Abstract

Osteosynthesis of the acetabulum is complex and requires very careful planning and preoperative preparation. The goal is to achieve anatomical reduction without steps or gaps in the articular surface. If it has not been possible to achieve an optimal reconstruction, one has to consider whether it makes sense to carry out reosteosynthesis or revise the fixation. The risk of infection, heterotopic ossification, avascular necrosis of the femur and cartilage damage is much higher than with the primary procedure. Often, especially in older patients, it may make more sense to achieve fracture union and to implant a total hip prosthesis in due course. In younger patients, every attempt should be made to achieve optimum anatomical reduction and this may mean consideration of reosteosynthesis after careful planning and counselling of the patient. If reosteosynthesis is considered adequate imaging including a postoperative CT is essential as part of the planning. This article looks at the possible solutions for failed osteosynthesis of the acetabulum.

Keywords: Reosteosynthesis, Acetabulum, Arthrosis, Hip prosthesis, Incongruency, Plate osteosynthesis

1. Introduction

Fractures of the acetabulum are challenging to treat and can lead to post-traumatic arthrosis, femoral head necrosis or non-unions. Open reduction and anatomical reduction can significantly reduce the risk of post-traumatic arthrosis. The basic prerequisite for an achieving optimum reduction and an excellent/good outcome is meticulous planning, correct classification of the fracture and sufficient experience in the surgical approaches and reduction techniques used to manage these fractures. The entire team should be experienced in managing and carrying out such interventions regularly if the best outcome is to be achieved. This may include a minimum number of cases that are treated each year or designation of pelvic and acetabular reconstruction units so that the cases and experience are concentrated in order to maintain high standards and level of experience. A complete set of pelvic instruments with appropriate reduction instruments and a radiolucent table are just some prerequisites. It can also be helpful to use a 3D image intensifier to carry out a 3D scan intraoperatively in order to confirm accuracy of reduction or to rule out an intra-articular screw.1

Nevertheless, even with careful planning and precise execution of osteosynthesis arthrosis can develop. The reasons for this may be related to primary damage to the cartilage, impaction injuries and some preexisting arthritic changes in the joint. Failure after open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in acetabular fractures varies with the occurrence of post-traumatic arthrosis between 12% and 57%.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 A postoperative CT should always be performed in order to be able to analyze the result precisely. CT is clearly superior to conventional X-rays in the detection of any postoperative mal reductions. A significant number of patients with apparently anatomical reduction have an incomplete or poor reduction after CT. In a previous study we were able to show that in 42% of the patients who were assumed to have an anatomical reduction by a simple X-ray examination, the reduction was either imperfect or poor on CT evaluation.7 Archdeacon and Dailey8 followed up 606 patients. The evaluation of 563 postoperative pelvic CT scans led to a revision in 2.5% of the patients (n = 14). There were 6 (1.1%) cases of intra-articular hardware that were not detected during intraoperative fluoroscopy or pelvic radiographs. Four patients (0.7%) had residual intra-articular osteochondral fragments that were considered too large to retain in the hip joint. There were 3 cases (0.5%) of unacceptable incongruity and 1 case (0.2%) of both imperfect reduction and an intra-articular osteochondral fragment. The rate of revisions surgery after a post-operative CT is low, but it can be very helpful to confirm the accuracy of reduction, identify any mal positioned hardware and to learn and improve future reductions.

2. Questions to consider before contemplating revision surgery

If a reduction and stabilization is not optimal, the question arises whether, when and how revision surgery should be carried out. This decision depends on many factors. The first question you have to ask yourself is can I improve the reduction and will this improve the outcome for the patient. Is there something that was not appreciated or overlooked during the initial surgery and could this be addressed to improve the final result. Other factors to take into consideration include patient age, any preexisting osteoarthritis, patients’ physiological status, and any history of infection. If the patient had preexisting symptoms related arthritis prior to the injury then it may make sense to combine osteosynthesis and implantation of a prosthesis.

Any revision surgery will significantly increase the possible risk of infection and heterotopic ossification, especially with posterior approaches, dual approaches or extensile approaches. The overall incidence of radiological heterotopic ossification is up to 47% and it is not uncommon for approximately 15% these patients to develop symptoms.9,10 In revision surgery, the risk increases significantly. Similarly, the risk of infection and the risk of nerve injuries, which are usually around 3–4%,11 are increased during revision surgery. The risk of femoral head necrosis also increases with revision of osteosynthesis on the acetabulum. Being aware of these risks, one must carefully consider whether it is in the best interest of the patient to undergo revision surgery.

There are certain situations which may make revision surgery inevitable. These may include, for example, intra-articular screw penetration, which would result in abrasion of the femoral head or restrict movement, or retained free fragments in the joint that could lead to accelerated arthrosis. Other factors that might necessitate further surgery include infection, non-union of the acetabular fracture or progressive loss of fixation leading to instability.

Certain fracture configurations from the outset have a very high risk of ending up requiring a prosthesis. It is possible to predict the probability of needing a total hip prosthesis if certain criteria are known.12,13 A number of parameters are taken into account. Age, posterior wall involvement, initial dislocation, degree of cartilage damage to the femoral head, extent of marginal impaction, and use of an iliofemoral approach. Two other factors that make it more likely to require a total hip prosthesis are the extent of postoperative mismatch in the acetabular roof and non-anatomical reduction. If all poor prognostic factors are present, developing arthrosis and needing a total joint prosthesis is very likely. In this situation it is important to think very carefully and discuss this openly with the patient to make a decision together as to whether revision osteosynthesis should be undertaken or not.

3. Revision osteosynthesis

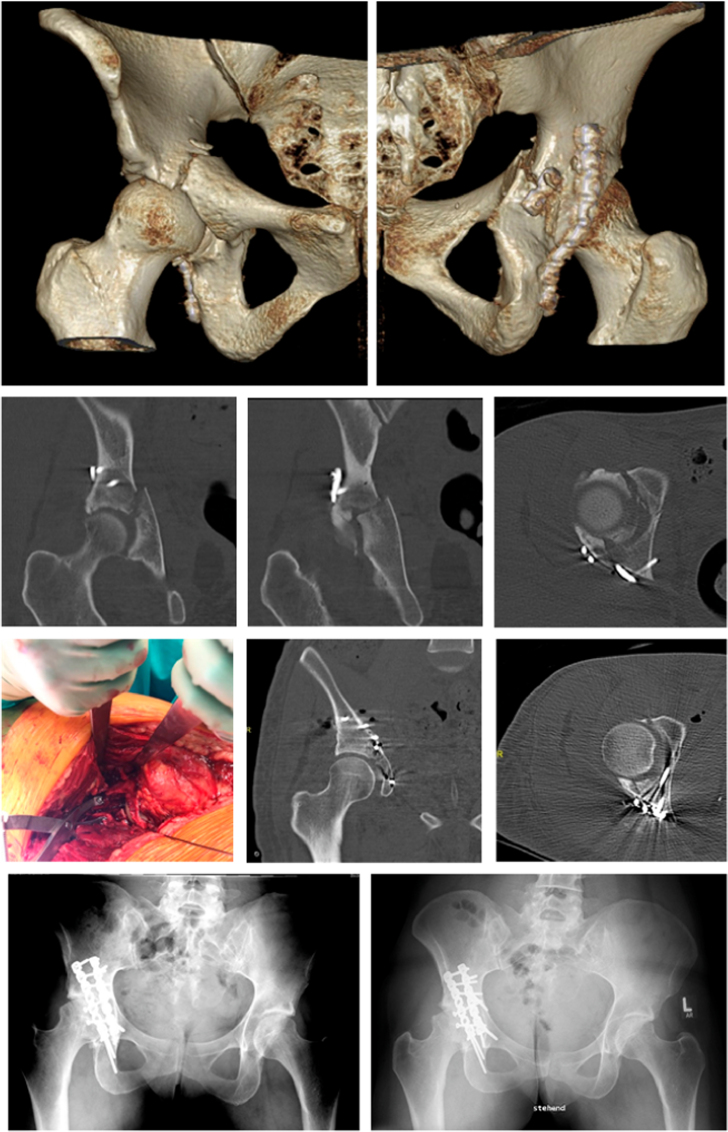

There are a number of problems identified during reoperation that can lead to increased technical difficulties.14 These include contracted scarred tissue and heterotopic ossification which can occur even if, for example, a different approach was chosen. In addition, increased blood loss can result from the resection of the scar tissue and the granulation tissue. The decision for reosteosynthesis depends on a variety of factors, as described above. Fig. 1 shows a case of a simple transverse posterior wall fracture in a 30-year-old patient who underwent surgical fixation in a peripheral unit and was transferred for revision fixation as the fracture had not been reduced anatomically via a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. During revision surgery, the fracture was debrided and reduced again using the same approach. The sacrospinous ligament had to be released in order to mobilize the posterior column sufficiently enough to achieve anatomical reduction using the Jungbluth clamp.

Fig. 1.

3D reconstruction of a transverse fracture after surgical treatment via a Kocher Langenbeck approach. The 3D reconstruction, as well as the coronary and axial CT sections show the incomplete reduction of the fracture. Both columns are not reduced correctly. Revision throughout the same approach. The fracture can be anatomically reduced using the Jungbluth tong. The postoperative CT sections show no more step. Bottom left postoperative pelvic overview and follow-up after 3 years.

Fig. 2 shows a 25-year-old male after high speed road traffic collision with combined pelvic and acetabular injury classified as a transverse right acetabular fracture and APC left hemi pelvis injury. He is smoker of 30 cigarettes per day. 18 months post successful fixation the X-rays of the patient showing failure of both anterior and posterior column fixation with broken plate and screws. Axial and sagittal cuts through CT scan showing the non-union of transverse fracture line. Following revision surgery with revision anterior and posterior fixation and bone grafting of the right acetabular fracture the fracture united.

Fig. 2.

25-year-old male after high speed road traffic collision with combined pelvic and acetabular injury. Transverse right acetabular fracture and APC left hemi pelvis injury. Smoker of 30 cigarettes per day. Upper row AP, Iliac and Obturator oblique views of post-operative pelvic and acetabular fracture fixation. Middle row AP, Iliac and Obturator oblique views of patient 18 months post fixation showing failure of both anterior and posterior column fixation with broken plate and screws. Bottom row: axial cuts through CT scan showing non-union of transverse fracture line. AP pelvic radiograph 1-year post revision anterior and posterior fixation and bone grafting right acetabular fracture non-union showing united fracture.

4. Revision with implantation of a hip prosthesis

If revision surgery does not allow significant improvement in reduction of the joint, or the damage to the cartilage is far worse than initially expected, it may be more appropriate to perform a complex primary total hip arthroplasty. Few studies have investigated the outcome of total hip arthroplasty after failed osteosynthesis or post-traumatic arthrosis. Schnaser et al.6 described a series of patients with acetabular fracture who were treated with a total endoprosthesis in a single facility after failed osteosynthesis. They compared functional results with patients treated with a primary hip prosthesis due to degenerative arthrosis. The results of total hip arthroplasty in patients with previously surgically treated acetabular fractures was worse than patients with a standard primary total hip replacement. There are risk factors for early revision even with good osteosynthesis.15 These include, for example, hip dislocations, significant cartilage damage and head or neck injuries to the femur. The extent of the destruction of the joint surface can prevent good reduction, stable fixation and joint congruence of the acetabulum. Pronounced dislocations that cause cartilage damage and impaction on the joint surface of the acetabulum can further complicate joint reconstruction. In addition, dislocation can disrupt the vascular supply of the femoral head and lead to avascular necrosis and subsequent joint collapse, even with early reduction and ideal osteosynthesis.16

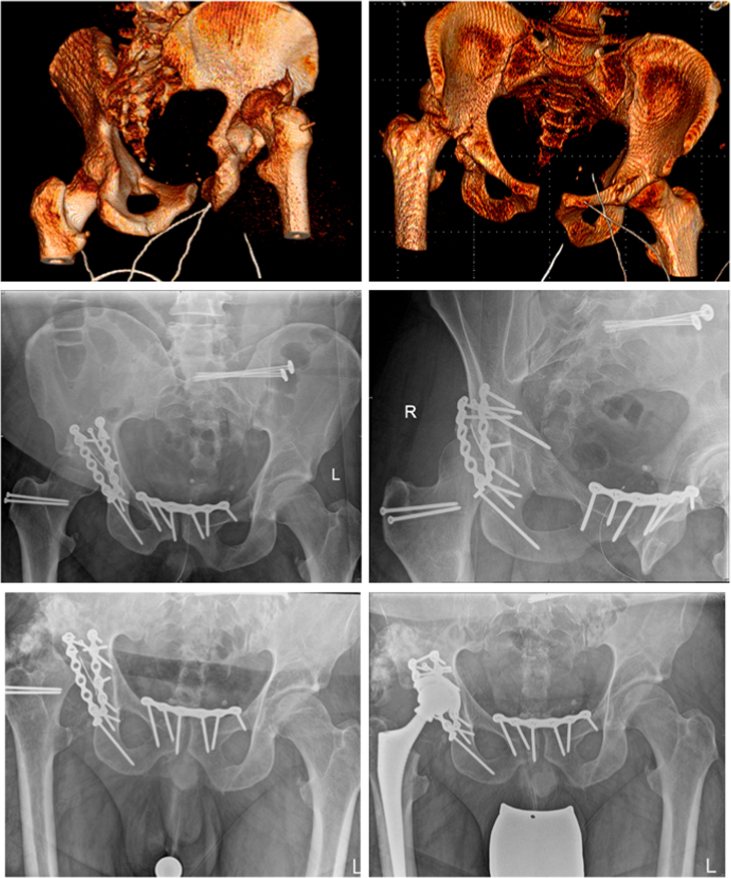

Fig. 3 shows 38-year-old patient who is very overweight 172 kg and is 190 cm tall. He suffered a hip dislocation with a simultaneous pelvic ring injury in a car accident. After primary stabilization with symphysis plating and iliosacral screw fixation, the acetabular fracture could be addressed 5 weeks after the trauma due to severe lung contusion. Despite the reasonably acceptable reconstruction, the patient developed marked heterotopic ossification and necrosis of the femoral head in due course. Therefore, a hip prosthesis had to be implanted. Stibold et al.17 examined the outcome of hip prostheses in a review. They showed that it can be more difficult to implant a total hip prosthesis where there has been a previous acetabular fracture and that it can be associated with relatively high complication rates. However, complex surgery in this group of patients can result in a significant improvement in pain and function at 10 years. It is important to note that the outcome in this group is still worse than with primary hip arthroplasty for arthrosis.

Fig. 3.

38-year-old patient (BMI 47) with hip dislocation and pelvic ring injury. Due to severe lung contusion the hip joint fracture could only be reconstructed 5 weeks after the trauma due to the severe lung contusion. Despite the acceptable reconstruction, the patient developed massive ossification and necrosis of the femoral head in the further course. Therefore, a hip prosthesis then had to be implanted.

5. Outcome after revision surgery

Overall, there is little literature on revision after failed osteosynthesis in acetabular surgery. In our own experience, these procedures are technically demanding, especially when it comes to performing reosteosynthesis in young patients. Nevertheless, it is a worthwhile consideration, especially when the primary reconstruction may imply that a poor outcome is likely and inevitable to lead osteoarthritis or non-union. Femoral head necrosis or heterotopic ossification can also occur, which may make a prosthesis necessary in the future. The largest series was published in 1994 by Keith Mayo together with Emile Letournel, Joel Matta, Jeffrey Mast, Eric Johnson and Claude L. Martiinbeau.14 In a total of 5 centers, they revised 64 patients over several years after failed osteosynthesis. The study evaluates the success of reoperation in 64 patients with poor reduction or secondary reduction loss. In 36 patients (56%), a reconstruction with defects or steps less than 2 mm could be achieved on conventional X-ray image. A total of 27 patients (42%) had excellent or good results with an average follow-up of 4.2 years. The delay in the reoperation adversely affected the outcome of the operation. At follow-up, 57% of patients who underwent surgery 3 weeks after the injury were rated good or excellent. This number dropped to 29% if the reoperation was not performed within 3 months. This data cannot be compared with the results of primary reconstructions. However, it is possible to salvage a significant number of failed osteosyntheses by reoperation. This study was based on a retrospective analysis of patient records and X-rays. The average follow-up time was 4.2 years (range 1.5–17 years). These data all were obtained during a time when CT imaging was not routinely performed in the postoperative period. Today, the number of revisions is reduced again by improved surgical techniques,2 better instruments18 and intraoperative 3D imaging. The routine use of C-arm fluoroscopy with the possibility of intraoperative 3D imaging of the reconstruction makes it possible to better assess the quality of the reduction and the position of implants. Necessary changes and corrections to the quality of reduction and implant position can be made intraoperatively if any malreductions or malpositions of implants is seen on intra operative 3D imaging. In our experience, about half of the patients who undergo reosteosynthesis benefit significantly and have a good outcome. The remaining patients end up with osteoarthritis and a secondary prosthesis. The time factor plays a crucial role in this patient group. If the problem of a non-anatomical reconstruction is recognized early on post-operative X-rays and CT scan, the consequences should be quickly drawn and the problem discussed with the patient. If the decision has been made to perform revision surgery to salvage the joint an expeditious work up to rule out infection and correct any ongoing physiological disturbance needs to be completed. The earlier the reoperation can be performed by experienced acetabular surgeons, the better the outcome after revision.

6. Conclusion

The operative care of acetabular fractures is technically demanding14 and should be carried out in centers that have sufficient experience with such operations and carry them out regularly. If the osteosynthesis fails, contemplating revision surgery may be necessary and can be extremely challenging due to scarring and ossification. In older patients, it is important to decide whether implanting a hip prosthesis is likely to give a better more predictable outcome. However, this surgery can be challenging also due to the scar tissue, bone stock and retained hardware not to mention any existing deformities. In younger patients, every attempt should be made to avoid a prosthesis. The decision to revise a fixation should be made in conjunction with the patient after outlining all the pros and cons of revision acetabular fracture fixation. The aim must be to perform revision surgery as soon as possible and to achieve anatomical reconstruction.

References

- 1.Routt M.L.C., Jr., Gary J.L., Kellam J.F., Burgess A.R. Improved intraoperative fluoroscopy for pelvic and acetabular surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;2(33 Suppl):S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001403. S37-S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gras F., Marintschev I., Grossterlinden L. The anterior intrapelvic approach for acetabular fractures using approach-specific instruments and an anatomical-preshaped 3-dimensional suprapectineal plate. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31:e210–e216. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letournel E. Acetabulum fractures: classification and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980:81–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Toole R.V., Hui E., Chandra A., Nascone J.W. How often does open reduction and internal fixation of geriatric acetabular fractures lead to hip arthroplasty? J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:148–153. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31829c739a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennal G.F., Davidson J., Garside H., Plewes J. Results of treatment of acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnaser E., Scarcella N.R., Vallier H.A. Acetabular fractures converted to total hip arthroplasties in the elderly: how does function compare to primary total hip arthroplasty? J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:694–699. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elnahal W.A., Ward A.J., Acharya M.R., Chesser T.J.S. Does routine postoperative computerized tomography after acetabular fracture fixation affect management? J Orthop Trauma. 2019;2(33 Suppl):S43–S48. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001405. S43-S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Archdeacon M.T., Dailey S.K. Efficacy of routine postoperative CT scan after open reduction and internal fixation of the acetabulum. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:354–358. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firoozabadi R., Alton T., Sagi H.C. Heterotopic ossification in acetabular fracture surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:117–124. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin S.M., Sims S.H., Karunakar M.A., Seymour R., Haines N. Heterotopic ossification rates after acetabular fracture surgery are unchanged without indomethacin prophylaxis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:2776–2782. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann W., Hoffmann M., Fensky F. What is the frequency of nerve injuries associated with acetabular fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3395–3403. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3838-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moed B.R., McMahon M.J., Armbrecht E.S. The acetabular fracture prognostic nomogram: does it work for fractures of the posterior wall? J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30:208–212. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tannast M., Najibi S., Matta J.M. Two to twenty-year survivorship of the hip in 810 patients with operatively treated acetabular fractures. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2012;94:1559–1567. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayo K.A., Letournel E., Matta J.M., Mast J.W., Johnson E.E., Martimbeau C.L. Surgical revision of malreduced acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;47–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding A., O’Toole R.V., Castillo R. Risk factors for early reoperation after operative treatment of acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32:e251–e257. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meena U.K., Tripathy S.K., Sen R.K., Aggarwal S., Behera P. Predictors of postoperative outcome for acetabular fractures. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stibolt R.D., Jr., Patel H.A., Huntley S.R., Lehtonen E.J., Shah A.B., Naranje S.M. Total hip arthroplasty for posttraumatic osteoarthritis following acetabular fracture: a systematic review of characteristics, outcomes, and complications. Chin J Traumatol. 2018;21:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmann W., Rueger J.M., Nuechtern J., Grossterlinden L., Kammal M., Hoffmann M. A novel electromagnetic navigation tool for acetabular surgery. Injury. 2015;46(Suppl 4):S71–S74. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383:-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]