Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

Amendments from Version 1 Introduction, clarified on paragraph three: two studies referenced in the background used same participants from Tanzania to evaluate effect of admission diagnosis and levels of hemoglobin on post-discharge mortality respectively. Methods, Study settings: Paragraph 1 and 2; Added details of the common admission diagnosis for children 1 to 59 admitted at KCH. Provided more details of enumeration in the KHDSS and measures for improving data quality. Statistical methods: Explained how anthropometric measurements and systematically collected laboratory tests missing values were handled in the analysis and referenced a new table (Extended data Table S1) with list of variables missing data. Results, Post-discharge mortality: Paragraph 1; Provided a summary of where the 89 post-discharge deaths occurred and causes of deaths for 26 deaths that occurred during readmission at KCH (Extended data Table S6, new table added). Paragraph 2; Provided results of proportion of children who absconded from hospital. Replaced Figure 2 with a new one that includes 95% confidence intervals. Discussion, Paragraph 1: explained the results on association of epilepsy/convulsion with inpatient mortality. Paragraph 2: Explained the post-discharge mortality rate in reference to background mortality within KHDSS and causes of deaths estimated from verbal autopsies in KHDSS. Last paragraph: Added unavailable causes of deaths among those children who died in community or other health facilities as a study limitation. Any further responses from the reviewers can be found at the end of the article.

Abstract

Background: Far less is known about the reasons for hospitalization or mortality during and after hospitalization among school-aged children than among under-fives in low- and middle-income countries. This study aimed to describe common types of illness causing hospitalisation; inpatient mortality and post-discharge mortality among school-age children at Kilifi County Hospital (KCH), Kenya.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study of children 5−12 years old admitted at KCH, 2007 to 2016, and resident within the Kilifi Health Demographic Surveillance System (KHDSS). Children discharged alive were followed up for one year by quarterly census. Outcomes were inpatient and one-year post-discharge mortality.

Results: We included 3,907 admissions among 3,196 children with a median age of 7 years 8 months (IQR 74−116 months). Severe anaemia (792, 20%), malaria (749, 19%), sickle cell disease (408, 10%), trauma (408, 10%), and severe pneumonia (340, 8.7%) were the commonest reasons for admission. Comorbidities included 623 (16%) with severe wasting, 386 (10%) with severe stunting, 90 (2.3%) with oedematous malnutrition and 194 (5.0%) with HIV infection. 132 (3.4%) children died during hospitalisation. Inpatient death was associated with signs of disease severity, age, bacteraemia, HIV infection and severe stunting. After discharge, 89/2,997 (3.0%) children died within one year during 2,853 child-years observed (31.2 deaths [95%CI, 25.3−38.4] per 1,000 child-years). 63/89 (71%) of post-discharge deaths occurred within three months and 45% of deaths occurred outside hospital. Post-discharge mortality was positively associated with weak pulse, tachypnoea, severe anaemia, HIV infection and severe wasting and negatively associated with malaria.

Conclusions: Reasons for admissions are markedly different from those reported in under-fives. There was significant post-discharge mortality, suggesting hospitalisation is a marker of risk in this population. Our findings inform guideline development to include risk stratification, targeted post-discharge care and facilitate access to healthcare to improve survival in the early months post-discharge in school-aged children.

Keywords: Mortality, Inpatient, Post-discharge, Reason for admission, School-aged children, Cohort, Africa

Introduction

Despite a remarkable decline in global child mortality, more than 6 million children died in 2018, of which 0.9 million (15%) deaths occurred among children aged 5 to 14 years, mostly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) 1, 2. Public health efforts to improve survival are generally directed towards children <5 years old 2– 4. Despite there being no specific new health interventions targeting children aged 5 to 14 years, their mortality risk from 1990 to 2016 declined by 51% globally 4. However, since 2000, the annual rate of mortality reduction in this group (2.7%) has been lower than amongst children <5 years old (4.0%) 4.

Children ≥5 years old may be admitted to hospital with different conditions than younger children and their risks for inpatient or post-discharge mortality may also differ. However, there are only limited data describing reasons for admission and mortality-patterns in LMICs. Among school-aged children admitted to six Kenyan hospitals in 2013, 3.5% of children aged 5 to 9 years and 5.0% of children 10 to 14 years died 5. Infectious diseases such as malaria were the main reported causes of death in children ≥5 years 2, 5, 6.

Post-discharge mortality is increasingly recognized as a significant contributor to the burden of mortality among under-fives in LMICs and adults in resource-rich settings 7– 9. The most recent systematic review (2018) of paediatric post-discharge mortality in LMICs did not identify any studies focusing specifically on school-aged children 7, 8. Of 24 studies reviewed, four included children ≥5 years old. A study in Bangladesh with a sample size of 74 children aged 24 to 72 months did not report the number of children who were ≥5 years old 10. A large study in Kenya among children 0 to 15 years old (N=14,971) reported that 16% (88/535) of all post-hospital discharge deaths were among children aged 5 to 14 years 11 and two studies from Uganda with children aged 2 months to 12 years reported ~1% and 3.8% children dying after discharge, respectively, but were not disaggregated by age group 12, 13. Since the latest systematic review (2018) 7, four more studies have evaluated paediatric post-discharge mortality in LMICs 3, 14– 16. Hau et al. included children aged 2 to 12 years followed-up for 12 months after discharge from two hospitals in Tanzania and found that 16% (26/161) of children aged 5 to 12 years died after hospital discharge 3. Post-discharge mortality risk was reported to be higher than that of children <5 years (hazard ratio 2.44 (95%CI, 1.37 to 4.34) 3. The commonest diagnoses at admission were malaria and sickle cell disease 3. The second study from southern Mozambique included 18,023 children aged <15 years, of which 83/3,816 (2.2%) aged ≥5 years died within three months after discharge 14. The third study was from Kenya, but excluded children ≥5 years old 15. The fourth study from Tanzania included children aged 2 to 12 years, of whom 47/466 (10%) died one year after hospital discharge, but deaths were not disaggregated by age 16. Two of the four studies from Tanzania, used same study participants to evaluate overall one-year post-discharge mortality based on admission diagnosis 3 and on levels of haemoglobin 16 respectively.

In this retrospective cohort study, we aimed to describe the reasons for hospitalisation, underlying illnesses, and the clinical characteristics and features associated with mortality during hospitalisation and for one year after discharge among children 5 to 12 years old admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at Kilifi County Hospital (KCH), located on the Indian Ocean coast in Kenya. KCH is a secondary care hospital handling approximately 5,000 annual paediatric admissions. At KCH, approximately 60% of paediatric admissions are aged 1 to 59 months, who are mostly admitted and treated for pneumonia and diarrhoea 15, 17, 18. Most of the population served by the hospital are rural farmers. Clinical care at the hospital follows Kenyan and World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

Systematic data including clinical signs, anthropometry and laboratory investigations at admission have been collected by research clinicians and entered in a database since 1998. At discharge or death, up to two final diagnoses are assigned by the discharging clinician. From 2002, approximately 250,000 residents in an area of 891 km 2 neighbouring KCH have been enumerated every four months by the Kilifi Health and Demographic Surveillance System (KHDSS) for births, deaths and in- or out-migration 19. During each enumeration round, data collectors move from one household to another using GIS-derived maps and ask pre-specificized questions to the head of household and other members as described elsewhere 19. Data on admissions to KCH are linked to the KHDSS population database by matching individual child using unique ID number through predesigned database query programme. Both the KCH admissions and KHDSS databases are programmed with validation checks to improve data quality. Community enumerators within the KHDSS, clinicians and clinical assistants collecting data in the KHDSS and KCH respectively are regularly trained.

Study population

Children aged 60 to 155 months admitted to KCH between 2007 and 2016 and resident within the KHDSS were included. The post-discharge analysis included all children discharged alive. Data from the KHDSS up to the 2018 August census round were used to confirm vital status post-discharge.

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study. Exposures evaluated were clinical and demographic features, anthropometry and laboratory variables at admission. Outcomes examined were inpatient and one-year post-discharge mortality.

Data sources/measurement

Anthropometry, clinical history and examination, complete blood count, HIV antibody test, blood smear for malaria and blood culture were systematically conducted at admission as previously described 20. Anthropometry was taken by trained clinical assistants: mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) using a non-stretchable insertion tape (TALC, St Albans, UK), weight using an electronic scale (Seca 825, Birmingham, UK) and height using a stadiometer (Seca 215, Birmingham, UK) which were regularly checked for consistency. HIV antibody testing used two rapid tests (Determine; Inverness Medical, Fl, USA; and Unigold; Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland). Caregivers of children with a positive HIV antibody test were counselled and referred to an HIV comprehensive care clinic. Details of subsequent outpatient clinic attendance and antiretroviral treatment were not recorded on the database. Children found to have malnutrition, sickle cell disease, tuberculosis, cardiac or neurological conditions were referred to outpatient clinics for continued care.

For this analysis, malaria was defined as a blood smear positive for Plasmodium falciparum and anaemia was defined as moderate (haemoglobin 8 to 11.4 g/dl) or severe (haemoglobin <8g/dl), as per WHO guidelines 21. Biochemical tests, radiology, sickle cell testing, lumbar puncture and other investigations were done at the discretion of the treating clinician. Meningitis was diagnosed using the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination and culture as follows: positive culture for known pathogen, positive CSF microscopy (Gram stain and/or Indian ink stain), positive antigen test ( S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae type B, N. meningitidis, and C. neoformans) and CSF white blood cell count (WBC) ≥10 cells/µl.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA (version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All eligible admissions and discharges from the population of KCH residents of KHDSS within the study period were included in the study, therefore, no formal sample size estimation was conducted.

MUAC-for-age z-score (MUACZ) were calculated using the method of Mramba et al. 22. Body mass index-for-age z-score (BMIZ), weight-for-age (WAZ) and height-for-age z-score (HAZ) were calculated using WHO 2007 growth references and classified as normal (≥-2Z), moderate (-3 to -2Z) and severe (<-3Z) 23. Anthropometric measurements and systematically collected laboratory tests were regarded as missing not at random ( Extended data Table S1). To ensure all children were included in the multivariable regression models, we used categorical variables and included a ‘missing’ category in the analysis.

Because the children could be admitted more than once during the study period, for the analysis of inpatient deaths we performed a multiple-admission analysis where each child could contribute more than one admission record using their unique person IDs. To examine features at admission associated with inpatient mortality, we used a backward stepwise log-binomial regression model with robust standard errors to account for multiple admissions retaining variables with a P-value <0.1 and reported adjusted risk ratios for variables with P-value <0.05 in the final multivariable model.

To calculate the post-discharge mortality rate, time at risk was defined as the date of hospital discharge until death, out-migration or 365 days later. We performed a multiple-discharge analysis where children with multiple admissions with live discharge contributed separate person-time periods when there was no overlap during the one-year follow-up. After assessing and confirming the proportional hazard assumption was not violated using the Schoenfeld residuals test, we used a Cox proportional hazard regression model with robust standard errors to account for multiple discharges to examine admission features associated with post-discharge mortality.

For both inpatient and post-discharge regression analysis, individual clinical signs, laboratory tests and final diagnoses assigned by clinical staff were used for diagnoses not captured by syndromic definitions using clinical signs. In the regression models, we used MUACZ to define undernutrition rather than BMIZ because MUACZ predicts mortality as effectively as BMIZ 22, is less affected by dehydration than weight-based measures 24, and fewer children were missing MUAC measurements. We initially excluded biochemical features that were not systematically collected and performed exploratory analyses of these features. We tested if the effects of HIV status, anaemia and malaria were modified by age and if the malaria effects on post-discharge mortality were modified by anaemia or nutritional status using likelihood-ratio tests. Goodness-of-fit of the multivariable regression models was assessed using the area under receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) and internally validated using the bootstrapping method with 1000 resampling with replacement 25.

Ethical statement

The Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) National Ethics Review Committee (SCC 2778) approved the study. Written consent for the children’s participation in the original study was provided by their parents/guardians, which included consent for subsequent analyses.

Results

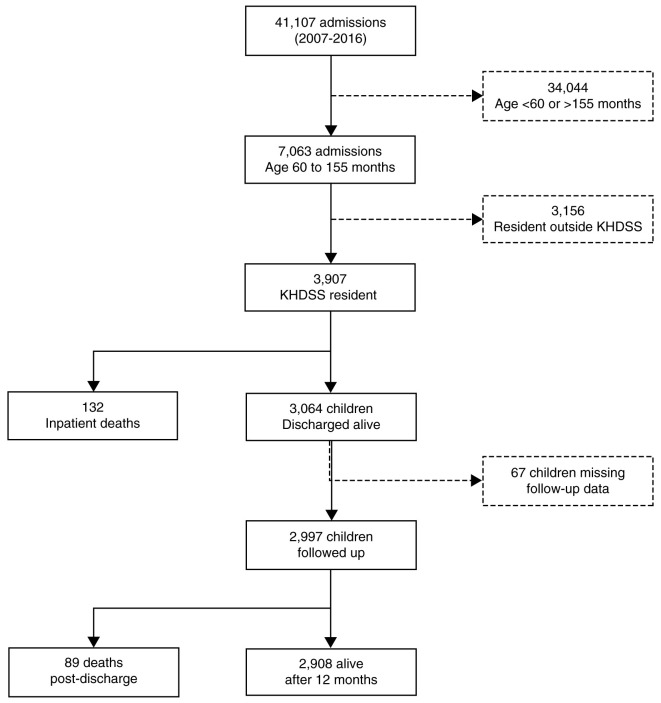

From 2007 to 2016, there were 41,107 paediatric admissions to KCH, of which 7,063 (17%) were aged 5 to 12 years ( Figure 1). Of these, 3,907 (55%) admissions among 3,196 children were KHDSS residents and were included in this analysis ( Figure 1). Their median age was 92 (IQR 74−116) months and 1,673 (43%) were female. Of the 3,907 admissions, 792 (20%) presented with severe anaemia, 749 (19%) with malaria, 408 (10%) with sickle cell disease (known at admission or diagnosed during admission), 408 (10%) had suffered trauma, 340 (8.7%) with severe pneumonia and 194 (5.0%) with diarrhoea.

Figure 1. Study participant recruitment and follow-up.

KHDSS, Kilifi Health Demographic Surveillance System.

Underlying chronic conditions included stunting in 1,143 (29%), severe stunting in 90 (2.3%), severe wasting (MUACZ <-3) in 623 (16%), HIV infection in 194 (5.0%), and nutritional oedema in 90 (2.3%) ( Table 1, Table 2 and Extended data Table S2).

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics at admission to hospital.

| Admission characteristics (N=3,907) | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age in months, median (IQR) | 92 (74−116) |

| Sex (female) | 1673 (43) |

| Had been admitted prior to age 5 years,

before this study |

1152 (29) |

| Clinical features | |

| Axillary temp <36°C | 238 (6·1) |

| Axillary temp 36 to 37.5°C | 2009 (51) |

| Axillary temp >37.5°C | 1660 (43) |

| Respiratory rate <20 breaths per min | 80 (2.1) |

| Normal respiratory rate | 2179 (56) |

| Respiratory rate >30 breaths per min | 1580 (40) |

| Subcostal indrawing | 249 (6.4) |

| History of breathing difficulty | 432 (11) |

| Hypoxia (SaO 2 <90%) | 130 (3.3) |

| Heart rate <80 beats per min | 156 (4.0) |

| Normal heart rate | 1694 (43) |

| Heart rate >120 beats per min | 2035 (52) |

| Capillary refill >2 seconds | 98 (2.5) |

| Temperature gradient | 152 (3.9) |

| Weak pulse | 85 (2.2) |

| Lethargy | 417 (11) |

| Sunken eyes | 132 (3.4) |

| Reduced skin turgor | 71 (1.8) |

| Impaired consciousness * | 540 (14) |

| Severe pneumonia | 340 (8.7) |

| Diarrhoea | 194 (5.0) |

| Nutritional status | |

| Nutritional oedema | 90 (2.3) |

| MUAC-for-age z-score (sd) | -1.89 (1.5) |

| BMI-for-age z-score (sd) | -1.37 (1.2) |

| Height-for-age z-score (sd) | -1.46 (1.3) |

| Weight-for-age z-score (sd) | -1.81 (1.2) |

| Laboratory investigations | |

| HIV infected | 194 (5.0) |

| Malaria smear positive | 749 (19) |

| Anaemia | |

| None (haemoglobin ≥11.5g/dl) | 817 (21) |

| Moderate (haemoglobin 8 to 11.4g/dl) | 1497 (38) |

| Severe (haemoglobin <8g/dl) | 792 (20) |

| Bacteraemia | 138 (3.5) |

| Meningitis | 54 (1.4) |

*Defined as presence of prostration or coma. MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; BMI, body mass index; sd, standard deviation. 49 (1.3%) records missing MUAC, 442 (11%) records missing BMI, 287 (7.3%) records missing height-for-age z-score, 881 (23%) records missing weight-for-age z-score, 22 (0.6%) records missing heart rate, 68 (1.7%) records missing respiratory rate.

Table 2. Diagnoses assigned at discharge or death.

| Discharge diagnosis

(N=3,907) |

No. (%) Diagnosis one * | No. (%) Diagnosis two * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All

admissions (N=3,907) |

Inpatient

Deaths (N=132) |

All

admissions (N=3,907) |

Inpatient

Deaths (N=132) |

|

| Malaria | 793 (20) | 32 (4.0) | 41 (1.1) | 4 (9.8) |

| Sickle cell disease | 408 (10) | 10 (2.5) | 94 (2.4) | 5 (5.3) |

| Trauma/fractures/accidents | 408 (10) | 6 (1.5) | 23 (0.6) | 1 (4.3) |

| Anaemia | 234 (6.0) | 9 (3.8) | 254 (6.5) | 14 (5.5) |

| Epilepsy/convulsions | 198 (5.1) | 2 (1.0) | 148 (3.8) | 2 (1.4) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 196 (5.0) | 5 (2.6) | 76 (2.0) | 2 (2.6) |

| Snake bite | 179 (4.6) | 0 | 1 (0.03) | 0 |

| Cellulitis/pyomyositis | 110 (2.8) | 0 | 24 (0.6) | 0 |

| Gastroenteritis | 110 (2.8) | 0 | 28 (0.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 76 (2.0) | 0 | 38 (1.0) | 0 |

| Burns | 75 (1.9) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (0.05) | 0 |

| Elective surgery | 75 (1.9) | 0 | 9 (0.2) | 0 |

| Malnutrition | 73 (1.9) | 1 (1.4) | 34 (0.9) | 5 (15) |

| Acute abdomen | 69 (1.8) | 3 (4.3) | 4 (0.1) | 0 |

| Immunosuppression | 53 (1.4) | 8 (15) | 114 (2.9) | 12 (11) |

| Meningitis | 48 (1.2) | 12 (25) | 6 (0.2) | 1 (17) |

| Diabetes | 44 (1.1) | 0 | 3 (0.08) | 0 |

| Encephalopathy | 44 (1.1) | 5 (11) | 11 (0.3) | 3 (27) |

| Others | 649 (17) ‡ | 38 (5.9) § | 225 (5.8) ¶ | 18 (8.0) # |

| None specified | 65 (1.7) | 0 | 2,775 (71) | 65 (2.3) |

*Clinicians assign up to two diagnoses at death or discharge.

‡Cholera-12, rabies-9, measles-10, tetanus-15, osteomyelitis-20, asthma-44, empyema-3, pleural effusion-3, nephrotic syndrome-52, cerebral palsy-14, pyogenic arthritis-9, congenital disease-32, encephalophaty-44, hydrocephalus-5, acute flaccid paralysis-5, skin disease-19, arthritis-25, poisoning-43, unclassified disease-142, Burkitt’s lymphoma-2, dental-3, septicaemia-37, viral infection-14, urinary tract infection-22, viral hepatitis-25, pulmonary tuberculosis-20, otitis media-4, chickenpox-6, genital problems-5, conjunctivitis-5.

§Immunosuppression-8, septicaemia-6, pulmonary tuberculosis-5, rabies-5, tetanus-3, heart diease-6, cerebral palsy-1, hydrocephalus-1, Burkitt’s lymphoma-1, viral hepatitis-1, chickenpox-1.

¶Cholera-4, tetanus-3, oesteomyelitis-3, asthma-15, empyema-3, pleural effusion-4, nephrotic syndrome-15, cerebral palsy-16, chromosomal abnormality-2, heart disease-13, developmental delay-5, skin disease-12, poisoning-3, unclassified disease-20, septicaemia-34, conjunctivitis-6, urinary tract infection-18, renal failure-14, viral hepatitis-8, pulmonary tuberculosis-16, otitis media-6, chickpox-3, genital problems-2, no second diagnosis-2775.

#Empyema-1, cerebral palsy-1, chromosomal abnormality-1, unclassified disease-3, septicaemia-7, renal failure-3, pulmonary tuberculosis-1, chickenpox-1.

A total of 138 (3.5%) children had detectable bacteraemia ( Table 1). The commonest bacteria isolated were: Streptococcus pneumoniae (47/138, 34%), Staphylococcus aureus (32/138, 23%) and non-typhi Salmonella species (21/138, 15%) ( Extended data Table S3). The final diagnoses assigned by clinicians are shown in Table 2.

There were 132 (3.4%) inpatient deaths. The median (IQR) time to inpatient death was one (1−4) days, while median (IQR) time to discharge among the survivors was three (2−6) days. There were 44 (5.6%), 30 (4.0%), 45 (13%), 23 (17%), 9 (17%), and 10 (5.2%) deaths among those admitted with severe anaemia, malaria, severe pneumonia, bacteraemia, meningitis and diarrhoea, respectively. There were 21 (11%), 34 (5.5%), 10 (2.5%) and 4 (1.2%) deaths among children who were HIV-infected, severely wasted, had sickle cell disease and Epilepsy/convulsion, respectively ( Table 2 and Extended data Table S2).

Factors associated with inpatient mortality

In the multivariable model, older age, signs of disease severity (tachypnoea, history of breathing difficulty, weak pulse and impaired consciousness), HIV infection, bacteraemia and severe stunting were positively associated with inpatient mortality, whilst epilepsy/convulsions were negatively associated with inpatient mortality ( Table 3). All variables tested in univariable analysis are shown in Extended data Table S4. Being severely wasted was associated with inpatient death in the univariable model, but the effect was attenuated in the multivariable model ( Extended data Table S4). There was no evidence that the effect of HIV infection on inpatient mortality was modified by age (P=0.13), severe wasting (P=0.97), malaria (P=0.34) or moderate and severe anaemia (P=0.13). We found no evidence that anaemia (P=0.16), age (P=0.21) or severe wasting (P=0.14) modified the effect of malaria on inpatient mortality.

Table 3. Multivariable regression analysis of factors associated with inpatient and post-discharge mortality.

| Inpatient analysis | Post-discharge analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted RR (95%

CI) |

P-value | Adjusted HR

(95% CI) |

P-value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age in years | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | 0.04 | - | - |

| Clinical features at admission | ||||

| Respiratory rate per minute | ||||

| <20 | 2.03 (0.78 to 5.29) | 0.15 | - * | - |

| 20 to 30 | Reference | Reference | ||

| >30 | 2.21 (1.41 to 3.47) | 0.001 | 1.72 (1.12 to 2.63) | 0.01 |

| History of breathing difficulty | 2.07 (1.40 to 3.06) | <0.001 | ||

| Weak pulse | 2.18 (1.30 to 3.65) | 0.003 | 3.54 (1.64 to 7.64) | 0.001 |

| Impaired consciousness | 5.51 (3.76 to 8.10) | <0.001 | ||

| Assigned diagnosis at discharge/death | ||||

| Epilepsy/convulsions | 0.30 (0.12 to 0.73) | <0.001 | - | - |

| Investigations at admission | ||||

| HIV infected | 1.75 (1.08 to 2.85) | 0.02 | 3.06 (1.69 to 5.54) | <0.001 |

| Malaria slide positive | - | - | 0.43 (0.20 to 0.93) | 0.03 |

| Anaemia | ||||

| None | - | - | Reference | |

| Moderate | - | - | 1.38 (0.73 to 2.61) | 0.33 |

| Severe | - | - | 2.34 (1.18 to 4.63) | 0.02 |

| Bacteraemia | 3.69 (2.23 to 6.10) | <0.001 | - | - |

| Nutritional status at admission | ||||

| MUAC-for-age Z score | ||||

| ≥-2 | - | - | Reference | |

| -3 to -2 | - | - | 1.66 (0.95 to 2.91) | 0.08 |

| <-3 | - | - | 3.74 (2.24 to 6.25) | <0.001 |

| Missing | - | - | 4.99 (1.47 to 17.0) | 0.01 |

| HAZ-for-age Z score | ||||

| ≥-2 | Reference | |||

| -3 to -2 | 0.88 (0.54 to 1.44) | 0.62 | - | - |

| <-3 | 2.04 (1.30 to 3.20) | 0.002 | - | - |

| Missing | 1.71 (1.06 to 2.76) | 0.03 | - | - |

| Model performance | ||||

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.88) | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.81) | ||

| Bootstrap AUC (95% CI) | .85 (0.81 to 0.89) | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.81) | ||

Variables are included in this table if they were selected through the backward step-wise approach and have adjusted P<0.05 for either inpatient or post-discharge analysis. All variables considered in the regression models are shown in the univariable analysis models (Table S4). MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; HAZ, height-for-age z-score; AUC, area under receiver operating characteristics; RR, risk ratio from the log-binomial regression model; HR, hazard ratio from Cox proportion regression model, the global Schoenfeld residuals test for proportional hazard assumption P-value=0.11. *Insufficient numbers.

In exploratory analysis including biochemical variables, hyperkalaemia and elevated creatinine were associated with inpatient mortality ( Extended data Table S5).

Post-discharge mortality

Among the 3,064 children who were discharged alive, follow-up data were missing for 67 (2.2%) children ( Figure 1). We therefore analysed data from 2,997 children who accrued 2,853 child-years of observation. Eighty-nine (3.0%) children died during follow-up; 63 (71%), 80 (90%) and 84 (94%) of post-discharge deaths occurred within three, six and nine months of discharge, respectively. The overall mortality rate was 31.2 (95%CI, 25.3 to 38.4) per 1,000 child-years. During the first three, six and nine months after discharge, mortality rate was 244 (95%CI, 190.3 to 311.8), 89.6 (95%CI, 72.0 to 111.6), and 53.2 (95%CI, 43.0 to 65.9) per 1000 child-years, respectively. Forty (45%) deaths occurred at home, 26 (29%) during readmission to KCH and 23 (26%) in other health facilities. Among the 26 deaths at KCH, the leading estimated causes of death were: malaria (8, 31%), anaemia (3, 12%) and heart disease (3, 12%) ( Extended data Table S6).

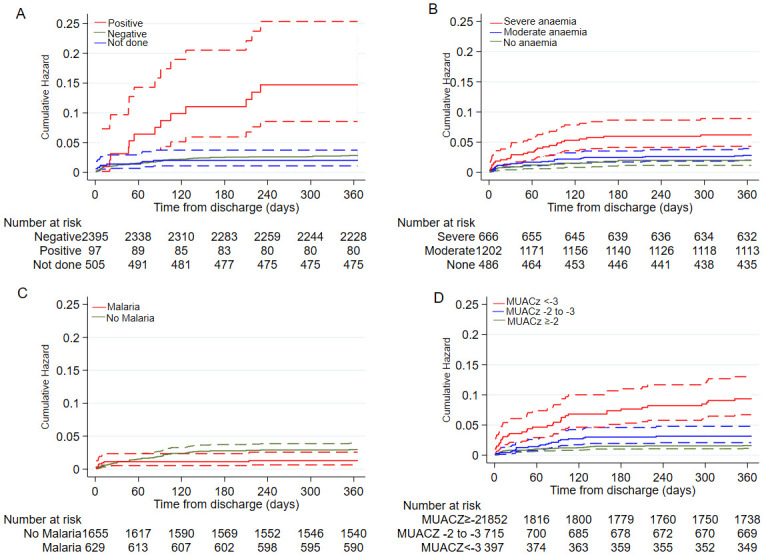

Some signs of disease severity at admission (elevated respiratory rate and presence of weak pulse), HIV infection, severe anaemia and severe wasting were positively associated with post-discharge death ( Table 3 and Figure 2). Malaria was negatively associated with post-discharge death ( Table 3 and Figure 2). Hospital admission duration was not independently associated with post-discharge death ( Extended data Table S4). Thirteen (0.43%) children absconded from hospital and all of them were alive after one year post-discharge.

Figure 2. Cumulative hazard curves for post-discharge mortality:

A) by HIV status; B) by anaemia categories; C) by malaria status and D) by mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC)-for-age z-scores groups. The broken lines are 95% confidence intervals, where there is overlap in 95%CI some lower or upper confidence intervals may not be visible.

There was no evidence that the effect of HIV infection on post-discharge mortality was modified by age (P=0.95), anaemia (P=0.25), malaria (P=0.37) or severe wasting (P=0.88). The effect of malaria on post-discharge mortality was not modified by anaemia (P=0.33) but was modified by severe wasting (P=0.007) and weak evidence of being modified by age (P=0.05). Compared to MUACZ ≥-2 with a negative malaria slide, the groups of MUACZ -3 to -2 with a negative malaria slide (HR 3.60 [95%CI, 1.75 to 7.39]) and MUACz<-3 with a negative malaria slide (HR 6.36 [95%CI, 3.10 to 13.1]) had greater post-discharge mortality. Among children with positive slide results, MUACZ was not associated with post-discharge mortality.

In the exploratory analysis of biochemical variables, hyperkalaemia and elevated creatinine were associated with post-discharge mortality ( Extended data Table S7).

Discussion

In this large study of school-aged children admitted to hospital and systematically followed-up during admission and for one year after discharge, we observed that anaemia, malaria, sickle cell disease and trauma were the leading reasons for admission. This profile is unlike that reported among under-fives, in whom pneumonia and diarrhoea are the leading reasons for admission, accounting for more than two-thirds of hospital admission in Kenya and South Africa 26– 28. All-cause inpatient case fatality was 3.4%, which was similar to the 3.5% previously reported in six hospitals in Kenya among children 5 to 17 years old in 2013 5. Markers of disease severity at admission were the main predictors of inpatient mortality despite following WHO care guidelines, suggesting that current management strategies and resources may be insufficient for the sickest school-aged children. Surprisingly, epilepsy/convulsion appeared ‘protective’ compared to other reasons for admission in this hospitalised population, but would not be expected to be protective if compared to children in the community.

The 3.0% one-year post-discharge mortality, with almost three-quarters occurring within three months, broadly concurs with that observed in rural Mozambique three months after hospital-discharge (2.2%) among children 5 to 15 years old 14, but was much lower than one-year post-discharge mortality (16%) observed among children 5 to 12 years old in Tanzania 3. However, the Tanzanian study did not stratify results by age above or below 5 years and it seems likely that a higher prevalence of non-communicable diseases including cancer and heart disease reported in that population may have contributed to the higher risk of post-discharge death. However, the mortality rate of 31.2 deaths/1000 child-years observed was >34 fold higher than 0.91 deaths/1000 child-years within KHDSS among this age-group (unpublished data). The leading cause of death among the 26 children who died during readmission at KCH was malaria, similar to the leading cause assigned through verbal autopsies to children 1 to 4 years old who died in the community, but differing from that in infants among whom pneumonia was the leading causes of death in KHDSS 29

Tachypnoea, which may be associated with anaemia, hypoxia, sepsis or pneumonia, and weak pulse, a sign of circulatory insufficiency, were independently associated with post-discharge mortality which would suggest some children may be discharged with ongoing unstable vital signs that may lead to post-discharge deaths. Undernutrition was associated with post-discharge mortality, similar to most previous studies, which have identified nutritional status as a major risk-factor for post-discharge mortality in under-fives 3, 7, 14, 15, 17, 30. We previously showed that MUACZ is valuable in predicting post-discharge mortality among children >5 years in a model only adjusted for age, sex and HIV status 22.

We found severe anaemia was independently associated with post-discharge mortality; however, prior evidence of the effect of haemoglobin concentration on post-discharge mortality has been inconsistent, and may be influenced by the predominant causes of anaemia and local transfusion policies 3, 14, 16, 31– 34. Interestingly, we found no significant effect modification by anaemia on the effect of malaria on post-discharge mortality. The finding that children with malaria had lower post-discharge mortality than other reasons for admission is consistent with previous reports from this site among children <5 years of age where malaria parasitaemia had an apparently ‘protective’ effect on post-discharge mortality 11. This likely reflects the fact that when appropriately treated, mortality risk in children with malaria may be lower than in children with other causes of a similar apparent severity of illness.

In exploratory analyses, elevated creatine and hyperkalaemia, markers of impaired kidney function, were identified as predictors of both inpatient and post-discharge mortality. One study among children aged 2 to 12 years in Tanzania identified estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1·73m 2 as a predictor of one-year post-discharge mortality 3. This is an important finding since dehydration and sepsis are common and associated with acute kidney injury 35, and current guidelines recommend potentially nephrotoxic empiric gentamicin, without capacity for monitoring levels 36. However, clinical trials that could delineate attributable nephrotoxicity from background risks from renal disease, serious illness and dehydration have not yet been done.

Overall, our findings add to previous data in under-fives suggesting that hospitalisation marks an extended period of vulnerability, and reports suggesting that significant post-discharge mortality occurs outside hospital even among school-age children 7, 11, 17. The transition from inpatient to home care in the immediate three-month period following hospital discharge appears to be a critical period of risk. Risk stratification and targeted interventions for this population during this period might improve survival 4. However, current services, such as for the management of malnutrition in the community or those to manage anaemia, largely focus on children <5 years of age and may not operate in a way that fully addresses the mortality risk in this population 37, 38.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size, high rates of follow-up and the detailed longitudinal data available. However, this study also had some limitations. We used data from a single hospital, including only children resident within the nearby KHDSS, thus our results may not be generalizable to other sites or children living further away from the main road. Biochemical features were not systematically collected and could not be included in the primary analysis. We were not able to ascertain whether HIV infected children and malnourished children attended and complied with treatments from comprehensive care and nutrition clinics after discharge from hospital. We did not have access to causes of deaths among children who died at home or in other health facilities. Moreover, this study did not include data on caregiver or household characteristics, socio-economic situation or access to care.

Conclusion

This study highlights important differences in reasons for hospitalisation among school-aged children compared to younger children, and high rates of inpatient and post-discharge mortality among subgroups of school-aged children. To improve survival, active risk stratification and targeting intervention and follow-up in the early months after hospital discharge are needed, along with expansion of services that normally focus on the under-fives to vulnerable over-fives. The large proportion of deaths outside hospital suggests that facilitating access to healthcare among the most vulnerable, and priority clinical evaluation if unwell may be important measures.

Data availability

Underlying data

Harvard Dataverse: Replication Data for: Inpatient and post-discharge mortality among children 5-12 years old in rural Kenya. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZJOUWB 39.

The project contains the following underlying data:

Over5years_multipleadmissions.csv (contains clinical, anthropometric, CBC, blood & CSF culture at the time of hospital admission for children aged 5 to 12 years from 2007 to 2016, also provided in .dta format).

over5years_khdss.csv (contains vital status in the community following hospital discharge, also provided in .dta format).

over5yearschemistry.csv (contains the biochemistry variables that were not systematically collected at admission. This file is used to run a sub-analysis of the chemistry factors associated with both inpatient and post-discharge mortality, also provided in .dta format).

Data_Dictionary_NgariMM.pdf (contains a list of the variables of data collected at admission and discharge and their description).

Discharge_diagnosis codes.csv (contain the list of codes for discharge diagnosis).

Extended data

Harvard Dataverse: Replication Data for: Inpatient and post-discharge mortality among children 5-12 years old in rural Kenya. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZJOUWB 39.

This project contains the following extended data:

Additional data_Mngari et.al 2020.pdf (contains supplementary Tables S1−S5).

Data_Readme_NgariMM.txt (dataset description and usage instructions).

5older years analysis_v1.do (STATA script used to generate the summary participants characteristics at admission, reasons for admission to hospital and inpatient mortality including factors associated with inpatient deaths).

post-discharge analysis_over5years.do (STATA script that runs the post-discharge analysis. It merges the Over5years_multipleadmissions.dta with the over5years_khdss.dta, computes time under follow-up, post-discharge deaths, mortality rates and factors associated with post-discharge deaths).

Reporting guidelines

Harvard Dataverse: STROBE checklist for “Replication Data for: Inpatient and post-discharge mortality among children 5-12 years old in rural Kenya”. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZJOUWB 39.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0 )

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Kilifi County Hospital patients, staff at the paediatric wards, the laboratory and KHDSS for their contributions to this study. This manuscript is published with permission from the Director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust through core funding for the inpatient and community surveillance [098532, 092654, 084633 and 083579]. JAB, JW, MKM and MMN are supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as part of Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition (CHAIN) Network [OPP1131320]. JAB is currently funded by the MRC/DFID/Wellcome Trust Joint Global Health Trials scheme [MR/M007367/1]. MMN is currently supported by the WHO/TDR Clinical Research and Development Fellowships Program. MMN had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; peer review: 3 approved]

References

- 1. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME): Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2019, Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. 2019 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hill K, Zimmerman L, Jamison DT: Mortality risks in children aged 5-14 years in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic empirical analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(10):e609–16. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00044-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hau DK, Chami N, Duncan A, et al. : Post-hospital mortality in children aged 2-12 years in Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202334. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masquelier B, Hug L, Sharrow D, et al. : Global, regional, and national mortality trends in older children and young adolescents (5-14 years) from 1990 to 2016: an analysis of empirical data. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1087–e1099. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30353-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osano BO, Were F, Mathews S: Mortality among 5-17 year old children in Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:121. 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.121.10727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morris SK, Bassani DG, Awasthi S, et al. : Diarrhea, pneumonia, and infectious disease mortality in children aged 5 to 14 years in India. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20119. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nemetchek B, English L, Kissoon N, et al. : Paediatric postdischarge mortality in developing countries: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e023445. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiens MO, Pawluk S, Kissoon N, et al. : Pediatric Post-Discharge Mortality in Resource Poor Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66698. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J, et al. : Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(5):1276–83. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cc1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stanton B, Clemens J, Khair T, et al. : Follow-up of children discharged from hospital after treatment for diarrhoea in urban Bangladesh. Trop Geogr Med. 1986;38(2):113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moïsi J, Gatakaa H, Berkley J, et al. : Excess child mortality after discharge from hospital in Kilifi, Kenya: a retrospective cohort analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(10):725–32, 732A. 10.2471/BLT.11.089235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Opoka RO, Hamre KES, Brand N, et al. : High postdischarge morbidity in Ugandan children with severe malarial anemia or cerebral malaria. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6(3):e41–e48. 10.1093/jpids/piw060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olupot-Olupot P, Engoru C, Thompson J, et al. : Phase II trial of standard versus increased transfusion volume in Ugandan children with acute severe anemia. BMC Med. 2014;12:67. 10.1186/1741-7015-12-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Madrid L, Casellas A, Sacoor C, et al. : Postdischarge mortality prediction in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20180606. 10.1542/peds.2018-0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Talbert A, Ngari M, Bauni E, et al. : Mortality after inpatient treatment for diarrhea in children: A cohort study. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):20. 10.1186/s12916-019-1258-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chami N, Hau DK, Masoza TS, et al. : Very severe anemia and one year mortality outcome after hospitalization in Tanzanian children: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0214563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ngari MM, Fegan G, Mwangome MK, et al. : Mortality after Inpatient Treatment for Severe Pneumonia in Children: a Cohort Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2017;31(3):233–242. 10.1111/ppe.12348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. English M, Ngama M, Musumba C, et al. : Causes and outcome of young infant admissions to a Kenyan district hospital. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(5):438–43. 10.1136/adc.88.5.438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scott JAG, Bauni E, Moisi JC, et al. : Profile: The Kilifi health and demographic surveillance system (KHDSS). Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):650–7. 10.1093/ije/dys062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berkley JA, Lowe BS, Mwangi I, et al. : Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(1):39–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa040275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organisation, WHO: Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva, Switz World Heal Organ. 2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mramba L, Ngari M, Mwangome M, et al. : A growth reference for mid upper arm circumference for age among school age children and adolescents, and validation for mortality: Growth curve construction and longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3423. 10.1136/bmj.j3423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, et al. : Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;58(9):660–7. 10.2471/blt.07.043497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mwangome MK, Fegan G, Prentice AM, et al. : Are diagnostic criteria for acute malnutrition affected by hydration status in hospitalized children? A repeated measures study. Nutr J. 2011;10:92. 10.1186/1475-2891-10-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Borsboom GJJM, et al. : Internal validation of predictive models: Efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):774–81. 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00341-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gathara D, Malla L, Ayieko P, et al. : Variation in and risk factors for paediatric inpatient all-cause mortality in a low income setting: Data from an emerging clinical information network. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):99. 10.1186/s12887-017-0850-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ayieko P, Ogero M, Makone B, et al. : Characteristics of admissions and variations in the use of basic investigations, treatments and outcomes in Kenyan hospitals within a new Clinical Information Network. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(3):223–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chopra M, Stirling S, Wilkinson D, et al. : Paediatric admissions to a rural South African hospital: Value of hospital data in helping to define intervention priorities and allocate district resources. S Afr Med J. 1998;88(6 Suppl):785–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ndila C, Bauni E, Mochamah G, et al. : Causes of death among persons of all ages within the kilifi health and demographic surveillance system, Kenya, determined from verbal autopsies interpreted using the InterVA-4 model. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25593. 10.3402/gha.v7.25593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chhibber AV, Hill PC, Jafali J, et al. : Child mortality after discharge from a health facility following suspected pneumonia, meningitis or septicaemia in rural Gambia: A cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137095. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scott SP, Chen-Edinboro LP, Caulfield LE, et al. : The impact of anemia on child mortality: An updated review. Nutrients. 2014;6(12):5915–32. 10.3390/nu6125915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maitland K, Kiguli S, Olupot-Olupot P, et al. : Immediate transfusion in African children with uncomplicated severe anemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):407–419. 10.1056/NEJMoa1900105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maitland K, Olupot-Olupot P, Kiguli S, et al. : Transfusion volume for children with severe anemia in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):420–431. 10.1056/NEJMoa1900100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brabin BJ, Premji Z, Verhoeff F: An analysis of anemia and child mortality. J Nutr. 2001;131(2S-2):636S–645Sdiscussion 646S–648S. 10.1093/jn/131.2.636s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chami N, Kabyemera R, Masoza T, et al. : Prevalence and factors associated with renal dysfunction in children admitted to two hospitals in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):79. 10.1186/s12882-019-1254-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McWilliam SJ, Antoine DJ, Smyth RL, et al. : Aminoglycoside-induced nephrotoxicity in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(11):2015–2025. 10.1007/s00467-016-3533-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Berkley JA, Ngari M, Thitiri J, et al. : Daily co-trimoxazole prophylaxis to prevent mortality in children with complicated severe acute malnutrition: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(7):e464–73. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maitland K, Olupot-Olupot P, Kiguli S, et al. : Co-trimoxazole or multivitamin multimineral supplement for post-discharge outcomes after severe anaemia in African children: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1435–e1447. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30345-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ngari MM, Murunga S, Otiende M, et al. : Replication Data for: Inpatient and post-discharge mortality among children 5-12 years old in rural Kenya.Harvard Dataverse, V1.2020. 10.7910/DVN/ZJOUWB [DOI]