Abstract

After fertilization, the zygotic genome is activated through two phases, minor zygotic activation (ZGA) and major ZGA. Recently, it was suggested that DUX is expressed during minor ZGA and activates some genes during major ZGA. However, it has not been proven that Dux is expressed during minor ZGA and functions to activate major ZGA genes, because there are several Dux paralogs that may be expressed in zygotes instead of Dux. In this study, we found that more than a dozen Dux paralogs, as well as Dux, are expressed during minor ZGA. Overexpression of some of these genes induced increased expression of major ZGA genes. These results suggest that multiple Dux paralogs are expressed to ensure a sufficient amount of functional Dux and its paralogs which are generated during a short period of minor ZGA with a low transcriptional activity. The mechanism by which multiple Dux paralogs are expressed is discussed.

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Zoology

Introduction

In mouse oocytes, genes are actively transcribed during the growth phase, and then silenced at the end of their growth1. This transcriptionally inactive state remains after fertilization. Zygotic genome activation (ZGA) is initiated at the mid to late S-phase of the 1-cell stage2. ZGA proceeds in two phases, minor and major ZGA, and the pattern of gene expression is dramatically changed between these two phases. During minor ZGA, which occurs from the S phase of the 1-cell stage to the G1 phase of the 2-cell stage, a relatively low level of transcription occurs in a large part of gene and intergenic regions, and regions that code for retrotransposons. However, during a subsequent activation that occurs up to the G2 phase of the 2-cell stage, i.e., major ZGA, the number of transcribed genes and transcription from intergenic regions decrease, whereas the expressions of particular genes are greatly increased3,4. Abe et al. (2018)5 showed that minor ZGA is a prerequisite for the occurrence of major ZGA. In that study, after the temporal inhibition of minor ZGA by 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-benzimidazole (DRB), a reversible inhibitor of RNA polymerase II, transcription was initiated in the pattern of minor ZGA at the time when major ZGA normally occurred. However, it remains to be elucidated how minor ZGA regulates major ZGA.

Recently, it was suggested that Dux is transcribed during minor ZGA and regulates the expression of some genes during major ZGA6–8. When Dux expression is induced in myoblasts and mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC), hundreds of major ZGA genes are upregulated7,8. Dux knockout reduces the expression of some of major ZGA genes in 2-cell stage embryos6. In addition, microinjection of cRNA encoding Dux into blastomeres of late 2-cell stage embryos results in the arrest of embryos at the 4-cell stage9, suggesting that transient expression of Dux is necessary during minor ZGA to induce the transcription of some of major ZGA genes. In Dux-knockout mice, viable offspring can be obtained but the litter size is small6,10,11.

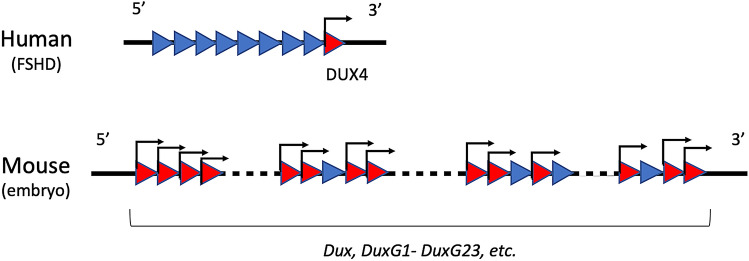

In humans, DUX4, which is considered an ortholog of mouse Dux, is a gene that is found within tandem repeats consisting of DUX4 paralogs that differ by only a few bases from each other12. DUX4 is localized at the telomere end of the repeats. These tandem repeats are located at pericentromeric regions that are usually heterochromatinized, which prevents their expression in most types of cells. DUX4 is the causative gene for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), the third most common muscular dystrophy13–17. In this disease, only DUX4 is aberrantly expressed from the tandem repeats18,19. In mice, Dux is also known to be a gene within tandem repeats and some of its paralogs have been identified20: in this study, Dux and Dux paralogs are collectively called Dux family. However, it is not known where Dux is located in the tandem repeats.

To date, several Dux family genes have been identified, but they are not expressed in early embryos. To identify the function of the Dux family and the mechanism regulating their expressions in preimplantation embryos, we first need to identify the Dux family gene(s) that is (are) expressed. Here, we report that some Dux family genes are expressed and function in early mouse pre-implantation embryos.

Results

Diversity of Dux paralogs in mouse genome and their expression in early preimplantation embryos

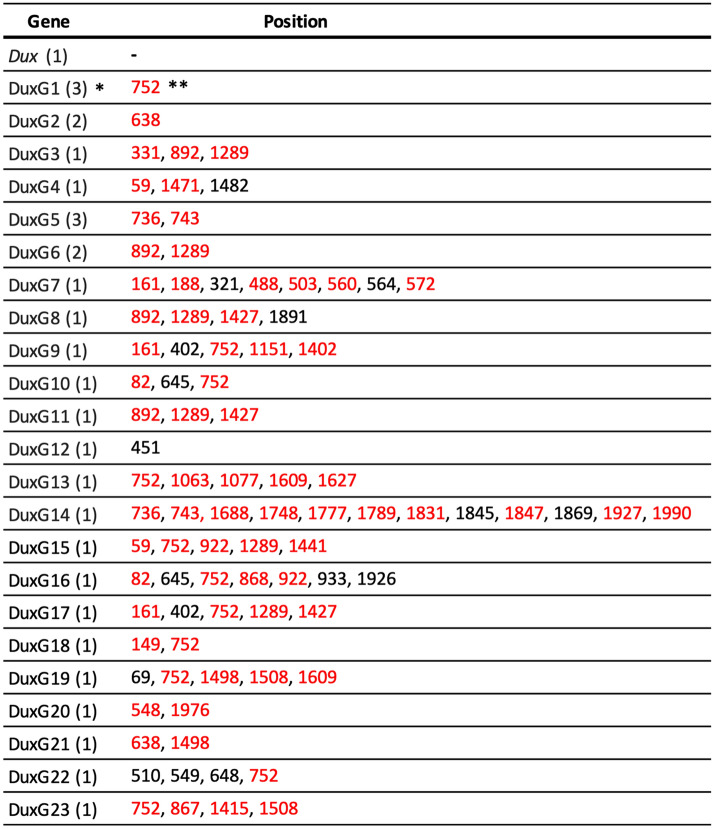

To identify the paralogs of Dux, their coding regions were amplified by PCR using primers with sequences at the ends of Dux, and mouse genome as the template. The amplified cDNAs were cloned and were sequenced. Although out of 30 clones, some of them were overlapped, 23 different Dux paralogs were identified, which were designated DuxG1 to DuxG23, in addition to the canonical Dux (Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. S1). These paralogs were only 1–12 bases different from Dux, and in all of them, no termination codon was recognized in the sequence, indicating that there are a large number of Dux family genes (more than 24 genes).

Table 1.

Dux family genes identified in the mouse genome.

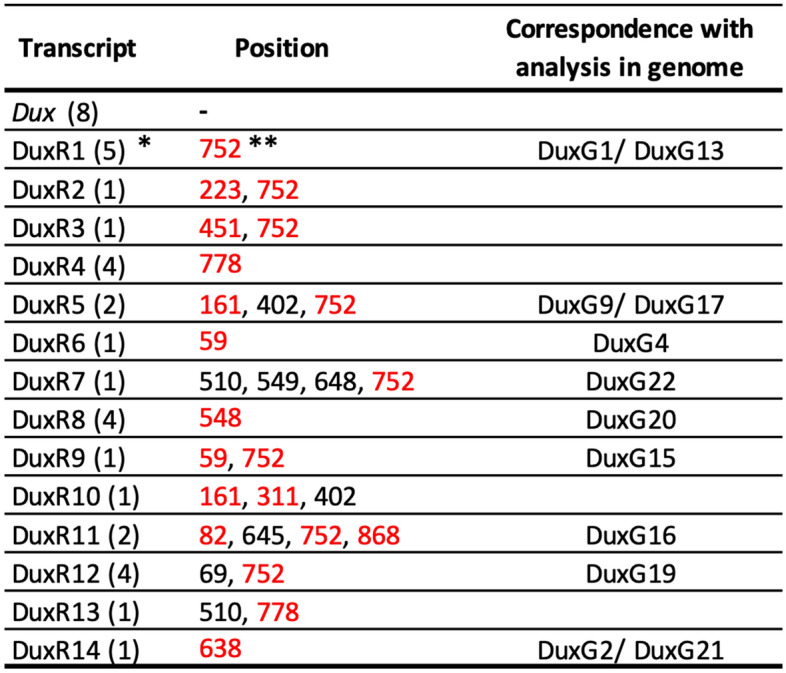

*Parentheses indicate the number of clones obtained.

**Red letters indicate the position of non-synonymous replacements.

We examined whether these genes were expressed in early preimplantation embryos. To this end, PCR was performed using cDNA that had been reverse-transcribed using transcripts from early 2-cell stage embryos as the template. The primers used were capable of amplifying the whole coding regions (CDS) of Dux and all of the aforementioned Dux paralogs. However, no amplicon was obtained. Therefore, we decided to amplify the upstream region (31–889 bps) of the Dux family, which contains many mutations. After the PCR using the primers that matched all of them, the amplified cDNA was cloned and the resulting 37 clones were sequenced. As a result, 15 different Dux family sequences including Dux were identified. These sequences, excluding Dux, were designated DuxR1 to DuxR14 (Table 2 and Supplemental Fig. S2). In 37 clones, 8 clones were identical to Dux, and yet only comprised less than 1/4 of the 37 clones. Nine of the 14 sequences matched the aforementioned Dux paralog genes, suggesting that these Dux paralog genes did not come from the sequencing artifacts of the canonical Dux. In addition, none of these sequences had a stop codon in the middle of the sequence, which would lead to translation termination (Supplemental Fig. S3). When the nucleotide sequences of DuxR1 to R14 were converted into amino acid sequences, there were only a few amino acid differences from DUX (Table 2). These results suggest that many Dux family genes in tandem repeats are expressed in early 2-cell stage embryos and encode functional proteins.

Table 2.

Dux family transcripts expressed in the early 2-cell stage embryos.

*Parentheses indicate the number of clones obtained.

**Red letters indicate non-synonymous replacements.

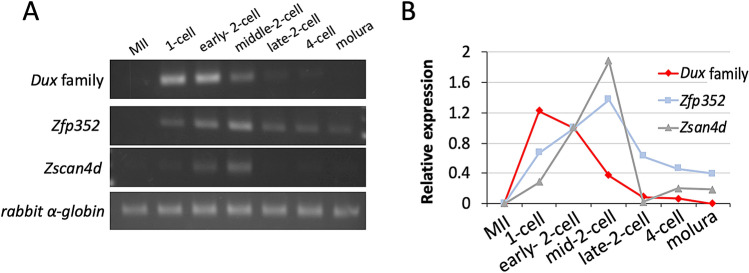

Expression of Dux family genes during preimplantation development

Changes in the expression levels of Dux family genes during preimplantation development were examined by RT-PCR, using the aforementioned primers that matched all of the Dux family genes expressed in the 2-cell stage embryos. Although the expression of Dux family genes was not detected in unfertilized eggs, it was detected in 1-cell stage embryos after fertilization. It was decreased during the 2-cell stage and hardly detected at the late 2-cell stage (Fig. 1A,B and Supplemental Fig. S4A). This indicates that the Dux family is a group of genes that are transiently expressed during the minor ZGA stage. We also examined the expression of two genes, Zfp352 and Zscan4d, which are targets of Dux8. Their expression followed that of the Dux family genes. They were detected in 1-cell stage embryos, increased until the mid-2-cell stage, and then started decreasing (Fig. 1A,B and Supplemental Fig. S4A).

Figure 1.

Expression of the Dux family, Zfp352, and Zscan4d during preimplantation development. Fifty MII stage oocytes and embryos at the 1-, 2-(early, mid and late), 4-cell, and morula stages were collected at 13, 16, 24, 32, 40 and 70 h post insemination (hpi), respectively, and subjected to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Two independent experiments were conducted and similar results were obtained. (A) Electrophoresis images of the Dux family, Zfp352, Zscan4d, and rabbit α-globin (external control) PCR products. (B) The band densities in (A) were quantified using ImageJ. The band densities of the three genes are relative to that of rabbit α-globin. The values at the early 2-cell stage were set to 1 and the relative values were calculated. The average value from two experiments is shown.

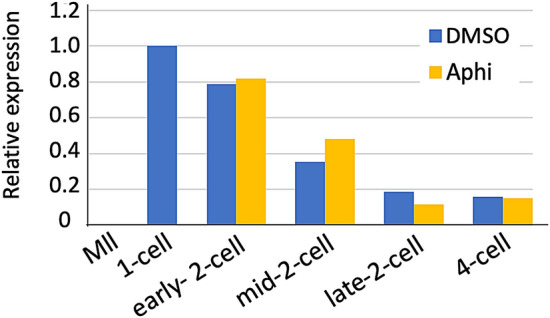

Involvement of DNA replication in the expression of the Dux family at the 2-cell stage

The expression levels of some minor ZGA genes decrease during the 2-cell stage and depend on DNA replication21,22. Therefore, DNA replication was inhibited using aphidicolin, an inhibitor of DNA polymerase, and the expression of the Dux family was examined at the late 2- to 4-cell stage to investigate whether the expression of the Dux family is suppressed by DNA replication. The results showed no significant differences compared to the control (Fig. 2). Therefore, the decrease in the expression of the Dux family during the 2-cell stage does not depend on DNA replication.

Figure 2.

Effect of inhibition of DNA replication on the suppression of Dux family expression during the 2-cell stage. Fifty MII stage oocytes and embryos at the 1-, 2-(early, mid and late), 4-cell, and morula stages were collected at 13, 16, 24, 32 and 40 hpi, respectively. The expression levels of Dux family genes were examined by RT-PCR. Rabbit α-globin was used as an external control. The expressions of Dux family genes are relative to that of rabbit α-globin. Gene expression from the 1-cell stage was set to 1 and the relative values were calculated. Two independent experiments were conducted and similar results were obtained. The average value from two experiments is shown.

Function of the Dux family

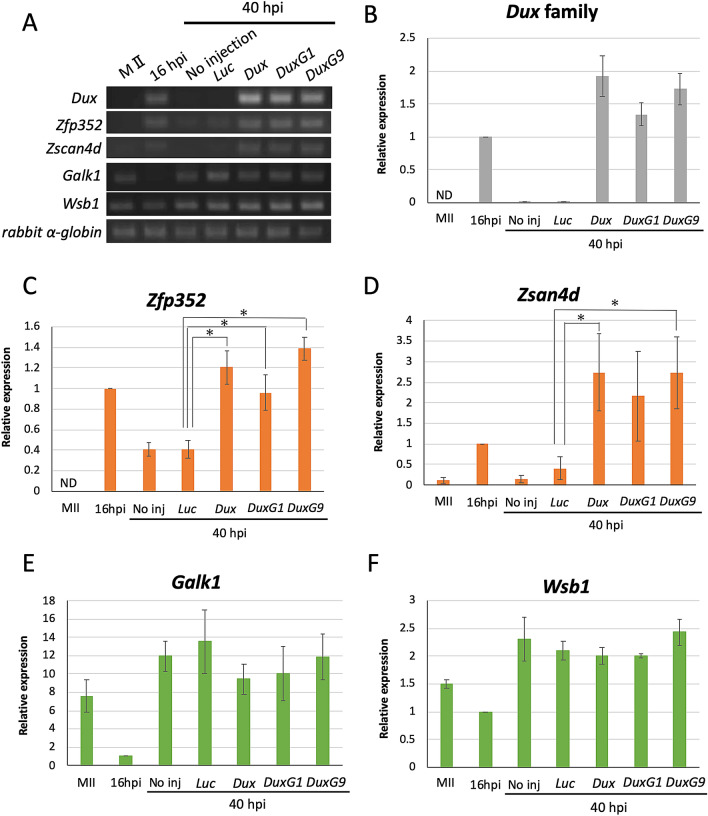

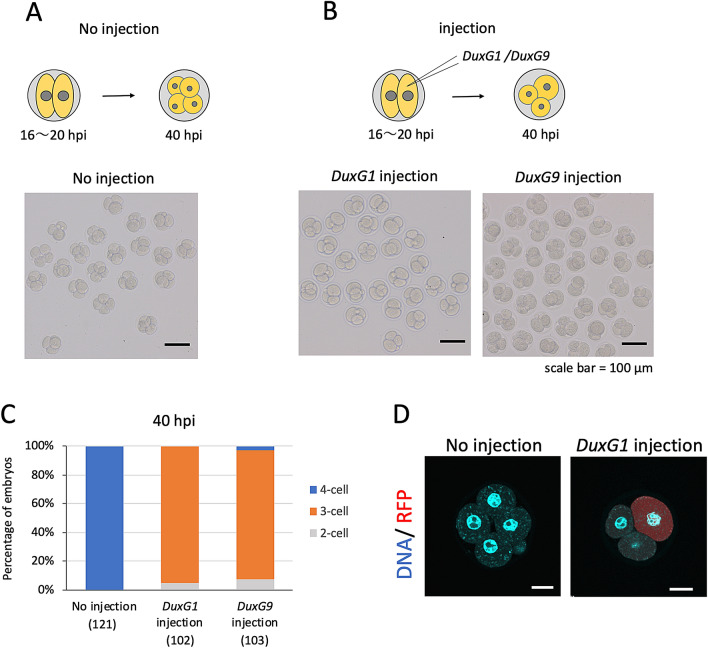

We overexpressed some of the Dux family genes to investigate their function in early pre-implantation embryos. We chose DuxG1 and DuxG9 because their expression was detected in 2-cell stage embryos, in addition to Dux (Table 2). DuxG1 has frequently been detected in experiments to identify the Dux family genes and DuxG9 has the most mutations compared to Dux among the Dux family genes whose expressions had been observed (Table 2). The cRNA encoding DuxG1, DuxG9, or Dux was microinjected into one blastomere of 2-cell stage embryos between 16 and 20 h post insemination (hpi), because the expression of the Dux family was found to peak at 13 hpi and decrease at 16 hpi. Thereafter, the embryos were collected at 40 hpi and examined for the expression of the Dux family and the Dux target genes Zfp352 and Zscan4d. The expressions of both of the Dux target genes were increased by the overexpression of Dux family genes (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. S4B). It should be noted that the levels of the Dux target genes in the embryos overexpressing DuxG1 or DuxG9 were almost the same as those overexpressing Dux, suggesting that DUXG1 and DUXG9 have almost the same level of the activity as Dux to increase the expression of Dux target genes. The expressions of the Dux-independent genes Wsb1 and Galk18 showed no change after overexpression of DuxG1, DuxG9, or Dux (Fig. 3E,F). The embryos that were microinjected with DuxG1 or DuxG9 in a single blastomere developed to the 3-cell stage at 40 hpi, which is the time most of the control embryos developed to the 4-cell stage (Fig. 4). To confirm that the microinjected blastomere did not divide, red fluorescent protein (RFP) cRNA was microinjected together with DuxG1 cRNA. The results showed that the microinjected blastomeres did not divide (Fig. 4D).

Figure 3.

Effects of Dux family overexpression on the change in gene expression pattern in the early 2- and 4-cell stages. cRNA encoding Dux, DuxG1, DuxG9, or firefly luciferase (Luc, control) were microinjected into a blastomere of a 2-cell stage embryo at 16–20 hpi and cultured in vitro. Cells were collected and RT-PCR was conducted to amplify Dux family, Zfp352, Zscan4d, Galk1, Wsb1 and rabbit α-globin (external control) at 40 hpi. MII stage oocytes and non injected embryos at 16 and 40 hpi were also collected for RT-PCR. Thirty cells were used for each sample. (A) Electrophoresis images of PCR products. (B–F) The band densities in (A) were quantified using image J. The band density of each gene is relative to that of rabbit α-globin. The values at the early 2-cell stage (16 hpi) were set to 1 and the relative values were calculated. Five (Dux family, Zfp352 and Zscan4d) and three (Galk1 and Wsb1) independent experiments were conducted. Error bars represent SE. Asterisks indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) by paired Student t-test.

Figure 4.

Effect of overexpression of the Dux family on the development of 2-cell stage embryos. A blastomere of a 2-cell stage embryo was microinjected with cRNA encoding DuxG1 or Dux G9 and then cultured until 40 hpi in vitro. Control embryos were not injected. (A,B) Schematic diagrams of the experiments. Photograph of embryos that were injected with (A) or without (B) DuxG1 or DuxG9 cRNA. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) The developmental stages of the embryos at 40 hpi. Parentheses indicate the number of embryos observed at 40 hpi. (D) DuxG1 and RFP cRNA were simultaneously microinjected into a blastomere of 2-cell stage embryos and cultured until 45 hpi in vitro. Then the embryos were immunostained with RFP antibody at 45 hpi. DNA was detected by DAPI staining. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Discussion

We identified 23 Dux family genes whose sequences were very similar to that of Dux in genomic DNA (DuxG1-G23; Table 1, Supplemental Fig. S1), and 14 mRNAs that were transcribed in 2-cell stage embryos (DuxR1-R14; Table 2, Supplemental Fig. S2). When the sequences of DuxR1 to R14 were compared to those of DuxG1 to G23 of the genome, there were nine matched pairs (Table 2). Therefore, five transcripts were derived from genes that had not yet been identified. Furthermore, because the sequences of the transcripts in nine of the aforementioned pairs were not full-length, the possibility cannot be excluded that they might have been derived from genes different from those described above. It is thus likely that there are many Dux family genes that have not yet been identified. Although it is unknown where these genes are located on the genome, in a DNA-FISH experiment using Dux as a probe, only one signal was found on chromosome 1020, suggesting that all (or most) of the Dux family genes are present in Dux tandem repeats.

Erroneous expression of DUX4 in human muscle causes FSHD18,19. In this disease, the number of tandem repeats is decreased from 11–100, which is normal, to less than 10, which leads to a change in chromatin structure, resulting in only the expression of DUX4 that is located at the telomere end of the tandem repeats23. However, as described above, because there are at least 29 Dux family genes in mice, it is unlikely that expression occurs due to a small number of repetitions in early preimplantation embryos of mice. Furthermore, in FSHD, only one DUX4 gene is expressed, whereas in mouse preimplantation embryos, at least 15 Dux family genes including Dux are expressed (Table 2; Fig. 5). Therefore, the mechanism by which Dux family genes is expressed from the 1-cell stage to the early 2-cell stage is likely to differ from that of muscle cells. The mechanism seems to be related to the chromatin structure specific to the embryos at these stages. The tandem repeats containing DUX4 are present in the subtelomeric region in primates and African orders (such as those to which elephants and hyrax belong), and tandem repeats of DUXC, a homologue of DUX4, are present around the centromere in bovine and Laurasian orders (such as those to which dogs and dolphins belong)24. The areas around the subtelomere and centromere regions form heterochromatin and expression from these areas is suppressed. Although tandem repeats from mice containing the Dux family are located near the center of chromosome 10 and not near telomeres or centromeres20, a structure similar to that of subtelomeres has been observed there20,24,25. Therefore, it is likely that tandem repeats also form heterochromatin and are silenced in adult mouse cells. On the other hand, the chromatin structure is extremely loosened in 1-cell stage embryos and become tightened during the 2-cell stage26. Although in adult cells, pericentromeric regions form constitutive heterochromatin, which gathers to form chromocenters, they are not formed at the 1-cell and early 2-cell stages. This loosened chromatin structure causes promiscuous transcription from many regions all over the genome including pericentromeric regions27–29. Therefore, the tandem repeat containing the Dux family may have a loosened chromatin structure without forming heterochromatin at the 1-cell and early 2-cell stages, leading to the expression of the Dux family genes. In this case, unlike the expression of DUX4 alone in human FSHD, the Dux family in the tandem repeats would be widely expressed in preimplantation embryos. Indeed, we found that several Dux family genes were expressed in 2-cell stage embryos (Table 2).

Figure 5.

DUX4 expression in human FSHD myocytes and Dux family expression in mouse embryos. In human FSHD, only DUX4, which is located at the end of tandem repeats, is expressed in muscle, whereas in early mouse embryos, a large number of Dux paralogs are expressed during minor ZGA. The red and blue triangles represent active and inactive Dux family genes, respectively.

We have shown that the Dux family is a group of genes that are transiently expressed during minor ZGA (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. S4A). DNA replication at the 2-cell stage is involved in the reduced expression of genes that are transiently expressed only at the time of minor ZGA30. When DNA replication is inhibited at the 2-cell stage, the expression of some of these genes is maintained even at the late 2-cell stage3,21. Therefore, we considered that the suppression of the Dux family genes at the late 2-cell stage might be regulated by DNA replication. However, inhibition of DNA replication by aphidicolin did not affect the expression of the Dux family (Fig. 2). Alternatively, the reduction of their expression at the 2-cell stage is related to the expression of the retrotransposon LINE131. Therefore, it is possible that the expression of Dux is suppressed by LINE1 in the 2-cell stage, and heterochromatin is gradually formed during subsequent embryonic development, which becomes responsible for the suppression of the Dux family genes.

The C-terminus of mouse Dux and human DUX4 is conserved20,32. The result of an experiment to determine the domain in human DUX4 involved in the occurrence of FSHD revealed that the C terminus domain was important33. Furthermore, the overexpression of DUX4 caused the expression of Zscan4, a ZGA gene, in HeLa cells, but DUX4 lacking the C-terminus did not. We examined the sequences of C-terminal region (1981–2025 bps) in 23 Dux family genes obtained in this study, and found only one mutation in this region in a single gene, DuxG14. This suggests that most Dux family genes might be functional.

To investigate the function of the Dux family in preimplantation embryos, we overexpressed those genes. Their expressions increased the expression of some major ZGA genes in pre-implantation embryos (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. S4B). In this experiment, we overexpressed DuxG1, DuxG9, and Dux, because their expressions were confirmed in 2-cell stage embryos. Because microinjection of the same amount of these three types increased the expression of Dux target genes to similar levels, this suggests that the Dux family genes may have similar functions in early preimplantation embryos.

In the present study, we found that there are a number of Dux family genes that are expressed during minor ZGA. These genes seem to function similarly to regulate the expression of some major ZGA genes. These characteristics seem to be suitable to ensure a sufficient amount of functional Dux and its paralogs. Because transcription is regulated independently of enhancers during minor ZGA, there seems to be no mechanism to enhance the expression of particular genes during this period3,30,34. In addition, transcriptional activity is low and the period (less than 10 h) is not long during minor ZGA2. Therefore, although a large number of genes are expressed during ZGA, the expression level of each gene is very low3,4. Under these conditions, an efficient way to produce a sufficient amount of transcripts would be to have multiple genes with similar function, as was found in the Dux family.

Materials and methods

Collection and culture of oocytes and embryos

MII stage oocytes were obtained from 3-week-old C57BL/6N (B6N) (Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) or B6D2F1 (BDF1) (Japan SLC, Inc.) female mice, which were intraperitoneally administered with 5 IU of serotropin (ASKA Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) followed by 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (ASKA Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) for 48 h later to induce superovulation. The mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and MII stage oocytes were obtained from the ampulla of oviduct in human tubal fluid (HTF) medium35. Spermatozoa were obtained from the cauda epididymis of adult B6N or ICR male mice (Japan SLC, Inc.), and cultured in HTF medium. In vitro fertilization was performed by adding sperm to HTF medium containing MII stage oocytes. Six hours after insemination, the fertilized oocytes were transferred to K+-modified simplex optimized medium (KSOM)36 to remove sperm and cumulus cells. Only fertilized oocytes containing two pronuclei were culled under a stereomicroscope, and then cultured in KSOM. The medium was covered with mineral oil and placed in an incubator at 38 °C containing 5% CO2. Embryos at various developmental stages were collected according to the following time schedule: 1-cell stage, 10 h post insemination (hpi); early 2-cell stage, 16 hpi; mid-2-cell stage, 24 hpi; late-2-cell stage, 32 hpi; 4-cell stage, 40 hpi; morula stage, 70 hpi.

All of the procedures using animals were reviewed and approved by the University of Tokyo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Inhibition of DNA replication

To inhibit DNA replication at the 2-cell stage, embryos were transferred to KSOM medium containing 3 µg/mL aphidicolin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), a DNA replication inhibitor, at 14 hpi at which time most of the embryos had just cleaved. As a control, embryos were cultured in KSOM medium containing 0.3% DMSO, which is the solvent that was used to resuspend aphidicolin.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Fifty (unless otherwise specified) oocytes or embryos were collected in 200 µL ISOGEN (Nippon Gene Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). After adding rabbit α-globin as an external control, RNA extraction was performed. Genomic DNA was removed using RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), and RNA was extracted after adding 200 µL ISOGEN. Reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers from a PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc, Shiga, Japan). PCR was performed using Ex taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Inc). The primers and conditions used for PCR are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

Vector construction

To identify Dux paralogs in the mouse genome, constructs containing the coding regions (CRs; 2025 bps) of Dux paralogs were prepared. The CDSs of full-length Dux paralogs were amplified by PCR using the genome of C57BL6N mouse as a template, DNA polymerase with proofreading activity (KOD-Plus-; TOYOBO Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), and the following primers.

Forward: 5′-ATGAATTCGCCACCATGGCAGAAGCTGGCAGC-3′.

Reverse: 5′-ATGAATTCTCAGAGCATATCTAGAAGAGTCTGATATTCTT-3′.

These primers contained a Kozak sequence and a restriction enzyme site (EcoR1) to allow for the constructs to also be used for overexpression experiments. After amplification, an additional PCR was performed using Ex taq (Takara Bio Inc) to add a protruding end of adenosine at 95 °C for 2 min and at 72 °C for 15 min. The amplified DNA was electrophoresed on an agarose gel, and the PCR fragment was purified according to the procedure in the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega Corporation). The purified PCR fragment was cloned using a TOPO TA cloning kit (pCRII TOPO vector; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and introduced into DH5α (TaKaRa, Cell density: 1–2 × 109 bacteria/mL). Thereafter, the plasmid was extracted using a Plasmid DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Chiyoda Science Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The extracted plasmid was subjected to DNA sequencing using a 3500 Genetics Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Because the full length Dux CDS is too long to be completely sequenced using a single set of primers (2025 bps), four sets of forward and reverse primers were used (Supplemental Table S2).

To identify the transcripts expressed in 2-cell stage embryos, cDNA was prepared as described above in the RT-PCR section, and part of the Dux CDS (31–889 bps) was amplified using the following primers: forward, 5′-AGTGGTGTGGCACGGGAA-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCTCTCCTGGGAACCTTCA-3′. The PCR products were inserted into a pCRII TOPO vector and used for sequencing as described above.

To overexpress Dux, artificial gene synthesis of Dux was outsourced to Thermo Fisher Scientific, because the Dux sequence could not be obtained by cloning using the genome as a template. Using the plasmid containing Dux as a template, full-length Dux CDS was amplified by PCR and the products were inserted into a pCRII TOPO vector and used for sequencing.

In vitro transcription

In vitro transcription (IVT) was performed to prepare cRNAs encoding Dux, DuxG1, DuxG9, and firefly luciferase (Luc), which had been prepared previously. The expression vectors containing Dux, DuxG9, and Luc were treated with the restriction enzyme EcoRV (FastDigest, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The expression vector containing DuxG1 was treated with SpeI (FastDigest, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). They were purified by phenol chloroform/ethanol precipitation. Thereafter, IVT was performed using a T7 or Sp6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After adding a poly (A) tail to the transcribed cRNA using a Poly (A) tailing kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), the cRNA was purified using a lithium chloride precipitation solution and dissolved in nuclease-free water.

Microinjection

cRNAs encoding Dux and Dux paralogs were adjusted to a concentration of 500 ng/µL, and ~ 10 pL cRNA and were microinjected into a blastomere of 2-cell stage embryos between 16 and 20 hpi in KSOM-HEPES medium covered with mineral oil. To discriminate the blastomere that had been microinjected, 500 ng/µL cRNA encoding red fluorescent protein (RFP) was microinjected together with the Dux paralog-encoding cRNA.

Immunocytochemistry

The embryos were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at room temperature for 20 min, and then washed with PBS containing 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich) (0.1% BSA in PBS) three times. The membrane was permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS (0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) at room temperature for 15 min. After being washed three times with 0.1% BSA in PBS, the embryos were treated with the primary antibody against RFP (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; diluted 500-fold with 0.1% BSA in PBS) overnight at 4 °C followed by treatment with the secondary antibody (AlexaFluor 568 donkey-anti rabbit IgG; Life Technologies; diluted 200-fold with 0.1% BSA in PBS) at room temperature for 1 h. After being washed with 0.1% BSA in PBS three times, the samples were mounted in VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) containing 3 µg/mL 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI: Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) on a glass slide. The fluorescence was observed using an FV3000 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported, in part, by Grants-in-Aid (to FA) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (#17K19318, #18H03970 and #19H05752).

Author contributions

F.A. conceived and supervised the study; K.S. and F.A. designed the experiments; K.S. performed the experiments; K.S., S.F., M.K., M.G.S., T.N., and F.A. analyzed the data; and K.S. and F.A. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-76538-9.

References

- 1.Moore GP, Lintern-Moore S, Peters H, Faber M. RNA synthesis in the mouse oocyte. J. Cell Biol. 1974;60:416–422. doi: 10.1083/jcb.60.2.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki F, Worrad DM, Schultz RM. Regulation of transcriptional activity during the first and second cell cycles in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 1997;181:296–307. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe K, et al. The first murine zygotic transcription is promiscuous and uncoupled from splicing and 3′ processing. EMBO J. 2015;34:1523–1537. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto R, Aoki F. A unique mechanism regulating gene expression in 1-cell embryos. J. Reprod. Dev. 2017;63:9–11. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2016-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe KI, et al. Minor zygotic gene activation is essential for mouse preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018;115:E6780–E6788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804309115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Iaco A, et al. DUX-family transcription factors regulate zygotic genome activation in placental mammals. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:941–945. doi: 10.1038/ng.3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendrickson PG, et al. Conserved roles of mouse DUX and human DUX4 in activating cleavage-stage genes and MERVL/HERVL retrotransposons. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:925–934. doi: 10.1038/ng.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiddon JL, Langford AT, Wong CJ, Zhong JW, Tapscott SJ. Conservation and innovation in the DUX4-family gene network. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:935–940. doi: 10.1038/ng.3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo M, et al. Precise temporal regulation of Dux is important for embryo development. Cell Res. 2019;29:956–959. doi: 10.1038/s41422-019-0238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Zhang Y. Loss of DUX causes minor defects in zygotic genome activation and is compatible with mouse development. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:947–951. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Iaco A, Verp S, Offner S, Grun D, Trono D. DUX is a non-essential synchronizer of zygotic genome activation. Development. 2020 doi: 10.1242/dev.177725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsuhashi S, et al. Nanopore-based single molecule sequencing of the D4Z4 array responsible for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14789. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13712-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt JE, et al. Analysis of the tandem repeat locus D4Z4 associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:1287–1295. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.8.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winokur ST, et al. The DNA rearrangement associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy involves a heterochromatin-associated repetitive element: implications for a role of chromatin structure in the pathogenesis of the disease. Chromosome Res. Int. J. Mol. Supramol. Evol. Asp. Chromosome Biol. 1994;2:225–234. doi: 10.1007/bf01553323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabriels J, et al. Nucleotide sequence of the partially deleted D4Z4 locus in a patient with FSHD identifies a putative gene within each 3.3 kb element. Gene. 1999;236:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixit M, et al. DUX4, a candidate gene of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, encodes a transcriptional activator of PITX1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:18157–18162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snider L, et al. RNA transcripts, miRNA-sized fragments and proteins produced from D4Z4 units: new candidates for the pathophysiology of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:2414–2430. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geng LN, et al. DUX4 activates germline genes, retroelements, and immune mediators: implications for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Dev. Cell. 2012;22:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewitt JE. Loss of epigenetic silencing of the DUX4 transcription factor gene in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:R17–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clapp J, et al. Evolutionary conservation of a coding function for D4Z4, the tandem DNA repeat mutated in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:264–279. doi: 10.1086/519311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis W, Jr, De Sousa PA, Schultz RM. Transient expression of translation initiation factor eIF-4C during the 2-cell stage of the preimplantation mouse embryo: identification by mRNA differential display and the role of DNA replication in zygotic gene activation. Dev. Biol. 1996;174:190–201. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonehara H, Nagata M, Aoki F. Roles of the first and second round of DNA replication in the regulation of zygotic gene activation in mice. J. Reprod. Dev. 2008;54:381–384. doi: 10.1262/jrd.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemmers RJ, et al. A unifying genetic model for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Science. 2010;329:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1189044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leidenroth A, et al. Evolution of DUX gene macrosatellites in placental mammals. Chromosoma. 2012;121:489–497. doi: 10.1007/s00412-012-0380-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flint J, et al. Sequence comparison of human and yeast telomeres identifies structurally distinct subtelomeric domains. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:1305–1313. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.8.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ooga M, Fulka H, Hashimoto S, Suzuki MG, Aoki F. Analysis of chromatin structure in mouse preimplantation embryos by fluorescent recovery after photobleaching. Epigenetics. 2016;11:85–94. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1136774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed K, et al. Global chromatin architecture reflects pluripotency and lineage commitment in the early mouse embryo. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama T, Suzuki O, Matsuda J, Aoki F. Dynamic replacement of histone H3 variants reprograms epigenetic marks in early mouse embryos. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Probst AV, et al. A strand-specific burst in transcription of pericentric satellites is required for chromocenter formation and early mouse development. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultz RM. Regulation of zygotic gene activation in the mouse. BioEssays News Rev. Mol. Cell. Dev. Biol. 1993;15:531–538. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Percharde M, et al. A LINE1-nucleolin partnership regulates early development and ESC identity. Cell. 2018;174:391–405 e319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eidahl JO, et al. Mouse Dux is myotoxic and shares partial functional homology with its human paralog DUX4. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:4577–4589. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitsuhashi H, et al. Functional domains of the FSHD-associated DUX4 protein. Biol. Open. 2018 doi: 10.1242/bio.033977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nothias JY, Majumder S, Kaneko KJ, DePamphilis ML. Regulation of gene expression at the beginning of mammalian development. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:22077–22080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quinn P, Begley AJ. Effect of human seminal plasma and mouse accessory gland extracts on mouse fertilization in vitro. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1984;37:147–152. doi: 10.1071/bi9840147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawitts JA, Biggers JD. Culture of preimplantation embryos. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:153–164. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25012-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.