||

The standard error of the estimate was ±7.0 t-score points. Judging by the r2 change, the model had greater prediction power than the best univariate association: preoperative PF (Δr = +0.12). Follow-up length did not add to the predictive power of the model.

DISCUSSION

Patient-Report Outcome (PRO) is a powerful tool that gives patients a voice in their healthcare and informs clinicians and policy makers of treatment efficacy on patients’ quality of life. PROMIS has been shown to be a highly adaptable and a well-validated person-centered PRO measure. It improves upon the accuracy of historical PRO outcome scores and supports standardization across studies. Though the efficacy of PROMIS as a predictor in foot and ankle surgeries has been evaluated, it has never been assessed specifically in the DFU population. This study shows that preoperative PROMIS scores is predictive, of postoperative PROMIS PF in DFU patients.

The study patient sample is representative of the DFU cohort from a single surgeon of an academic practice. All patients underwent procedural interventions for their infected DFU with a mean follow-up of 4.7 months (Table 1). The primary purpose of this study was to accurately assess the baseline physical function of DFU patients and investigate various factors that affect their post-operative physical function. Therefore, the study follow-up period was set relatively short to focus our investigation on those who did not require additional surgical procedure within 3 months from the index surgery. Despite a majority of patients receiving various degrees of amputation and 13% receiving Syme or limb amputations, 68.5% (n=63) of the patients eventually healed their foot ulcer or surgical wound. In general, the healing rate and limb amputation proportion of infected DFU agrees with previous reports44,45. Overall, DFU patients showed baseline poor PF and high PI. The average PF T-score of DFU patients was 2 standard deviations below US population average and surgical interventions did not significantly improve or deteriorated patients’ PF. PI was also commonly observed to be worse than the average US population (Figure 2). This outcome appears consistent with studies of that show poor generic health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as well as disease specific HRQoL36,46,47 in patients with diabetes. The above information suggests that most infected DFU patients presents with baseline low PF and high pain levels, which are unlikely to change significantly after an uneventful healing of recommended amputation procedure.

Interestingly the univariate analyses showed that demographic factors and most clinical factors were not significantly correlated with postoperative PF scores (Table 2). In previous studies where male gender was a significant risk factor for DFU and poorer outcome, gender became insignificant when controlled for PN48,49. This concurs with the findings of this study, as we assumed PN as a shared comorbidity among the included patients. Statistically significant variables for predicting postoperative PF were preoperative PROMIS domain scores (PF, PI, Depression), amputation level, and CRF. The significant PROMIS p-values further supports the validity of PROMIS as an accurate indicator of patients’ health status. Moreover, the impact of CRF status and amputation level on postoperative PF may be directly attributed by disease progression of diabetes.

Through multivariate modelling, we formulated a numerical equation for postoperative PF prediction using preoperative PF T-scores, amputation level, and healing status (Table 3). The equation indicates that with each increase in amputation level, the postoperative PF T-score decreases by 2.63. This concurs with previous findings that showed speed and cadence decreased while oxygen consumption per meter walked and the ratio of cardiac function to oxygen consumption both increased with more proximal amputations50. It is interesting to note that although wound healing status alone did not significantly correlate, when combined with other variables, its correlation with postoperative PF was significant. Healing status of DFU moderates 5.87 points postoperatively making it the most impactful coefficient of the equation. Patients who do not heal their ulcer results in a drop of almost one standard deviation in their postoperative PF score. Higher initial PF can moderate the reduction of PF due to amputation level and/or healing outcome which may provide an opportunity for pre-rehabilitation to improve preoperative PF as a potential modifiable factor with treatment. The authors do not recommend extending the utilization of the suggested numeric equation for suggesting an amputation level, which should be determined by a surgeon based on various clinical factors, such as extent of infection, skin and soft tissue viability, circulation, and other medical comorbidities. The purpose of the numeric equation is to aid patients’ understanding of expected changes in PF, to suggest modifiable risk factors (i.e. maximizing preoperative PF, glucose control to optimize wound healing potential), and to facilitate preoperative counseling.

It is worth mentioning that despite CRF acting as a significant univariate, it does not add to the multivariate model. When clustered, healing status outcompetes CRF as a variable. Therefore, CRF is likely a redundant variate with healing status, which was not a significant univariate but contributes meaningfully to the regression model. The multivariate regression modelling yielded a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.55 and a coefficient of determination (r2) of 0.30. That is, the included variables show a positive correlation with postoperative PF, and accounts for 30% of postoperative PF variance.

The low r2 of the predictive equation suggests this model may be used to assist in setting patient expectations. For example, a patient who scores mean PF, PI, and Depression preoperatively and undergoes a forefoot amputation to heal their DFU would be estimated to achieve a postoperative PF of 38.5 ±7.0. In other words, the patient’s postoperative PF likely lie between 25.5 to 45.5 in 68% of the time. This initial predictive model suggests that patient symptoms (i.e. PROMIS scales) when combined with clinical variables may improve clinical decision-making of the patient’s treatment plan as well as aid in fostering patient-centered communication style to set realistic expectations and in turn reduce expectancy effect51.

There are several limitations to this study including heterogeneity within the DFU cohort. Included patients have varying comorbidities uncaptured by this study that may confound the statistical associations in the study. The study also did not control for race or ethnicity, which limits overall generalizability of the results. Despite identifying 240 participants initially, only 92 were included in the analysis. Due to the complexity of DFU patients who often develop recurrent wound or infections that necessitate further surgery, having a longer follow-up would significantly reduce patient who met the inclusion criteria. Nevertheless, the study provides a general expectation for the average PF at 4–5 months after surgery and is the first to elucidate the baseline PF in the DFU population. The correlation coefficient of the multivariate regression model indicates that there are other clinical and social factors unaccounted for within the regression model. Factors such as socio-economic status (SES), smoking status, level of self-efficacy, perceived health locus of control, anxiety, stress, and catastrophization have all previously been indicated to affect treatment adherence and health outcomes36,48,52,53. These factors may improve upon the current regression model and should be considered in future studies.

In conclusion, DFU patients have baseline PF averaging two standard deviations below the US average and unlikely to change significantly after surgical intervention. Preoperative PROMIS scores are predictive of postoperative PROMIS outcome in DFU patients. Postoperative PF score can be predicted by preoperative PROMIS PF in conjunction with amputation level and healing status. The predictive algorithm can serve to set expectations and further provide domain-specific information for clinicians and infected DFU patients to facilitate preoperative counseling and consenting process. The persistent low physical function scores in patient brings attention to the need for multidisciplinary collaboration and/or referral to mental health professionals to assist in post-amputation transitions.

Highlights.

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) data reveal diabetic foot ulcer patients’ physical function averaging two standard deviations below the U.S. average.

Our findings indicate that surgical interventions do not necessarily improve physical function in diabetic foot ulcer population.

We introduce a predictive model to estimate post-operative physical function.

This proposed equation can aid in patients understanding of expected post-operative physical function and modifiable factors to optimize functional outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH, NIAMS (R21AR074571).

Declaration-of-competing-interests

Dr. Baumhauer reports grants from NIH during the conduct of the study; personal fees from CORR, personal fees from Best Doctors, personal fees from Cartiva Medical, personal fees from DJO, personal fees from Ferring Pharma, personal fees from Nextremity Solutions, personal fees from Stryker, personal fees from Wright Medical, other from Trimed, other from PROMIS Health Organization, outside the submitted work. Dr. Oh reports grants from NIH during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Innomed, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). National Institute on Aging; https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/resource/patient-reported-outcomes-measurement-information-system-promis Accessed January 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fries JF, Witter J, Rose M, Cella D, Khanna D, Morgan-DeWitt E. Item response theory, computerized adaptive testing, and PROMIS: assessment of physical function. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(1):153–158. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodke DJ, Saltzman CL, Brodke DS. PROMIS for Orthopaedic Outcomes Measurement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(11):744–749. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevans M, Ross A, Cella D. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Efficient, standardized tools to measure self-reported health and quality of life. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(5):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson MR, Houck JR, Saltzman CL, et al. Validation and Generalizability of Preoperative PROMIS Scores to Predict Postoperative Success in Foot and Ankle Patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(7):763–770. doi: 10.1177/1071100718765225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacalao EJ, Greene GJ, Beaumont JL, et al. Standardizing and personalizing the treat to target (T2T) approach for rheumatoid arthritis using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): baseline findings on patient-centered treatment priorities. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(8):1729–1736. doi: 10.1007/s100e7-017-3731-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makhni EC, Meadows M, Hamamoto JT, Higgins JD, Romeo AA, Verma NN. Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) in the upper extremity: the future of outcomes reporting? J Shoulder Elbow. Surg. 2U7;26(2):352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beleckas CM, Padovano A, Guattery J, Chamberlain AM, Keener JD, Calfee RP. Performance of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Upper Extremity (UE) Versus Physical Function (PF) Computer Adaptive Tests (CATs) in Upper Extremity Clinics. J Hand Surg. 2017;42(11):867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boody BS, Bhatt S, Mazmudar AS, Hsu WK, Rothrock NE, Patel AA. Validation of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) computerized adaptive tests in cervical spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28(3):268–279. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.SPINE17661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tishelman JC, Vasquez-Montes D, Jevotovsky DS, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System instruments: outperforming traditional quality of life measures in patients with back and neck pain. J Neurosurg Spine. February 2019:1–6. doi: 10.3171/2018.10.SPINE18571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez JL, Mosher ZA, Watson SL, et al. Readability of Orthopaedic Patient-reported Outcome Measures: Is There a Fundamental Failure to Communicate? Clin Orthop. 2017;475(8):1936–1947. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5339-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung M, Baumhauer JF, Brodsky JW, et al. Psychometric Comparison of the PROMIS Physical Function CAT With the FAAM and FFI for Measuring Patient-Reported Outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(6):592–599. doi: 10.1177/1071100714528492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung M, Nickisch F, Beals TC, Greene T, Clegg DO, Saltzman CL. New paradigm for patient-reported outcomes assessment in foot & ankle research: computerized adaptive testing. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(8):621–626. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung M, Baumhauer JF, Latt LD, et al. Validation of PROMIS ® Physical Function computerized adaptive tests for orthopaedic foot and ankle outcome research. Clin Orthop. 2013;471(11):3466–3474. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3097-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Askew RL, Cook KF, Revicki DA, Cella D, Amtmann D. Clinical Validity of PROMIS® Pain Interference and Pain Behavior in Diverse Clinical Populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung M, Franklin JD, Hon SD, Cheng C, Conrad J, Saltzman CL. Time for a paradigm shift with computerized adaptive testing of general physical function outcomes measurements. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(1):1–7. doi: 10.1177/1071100713507905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papuga MO, Mesfin A, Molinari R, Rubery PT. Correlation of PROMIS Physical Function and Pain CAT Instruments With Oswestry Disability Index and Neck Disability Index in Spine Patients. Spine. 2016;41(14):1153–1159. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, Cella D. Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(2):513–527. doi: 10.1037/a0035768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nixon DC, McCormick JJ, Johnson JE, Klein SE. PROMIS Pain Interference and Physical Function Scores Correlate With the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM) in Patients With Hallux Valgus. Clin Orthop. 2017;475(11):2775–2780. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5476-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernstein DN, Kelly M, Houck JR, et al. PROMIS Pain Interference Is Superior vs Numeric Pain Rating Scale for Pain Assessment in Foot and Ankle Patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40(2):139–144. doi: 10.1177/1071100718803314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho B, Houck JR, Flemister AS, et al. Preoperative PROMIS Scores Predict Postoperative Success in Foot and Ankle Patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(9):911–918. doi: 10.1177/1071100716665113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen RE, Papuga MO, Voloshin I, et al. Preoperative PROMIS Scores Predict Postoperative Outcomes After Primary ACL Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(5):2325967118771286. doi: 10.1177/2325967118771286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berliner JL, Brodke DJ, Chan V, SooHoo NF, Bozic KJ. Charnley John Award: Preoperative Patient-reported Outcome Measures Predict Clinically Meaningful Improvement in Function After THA. Clin Orthop. 2016;474(2):321–329. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4350-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein DN, Houck JR, Gonzalez RM, et al. Preoperative PROMIS Scores Predict Postoperative PROMIS Score Improvement for Patients Undergoing Hand Surgery. Hand N Y N August 2018:1558944718791188. doi: 10.1177/1558944718791188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen RE, Papuga MO, Nicandri GT, Miller RJ, Voloshin I. Preoperative Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scores predict postoperative outcome in total shoulder arthroplasty patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. November 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubery PT, Houck J, Mesfin A, Molinari R, Papuga MO. Preoperative PROMIS Scores Assist in Predicting Early Postoperative Success in Lumbar Discectomy. Spine. August 2018. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margolis DJ, Malay DS, Hoffstad OJ, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, diabetic foot ulcer, and lower extremity amputation among Medicare beneficiaries, 2006 to 2008: Data Points #1 In: Data Points Publication Series. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63602/ Accessed February 15, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiber G Epidemiology of foot ulcers and amputations in the diabetic foot In: Levin and O’Neal’s The Diabetic Foot. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malgrange D, Richard JL, Leymarie F, French Working Group On The Diabetic Foot. Screening diabetic patients at risk for foot ulceration. A multi-centre hospital-based study in France. Diabetes Metab. 2003;29(3):261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atreja A, Kalra S. Infections in diabetes. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(9):1028–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis †. Ann Med. 2017;49(2):106–116. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2016.1231932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jelinek HF, Osman WM, Khandoker AH, et al. Clinical profiles, comorbidities and complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients from United Arab Emirates. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1). doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sekhar MS, Thomas RR, Unnikrishnan MK, Vijayanarayana K, Rodrigues GS. Impact of diabetic foot ulcer on health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Semin Vasc Surg. 2015;28(3–4):165–171. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meijer JWG Trip WHEJ, Jaegers SMHJ, Links TP, Smits AJ, Groothoff JW. Quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(8):336–340. doi: 10.1080/09638280010005585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Mayer D, et al. Diabetic foot ulcers: Part I. Pathophysiology and prevention. J. Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(1):1.e1–18; quiz 19–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J, et al. High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study. Diabetologia. 2007;50(1):18–25. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0491-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, Smith AL, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(6):521–534. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70065-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai J-S, Cella D, Choi S, et al. How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: a PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10 Suppl):S20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rose M, Bjorner JB, Gandek B, Bruce B, Fries JF, Ware JE. The PROMIS Physical Function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(5):516–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150(1):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katsilambros N, ed. Atlas of the Diabetic Foot. 2 ed. Chichester, West Sussex Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexiadou K, Doupis J. Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Ther. 2012;3(1). doi: 10.1007/s13300-012-0004-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redekop WK, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk RP, Rutten GEHM, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Niessen LW. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Dutch patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thommasen HV, Zhang W. Health-related quality of life and type 2 diabetes: A study of people living in the Bella Coola Valley. BCMJ. 2016;48(6) 272–278. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nongmaithem M, Bawa APS, Pithwa AK, Bhatia SK, Singh G, Gooptu S. A study of risk factors and foot care behavior among diabetics. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2016;5(2):399–403. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dinh T, Veves A. The influence of gender as a risk factor in diabetic foot ulceration. Wounds Compend Clin Res Pract. 2008;20(5):27–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinzur MS, Gold J, Schwartz D, Gross N. Energy Demands for Walking in Dysvascular Amputees as Related to the Level of Amputation. Orthop Thorofare. 1992; 15(9):1033–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenthal R Interpersonal Expectancy Effects: A 30-Year Perspective. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1994;3(6):176–179. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drake C, Mallows A, Littlewood C. Psychosocial variables and presence, severity and prognosis of plantar heel pain: A systematic review of cross-sectional and prognostic associations. Musculoskeletal Care. 2018;16(3):329–338. doi: 10.1002/msc.1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Náfrádi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PloS One. 2017;12(10):e0186458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]