Abstract

Introduction

Acetabular fractures in the elderly population are particularly challenging for orthopedic fracture surgeons to treat. Anterior column posterior hemitransverse (ACH) and both column (BC) fractures account for over 70% of these injuries in geriatric patients. Nonoperative management of these injuries has a mortality of about 79% and patients generally have a minimal chance of return to independent living. The aim of our study was to identify the degree of protrusio deformity geriatric patients with these injuries present with and if indirect reduction through a Stoppa approach was sufficient to improve protrusio deformity.

Methods

Patients older than 60 years of age who had ACH and BC pattern acetabular fractures treated at the BIDMC in Boston, MA between 2015 and 2020 were included in this study. Pelvic AP and Judet views were reviewed at injury and each available post-operative follow up. We modified the femoral head extrusion index and used its inverse to measure the level of protrusio at each time point (-FHEI). Patient outcomes were also graded as excellent, good, fair and poor based on post-operative follow up.

Results

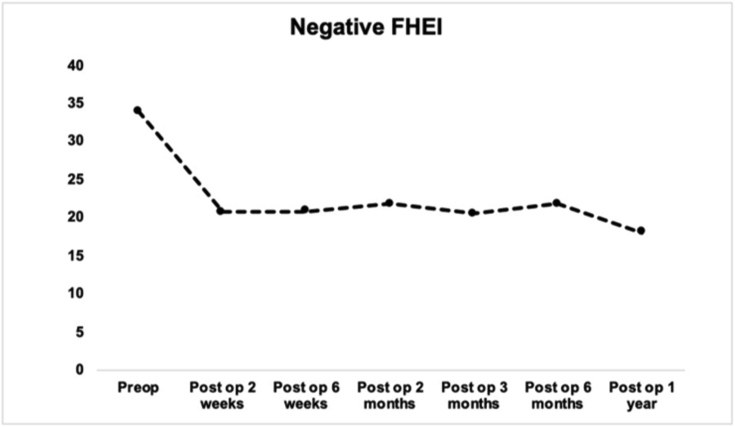

Sixteen patients were included based on above criteria and average -FHEI at injury was 34.85% and decreased significantly to an average of 21.5% postoperatively and remained stable at all follow up points. At one year follow up (n = 2), the mean -FHEI was 18.15%. Most patients had good (4) or excellent (9) outcomes.

Conclusions

We present short term results of indirect reduction of ACH and BC acetabular fractures in geriatric patients using a PRO quadrilateral surface plate, which was largely successful in controlling the primary protrusio deformity seen in these patients. This allowed for restoration of the anterior column, with limited surgical morbidity through a relatively simple and straightforward surgical approach.

Keywords: Trauma, Protrusio, Acetabular fracture, Geriatric trauma

1. Introduction

Acetabular fractures in the elderly population are particularly challenging for orthopedic fracture surgeons to treat. While these are unusual relative to other fractures associated with age and osteoporosis, the mortality in patients over 65 with acetabular fractures is reported to be as high as 33%.1, 2, 3 As is the case with many skeletal injuries, acetabular fractures generally present in bimodal distribution, with an initial peak of injury prevalence among young patients suffering high energy injuries, and a second peak occurring in patients over 65 suffering low energy falls, generally from standing. In the elderly, the presence of osteoporosis can contribute to the dramatic displacement often seen in these patients. Similarly, the fracture patterns also vary between these two general groups. In younger patients, posterior wall injuries, with and without posterior column involvement, tend to predominate in most series.2 In direct contrast to this, the elderly population tends to consist largely of anterior column posterior hemitransverse (ACH) and both column (BC) injuries.3 In one recent series these two closely related patterns accounted for over 70% of geriatric acetabular fractures on presentation.1 Lastly, the nonoperative care of these patients is often singularly unsatisfying. Protrusio deformities in the elderly only worsen with time, and patients treated with traction alone have one-year mortality rates comparable to non-operatively managed hip fractures was 79%.1 Patients are often unable to return to independent living, and many require full time nursing care. Conversion to total hip replacement in the presence of significant protrusio is also challenging, with particularly high surgical morbidity in patients who eventually develop pelvic discontinuity.4

To address these challenges, a range of injury specific plates have been commercially available for several years. These anterior column plates have been designed specifically to address the protrusio deformity seen in the elderly.5 The purpose of this paper was to examine how effective an anterior approach with application of a PRO quadrilateral surface plate was in controlling this deformity. We sought to answer three questions: (1) How much deformity did elderly patients present with? (2) Was an indirect reduction through a Stoppa approach, with or without addition of the ilioinguinal top window, sufficient to improve the protrusio deformity and (3) Would the deformity simply recur in short term follow up?

2. Methods

Patients who had ACH and BC pattern acetabular fractures treated at the BIDMC in Boston, MA between 2015 and 2020 were included in this study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria for patient selection were all-comers of age greater than 60, use of the Stoppa approach with indirect reduction, use of the PRO quadrilateral surface plate and had a minimum follow up of 2 months postoperatively. Patients were not excluded based on comorbidities or polytrauma at the time of injury.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Mean Age | 74 | |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 3 | |

| Osteoporosis | 2 | |

| Anticoagulation | 3 | |

| Smoker | 3 | |

| Sex | Male | Female |

| 9 | 7 | |

| Laterality | Right | Left |

| 10 | 6 | |

2.1. Surgical technique

In all patients presented in this series, a limited surgical strategy was discussed with the patients and implemented in their care, to primarily address only the protrusio deformity. The reduction was limited entirely to what could be achieved indirectly. While we recognized that this would likely result in a high rate of post traumatic arthritis, we posit that addressing the primary protrusio deformity facilitates delayed total hip arthroplasty in those patients whose activity level justified a secondary procedure after the acetabular fracture had healed.

All of the patients in the series received a Stoppa approach, and in selected cases where access to the superior portion of the plate was needed, the top window of the ilioinguinal approach was added as a second incision. Our standard approach included a generous phannenstiel incision. The midline raphe between the rectus muscles was developed and carried down to the symphysis pubis. The respective rectus muscle was then elevated off the symphysis, giving access to the retropubic space of Retzius and the superior aspect of the pubic rami. Mobilization was then undertaken of the soft tissues superiorly along the pubic rami, carrying the dissection into the true pelvis and accessing the quadrilateral plate.

At this point, a 5 mm half pin was placed through the trochanter and into the femoral neck to provide lateral traction and reduce the hip. Once the head was reduced back under the dome, direct reduction of the quadrilateral plate and any displacement of the anterior column seen along the pelvic brim can be performed. If the primary displacement was anterior and the reduction proved difficult from the Stoppa approach alone, the superior window of the ilioinguinal approach was used. Through this window, a ball spike pusher was applied to the brim, and again seen directly through the Stoppa window.

Once the protrusio was addressed, the PRO quadrilateral surface plate was applied (Stryker, Switzerland). The plate itself generally acted as a buttress for the anterior column and did not require additional screw fixation into the quadrilateral plate to control the protrusio. Once the plate was applied and secured, lateral traction was released, and the ability of the construct to hold the head away from the deformity was assessed. Standard closure was then accomplished, with attention paid to repairing the rectus insertion as necessary.

All patients were posited to undergo standard post-operative rehabilitation protocol at our institution with immediate touchdown weightbearing for standing/pivoting and eventual transition to partial weightbearing at 1 month and progression to full weightbearing as tolerated within 3 months postoperatively unless they were limited by pain or prior level of activity. The patients were seen by physical therapy in the hospital and followed up either outpatient or seen at home depending on their level of activity.

2.2. Outcomes

Plain films of the pelvis with Judet views at the time of injury and each subsequent follow up appointment were reviewed. Progress notes from surgeons at the time of each follow up were reviewed and an assessment of poor to excellent was made by the primary surgeon based on patient’s pain level, return of function and maintenance of reduction. We modified the femoral head extrusion index (FHEI) described by Linnea et al. as the percentage of the femoral head not covered by the acetabulum (calculated as the femoral head lateral to the extent of the acetabulum divided by the total width of the femoral head and multiplying by hundred) to measure negative FHEI (-FHEI) calculated as the distance from the lateral edge of the acetabulum to the lateral edge of the femoral head divided by the total width of the femoral head multiplied by hundred (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).5 This was measured on the injury and follow up plain films (see Fig. 3).

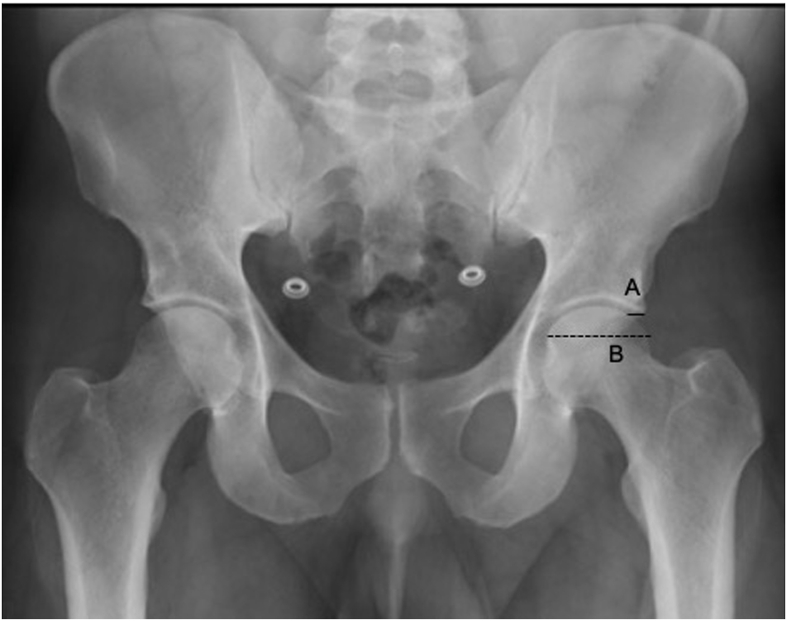

Fig. 1.

On this anterior-posterior view of the pelvis, A represents the distance between the lateral aspect of the acetabulum and the femoral head and B represents the total width of the femoral head. The -FHEI is A/B multiplied by 100 to represent the percentage of the femoral head displaced medially.

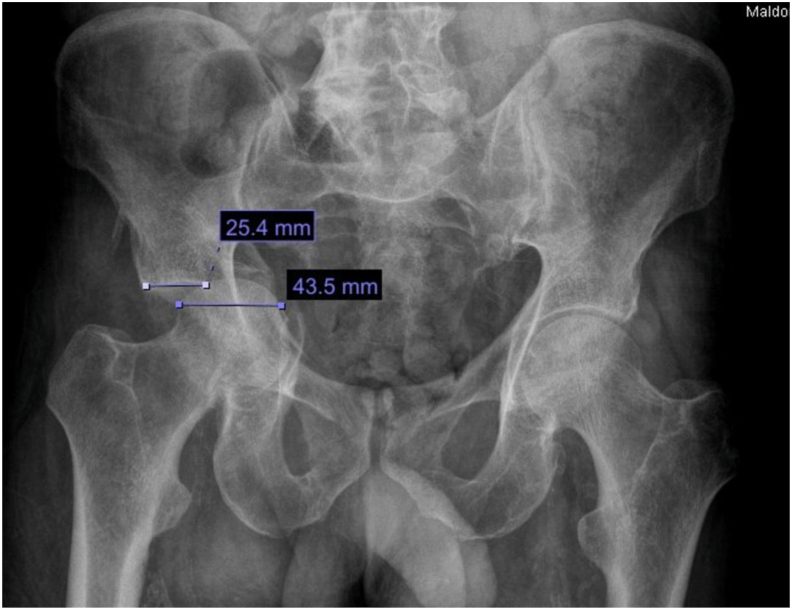

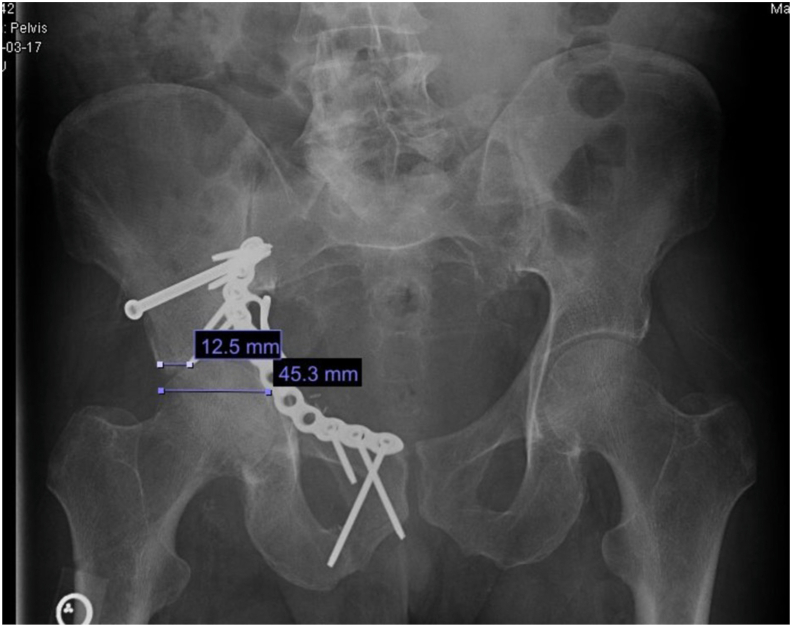

Fig. 2.

(a) Example of -FHEI at the time of injury. The distance between the lateral aspect of the acetabulum and the femoral head is 25.4 mm and the width of the femoral head is 43.5 mm, making the protrusio deformity 58.4%. (b) Example of -FHEI postoperatively at 2 weeks. The distance between the lateral aspect of the acetabulum and the femoral head is 12.5 mm and the width of the femoral head is 45.3 mm, making the protrusio deformity 27.6%.

Fig. 3.

Change in -FHEI from injury to postoperatively and at each available follow up point.

3. Results

A total of 16 patients were included in the study based on aforementioned inclusion criteria, nine of whom were men and seven were women (Table 1). Two patients had associated both column and 14 patients had anterior column posterior hemitransverse acetabular fractures. One patient had a total hip arthroplasty at the time of ORIF, making -FHEI calculations unavailable. Another patient had a DHS in place at the time of injury and severe arthritis that prevented -FHEI calculation. The mean length of follow up was five months.

The average -FHEI at injury was 34.85%, meaning one third of the femoral head was medial to the lateral aspect of the acetabulum. It decreased significantly to an average of 21.5% postoperatively and remained stable at all follow up points. At one year follow up (n = 2), the mean -FHEI was 18.15% (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Average -FHEI at the time of injury and postoperatively at each available follow up.

| Mean-FHEI (n) | |

|---|---|

| Injury | 34.85 (14) |

| 2 weeks post-op | 21.5 (14) |

| 6 weeks post-op | 21.3 (14) |

| 2 months post-op | 21.9 (4) |

| 3 months post-op | 21.4 (10) |

| 6 months post-op | 21.9 (6) |

| 1 year post-op | 18.15 (2) |

Based on surgeon assessment of range of motion, function, pain and need for further intervention at the final available follow up, nine patients had excellent results, four had good, one had fair and two had poor results. One patient had concurrent total hip arthroplasty at the time of fracture fixation complicated by a periprosthetic femur fracture treated with a revision total hip arthroplasty and further by prosthetic joint infection treated with irrigation and debridement, and liner exchange. One patient had a well-healed fracture at final follow up but postoperative course complicated by foot drop that did not resolve at one year after surgery. One patient has had persistent postoperative pain and has a total hip arthroplasty planned.

4. Discussion

Acetabular fractures are challenging to treat, and experience across many centers shows that even small amounts of incongruity can lead to early failure and require conversion to total hip replacement. Furthermore, total hip replacements in general provide excellent hip function.6 In this series, we sought to balance the challenges of obtaining an absolutely congruent joint with the need to address the protrusio deformity prior to obtaining a total hip arthroplasty. We recognized that in many of these ACH and BC patterns, these patients also presented with significant dome impaction, and that accessing this impaction in this age group requires significant additional surgical morbidity.

Rather than attempting to obtain an absolutely congruent reduction, we sought to address the major deforming forces and correct the protrusio deformity through a relatively safe and low morbidity Stoppa approach. While the majority of the protrusio can be readily corrected through this approach, holding the reduction can be challenging. We commonly used specifically designed PRO quadrilateral surface plates (Stryker, Inc) to hold the reduction, and this series looks at the ability of these deformity specific plates to hold the reduction we were able to achieve in the immediate postoperative period.

In general, patients had a significant deformity at the time of injury, with an average of 34.85% -FHEI, which improved significantly postoperatively, and the reduction was maintained at each follow up. Most patient had good to excellent results postoperatively considering their range of motion, pain and functional level.

Our approach is somewhat controversial in that little attempt was made at securing an absolutely anatomic reduction. This was intentional on our part, in that frail elderly patients are at particular risk for the morbidity associated with surgical complications, and we chose to apply a straightforward surgical approach with generally quite low complication rates in this particular population.1 Post traumatic arthritis is often well tolerated in low demand patients, and for those who are high enough demand to have significant pain, a secondary total hip can be accomplished once the continuity of the anterior column has been restored. This also raises the question of whether a primary total hip should be done immediately to hasten the patient’s recovery. However, the same argument for limited morbidity applies, and we have generally chosen a conservative approach, recognizing that two separate and delayed surgeries may be safer for elderly patients than the cumulative risk associated with two immediate procedures.

Lastly, we had available to us anatomically designed PRO quadrilateral surface plates, but a similar approach could easily be employed using two contoured pelvic reconstruction plates. Prior to the advent of these plates, successful series were reported using a similar strategy, with recon plates applied inside the true pelvis along the quadrilateral plate through a Stoppa approach, and secondary plates as needed applied along the anterior column through the top window of the ilioinguinal approach.4,7, 8, 9

5. Conclusions

In summary, we present short term results of a PRO quadrilateral surface plate which was largely successful in controlling the primary deformation seen in elderly ACH and BC fractures. This allowed for visualization and reduction of the anterior column and indirect joint reduction, with limited surgical morbidity through a relatively simple and straightforward surgical approach. While some incongruity and medialization did occur even in the immediate postoperative period, in no instance did the deformity worsen or the anterior column displaces further, which portends well for conversion to total hip should that be necessary.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Sravya T. Challa, Email: schalla@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Paul Appleton, Email: pappleto@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Edward K. Rodriguez, Email: ekrodrig@bidmc.harvard.edu.

John Wixted, Email: jwixted@bidmc.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Firoozabadi R., Cross W.W., Krieg J.C., Routt M.L.C. Acetabular fractures in the senior population- epidemiology, mortality and treatments. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2017;5(2):96–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letournel É., Judet R. second ed. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg, Germany: 1993. Fractures of the Acetabulum. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson T.A., Patel R., Matta J.M. 2008. 24th Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association. Denver, CO. Fractures of the acetabulum in patients over 60 years of age: epidemiology, fracture patterns and radiographic morphology. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archdeacon M.T., Kazemi N., Collinge C., Budde B., Schnell S. Treatment of protrusio fractures of the acetabulum in patients 70 years and older. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(5):256–261. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318269126f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linnea W.K., Jesse M.K., Kraeutler M.J., Garabekyan T., Mei-Dan O. The anteroposterior pelvic radiograph. JBJS. 2018;100(1):76–85. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ries M.D. Total hip arthroplasty in acetabular protrusio. Orthopedics. 2009;32(9) doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090728-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egli R.J., Keel M.J.B., Cullmann J.L., Bastian J.D. Secure screw placement in management of acetabular fractures using the suprapectineal quadrilateral buttress plate. BioMed Res Int. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/8231301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qureshi A.A., Archdeacon M.T., Jenkins M.A., Infante A., DiPasquale T., Bolhofner B.R. Infrapectineal plating for acetabular fractures: a technical adjunct to internal fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(3):175–178. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culemann U., Holstein J.H., Köhler D. Different stabilisation techniques for typical acetabular fractures in the elderly--a biomechanical assessment. Injury. 2010;41(4):405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]