Abstract

Background:

Internalizing disorders (IDs), consisting of syndromes of anxiety and depression, are common, debilitating conditions often beginning early in life. Various trait-like psychological constructs are associated with IDs. Our prior analysis identified a tripartite model of Fear/Anxiety, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect among symptoms of anxiety and depression and the following constructs in youth: anxiety sensitivity, fearfulness, behavioral activation and inhibition, irritability, neuroticism, and extraversion. The current study sought to elucidate their overarching latent genetic and environmental risk structure.

Methods:

The sample consisted of 768 juvenile twin subjects ages 9–14 assessed for the nine, abovementioned measures. We compared two multivariate twin models of this broad array of phenotypes.

Results:

A hypothesis-driven, common pathway twin model reflecting the tripartite structure of the measures were fit to these data. However, an alternative independent pathway model provided both a better fit and more nuanced insights into their underlying genetic and environmental risk factors.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest a complex latent genetic and environmental structure to ID phenotypes in youth. This structure, which incorporates both clinical symptoms and various psychological traits, informs future phenotypic approaches for identifying specific genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ID risk.

Keywords: anxiety, child, depression, fear, genetics, twin study

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Anxiety and depressive disorders (i.e., internalizing disorders [IDs]) typically start in late childhood or adolescence (Merikangas et al., 2010; Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998) and demonstrate substantial prevalence and chronicity in adulthood (Kessler et al., 2005). Prior studies have applied factor analytic approaches to IDs in community samples of adults (Krueger, 1999) and juveniles (Lahey et al., 2008) with similar findings: evidence for a single, higher-order “internalizing” factor that accounts for correlations among anxiety and depressive disorders and differentiates itself from an “externalizing” factor. The internalizing factor typically encompasses two highly correlated, first-order descriptive factors, the first roughly corresponding to a “fear” dimension indicated by panic and phobic disorders, and the second an “anxious misery” dimension onto which major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder load. Genetic epidemiological studies support a similar structure of genetic and environmental risk factors among psychopathology in adults (Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Wolf et al., 2010). Extant twin studies in developing children suggest a complex unfolding of internalizing risk factors with corresponding age-related changes in the sources of genetic influence (Boomsma, van Beijsterveldt, & Hudziak, 2005; Lamb et al., 2010; Waszczuk, Zavos, Gregory, & Eley, 2016).

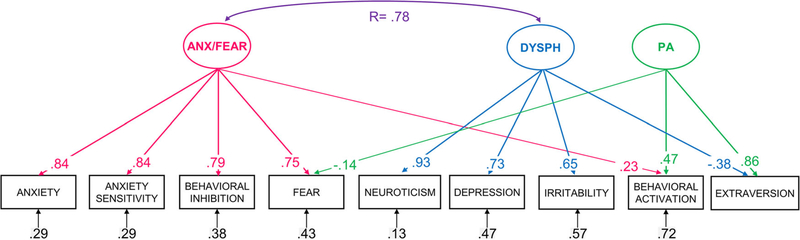

An extensive research literature suggests that various dimensional, trait-like constructs index shared or specific components of ID risk. Our prior study (Lee et al., 2017) simultaneously investigated the complex interrelationships among symptoms of anxiety and depression and seven key psychological constructs: anxiety sensitivity, fearfulness, behavioral activation and inhibition, irritability, neuroticism, and extraversion. We confirmed a primary tripartite structure in children ages 9–14 comprising Anxiety/Fear, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect dimensions (Figure 1) reminiscent of ones reported in adult and youth studies of psychopathology (reviewed in Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998 and Anderson & Hope, 2008). Those studies typically identify three dimensions: (a) negative affect shared between nonspecific anxiety and depressive symptoms, (b) low positive affect specific to depression and, more variably, social phobia, and (c) physiological hyperarousal specific to panic. These vary somewhat with the measures included (i.e., fear vs. anxiety, which anxiety disorders, which survey instruments). The main difference, however, was that the structure that we found simultaneously fit both clinical symptoms and trait constructs. Such findings support refined transdiagnostic frameworks proposed under the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; Insel et al., 2010) as well as alternative classification systems like the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (Kotov et al., 2017).

FIGURE 1.

Tripartite phenotypic (descriptive) model from Lee at al. (2017). It contains three latent dimensions: ANX/FEAR, DYSPH, and PA. DYSPH, dysphoria; PA, positive affect

Viewed as potential intermediate or “endo” phenotypes (Gottesman & Gould, 2003), such trait-like psychological constructs are as complex as IDs themselves (Flint, Timpson, & Munafo, 2014). Nonetheless, endophenotypes offer potential developmental insights into psychopathology when their latent structure is examined (Kendler & Neale, 2010) and have recently shown promise for dissecting molecular genetic components of mental illness (Greenwood et al., 2019). Early studies support subsets of measures that index shared or specific components of genetic risk for IDs (reviewed in Savage, Sawyers, Roberson-Nay, & Hettema, 2016). However, no prior research has used a genetically informative sample of youth to investigate the multifactorial relationships among such a wide array of overarching constructs hypothesized to drive the tendency for individuals to experience negative emotional symptoms and develop IDs. Thus, clarifying relationships among these constructs in youth is important for understanding the developmental unfolding of psychopathology. The current study examines the genetic and environmental interrelationships among the nine symptom-based and trait-like phenotypes included in our prior investigation (Lee et al., 2017). The primary analyses compare alternative models to test the hypothesis that underlying etiological factors conform to the tripartite structural model found in that prior study.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Participants and measures

Caucasian twins aged 9–14 years (mean, 11.3 years) were recruited for the Virginia Commonwealth University Juvenile Anxiety Study (VCU-JAS) from the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry (Lilley & Silberg, 2013). VCU-JAS used a community sampling design unselected for any particular outcome phenotypes. Fifty-three percent were female, and one-third of the pairs were monozygotic (Table S1). Caucasian twins were recruited to minimize phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity for the overall project. VCU-JAS assessed a broad array of putative psychological and biological indicators of internalizing psychopathology (Carney et al., 2016). These included survey instruments assessing dimensional aspects of children’s symptomatology or temperament and psychological and physiological measures collected during laboratory paradigms. Only the child self-report survey measures assessing the above-described constructs are included in the current analyses. Of the 398 complete twin pairs who participated in VCU-JAS, data from these measures were available from 768 children. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at VCU and NIMH. After obtaining written informed consent from parents and assent from minor children, research protocols were conducted by trained research assistants in laboratory settings at VCU in Richmond, Virginia and at the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH-IRP), part of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

A battery of nine psychometrically sound self-report instruments was chosen to assess recent internalizing symptomatology and the relevant psychological traits. These are described in greater detail in (Carney et al., 2016) and Table S2 and summarized here: anxiety (Screen for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders [SCARED]—Child Version (Birmaher et al., 1997)), depression (Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire [SMFQ] (Angold et al., 1995)), anxiety sensitivity (Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index [CASI]), fear (Fear Survey Schedule for Children-Revised [FSSC-R] (Ollendick, 1983)), behavioral inhibition/activation (Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System [BIS/BAS] Scales (Carver & White, 1994)), irritability (Affective Reactivity Index (Stringaris, Goodman, et al., 2012)), neuroticism, and extraversion (Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, Junior version (Eysenck, 1965)). Sum scores were analyzed for all measures. Each has demonstrated acceptable inter-item (Cronbach’s α = .77–.96) and test-retest (r = .61–.83) reliability in the current sample.

2.2 |. Analyses

Primary analyses utilized structural equation modeling (SEM; Neale & Cardon, 1992) to fit selected twin models to the nine phenotypic measures. Since MZ twins share 100% of their segregating genes whereas DZ twins share 50% on average, SEM conducted in twins can decompose the variance of each measured phenotype into additive genetic (A), familial environmental (C), and unique environmental (E) etiologic influences. Using multivariate SEM, we specifically compared two types of etiologic structures of the measures based on previous findings at the phenotypic level (Lee et al., 2017)—common pathway versus independent pathway models. Also, given the well-known sex differences for anxiety and depressive syndromes, we ran a series of t tests to examine the effects of sex on each construct before including it as a covariate in the twin models.

2.2.1 |. Common pathway model to assess hierarchical factor structure

A common pathway model allows for individual measured phenotypes to load onto higher-order latent factors possessing their own variance components while specific components load into individual phenotypes to account for residual variance not accounted for by the higher-order constructs. Previous exploratory factor analyses revealed that the nine measures differentially loaded onto three latent dimensions representing Anxiety/Fear, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect. Thus, we assessed whether this same tripartite structure would fit well at the etiologic level using twin SEM of those Anxiety/Fear, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect factors. Note that only the pathways previously found (Figure 1) were allowed in this model. Correlations between A, C, and E factors for Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria were freely estimated due to their strong phenotypic correlation (r = .77). More parsimonious submodels were then tested and compared with fit statistics (a) likelihood ratio test (LRT) operationalized as twice the log-likelihood difference (−2LL; Wilks, 1938) and (b) Akaike information criteria (AIC; Akaike, 1987). These submodels assessed the necessity of particular sets of model parameters to best fit these data: A, C, and E correlations; common AL, CL, and EL influences for each latent dimension; and measure-specific AS and CS only, since specific ES effects cannot be dropped as they also contain error variance for each measure, respectively.

2.2.2 |. Independent pathway model to assess novel etiologic structural relationships

The common pathway model estimates A, C, and E influences on the higher-order latent dimensions of Anxiety/Fear, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect found in the previous phenotypic structure. In contrast, the independent pathway model explores more complex etiologic patterns that might not readily be revealed by studying unrelated individuals. Independent pathway models allow for all measured phenotypes to differentially load onto multiple common A, C, and E latent factors directly instead of restricting pathways through specific latent phenotypes. Specifically, we tested models allowing two, three, and four sets of common A, C, and E factors plus specific A, C, and E variances on each phenotype to account for residual variance. This explored and compared all standard etiologic hypotheses explaining the complex relationships among these internalizing constructs. LRT and AIC statistics were used to decide on the best-fitting overarching model, after which common and specific factors were removed to see if they were needed to account for the observed data.

Since the common pathway model is statistically nested within the independent pathway model (Kendler, Heath, Martin, & Eaves, 1987), they were compared for best overall fit to these data. All analyses were performed in the R software package (version 1.1.442; R Development CoreTeam, 2015) with twin analyses conducted in OpenMx (version 2.9.6; Neale et al., 2016).

3 |. RESULTS

Table 1 presents the correlational patterning within blocks of measures roughly indicating a tripartite phenotypic structure as observed in the prior study: (a) anxiety and fear (symptoms or temperament), (b) negative affect and neuroticism, and (c) behavioral activation and extraversion. That structure divided by twin pair type (monozygotic, or MZ vs. dizygotic, or DZ) provides initial insights into their rich etiological relationships. Most MZ correlations (upper triangle) exceed DZ correlations (lower triangle), suggesting a role for genetic factors within and between measures.

TABLE 1.

Cross-twin, cross-trait correlations by twin pair type for all constructs blocked by strength of correlation (N = 768)

| Twin 1/Twin 2 | ANX | AS | BI | Fear | NEUR | DEP | IRR | BA | EXTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANX | – | 0.28** | 0.25** | 0.36*** | 0.20* | 0.17 | 0.21* | −0.02 | −0.19* |

| AS | 0.34*** | – | 0.30*** | 0.43*** | 0.38*** | 0.28** | 0.24** | 0.09 | −0.08 |

| BI | 0.22*** | 0.12 | – | 0.33*** | 0.36*** | 0.27** | 0.28** | 0.14 | −0.11 |

| Fear | 0.22*** | 0.18** | 0.18** | – | 0.22* | 0.28** | 0.28** | 0.01 | −0.21* |

| NEUR | 0.24*** | 0.14* | 0.18** | 0.14* | – | 0.44*** | 0.37*** | 0.05 | −0.20* |

| DEP | 0.24*** | 0.16* | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.20** | – | 0.31*** | −0.07 | −0.19* |

| IRR | 0.22*** | 0.13 | 0.15* | 0.15* | 0.15* | 0.08 | – | 0.06 | −0.05 |

| BA | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | – | 0.11 |

| EXTR | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.07 | 0.04 | – |

Note: Upper triangle, monozygotic; lower triangle, dizygotic.

Abbreviations: ANX, anxiety; AS, anxiety sensitivity; BA, behavioral activation; BI, behavioral inhibition; DEP, depression; EXTR, extraversion; IRR, irritability; NEUR, neuroticism.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Sex was found to be a significant covariate for about half of the measures (Table S3). Thus, it was included as a definition variable in all models. Table S4 lists the series of common pathway models tested and their fit statistics. Table S5 provides the parameter estimates for the full model (Model 1). The best-fitting submodel (3a) required common AL and EL factors for each of the higher-order latent dimensions (Anxiety/Fear, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect) but no common CL effects on these. However, specific AS, CS, and ES effects were all retained, although their loadings on some measures were estimated as near zero. The results of this best-fitting model are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2 (common factors only displayed for clarity). The model estimates genetic variance AL of 31% for Anxiety/Fear, 22% for Dysphoria, and 82% for Positive Affect with the remaining proportion of common variance for each latent dimension due to individual (nonfamilial) environment EL. Those common genetic effects on the latent variables account for essentially all genetic influences on the individual measures except for fear, irritability, and behavioral activation with specific genetic variances of 9%, 7%, and 15%, respectively. Individual environmental variance specific to each measure (ES) varied in strength from 8% for neuroticism to 50% for irritability, while the influence of familial environment CS was only substantive for anxiety (9%) and depression (12%). The genetic correlation between Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria could be constrained to rA = 1, while the individual-specific environmental correlation was estimated as rE = 0.70. This analysis suggests that the early adolescent genetic influences on these dimensions are indistinguishable, while their environmental influences are more moderately correlated.

TABLE 2.

Proportion of variance in liability to internalizing phenotypes from common and specific genetic and environmental risk factors in final trivariate common pathway model

| Additive genetic factors |

Familial environmental factors |

Unique environmental factors |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent dimension or Construct | AL | As | Cs | EL | Es |

| Anxiety/Fear | 0.31 (0.22–0.40) | – | – | 0.69 (0.60–0.78) | – |

| Dysphoria | 0.22 (0.11–0.32) | – | – | 0.78 (0.68–0.84) | – |

| Positive Affect | 0.82 (0.71–0.91) | – | – | 0.18 (0.09–0.29) | – |

| Anxiety | – | – | 0.09 (<0.01–0.13) | – | 0.18 (0.13–0.22) |

| Anxiety sensitivity | – | – | 0.02 (<0.01–0.06) | – | 0.29 (0.24–0.34) |

| Behavioral inhibition | – | 0.11 (<0.01–0.18) | – | – | 0.26 (0.20–0.31) |

| Fear | – | 0.09 (<0.01–0.16) | – | – | 0.35 (0.28–0.42) |

| Neuroticism | – | – | 0.02 (0.01a–0.06) | – | 0.08 (0.05–.12) |

| Depression | – | – | 0.12 (<0.01–0.18) | – | 0.33 (0.25–0.39) |

| Irritability | – | 0.07 (<0.01–0.17) | – | -- | 0.50 (0.40–0.61) |

| Behavioral activation | – | 0.15 (<0.01–0.24) | – | – | 0.43 (0.37–0.54) |

| Extraversion | – | – | – | – | 0.10 (0.02–0.22) |

Note: Correlations between Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria latent factors: rA = 1.0; rC = N/A; rE = 0.70. Italics distinguish the Latent Dimensions from measured Constructs below in that same column.

Abbreviations: AL, latent A factor; AS, specific A factor; CS, specific C factor; EL, latent E factor; ES, specific E factor.

Lower bound indistinguishable from zero.

FIGURE 2.

Tripartite twin common pathway model. It contains six common (shared) etiologic influences: A1/E1, ANX/FEAR genetic/environmental factors; A2/E2, Dysphoria (DYSPH) genetic/environmental factors; A3/E3, Positive Affect (PA) genetic/environmental factors. For clarity, measure-specific variance sources are not shown

Given the strong genetic and environmental correlations between Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria, we tested a posthoc model that combines these into a single latent phenotype of Negative Affect. This resulting 2-factor common pathway model with uncorrelated dimensions of Negative Affect and Positive Affect did not fit as well as the final tripartite model (see Tables S6 and S7).

Tables S8 and S9 list the corresponding series of independent pathway models tested and the estimated variances for the full model, respectively. As indicated, the best-fitting model (3c) included two sets of common A and E factors and one common C factor together with specific AS and ES for each measure. Consistent with the rA = 1 finding in the common pathway model, this final model contained a single set of genetic influences (A1) common to constructs subsumed under both Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria with a separate genetic factor (A2) common to Positive Affect constructs behavioral activation and extraversion. Somewhat distinct, common nonfamilial environmental factors E1 and E2 for Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria constructs, respectively, indicate that their overall etiologic differences are mainly environmental in nature. Familial environment was captured by one common factor C1 with stronger effects on the Anxiety/Fear measures; specific C factors were minimal and could be dropped in the final model. Total genetic variance ranged from 17% for fear to 67% for extraversion, while familial environmental variance ranged from 2% for irritability to 28% for anxiety sensitivity.

Overall, independent pathway model 3c (−2LL = 38,887.08; AIC = 26,075.08) fit the data better than common pathway model 3a (−2LL = 39,094.54; AIC = 26,242.54; Tables S4 and S8). This suggests that the distribution of etiologic influences on these constructs are more nuanced than indicated by their higher-order phenotypic factor structure. Common pathways with estimated loadings <0.01 were dropped for parsimony and interpretability in final model 3ca depicted in Figure 3 (common factors only displayed for clarity). Variance components are listed in Table 3.

FIGURE 3.

Best-fit twin independent pathway model (3ca in Table S6). It contains five common (shared) etiologic influences: A1, negative valence genetic factor; A2, positive valence genetic factor; C1, overall family environmental factor; E1, overall individual-specific environmental factor; E2, dysphoric mood individual-specific environmental factor. For clarity, measure-specific variance sources are not shown

TABLE 3.

Proportion of variance in liability to internalizing phenotypes from common and specific genetic and environmental risk factors in final independent pathway model (3ca) (95% confidence intervals)

| Additive genetic factors |

Familial environmental factors |

Unique environmental factors |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | A1 | A2 | As | Total | C1 | Total | E1 | E2 | Es | Total |

| Anxiety | 0.25 (0.03–0.48) | – | 0.08 (0.04–0.13) | 0.33 | 0.25 (0.06–0.44) | 0.25 | 0.25 (0.17–0.34) | 0.02 (<0.01–0.04) | 0.16 (0.12–0.21) | 0.43 |

| Anxiety sensitivity | 0.18 (0.01–0.41) | – | – | 0.18 | 0.26 (0.08–0.41) | 0.26 | 0.31 (0.21–0.41) | – | 0.25 (0.21–0.30) | 0.56 |

| Behavioral Inhibition | 0.29 (0.08–0.45) | – | 0.07 (0.01–0.14) | 0.34 | 0.07 (<0.01–0.22) | 0.07 | 0.34 (0.23–0.47) | – | 0.22 (0.16–0.29) | 0.56 |

| Fear | 0.11 (<0.01–0.32) | – | 0.06 (<0.01–0.13) | 0.17 | 0.23 (0.09–0.36) | 0.23 | 0.28 (0.18–0.39) | – | 0.31 (0.25–0.39) | 0.59 |

| Neuroticism | 0.53 (0.32–0.64) | – | – | 0.53 | 0.03 (<0.01–0.21) | 0.03 | 0.17 (0.10–0.29) | 0.14 (0.08–0.22) | 0.12 (0.08–0.16) | 0.43 |

| Depression | 0.30 (0.10–0.46) | – | 0.12 (0.05–0.19) | 0.42 | 0.11 (0.01–0.28) | 0.11 | 0.05 (0.01–0.11) | 0.17 (0.10–0.26) | 0.24 (0.17–0.32) | 0.46 |

| Irritability | 0.22 (0.10–0.35) | – | 0.08 (<0.01–0.18) | 0.30 | 0.02 (<0.01–0.12) | 0.02 | 0.06 (0.01–0.13) | 0.18 (0.09–0.29) | 0.44 (0.33–0.55) | 0.68 |

| Behavioral activation | 0.04 (0.01–0.11) | 0.44 (0.34–0.54) | – | 0.48 | 0.03 (<0.01–0.11) | 0.03 | 0.08 (0.04–0.15) | – | 0.40 (0.31–0.50) | 0.47 |

| Extraversion | – | 0.56 (0.45–0.69) | 0.15 (0.01–0.26) | 0.71 | 0.004 (<0.01–0.03) | 0.004 | – | 0.03 (0.01–0.06) | 0.27 (0.21–0.33) | 0.30 |

Note: A1, A2, and As—common and specific additive genetic factors; C1 and Cs—common and specific familial environmental factors; E1, E2, and Es—common and specific unique environmental factors. Bolded columns designate proportion of total variance accounted for by the combined common and specific etiological sources of variance for each measure. Total columns may not add up to 1.00 across factors due to rounding error.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This community-based twin study used multivariate SEM to investigate genetic and environmental risk-factor relationships among a broad array of dimensional constructs as potential intermediate phenotypes of internalizing psychopathology in youth. Each construct has been reported in prior studies to show differences among cases of one or more IDs and unaffected comparisons. As indicated in Table 1, complex relational patterns exist among these measures in juvenile twin pairs.

We compared two multivariate SEM approaches to investigate etiologic contributions to symptoms and associated traits/constructs. The first applied the common pathway model as it relates to the previously identified tripartite dimensions representing Anxiety/Fear, Dysphoria, and Positive Affect. The result of that model finds genetic variance of 31% for Anxiety/Fear, 22% for Dysphoria, and 82% for Positive Affect with the remaining proportion of common variance for each of those latent dimensions due to nonfamilial environment. Those common genetic effects account for most of the genetic influences on the individual measures, and the genetic factors for Anxiety/Fear are highly correlated with those for Dysphoria. These results in youth parallel those of earlier twin studies in adults examining clinical symptoms (Kendler et al., 1987) and syndromes (Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath, & Eaves, 1992) of anxiety and depression. Similarly, data in adults found highly overlapping genetic influences but more modestly correlated environmental influences.

The second approach explored the space of alternative etiologic structures through a series of independent pathway models. Unlike the common pathway models, these alternative models allowed the effects of common genetic and environmental influences to differentially vary among measures both within and between the tripartite groupings (Figure 2 and Table 1). The final independent pathway model provided a better fit than the more constrained common pathway model, suggesting that etiology for internalizing psychopathology is more complex than the tripartite phenotypic factor structure would otherwise suggest. That structure consists of a single common set of genetic influences A1 on constructs associated with both Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria and a distinct genetic factor A2 for Positive Affect. Familial environment acted via a common Factor C1 that mostly strongly affected fear, anxiety, and anxiety sensitivity, while the remaining sources of variance were due to two common nonfamilial environmental factors primarily influencing constructs related to Anxiety/Fear (E1) versus Dysphoria (E2). Thus, the common familial influences (i.e., A1 and C1) mostly account for the overlap/comorbidity between anxiety and depression, while the nonfamilial environmental influences (E1 and E2) drives their differential risk. This is consistent with evidence that some life events are more anxiogenic versus depressogenic (Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1998).

To our knowledge, this is the first study in youth to jointly examine the etiologic relationships among ID symptoms and so many broadly associated, trait-like dimensions. While a hierarchical tripartite model fits the phenotypic data, the structure of the underlying etiological factors seems less well demarcated. The genetic factor A1 differentially influences expression of acute (fear) and potential (anxiety) threat response, anxious temperament (sensitivity, inhibition, neuroticism), and negative affect (depression, irritability). In other words, there is not a simple, one-to-one endophenotypic relationship between pairs of measures, but rather, a complex network of relationships among multiple constructs and symptom complexes differentially driven by a common set of genetic influences. Thus, any one of these should demonstrate a shared genetic basis with the others. This has been borne out in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of individual internalizing constructs. For example, substantial genetic correlations have been estimated between GWAS findings for neuroticism (Nagel et al., 2018) and those for major depression (Wray et al., 2018) and anxiety disorders (Otowa et al., 2016).

Prior twin studies have explored some of these relationships in subsets of the constructs examined in the current report. One study reported substantial genetic correlation between irritability and depression (Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan, & Eley, 2012), while longitudinal analyses in another found shared genetic and environmental factors between irritability and combined anxious/depressed symptoms from ages 8–9 to 19–20 (Savage et al., 2015). Studies in another developmental twin cohort reported stable genetic influences of anxiety sensitivity assessed at age 8 on various anxiety subscales at age 10 (Waszczuk, Zavos, & Eley, 2013) as well as shared genetic and environmental effects between anxiety sensitivity and symptoms of anxiety and depression both within and between ages 15 and 17 (Zavos, Rijsdijk, & Eley, 2012).

These findings should be considered in the context of several potential limitations. First, these measures were all assessed at the same time point allowing only cross-sectional analyses. Longitudinal data could inform the stability of the observed structure and potential causal pathways. Second, we applied the independent pathway model as an alternative to the common pathway model; its results need to be confirmed in an independent data set that provides similar information for modeling. Third, we evaluated the relationship between the putative endophenotypic constructs and internalizing symptoms, not disorders. Both SCARED and SMFQ have previously shown adequate validity with respect to clinically assessed IDs. Compared to a patient sample, a community sample such as VCU-JAS typically has lower severity of internalizing symptoms, making generalization to patient samples uncertain. Nonetheless, the sample is epidemiologically representative with frequencies of IDs consistent with those observed in other population-based samples of youth (Merikangas, Avenevoli, Costello, Koretz, & Kessler, 2009). Fourth, only Caucasian families were recruited into this study to minimize potential heterogeneity across populations, precluding the ability to generalize our findings to children of other racial and ethnic groups. Fifth, there are limitations inherent to psychiatric twin studies such as the equal environment assumption (Kendler, 1993).

The results of this study have broad implications for future research into developmental risk factors for IDs and their etiologic classification. With a single overarching set of genetic influences on Anxiety/Fear and Dysphoria constructs in developing children, our findings support the conceptual organization of a latent Negative Valence System (NVS) domain as proposed by RDoC. NVS broadly subsumes constructs associated with threat responses like fear and anxiety and dysphoric mood states like irritability. Our results suggest the potential value of expanding future investigations to include trait-like endophenotypes to understand their developmental roles. Thus, rather than focus on individual diagnostic syndromes, more comprehensive studies might transdiagnostically examine the shared versus specific aspects of genetically related constructs, particularly across anxiety and depressive phenotypes in youth. Research investigating “the general factor of psychopathology” (p-factor) (Caspi & Moffitt, 2018; Smith, Atkinson, Davis, Riley, & Oltmanns, 2020) has typically examined broader categories of mental illness (internalizing, externalizing, and psychosis) with more recent efforts that include aspects of personality (Rosenstrom et al., 2019) and temperament (Class et al., 2019; Hankin et al., 2017). Some studies have begun to incorporate measured genetic variants (Allegrini et al., 2020; Riglin et al., 2019). Use of more powerful multivariate approaches like SEM that model the factor structure of closely related phenotypes directly with genetic variants (e.g., GW-SEM; Verhulst, Maes, & Neale, 2017) could further clarify the complex picture of widespread genetic correlation observed among GWAS of various psychiatric phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

VCU-JAS was sponsored through the first RDoC funding request (RFA-MH-12-100) and funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01MH098055 to JMH and NIMH-IRP-ziamh002781 to DSP). CS was supported by T32 MH020030 (PI: M. Neale). JLB was supported by NIMH T32MH020030 and NIDA T32DA015035 (m/PI: R. Cunningham-Williams, K. K. Bucholz). The Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry was supported through the NIH Center for Advancing Translational Research Grant Number UL1TR000058.

Funding information

National Institute of Mental Health, Grant/Award Numbers: NIMH-IRP-ziamh002781, R01MH098055

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data from consented subjects participating in this study have been deposited into RDoCdb/NDA (Collection C2131).

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this study comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- Akaike H (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Allegrini AG, Cheesman R, Rimfeld K, Selzam S, Pingault JB, Eley TC, & Plomin R (2020). The p factor: Genetic analyses support a general dimension of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 61(1), 30–39. 10.1111/jcpp.13113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Hope DA (2008). A review of the tripartite model for understanding the link between anxiety and depression in youth. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(2), 275–287. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, & Silver D (1995). The development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. InternationalJournal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, & Neer SM (1997). The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 545–553. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9100430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, van Beijsterveldt CE, & Hudziak JJ (2005). Genetic and environmental influences on anxious/depression during childhood: A study from the Netherlands Twin Register. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 4(8), 466–481. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney DM, Moroney E, Machlin L, Hahn S, Savage JE, Lee M, … Hettema JM (2016). The twin study of negative valence emotional constructs. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 19(5), 456–464. 10.1017/thg.2016.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS,&White TL (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2018). All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 831–844. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Class QA, Van Hulle CA, Rathouz PJ, Applegate B, Zald DH, & Lahey BB (2019). Socioemotional dispositions of children and adolescents predict general and specific second-order factors of psychopathology in early adulthood: A 12-year prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(6), 574–584. 10.1037/abn0000433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SB (1965). A new scale for personality measurements in children. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 35(3), 362–367. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5850445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint J, Timpson N, & Munafo M (2014). Assessing the utility of intermediate phenotypes for genetic mapping of psychiatric disease. Trends in Neurosciences, 37(12), 733–741. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, & Gould TD (2003). The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(4), 636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood TA, Lazzeroni LC, Maihofer AX, Swerdlow NR, Calkins ME, Freedman R, … Braff DL (2019). Genome-wide association of endophenotypes for schizophrenia from the consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia (COGS) study. JAMA Psychiatry, 76, 1274 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Davis EP, Snyder H, Young JF, Glynn LM, & Sandman CA (2017). Temperament factors and dimensional, latent bifactor models of child psychopathology: Transdiagnostic and specific associations in two youth samples. Psychiatry Research, 252, 139–146. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, … Wang P (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(7), 748–751. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS (1993). Twin studies of psychiatric illness. Current status and future directions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(11), 905–915. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8215816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Heath AC, Martin NG, & Eaves LJ (1987). Symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression. Same genes, different environments? Archives of General Psychiatry, 44(5), 451–457. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3579496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, & Prescott CA (1998). Stressful life events and major depression: Risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186(11), 661–669. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9824167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, & Neale MC (2010). Endophenotype: A conceptual analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(8), 789–797. 10.1038/mp.2010.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, & Eaves LJ (1992). Major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Same genes, (partly) different environments? Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(9), 716–722. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1514877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, & Neale MC (2003). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(9), 929–937. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12963675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15939837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, … Zimmerman M (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454–477. 10.1037/abn0000258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF (1999). The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(10), 921–926. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10530634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Van HC, Urbano RC, Krueger RF, Applegate B, … Waldman ID (2008). Testing structural models of DSM-IV symptoms of common forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(2), 187–206. 10.1007/s10802-007-9169-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb DJ, Middeldorp CM, van Beijsterveldt CE, Bartels M, van der Aa N, Polderman TJ, & Boomsma DI (2010). Heritability of anxious-depressive and withdrawn behavior: Age-related changes during adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(3), 248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Aggen SH, Carney DM, Hahn S, Moroney E, Machlin L, … Hettema JM (2017). Latent structure of negative valence measures in childhood. Depression and Anxiety, 34(8), 742–751. 10.1002/da.22656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley EC, & Silberg JL (2013). The mid-atlantic twin registry, revisited. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(1), 424–428. 10.1017/thg.2012.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Koretz D, & Kessler RC (2009). National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(4), 367–369. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819996f1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, & Clark LA (1998). Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 377–412. 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, de Leeuw CA, Bryois J, … Posthuma D (2018). Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nature Genetics, 50(7), 920–927. 10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, & Cardon LR (1992). Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers B.V. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Hunter MD, Pritikin JN, Zahery M, Brick TR, Kirkpatrick RM, … Boker SM (2016). OpenMx 2.0: Extended structural equation and statistical modeling. Psychometrika, 81(2), 535–549. 10.1007/s11336-014-9435-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH (1983). Reliability and validity of the revised fear surgery schedule for children (FSSC-R). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(6), 685–692. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6661153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otowa T, Hek K, Lee M, Byrne EM, Mirza SS, Nivard MG, … Hettema JM (2016). Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Molecular Psychiatry, 21, 1391–1399. 10.1038/mp.2015.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, & Ma Y (1998). The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(1), 56–64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9435761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development CoreTeam. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org

- Riglin L, Thapar AK, Leppert B, Martin J, Richards A, Anney R, … Thapar A (2019). Using genetics to examine a general liability to childhood psychopathology. Behavior Genetics, 10.1007/s10519-019-09985-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstrom T, Gjerde LC, Krueger RF, Aggen SH, Czajkowski NO, Gillespie NA, … Ystrom E (2019). Joint factorial structure of psychopathology and personality. Psychological Medicine, 49(13), 2158–2167. 10.1017/s0033291718002982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Verhulst B, Copeland W, Althoff RR, Lichtenstein P, & Roberson-Nay R (2015). A genetically informed study of the longitudinal relation between irritability and anxious/depressed symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 377–384. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage JE, Sawyers C, Roberson-Nay R, & Hettema JM (2016). The genetics of anxiety-related negative valence system traits. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, 174, 156–177. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Atkinson EA, Davis HA, Riley EN, & Oltmanns JR (2020). The general factor of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16, 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071119-115848 [published online ahead of print February 4, 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, Razdan V, Muhrer E, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2012). The Affective Reactivity Index: A concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 53(11), 1109–1117. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02561.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, & Eley TC (2012). Adolescent irritability: Phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(1), 47–54. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst B, Maes HH, & Neale MC (2017). GW-SEM: A statistical package to conduct genome-wide structural equation modeling. Behavior Genetics, 47, 345–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waszczuk MA, Zavos HM, & Eley TC (2013). Genetic and environmental influences on relationship between anxiety sensitivity and anxiety subscales in children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(5), 475–484. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waszczuk MA, Zavos HM, Gregory AM, & Eley TC (2016). The stability and change of etiological influences on depression, anxiety symptoms and their co-occurrence across adolescence and young adulthood. Psychological Medicine, 46(1), 161–175. 10.1017/s0033291715001634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilks SS (1938). The large sample distribution of the likelihood ratio for testing composite hypotheses. Ann Math Statist, 9, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Krueger RF, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, & Koenen KC (2010). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the genetic structure of comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(2), 320–330. 10.1037/a0019035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M, Trzaskowski M, Byrne EM, Abdellaoui A, … Sullivan PF (2018). Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nature Genetics, 50(5), 668–681. 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavos HM, Rijsdijk FV, & Eley TC (2012). A longitudinal, genetically informative, study of associations between anxiety sensitivity, anxiety and depression. Behavior Genetics, 42(4), 592–602. 10.1007/s10519-012-9535-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.