Abstract

Effective suicide prevention is hindered by a limited understanding of the natural progression and neurobiology of the suicidal process. Our objective was to characterize the duration of the suicidal process and its relation to possible determinants: time judgment and cognitive impulsivity. In four groups of adults of both sexes including recent suicide attempters (n=57), suicidal ideators (n=131), non-suicidal depressed controls (n=51) and healthy controls (n=48) we examined time estimation and production, impulsivity and other cognitive variables. Duration of the suicidal process was recorded in suicide attempters. The suicide process duration, suicide contemplation and action intervals, had a bimodal distribution, ~40% of attempters took less than 5 minutes from decision to attempt. Time slowing correlated negatively with the suicidal action interval (time from the decision to kill oneself to suicide attempt) (p=.003). Individuals with suicide contemplation interval shorter than three hours showed increased time slowing, measured as shorter time production at 35 seconds (p=.011) and 43 seconds (p=.036). Delay discounting for rewards correlated with time estimation at 25 minutes (p=0.02) and 90 seconds (p=.01). Time slowing correlated positively with suicidal ideation severity, independently of depression severity (p<.001). Perception of time slowing may influence both the intensity and the duration of the suicidal process. Time slowing may initially be triggered by intense psychological pain, then worsen the perception of inescapability in suicidal patients.

Keywords: suicide, time perception, depression, impulsivity, suicidal process

1. Introduction

Despite decades of research, suicide rates continue to increase. Effective suicide prevention is hindered by a limited understanding of the neurobiology and natural history of the suicidal process. The duration of the suicidal process has been characterized in lifetime terms (Neeleman et al., 2004; Runeson et al., 2010) or in function of the immediate pre-attempt phase, encompassing the most recent suicidal crisis (Deisenhammer et al., 2009; Kattimani et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2002; Wasserman et al., 2008). The length of the suicidal process, and thus the time available for intervention, has a major impact on suicide prevention. Thus, understanding of the suicidal process and associated factors is key. We focused on two elements of the pre-suicide attempt phase: suicide contemplation and suicidal action intervals (Klonsky et al., 2017; Neeleman et al., 2004). By suicide contemplation interval we refer to the time from onset of suicidal ideation to decision to kill oneself. We defined suicidal action interval as the time between the decision to kill oneself and a suicide attempt.

Impulsive suicide attempts can be defined in function of the generation of a plan or by the duration of the suicidal process, e.g. from the onset of suicidal ideation until suicidal behavior and death. Several factors are considered when assessing the level of planning of suicidal behavior, such as the timing of preparations, isolation from others, presence of help-seeking behavior or suicide notes (Anestis et al., 2014). Because of our interest in the mechanisms leading to acute suicidal behavior, we focused on the duration of the immediate pre-attempt phase of the suicidal process. The duration of the suicidal process can be influenced by how and individual processes or judges time, impulsivity, as well as other cognitive factors (Neeleman et al., 2004).

Time judgment is the objective capacity of an individual to judge the length of a given span of time, and can be examined by the complementary time estimation or time production tasks, in which the participant is asked to estimate the length of a given time interval or to produce a time span of a certain duration (Bschor et al., 2004). The experience of time dilation or slower time flow in time judgement tasks has been described in depressed patients (Bschor et al., 2004). However, the limited examination of the experience of time in suicidal patients has shown an impaired ability to concretely imagine the future in suicide attempters (Williams et al., 1996).

Abnormal time judgment in suicidal individuals may be related to elevated cognitive impulsivity (Liu et al., 2017) and other cognitive impairments (Richard-Devantoy et al., 2014). The experience of overwhelming psychological pain in conjunction with distorted time processing could worsen suicidal thoughts (suicidal ideation severity) and lead to impulsive self-harm. For instance, abnormal perception of time may influence the subjective cost of waiting, triggering cognitive impulsivity.

In order to further understand the suicidal process, we examined the duration of the suicidal process in relation to time judgment, cognitive variables and suicidal ideation severity across the suicide risk spectrum (i.e. recent suicide attempters, current suicidal ideators, non-suicidal depressed patients and healthy controls). We hypothesized that: a) the duration of the suicidal process will be negatively correlated with time slowing and cognitive impulsivity; b) impulsive suicide attempters will show increased time slowing; c) time slowing will positively correlate with cognitive impulsivity; and d) time slowing will positively correlate with suicidal ideation severity.

2. Experimental Procedures

Participants

Four groups of adults of both genders, ages 18–65 years, were recruited between January 2015 and July 2017.

Recent suicide attempters (Attempters; N=57): currently depressed patients with a recent (within the previous five days) suicide attempt as defined by a score of ≥ 2 in the actual lethality/medical damage subscale and a score of ≥ 1 in the potential lethality subscale of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner et al., 2011) (81 contacted and 57 met inclusion/exclusion criteria and agreed to participate);

Current Suicidal Ideators (Ideators; N=131): currently depressed patients with current suicidal ideation, defined by score ≥ 1 in the C-SSRS Suicidal Ideation Severity subscale -currently, not lifetime- and no suicidal behavior in the previous six months (165 contacted and 131 met inclusion/exclusion criteria and agreed to participate);

Non-Suicidal Depressed Patients (N=51): currently depressed patients with no suicidal ideation or behavior in the previous six months (all met inclusion/exclusion criteria); and

Healthy Controls (N=48): participants without a history of mental illness or drug abuse. Participants were recruited from the psychiatric inpatient units of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Psychiatric Research Institute (PRI) (Attempters, Ideators and non-suicidal depressed patients), the psychiatric outpatient clinics of the UAMS PRI (non-suicidal depressed patients) and the local community non-suicidal depressed patients and healthy controls. All depressed patients fulfilled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5 criteria for major depressive episode. Exclusion criteria were: a) inability to speak, read and write English; b) inability to provide informed consent; c) involuntary hospitalization; d) history of dementia, neurovascular, or neurodegenerative conditions; e) history of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or unspecified psychosis; f) physical disabilities that prohibit task performance, such as blindness or deafness; and g) current intoxication or undergoing alcohol, benzodiazepine, opioid or barbiturate withdrawal. UAMS Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. The study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were compensated for their participation in the study.

Our study focused on acute suicidal behavior as a state, not a trait. Thus, recent suicidal behavior was an exclusion criterion for the Suicidal Ideation and Non-Suicidal Depressed groups and suicidal ideation within the previous six months was an exclusion criterion for the Non-Suicidal Depressed group. Our group and others have previously used this empirical six month cut-off for remote suicidal behavior in order to identify cognitive and physiological changes associated with recent suicidal behavior (Cáceda et al., 2014; Caceda et al., 2017; Carbajal et al., 2017; Gibbs et al., 2016; van Heeringen et al., 2017). There were individuals with a lifetime history of suicide attempts in the three depression groups. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of depressed patients after a recent suicide attempt (Attempters), depressed patients with suicidal ideation (Ideators), non-suicidal depressed patients and healthy subjects.

| Attempters | Ideators | Depressed non-suicidal | Healthy controls | Adjusted p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 57 | 131 | 51 | 48 | |

| Age | 33.1±10.4 | 39.3±11.7 | 34.8±11.9 | 36.1±9.5 | .08 |

| Gender (f) | 37 (65%) | 80 (61%) | 30 (59%) | 33 (69%) | .755* |

| Race | .48* | ||||

| White | 35 (61%) | 58 (45%) | 28 (55%) | 25 (52%) | |

| Black | 17 (30%) | 66 (50%) | 21 (41%) | 20 (42%) | |

| Other | 5 (9%) | 7 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) | |

| Marital status | .25* | ||||

| Never married | 22 (39%) | 50 (38%) | 12 (24%) | 38 (79%) | |

| Married | 12 (21%) | 24 (18%) | 18 (35%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Divorced/ widowed | 23 (40%) | 57 (44%) | 21 (41%) | 10 (21%) | |

| Education (years) | 12.6±1.9d | 13.2±2.4d | 14.1±3.1d | 16.6±1.9a,b,c | <.001 |

| Functioning level | |||||

| Student or working/unemployed, disabled or retired | 21 (37%) / 36 (63%) | 38 (29%) / 93 (71%) | 18 (35%) / 33 (65%) | 30 (63%)/18 (37%) | <.001* |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Inpatient | 57 (100%) | 131 (100%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | <.001 |

| Major Depressive | 31 (54%) | 67 (51%) | 26 (51%) | 0 (0%) | <.001 |

| Disorder | |||||

| Bipolar disorder | 11 (19%) | 41 (31%) | 13 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Depression not otherwise specified | 14 (26%) | 23 (18%) | 12 (24%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Depression (BDI) | 36.8±12.8c,d | 40.7±9.8c,d | 25.9±13.1a,b,d | 3.9±4.3a,b,c | <.001 |

| Presence of anxiety disorder | 15 (26%) | 33 (25%) | 10 (20%) | 0 (0%) | <.001 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | 28.6±14.4d | 32.0±13.1d | 26.7±14.1d | 7.3±9.1a,b,c | <.001 |

| Hopelessness (BHS) | 9.7±2.4b,d | 10.8±2.3a,c,d | 9.3±2.6b | 8.2±1.0a,b | <.001 |

| Individuals on antidepressant medications | 37 (65%) | 85 (65%) | 21 (41%) | 0 (0%) | .0111* |

| Presence of substance use disorder (except tobacco) | 42 (74%) | 87 (66%) | 31 (61%) | 0 (0%) | <.001* |

| Current smoking | 31 (54%) | 71 (54%) | 24 (57%) | 3 (6%) | .174* |

| Suicide related measures | |||||

| Presence of suicidal ideation | 34 (60%) | 131 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | <.001* |

| Suicidal ideation severity (C-SSRS) | 1.4±1.6b,c,d | 2.6±1.5a,c,d | 0.0±0.0a,b | 0.0±0.0a,b | <.0011 |

| Presence of lifetime suicide attempts | 57 (100%) | 94 (72%) | 15 (19%) | 0 (0%) | <.0011 |

| Number of lifetime suicide attempts | 4.4±5.4d | 4.0±11.1c,d | 0.4±0.8b | 0.0±0.0a,b | <.0011 |

| Pressure pain threshold | 14.7±5.1b,d | 12.9±4.9a,c,d | 12.8±4.3a,d | 8.2±1.9a,b,c | <.001 |

| Current physical pain | 3.6±3.1b,d | 4.8±3.3a,c,d | 2.7±2.6b,d | 0.7±1.5a,b | <.001 |

| Current psychological pain | 5.7±3.7c,d | 7.6±2.3c,d | 4.7±2.6a,b,d | 0.3±0.9a,b,c | <.001 |

Mean ± standard deviation

ANOVA was performed for all demographic variables.

Yates chi-square Post-hoc analysis were performed with Tukey’s test and shows:

compared to Attempters group;

compared to Ideators group;

compared to depressed non-suicidal group;

compared to healthy control group;

Chi-square between Attempters, Ideators and depressed non-suicidal groups

Procedures

Screening.

Each morning, all newly consecutively admitted patients to the psychiatric inpatient units who met eligibility criteria were given information about the study, and asked for permission to be contacted about the study. One of the investigators provided information to potential participants. If they were agreeable, written informed consent was obtained. For non-suicidal depressed patients and healthy controls, interested individuals underwent telephone screening and then were scheduled for informed consent and study assessments.

Evaluation.

After written informed consent, participants were interviewed to obtain demographic data, psychiatric and medical history, and cognitive and behavioral ratings. Psychiatric diagnostic assessments, as defined by the DSM-5, were performed as part of the admission interview by or directly under the supervision of a board-certified psychiatrist. All patients (attempters, ideators and non-suicidal depressed) were undergoing a major depressive episode; none was undergoing a mixed or manic episode. The primary diagnosis included: major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or depression not otherwise specified. The presence of any anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia and panic disorder), current substance use disorder other than tobacco and current antidepressant treatment was documented. Lastly, for the Attempter group, the time since the suicide attempt, the suicide contemplation interval (time from onset of suicidal ideation to decision to kill oneself), and the suicidal action interval (time from decision to kill oneself to suicide attempt) were established in a semi-structured interview. See Electronic Supplementary Material. Based on previous data regarding the onset of premeditation of a suicide attempt we set a three-hour cut-off time to differentiate impulsive and non-impulsive suicide attempts (Bagge et al., 2013).

Measures

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) (Beck et al., 1996), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck and Steer, 1990) and Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (Beck, 1988) were administered. The C-SSRS was used to characterize self-harm thoughts and actions (Posner et al., 2011).

The C-SSRS, a widely used interviewer-rated instrument with different subscales to quantify current and past history of self-harm thoughts and actions (Posner et al., 2011), was administered by RC or two research assistants who were trained and certified (http://cssrs.columbia.edu/training/training-research-setting/).

The BDI-II is a 21 item self-report instrument to measure severity of depression (Beck et al., 1996).

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21 item self-report instrument to measure severity of anxiety (Beck and Steer, 1990).

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) is a 20 item self-report instrument to assess the level of positive and negative beliefs about the future (Beck, 1988).

Cognitive impulsivity for gains and losses was evaluated with the Monetary Choice Questionnaire, which presents 27 choices between immediate smaller gains/losses and delayed larger ones (Kirby et al., 1999). We used proportional scoring for responses, based on the calculation of proportions of the delayed outcome (number of choices of a delayed gain or loss divided by the number of questions) separately for the small, medium and large amounts. Reliability analyses have shown that response proportions and individual estimates of discounting rates are so highly correlated that they could be assumed to be interchangeable (Myerson et al., 2014). Both the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) and delay discounting task calculate delay discounting in function of the generation of an individual’s discounting rates.

We slightly modified the protocol described by Bschor and colleagues for Time Estimation and Production Tasks (Bschor et al., 2004) by including a longer (25 minute) interval that may show a more daily life or clinical relevance. First, participants underwent training consisting of two time estimation (4 and 8 seconds) and two time production (3 and 10 seconds) trials. In the Time Estimation Task participants were asked to estimate for how long different geometric figures were presented to them (7, 34 and 90 seconds) on a personal computer. In the Time Production Task, participants were asked to stop the presentation of different geometric figures after four different time intervals (8, 35, 43 and 109 seconds) by clicking a mouse button. The order of the stimuli was counterbalanced. For both tasks participants were not distracted, nor were they instructed not to count internally. In time overestimation or slowing, time spans are judged longer than they are: in time estimation tasks an interval is estimated longer, but in time production tasks shorter time spans than demanded are produced. In time underestimation or speeding, the opposite occurs (Bschor et al., 2004). Both tasks were programmed in E-prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh). Both scripts are available upon request. Following informed consent, an investigator set a timer for 25 minutes and proceeded to start the interview of the participant. At the end of this period participants were asked to estimate how much time passed since they signed the informed consent form.

Visual attention and task switching were measured with the Trail Making Test (TMT) A and B (Reitan and Wolfson, 1985) and verbal fluency (naming animal and boy names in 60 seconds) (Newcombe, 1969) were used to examine executive function. We performed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11), which measures three subtypes of impulsivity: attentional/cognitive, motor and non-planning (Patton et al., 1995). Self-reported states of physical and psychological pain were measured with the Physical and Psychological Pain Scale (Olie et al., 2010), validated for depressed patients (Jollant et al., 2019).

Data analysis

To test whether the duration of the suicidal process is negatively correlated with time slowing and cognitive impulsivity, ordinal regression analyses were carried for suicide contemplation and suicidal action intervals as dependent variables. Independent variables were measures of time estimation and production, delayed discounting for gains and losses, age, sex, depression severity, suicidal ideation severity, number of lifetime suicide attempts, psychological pain, physical pain, verbal fluency, TMT-A and TMT-B. Only sex, study group, depression, anxiety, current physical and psychological pain severity, time estimation of 90 s and time production of 8 s were significant and included as covariates in a generalized linear model.

To test whether impulsive suicide attempters will show elevated time dilation, we used a two-tailed t-student test between impulsive and non-impulsive suicide attempts, using a three-hour cut-off time based on differential clinical presentation as shown by Bagge and collaborators (Bagge et al., 2013), to compare time estimation and production, age, sex, depression, anxiety, hopelessness, delay discounting and BIS-11 domains.

To examine the association between time judgement and cognitive impulsivity, stepwise linear regression analyses were carried with cognitive impulsivity as dependent variable (small, medium and large rewards and losses). Independent variables were time estimation (7s, 35s, 90s and 25 min) and production measures (8s, 35s, 43s and 109s), age, depression severity, verbal fluency and TMT-A and TMT-B scores.

To examine the association between time judgement and suicidal ideation, we used a repeated measures general linear model with suicidal ideation severity as dependent variable, time estimation (4 levels: 7s, 35s, 90s and 25 min) as independent variables, and age and depression severity as covariates. We then repeated the analysis in which the independent variables were time production measures (4 levels: 8s, 35s, 43s and 109s).

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All the tests were two-tailed and the significance level was set at p<0.05. We performed multiple comparison corrections using the false-discovery rate (FDR) method. An adjusted p-value is defined as the smallest significance level for which the given hypothesis would be rejected when the entire family of tests is considered. We reported adjusted p values.

3. Results

All our patients met the criteria for a major depressive episode. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics, while Table 2 shows the time judgment and cognitive measures of our study sample. Briefly, the majority of the sample were single young white women. Clinically, both Attempters and Ideators showed more severe depression (F(3,287)=154.22; p<.001), anxiety (F(3,287)=43.54; p<.001) and hopelessness (F(3,287)=18.259; p<.001) than the non-suicidal depressed patients, who in turn had higher scores than healthy controls.

Table 2.

Time judgment measures and cognitive in depressed patients after a recent suicide attempt (Attempters), depressed patients with suicidal ideation (Ideators), non-suicidal depressed patients and healthy subjects.

| Attempters | Ideators | Non-Suicidal Depressed | Healthy Controls | Adjusted p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 57 | 131 | 51 | 48 | |

| Time Processing | |||||

| Time Estimation | |||||

| 7 seconds | 8.2±3.0 | 8.4±3.9 | 7.9±1.7 | 7.0±1.3 | .068 |

| 34 seconds | 38.5±13.4 | 38.8±33.5 | 37.8±36.9 | 30.5±6.7 | .118 |

| 90 seconds | 88.2±37.4b | 108.1±79.7a,d | 101.6±41.0d | 73.3±16.9b,c | .005 |

| 25 minutes | 20.8±8.4 | 23.4±9.6 | 23.3±12.7 | .238 | |

| Time Production | |||||

| 8 seconds | 9.6±13.4 | 8.3±6.3 | 8.1±2.4 | 9.2±1.9 | .658 |

| 35 seconds | 32.4±11.0d | 31.2±13.3d | 34.1±9.1d | 39.3±7.4a,b,c | .001 |

| 43 seconds | 39.5±13.2d | 37.5±16.6d | 41.9±12.7d | 50.8±12.1a,b,c | <.001 |

| 109 seconds | 88.7±41.8d | 84.8±46.7d | 94.3±38.8d | 122.8±39.4a,b,c | <.001 |

| Cognitive measures | |||||

| Animal in 60 seconds | 19.6±5.0 | 19.7±6.0 | 20.3±5.7 | 20.7±6.5 | .803 |

| Boy names in 60 seconds | 18.4±5.5d | 18.9±5.3d | 20.9±4.6 | 20.8±4.7 | .043 |

| Trail Making A (seconds) | 30.1±12.7d | 32.5±13.3d | 28.6±10.6d | 18.7±5.0a,b,c | <.001 |

| Trail Making B (seconds) | 74.5±28.3d | 81.5±33.0d | 70.7±27.5d | 36.4±10.7a,b,c | <.001 |

| Monetary Choice Questionnaire, proportion of delayed choices | |||||

| Gains for small amounts | 6.3±2.2 | 6.6±1.8 | 6.8±1.7 | 7.2±2.1 | .186 |

| Gains for medium amounts | 5.7±2.2b,c,d | 6.4±1.9a,d | 6.6±0.4a,d | 7.7±2.1a,b,c | <.001 |

| Gains for large amounts | 5.4±2.3d | 6.0±2.1d | 6.0±0.4d | 7.7±1.9a,b,c | <.001 |

| Losses for small amounts | 5.5±2.8c,d | 5.0±3.0d | 4.3±0.4a,d | 7.2±2.1a,b,c | <.001 |

| Losses for medium amounts | 5.3±2.9d | 5.0±3.0d | 4.6±0.4d | 7.7±2.1a,b,c | <.001 |

| Losses for large amounts | 5.6±2.7d | 5.1±3.1d | 4.9±0.4d | 7.7±1.9a,b,c | <.001 |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale | |||||

| Attentional | 19.4±5.4d | 19.9±4.7d | 18.6±4.3d | 15.2±3.8a,b,c | <.001 |

| Motor | 25.2±6.3d | 26.0±5.8d | 24.6±4.7d | 19.9±2.4a,b,c | <.001 |

| Non-Planning | 27.7±7.0d | 29.3±5.5d | 26.6±3.2d | 20.1±3.6a,b,c | <.001 |

Mean ± standard deviation

ANOVA was performed for all demographic variables.

Post-hoc analysis were performed with Tukey’s test and shows:

compared to Attempters group;

compared to Ideators group;

compared to depressed non-suicidal group;

compared to healthy control group;

Suicidal process duration

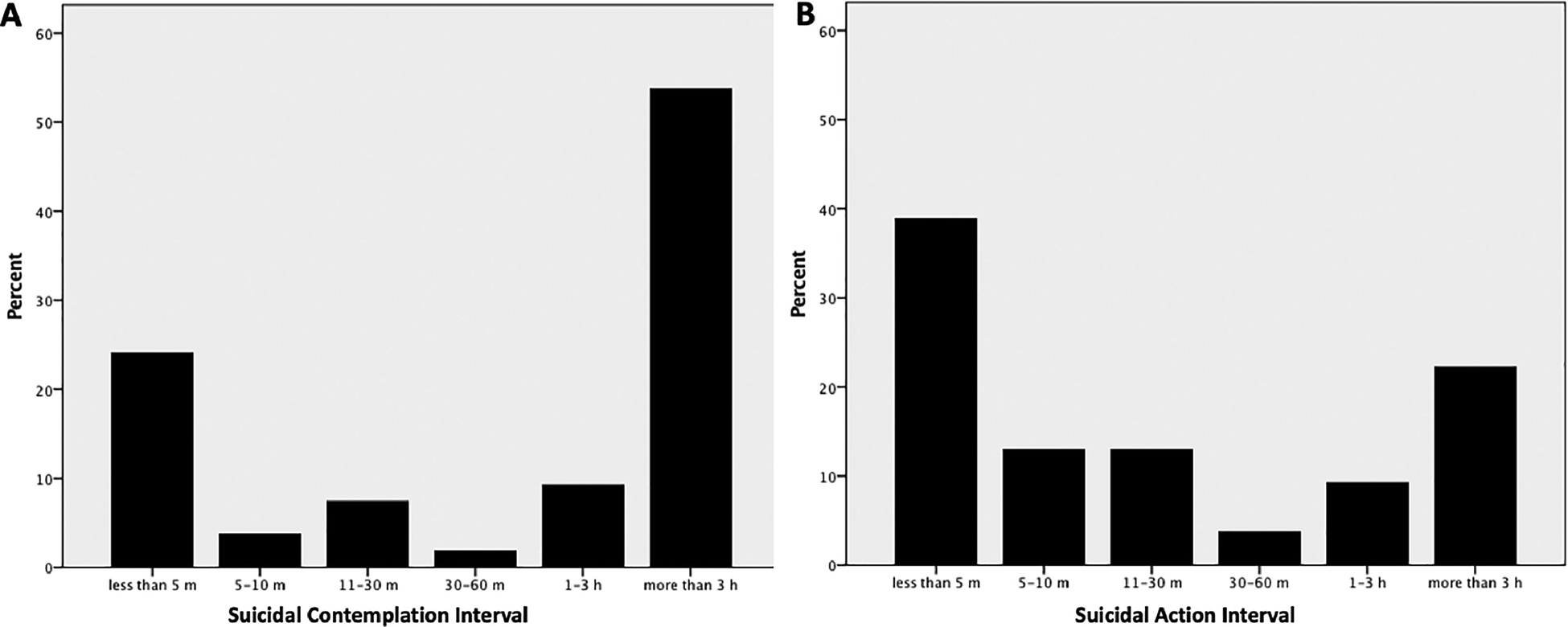

The average time from suicide attempt to our assessments was 34 hours. Table 3 summarizes the methods used by the Attempter group. The most common method used was drug overdose. Figure 1A shows a bimodal distribution of the suicide contemplation interval with a smaller peak (25% of the cases) of less than five minutes, and a larger peak (larger than 50%) longer than three hours. The suicidal action interval (Figure 1B) also showed a bimodal distribution; almost 40% of suicide attempters, took less than five minutes and approximately 25%, took longer than three hours.

Table 3.

Methods utilized by individuals in the suicide

| attempter group. | |

|---|---|

| Overdose | 34 (60%) |

| Cut neck or wrist/ stab chest | 10 (18%) |

| Hanging | 4 (7%) |

| Jumping off | 4 (7%) |

| Motor vehicle accident/ run into traffic | 3 (5%) |

| Gunshot | 2 (4%) |

Figure 1.

Time distribution of the duration of the suicidal process proximal to suicidal behavior. A. Suicide contemplation interval (time from onset of suicidal ideation to decision to kill oneself). B. Suicidal action interval (time from the decision to kill oneself to suicide attempt).

We expected to find a negative correlation between duration of the suicidal process and measures of time slowing and cognitive impulsivity, while we found no variables associated with the suicide contemplation interval, we found that time estimation of seven seconds (r= −.379; p=.003), 34 seconds (r= −.318; p=.004) and 25 minutes (r= .086; p=.011) and time production of 35 seconds ((r=.308; p=.006) and 43 seconds (r=.257; p =.023) were associated with duration of the suicidal action interval. Correlations with other time estimation and production intervals were not significant or did not survive multiple comparisons correction. Correlations between suicide contemplation or action intervals and cognitive impulsivity were not significant. Thus, we confirmed our hypothesis only for the negative correlation between duration of the suicidal process and time slowing but not for cognitive impulsivity.

Impulsive versus Non-impulsive suicide attempters

We expected to find increased time slowing in impulsive suicide attempters, and found that individuals with suicide contemplation interval shorter than three hours showed fewer education years (t = 2.812; p=.008), and increased time slowing, measured as shorter time production at 35s (t = 2.62; p=.011) and 43s (t = 2.131; p=.036), thus confirming our hypothesis. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of impulsive (suicidal contemplation interval < 3 hours) vs. non-impulsive suicide contemplation interval >3 hours) recent suicide attempters.

| Impulsive suicide attempters | Non-impulsive suicide attempters | Adjusted p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 30 | |

| Age | 30.7±10.5 | 35.3±9.7 | .056 |

| Gender (f) | 16 (59%) | 21 (71%) | .211 |

| Marital status | .127 | ||

| Never married | 3 (12%) | 6 (21%) | |

| Married | 5 (18%) | 9 (30%) | |

| Divorced/ widowed | 19 (70%) | 15 (50%) | |

| Education (years) | 12.0±2.1 | 13.2±2.0 | .006 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Depression (BDI) | 31.7±12.6 | 40.1±11.7 | .005 |

| Presence of anxiety disorder | 5 (20%) | 6 (21%) | .956 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | 25.6±14.2 | 31.6±14.7 | .082 |

| Hopelessness (BHS) | 9.5±1.8 | 10.3±2.8 | .155 |

| Individuals on antidepressant medications | 14 (52%) | 13 (48%) | .816 |

| Presence of substance use disorder (except tobacco) | 22 (80%) | 21 (77%) | .956 |

| Current smoking | 17 (63%) | 18 (59%) | .117 |

| Suicide related measures | |||

| Presence of suicidal ideation | 15 (55%) | 19 (63%) | .528 |

| Suicidal ideation severity (C-SSRS) | 1.3± 1.6 | 1.3±1.7 | .98 |

| Number of lifetime suicide attempts | 6.6±9.9 | 3.3±2.9 | .0211 |

| Suicide attempt lethality (most recent) | 1.6± 1.3 | 2.0±1.1 | .184 |

| Non-suicidal self-harm | 12 (44%) | 17 (57%) | .244 |

| Current physical pain | 4.1±3.1 | 3.6±3.3 | .530 |

| Current psychological pain | 5.2±3.8 | 6.0±3.6 | .374 |

| Cognitive and time measures | |||

| Small rewards choices | 6.3±2.3 | 6.4±2.0 | .846 |

| Medium rewards choices | 5.6±2.3 | 5.9±2.1 | .594 |

| Large rewards choices | 5.4±2.3 | 5.2±2.4 | .722 |

| Small losses choices | 5.4±3.0 | 5.1±2.7 | .626 |

| Medium losses choices | 4.8±3.0 | 5.1±2.8 | .596 |

| Large losses choices | 5.1±2.8 | 5.5±2.8 | .540 |

| Attentional impulsiveness (BIS) | 20.6±4.2 | 20.3±6.2 | .849 |

| Motor impulsiveness (BIS) | 25.6±5.2 | 27.5±6.7 | .417 |

| Non planning impulsiveness (BIS) | 28.6±7.4 | 29.5±6.3 | .735 |

| 7s Time Estimation | 8.7±3.0 | 8.0±3.3 | .310 |

| 34s Time Estimation | 42.8±26.7 | 34.6±15.4 | .194 |

| 90s Time Estimation | 95.9±48.0 | 85.7±42.6 | .334 |

| 25 min Time Estimation | 38.0±19.0 | 32.8±15.0 | .281 |

| 8s Time Production | 7.6±2.7 | 11.0±16.0 | .233 |

| 35s Time Production | 28.6±8.4 | 35.8±14.4 | .011 |

| 43 Time Production | 35.5±11.3 | 43.6±16.5 | .036 |

| 109s Time Production | 82.9±35.6 | 98.0±53.7 | .158 |

| Boys names in 1 min | 18.5±5.4 | 18.3±5.2 | .887 |

| TMT-A | 31.6±10.3 | 32.7±16.4 | .732 |

| TMT-B | 78.0±29.7 | 78.7±32.0 | .926 |

Mean ± standard deviation;

Chi-square between groups;

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; C-SSRS: Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale; BIS: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; TMT: Trail Making Test

Time judgment

We expected to find time judgment to be correlated with cognitive impulsivity, and found that delay discounting for rewards correlated with time estimation (25 minutes for all rewards and 90 seconds for large rewards). See Table 5. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no significant correlations with cognitive impulsivity for losses. Thus, our hypothesis was confirmed only for cognitive impulsivity regarding rewarding stimuli.

Table 5.

Correlation of time judgment with cognitive variables in the study population.

| Included variable | F(1,284) | R2 | p | Excluded variable | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small rewards | ||||||

| Estimation 25 min | 1.001 | .042 | .02 | Estimation 7 s | .175 | .861 |

| Estimation 34 s | −1.167 | .244 | ||||

| Estimation 90 s | 2.057 | .041 | ||||

| Production 8 s | 1.236 | .217 | ||||

| Production 35 s | −.211 | .833 | ||||

| Production 43 s | .912 | .363 | ||||

| Production 109 s | −.225 | .822 | ||||

| Verbal fluency | .287 | .774 | ||||

| TMT-A | −.154 | .878 | ||||

| TMT-B | .344 | .731 | ||||

| Medium Rewards | ||||||

| Estimation 25 min | 5.023 | .017 | .02 | Estimation 7 s | 1.232 | .219 |

| Estimation 34 s | −.044 | .965 | ||||

| Estimation 90 s | 1.708 | .089 | ||||

| Production 8 s | .206 | .837 | ||||

| Production 35 s | .318 | .750 | ||||

| Production 43 s | −.362 | .717 | ||||

| Production 109 s | −.416 | .678 | ||||

| Verbal fluency | .435 | .664 | ||||

| TMT-A | .003 | .998 | ||||

| TMT-B | .012 | .991 | ||||

| Large Rewards | ||||||

| Estimation 90 s | 4.684 | .016 | .031 | Estimation 7 s | .604 | .546 |

| Estimation 25 min | 4.706 | .03 | .01 | Estimation 34 s | −1.966 | .050 |

| Production 8 s | −.607 | .544 | ||||

| Production 35 s | −.041 | .967 | ||||

| Production 43 s | −.074 | .041 | ||||

| Production 109 s | −.319 | .750 | ||||

| Verbal fluency | −.047 | .962 | ||||

| TMT-A | −.409 | .683 | ||||

| TMT-B | −.105 | .917 |

TMT-A: Trail Making Test A; TMT-B: Trail Making Test B

Correlations with suicidal ideation

We expected to find time slowing to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation severity, and found that a significant effect of time estimation on suicidal ideation severity, Wilks Lambda=.82, F(3,26)=17.08, p<.001, with pairwise comparisons at 43s and 90s significant, p<.01. A second repeated measures general linear model indicated a significant effect of time production on suicidal ideation severity, Wilks’ Lambda=.83, F(3,262)=16.77, p=.001, with pairwise comparisons were significant for all time intervals, p<.01. No significant contributions were seen from age and depression severity covariates. Thus, we confirmed our hypothesis.

4. Discussion

Our main findings were: a) bimodal distributions for both the suicide contemplation and action intervals, ~40% of attempters took less than 5 minutes from decision to attempt; time slowing correlated negatively with the suicidal action interval (time from the decision to kill oneself to suicide attempt); b) individuals with suicide contemplation interval shorter than three hours showed increased time slowing; c) cognitive impulsivity for rewarding stimuli positively correlated with time estimation at long intervals; and d) suicidal ideation severity was positively correlated with time slowing.

Our findings of a bimodal distribution of the duration of the suicidal process highlight the heterogeneity of suicide. The first peak represents an almost fulminant course of only a few minutes. The second peak denotes a more deliberated event occurring over longer than three hours to several days or weeks. This pattern is consistent with previous reports (Deisenhammer et al., 2009; Kattimani et al., 2016; Millner et al., 2017; Pearson et al., 2002; Williams et al., 1980). The positive correlation of time slowing or dilation with the intensity (suicidal ideation severity) and negatively with the duration of the suicidal process (suicide contemplation and action intervals) is suggestive of derealization- or depersonalization-type phenomena. For instance, dissociation has been linked to the development of suicidal ideation in soldiers (Shelef et al., 2014). Moreover, dissociative disorders are associated with a history of recent suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm (Webermann et al., 2016) and history of multiple suicide attempts (Foote et al., 2008). Time slowing has been described during experimental dissociation and in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (Brewin et al., 2013; Vicario and Felmingham, 2018). The experience of time slowing or dilation in suicidal patients, likely triggered by overwhelming psychological pain, may in turn worsen the perception of inescapability from psychological pain. It could be hypothesized that the height of a suicidal crisis could be a dissociative-like state, triggered by overwhelming psychological pain and characterized by a slowed perception of time.

To our knowledge, only one previous study surveyed time processing in suicidal patients. Williams et al., reported that individuals who attempted suicide by drug overdose showed deficits in imagining the future concretely (Williams et al., 1996). Increased time slowing or dilation has been triggered by threatening, negative, or fearful stimuli (Bar-Haim et al., 2010; Droit-Volet and Gil, 2009, 2016) and even by socially stressful situations (van Hedger et al., 2017). Thus, a case could be made the increased time slowing in individuals with suicidal thoughts may be related to the intensity of the negative emotional state experienced during stressful psychosocial circumstances. The relatively weak correlations between duration of the suicide process and time slowing suggest that presence of other relevant factors in addition to time judgement abnormalities.

At least 50% of suicide attempts are considered impulsive (Deisenhammer et al., 2009). Impulsivity is a construct that includes several modalities (Klonsky and May, 2010). Thus, not surprisingly, the literature of impulsivity in relation to suicidal behavior is mixed (Anestis et al., 2014; Baca-Garcia et al., 2001; Jimenez et al., 2016; Klonsky and May, 2010). We aimed to examine the cognitive states that occur during or temporally very close to suicidal behavior. Increased delay discounting, a state measure of cognitive impulsivity, was elevated in adult acutely suicidal patients and normalized within one week (Cáceda et al., 2014). Increased cognitive impulsivity was positively correlated with lifetime severity of suicide attempts in bipolar patients (Swann et al., 2005). The differential measures of our suicidal and depressed patients regarding cognitive impulsivity for gains and losses suggest specific abnormalities in the processing of gains or positive rewards in acutely suicidal patients, while aversion to losses seems no different between suicidal and non-suicidal depressed patients. This would support the notion that recent suicide attempters would act more impulsively for hedonic-related outcomes, such as the removal of psychological pain, even at the expense of their own future life experience. Depression and suicidal states may amplify the differential valuation of rewards and losses seen in healthy individuals in everyday activities (Alves et al., 2017).

In our study, recent suicide attempters showed elevated cognitive impulsivity compared with depressed patients without recent suicidal behavior, regardless of the presence of suicidal thoughts. We hypothesize that impulsive individuals may be so because of an altered sense of time. Impulsive individuals may choose smaller sooner rewards because time may be perceived to last too long, generating too high a cost (Wittmann and Paulus, 2008). This is exemplified in the general (Baumann and Odum, 2012) and in clinical populations that show increased cognitive impulsivity and slower perception of time, such as patients with orbitofrontal cortex lesions (Berlin et al., 2004), stimulant use disorder (Wittmann et al., 2007b) and borderline personality disorder (Barker et al., 2015). Lastly, common brain regions, frontoparietal cortices and limbic regions seem to underlie both cognitive impulsivity (Bickel et al., 2009; McClure et al., 2007) and time processing (Kulashekhar et al., 2016; Li et al., 2015; Wittmann et al., 2011).

We found time slowing, (at longer intervals) common to all depressed groups. The experience of time slowing or dilation has been reported in depressed patients (Bschor et al., 2004; Kitamura and Kumar, 1983; Kornbrot et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2018; Wyrick and Wyrick, 1977), although not uniformly. However, a meta-analysis reported no significant differences in time perception in depressed patients (Thones and Oberfeld, 2015); studies sample size and heterogeneity in sample selection may have confounded these findings. Our study adds to the field with the investigation of time judgment in a large sample of severely depressed patients. Our data is in line with the predictions of a faster running internal clock (Gibbon et al., 1984; Treisman, 1963) in depressed patients. We replicated Bschor et al. findings of time slowing only in time production tasks, which is possibly explained by higher variability of the time estimation data. Perception of time slowing has been associated with a common symptom of depression: psychomotor retardation (Kitamura and Kumar, 1983). Our finding of longer time to complete the Trail Making Test A in all depressed groups replicated previous findings and support this notion (Bschor et al., 2004). As previously reported (Oberfeld et al., 2014), we did not find a correlation between depression severity and time perception.

Certain discrepancies in our findings are worth noting. Slowing of time in the depressed groups was noted only at longer intervals (43 and 109 s), as described previously (Bschor et al., 2004). This may be explained by the proposed differential mechanisms thought to underlie perception of shorter time intervals (Aschoff, 1998; Lake et al., 2016; Podvigina and Lyakhovetskii, 2011). From a mechanistic standpoint, time slowing or dilation has been associated with activity in cortical midline structures, i.e. middle frontal, medial and posterior cingulate in studies in healthy participants (van Wassenhove et al., 2011). Impaired neural synchrony may be a consequence of blunted amplitudes of oscillations in monoaminergic measures, which are relevant to both mood (Salomon and Cowan, 2013) and time perception (Wittmann et al., 2007a). Speculatively, the abnormalities described in anterior and posterior cortical midline structures in a variety of suicidal individuals may be among the neural substrates for time slowing (Caceda et al., 2018; Du et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2017; Olie et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016).

The main clinical implications of this research lie in the identification of a significant number of patients with a very limited time (~40% within 5 minutes, ~75% within three hours between the decision to take one’s life and suicidal action) for intervention. This reinforces the need for a variety of preventive strategies that target overlapping risk factors. For example, expanded screening and treatment for mental illness may decrease the number of individuals with untreated severe mental illness who develop suicidal thoughts. Suicide-specific preemptive strategies include lifestyle modification (Berardelli et al., 2018), raise awareness of the seriousness of suicidal communications (Pompili et al., 2016), safety planning (Stanley and Brown, 2012) and suicide means restriction (access to firearms, pesticides and bridge enclosures) (Hawton et al., 1998; Knipe et al., 2017). Moreover, the immediate pre-attempt phases of the duration of the suicidal process are also characterized by an inability to express one’s own vicissitudes and an inability to ask for help (Wasserman et al., 2008), thus emphasizing the value of improving communication skills and safety planning (Stanley and Brown, 2012).

Our sample included individuals who still were or had been in an acute suicidal crisis within the last few hours. This sample was demographically heterogeneous and comprised of severely depressed patients with various diagnoses: major depression, bipolar disorder or unspecified depression. To avoid further arbitrary measures in the field we based our assessments in previous methodologically rigorous reports, such as the three-hour cut-off for the duration of suicidal action interval (Bagge et al., 2013; Millner et al., 2017) and established tasks of time estimation and production (Bschor et al., 2004).

The limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design and that our assessment of the duration of the suicidal process was based on self-report and subject to recall bias. The recall bias is somewhat minimized given the relatively short delay from attempt to our assessments (average was 34 hours). It is possible that the individual variability in completing our different tasks would be influenced by the considerable stress that patients have been experiencing at the time of recruitment (suicidal crisis, recent hospitalization, uncertainty about length of hospitalization and reinsertion to family and work-life) and the demands on their sustained cooperation. As with other studies of recent suicide attempters, five days provides only a close but not perfect approximation to the cognitive state of individuals who attempted suicide. This is an intrinsic limitation of research attempting to understand acute suicidal behavior. Our patients were not medication free. It is unknown if antidepressants and mood stabilizers have an effect on time processing. Our results could have been influenced by the sedative effects of drug overdoses (60%) of suicide attempters or recovery from anesthetics given in medical procedures; however, this is unlikely since participants had to be awake, alert and cognizant to participate in the clinical intake interview and the informed consent process. Both Suicide Attempter and Suicidal Ideator groups had more severe depression, more lifetime suicide attempts and were all inpatient, in contrast with the non-suicidal depressed group. This in part reflects the study design of having specific control groups for suicidal behavior, ideation and depression. We did not measure Axis II pathology. Most of our assessments were performed in the late morning or early afternoon, which could reduce additional variability due to potential due to circadian rhythm effects on time processing. The suicide attempt group had less severe suicidal ideation than the suicidal ideation group, which was similar to previous findings in a different sample (Cáceda et al., 2014), and to recent suicide attempters as compared to distant attempters (Paashaus et al., 2019). All patients in the Ideator group endorsed suicidal ideation the morning of recruitment, a finding compatible with the known fluctuation and fleetingness of suicidal ideation (Kleiman and Nock, 2018; Kleiman et al., 2017). Moreover, for many patients suicide attempt is a cathartic event and suicidal ideation and intention decreases considerably shortly after a failed suicide attempt (Rosen, 1976).

We confirmed a bimodal distribution of the duration of the suicidal process (Deisenhammer et al., 2009). Time slowing or dilation was associated with two critical elements of the suicidal process: its duration and suicidal ideation severity. It is possible that time processing abnormalities in suicidal individuals may be caused by the intense emotional nature of suicidal crises, e.g. overwhelming psychological pain. Time slowing or dilation may be a sign of a dissociative-like state that may hasten the suicidal process.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Slowing of time during longer time intervals in all depressed groups.

Bimodal distributions for both the suicide contemplation and action intervals.

Time slowing correlated with suicidal process duration and suicidal ideation.

Time slowing may be a sign of a dissociative-like state found in suicidal crisis.

Role of Funding Source

This work was partially funded by the Clinician Scientist Program of the University Arkansas for Medical Sciences and by the TRI NCATS UL1TR000039. The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alves H, Koch A, Unkelbach C, 2017. Why Good Is More Alike Than Bad: Processing Implications. Trends Cogn Sci 21, 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Soberay KA, Gutierrez PM, Hernandez TD, Joiner TE, 2014. Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 18, 366–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschoff J, 1998. Human perception of short and long time intervals: its correlation with body temperature and the duration of wake time. J Biol Rhythms 13, 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Sastre C, Basurte E, Prieto R, Ceverino A, Saiz-Ruiz J, de Leon J, 2001. A prospective study of the paradoxical relationship between impulsivity and lethality of suicide attempts. J Clin Psychiatry 62, 560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Littlefield AK, Lee HJ, 2013. Correlates of proximal premeditation among recently hospitalized suicide attempters. J Affect Disord 150, 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Kerem A, Lamy D, Zakay D, 2010. When time slows down: The influence of threat on time perception in anxiety. Cognition & Emotion 24, 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Barker V, Romaniuk L, Cardinal RN, Pope M, Nicol K, Hall J, 2015. Impulsivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med 45, 1955–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Odum AL, 2012. Impulsivity, risk taking, and timing. Behav Processes 90, 408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, 1988. Beck Hopelessness Scale. The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, 1990. BAI, Beck anxiety inventory : manual. Psychological Corp. : Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Antonio. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W, 1996. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 67, 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardelli I, Corigliano V, Hawkins M, Comparelli A, Erbuto D, Pompili M, 2018. Lifestyle Interventions and Prevention of Suicide. Front Psychiatry 9, 567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin HA, Rolls ET, Kischka U, 2004. Impulsivity, time perception, emotion and reinforcement sensitivity in patients with orbitofrontal cortex lesions. Brain 127, 1108–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJ, 2009. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: fictive and real money gains and losses. J Neurosci 29, 8839–8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Ma BY, Colson J, 2013. Effects of experimentally induced dissociation on attention and memory. Conscious Cogn 22, 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bschor T, Ising M, Bauer M, Lewitzka U, Skerstupeit M, Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Baethge C, 2004. Time experience and time judgment in major depression, mania and healthy subjects. A controlled study of 93 subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109, 222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceda R, Bush K, James GA, Stowe ZN, Kilts CD, 2018. Modes of Resting Functional Brain Organization Differentiate Suicidal Thoughts and Actions: A Preliminary Study. J Clin Psychiatry 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceda R, Durand D, Cortes E, Prendes S, Moskovciak TN, Harvey PD, Nemeroff CB, 2014. Impulsive choice and psychological pain in acutely suicidal depressed patients. Psychosomatic Medicine 76, 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceda R, Kordsmeier NC, Golden E, Gibbs HM, Delgado PL, 2017. Differential Processing of Physical and Psychological Pain during Acute Suicidality. Psychother Psychosom 86, 116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbajal JM, Gamboa JL, Moore J, Smith F, Eads L, Clothier J, Caceda R, 2017. Response to unfairness across the suicide risk spectrum. Psych Res 258, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisenhammer EA, Ing CM, Strauss R, Kemmler G, Hinterhuber H, Weiss EM, 2009. The duration of the suicidal process: how much time is left for intervention between consideration and accomplishment of a suicide attempt? J Clin Psychiatry 70, 19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet S, Gil S, 2009. The time-emotion paradox. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364, 1943–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet S, Gil S, 2016. The emotional body and time perception. Cogn Emot 30, 687–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Zeng JK, Liu H, Tang DJ, Meng HQ, Li YM, Fu YX, 2017. Fronto-limbic disconnection in depressed patients with suicidal ideation: A resting-state functional connectivity study. Journal of Affective Disorders 215, 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote B, Smolin Y, Neft DI, Lipschitz D, 2008. Dissociative disorders and suicidality in psychiatric outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 196, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH, 1984. Scalar timing in memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci 423, 52–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs HM, Davis L, Han X, Clothier J, Eads LA, Caceda R, 2016. Association between C-reactive protein and suicidal behavior in an adult inpatient population. J Psychiatr Res 79, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Fagg J, Simkin S, Harriss L, Malmberg A, 1998. Methods used for suicide by farmers in England and Wales. The contribution of availability and its relevance to prevention. Br J Psychiatry 173, 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez E, Arias B, Mitjans M, Goikolea JM, Ruiz V, Brat M, Saiz PA, Garcia-Portilla MP, Buron P, Bobes J, Oquendo MA, Vieta E, Benabarre A, 2016. Clinical features, impulsivity, temperament and functioning and their role in suicidality in patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 133, 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jollant F, Voegeli G, Kordsmeier NC, Carbajal JM, Richard-Devantoy S, Turecki G, Caceda R, 2019. A visual analog scale to measure psychological and physical pain: A preliminary validation of the PPP-VAS in two independent samples of depressed patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 90, 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SG, Na KS, Choi JW, Kim JH, Son YD, Lee YJ, 2017. Resting-state functional connectivity of the amygdala in suicide attempters with major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 77, 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattimani S, Sarkar S, Menon V, Muthuramalingam A, Nancy P, 2016. Duration of suicide process among suicide attempters and characteristics of those providing window of opportunity for intervention. J Neurosci Rural Pract 7, 566–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK, 1999. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen 128, 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Kumar R, 1983. Time estimation and time production in depressive patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 68, 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Nock MK, 2018. Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Curr Opin Psychol 22, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Huffman JC, Nock MK, 2017. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J Abnorm Psychol 126, 726–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May A, 2010. Rethinking impulsivity in suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 40, 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Qiu T, Saffer BY, 2017. Recent advances in differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators. Curr Opin Psychiatry 30, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe DW, Chang SS, Dawson A, Eddleston M, Konradsen F, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D, 2017. Suicide prevention through means restriction: Impact of the 2008–2011 pesticide restrictions on suicide in Sri Lanka. PLoS One 12, e0172893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbrot DE, Msetfi RM, Grimwood MJ, 2013. Time perception and depressive realism: judgment type, psychophysical functions and bias. PLoS One 8, e71585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulashekhar S, Pekkola J, Palva JM, Palva S, 2016. The role of cortical beta oscillations in time estimation. Hum Brain Mapp 37, 3262–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JI, LaBar KS, Meck WH, 2016. Emotional modulation of interval timing and time perception. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 64, 403–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Mo L, Chen Q, 2015. Differential contribution of velocity and distance to time estimation during self-initiated time-to-collision judgment. Neuropsychologia 73, 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Trout ZM, Hernandez EM, Cheek SM, Gerlus N, 2017. A behavioral and cognitive neuroscience perspective on impulsivity, suicide, and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analysis and recommendations for future research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Ericson KM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD, 2007. Time discounting for primary rewards. J Neurosci 27, 5796–5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, Nock MK, 2017. Describing and Measuring the Pathway to Suicide Attempts: A Preliminary Study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 47, 353–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Baumann AA, Green L, 2014. Discounting of delayed rewards: (A)theoretical interpretation of the Kirby questionnaire. Behav Processes 107, 99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman J, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, 2004. The suicidal process; prospective comparison between early and later stages. J Affect Disord 82, 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe, F., 1969. Missile wounds of the brain: a study of psychological deficits. Oxford U.P., London,. [Google Scholar]

- Oberfeld D, Thones S, Palayoor BJ, Hecht H, 2014. Depression does not affect time perception and time-to-contact estimation. Front Psychol 5, 810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olie E, Ding Y, Le Bars E, de Champfleur NM, Mura T, Bonafe A, Courtet P, Jollant F, 2015. Processing of decision-making and social threat in patients with history of suicidal attempt: A neuroimaging replication study. Psychiatry Res 234, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olie E, Guillaume S, Jaussent I, Courtet P, Jollant F, 2010. Higher psychological pain during a major depressive episode may be a factor of vulnerability to suicidal ideation and act. J Affect Disord 120, 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paashaus L, Forkmann T, Glaesmer H, Juckel G, Rath D, Schönfelder A, Engel P, Teismann T, 2019. Do suicide attempters and suicide ideators differ in capability for suicide? Psychiatry Res 275, 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES, 1995. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson V, Phillips MR, He F, Ji H, 2002. Attempted suicide among young rural women in the People’s Republic of China: possibilities for prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behav 32, 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podvigina DN, Lyakhovetskii VA, 2011. Characteristics of the Perception of Short Time Intervals. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology 41, 936–941. [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Belvederi Murri M, Patti S, Innamorati M, Lester D, Girardi P, Amore M, 2016. The communication of suicidal intentions: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 46, 2239–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ, 2011. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 168, 1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R, Wolfson D, 1985. The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. Neuropsychology Press, Tucson. [Google Scholar]

- Richard-Devantoy S, Berlim MT, Jollant F, 2014. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological markers of vulnerability to suicidal behavior in mood disorders. Psychol Med 44, 1663–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DH, 1976. Suicide survivors: psychotherapeutic implications of egocide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 6, 209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runeson B, Tidemalm D, Dahlin M, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N, 2010. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. BMJ 341, c3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon RM, Cowan RL, 2013. Oscillatory serotonin function in depression. Synapse 67, 801–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelef L, Levi-Belz Y, Fruchter E, 2014. Dissociation and acquired capability as facilitators of suicide ideation among soldiers. Crisis 35, 388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown GK, 2012. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 19, 256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia PJ, Pham M, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG, 2005. Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 162, 1680–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thones S, Oberfeld D, 2015. Time perception in depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 175, 359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman M, 1963. Temporal discrimination and the indifference interval. Implications for a model of the “internal clock”. Psychol Monogr 77, 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hedger K, Necka EA, Barakzai AK, Norman GJ, 2017. The influence of social stress on time perception and psychophysiological reactivity. Psychophysiology 54, 706–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heeringen K, Wu GR, Vervaet M, Vanderhasselt MA, Baeken C, 2017. Decreased resting state metabolic activity in frontopolar and parietal brain regions is associated with suicide plans in depressed individuals. J Psychiatr Res 84, 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wassenhove V, Wittmann M, Craig AD, Paulus MP, 2011. Psychological and neural mechanisms of subjective time dilation. Front Neurosci 5, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicario CM, Felmingham KL, 2018. Slower Time estimation in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Sci Rep 8, 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DHV, Kramer K, Schoofs T, Kupke C, Vogeley K, 2018. Disturbed Experience of Time in Depression-Evidence from Content Analysis. Front Hum Neurosci 12, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman D, Tran Thi Thanh H, Pham Thi Minh D, Goldstein M, Nordenskiold A, Wasserman C, 2008. Suicidal process, suicidal communication and psychosocial situation of young suicide attempters in a rural Vietnamese community. World Psychiatry 7, 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webermann AR, Myrick AC, Taylor CL, Chasson GS, Brand BL, 2016. Dissociative, depressive, and PTSD symptom severity as correlates of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality in dissociative disorder patients. J Trauma Dissociation 17, 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Davidson JA, Montgomery I, 1980. Impulsive suicidal behavior. J Clin Psychol 36, 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Ellis NC, Tyers C, Healy H, Rose G, MacLeod AK, 1996. The specificity of autobiographical memory and imageability of the future. Mem Cognit 24, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Carter O, Hasler F, Cahn BR, Grimberg U, Spring P, Hell D, Flohr H, Vollenweider FX, 2007a. Effects of psilocybin on time perception and temporal control of behaviour in humans. J Psychopharmacol 21, 50–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Leland DS, Churan J, Paulus MP, 2007b. Impaired time perception and motor timing in stimulant-dependent subjects. Drug Alcohol Depend 90, 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Paulus MP, 2008. Decision making, impulsivity and time perception. Trends Cogn Sci 12, 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Simmons AN, Flagan T, Lane SD, Wackermann J, Paulus MP, 2011. Neural substrates of time perception and impulsivity. Brain Res 1406, 43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrick RA, Wyrick LC, 1977. Time experience during depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 34, 1441–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Chen JM, Kuang L, Cao J, Zhang H, Ai M, Wang W, Zhang SD, Wang SY, Liu SJ, Fang WD, 2016. Association between abnormal default mode network activity and suicidality in depressed adolescents. Bmc Psychiatry 16, 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.