Abstract

Management of acetabular fractures in elderly patients is challenging. The challenges arise due to associated medical comorbidities, poor bone quality and comminution. There are multiple modalities of treatment. the exact algorithms or treatment remain undefined. Treatment is still based on experience and some available evidence. The options include conservative treatment, percutaneous fixation, open reduction internal fixation and the acute fix and replace procedure. There is a well recognised risk of each treatment option. We present a narrative review of the relevant available evidence and our treatment principles based on experience from a regional tertiary pelvic-acetabular fracture service.

Keywords: Acetabulum fractures, Elderly, Geriatric, Percutaneous, Fix and replace, Combined hip procedure, Conservative

1. Introduction

Demographically, the geriatric population across the world has seen a steady increase which is associated with an increasing incidence of geriatric pelvic and acetabular fractures in osteoporotic bone.

The age range which defines the elderly population has varied from 55 to 65 years. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 28, 29 Ferguson et al. reported a 2.4 fold increase in the incidence of fractures in >60 years of age between early (1980–1993) and late period of study (1994–2007).

The annual incidence of acetabular fractures is estimated at 2000 per year in the United Kingdom with 72.5% of these occurring in older patients (patients greater than 65 years of age) 38 These fractures also lead to a major impact on walking ability and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to complications associated with bedrest and concomitant medical conditions. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

These fractures are commonly low energy injuries and usually occur after falls from standing height although high energy injuries are also seen from traffic collisions or accidents involving pedestrians.2, a)

This brief review attempts to summarise the available evidence behind each treatment philosophy to try to identify a logical rationale for treatment recommendations, which is also based on experience obtained in regional tertiary pelvic-acetabular fracture and arthroplasty services.

1.1. Fracture characteristics and bone quality

This mechanism of injury results in fairly typical fracture patterns 2,5 involving the anterior column, quadrilateral plate, medial protrusion of femoral head and varying degrees of supero-medial or anteromedial dome impaction. Older patients 2, 5 have shown a preponderance of fractures involving the anterior column, anterior column with posterior hemi transverse, and associated both column injuries. 8,9

1.2. Principles and goals of treatment

The goals of treatment in this population do not differ from those of their younger counterparts and should include pain relief, rapid mobilisation, and where possible an attempt to return to independent activities of daily living. 3,5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Complicating factors include medical co-morbidities, degenerative joint disease and poor bone quality with fracture comminution. 2,6,7,8 These factors also predict poorer outcomes.

The other difficulty is the unreliable surgical fixation obtained after open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) in poor bone quality which has a reported high failure rate and conversion to secondary THA. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 There may also be rapid onset of posttraumatic arthritis despite ORIF. 5,6,8 20–25% of acetabular fractures in the elderly following ORIF needed revision and conversion to delayed THR within the first 1–2 years.

2. Treatment philosophies

2.1. The treatment options available include the following 3,5,8, 9, 10,12

-

(i)

Conservative management

-

(ii)

Percutaneous fixation in situ/(or after closed or open reduction)

-

(iii)

Open reduction with internal fixation

-

(iv)

The combined hip procedure-acute fix and replace (this consists of performing osteosynthesis of the fracture to achieve sufficient stability to allow the simultaneous implantation of a total hip arthroplasty (THA).

-

(v)

Acute THR without osteosynthesis – where the acetabular component alone with screws will also provide sufficient stabilisation of the fracture also – usually undisplaced or incomplete fractures.

-

(vi)

Delayed THA after healing of the fracture

Each treatment option has the potential for satisfactory results in properly selected patients or can be associated with risks and complications.

Regrettably there is no clear consensus regarding the best treatment option or indications. There is also a paucity of high quality randomised trials comparing these treatment options.

3. Conservative management

3.1. Rationale

Traditionally acetabular injuries in the elderly population have been treated conservatively with varying results. Letournel described the classical “secondary congruence” of some types of acetabular fractures (associated both column) with good long term outcomes. 17,20

Potential disadvantages of traditional conservative management include the risks of prolonged recumbency in frail elderly patients (pressure sores, urinary tract infections, chest infections, muscle wasting and difficulty in returning to good levels of mobility) 25 especially with long periods of skeletal traction. Prolonged bed rest using skeletal traction has probably got very little place in modern management of these fractures.

There is a recent trend leaning towards surgical management but there is scarcity of high quality outcomes data to show that mortality, morbidity or functional results are necessarily better following surgery.

The increasing trend towards surgery has to be carefully balanced against the risks of anaesthesia and surgical complications in frail, elderly medically compromised patients, including blood loss, neurovascular injury, infection, failed fixation and failure to achieve satisfactory reduction in comminuted osteoporotic fractures. 10,12,13,15,16 A second often more complicated salvage operation may be needed if the surgery fails.

Combined geriatrician and orthopaedic management of elderly patients with fractures, in a multi-disciplinary setting allows for medical optimisation, safer and earlier surgery, fewer post-operative complications, and shorter length of stay.

3.2. Indications

Indications for conservative management identified in the literature and from experience have included certain patient or fracture characteristics.

I. Patient factors – physiologically compromised and medically unfit patients (cardiac, respiratory, neurological, haematological, or multi-system disease who would not tolerate extensive surgery due to significant comorbidities), advanced dementia, or severely limited pre-injury mobility.

II. Fracture personality-undisplaced or minimally displaced or stable fractures (anterior column or wall), fractures that exhibit secondary congruency of the joint, (such as associated both column), highly comminuted fractures where reliable fixation cannot be obtained in osteoporotic bone without accepting a high risk of failure and secondary surgery.

III. Surgical factors-lack of availability of sufficient multi-disciplinary experience to offer reliable complex reconstructive surgery and provide safe care for this complex group of patients.

Significant instability (a subluxed or dislocated joint where the femoral head does not fall underneath the dome) and/or major incongruity may be poorly tolerated by the hip joint. These may represent contraindications to conservative management although that is not necessarily the conclusion by default. 3,6,10,12,16,22 Tornetta 17 has outlined the criteria for non-operative management of acetabular to help guide decision making in the elderly.

3.3. Methods

Skeletal traction for long periods should have little role in managing these fractures, although it may be required in rare circumstances. 10,12,16 Capsular ligamentotaxis is deemed to be insufficient in achieving and maintaining reduction. Also it is difficult to maintain safe skeletal traction in porotic bone due to the risk of pin disengagement and pull-out.

There has to be a balance between the need for immobility to prevent fracture displacement (for which traction has traditionally been employed) versus early functional treatment focussed on treating the patient rather than the precise radiological appearance of the fracture acknowledging a small but possible risk of fracture displacement. 18

Good “functional” conservative treatment should include a multi-disciplinary team 14 approach including specialist physiotherapists, good nursing care, pain management teams, occupational therapists, care of the elderly physicians, nutritionists, and community rehabilitation and support teams.

Meticulous attention should be paid to achieving excellent pain management (just like that afforded to patients who undergo surgery – (O’Toole et al.), correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance, good pressure area care, early chest and limb physiotherapy, early progression to a seated position, VTE (venous thromboembolism) prophylaxis (with appropriate risk assessment), and early ambulation as pain allows. Good orthogeriatric support from internists is vital for medical optimisation. 14

Early mobilisation is the cornerstone of successful treatment and should focus on safe supervised ambulation regimes under the guidance of experienced physiotherapists in the hospital and in the community. Non displaced acetabular fractures in elderly can be appropriately treated non operatively by early mobilisation with physiotherapy and weight bearing as tolerated within the limits of pain.

We find that elderly patients can rarely comply with or can cope with advice to ambulate non-weight bearing due to medical problems, upper limb weakness, affection of other joints, issues with balance and coordination or problems with vision. These patients are at high risks of further falls and additional harm. We find that patients largely self-regulate their weight bearing based on pain relief and ability. We have therefore followed early supervised weight bearing as pain allows with the appropriate walking aids.

There is the concern about fracture displacement with this approach. It is therefore important to maintain a good clinical and radiologic surveillance for late displacement.

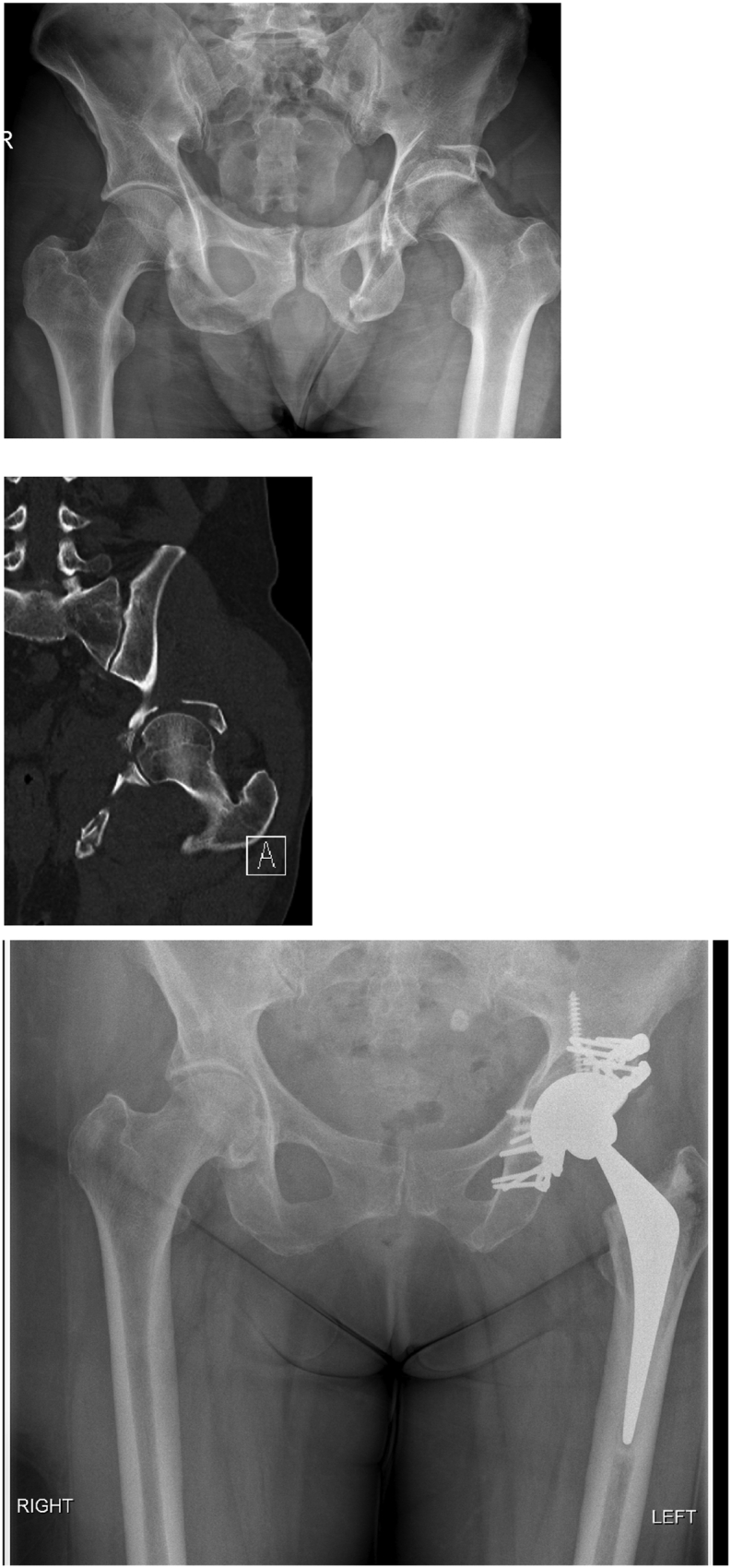

Interestingly, after the process of healing, it is commonly observed that varying levels of acetabular displacement and secondary arthritis (Fig. 1) following conservative treatment is often clinically well-tolerated for a number of years. Fig. 2, Fig. 3 This is also borne out in literature. 18

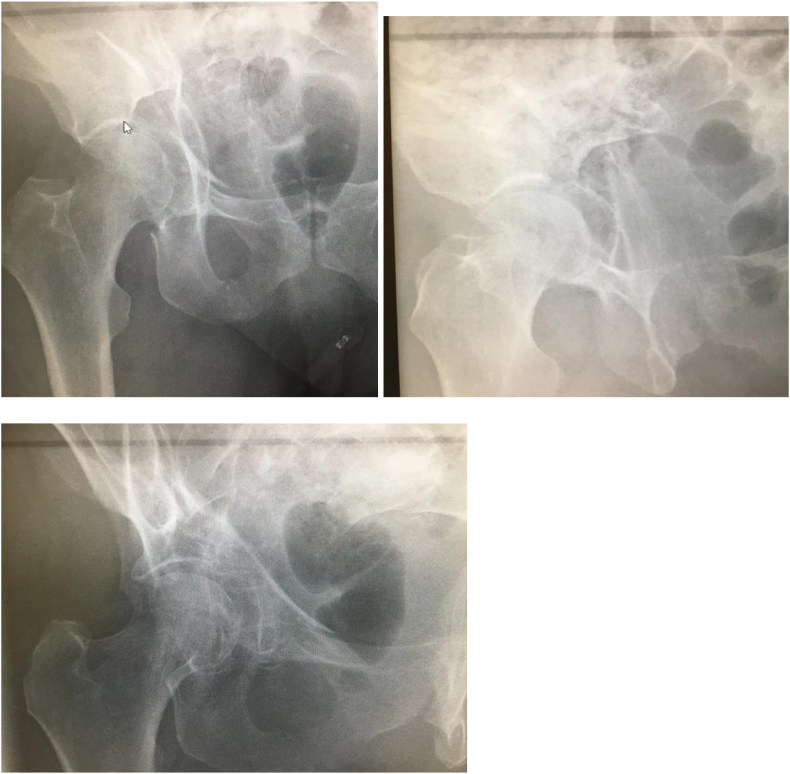

Fig. 1.

a, b, c- 78 years, female patient, comminuted right acetabulum fracture with significant displacement, degenerative spinal scoliosis, independently mobile before fracture.

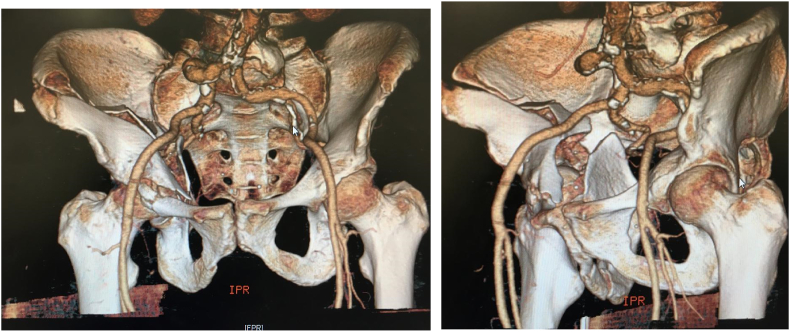

Fig. 2.

a, b- 3 D CT scans of the injury.

Fig. 3.

a,b - outcome at 3 years after conservative treatment, residual incongruity, persistent displacement, areas of malunion and non-union, despite which there was no hip pain, walks unrestricted, and swims twice a week.

3.4. Outcomes and evidence

Outcomes comparing different treatment philosophies (ORIF v/s Acute fix and replace v/s conservative treatment) for displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly are scarce, inconsistent and often conflicting.

A multicentre study by Ryan et al. (retrospective case series) showed that elderly patients with acetabular fracture patterns that would have otherwise qualified for operative fixation in younger patients demonstrated surprisingly good outcome scores when treated nonoperatively. 18 Our experience has been consistent with these authors and other studies. 61,63

There is no convincing evidence that conservative management leads to a higher mortality or a higher re-operation rate. A retrospectively analysis of 176 patients with mean 24 months follow-up for mortality, complications and long-term functional outcome in elderly patients with fragility fractures of the acetabulum 15 found that mortality and in-hospital complications are high among geriatric patients with low-energy fractures of the acetabulum even when treated operatively. 61,63

Secondary conversion rates to THA are similar to those seen in younger patients. Functional results at final follow-up between operatively and non-operatively treated patients were without difference.

Magu NK et al. retrospectively analysed 69 patients with 71 displaced acetabular managed conservatively showing that non-operative treatment of displaced acetabular fractures can give good radiological and functional outcome in patients with congruent reduction. 19

Being a regional arthroplasty unit comes with the advantage of a reasonably captive follow-up population. A small proportion of these cases go on to needing a late THA. Technically, we have found it fairly straightforward to perform a delayed primary arthroplasty of the conservatively treated acetabular fracture (even after malunion or some areas of nonunion) using a mix of traditional (cemented acetabular sockets with impaction bone grafting) and contemporary (ultra-porous acetabular components with screws) arthroplasty techniques.

Good results of conservative management were reported by Magala et al. 62 even with residual displacement of acetabular fractures treated conservatively.

In contrast, performing a delayed THA in a previously surgically treated acetabulum is often technically more difficult with surgical scarring, presence of metalwork, scarred or adherent sciatic nerve, bleeding risks, and a higher risk of peri-operative complications such as infection or heterotopic ossification.

Therefore, an individualized treatment plan has to be defined for elderly patients following acetabular fractures.

3.5. Surgical options

There are ardent proponents of surgical management as well. Traditional philosophy and teaching have been in favour of operative intervention for displaced acetabular fractures in elderly patients if they are appropriate surgical candidates. 20, 21, 22

3.6. Rationale

Some of the older literature have highlighted poor results with nonoperative treatment of displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly population. 30 The rationale to support surgical management has been the concern about elderly patients not being able to mobilise with conservative treatment due to pain issues and the consequent risks of recumbency.

Surgical treatment is often stated to allow more rapid mobilisation and earlier return to ambulation, although this assertion remains unproven from good quality comparative studies. 61,63

It is important at this stage to note the difference between many traditional principles of non-surgical management which hinged on prolonged recumbency or traction as opposed to modern functional conservative treatment within multidisciplinary teams supporting proactive medical management and early ambulation.

The rate of secondary conversions to total hip replacement in elderly patients with acetabular fractures has been reported to be 12.4% and this was not affected by initial conservative or surgical treatment (Wollmerstadt).

4. Methods

4.1. Surgical treatment options include the following-

-

I.

Percutaneous screws osteosynthesis (PSO).

-

II.

Open Reduction and internal Fixation.

-

III.

Acute “Fix and Replace”/Acute THR without osteosynthesis.

-

IV.

Delayed THR (this will not be discussed in detail in this review).

-

(i)

Percutaneous Screw Osteosynthesis

Percutaneous screw osteosynthesis (PSO) (Fig. 4) has been recommended in older patients with non-displaced or minimally displaced acetabular fractures where pain is difficult to manage and early mobilisation is of paramount importance. Some authors recommend operative stabilisation of non-displaced fractures if patients cannot be effectively mobilised within one week of injury due to pain. 23,24,26

Fig. 4.

Anterior and posterior column percutaneous screws of minimally displaced acetabulum fracture.

The rationale is that percutaneous screws would reduce the pain and allow early mobilisation. 25 Multi-morbid patients with reduced compliance, who are not able to perform partial weight bearing are stated to benefit from PSO.

The surgical techniques of percutaneous screw fixation have been well-described. 23,24,26 Minimal invasive techniques have obvious benefit of decreased blood loss, decreased surgical insult and potentially less morbidity to patients. However the procedure does require skill and experience and are not necessarily quicker when multiple percutaneous screws are required. An average operating time of 70 min and an average blood loss of 100 mL have been reported with experienced teams although these times can be much longer in bilateral cases.

Whilst one has to sacrifice anatomic reduction, Starr et al. 23, 24, 26 a describe limited open reduction techniques using stab incisions, ball-spike pushers and modified clamps to achieve reduction and percutaneous screw fixation. The goals are to minimise the surgical insult from extensive soft tissue dissection and lower the systemic risk of complications. At the same time this approach may allow better pain relief and earlier mobilisation. The authors accept some non-anatomic reductions in their elderly patients with the aim of obtaining sufficient stability to allow healing and facilitate a THA at a later stage.

There is difficulty in finding comparative good quality outcomes literature demonstrating superior outcomes. In a meta-analysis, Daurka et al. reported a significantly higher mortality rate of 30.5% after PSO in patients >55 years. 23, 24, 26 The follow up period in PSO group, however was significantly longer and the procedure was more commonly performed in patients with a reduced general condition and more frequent comorbidities.

-

(ii)

Open reduction Internal Fixation

In their seminal text on acetabular fractures, Letournel and Judet reported 120 fractures in patients older than sixty years old, of which 103 underwent open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). They reported 76% good to excellent clinical results, and cautioned against abandoning the older patient to nonoperative treatment. 23, 24, 26

Helfet et al. demonstrated 83% (15 out of 18) good to excellent results in a small series of patients treated surgically. 23, 24, 26

Surgery may be more appropriate for displaced fractures involving the weight-bearing dome of the acetabulum in ambulatory adults where the recommended goal has been anatomic reduction and stable internal fixation where such fixation is possible. Stabilisation. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

The reported results suggest the presence of a lasting reconstruction in 69% patients at an average follow up of more than 5 years. 22

Equally it must be recognised that there is a high incidence of poor outcomes and failure of surgical fixation, and comparative data demonstrating superior efficacy is lacking (Helfet). Predictors of poor outcomes treated with ORIF in acetabular fractures at any age have been identified by Mears et al. These include intraarticular comminution (10 or more fragments) with full-thickness abrasive loss of the articular cartilage of the femoral head; impaction of the femoral head; impaction of the acetabulum involving greater than 40% of the joint surface including the weight-bearing region; pre-existing severe degenerative arthritis with a complete loss of articular cartilage and loss of hip joint congruity; displaced comminuted fracture of the femoral head; or, completely displaced fracture of the femoral neck.

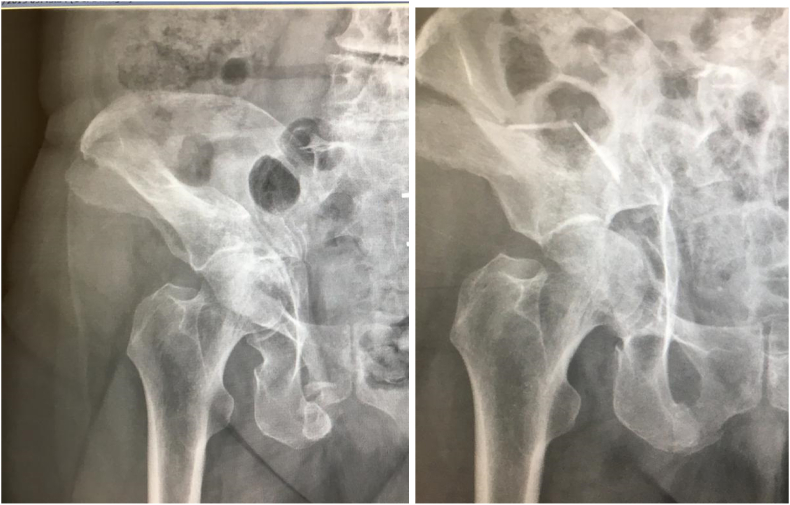

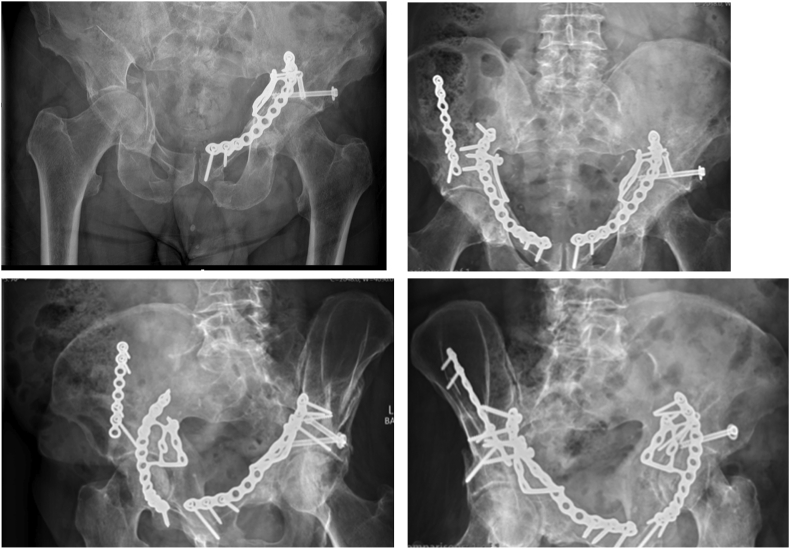

The principles and techniques of ORIF are not-dissimilar to those in younger patients (Fig. 5). 31, 32, 33 Accurate anatomic reduction if more difficult to obtain and maintain in comminuted osteoporotic bone.

Fig. 5.

a – Right comminuted acetabulum fracture – associated both column, left acetabulum fixed 2 years earlier. The patient present with a new fracture of the right acetabulum. b, c, d. ORIF right acetabulum via AIP and first window of ilioinguinal.

There is often the need to provide good stable buttressing to the medially displaced quadrilateral plate and anteriorly displaced anterior column fractures using specially designed plates via the anterior -intra pelvic approach (Fig. 5). Locking implants have also been recommended on the basis that they provide better fixation in osteoporotic bone. However, there is again scarce data demonstrating the efficacy of these more expensive implants as opposed to conventional reconstruction plates.

4.2. The superomedial dome fragment

Certain radiological signs which highlight specific patho-anatomic lesions are recognised to be poor prognostic factors for survivorship of the native joint. Poor prognosis for survival of the hip joint is affected by comminuted posterior-wall fractures with marginal impaction or involvement of the weight bearing dome, displaced transrectal transverse fractures, femoral-head impaction lesions, or significant subluxation and instability of the hip joint.

Anglen et al. have described that the “Gull Sign” is a harbinger of failure of internal fixation of geriatric acetabular fracture. 34 They described 100% predictor of failure of fixation and advised for consideration of acute THR.

However, this may be related to a failure to achieve accurate and stable reduction of the superomedial dome impaction fragment. LaFlamme 35 et al. opine that direct access to the impacted dome fragment may not be achievable through the ilioinguinal approach resulting in incomplete reductions due to failure in correcting the posterior displacement of the fragment and the adjacent medially displaced quadrilateral plate. 58 Loss of reduction is also possible when the underlying metaphyseal defect remains unfilled. They believe that this is most likely to negatively affect the prognosis.

Unreduced impacted fragments of the dome not only leave an incongruent hip joint surface but also lead to instability. As with most intraarticular fractures, an arthrotomy is preferable when reducing osteochondral fragments.

The authors recommend that after the articular fragments are reduced, the underlying defect should be filled with cancellous autograft, a corticocancellous bone block, or a bone substitute to support the elevated fragments and help to avoid failure under axial load.

They showed that direct reduction technique for superomedial dome impaction through the anterior intrapelvic approach (modified Stoppa) yields better results in this population group (Fig. 5).

4.3. Outcomes

The larger of the published series, with average follow-up of 5 years, demonstrate a significant conversion rate to total hip arthroplasty of up to 31%. [Helfet, O’Toole)]

In a comparative study, Walley et al. 63 found that operative patients did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in mortality within 1 year of treatment compared to non-operatively treated patients. But operative patients did demonstrated a statistically significant increase in treatment failure marked by a conversion to a THA within 1 year when compared to conservatively treated patients.

In a series of 147 patients treated with ORIF from a level I trauma centre, O’Toole et al. 64 reported that 28% underwent hip arthroplasty an average 2.5 years after injury in the 46 patients that could be followed up. 37 Despite the loss to follow up, the authors state that their protocol of mostly ORIF showed a high 1-year mortality rate of 25% and a rate of conversion to arthroplasty after ORIF of 28%.

In a multi-centre study, Gary and O’Toole 64 did not find surgery to be an advantage in reducing mortality. The argument that conservative management would lead to a higher mortality is difficult to substantiate from currently available evidence. O’Toole et al. state that the operative treatment of acetabular fractures does not increase or decrease mortality once comorbidities are taken into account. In a multivariate analysis they found age more than 70 and Charles comorbidity index to be factors that significantly increase the hazard for mortality. They conclude that the decision for operative versus nonoperative treatment of geriatric acetabular fractures should not be justified based on the concern for increased or decreased mortality alone.

Schnaser 65 reported on 171 fractures in patients older than 60 years. Of the 10% that were converted to THR there were 13 who had undergone ORIF and 3 that were treated non-operatively.

-

(iii)

Fix and replace – the combined hip procedure

It has been recognised that ORIF by itself is not only challenging in elderly patients with comminuted fractures in osteoporotic bone, but also associated with higher complication rate, failure of fixation and secondary conversion procedures to THA (Boelch et al.).

One study comparing the outcome of fixation alone, against fixation and replacement at minimum of 2 years reported only 28.6% hip joint survival in the fixation group compared with 100% in the replacement group. 56 Another comparative study reported secondary hip replacement in 45% of the fixation cases. 57

Therefore, logically, if surgery is identified to be the appropriate option for the patient, one could make a case for stabilisation the fracture and performing the THA at the same time. 29,40

The concept was pioneered by Mears et al. about 2 decades ago. The principles revolve around achieving stable fixation of the acetabular columns using a single or two approaches. The fixation should be stable enough to allow the acetabular component to be fixed to the reconstructed acetabulum. Older techniques consisted of intra-pelvic wires and anti-protrusion cages and reasonably good outcomes were reported in the short term. More recent availability of ultra-porous acetabular components, and improved understanding or surgical principles and techniques has allowed further refinement of this idea.

4.4. Indications

The indications of “fix and replace” for acute acetabular fractures are not clearly defined. Most of the studies 39 indicate that combined acute THR (alone or in combination with ORIF) is the preferred treatment in patients with the following factors - complex fractures (according to Letournel and Judet), concurrent osteoarthritis of the hip, associated femoral head fractures, pathological fractures, significant cartilage damage, poor bone quality because of osteopaenia or osteoporosis, non-reconstructable fractures.

Another study has divided the indications into fracture related and patient related factors. 40

| Patient factors | Age |

| Osteoporosis | |

| Obesity | |

| Low functional demand | |

| Pre-existing ipsilateral osteoarthritis of the affected hip | |

| Previous arthroplasty to the contralateral hip | |

| Fracture personality | Severe posterior wall comminution |

| Articular cartilage damage to femoral head | |

| Marginal impaction of the acetabulum | |

| Ipsilateral displaced femoral head or neck fractures | |

| Anterior head dislocation | |

| External factors | Prolonged hip dislocation |

| Delay to reconstruction |

A recent review of surgical management of acetabular fractures has identified certain characteristics as negative prognostic factors in predicting clinical outcome41:

-

(i)

Patient age >40.

-

(ii)

Poor fracture reduction (>3 mm).

-

(iii)

Multi-fragmentary fractures of the posterior/anterior wall.

-

(iv)

Transverse multi-fragmentary fractures of the tectum.

-

(v)

Cartilage damage to the femoral head and/or acetabulum.

-

(vi)

Initial fracture displacement >20 mm.

-

(vii)

Delay to surgery >5 days and >15 days for associated and elementary fractures respectively.

These factors along with associated patient factors should be taken into consideration for the decision to fix and replace for these complex injuries.

4.5. Techniques

Various techniques have been described in literature to allow acute implantation of the prosthetic hip joint into a fractured acetabulum. These techniques have evolved in the last 2-3 decades. The techniques were reviewed in a recent review article by Manson. 62

Stable osteosynthesis of the columns with neutralisation and buttressing plates is essential before proceeding to the arthroplasty in most cases. Regardless of which philosophy or technique is chosen, instability of the bone fragments/columns is shown to threaten stable prosthetic fixation, hence primary fracture stability of fixation is of paramount importance39, 40, 41.

Earlier techniques by Mears 29 and Mouhsine et al. 43 utilised additional cable fixation and lag screw fixation. Others have used the Burch-Schneider anti-protrusion cage together with bone grafting to provide for implantation of the THR 44. The prosthesis alone can also be used for the management of certain acetabular fractures as demonstrated by Sermon et al.42

Herscovici et al. describe their operative management as stabilisation of the fracture using standard ORIF techniques, approached via either the Kocher Langenbeck (n = 19) or Ilioinguinal (n = 3) approach45. A variety of options were described over a twenty year period by Sarker et al. 46 ranging from standard plate fixation to reinforcement with anti-protrusio cage devices.

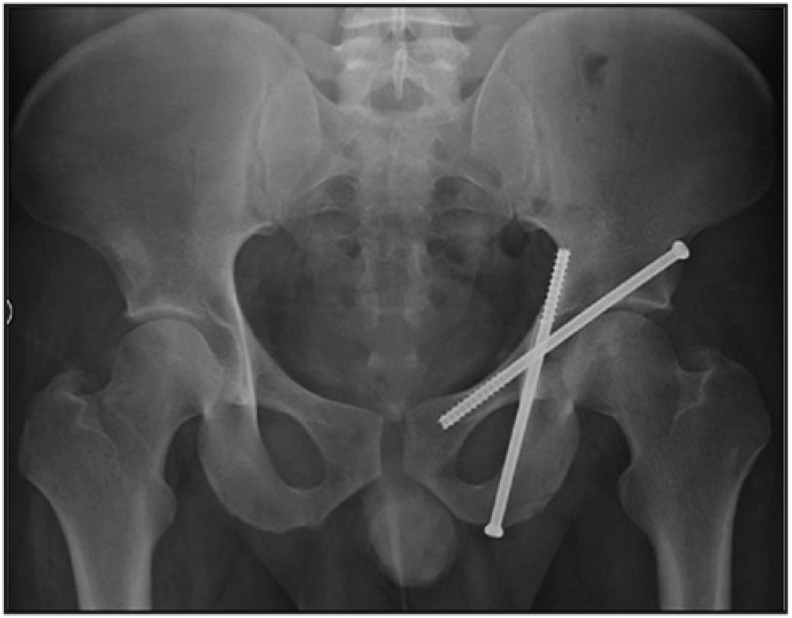

Over a period of time two main strategies have evolved. The anterior column fracture can be separately fixed using an anterior approach such as the (anterior intra-pelvic) followed by a second posterior approach to additionally fix the posterior column and implant the hip arthroplasty. Alternatively (which is our preference) a single posterior approach can be utilised to stably fix the acetabulum (usually with two plates) followed by insertion of the acetabular component (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

a, b, c – comminuted left acetabulum fracture fixed using a single posterior approach and cementless ultra-porous reconstruction with bone graft.

Rickman et al. 47 reported using separate anterior and posterior column plate fixation with simultaneous THA using an ultra-porous tantalum socket and a cemented femoral stem. Similar surgical approach was used by Tissingh et al. 38 using open reduction and internal fixation of the anterior fracture component (through a modified Stoppa approach) followed by posterior column reconstruction with a hip replacement. Femoral head bone graft has been used for posterior wall defects in some studies to provide additional support to the acetabular component. 48

Various combinations of implants for hip replacements have been used as well. Most authors have recommended a revision type porous shell with multiple screw options for the acetabular component. 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 A cemented liner can be fixed into the shell. Large-diameter femoral heads and/or elevated or dual-mobility liners have been used in this patient group to optimise stability. Standard femoral stem can be used for the hip replacement depending on surgeon’s choice and experience. Most studies tend to use a cemented highly polished double-tapered stem or an uncemented stem. Yet others have used Cup-cage constructs 50 and use of Custom built roof reinforcement plates in one series. 51

Fig - showing a comminuted fracture of the left acetabulum with hip dislocation and cartilage loss treated with posterior column plating using two plates for better rotational control, a porous Tantalum acetabular component (TMARS, Zimmer), and a cemented C-stem (DePuy).

4.6. Outcomes and complications

It is difficult to find comparative studies to guide management decisions. It is also difficult to find studies showing superiority of this philosophy and technique over the conservative philosophy. Majority of the studies report a high complication rate with this philosophy.

Outcome of acute hip replacement for acetabular fractures is difficult to compare, as most of the studies are retrospective case series and use a variety of different indications and different techniques.

In a systematic review of outcomes after simultaneous fixation and replacement in elderly patients with acetabulum fractures, and studies with patients undergoing fixation alone, operative times were longer, and blood loss was greater for the former group, but no difference was noted in mortality between the groups. 1

Another systematic review (De Bellis) showed good Harris Hip Scores (Mears, Tidemark, Herscovici reporting HHS of 89, 85 and 74 respectively). However there were no control groups for comparison in these studies.

Sermon et al. 52 and Chémaly et al. 53 are studies which try to directly compare acute and late hip replacement for acetabular fractures. Sermon et al. compared the results of primary hip replacement in patients with an average age of 78 years with those of delayed replacement in patients with an average age of 53 years. A reduced revision rate (8% compared with 22%) and a reduced occurrence of heterotopic ossification (28% compared with 41%) were observed in the acute group compared with the delayed group. However, there were more patients with subjectively excellent or good results according to the Harris hip scores in the delayed replacement group compared with in the acute group (76% compared with 58%). However, none of these differences were statistically significant. Sermon et al. reported a 25% overall complication rate but did not divide this between the two groups.

Chémaly et al. did not have any patients in either group who required revision. They found heterotopic ossification occurred eight times more in the acute group contrary to the Sermon et al. study. Chémaly et al. also found more than double the blood loss (992 mL vs. 416 mL) and operating time (171 min vs. 76 min) in the acute group. They had a complication rate of 25% in the acute group and 15% in the late group, but this was not analysed statistically.

Aseptic loosening of the acetabular component has classically been the concern with regard to performing an acute hip replacement for acetabular fracture. A systematic review of over 40 studies involving around 300 cases 54 found revision for aseptic loosening occurred at a rate of 2.3% (range 0%–10%) albeit with a mean follow up of only 53.7 months (range 18–81.5 months). In this study, the average Harris hip score was 87 (range 42–99), but the proportion of good and excellent results varied from 100% to just 60%.

Presence of heterotopic ossification was the most recurrent complication in the studies considered from systematic review of De Bellis et al., and ranged from 10% to 40%. The dislocation rate ranged from 0% to 14%. In this review, the highest revision rate (42%) together with the highest prevalence of radiographic loosening (21%) was reported by Sarkar et al.. Herscovici et al. reported the highest rate of dislocations (14%). De Bellis et al. concluded that there is currently a limited evidence base for THR in patients with acetabular fractures; therefore, physicians’ practice and expertise are the most useful tools in clinical practice.

Systematic reviews and studies have reported different mortality rates as well. The most recent review 54 reported the overall complication rate of 20.1% ranging from no complications to 59%. The mean mortality was 9%, with some authors reporting no deaths and the highest 58% at 3 years, with 26% in the first year. 55 Unfortunately, most of the systematic reviews are based on case series with no comparative group.

Borg et al. 56 reported a short term follow up of two groups of patients treated either with ORIF or with the combined hip procedure. The combined hip procedure (CHP) gave a hip survival rate of 100% after three years, compared with 28.6% hip joint survival in the ORIF group. No dislocations or deep infections occurred in the CHP group. Patient survival was lower in the CHP group after three years. There were no relevant differences in patient-reported outcomes.

Weaver et al. 60 evaluate the rate of revision surgery in elderly patients with acetabular fractures treated with ORIF or THA and reported a higher rate of reoperation (30%) with ORIF compared with those treated with THA (14%). The numbers did not reach statistical significance to show a difference between the two groups. They concluded that acute reconstruction of acetabular fractures with THA in the geriatric population compared favourably with ORIF, with a similar rate of complications, but with improved pain scores. They found a high rate of conversion to THA within 2 years of injury when patients were treated with ORIF.

Giunta et al. 61 reported their technique of plating both columns and a simultaneous THA at a mean follow up of 4 years. This paper showed a post-operative complication rate of 74% (20 in 27 patients) with a 7% mortality.

4.7. Summary

Acute fixation and replacement for acetabular fractures may be a viable treatment method for managing acetabular fractures in properly selected patients with reasonable outcomes at short-term follow-up.

The indications are not well defined but various patient related and fracture related factors (where ORIF alone would give a poor outcome) should be taken into consideration in decision making. The quoted complication rates are significant and should be taken into consideration when counselling patients.

Various fixation techniques have been described, however good column fixation prior to acetabular shell implantation appears to provide improved outcomes based on multiple studies. These are complex and technically demanding operations with increased blood loss and a longer surgical time. A significant degree of expertise and experience in acetabular fixation techniques and arthroplasty is essential.

It must be appreciated that a simultaneous fixation of the acetabulum and replacement is a major surgical insult to many elderly frail patients and long term data of the superiority of this philosophy is lacking. These cases are technically demanding with an average operative time of 174 min (range 45–510 min) and blood loss of 964 ml (range 200–5000 mL) as shown in the literature. There are also risks of significant complications in about 20% of cases and mortality rate of up to 10%.

These factors are not only important in decision making but also counselling the patients in terms of the risks and benefits of a surgical philosophy against a more conservative approach.

5. Discussion

We have tried to present a narrative evidence based review of various approaches to manage geriatric acetabular fractures and indicated our preferred strategies based on experience and available evidence. It is difficult to find evidence based algorithms to guide management.

Carroll et al. 36 recommend early medical and anaesthetic evaluation of elderly patients with acetabular fracture for operative risks as these patients have less physiological reserve than younger patients to tolerate major surgery. If deemed suitable for surgery then the treatment determinant will be the fracture and injury variables. If the fractures are displaced and not amenable to percutaneous fixation, then formal ORIF is recommended if the patients can tolerate the surgery (completed reasonably within 3–4 h’ time).

Henry et al. 59 recommend non-surgical management for minimally displaced and/or stable fractures, concentric hip joint, very limited preinjury functional status (non-ambulatory), severe medical comorbidities in patients who are or unlikely to tolerate a surgical procedure. The authors do not recommend prolonged bed rest or traction. In some of these cases they suggest a planned staged strategy for delayed THA when needed. With this approach, fracture fixation is not critical as arthroplasty becomes less extensive after fracture healing. A patient with a completely incongruous hip joint according to these authors should be considered for immediate fracture fixation and concomitant total hip replacement so that the patient can be mobilised as soon as possible. They also highlight that acute THA can be challenging procedures requiring revision hip arthroplasty and fracture fixation expertise.

We believe that proactive medical optimisation of the patient by a multi-disciplinary team should be started on admission even if conservative management may be ultimately selected. This allows the patient to be prepared for surgery in case the treatment decisions need to be changed. It also helps in better recovery and pain management for those that continue with non-surgical management.

We prefer to manage the vast majority of our undisplaced and minimally displaced acetabular fractures conservatively using the concept of functional conservative treatment and early mobilisation as described.

In rare situations, an undisplaced fractures can be considered for percutaneous fixation if the patient cannot be effectively mobilised within one week of injury or if pain becomes a major issue or cases of bilateral fractures. However with good medical and pain management we find this situation uncommon. It is rare to find that they are still in a lot of pain at 1 week. But we do not disagree that where pain is difficult to manage then selective consideration may be given to percutaneous screw fixations or limited open reduction techniques.

Predominantly anterior based injuries are more common in elderly patients (anterior column, anterior wall, anterior column with posterior hemi transverse). They are also commonly associated with supero-medial dome impaction injuries. These injuries are more challenging to manage with an acute fix and replace strategy according to many authors without using two separate approaches.

Where surgery is feasible, an anterior ORIF of displaced acetabular fracture in elderly patients with good reduction of the superomedial dome is a reasonable alternative. However it must be appreciated that a number of these cases treated by ORIF alone are at risk of conversion to a total hip replacement.

It is important to balance the goal of obtaining an open reduction with fairly extensive surgery against the challenges of achieving stable fixation in osteoporotic comminuted fractures with a risk of secondary conversion to a total hip replacement in any event in a significant proportion of these cases.

In some cases with extensive displacement one may have to perform ORIF as the first stage surgery just to achieve stable continuity of the acetabular columns (if possible using a predominant anterior approach). The limited goals here is to make the “acetabulum look like an acetabulum” and accept a degree of non-anatomic reduction so as to facilitate a subsequent THA (usually with a posterior approach through intact surgical territory) in a more “anatomic looking” acetabulum.

However, in our preference, based on the available evidence of the failure rate of formal ORIF in elderly osteoporotic fractures and the need for conversion to THA, we find ORIF alone to be an uncommon treatment option. We would not hesitate to treat many of these displaced fracture conservatively (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3). We find that despite radiologically unsatisfactory appearances, the incidence of sufficient symptoms warranting further surgery is uncommon (as also shown by Schnaser et al. and O’Toole et al.) and functional outcomes are surprisingly good.

Our preferred indications for the combined hip procedure/acute fix and replace philosophy include acetabular fractures in elderly patients where the patient would tolerate and benefit from major surgical reconstruction to allow early ambulation, and where the fracture is not amenable to conservative management because of reasons such as - crushed unreconstructable posterior wall or superior dome fractures, dislocated unstable femoral heads, extensively damaged cartilage usually on either side, associated femoral head of femoral neck fractures, delayed presentations, peri-prosthetic acetabulum fractures, and importantly, where the fracture allows stabilisation and replacement using a single posterior approach.

We do believe that using two simultaneous approaches causes extensive disruption of the natural fascial barriers between the intra-pelvic structures and the hip joint and we believe this factor could be responsible for the cases of intra-pelvic extensive sepsis that we have come across after the fix and replace philosophy using two approaches.

Where the anterior column may be unstable, we find that using two posterior column plates gives adequate rotational stability to both columns, and when combined with an ultra-porous acetabular component with multiple screws, a separate anterior approach is rarely indicated. When necessary, we prefer to stabilise the anterior column component of the fracture using the posterior Kocher-Langenbeck approach using an anterior column screw intra-operatively and under vision. Once the femoral head has been excised good visualisation is provided to insert the anterior column screw. In our experience the (Zimmer) TMARS acetabular component allows drilling through the acetabular shell and position an additional anterior column screw into the pubic ramus through the shell if needed. This affords excellent triangular purchase of the component to the ilium, ischium and pubis and negates the need for a second approach.

However this philosophy using two separate approaches also has its proponents and reasonable outcomes have been reported by Rickman.

In the rare scenarios, where both columns are very comminuted but the head remains largely under the weight bearing dome, we have preferred to allow a trial of conservative management and early ambulation and allowing the fracture to become sticky or heal over the next few weeks to months. A relatively straightforward THA can then be performed without compromising long term results in a small number of these patients.

Our approach has evolved based on experience of seeing good outcomes with conservative management. We have seen that simultaneous anterior and posterior surgery is often not tolerated by frail elderly patients and there is a significant risk of surgical complications such as infection and dislocation. A high complication rate is also borne out by the available literature which shows increased risks of heterotopic ossification and aseptic loosening.

In the absence of good quality evidence in favour of surgery, we urge a cautious approach when it comes to considering fairly major and aggressive surgical philosophies in this vulnerable group of patients which needs to be balanced against conservative management.

We have developed and continue to use a pragmatic patient-oriented approach in selecting the appropriate procedure that takes into consideration the otherwise fairly good natural history of functional conservative treatment of fractures in our experience in majority of patients, as well as the perceived advantages of the fix and replace philosophy in carefully selected patients.

References

- 1.Daurka J.S., Pastides P.S., Lewis A., Rickman M., Bircher M.D. Acetabular fractures in patients aged > 55 years: a systematic review of the literature. Bone Joint Lett J. 2014 Feb;96-B(2):157–163. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B2.32979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson T.A., Patel R., Bhandari M., Matta J.M. Fractures of the acetabulum in patients aged 60 years and older: an epidemiological and radiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Feb;92(2):250–257. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a) Cecil a W Yu, Rodriguez V.A., Sima A., Torbert J., Satpathy J., Perdue P., Toney C Kates S. High- versus low-energy acetabular fracture outcomes in the geriatric population. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2020 Jul;11:1–6. doi: 10.1177/2151459320939546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fölsch C., Alwani M.M., Jurow V., Stiletto R. Surgical treatment of acetabulum fractures in the elderly. Osteo or Endo Unfall. 2015 Feb;118(2):146–154. doi: 10.1007/s00113-014-2606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller J.M., Sciadini M.F., Sinclair E., O’Toole R.V. Geriatric trauma: demographics, injuries, and mortality. J Orthop Trauma. 2012 Sep;26(9) doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182324460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanschen M., Pesch S., Huber-Wagner S., Biberthaler P. Management of acetabular fractures in the geriatric patients. SICOT J. 2017;3:37. doi: 10.1051/sicotj/2017026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer R.F. Acetabular fractures in older patients. J Bone Jt Surg [Br] 1989;71B:774–777. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B5.2584245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manson T., Schmidt A.H. Acetabular fractures in the elderly: a critical analysis review. JBJS Rev. 2016 Oct 4;4(10) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.15.00090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antell N.B., Switzer J.A., Schmidt A.H. Management of acetabular fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. August 2017;25(8):577–585. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butterwick D., Papp S., Gofton W., Liew A., Beaulé P.E. Acetabular fractures in the elderly: evaluation and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015 May 6;97(9):758–768. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mears D.C. Surgical treatment of acetabular fractures in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999 Mar-Apr;7(2):128–141. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zha G.C., Sun J.Y., Dong S.J. Predictors of clinical outcomes after surgical treatment of displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Res. 2013 Apr;31(4):588–595. doi: 10.1002/jor.22279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagenkopf E., Grose A., Partal G., Helfet D.L. Acetabular fractures in the elderly: treatment recommendations. HSS J. 2006 Sep;2(2):161–171. doi: 10.1007/s11420-006-9010-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll E.A., Huber F.G., Goldman A.T., Vir kus W.W., Pagenkopf E., Lorich D.G., Helfet D.L. Treatment of acetabular fractures in an older population. J Orthop Trauma. 2010 Oct;24(10):637–644. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181ceb685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman S.M., Mendelson D.A., Bingham K.W., Kates S.L. Impact of a comanaged Geriatric Fracture Center on short-term hip fracture outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Oct 12;169(18):1712–1717. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wollmerstädt J., Pieroh P., Schneider I., Zeidler S., Höch A., Josten C., Osterhoff G. Mortality, complications and long-term functional outcome in elderly patients with fragility fractures of the acetabulum. BMC Geriatr. 2020 Feb 17;20(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1471-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanderschot P. Treatment options of pelvic and acetabular fractures in patients with osteoporotic bone. Injury. 2007;38:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tornetta P., 3rd Non-operative management of acetabular fractures. The use of dynamic stress views. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999 Jan;81(1):67–70. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b1.8805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan S.P., Manson T.T., Sciadini M.F., Castillo R., Muppavarapu R., Schurko B., OʼToole R. Functional outcomes of elderly patients with nonoperatively treated acetabular fractures that meet operative criteria. Multi-centre study. J Orthop Trauma. 2017 Dec;31(12):644–649. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magu N.K., Rohilla R., Arora Conservatively treated acetabular fractures: a retrospective analysis. Indian J Orthop. 2012 Jan;46(1):36–45. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.91633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Letournel E., Judet R. second ed. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1993. Fractures of the Acetabulum. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helfet D.L., Borrelli J., DiPasquale T. Stabilization of acetabular fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:753–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matta J.M., Anderson L.M., Epstein H.C., Hendricks P. Fractures of the acetabulum: a retrospective analysis. Clin Orthop. 1986;205:241–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gay S.B., Sistrom C., Wang G.J., Kahler D.A., Boman T., McHugh N. Goitz HT Percutaneous screw fixation of acetabular fractures with CT guidance: preliminary results of a new technique. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992 Apr;158(4):819–822. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.4.1546599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starr A.J., Reinert C.M., Jones A.L. technique. J Orthop Trauma. 1998 Jan;12(1):51–58. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a) Starr A.J., Jones A.L., Reinert C.M. Preliminary results and complications following limited open reduction and percutaneous screw fixation of displaced fractures of the acetabulum. Injury. 2001;32(Suppl 1):SA45–SA50. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(01)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harper C.M., Lyles Y.M. Physiology and complications of bed rest. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988 Nov;36(11):1047–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazemi N., Archdeacon M.T. fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012 Feb;26(2):73–79. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318216b3e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gary J.L., Lefaivre K.A., Gerold F., Hay M.T., Reinert C.M., Starr A.J. Survivorship of the native hip joint after percutaneous repair of acetabular fractures in the elderly. Injury. 2011 Oct;42(10):1144–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buller L.T., Lawrie C.M., Vilella F.E. A growing problem: acetabular fractures in the elderly and the combined hip procedure. Orthop Clin N Am. 2015;46:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mears D.C., Velyvis J.H. Acute total hip arthroplasty for selected displaced acetabular fractures: two to twelve-year results. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2002;84– doi: 10.2106/00004623-200201000-00001. A:1–9, Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peter RE, Dayer R, N’Gueumachi PN, et al. Acetabular fractures in the elderly: epidemiology, treatment options, and outcome after nonoperative treatment. Poster Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association; October 18–20, ; Boston, MA.

- 31.Letournel E. Les fractures du cotyle, etude d’une serie de 75 cas. J Chir. 1961;82:47–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tile M. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1995. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matta J.M. Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively within three weeks after the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1632–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anglen J.O., Burd T.A., Hendricks K.J., Harrison P. The "Gull Sign": a harbinger of failure for internal fixation of geriatric acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2003 Oct;17(9):625. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200310000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laflamme G.Y., Herbert-Davies J. Direct reduction technique for superomedial dome impaction in geriatric acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2014 Feb;28(2):e39–e43. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318298ef0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carroll E.A., Helfet D.L. Fracture of Pelvis and Acetabulum. fourth ed. 2015. The elderly patients with an acetabular fracture; pp. 789–802. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Toole R.V., Hui E., Chandra A. How often does open reduction and internal fixation of geriatric acetabular fractures lead to hip arthroplasty? J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:148–153. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31829c739a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tissingh E.K., Johnson A., Queally J.M., Carrothers A.D. Fix and replace: an emerging paradigm for treating acetabular fractures in older patients. World J Orthoped. 2017;8(3):218–220. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.218. Published 2017 Mar 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Bellis U.G., Legnani C., Calori G.M. Acute total hip replacement for acetabular fractures: a systematic review of the literature. Injury. 2014 Feb;45(2):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.09.018. Epub 2013 Sep 20. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy C.G., Carrothers A.D. Fix and replace; an emerging paradigm for treating acetabular fractures. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2016;13(3):228–233. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2016.13.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziran N., Soles G.L.S., Matta J.M. Outcomes after surgical treatment of acetabular fractures: a review. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13:16. doi: 10.1186/s13037-019-0196-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sermon A., Broos P., Vanderschot P. Total hip replacement for acetabular fractures. Results in 121 patients operated between 1983 and 2003. Injury. 2008;39:914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mouhsine E., Garofalo R., Borens O., Blanc C.H., Wettstein M., Leyvraz P.F. Cable fixation and early total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of acetabular fractures in elderly patients. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tidemark J., Blomfeldt R., Ponzer S., Soderqvist A., Tornqvist H. Primary total hip arthroplasty with a Burch-Schneider antiprotrusion cage and autologous bone grafting for acetabular fractures in elderly patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;3:193–197. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herscovici D., Jr., Lindvall E., Bolhofner B., Scaduto J.M. The combined hip procedure: open reduction internal fixation combined with total hip arthroplasty for the management of acetabular fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Trauma. 2010 May;24(5):291–296. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181b1d22a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarkar M.R., Wachter N., Kinzl L., Bischoff M. Acute total hip replacement for displaced acetabular fractures in older patients. Eur J Trauma. 2004;30:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rickman M., Young J., Trompeter A., Pearce R., Hamilton M. Managing acetabular fractures in the elderly with fixation and primary arthroplasty: aiming for early weightbearing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:3375–3382. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3467-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sierra R.J., Mabry T.M., Sems S.A., Berry D.J. Acetabular fractures. The role of total hip replacement. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2013;95-B:11–16. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.32897. 11_Supple_A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malhotra R., Gautam D. Acute total hip arthroplasty in acetabular fractures using modern porous metal cup. J Orthop Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1177/2309499019855438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chou D., Abrahams J., Callary S., Costi K., Howie D., Solomon B. Trabecular metal cup-cage construct in immediate total hip arthroplasty for osteoporotic acetabular fractures. Orthop Proceed. 2018;100-B SUPP_9, 42-42. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Resch H., Krappinger D., Moroder P., Auffarth A., Blauth M., Becker J. Treatment of acetabular fractures in older patients-introduction of a new implant for primary total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137(4):549–556. doi: 10.1007/s00402-017-2649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sermon A., Broos P., Vanderschot P. Total hip replacement for acetabular fractures. Results in 121 patients operated between 1983 and 2003. Injury. 2008;39:914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chémaly O., Hebert-Davies J., Rouleau D.M., Benoit B., Laflamme G.Y. Heterotopic ossification following total hip replacement for acetabular fractures. Bone Joint Lett J. 2013;95-B:95–100. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.29721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamlin K., Lazaraviciute G., Koullouros M., Chouari T., Stevenson I.M., Hamilton S.W. Should total hip arthroplasty be performed acutely in the treatment of acetabular fractures in elderly or used as a salvage procedure only? Indian J Orthop. 2017;51(4):421–433. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_138_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chakravarty R., Toossi N., Katsman A., Cerynik D.L., Harding S.P., Johanson N.A. Percutaneous column fixation and total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of acute acetabular fracture in the elderly. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:817–821. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borg T., Hernefalk B., Hailer N.P. Acute total hip arthroplasty combined with internal fixation for displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly: a short-term comparison with internal fixation alone after a minimum of two years. Bone Joint Lett J. 2019 Apr;101-B(4):478–483. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B4.BJJ-2018-1027.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boelch S.P., Jordan M.C., Meffert R.H. Comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total hip replacement for osteoporotic acetabular fractures: a retrospective clinical study. Int Orthop. 2017;41:1831–1837. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Casstevens C., Archdeacon M.T., dʼHeurle A., Finnan R. Intrapelvic reduction and buttress screw stabilization of dome impaction of the acetabulum: a technical trick. J Orthop Trauma. 2014 Jun;28(6):e133–e137. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henry P.D.G., Kreder H.J., Jenkinson R. The osteoporotic acetabular fracture. Orthop Clin N Am. 2013 Apr;44(2):201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.01.002. Epub 2013 Feb 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weaver Michael J., Malcolm Smith Raymond, Lhowe David W Vrahas Mark S. Does total hip arthroplasty reduce the risk of secondary surgery following the treatment of displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly compared to open reduction internal fixation? A pilot study. J Orthop Trauma. 2018 Feb;32:S40–S45. doi: 10.1097/BOT.000000000000108. Suppl 1: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a) Manson Theodore T. Open reduction and internal fixation plus total hip arthroplasty for the acute treatment of older patients with acetabular fracture: surgical techniques. Orthop Clin North Am. 2017 Apr 7;51(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.08.006. 2020 Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jean-Charles Giunta, Camille Tronc, Gael Kerschbaumer, Michel Milaire, Sébastien Ruatti, Jerôme TonettI., Mehdi Boudissa. Outcomes of acetabular fractures in the elderly: a five year retrospective study of twenty seven patients with primary total hip replacement. Int Orthop. 2019 Oct;43(10):2383–2389. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4204-4. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Magala M., Popelka V., Božík M., Heger T., Zamborský V., Šimko P. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2015;82(1):51–60. [Conservative treatment of acetabular fractures: epidemiology and medium-term clinical and radiological results] [Article in Slovak] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walley K.C., Appleton P.T., Rodriguez E.K. Comparison of outcomes of operative versus non-operative treatment of acetabular fractures in the elderly and severely comorbid patient. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2017 Jul;27(5):689–694. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1949-1. Epub 2017 Apr 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ebrahim Gary Joshua L Paryavi, Gibbons Steven D., Weaver Michael J., Morgan Jordan H., Ryan Scott P., Starr Adam J., OʼToole Robert V. Effect of surgical treatment on mortality after acetabular fracture in the elderly: a multicentre study of 454 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2015 Apr;29(4):202–208. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schnaser Erik Scarcella Nicholas R Vallier Heather A. Acetabular fractures converted to total hip arthroplasties in the elderly: how does function compare to primary total hip arthroplasty? J Orthop Trauma. 2014 Dec;28(12):694–699. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]