Abstract

In the last decade, an emerging three-dimensional (3D) printing technique named freeform 3D printing has revolutionized the biomedical engineering field by allowing soft matters with or without cells to be printed and solidified with high precision regardless of their poor self-supportability. The key to this freeform 3D printing technology is the supporting matrices that hold the printed soft ink materials during omnidirectional writing and solidification. This approach not only overcomes structural design restrictions of conventional layer-by-layer printing but also helps to realize 3D printing of low-viscosity or slow-curing materials. This article focuses on the recent developments in freeform 3D printing of soft matters such as hydrogels, cells, and silicone elastomers, for biomedical engineering. Herein, we classify the reported freeform 3D printing systems into positive, negative, and functional based on the fabrication process, and discuss the rheological requirements of the supporting matrix in accordance with the rheological behavior of counterpart inks, aiming to guide development and evaluation of new freeform printing systems. We also provide a brief overview of various material systems used as supporting matrices for freeform 3D printing systems and explore the potential applications of freeform 3D printing systems in different areas of biomedical engineering.

Keywords: Additive manufacturing, Freeform 3D printing, Supporting matrix, Soft matters, Biomedical engineering

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), or 3D printing is a diversified and promising technology to fabricate three-dimensional objects using computer-aided designs through a layer-by-layer manufacturing approach. There are more than 50 different types of AM systems in the market which can be categorized by the type of processes used, namely, direct energy deposition, material extrusion, material jetting, binder jetting, powder bed fusion, vat photopolymerization, and sheet lamination [1]. The ability of AM technology to manufacture complex and customizable objects with good precision and resolution creates wide-ranging applications in automotive [2], aerospace [3], construction [4], food [5], water treatment [6], marine [7], and biomedical industries [8]. AM in the biomedical field, also known as bioprinting, involves the printing of biomaterials, living cells, and other biomolecules primarily for tissue engineering applications. Research works in bioprinting have adopted various techniques including extrusion-based printing [9], inkjet printing [10, 11], drop-on-demand printing [12, 13], and laser printing [14, 15] to control the deposition of living cells and biomaterials. However, the challenge of bioprinting is the difficulty in retaining the three-dimensional structures and shapes of soft delicate materials like hydrogels, cells, biopolymers, and silicones, etc. without additional support. As such, previous research efforts were focused on developing special bio-inks for efficient deposition and printability through chemical or mechanical enhancement [16–19].

In recent years, an emerging printing approach, the freeform 3D printing systems began to attract the attention of researchers due to its major advantage in allowing the deposition of low viscosity materials within a supporting matrix. The embedment of printed materials within the supporting matrix prevents the collapse of soft materials and ensures that print fidelity and structural integrity of printed structures could be achieved. The freeform 3D printing system was first introduced by Wu et. al [20] in 2011 as a variant of direct ink writing (DIW) for the fabrication of 3D microvascular networks. Since then, numerous freeform 3D printing systems with different types of supporting matrices have been developed. To date, there are approximately 23 types of supporting matrix materials reported in publications. Freeform 3D printing systems have great potential in addressing the existing challenges in the printing of soft matters and can possibly lead to the development of new material systems and fabrication processes for bioprinting. Therefore, this article aims to provide an overview of the recent advances in freeform 3D printing of soft matters for biomedical engineering, by reviewing the various types of freeform 3D printing systems and their supporting matrices, and exploring existing and potential applications of these printing systems.

Freeform 3D printing systems

Generally, freeform 3D printing refers to the new printing approach that involves two major components, i.e. the printing materials and the supporting matrices. In the present state-of-art, freeform 3D printing systems primarily utilize extrusion-based printing techniques. During the printing process, the materials are deposited according to the designed printing path within the supporting matrices. Both supporting matrices and printing materials are usually shear-thinning and viscoplastic, with matched yield stresses and shear moduli such that stable deposition, undisrupted embedment of materials, and good print fidelity could be achieved. The rheological properties of supporting matrices and the importance of mechanical compatibility between a supporting matrix and a printing material would be elaborated in the later section. In this session, freeform 3D printing systems will be classified into three main categories, positive freeform 3D printing, negative freeform 3D printing, and functional freeform 3D printing depending on the detailed processing methods. The general criteria of materials used for a supporting matrix and its counterpart ink of each freeform 3D printing systems are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

General criteria for the supporting matrix materials and the ink materials in freeform 3D printing systems

| Printing systems | Requirements of supporting matrix material | Requirements of ink material |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 1. Reasonable rheological properties for 3D freeform printing process | 1. Consisting of a curable material |

| 2. Chemical and structural stability during ink solidification | 2. Structural stability of solidified ink after releasing from the supporting matrix | |

| 3. Easily removed to release printed objects | ||

| 4. Good transparency for photo-cross-linkable inks | ||

| 5. Recyclable for multiple printing processes | ||

| Negative | 1. Reasonable rheological properties for 3D freeform printing process | 1. Chemical and structural stability during matrix solidification |

| 2. Consisting of a curable material | 2. Easily removed by air or water flow | |

| 3. Structural stability of the solidified matrix after ink removal | ||

| Functional | 1. Reasonable rheological properties for 3D freeform printing process | 1. Applicable to a solidification mechanism with additional functionality such as mechanical, biological, electrical or magnetic properties |

| 2. Applicable to a solidification mechanism or easily removed to release printed objects | 2. Structural stability of solidified ink after releasing from the supporting matrix | |

| 3. Structural stability during ink solidification | 3. Likely containing precursors or functional groups which can react with a supporting material system | |

| 4. Good transparency for photo-cross-linkable inks | ||

| 5. Likely containing precursors or functional groups which can react with an ink system |

Positive freeform 3D printing systems

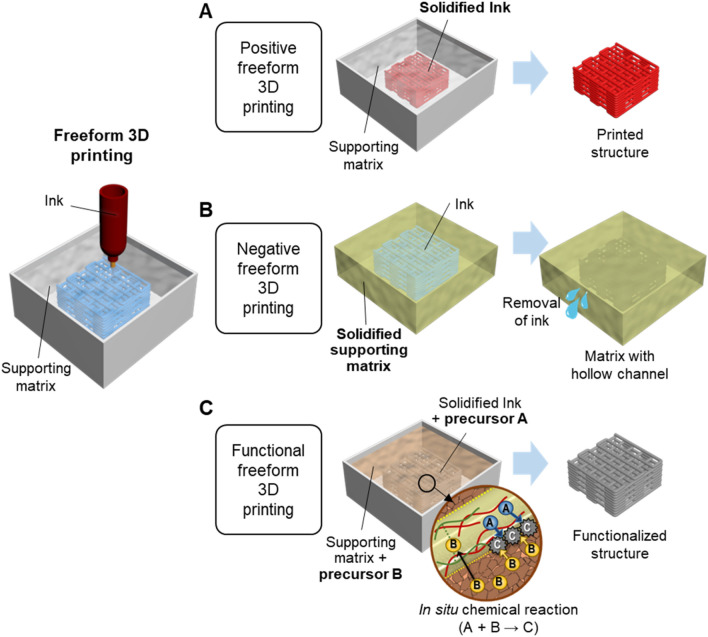

Positive freeform 3D printing refers to the printing process of a curable ink in a removable supporting matrix. Similar to conventional extrusion 3D printing, the final product obtained from the whole process is the printed material or the ink. The supporting matrix serves as a medium to retain and support the extrusion and solidification of the ink, enabling the high-quality printing of soft or slow curing materials which were previously considered non-printable [21–23]. The complete process of positive printing includes 3D printing of a curable ink in a supporting matrix, solidification of ink, and release of the crosslinked structure, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The supporting matrix plays an important role in both printing and post-printing processes. It not only allows the nozzle to move through and deposit the ink omnidirectionally during printing but also holds the embedded ink in place until the construct fully solidifies during the post-printing process. To fulfill these tasks, the supporting matrix material needs to possess the necessary rheological properties [24]. In addition, the supporting matrix for positive freeform 3D printing needs to remain stable during the crosslinking of the ink, without any unintentional chemical interaction or mechanical interference with the ink [25]. The removal and washing steps of the supporting matrix should not deter the fidelity of complex structures when the printed object is released from the matrix [26]. For the scalability and cost-effectiveness of this printing system, the recyclability of a supporting matrix should be an additional requirement.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of freeform 3D printing process and the three types of freeform 3D printing systems. a Positive freeform 3D printing systems, b negative freeform 3D printing systems, c functional freeform 3D printing systems

Negative freeform 3D printing systems

Negative freeform 3D printing is an opposite process from positive printing, in which the matrix will be the final product instead of the extruded ink. A fugitive or sacrificial ink is used to draw an internal pattern and will be finally removed to create hollow channels. As depicted in Fig. 1b, the complete process of negative printing usually involves freeform 3D printing of a sacrificial ink, solidification of the supporting matrix, and removal of the ink [27, 28]. In this case, the supporting matrix needs to be composed of cross-linkable materials. One of the popular crosslinking mechanism is photo-crosslinking. The supporting matrix material is either conjugated with photo-cross-linkable functional groups [20, 29, 30] or incorporated with secondary photo-cross-linkable materials [31] to make it curable under UV irradiation after freeform 3D printing. Other approaches for the solidification of the supporting matrix are drying [32] and thermal gelation [33]. Besides, the ink material should be easily removed by air or water flow afterward. The commonly used sacrificial inks are hydrogels that can undergo temperature-dependent gel-liquid transition such as gelatin [33, 34] and Pluronic F127 [20, 35].

Functional freeform 3D printing systems

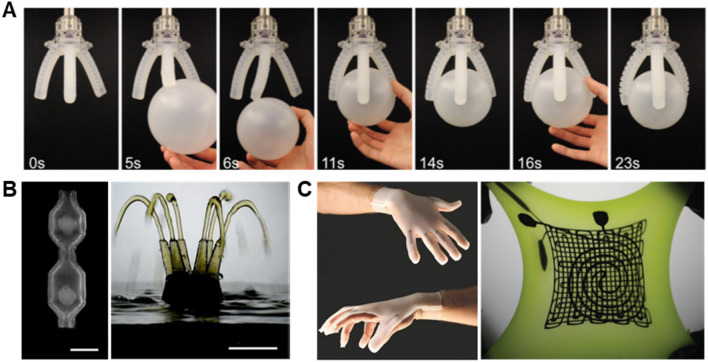

A few systems focus more on the functionalization of a printed material besides its printability. Here, we referred to this type of system as the functional freeform 3D printing system. A schematic example of this system is shown in Fig. 1c. Chen et al. [36] incorporated phosphate ions in the hydrogel ink as a precursor (precursor A), and calcium ions in the supporting matrix as a counterpart precursor (precursor B), to trigger the in situ precipitation of calcium phosphate (CaP) nanoparticles (A + B → C). With this reactive freeform printing approach, nanocomposite hydrogel scaffolds with different CaP content can be fabricated. Also, Forth et al. [37] chose nanoparticles conjugated with carboxylic acid groups ( − COOH) as the ink, and polydimethlsiloxane (PDMS) with amine groups ( − NH2) as the supporting matrix, respectively. When the ink containing COOH-functionalized nanoparticles was extruded into the NH2-functionalized PDMS matrix, nanoparticle surfactant films were generated at the interface to stabilize the printed pattern. This mechanism enables the fabrication of complex structures within two aqueous phases. Jeon et al. [38] prepared an oxidized, methacrylated alginate (OMA) microgel-based slurry for 3D printing of cell-only bioinks. After the embedment of ink, the slurry was photo-crosslinked to support the cell structure during 4 weeks of culture. The self-assembled tissue construct could be released from the supporting matrix by mechanical force. Another type of functional freeform 3D printing system includes the works conducted by Lewis and co-workers [35, 39], where a conductive ink that can be embedded in the elastomer reservoir matrix via freeform 3D printing was developed. The elastomer matrix was subsequently cured to harvest functional soft sensors [39] or sensitive actuators [35].

Supporting matrix

Rheological properties

Yield stress

One of the major components in freeform 3D printing is the supporting matrix. To enable freeform 3D printing, the supporting matrix must meet several criteria. First and most importantly, the supporting matrix materials must be viscoplastic with a yield-stress (σy), which is the threshold stress from solid to liquid states, allowing a solid-like fluid to flow. The material will flow like a liquid when the applied stress (σ) is higher than yield stress (σ > σy), whereas it behaves like a solid when σ < σy. During 3D freeform printing, the solid–liquid transition of a supporting matrix ensures smooth translation of the nozzle in the supporting matrix without mechanical resistance at σ > σy, while the solid-like behavior allows the supporting matrix to maintain the structural integrity and position of the printed objects [21, 24, 27, 40, 41].

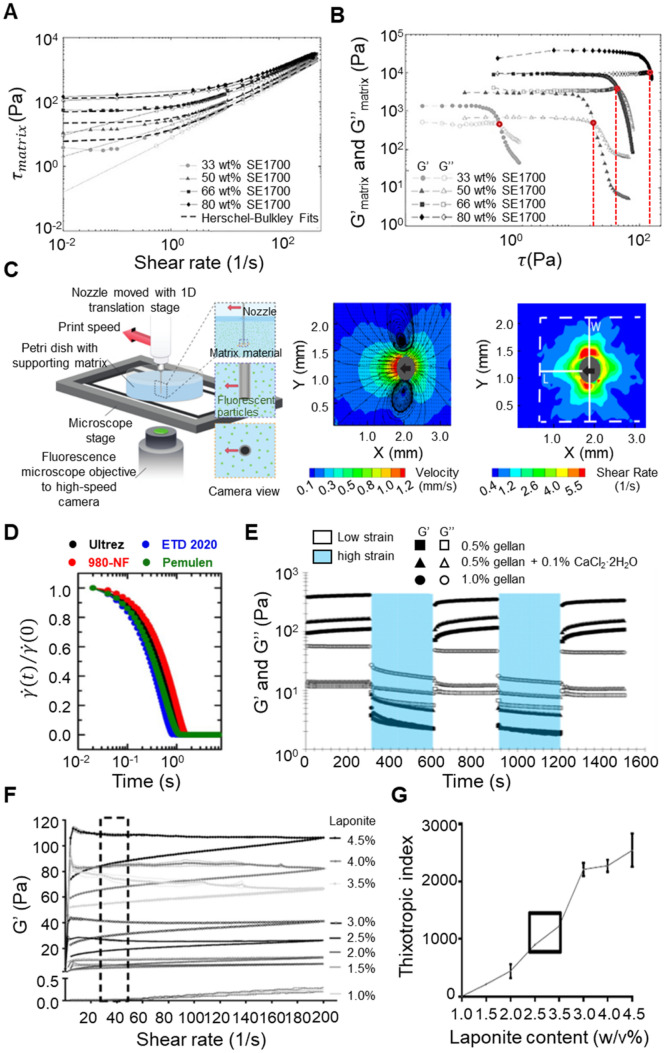

There are generally two methods used by researchers to obtain the yield stress of a supporting matrix from rheological measurements. The first method is to determine the minimum stress to make the supporting matrix start to flow (static yield stress) or the minimum stress to make the matrix keep or stop flowing (dynamic yield stress) depending on increasing or decreasing shear rates [25, 41–44]. Experimentally, the static yield stress can be acquired from the shear stress of the supporting matrix at the shear rate of zero in an ascending shear-rate ramp test while the dynamic yield stress can be acquired in a descending shear-rate ramp test [45]. In order to obtain the static or dynamic yield stress, the shear stress-shear rate curve is fit with a viscoplastic model such as the Herschel–Bulkley (H–B) model, expressed as , where is the shear stress, is the dynamic yield stress, is the consistency index, is the shear rate and is the flow index [46]. Figure 2a illustrates the flow sweep and ramp tests conducted by Grosskopf et al. [24] where shear stress was plotted as a function of shear rate for fumed silica-filled PDMS matrix materials containing different weight contents of SE1700 silicone elastomer. By fitting the curves with the H–B model to the ascending shear rate ramp data (the open symbols in Fig. 2a), the static yield stress values were calculated. Similarly, the dynamic yield stress values were calculated by fitting the H–B model to the descending shear rate ramp data, represented by the closed symbols in Fig. 2a. For simple (non-thixotropic) yield stress fluids, the static and dynamic yield stress are the same whereas these stresses are different for thixotropic yield stress fluids [47, 48].

Fig. 2.

Methods used in prior studies to determine rheological properties of supporting matrix. a, b Methods to determine yield stress. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [24]. Copyright (2018) ACS. a Flow sweep and ramp tests where shear stress is plotted as a function of shear rate for fumed silica-filled PDMS matrix materials containing different SE1700 (wt%) silicone elastomer. Yield stress values can be calculated by fitting the curves with the Herschel–Bulkley model. b Oscillatory stress sweep test where G′ and G″ moduli are plotted as a function of oscillatory stress for fumed silica-filled PDMS matrix materials containing different SE1700 (wt%) silicone elastomer at a frequency of 1 Hz. The red dots indicated the G′G″ crossover points which give the yield stress values. c–g Methods to determine the thixotropy of supporting matrix, c experimental setup of particle image velocimetry (PIV) (left) and velocity flow fields of supporting matrix obtained from PIV (middle). The results came from a supporting matrix composed of Sylgard 184 and SE 1700 (contains 20 wt% fumed silica) with 50 wt% SE 1700 (Od = 0.8). Shear rate field for 50 wt% SE 1700 matrix with a nozzle diameter d = 0.52 mm and print speed U = 1.5 mm/s (right). The gray circle in the middle represents the nozzle, while the arrow indicates the moving direction. W represents the maximum disturbed distance on both sides of the nozzle. L represents the maximum disturbed distance in front of the nozzle. The magnitude of the shear rate is displayed by a color scale, which suggests the yielded region. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [24]. Copyright (2018) ACS. d Shear rate over time after dropping the applied stress from 100 Pa to 1/10 of yield stress. The results of four types of commercially available microgels including Carbopol Ultrez 20 (0.1 wt%), Carbopol 980-NF (0.1 wt%), Carbopol ETD 2020 (0.2 wt%), and Pemulen TR-2NF (0.6 wt%) were demonstrated. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [43]. Copyright (2018) Elsevier. e Shear modulus over time, cyclic transition between 1 and 200% (shaded) strain at 6.28 rad/s. Gellan fluid gels (0.5% w/v, 0.5% w/v with 0.1% w/v CaCl2·2H2O, 1.0% w/v) were assessed. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [44]. Copyright (2019) ACS. f, g Shear stress over shear rate, the thixotropic index is calculated from the area between shear ramp up and shear ramp-down curves. Laponite nanoclay suspension with a wide range of concentration (from 1 to 4.5% w/v) were evaluated. The optimal concentration chosen (2.5% w/v) was highlighted in g. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [52]. Copyright (2018) Elsevier

The second method involves a dynamic oscillatory stress sweep test that subjects the supporting matrix to small amplitude oscillatory shear stress [24, 49]. The yield stress is identified from the crossover point of storage modulus (G′)-stress and loss modulus (G″)-stress curves, indicating the transition of the supporting matrix from solid-like (elastic) behavior to fluid-like (viscous) behavior [50]. As shown in Fig. 2b, the G′ and G″ moduli are plotted as a function of oscillatory stress for fumed silica-filled PDMS matrix materials containing different SE1700 silicone at a frequency of 1 Hz. The red dashed lines in the figure indicated the crossover point of the G′ and G″ stress curves which provided the yield stress value of each supporting matrix [24]. However, the yield stress values obtained from this method are usually higher than static or dynamic yield stress values as the material has already yielded in order to observe the increase in loss modulus G″ during the measurement. Thus, the first method with H–B fit provides a more reliable yield stress value. Nevertheless, for a thixotropic yield stress fluid, the yield stress values obtained from the second method are close to the static yield stress obtained from the first method in the ascending shear rate ramp test [45]. Moreover, storage modulus (G′)-stress and loss modulus (G″)-stress curves also provide the shear modulus that can be used to characterize the strength and rigidity of the viscoelastic supporting matrix, eventually matched with those of an ink material. The yield stress of the supporting matrix also needs to be carefully tuned to ensure compatibility with the printing materials. This will be further elaborated in the later section on the material matching of supporting materials and printing inks.

Oldroyd number and thixotropy

The Oldroyd number () is a dimensionless quantity considering both the rheological properties of supporting matrix and 3D printing parameters. It is defined as , where is the yield stress, is the consistency index, is the flow index, is the nozzle outer diameter, and is the nozzle translation speed. Thus far, there is only one publication that examined the significance of in freeform 3D printing [24]. The determines the size of the yielded fluid area in the viscoplastic matrix during nozzle movement, which is crucial to freeform 3D printing. A large yielded region surrounding the nozzle may interfere with the adjacent deposited ink filament and eventually destroy the whole structure. Bhattacharjee et al. [21] combined their freeform 3D printing system with a fluorescence microscope, to record the movement of fluorescent microparticles in the supporting matrix during nozzle translation, as shown in Fig. 2c. Velocity flow and shear rate fields of supporting matrix can be obtained by analyzing particle image velocimetry (PIV), which directly observes the deformation in the plane of the nozzle tip. An example of the velocity and shear rate field map within the supporting matrix in the plane of the nozzle tip is presented in Fig. 2c. Particularly, the gray circle in the middle represents the nozzle, while the arrow indicates the moving direction. The magnitude of the shear rate is displayed by a color scale, which suggests the yielded region. According to the shear rate field map, two high shear rate vorticities appear at the side of the nozzle perpendicular to the nozzle translating direction. Two key parameters, W (maximum disturbed distance on both sides of the nozzle) and L (maximum disturbed distance in front of the nozzle), were used to quantify the yielded region [24]. Based on the test results of supporting matrices with different , it was concluded that a high helps to reduce the yielded region around the nozzle, which preserves printed ink from the yielded matrix. Thus, can be one of key rheological parameters that explains viscoplastic behavior of the supporting matrix around the nozzle tip.

Thixotropy is generally defined as a time-dependent viscosity change, induced by flow [51]. For freeform 3D printing, it refers to the recovery of supporting matrix upon removal of the applied shear stress by the movement of the nozzle tip [24, 26, 42]. Ideally, the restructuration of a supporting matrix material immediately happens after nozzle translation, trapping the extruded ink at the designed position and shape of the ink. Hence, the time scale of the supporting matrix recovery, i.e. thixotropic time, is important for a successful freeform 3D printing [25, 27, 43, 52]. Such thixotropic properties depend on the supporting matrix concentration [52] and physicochemical conditions [26], yet being insensitive to nozzle translation speed [21]. Several methods have been used to evaluate the thixotropic behavior of supporting materials as seen in Fig. 2c–g. As shown in Fig. 2c, velocity flow and shear rate fields of supporting matrix from PIV were used to measure the time when the yielded region recovers [21]. Similar approaches to determine the thixotropic time of supporting matrices were also reported by other researchers [26, 53]. On the other hand, O’Bryan et al. [42, 43] applied a shear stress higher than yield stress to four microgel-based supporting matrices and subsequently decreased it to be lower than the yield stress, obtaining normalized shear rates as a function of time (Fig. 2d). The thixotropic time of each supporting matrix was determined when a shear rate was decreased to zero. All four systems exhibited a thixotropic time in the order of 1 s.

Alternatively, Jin et al. [25] recorded the viscosity change of fumed silica suspension after decreasing a shear rate from 10 to 0.01 s−1. The viscosity dramatically increased from 103–104 Pa s (depending on the concentration) to 106–107 Pa s in only 0.2 s, suggesting that the fumed silica supporting matrix was capable of reconstructing its microstructure in a short time. The recovery of the supporting matrix was also assessed by the cyclic transition of high (200–400%) and low (~ 1%) strain regimes. The storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) over time were used to demonstrate the material recovery and thixotropy [44, 54]. Figure 2e shows the G′ and G″ of three gellan fluid gel supporting matrices depending on applied high and low shear strains, indicating the reversible transition between solid (low strain) and liquid (high strain) behavior for all matrices. The moduli of three matrices rapidly reached equilibrium values after applied strain changed, implying a sign of fast recovery and short thixotropic time. The thixotropic index can also be calculated from the area between shear ramp-up and shear ramp-down hysteresis curves [52]. As shown in Fig. 2f, shear stress was first measured as a function of shear rate for nanoclay suspensions with various Laponite concentrations from 1.0 w/v% to 4.5 w/v% during the shear ramp-up (shear rate increased from 1 to 200 s−1) and shear ramp-down (shear rate decreased from 200 to 1 s−1) cycle. The thixotropy index of each suspension was calculated from the chosen area of its hysteresis curve at a shear rate of 50 s−1, as indicated with the dashed black box in Fig. 2f. The nanoclay suspensions with 2.5–3 w/v% show thixotropy index values of 1000–2000, which is ideal for freeform 3D printing of silk fibroin inks (Fig. 2g).

Material matching with printing ink systems

In freeform 3D printing systems, material matching between supporting matrices and printing inks is of paramount importance. Four types of instabilities can be encountered during the deposition of printing materials within the supporting matrices: (1) Reynold’s instability, (2) gravitational instability, (3) Rayleigh–Plateau instability, and (4) Crevices formation. Reynold’s instability is related to both the viscosity of the printing ink and the inertial forces induced by the translation speed of the printing nozzle. Since low viscosity materials are used in freeform 3D printing systems, the induced inertia forces within the supporting matrix overtake the viscous force of the printing ink when the nozzle translational speed is high. The dominant inertia forces cause Reynold’s instability such as recirculating wakes of the nozzles, intermixing of the supporting matrices and printing materials, and formation of crevices. To avoid instability, the dynamics of inertia forces and viscous forces can be tuned using Reynold’s number, defined as where and refers to the density and viscosity of the printing inks respectively, is the nozzle translational speed, is the diameter of the cylindrical nozzle. LeBlanc et al. [55] investigated the implications of high-speed printing on Reynolds’ instability and demonstrated that the upper limit of printing speed can be set in the range of Re < 17 by adjusting the viscosity of the printed inks, preventing the transition from stable to unstable flow regime. Comparable results were also reported by other research groups [56, 57], where confirmed recirculations of wakes began occurring at Reynolds number around 10–15. Furthermore, Grosskopf et al. [24] revealed that the translating nozzle caused dragging of the printed ink and displacement of the printed structure within the supporting matrix, when the shear elastic modulus of the printed material is larger than that of the supporting matrix or when the yield stress of the supporting matrix is much lower than the viscous stresses.

Gravitational instability arises from the sagging of printed inks due to gravitational forces. Although gravitational instabilities have been alleviated by printing in supporting matrices during freeform 3D printing, the material density of printed inks and supporting matrices have to be balanced to prevent destabilizing buoyancy forces so that deposited material would not sag after several layers of printing. On the other hand, using a supporting matrix with finite yield stress can reduce the limitations on density matching. O’Bryan et al. [27] described that by using a viscoplastic supporting matrix with a sufficiently large yield stress, gravitational instability can be avoided according to the relationship between the resultant gravitational force of the printed material and the yielding stress of the supporting matrix, expressed by , where is the density difference between the printed ink and supporting matrix, is the volume of the printed structure, is gravitational acceleration, is the yield stress of the supporting matrix and is the hydrodynamic surface area. Indeed, the yield stress of the supporting matrix must be high enough to resist the gravitational force of the ink [21, 26, 27, 41].

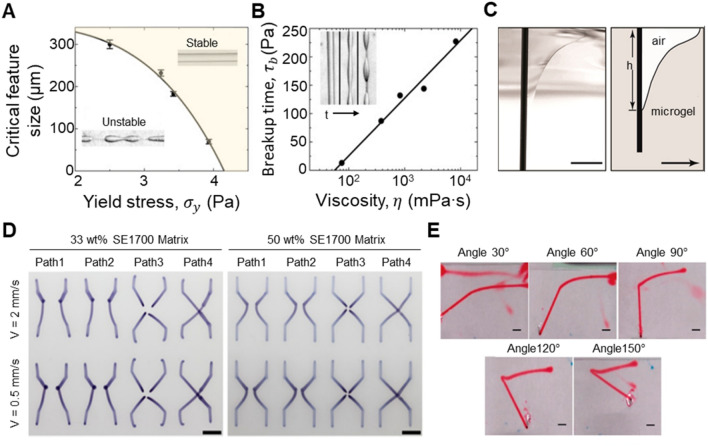

In freeform 3D printing systems, the immiscibility of the supporting matrix and printing ink is mandatory to prevent the intermixing of those two materials. However, the interfacial force or surface tension stress at the interface of the two materials create interfacial instability. Rayleigh–Plateau instability refers to the breaking up of printed structures into droplets due to the imbalance between the interfacial force/surface tension and the yield stress of the supporting matrix. This happens particularly in a printing system consisting of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic materials due to high interfacial tension [25, 42]. In fact, this effect becomes negligible when both ink and supporting matrix materials are hydrophilic [41]. Pairam et al. [58, 59] proved that breakages of printed structures in a viscoplastic material can be prevented by ensuring the surface tension or interfacial force is lower than the yield stress of the supporting matrix. As seen in Fig. 3a, the critical printable feature size in which hydrophobic silicone oil remained stable was decreased by increasing the yield stress of the hydrophilic organogel supporting matrix [42]. Therefore, by tuning the yield stress of the supporting matrix, the minimum printable dimension and geometry with good structural stability can be modulated according to the relationship, , where is the minimum printable and stable feature size, is the surface or interfacial tension between the printed ink and the supporting matrix, and is the yield stress of the supporting matrix [27, 42, 58–60]. However, breaking-up of a printed structure is also dependent on the viscosity of the ink when printing occurs below minimum printable feature size (Fig. 3b) [42]. Furthermore, a few publications [24, 39] validate that the breakages, fragmenting, and beading of printed structures are attributed to the much lower shear elastic modulus of the ink material compared to that of the supporting matrix.

Fig. 3.

Effects of instabilities on printed structures during freeform 3D printing. a, b Rayleigh–Plateau instability. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [42]. Copyright (2017) AAAS. a Minimum printable feature size of silicone oil that would remain stable was affected by the yield stress of the organogel supporting matrix. Increasing the yield stress of organogel decreased the minimum printable stable feature size. b Time taken for printed feature below minimum size to break up was influenced by the viscosity of the silicone ink. Break-up time could be elongated by increasing the viscosity of the ink. c Crevices formation from the wake of the nozzle during high translational speed in a liquid-like solid (LLS) medium made of Carbopol ETD 2020. Scale bar: 10 mm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [55]. Copyright (2016) ACS. d Varying supporting matrix (SE1700-Slygard184-fumed silica) compositions and different printing paths affected print fidelity, resulting in the displacement of Pluronic F127 ink during printing in certain conditions. Scale bars: 3 mm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [24]. Copyright (2018) ACS. e Distorted printing of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM)-based pre-gel ink in carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC aqueous) viscous liquid where designed sharp angles became rounded during printing when printing conditions are not optimized. Scale bars: 2 mm. Adapted from Ref. [74]

Crevices are formed in the wake of the nozzle when nozzle translational speed is zero (static crevice formation) or when printing at high speed but the reflow of the supporting materials in the wake of the nozzle is slow (dynamic crevices formation). These crevices formations were reported by several groups [20, 24, 39]. An example is shown in Fig. 3c, where air pocket formation was found from the wake of a nozzle at a high translational speed in a liquid-like solid (LLS) medium made of Carbopol ETD 2020 [55]. O’Bryan et al. [27] explained this phenomenon using the concept of two competing forces, the hydrostatic pressure that drives the reflow of the supporting matrix and the viscous stresses (for dynamic crevices formation) and yield stress (for static crevices formation) that resists the flow of supporting matrix. When the yield stress of the supporting matrix is larger than induced hydrostatic stress, the crevasse will not be recovered, eventually leading to failure of printing [21, 40, 55]. To prevent dynamic crevices formation, the printing speed should be set according to the relationship, , where and refers to the density and viscosity of the supporting matrix respectively, is the gravitational acceleration and is the submerged depth of the nozzle. On the other hand, to prevent static crevice formation, the yield stress of the supporting material should be sufficiently lower than induced hydrostatic pressure at a printing depth , given by [27]. An additional concern of a high-yield-stress supporting matrix is bending of long needles [31].

In summary, during freeform 3D printing, the four representative instabilities of a printed structure are largely influenced by mechanical interaction between a supporting matrix and a printing ink. Thus, material matching between the two components is essential to achieve good printing resolution, precision, and consistency. As shown in Fig. 3d, supporting matrix compositions (SE1700-Slygard184-fumed silica) and printing paths affect print fidelity, causing displacement of the Pluronic F127 ink during printing at the given printing conditions. Figure 3e displays significant distortion of printed structures made of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM)-based pre-gel inside the carboxymethyl cellulose viscous fluid (CMCaq), where the sharp edge of a bent line was rounded depending on the bending angle, implying non-optimal printing conditions. Figure 3d, e clearly exhibit common printing defects observed during freeform 3D printing, which should be eliminated through a better material matching between supporting matrix and ink materials. As a rule of thumb, shear elastic modulus and yield stress of the printing inks are recommended to be approximately an order of magnitude higher than those of the supporting matrix in order to achieve stable and decent printability [24, 39].

Material systems

At the present state-of-art, there are at least 23 types of supporting matrix systems reported for freeform 3D printing. Here, we classified these matrix material systems into three major categories (see Table 2), microparticle-dispersed slurry system, thixotropic polymer solution, and mineral nanoparticle suspension. This section explains the three types of supporting matrix systems in terms of their constitutive materials and related rheological behavior.

Table 2.

Summary of prior studies on the different types of supporting matrix system used for freeform 3D printing

| Supporting matrix system | Materials | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Microparticle-dispersed slurry system | ||

| Microparticles produced by bottom-up approaches (e.g., encapsulation or self-assembly) | Carbopol (commercially available) | [21, 23, 31, 40, 61–64] |

| PTFE microparticles (commercially available) | [49] | |

| Alginate | [65–67] | |

| Organ building blocks (iPSCs derived organoids) in ECM solution | [33] | |

| Pluronic F127 | [20, 68, 69] | |

| Self-assembled SEP-SEBS micro-organogels | [42] | |

| Microparticles produced by top-down approach from bulk gels | Gelatin | [22, 36, 65, 73, 77] |

| Gellan fluid gel | [44] | |

| Agarose slurry | [72] | |

| OMA microgel slurry | [38] | |

| Alginate/Xanthan gum/CaCO3 | [34] | |

| Thixotropic polymer solution | ||

| Modified hyaluronic acid solution | Ad40-HA and CD40-HA Ad40-MeHA and CD40-MeHA) | [29] |

| HA-BP·Ca2+ | [54] | |

| AdNor-HA and CD-HA | [30] | |

| Cellulose-based solution | CNF hydrogel matrix | [32] |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | [74] | |

| Synthetic polymer solution | PEO-based matrix phase | [76] |

| PVA-based matrix phase | [76] | |

| Hydrophobic Silicone rubber reservoir | Ecoflex elastomeric reservoir | [39] |

| Ecoflex, SortaClear | [35] | |

| NH2-functionalized PDMS | [37] | |

| Mineral nanoparticle suspension | ||

| Laponite nanoclay suspension | [26, 41, 52, 87] | |

| Fumed silica suspension (in mineral oil) | [25] | |

Microparticle-dispersed slurry systems

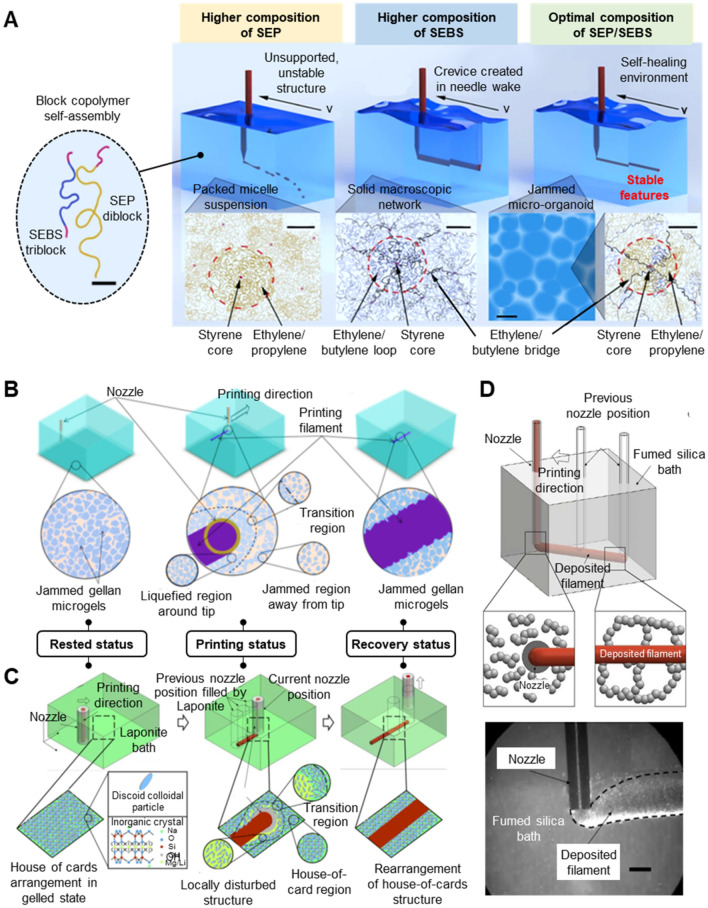

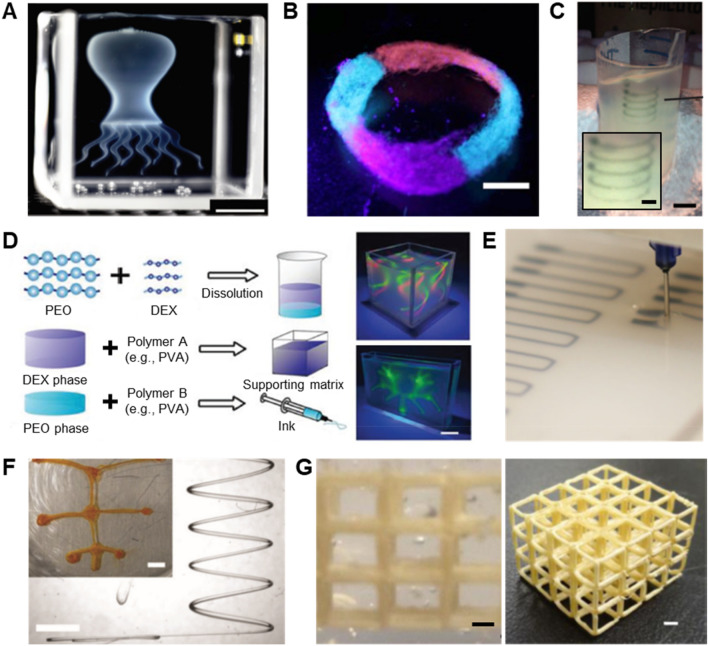

The microparticle-dispersed slurry system is one of the most popular supporting matrix systems used for freeform 3D printing. The jamming and unjamming of packed microparticles are associated with yield stress as well as thixotropic behavior, which makes the slurry fluid-like during nozzle translation and supportive to hold the printed structure as illustrated in Fig. 4a, b. The preparation method of microparticle-dispersed slurry can be simply classified as bottom-up approaches and top-down approaches.

Fig. 4.

Examples of supporting matrix systems. a Microparticles-based slurry system (bottom-up approach). Self-assembled polystyrene-block-ethylene/propylene diblock copolymer (SEP)-polystyrene-block-ethylene/butylene-block-polystyrene triblock copolymer (SEBS) micro-organogels at optimal composition can be used as freeform 3D printing supporting matrix. A higher composition of SEP demonstrates more liquid behavior and leads to unsupported, unstable structure, while a higher composition of SEBS results in poor recovery. Scale bars: 15 nm, inset: 100 nm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [42]. Copyright (2017) AAAS. b Microparticles-based slurry system (top-down approach). Gellan bulk hydrogel was pressed through a stainless-steel mesh (140 mesh, 100 μm holes) to get gellan fluid gel for freeform 3D printing. Jammed gellan gels liquefy around the translating nozzle tip and recover afterward to support the printed filament. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [44]. Copyright (2019) ACS. c, d Mineral nanoparticle suspensions system. c Laponite nanoclay suspension. Electrostatic interaction between Laponite pallets gives rise to a special ‘house-of-cards’ structure. The microstructure can be disturbed and rearranged to ensure accurate ink deposition. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [26]. Copyright (2017) ACS. d Fumed silica suspension in mineral oil. Fumed silica aggregates form a 3D network via intermolecular bonding. When nozzle movement generates shear stress, the surrounding network will break and entrap the extruded ink. A stable 3D-networked structure can reform under unstressed conditions. Scale bar: 1 mm. Reprinted permission from Ref. [25]. Copyright (2019) ACS

Microparticles produced by bottom-up approaches

Microparticles produced by bottom-up approaches include commercially available polymer microparticles (Carbopol [21, 23, 31, 40, 61–64], Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) [49]), encapsulated alginate granulates [65–67], cell-spheroid organ building blocks (OBBs) [33] and self-assembled micro micelles [Pluronic F127 [20, 68, 69], polystyrene-block-ethylene/propylene diblock copolymer (SEP)-polystyrene-block-ethylene/butylene-block-polystyrene triblock copolymer (SEBS) micro-organogels] [42].

Carbopol is commercially available polyacrylic acid (PAA) microparticles with a diameter of ~ 7 µm. Carbopol microparticles can swell in water and form a granular gel medium with ideal rheological properties to be used as a freeform 3D printing supporting matrix (Fig. 5a). The jamming and unjamming transition behavior of microgels leads to the fluidization of the granular gel medium during printing, as well as fast recovery (in the order of 1 s) to hold the printed structure [21, 43, 63]. The other advantages of the Carbopol supporting matrix are easy preparation in large volume [61, 64], thermal stability (up to 65 °C) [23], and transparency for good visualization [21, 31, 40]. Moreover, the biocompatibility of the Carbopol supporting matrix makes it a good candidate for 3D cell culture [70, 71] and bioprinting [40, 63]. Among the various species, Carbopol 940 and Carbopol ETD 2020 are most commonly applied in 3D freeform printing. The yield stress of the Carbopol supporting matrix can be tuned by several approaches. The most straightforward method is to vary the Carbopol concentration. Higher concentration results in higher yield stress [31, 40, 62]. Adjusting the pH can also tailor the rheological properties of Carbopol. For Carbopol ETD 2020, the water dispersion is initially acidic (pH around 3). At pH = 5.5, a sol–gel transformation happens, and the gel becomes usable as a supporting matrix material. At pH > 7, extensive swelling of microparticles occurs due to electrostatic repulsion of ionized carboxylic acid groups, while both yield stress and storage modulus of the Carbopol supporting matrix decrease, leading to a compromised printing resolution. Thus, Carbopol supporting matrices under the physiological condition (pH 7) are still preferred in many studies, particularly due to their suitability for cell-related works [21, 31, 40, 63]. Moreover, the rheological behavior of Carbopol is affected by ionic strength since PAA is a weak anionic polyelectrolyte. Excessive ions shield electrostatic repulsion between PAA networks, resulting in shrinkage of microparticles and liquefaction of the supporting matrix. Physiological saline solutions such as sodium chloride (NaCl) solution and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) often induce a shear-thinning effect so that they can be utilized as releasing agents for removal of the Carbopol supporting matrix [23, 40, 63, 64]. Another commercially available microparticle system used as a supporting matrix is PTFE (100 µm in diameter). Its hydrophobicity and oxygen permeability are favorable for the printing of bacteria-incorporated cellulose nanofibers [49].

Fig. 5.

Freeform 3D printing in various supporting matrix systems. a–c Printing in microparticle-dispersed slurry systems. a A thin-shell octopus printed in Carbopol. The ink is composed of photo-cross-linkable polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Scale bar: 10 mm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [21]. Copyright (2015) AAAS. b Multimaterial Mobius strip printed in Pluronic F127. The inks consist of alginate with different dyes. Scale bar: 10 mm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [69]. Copyright (2018) SAGE. c Alginate helix printed in gelatin slurry. Scale bars: 10 mm (left) 2.5 mm (right). Reprinted with permission from Ref. [22]. Copyright (2017) AAAS. d Schematics showing the formulations of an aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) by mixing poly(ethylene) (PEO) and dextran (DEX)-based polymer solutions. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [76]. Copyright (2019) Wiley–VCH. e, f Printing in a thixotropic polymer solution. e A conductive ink made of carbon conductive grease printed into an uncured Ecoflex elastomeric reservoir with a filler fluid. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [39]. Copyright (2014) Wiley–VCH. f Continuous threads of a helix and a branched structure with water and nanoparticles as the ink printed in a supporting matrix composed of silicone oil with mono-aminopropyl-terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS-NH2). Scale bar: 2 mm, inset: 0.5 cm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [37]. Copyright (2018) Wiley–VCH. g Printing in mineral nanoparticle suspension where photosensitive SU-8 resin lattice structure are printed in Laponite nanoclay suspension. Scale bars: 2 mm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [26]. Copyright (2017) ACS

Natural hydrogels can be fabricated in a form of microgels as a new type of supporting matrix system. For instance, alginate microparticles can be prepared by two methods, emulsion [65] and encapsulation [66, 67]. The emulsion method involved the mixing of alginate solution with calcium citrate suspension and dispersing the mixture into sunflower oil under constant magnetic stirring. Subsequently, glacial acetic acid was added into the oil to dissolve the calcium citrate and generate calcium ions for alginate crosslinking. The crosslinked beads were eventually mixed with alginate solution to obtain the supporting matrix for negative freeform printing. After channel printing, the matrix was transferred into NaCl solution to dissolve the beads. NaCl was then carefully exchanged with calcium chloride (CaCl2) to cure the whole structure [65]. Tan et al. [66, 67] fabricated the alginate ‘slurries’ composed of synthesized calcium alginate microgels produced via encapsulation with an average particle diameter of ~ 200 µm for positive freeform 3D printing. Despite having good heat stability, the calcium alginate beads are prone to dehydration that leads to deformation and destruction of the alginate network under high heating rate and prolonged heating. However, incorporation of glycerol as a humectant during the encapsulation process of alginate microparticles can produce alginate ‘slurries’ that are biocompatible, highly heat resistant, recyclable, reusable, and recoverable for multiple times of freeform 3D printing. On the other hand, cell-laded hydrogel microparticles can also be used for a supporting matrix. Organ building block (OBB) matrices are composed of cell aggregates and cross-linkable extracellular matrix (ECM) prepolymer gel. Embryoid bodies (EBs), cerebral organoids, or cardiac spheroids with a size of ~ 200 μm were generated based on different culturing conditions and served as ‘microparticles’ in the supporting matrix. The OBB matrix possessed an ultra-high cell density compared to all other supporting matrix systems [33].

Self-assembled micro-micelle suspension induced by the configuration of block copolymers acts as a viscoplastic fluid at ambient temperature which can be used as a freeform 3D printing supporting matrix [20, 68, 69]. As shown in Fig. 4a, Self-assembled SEP-SEBS micro-organogels at optimal composition were developed as a supporting matrix for freeform 3D printing of silicone. SEP diblock polymer micelle suspension acts as a fluid, failing to support printed structures, while unrecoverable crevice is created within SEBS triblock polymer solid network due to nozzle movement. A mixture of both at optimal ratio results in supportive and self-healing micro-oranogel supporting matrix for freeform 3D printing [42]. On the other hand, Pluronic F127 is a triblock polymer that consists of poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) and poly(propylene oxide) (PPO). The PEO-PPO-PEO configuration enables Pluronic F127 to form micro micelles consisting of hydrophobic PPO core and hydrophilic PEO corona upon reaching the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of ~ 21 w/w%. A supporting matrix with a higher concentration of Pluronic F127 is more supportive but suffers from poor recovery. Thus, a Pluronic F127 solution with a concentration slightly lower than CMC was applied upon the supporting matrix [20] (Fig. 5b). Moreover, the rheological behavior of self-assembled micelle suspension is temperature-dependent. Only when the temperature is higher than the critical micelle temperature (CMT) of ~ 10 °C, Pluronic F127 forms micelles due to hydrophobic interactions of PPO segments. Hence, Pluronic F127 supporting matrix becomes liquefied and easily removed when the temperature is decreased below the CMT [68]. Photo-cross-linkable functional groups can be conjugated to Plutonic F127 for a curable supporting matrix of negative freeform 3D printing [20].

Microparticles produced by top-down approaches

Microparticles produced by top-down approaches are usually prepared by the blending of bulk hydrogels. Irregular microparticles are then centrifuged and reimmersed in a medium to get a suspension. Gelatin support bath, gellan fluid gel, agarose slurry, oxidized and methacrylated alginate (OMA) microgel slurry, and alginate/Xanthan gum/CaCO3 support medium were all produced with this protocol [44]. An example of a supporting matrix system composed of microparticles produced by the top-down approach is illustrated in Fig. 4b. Gellan bulk hydrogel was particularized through a stainless-steel mesh (140 mesh, 100 μm holes) to obtain gellan fluid gel. Jammed gellan gels liquefy around the translating nozzle tip and recover afterward to support the printed filament [44].

Likewise, gelatin slurry support bath was first developed by Hinton et al. [22] (Fig. 5c). A bulk gelatin gel was broken into irregular particles by a commercial blender. The gelatin particles subsequently were dispersed in water after centrifugation and washing, forming the viscoplastic gelatin slurry [22]. Due to the thermo-reversible physical crosslinking, gelatin slurry can be easily removed by increasing the ambient temperature up to 37 °C. On the other aspect, the thermo-instability of gelatin slurry also restricts its applicability for printing inks that require either heat-assisted curing or undergo exothermal solidification processes [72]. As a natural polymer, gelatin support bath is a good choice for bioprinting or constructing tissue engineering scaffolds due to its great biocompatibility, with minimal cytotoxicity of gelatin residuals after releasing the printed part from the supporting matrix [22]. By varying the blending time, the average size of gelatin microparticles was tuned. Sufficiently long blending time reduced the gelatin particle size, producing a higher printing resolution [22]. However, extensive blending may liquefy gelatin particles due to heat generation [72]. Another way to tune the rheological behavior of gelatin slurry is by varying the concentration of gelatin microparticles. Lower concentrations of gelatin microparticles reduce storage modulus and yield stress of the gelatin slurry [73]. Also, incorporation of precursors in the gelatin slurry can induce solidification of printed inks [22, 73], and in situ precipitation of inorganic nanoparticles on the surface of a printed scaffold [36]. Gelatin slurry can also act as a supporting matrix for negative freeform 3D printing by adding gelatin solution for the temperature-induced physical gelation of the slurry [65].

Thixotropic polymer solution

Besides microparticle-based slurries, polymer solutions with thixotropic behavior also meet the criteria required of a freeform 3D printing supporting matrix. We categorized those thixotropic polymer solutions into modified hyaluronic acid (HA) solution, cellulose-based solution, aqueous two-phase (ATP) polymer solution, and hydrophobic silicone rubber reservoir based on their major polymeric constituents.

Modified hyaluronic acid solution

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a highly hydrophilic and biocompatible nature polymer, that can easily conjugate with extra functional groups and be used for various applications including a supporting matrix for freeform 3D printing. Highley et al. [29, 30] conjugated HA with either adamantane (AD) or β-cyclodextrin (CD), forming Ad-HA and CD-HA. The noncovalent intermolecular guest–host bonds between Ad-HA and CD-HA construct supramolecular HA assemblies. Due to the reversibility of the noncovalent bonds, viscoplastic Ad-HA and CD-HA mixtures can be applied as both ink and supporting matrix for 3D printing. Photo-cross-linkable Ad-HA and CD-HA mixtures through further conjugation with methacrylate or norbornene groups can be used for a supporting matrix of negative freeform 3D printing [29, 30]. Furthermore, bisphosphonate-functionalized HA (HA-BP) can serve as a support matrix for HA ink writing with the existence of calcium ions [54].

Cellulose-based solution

Cellulose nanofiber (CNF) solution possesses a gel-like behavior due to its highly entangled microstructure. Shin et al. [32] used a CNF solution as the supporting matrix and deposited fugitive petroleum-jelly as the ink. The CNF supporting matrix with a higher CNF concentration exhibited higher viscosity and yield stress than that with a lower CNF concentration, thus rheological properties of CNF supporting matrices can be matched with those of various petroleum-jelly inks in terms of CNF concentrations. After dehydration, the CNF supporting matrix formed a transparent paper film while the internal printed structure of petroleum-jelly remained intact [32]. Moreover, carboxymethyl cellulose was used for the supporting matrix of freeform 3D printing using temperature-sensitive NIPAM-alginate inks [74].

Aqueous two-phase (ATP) polymer solution

The aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) is a liquid–liquid platform used for the fabrication of 3D-structured biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids [75]. Recently, Luo et al. [76] utilized the poly(ethylene) (PEO)/ dextran (DEX)-based ATPS for 3D printing, obtaining all-aqueous 3D architecture (Fig. 5d). When two immiscible PEO and DEX polymer solutions are mixed, the steric exclusion between the two polymers induces phase separation, creating the bi-phasic system. The higher-density and more viscous DEX-rich phase at the bottom layer was used as the ink, while the lower-density and less viscous PEO-rich phase at the top layer was used as the supporting matrix. When DEX ink was printed within the PEO-based supporting matrix, low interfacial tension associated with thermodynamically induced phase separation stabilizes the printing structure, allowing continuous and precise deposition of the ink at high resolution. In addition, the two liquid phases of the APTS can be transformed into gels by incorporation of cross-linkable polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) into either the supporting matrix or the ink material.

Hydrophobic silicone rubber reservoir

A few freeform 3D printing systems using supporting matrices composed of hydrophobic silicone rubber reservoirs were developed for various purposes and applications. To reduce multiple processing steps that constrained the sensing capabilities of soft somatosensitive actuators and strain sensors, Lewis and co-workers [35, 39] developed a freeform printing system enabling direct printing into a soft elastomeric matrix that possesses high extensibility after curing, making it suitable for soft robotics and soft sensing applications. Their system named as embedded 3D printing (E3DP or EM3DP) is a three-component functional freeform printing system, comprising a fugitive conductive ink (e.g., carbon conductive grease), the silicone elastomeric supporting matrix composed of commercially available silicone elastomer Ecoflex, and a filler liquid made up of the same Ecoflex with a thinning agent (see Fig. 5e). The important considerations for this EM3DP system include: (1) the optimal ratio between thickening and thinning agents in the uncured elastomer reservoir such that the rheological properties are suitable for printing in the pre-cured state but will not affect the ultimate curing process; (2) Newtonian behavior of the filler liquid so that the filler liquid can readily fill the crevices due to the translating nozzle, and (3) the chemical similarity of the elastomer reservoir and the filler liquid such that both components can be co-cured to form a monolithic part without creating internal interfaces in the cured elastomeric matrix.

An all-liquid system that allows repeated reconfiguration was created by Forth et al. [37] using a hydrophobic silicone rubber reservoir as the supporting matrix. This system uses hydrophilic inks, composed of carboxylic acid-functionalized nanoparticles dispersed in water, printed in hydrophobic silicone oil containing mono-aminopropyl-terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS-NH2), as shown in Fig. 5f. The electrostatic binding between the nanoparticles and PMDS-NH2 at the oil–water interface induces elastic assemblies of nanoparticle surfactants (NPSs) that stabilize nonequilibrium liquid shapes, thereby retaining the shape and structure of the printed liquid within a long tunable lifetime up to several months. The structures could be further stabilized by polymerization or crosslinking of the NPS assemblies with multi-functional polymers. The key advantage of this system includes its responsive behavior (e.g., reconfiguration or re-compartmentalization of a printed structure) to an applied external stimulus (e.g., chemical cues). Thus, the printed structures can be repeatedly reconfigured within a reasonable time, making it suitable for applications in all-liquid electronics, vessels for biphasic chemical synthesis and chemical separations, and novel medium for the encapsulation of cells and active matter. This work proved the potential of freeform printing systems for creating a new class of biomimetic, reconfigurable, and responsive materials composed of two liquid phases with stable interfaces.

Mineral nanoparticle suspension

Mineral nanoparticles such as laponite and fumed silica are capable of forming microstructures when they are suspended in a liquid. More importantly, the microstructure will collapse and reform under different shear conditions, allowing mineral nanoparticle suspension to be applicable in freeform 3D printing as a supporting matrix (Fig. 4c, d).

Laponite is a synthetic clay material with a chemical formula of Na0.7Si8Mg5.5Li0.3O20(OH)4. Each nanoclay particle is in a platelet shape with a diameter of ~ 25 nm and a thickness of ~ 1 nm. When the nanoplatelets are dispersed in water, the top and bottom faces become negatively charged due to Na+ dissociation, while the edge becomes positively charged due to the presence of amphoteric groups (e.g., Mg–OH, Li–OH or Si–OH). The face-to-edge electrostatic interaction results in a reversible ‘house of cards’ arrangements, which makes Laponite suspension a yield-stress colloid [41]. In addition, nanoclay suspension can quickly recover to its steady colloidal state after yielding owing to its thixotropic behavior [52]. In addition to these key rheological characteristics for supporting matrix materials, Laponite nanoclay suspension also possesses thermal stability and UV transparency. Three types of Laponite including Laponite RD, Laponite XLG, and Laponite EP have been used in freeform 3D printing. Among the three, organically-modified Laponite EP has the highest biocompatibility due to moderate ionization, thus is commonly used for bioprinting. Meanwhile, modified Laponite becomes less ion-sensitive, allowing the incorporation of extra ions for further functionalization of the system [26]. Figure 4c shows the mechanism behind this supporting matrix system where the electrostatic interaction between Laponite pallets gives rise to a special ‘house-of-cards’ structure. The microstructure can be disturbed and rearranged to ensure accurate ink deposition. The concentration of Laponite significantly influences the rheological properties of the suspension, thus the suspension with a higher Laponite concentration exhibits higher yield stress, storage moduli, and loss moduli [41]. The Laponite suspension becomes less sensitive to the nozzle size and movement during printing as the Laponite concentration increases [26]. Moreover, increasing temperature to 37 °C does not alter the rheological behavior of Laponite nanoclay suspension, allowing freeform 3D printing of cell-incorporated bioink [41]. Figure 5g shows a photosensitive SU-8 resin lattice structure printed and cured in a Laponite nanoclay suspension. Laponite nanoclays suspended in a polymer solution can also be used as a supporting matrix. Rodriguez et al. [52] successfully mixed poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) into the Laponite nanoclay supporting matrix to induce the self-assembly of silk ink.

Fumed silica-mineral oil suspension is a transparent supporting matrix that can be used for printing of hydrophobic materials including PDMS, SU-8, and epoxy-based conductive ink [25]. The intermolecular bonding of silica agglomerates forms a physically breakable 3D network under a stressed condition. Figure 4d shows the working mechanism of the fumed silica-mineral oil suspension for freeform 3D printing. When nozzle movement generates shear stress, the surrounding silica network around the nozzle will be broken, entrapping the extruded ink at the position. A stable 3D-networked structure can be reformed once the shear stress induced by the nozzle movement disappears. It is noteworthy that the fumed silica-mineral oil suspension is chemically stable, ecologically safe, and recyclable for multiple 3D printing tasks.

Freeform 3D printing systems for biomedical applications

The development of freeform 3D printing systems represents a major step forward for biomedical engineering as most materials used in the biomedical field involves soft matters such as biomaterials, living cells, biopolymers, silicones, that were previously difficult to print with conventional AM systems. Freeform 3D printing systems make it possible for researchers to print these low viscosity materials and explore a broader range of soft matters for various applications. The detailed range of printed products produced via various freeform 3D printing systems is listed in Table 3. With the gaining popularity of freeform 3D printing systems, there were increasing publications in several fields of applications including tissue engineering, vascularisation, microfluidics, 4D printing, and elastomer fabrication. Recent advances in these fields will be discussed in this section.

Table 3.

Summary of prior studies on the printed products produced with various ink materials and supporting matrix in different freeform 3D printing systems

| Printing systems | Supporting matrix | Ink material | Printed objects/applications | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Carbopol | Photocrosslinkable PVA, collagen with cells | Thin shell model octopus, jellyfish, Russian dolls, hierarchically branched tubular networks | [21] |

| Sylgard 184 | Vase, helix, tube and perfusable bifurcation | [23] | ||

| Alginate-gelatin ink with cells | Y-shaped cellular construct | [40] | ||

| Urethane plastic, urethane rubber | Ball-joint cylinder, variable surface, and lattice | [61] | ||

| EGaIn liquid metal | 12 animals of Chinese zodiac, heart-shaped structural electronics | [62] | ||

| GelMA-alginate ink with cells | 3D bifurcation structure | [63] | ||

| Photocrosslinkable bioelastomer | Microtubes | [64] | ||

| Gelatin | Hydrogels (alginate, fibrinogen, collagen), ECM ink with cells | Complex biological structures (femur, arterial tree, heart, brain) | [22] | |

| GelMA/PEDOT:PPS ink with cells | Buckyball and ventricle structure | [73] | ||

| Alginate-hyaluronic acid | Scaffold and femur structure | [77] | ||

| Pluronic F127 | F127-DMA (with GO or CNT) | Inverted cone and scaffold | [68] | |

| Alginate | Multi-material star shape, MIT letters, Klein bottle, and Mobius strip | [69] | ||

| Laponite nanoclay suspension | Alginate-gelatin ink with cells | Cellular vascular construct | [41] | |

| Alginate, gelatin-alginate with cells, SU-8 | Y-shape tube, bone, brain, microvascular network, and lattice structure | [26] | ||

| Silk fibroin | Suspended hydrogel arrays, vase, scaffold, and helix | [52, 87] | ||

| Ad40-HA and CD40-HA | Ad25-MeHA and CD25-MeHA | Continuous spiral and pyramidal shape | [29] | |

| HA-BP·Ca2+ | Am-HA-BP·Ca2+ | 3D tube-like structure | [54] | |

| Self-assembled SEP-SEBS micro-organogels | UV-curing silicone elastomer (UV Electro 225) | Model trachea implant, scaffold, perfusable network and pump with encapsulated valves | [42] | |

| Gellan fluid gel | Gelatin/alginate, PEGDA/gellan, alginate ink | Lattice, spiral cone, branching tube | [44] | |

| Agarose slurry | Alginate, GelMA with cells | Scaffold, honeycomb construct, helix | [72] | |

| PTFE microparticles | CNF hydrogel ink with bacteria | Coil, connected ring, tetrahedron, stacked lattice, sandglass, cuboid, hollow sphere, and tube | [49] | |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | NIPAM-alginate, AMM-alginate | Circle, T-shape, spring | [74] | |

| Fumed silica suspension (in mineral oil) | Sylgard 184, Su-8, epoxy-based conductive ink | Fluidic microchip, octopus, gear, inductor, and battery anode/cathode set | [25] | |

| Alginate/Xanthan gum/CaCO3 | Omentum gel with cells (personalized bioink), gelatin (sacrificial ink) | Cardiac patches, multilayer crisscross structure, hand shape, thick vascularized cardiac tissue | [34] | |

| PEO-based matrix phase | PVA-based ink phase | Spring, tornado, barbell, branched networks | [76] | |

| Negative | Carbopol and PEGDA | Silicon oil emulsion | Multi-internal surface structures, a liver model with blood vessels, brain model | [31] |

| Gelatin, alginate | Xanthan-gum | Microfluidics embedded in hydrogel matrices | [65] | |

| Pluronic F127-DA | Pluronic F127 | 3D microvascular networks | [20] | |

| Ad40-MeHA and CD40-MeHA | Ad25-HA and CD25-HA | Channel structure | [29] | |

| AdNor-HA and CD-HA | Ad-HA and CD-HA | Straight, stenosis and spiral microchannels | [30] | |

| CNF hydrogel matrix | Petroleum-jelly-based ink | Triangular pyramid, sphere, helix, flexible paper microfluidics with multilayered channels | [32] | |

| Organ building blocks (iPSCs derived organoids), ECM solution | Sacrificial gelatin ink | Perfusable EB and cardiac tissue | [33] | |

| PVA-based matrix phase | PEO-based ink phase | Gel with a hollow structure | [76] | |

| Functional | Ecoflex elastomeric reservoir | Carbon conductive grease | Strain sensors within stretchable elastomers | [39] |

| Ecoflex, SortaClear | Sensor ink (fumed silica in EMIM-ES), Fugitive ink (Pluronic F127) | Curvature, inflation, and contact sensor for soft robotic grippers with somatosensory feedback | [35] | |

| Gelatin + calcium ions | GMHA/alginate ink + phosphate ions | Nanocomposite hydrogel scaffold | [36] | |

| OMA microgel slurry | hMSCs cell-only bioinks | Bone or cartilage-like tissues | [38] | |

| NH2-functionalized PDMS | COOH-functionalized nanoparticle dispersion | Spiral, helix, and branched structure | [37] |

Tissue engineering scaffolds

Tissue engineering is an important field in which engineering and life sciences come together to create tissue substitutes for the regeneration and replacement of damaged, diseased, or missing tissues and organs. Recently, 3D printing has become an emerging technique for tissue engineering due to its capability to produce customized scaffolds. However, natural organs possess complex architecture with overhanging structures that are difficult to fabricate with conventional layer-by-layer printing. With the help of a supporting matrix, freeform 3D printing brought new options to this field to accomplish the printing of designs in three dimensions. In addition, a high-viscosity ink with good processability usually results in low viability during the incorporation of cells due to the harsh printing condition. The supporting matrix makes it possible to print inks with lower viscosity, improving cell viability during bioprinting.

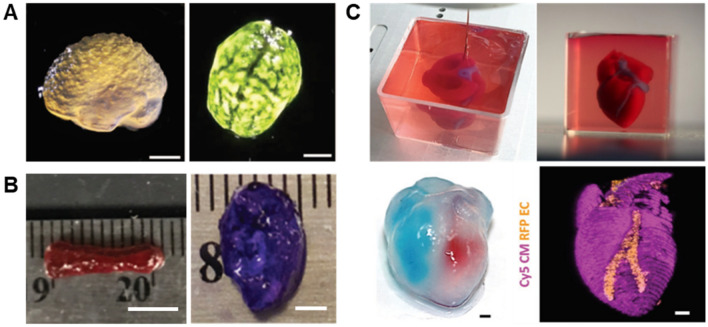

Hinton et al. [22] introduced the gelatin slurry as a support matrix and successfully fabricated complex biological structures including human femur (scaled down to ~ 35 mm length), hollow right coronary artery vascular tree, embryonic chick heart (scaled up 10 times) and human brain (scaled down to 3 cm length through the positive freeform 3D printing system with various hydrogel inks, as shown in Fig. 6a. Those biological tissue structures were obtained from various medical imaging tools (e.g., MRI) and were reconstructed for 3D printing. Particularly, the intricate morphology of the cerebral cortex folds in the printed alginate brain was precisely replicated, demonstrating that this printing system is capable of fabricating hydrogel constructs that mimic complicated biological structures [22]. Furthermore, Wang et al. [77] introduced a freeze-casting post-printing step after freeform 3D printing of the scaffolds for the incorporation of hierarchical pore structures. The printed alginate structure in the gelatin slurry was frozen overnight and lyophilized. Subsequently, the scaffold was rehydrated and released in CaCl2 solution at 37 °C. The resultant hydrogel scaffolds maintained their 3D printed structures while exhibiting the interconnected micro-pore network. This hierarchical pore structure allowed the in-growth of MDA-MB-231 cells seeded on the scaffold [77]. Composite hydrogel scaffolds were also directly fabricated by functional freeform 3D printing, reported by Chen et al. [36]. Calcium ions dissolved in the gelatin slurry were reacted with phosphate ions existing in the hyaluronic-based hydrogel ink, triggering in situ precipitation of CaP during the freeform 3D printing process. The composite hydrogel scaffolds demonstrated better cell attachment and proliferation compared to those pure hydrogel scaffolds without CaP. Moreover, by tuning the phosphate ion concentration in the ink, composite hydrogel with different CaP content can be easily obtained. The scaffold with CaP content gradient can be potentially applied to regenerate the interface between hard and soft tissue [36].

Fig. 6.

Tissue constructs fabricated by freeform 3D printing. a 3D printed alginate brain with major anatomical features. Black dye was dipped upon the structure to help visualization from the top view. Scale bars: 1 cm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [22]. Copyright (2015) AAAS. b 3D bioprinted hMSC bone-like construct with Alizarin red S staining and cartilage-like construct with Toluidine blue O staining. The cell only bioink was deposited into oxidized and methacrylated alginate (OMA) microgel. The support bath was later solidified and cultured in different mediums to let the hMSCs form tissue-like construct. Scale bar: 5 mm (left) 2 mm (right). Reprinted with permission from Ref. [38]. Copyright (2019) RSC. c Printed thick vascularized cardiac tissue within a supporting matrix composed of alginate microparticles and xanthan gum-supplemented growth medium. After releasing from supporting matrix, red and blue dyes were injected in left and right ventricles to show hollow chambers. The omentum gel was mixed with cardiomyocytes (CMs) or endothelial cells (ECs) to generate tissue-specific bioink. 3D confocal images were taken for visualization of different cells, CMs in pink and ECs in orange. Scale bars: 1 mm. Adapted from Ref. [34]

Furthermore, many researchers directly incorporated cells into 3D printing ink to form biomimetic tissue constructs. Spencer et al. [73] explored a cell-laden conductive bioink composed of photo-cross-linkable and conductive Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) with C2C12 cells. With the help of the gelatin supporting matrix, cell-laden scaffolds with complex geometry (e.g., 3D Buckyball and ventricle structures) were successfully fabricated with good fidelity. Besides, the printed GelMA/PE-DOT:PSS hydrogels were biocompatible and biodegradable in vivo, showing great potential as a scaffold for the regeneration of electroactive tissue [73]. Jeon et al. [38] deposited the human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSCs)-dispersed bioink into the oxidized and methacrylated alginate (OMA) microgel-based supporting matrix. The supporting matrix was subsequently photo-crosslinked to trap the cells for long-term culturing (4 weeks). Two types of differentiation mediums were applied for osteogenesis and chondrogenesis of encapsulated hMSCs. Figure 6b shows both bone-like and cartilage-like tissues, eventually obtained after cell condensation and differentiation [38]. Nadav et al. [34] successfully printed a scaled-down robust heart model with perfusable blood vessels, as shown in Fig. 6c. Two cellular bioinks, composed of human omentum-derived hydrogels with two cell types, were chosen for the fabrication of the heart model. The first cardiac cell-laden bioink was prepared by mixing cardiomyocytes (CMs), differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with the omentum gel for the printing of parenchymal tissue, while the second iPSC derived endothelial cells (ECs)-laden bioink that was used for the formation of blood vessels were constructed by ink incorporated with iPSC derived endothelial cells (ECs). A transparent and cell-friendly supporting matrix, consisting of alginate microparticles and xanthan gum-supplemented growth medium, retained the 3D structure of the printed heart model with high cell viability [34].

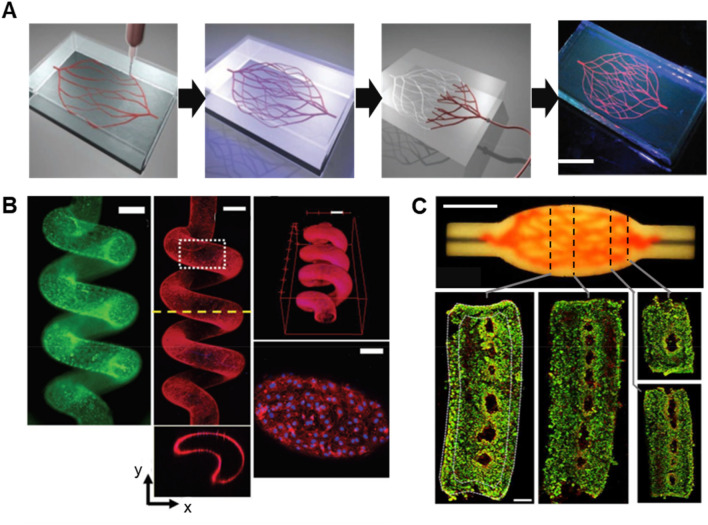

Vascularization of engineered tissues

Blood vessels play an important role in transporting oxygen and nutrients to the cells as well as removing waste from the cells. However, the incorporation of vascular channels into an engineered tissue construct remains challenging for conventional 3D printing techniques. Limitations to the printing of a hollow vascular network in an artificial tissue construct can potentially be addressed by negative freeform 3D printing which offers a new strategy to directly incorporate a microvascular network within a cell-laden matrix with high precision. Wu et al. [20] first exploited the omnidirectional printing (ODP) method to produce a 3D microvascular network embedded within a Pluronic F127 diacrylate (F127-DA) hydrogel matrix, using Pluronic F127 as a fugitive ink (Fig. 7a). Additionally, a fluid filler composed of F127-DA was placed on top of the matrix to fill up crevices created by the nozzle translation. The polymer concentrations of the ink, the matrix, and the fluid filler were optimized for matching their rheological behavior for continuous printing with good fidelity. After freeform 3D printing, the F127-DA matrix was cured under UV exposure and, subsequently, the ink was liquified and removed, forming the hollow channels. Song et al. [30] further seeded endothelial cells on the internal surface of microchannels for endogenesis. The microchannels construction process was similar to ODP. The shear-thinning fugitive hydrogel ink was composed of adamantane modified hyaluronic acid (Ad-HA) and β-cyclodextrin modified HA (CD-HA), while the photo-cross-linkable matrix was a mixture of norbornene modified Ad-HA (AdNor-HA) and CD-HA. After seeded human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were sufficiently attached to the channel surface, the culture medium was perfused through the channel for cell growth. Confocal images confirmed confluent layers of HUVECs formed throughout the whole microchannel structure (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, when the cells were exposed to angiogenic factors, significant angiogenesis sprouting was detected after 3 days of culturing.

Fig. 7.

Vascular microchannel structures constructed by freeform 3D printing. a Schematic of omnidirectional printing of 3D microvascular networks in Pluronic F127-based matrix. The fugitive ink is composed of Pluronic F127, while the supporting matrix is composed of photo-cross-linkable Pluronic F127 diacrylate (F127-DA). Scale bar: 10 mm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [20]. Copyright (2011) Wiley–VCH. b Fluorescent images of a spiral microchannel with fluorescent beads (green) and endothelial cell-seeded channel stained for CD31 (red and nucleus (blue) 2d after seeding. A mixture of adamantane modified hyaluronic acid (Ad-HA) and β-cyclodextrin modified HA (CD-HA) was used as sacrificial ink, while the photo cross-linkable matrix was composed of norbornene modified Ad-HA (AdNor-HA) and CD-HA. Scale bars: 500 μm (top), 100 μm (bottom). Reprinted with permission from Ref. [30]. Copyright (2018) Wiley–VCH. c Perfusable embryoid body (EB) tissue fabricated by sacrificial writing into functional tissue (SWIFT). The supporting matrix is composed of EB organ building blocks (OBBs) derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and extracellular matrix (ECM) prepolymer gel. The top figure showed the image of perfusable tissue with sacrificial gelatin ink (red). The bottom images are fluorescent images of LIVE/DEAD (green/red) cell viability stains at various cross-sections. Scale bars: 10 mm (top), 1 mm (bottom). Reprinted with permission from Ref. [33]. Copyright (2019) AAAS

On the other hand, Skylar-Scott et al. [33] directly used cell aggregates as the supporting matrix to build a vascularized organ-specific tissue system using the process, termed “sacrificial writing into functional tissue (SWIFT).” Patient-specific iPSCs were first cultured in microwells for the fabrication of embryoid bodies (EBs), cerebral organoids, or cardiac spheroids. The EB OBBs were subsequently mixed with ECM prepolymer gel to form the EB-ECM supporting matrix. After printing of the vascular network using the gelatin ink, the cell-laden supporting matrix was physically crosslinked while the sacrificial gelatin ink was removed. The perfusable EB tissue constructed by SWIFT was found to exhibit high cell density and good cell viability, as seen in Fig. 7c. Similarly, a cardiac tissue with septal branches was successfully fabricated using the cardiac spheroid-based matrix. SWIFT clearly demonstrated an advanced biomanufacturing method to produce perfusable organ-specific tissue constructs with high cell density that mimic the microarchitecture of native tissue systems.

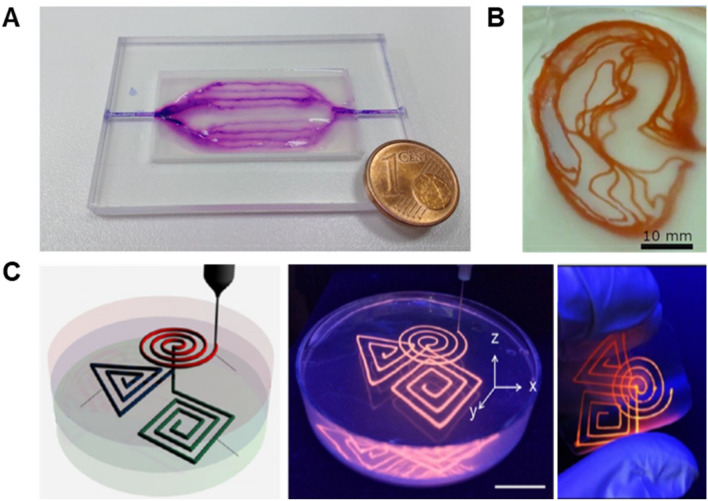

Microfluidic devices

Microfluidic devices are chips with microchannel architectures for the manipulation of fluid at the microscale. They have been actively utilized in cell biology due to their outstanding throughput for various biological assays with a low volume of liquid. Freeform 3D printing methods were actively introduced for the fabrication of microfluidic devices [32, 65]. For instance, Štumberger et al. [65] fabricated perfusable microfluidic channels embedded in hydrogel matrices as shown in Fig. 8a, b. Uncrosslinked hydrogel solution was added into hydrogel microparticles of the supporting matrix to facilitate the solidification of the supporting matrix after freeform 3D printing with the sacrificial xanthan gum ink. Both perfusable 2D branched and 3D earlobe-shaped microchannels were successfully printed [65]. Shin et al. [32] reported paper-based microfluidic devices using the negative freeform 3D printing system composed of the CNF supporting matrix and fugitive petroleum jelly ink (Fig. 8c). The average diameter of microchannels correlated with the printed ink filament was controlled by applied pressure during 3D printing. After printing, the CNF supporting matrix was dried and, subsequently, the printed petroleum jelly was removed to form the open microfluidic channels within the paper sheet. The CNF microfluidic devices were successfully applied to selective detection of heavy metal ions.

Fig. 8.