The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is now a worldwide concern. Clinicians are being forced to consider COVID-19 as a part of differential diagnoses under these circumstances. Here, we report a case of lung adenocarcinoma in an elderly female patient receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, whose radiological findings were thought to mimic those of the novel COVID-19 pneumonia.

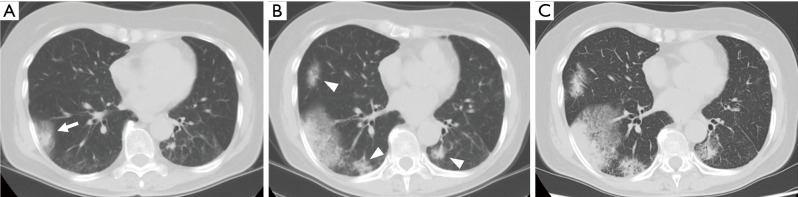

A 71-year-old female patient was started on nivolumab as a second-line treatment for stage IVA metastatic lung adenocarcinoma after undergoing 8 months of first-line chemotherapy (carboplatin plus pemetrexed, followed by pemetrexed maintenance). During the first-line treatment, an initial partial response to first-line treatment was followed by disease progression with the primary tumor in the left lower lobe. She exhibited transient pseudoprogression after 3 cycles of nivolumab with a subsequent, remarkable near-complete response and could successfully continue the treatment without adverse effects. However, 30 months after the initiation of nivolumab, chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed ground-glass opacity with consolidation in the right lower lobe (Figure 1A). Nivolumab treatment was discontinued at this time. A CT-guided lung biopsy revealed an adenocarcinoma that was positive for thyroid transcription factor-1 (at this point, it was before the COVID-19 pandemic). Although third-line chemotherapy with docetaxel plus ramucirumab was subsequently initiated, the chest radiograph revealed that the metastatic lung tumors in the right lower lobe gradually enlarged. Three months after the initiation of third-line chemotherapy, she developed acute dry cough. Chest CT scans showed newly developed bilateral multiple ground-glass opacities with consolidations predominantly present in the peripheral lung in addition to the known growing metastatic lung tumors in the right lower lobe (Figure 1B). Because her symptoms and chest shadows progressed relatively rapidly, and this occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a high possibility of COVID-19 pneumonia in addition to tumor progression. Therefore, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2 using a nasopharyngeal swab was performed, which, however, yielded a negative result. Based on the subsequent clinical course, including elevated serum tumor markers, she was ultimately diagnosed with tumor progression. Finally, the best supportive care was selected based on her general condition due to tumor progression (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the lung. (A) CT scan showing ground-glass opacity with consolidation in the right lower lobe (arrow). (B) CT scan showing newly developed bilateral multiple ground-glass opacities with consolidations predominantly present in the peripheral lesion (arrowheads). (C) CT scan showing tumor progression at 6 weeks after the second CT scanning.

Cancer patients are at a higher risk of infection from SARS-CoV-2 and severe illness or death from COVID-19 as compared to patients without cancer (1). Abnormal chest shadows seen in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors are often difficult to diagnose because of various possible causes, such as immune-related pneumonitis, tumor progression, and tumor pseudoprogression (2). During this pandemic, clinicians must be vigilant about identifying potential differential diagnoses of COVID-19. The CT findings in our case showed bilateral ground-glass opacities with consolidations predominantly present in the peripheral lower lobes, which are consistent with the characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia (3). CT findings of COVID-19 pneumonia can also overlap with those of treatment-related pneumonitis, which is seen in immunotherapy and molecular-targeted therapy (4,5).

At present, it is impossible to exclude COVID-19 pneumonia based on the radiological findings; complete exclusion is difficult even when the RT-PCR result is negative, due to its low sensitivity. Patients with lung cancer are especially likely to have respiratory symptoms and abnormal lung shadows at the start of chemotherapy. Therefore, clinicians should be aware that such patients are at a higher risk of contracting severe COVID-19 in spite of the difficulty in diagnosing it. Our findings highlight the acute need for a practical and accurate COVID-19 screening model for cancer patients during the pandemic.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a free submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-2393). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:335-7. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masuhiro K, Shiroyama T, Nagatomo I, et al. Unique Case of Pseudoprogression Manifesting as Lung Cavitation After Pembrolizumab Treatment. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:e108-9. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zu ZY, Jiang MD, Xu PP, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Perspective from China. Radiology 2020;296:E15-25. 10.1148/radiol.2020200490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabrò L, Peters S, Soria JC, et al. Challenges in lung cancer therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:542-4. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30170-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang HL, Chen YH, Taiwan HC, et al. EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:e129-31. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as