Abstract

Aim and objective:

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the prevalence, burden and epidemiology of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). This systemic review was also aimed to highlight the challenges in the diagnosis and management of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in India (for all age groups). We also examined the published literature on the available treatment options and the role of prevention in the management of MRSA in India. By summarizing the currently available data, our objectives were to highlight the need for the prevention of MRSA infections and also emphasize the role of vaccination in the prevention of MRSA infections in India.

Methodology:

Electronic databases such as PubMed and databases of the National Institute of Science Communication and Information Resources and Indian Council of Medical Research Embase were searched for relevant literature published from 2005/01/01 to 2020/05/13 in English language, according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A manual search was also conducted using the key term “MRSA ‘or’ Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ‘and’ India.” An independent reviewer extracted data from the studies using a structured Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, and a meta-analysis of proportion for MRSA prevalence with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for all included individual studies were performed.

Result:

A total of 34 studies involving 16 237 patients were included in the final meta-analysis. The pooled proportion of patients with MRSA infection was 26.8% (95% CI: 23.2%-30.7%). The MRSA infection was more prevalent among male patients (60.4%; 95% CI: 53.9%-66.5%) as compared to female patients (39.6%; 95% CI: 33.5%-46.1%), while the prevalence of MRSA was higher among adults (18 years and above; 32%; 95% CI: 5%-80%) in comparison to pediatric patients (0-18 years; 68%; 95% CI: 20%-94.8%). The degree of heterogeneity was found to be significant.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of MRSA in India was relatively high at 27% with a higher proportion observed among men aged >18 years. The high prevalence of MRSA infections in India necessitates the implementation of surveillance and preventive measures to combat the spread of MRSA in both hospital and community settings.

Keywords: Methicillin resistant S. aureus, India, prevalence

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is a serious global health concern that limits the prevention and treatment of infections, especially in a hospital setting. Antimicrobial resistance develops by the inactivation of the antibiotic, altered drug access to the target, modification of target, and decreased uptake.1

As early as 1942, penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains were recognized, which further paved way to the development of semisynthetic penicillins, including methicillin.2 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the most tenacious anti-microbial resistant pathogens reported in a range of infections, including the skin and wound infections, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections.3,4 The emergence of MRSA through the acquisition of Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) was first identified in 1960.2,5 The SCCmec carries the mecA gene that encodes the penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a), thereby acquiring resistance to all β-lactam antibiotics.5 Newer drug-resistant homologues of the mecA gene have been reported in the recent years, including mecB, mecC, and/or mecD.6

The antimicrobial resistance patterns differ geographically, and the Asia-Pacific region accounts for one-third of the world’s population reporting a steadily increasing incidence of MRSA in healthcare settings since the 1980s.7 Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infection is an emerging infection in the Indian subcontinent with incidence rates of 25% to 50% reported in different parts of the country.8 According to the multicenter report of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)—Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance network presented in 2015, the prevalence of MRSA was reported in the range of 21% to 45% across the centres (Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research [JIPMER], Puducherry; India Institute of Medical Sciences [AIIMS], New Delhi; Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research [PGIMER], Chandigarh and Christian Medical College [CMC], Vellore), with an overall prevalence of 37.3%. This study also reported a high prevalence of resistance against commonly prescribed antimicrobials including ciprofloxacin (95%) and erythromycin (91%).9

The increasing trend of good clinical practices in hospitals has brought down the incidence of hospital-acquired MRSA infections; however, there is a steady increase in community-acquired MRSA infections, which poses challenges, particularly in densely populated countries like India. Further, the economic burden associated with the cost of treatment, long-term hospitalization, and the psychological stress considerably impact the healthcare systems across all regions.10

Over the past few years, several studies have reported the prevalence of MRSA in different clinical settings within the Indian subcontinent, but the results are inconsistent with limited sample sizes.8,11-13 Furthermore, few studies from the country suggest an impact of age and gender on MRSA carriage.14,15 It is imperative to understand the prevalence of risk factors, such as age and gender, on MRSA colonization at the country level to facilitate the implementation of appropriate infection control measures. This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the prevalence, burden and epidemiology of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). This systemic review was also aimed to highlight the challenges in the diagnosis and management of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in India (for all age groups). We also examined the published literature on the available treatment options and the role of prevention in the management of MRSA in India. By summarizing the currently available data, our objectives were to highlight the need for the prevention of MRSA infections and also emphasize the role of vaccination in the prevention of MRSA infections in India.

Methodology

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Recording Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA).

Eligibility criteria for studies

All human studies, published from 2005/01/01 to 2020/05/13 in English language that evaluated Indian patients of all age groups with a confirmed diagnosis of MRSA, were eligible for inclusion. We have also considered studies focusing on the Indian subcontinent, in particular or as one of the study sites.

Exclusion criteria for studies

All studies on MRSA patients that were conducted outside India or/and not conducted in the Indian population were excluded from the analysis. In addition, case studies, review articles, or studies for which full text was not available were excluded.

Measurements

The primary outcome of this study was the proportion of patients with MRSA in India. The secondary outcome was to determine the proportion of patients with MRSA across different age groups and gender from an Indian perspective.

Search strategy

We performed a systematic search on PubMed, using the key terms “(((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ MRSA) ‘and’ Epidemiology) ‘and’ India,” “(((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ MRSA) ‘and’ burden) ‘and’ India,” “((((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (Mortality)) ‘and’ (Morbidity)) ‘and’ (India),” “(((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (Prevalence)) ‘and’ (india),” “(((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (incidences)) ‘and’ (India),” “((((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (treatment)) ‘and’ (drug therapy)) ‘and’ (India),” “(((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (challenges)) ‘and’ (India),” “(((Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (clinical Management)) ‘and’ (India),” “(((Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) ‘or’ (MRSA)) ‘and’ (complications)) ‘and’ (India).” The search was performed after applying constant filters based on these additional search criteria: Article Types—Classical Article, Clinical Study, Clinical Trial, Clinical Trial Protocol, Clinical Trial, Phase I, Clinical Trial, Phase II, Clinical Trial, Phase III, Clinical Trial, Phase IV, Comparative Study, Consensus Development Conference, Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluation Study, Government Document, Guideline, Historical Article, Meta-Analysis, Multicenter Study, Observational Study, Overall, Practice Guideline, Pragmatic Clinical Trial, Randomized Controlled Trial; Language—English; Publication Date—2005/01/01 to 2020/05/13; Species—Humans. Additional records were identified through other sources [the National Institute of Science Communication and Information Resources (NISCAIR), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), World Health Organization (WHO), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)] using the search terms: “Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus” OR “MRSA” AND “India.” Handsearching was also performed on Google Scholar using the same key terms.

Data extraction

Data was collected from all the primary studies using a structured sheet in Microsoft Excel. Any discrepancies arising while entering the data were sorted out by discussion among all the contributors. The study characteristics extracted included authors details, year of publication, title of study, place of study, and type of study. Patient parameters included the number of study participants and their mean age. Two reviewers were involved in data extraction. Any disagreements among reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

To determine the proportion of MRSA, a meta-analysis was performed of 95% confidence interval (CI). Besides, a meta-analysis using a random-effects method (DerSimonian and Laird method), the degree of heterogeneity (i)2 among the studies, was planned. The outcomes were presented as pooled estimates with 95% CI. The i2 test assessed variation in the outcome of all included studies with respect to the primary and secondary objectives. The meta-analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 software.

Results

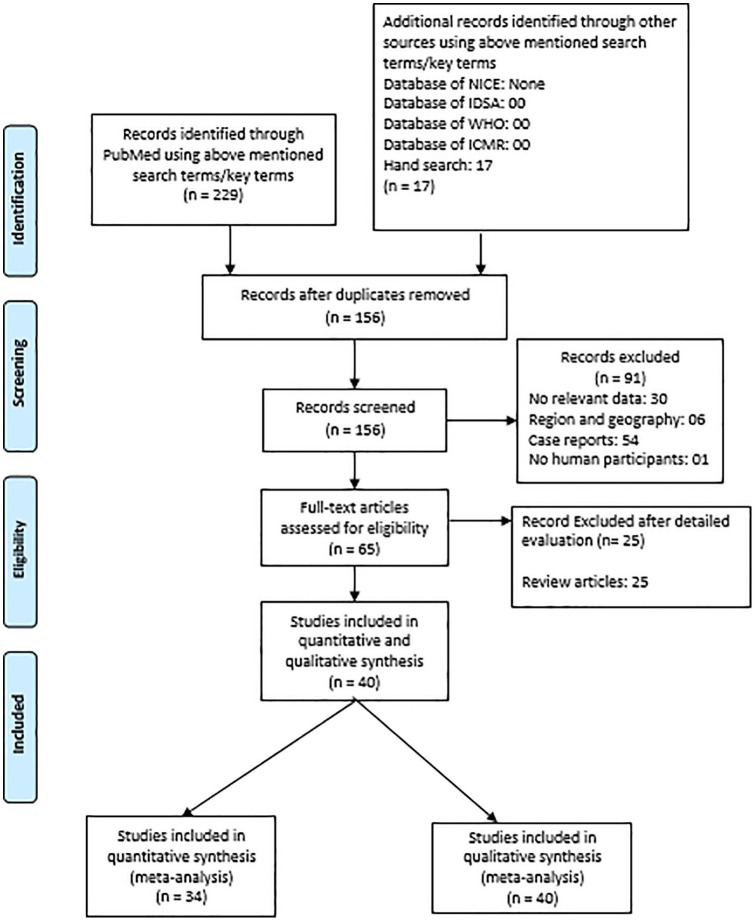

A total of 229 studies were retrieved via PubMed and Google Scholar search, while 17 studies were obtained by handsearching. No additional studies were retrieved via ICMR, IDSA, WHO, and NICE database search. Around 40 relevant studies (Figure 1) were identified. The exclusion criteria were: were duplicates (70), case reports (54), does not include relevant data (30), does not match region and geography (06), does not include human participants (1), and reviews (25). All of the 40 studies were considered for qualitative as well as the quantitative synthesis of etiological agents. Ultimately, only 34 of 40 studies were included in the MRSA meta-analysis,8,9,15-46 as the remaining 6 studies did not include data relevant to MRSA (4 efficacy studies, 1 study that described heteroresistance to vancomycin among methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates, and 1 survey wherein no exact data on prevalence were presented).47-52 Table 1 represents the characteristics of the studies included in the analysis. The studies included in the systematic literature review did not include randomized controlled trials so risk-bias analysis was not performed.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Abbreviations: ICMR, Indian Council of Medical Research; IDSA, infectious diseases society of America; WHO, World Health Organization; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Author | Design of the study/type of literature | Number of patients | Risk factor and etiology | Diagnostic test | Mean (±SD) /medium age (Range) in years | Study Objectives | Geographic location/type of hospital/province |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahubali et al16 | Retrospective study | 21 Patients | Postoperative/trauma, otogenic and hematogenous abscess, sinusitis, contiguous spread, immunosuppression (diabetes with pulmonary tuberculosis, malignant tumor, and leprosy) | Cerebral CT scan, MRI, triplex PCR assay | 31 (1 month-73 years) | To examine the prevalence, clinical and molecular characteristics, treatment options and outcome of MRSA intracranial abscess over a period of 6 years | India |

| Kumar et al17 | Retrospective study | 47 S. aureus isolate | VRSA, LRSA, TRSA | PCR amplification | Not available | To evaluate the resistance patterns of S. aureus collected over 2 years (December 2013-November 2015) from blood samples of patients admitted to 1 hospital | Odisha, East India |

| Kini et al18 | Retrospective observational study | 74 patients | Bone and joint infections, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, resistance of S. aureus to multiple antibiotics | Laboratory evaluations [including blood hemoglobin and hematocrit percentage, ESR, CRP, WBC, ANC, blood cultures positive for S. aureus, and radiographic studies (plain film, ultrasound evaluation, or MRI) | 8.76 for MRSA and 8.97 for MSSA (8 months to 17 years) | To compare invasive CA-MRSA and CA-MSSA bone and joint infections, characterize the spectrum and incidence of the disease, identify the presence or absence of traditional MRSA risk factors, determine antibiotic susceptibilities of these organisms, and predict a clinical algorithm that will help distinguish an MRSA infection | India |

| Rajaduraipandi et al19 | Multicenter study | 906 isolates | Resistance of S. aureus to multiple antibiotics, sensitivity to vancomycin and linezolid | Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method | Not available | To determine the prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of MRSA | Tamil Nadu |

| Noguchi et al20 | Prospective, multicountry study | 894 isolates | MRSA | PCR and PFGE typing | Not available | To examine the susceptibilities of MRSA to dyes and antiseptic agents | Asia |

| Mendem et al21 | Multicenter study | 387 clinical specimens | S. aureus, VRSA, inducible clindamycin resistance | D test, Mueller–Hinton agar plate, Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method | Not available | To evaluate the prevalence of antibiotic resistance among S. aureus species isolated from clinical samples from different locations in India | Delhi, Bengaluru, Palakkad, Chennai, and Gulbarga |

| Sakthirajan et al22 | Retrospective, observational study | 47 patients | Infection-related glomerulonephritis, rheumatic valvular disease, alcohol-related chronic liver disease, HIV infection, urinary tract infection, diarrhea, and pneumonia, ESRD, CKD, requirement of dialysis, hematuria, hypocomplementemia | Not available | 42 (± 13.5) years | To analyze the risk factors, etiology, clinical features, and outcome of crescentic infection-related glomerulonephritis. | Tamil Nadu |

| Kotpal et al23 | Case-control study | 100 patients | Hospitalization, intake of antibiotics, surgical procedure, tuberculosis, diabetes, alcohol intake, malignancy, smoking, corticosteroid intake, candidiasis, dermatitis, HIV infection, immunocompromised | Disk diffusion method, cefoxitin disk diffusion method | 33.96 for HIV-infected and 33.78 for HIV-uninfected individuals | To evaluate the prevalence of nasal colonization of S. aureus in individuals with HIV infection attending the Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre in a teaching hospital and compare the prevalence with that of HIV-uninfected individuals | India |

| Mehndiratta et al24 | Laboratory perspective study | 125 isolates | Not available | Agar screening method, PCR, PCR-RFLP | Not available | To characterize MRSA strains by molecular typing based on PCR-RFLP of spa gene and to assess the utility of spa genotyping over bacteriophage typing in the discrimination of the strains | Delhi |

| Gupta et al25 | Laboratory study | 200 Non-duplicate S. aureus isolate | Sensitivity to vancomycin and linezolid | Routine Kirby–Bauer disk Diffusion method | Not available | To determine the percentage of S. aureus having inducible clindamycin resistance using Dtest; to ascertain the association between MRSA and inducible clindamycin resistance as well as association of these isolates with community or nosocomial setting; to identify the treatment options for iMLS(B) isolates | Punjab |

| Batra et al26 | Retrospective observational study | 13 329 cultures | Blood cancer | Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method, HiCrome MeReSa agar | Not available | To study the epidemiology of microbiologically documented bacterial infection and the resistance pattern, among cancer patients undergoing treatment | Delhi |

| Rajkumar et al9 | ICMR antimicrobial resistance surveillance study | 8032 isolates | VRSA, skin and soft tissue infections, S. haemolyticus, S. epidermidis, S. caprae, S. cohnii, S. schleiferi, S. warneri, mupirocin resistance and S. lugdunensis | Kirby–Bauer disk‑diffusion method, PCR amplifications | Not available | To study antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus species as part of the Indian Council of Medical Research-AMR surveillance network | India |

| Mahapatra et al27 | Hospital-based study | 1017 specimens | Skin and soft tissue infection, septicemia, pneumonia, meningitis, none and joint space, clindamycin resistance | Not available | Not available | To evaluate antibiotic sensitivity and clinico-epidemiologic profile of Staphylococcal infections | Kolkata |

| Ravishankar et al28 | Cross-sectional, observational study | 73 patients | Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), hospitalization, surgery, dialysis, diabetes mellitus and HIV infections, resistant to clindamycin | Kirby–Bauer disk- diffusion method, cefoxitin disk diffusion test | 34.2 (10-69) years | To study the prevalence of MRSA in CA-SSTIs and to compare the socio-demographic and clinical profile of patients with SSTIs caused by MRSA and MSSA | Delhi |

| Thacker et al29 | Retrospective observational study | 4198 samples | Gram-negative Bacilli, BSI, coagulase-negative Staphylococci | Kirby–Bauer’s disk-diffusion method, cephalosporin–clavulanate combination disks | Not available | To describe the etiology and sensitivity of BSI in the pediatric oncology unit at a tertiary cancer center | Mumbai |

| Shah et al30 | Prospective observational study | 24 355 patients | E. coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, surgeries, SSIs | Not available | 51 (2 days-88 years) years | To generate accurate current data on rates, microbial etiology and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of SSIs | Mumbai, Maharashtra |

| Mandal et al31 | Hospital-based observational prospective study | 36 cases | Disseminated Staphylococcal disease, neutrophilic leucocytosis, bilateral pyopneumothorax, multiple pyemic abscesses with empyema, meningitis, pyopericardium, trauma, septic arthritis, skin infection | Complete hemogram, LFT, urea, creatinine, blood sugar, Candida skin test, ELISA, catalase test, slide coagulase test and tube coagulase test, Kirby–Bauer disk-diffusion method | 6.03 ± 3.04 (1-12) years | To assess the etiology, precipitating factors, treatment and outcome of DSD in healthy immuno-competent children | West Bengal |

| Mathews et al32 | Laboratory study | 610 isolates | Surgical-site wounds, diabetic foot infections, burns, osteomyelitis/septic arthritis, cellulitis, other skin infections, urinary tract infections, septicemia, pneumonia | Oxacillin disk diffusion, cefoxitin disk diffusion, oxacillin screen agar, PCR, agar diluti on method | Not available | To evaluate the efficacy of cefoxitin disk-diffusion test to detect MRSA and compare it with other phenotypic and molecular methods | Coimbatore, India |

| Rosenthal et al33 | Multicenter, prospective cohort surveillance study | 21 069 patients | Device-associated infections, VAP, laboratory-confirmed and clinically suspected central venous catheter-associated BSI, catheter-associated UTI, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, Acinetobacter, Enterobacteriaceae, Candida spp. | Not available | Not available | To ascertain the incidence of device-associated infections in the ICUs of developing countries | Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, India, Mexico, Morocco, Peru, and Turkey |

| Dube et al47 | Multicenter, open-label, randomized, comparative, parallel -group, active-controlled, phase III clinical trial | 162 patients | Postoperative wounds, pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections such as infected ulcers, and deep abscess, polymicrobial infections, serious infections like meningitis and endocarditis, CAP | Normal Rinne and Weber test | 40.80 (± 13.68) in arbekacin group and 40.65 (± 14.69) in vancomycin group | To evaluate the safety and efficacy of arbekacin sulfate injection versus vancomycin injection in patients diagnosed with MRSA infection | 9 centres in India |

| Umashankar et al48 | Open-label, prospective, placebo-controlled study | 372 patients | Pyoderma, Impetigo contagiosa, ecthyma, and folliculitis | Colony morphology, Gram stain, catalase test, slide and tube coagulase test and modified Hugh Leifson’s oxidation fermentation test, Kirby–Bauer disk-diffusion method | 12.31 in green tea group and 11.01 in placebo group (8 to 16) years | To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration of green tea against S. aureus and MRSA. | Karnataka, India |

| Corey et al50 | An international, randomized, double-blind study | 968 Patients | Acute wound infection, cellulitis, or major cutaneous abscess, diabetes mellitus, acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections | Not available | 46.2 (± 14.20) in oritavancin group and 44.3 (± 14.50) in vancomycin group (18-93 years) | To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a single dose of oritavancin as compared with a regimen of twice daily vancomycin for 7 to 10 days | Pune and Lucknow, India |

| Corey et al49 | Randomized, double-blind, clinical, trial | 1019 patients | Acute bacterial SSTIs, lipoglycopeptide, wound infection, cellulitis, abscess, diabetes mellitus | Not available | 45.0 (13.40) years in oritavancin group 44.4 (14.29) years in vancomycin group; range: 18-92 years | To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a single dose of oritavancin compared with a regimen of twice-daily vancomycin | One site is from Nagpur, India |

| Iyer et al51 | Laboratory study | 50 Isolates | Not available | Disk-diffusion method | Not available | To develop, standardize, and compare modified population analysis profile with the existing methodologies to detect hetero-resistance to vancomycin in MRSA isolates | Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh and Bengaluru, Karnataka |

| Asati et al34 | Hospital-based observational study | 860 admitted patient | Use of immunosuppressive agents, recent hospitalization, diabetes mellitus, smoking, sepsis, presence of cough, burning micturition, skin infection | Not available | 36.56 (± 23.76) years (1-90) years | To study the frequency, etiology, and outcome of sepsis dermatology inpatients | Delhi |

| Siddaiahgari et al35 | Prospective study | 89 isolates | Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Acinetobacter | Disk-diffusion method | Not available | To study the likely etiologic agents and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern among systemic infections in children with cancer | Telangana, India |

| Chatterjee et al8 | Cohort study1 | 551 subjects | MRSA, MSSA, SSTIs, deep abscess, abdominal sepsis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, respiratory tract infection | Kirby–Bauer disk-diffusion method, cefoxitin disk-diffusion method | 46.39 ± 16.08 in MRSA group and 44.77 ± 14.31 in MSSA group | To determine morbidity and mortality of MRSA and MSSA infections in a tertiary health-care facility | Manipal, South India |

| Eshwara et al36 | Prospective observational cohort study | 70 cases of S. aureus bacteremia | S. aureus, BSI, MRSA, SSTIs, respiratory infections, MSSA | Kirby–Bauer disk-diffusion method, cefoxitin disk diffusion | 44 (0-76) years | To analyze the epidemiology and laboratory characteristics of S. aureus bacteremia in an Indian tertiary care hospital | Southern India |

| Bouchiat et al37 | Prospective observational study | 92 S. aureus clinical isolates | S. aureus, MRSA, SSTIs, UTI, respiratory infection, bone and joint infection and sepsis, CA S. aureus infection | Disk-diffusion method, PCR | 43 years (range, 7 days-91 years) | To determine the antibiotic susceptibility pattern of S. aureus and the circulating clones | Bengaluru, India |

| Choudhury et al38 | Retrospective study | 724 positive Staphylococcus strains cases | MRSA, MSSA, | Not available | Not available | To determine the prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of MRSA | Assam, India |

| Rampal et al52 | Survey study | 264 critical care specialists | MRSA, acute bacterial SSSIs, CAP, VAP, CLABSI, and DFI | Not available | Not available | To determine the burden of Gram-positive infections in critical care settings and to understand the practising behavior among the specialists in the management of MRSA infections | India |

| Mehta et al39 | Surveillance study | 13 610 samples | MRSA, MSSA | Disk-diffusion method | Not available | To determine the incidence of MRSA in Indian hospitals and to compare the antimicrobial activity of currently available antibiotics | Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru |

| Abimannan et al40 | A cross‑sectional study | 769 isolates | CA MRSA, CA MSSA | Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method, disk approximation test, multiplex PCR; agr typing, spa typing, and multilocus sequence typing | Not available | To evaluate the molecular, epidemiologic, and virulence characteristics of S. aureus in both community and hospital settings | Tamil Nadu, India |

| Senthilkumar et al41 | Hospital-based study | 98 isolates | Exanthematous illness (fever with rash), history of minor trauma causing skin discontinuity, hospitalization, antibiotic usage, immunosuppressant usage, contact with potential S. aureus-infected patient | PCR, D test, | Not available | To identify the clinical variables that differentiate MRSA from MSSA infection | Pondicherry, India |

| Chamania et al42 | Retrospective review study | 102 patients | Extended duration of hospitalization, previous hospitalization, invasive procedures, comatose state, and advancing age | Not available | Not available | To analyze the incidence of multi drug-resistant organisms in burn patients and to co-relate sepsis-induced mortality with underlying MDR infection | Indore, India |

| Nagaraju et al43 | Prospective study (part of school camp) | 372 children | S. aureus carriage, pyoderma caused by S. aureus, ecthyma, immunocompetent patients, lifestyle changes (hygiene) and folliculitis | Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method | 5 to 16 years | To evaluate different types of primary pyoderma in children caused by S. aureus and to determine the incidence of MRSA in community‑acquired primary pyoderma in children | Bengaluru, South India |

| Singh et al15 | Prospective, cross‑sectional, and observational study | 300 school‑going children | Socioeconomic status, frequent medication with antibiotics, hospitalization, chronic disease, and previous infection with MRSA | Cefoxitin 30-μg disks and D‑zone test, Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion | 5 to 15 years | To determine the prevalence of nasal colonization of MRSA, the minimum inhibitory concentration of oxacillin and vancomycin, inducible clindamycin resistance, and antimicrobial resistance pattern of S. aureus | Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Indian Network for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Group44 | Retrospective study | 26 310 isolates | Not available | Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion technique | Not available | To determine the prevalence of MRSA and susceptibility pattern of S. aureus isolates in India | 15 Indian tertiary care centers across North, South, and West India |

| Kumar et al45 | Hospital-based study | 133 culture-positive S. aureus samples | Surgical wound infections, intake of antibiotics | Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method | Not available | To determine the prevalence of MRSA in surgical wound infections and also to define the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the strains isolated | North-eastern part of India |

| Basavaraj et al46 | Hospital-based study | 137 isolates | Excessive antibiotic usage, prolonged hospitalization, intravascular catheterization and hospitalization in an intensive care unit | Oxacillin disk-diffusion method, Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion | Not available | To provide data for empiric selection of appropriate antibiotics for the treatment of diseases caused by S. aureus | Karnataka, South India |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; VRSA, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus; LRSA, linezolid-resistant S. aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CA, community associated; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism; spa, Staphylococcus aureus protein A; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; CA-SSTIs, community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections; BSI, Bloodstream infection; SSIs, Surgical-site infections; LFT, liver function tests; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; DSD, disseminated staphylococcal disease; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; UTI, urinary tract infection; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; SSSI, skin and skin structure infections; CLABSI: central line-associated bloodstream infection; DFI, diabetic foot infections; TRSA, tigecycline-resistant S. aureus.

Primary outcome

The meta-analysis included 16 237 patients aged between 1 month to 93 years. Clinical diagnosis was made by polymerase chain reaction assay, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing, radiologic evaluations (computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging), laboratory evaluations, D test, Mueller–Hinton agar plate, antimicrobial discs methods like Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method, Candida skin test, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, catalase test, slide coagulase test, tube coagulase test, Normal Rinne and Weber test, colony morphology, and Gram’s stain. Majority of studies used antimicrobial disc methods such as Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method for clinical diagnosis of MRSA (Table 1).

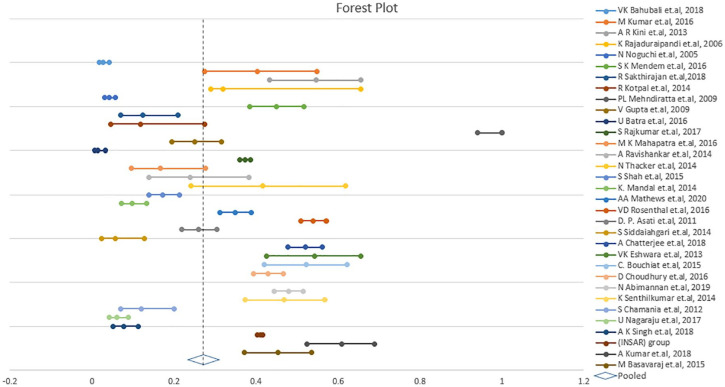

The pooled proportion of patients with MRSA infection was 26.8% (95% CI: 23.2%-30.7%; I2 = 97.69%; P < .001; Table 2, Figure 2). The degree of heterogeneity was significant.8,9,15-46

Table 2.

Proportion of MRSA infection in Indian patients.

| Study | Odds ratio/proportion of patients with MRSA | Lower CI | Upper CI | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahubali16 | 0.027 | 0.018 | 0.041 | 3.01 |

| Kumar et al17 | 0.404 | 0.275 | 0.549 | 2.68 |

| Kini et al18 | 0.547 | 0.434 | 0.655 | 2.97 |

| Rajaduraipandi et al19 | 0.319 | 0.289 | 0.655 | 3.49 |

| Noguchi et al20 | 0.042 | 0.031 | 0.057 | 3.23 |

| Mendem et al21 | 0.45 | 0.384 | 0.518 | 3.32 |

| Sakthirajan et al22 | 0.124 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 2.57 |

| Kotpal et al23 | 0.118 | 0.045 | 0.275 | 1.73 |

| Mehndiratta et al24 | 1 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.42 |

| Gupta et al25 | 0.25 | 0.195 | 0.315 | 3.24 |

| Batra et al26 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 2.03 |

| Rajkumar et al9 | 0.373 | 0.36 | 0.386 | 3.55 |

| Mahapatra et al27 | 0.167 | 0.095 | 0.276 | 2.53 |

| Ravishankar et al28 | 0.239 | 0.138 | 0.382 | 2.47 |

| Thacker et al29 | 0.417 | 0.241 | 0.617 | 2.18 |

| Shah et al30 | 0.173 | 0.139 | 0.214 | 3.34 |

| Mandal et al31 | 0.098 | 0.072 | 0.133 | 3.19 |

| Mathews et al32 | 0.349 | 0.312 | 0.388 | 3.47 |

| Rosenthal et al33 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.571 | 3.51 |

| Asati et al34 | 0.259 | 0.218 | 0.305 | 3.39 |

| Siddaiahgari et al35 | 0.056 | 0.024 | 0.128 | 1.99 |

| Chatterjee et al8 | 0.52 | 0.478 | 0.562 | 3.47 |

| Eshwara et al36 | 0.543 | 0.426 | 0.655 | 2.93 |

| Bouchiat et al37 | 0.522 | 0.42 | 0.622 | 3.06 |

| Choudhury et al38 | 0.43 | 0.394 | 0.466 | 3.49 |

| Mehta et al39 | 0.318 | 0.285 | 0.352 | 3.48 |

| Abimannan et al40 | 0.48 | 0.445 | 0.515 | 3.49 |

| Senthilkumar et al41 | 0.469 | 0.373 | 0.568 | 3.09 |

| Chamania et al42 | 0.12 | 0.069 | 0.2 | 2.63 |

| Nagaraju et al43 | 0.061 | 0.041 | 0.089 | 3.06 |

| Singh et al15 | 0.077 | 0.051 | 0.113 | 3.03 |

| (INSAR) Group44 | 0.41 | 0.404 | 0.416 | 3.56 |

| Kumar et al45 | 0.609 | 0.524 | 0.688 | 3.19 |

| Basavaraj et al46 | 0.453 | 0.371 | 0.536 | 3.21 |

| Pooled proportion | 0.268 | 0.232 | 0.307 |

Abbreviations: MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Forest plot displaying meta-analysis of proportion of prevalence in MRSA. Binary random effects model was applied to get pooled proportion and 95% confidence interval (0.268; 95% CI 0.232-0.307; P < .001).

Secondary outcome

According to the subgroup analysis, the prevalence of MRSA infection was more in males [60.4%; 95% CI 53.9%-66.5%] than in female [39.6%; 95% CI 33.5%-46.1%] (Table 3) while prevalence was more in adult (18 years and above; 68%; 95% CI 20%-94.8%) in comparison with pediatric patients (0-18 years; 32%; 95% CI 5%-80%) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Prevalence of MRSA in males and females.

| Author and Year | Number of male Subjects with MRSA | Number of female Subjects with MRSA | Total number of subjects with MRSA | Proportion | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahubali et al16 | 18 | – | 21 | 0.857 | 0.637 | 0.97 |

| Kini et al18 | 27 | – | 41 | 0.659 | 0.494 | 0.799 |

| Ravishankar et al28 | 4 | – | 11 | 0.364 | 0.109 | 0.692 |

| Rosenthal et al33 | 312 | – | 548 | 0.569 | 0.527 | 0.611 |

| Choudhury et al38 | 183 | – | 311 | 0.588 | 0.531 | 0.643 |

| Singh et al15 | 16 | – | 23 | 0.696 | 0.471 | 0.868 |

| Summary | 0.604 | 0.539 | 0.665 | |||

| Bahubali et al16 | – | 3 | 21 | 0.143 | 0.030 | 0.363 |

| Kini et al18 | – | 14 | 41 | 0.341 | 0.201 | 0.506 |

| Ravishankar et al28 | – | 7 | 11 | 0.636 | 0.063 | 0.891 |

| Rosenthal et al33 | – | 236 | 548 | 0.431 | 0.389 | 0.473 |

| Choudhury et al38 | – | 128 | 311 | 0.412 | 0.356 | 0.469 |

| Singh et al15 | – | 7 | 23 | 0.304 | 0.132 | 0.529 |

| Summary | 0.396 | 0.335 | 0.461 | |||

Table 4.

Prevalence of MRSA in adult and pediatric patients.

| Author | Number of pediatric subjects (0-18 years) with MRSA | Number of adult subjects (18 years and above) with MRSA | Total number of subjects with MRSA | Proportion | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kini et al18 | 41 | – | 41 | 0.988 | 0.836 | 0.999 |

| Sakthirajan et al22 | 0 | – | 47 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.146 |

| Mahapatra et al27 | 11 | – | 11 | 0.958 | 0.575 | 0.997 |

| Ravishankar et al28 | 0 | – | 11 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.425 |

| Mandal et al31 | 36 | – | 36 | 0.986 | 0.818 | 0.999 |

| Dube et al47 | 0 | – | 162 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.047 |

| Umashankar et al48 | 24 | – | 24 | 0.980 | 0.749 | 0.999 |

| Corey et al49 | 0 | – | 204 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.038 |

| Corey et al50 | 0 | – | 201 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.038 |

| Chatterjee et al8 | 0 | – | 284 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.027 |

| Eshwara et al36 | 8 | – | 38 | 0.211 | 0.109 | 0.368 |

| Nagaraju et al43 | 24 | – | 24 | 0.980 | 0.749 | 0.999 |

| Singh et al15 | 23 | – | 23 | 0.979 | 0.741 | 0.999 |

| Summary | 0.320 | 0.052 | 0.8 | |||

| Kini et al18 | – | 0 | 41 | 0.012 | 0.001 | 0.164 |

| Sakthirajan et al22 | – | 47 | 47 | 0.990 | 0.854 | 0.999 |

| Mahapatra et al27 | – | 0 | 11 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.425 |

| Ravishankar et al28 | – | 11 | 11 | 0.958 | 0.575 | 0.997 |

| Mandal et al31 | – | 0 | 36 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.182 |

| Dube et al47 | – | 162 | 162 | 0.997 | 0.953 | 1.000 |

| Umashankar et al48 | – | 0 | 24 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.251 |

| Corey et al49 | – | 204 | 204 | 0.998 | 0.962 | 1.000 |

| Corey et al50 | – | 201 | 201 | 0.998 | 0.962 | 1.000 |

| Chatterjee et al8 | – | 284 | 284 | 0.998 | 0.973 | 1.000 |

| Eshwara et al36 | – | 30 | 38 | 0.789 | 0.632 | 0.891 |

| Nagaraju et al43 | – | 0 | 24 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.251 |

| Singh et al15 | – | 0 | 23 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.259 |

| Summary | 0.680 | 0.200 | 0.948 | |||

A total of 10 studies8,16,18,23,28,31,36,38,41,46 identified risk factors and co-morbidities, including diabetes, tuberculosis, malignancy, leprosy, extremes of age, group-house inhabitants, high mean body temperature (101.80°F), history of preceding illness/upper respiratory tract infections/trauma, abnormal laboratory values (hemoglobin [<9.5 g%], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [>35 mm/h], c-reactive protein [>32 mg/dL], leucocytes (>14 000 cells/109 L), absolute neutrophil count [(>65%]), immuno-compromised status, hospitalization in the last 3 months, present intake/history of antibiotics, history of surgical procedures, history of alcohol intake and smoking, history of intravenous drugs, history of corticosteroid intake, history of mucocutaneous candidiasis, history of dermatitis, history of sexually transmitted infections, socio-economic status, chronic kidney disease, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, MRSA carriage (nasal or axillary or perineal or hand carriage in patients), prolonged duration of hospital stay, and irrational use/over prescription of antibiotics.

Four studies conducted in India focusing on the treatment of MRSA infections were identified; Arbekacin sulfate (200 mg) has shown 79% cure rate47 and vancomycin hydrochloride (1000 mg BD) has shown a curate rate of 100% cure rate,47 78.90%,49 and 82.9%50 in 3 studies, respectively. Besides, 2 studies suggested oritavancin as one of the treatment options for MRSA infections, with a cure rate of 82.30%49 and 80.1%, respectively.50

The survey conducted by Rampal et al, indicated an increasing trend in the prevalence and associated mortality in Gram-positive bacterial infections in critical care settings in India.52 The limitations of the existing anti-MRSA agents necessitate the development of a newer agent with a broad spectrum anti-bacterial activity along with an improved safety profile.

Discussion

In order to reduce the burden of MRSA infections, continuous efforts should be made to prevent the spread and emergence of resistance by early detection of the resistant strains and using proper infection control measures in the hospital setting.17 As most S. aureus strains are resistant to multiple antibiotics, treatment of S. aureus infections may have resulting complications. Hence, less interest is shown toward the development of new antibiotics. Other reasons include high cost and limited success rate. In such cases, vaccination might be beneficial to high-risk patients (such as dialysis patients, patients at risk of endocarditis, patients undergoing surgery, sports persons, prison inmates, and health-care workers who are the potential sources of dissemination of hospital-associated MRSA). Therefore, many researchers focus on developing vaccines and therapeutic antibodies, rather than novel antibiotics, as the process is comparatively easy and inexpensive.17 The IDSA recommended the expansion of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funding of both innate and adaptive immune strategies to prevent and treat antimicrobial-resistant infections. The strategies include active vaccination, passive immunization with polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies, and other immune-enhancing therapies.53

In recent years, increasing prevalence of hospital-acquired and community-acquired MRSA infections have been reported in Indian population.40,43 This meta-analysis is the first to report the recent prevalence estimates and burden of MRSA among the Indian population. We also identified the high-risk groups in terms of age and gender so as to improve the disease surveillance and interventions of MRSA.

The pooled prevalence of MRSA in our study was 26.8%. These findings are almost similar to the estimates from other regions. The meta-analysis study by Wong et al has reported an MRSA prevalence of 0% to 23% in community settings and 0.7% to 10.4% in hospital settings in the Asia-Pacific region. Further, the study also reported a higher prevalence of community-acquired MRSA in India (16.5%-23.5%), followed by Vietnam (7.9%) and Taiwan (3.5%-3.8%).54 A meta-analysis conducted by Wu and colleagues had reported an MRSA prevalence rate of 21.2% (95% CI, 18.5%-23.9%) in the healthy Chinese population.2 Further, the reported prevalence of MRSA in Ethiopia, was 30.90% [95% CI, 21.81%-39.99%], while in Europe and the United States the prevalence rate was only 1.8% (95% CI, 1.34%-2.50%).55,56

The subgroup analysis reported a higher prevalence of MRSA among males compared to females in the Indian population (60.4% vs 39.6%), thereby indicating male gender to be a risk factor for MRSA infections. Similar to our findings, multivariate analysis by Harbath and colleagues reported male gender as 1 of the 9 independent risk factors of MRSA with an odds ratio of 1.9 (1.3-2.7).57 In addition, a long-term study, spanning 7 years, conducted by Kupfer et al suggested male gender as a significant risk factor for MRSA acquisition.58 Behavioral and physiological factors contribute to the high occurrence of MRSA in male population. Behavioral practices that may potentially influence MRSA colonization and infection rates in males include personal hygiene issues (including hand hygiene and nose picking and nail-biting habit), profession (those working with livestock industry), and playing contact sports. The physiological and immunological factors increasing the MRSA prevalence in males include an aggressive inflammatory immune response and higher levels of circulating inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α.14 Limited data on the association of higher gender differences and MRSA necessitate further research on the association between gender dimorphism and higher MRSA carriage in males.

Findings from our analysis indicate a higher prevalence of MRSA among adults (>18 years) compared to the pediatric population including adolescents (68% vs 32%).59 An increased prevalence of MRSA in the adult population is associated with age-related changes including malnutrition and anatomic and physiologic modifications along with immune system dysfunction. Another meta-analysis by Lim et al studying the prevalence of MRSA in the Asia-Pacific region has reported a higher MRSA carriage prevalence among adults compared to children below 18 years of age. Similarly, a study by Wu et al had reported younger age as an influencing factor for MRSA colonization in healthy Chinese population.2 The existing literature on the differences in MRSA carriage among different age groups is inconsistent because of the differences in the population included in such studies. Further studies are needed to assess the prevalence of MRSA across different age groups within similar cohorts.

The differences in prevalence across different geographic regions may be attributed to the methodologic variations of isolation and detection of MRSA, study population included for analysis, availability of health-care services, and the economic level of the assessed regions.

In our analysis, we also identified the treatment options for MRSA. Findings from the 4 studies included in our analysis suggest arbekacin sulfate of 200 mg, vancomycin hydrochloride of 100 mg, and oritavancin as the treatment options for MRSA infections in India.47,49,50 Various clinical studies and systematic reviews have reported beneficial clinical outcomes with these antibiotics in the treatment of MRSA infections.60-62

The strengths of our meta-analysis is inclusion of a larger number of studies having a sufficiently large sample size. Further, as MRSA infections are a serious public health concern, this meta-analysis, the first to be conducted in the Indian population, may provide epidemiologic data on MRSA and the associated risk factors.

Our study has a few limitations in terms of inclusion of studies that had heterogeneity in the prevalence of MRSA and wide variation in patient cohorts. Further prospective studies are required to verify these results in order to facilitate preventive measures for mitigating MRSA in the Indian subcontinent.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis documents the prevalence of MRSA in India, which is considerably higher than that reported in other Asian countries. Further, the increased prevalence of MRSA in male patients of age >18 years highlights the need for further examination in these high-risk cohorts. Appropriate surveillance and preventive measures for reducing the risk of development and transmission of MRSA in the Indian subcontinent are indispensable.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This metaanalysis was funded by Pfizer Limited, India.

Author Contributions: CJG was involved in the design of meta-analysis, did the data analyses, and wrote the first draft of this manuscript with input from SW who assisted with the tables and figures and GR who also advised on the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to refining their approved submitted manuscript.

ORCID iD: Canna Jagdish Ghia  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9839-3209

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9839-3209

References

- 1. Yu H, Wang Y, Wang X, et al. Jatrorrhizine suppresses the antimicrobial resistance of methicillin‑resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Exp Ther Med. Published online September 23, 2019. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.8034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu M, Tong X, Liu S, Wang D, Wang L, Fan H. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy Chinese population: a system review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0223599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arjyal C, Kc J, Neupane S. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in shrines. Int J Microbiol. 2020;2020:7981648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhen X, Lundborg CS, Zhang M, et al. Clinical and economic impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a multicentre study in China. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sit PS, Teh CSJ, Idris N, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection and the molecular characteristics of MRSA bacteraemia over a two-year period in a Tertiary Teaching Hospital in Malaysia. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lakhundi S, Zhang K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31:e00020-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lim WW, Wu P, Bond HS, et al. Determinants of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;16:17-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatterjee A, Rai S, Guddattu V, Mukhopadhyay C, Saravu K. Is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus infection associated with higher mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients? A cohort study of 551 patients from South Western India. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:243-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rajkumar S, Sistla S, Manoharan M, et al. Prevalence and genetic mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus species: a multicentre report of the indian council of medical research antimicrobial resistance surveillance network. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2017;35:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prabhoo R, Chaddha R, Iyer R, Mehra A, Ahdal J, Jain R. Overview of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus mediated bone and joint infections in India. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2019;11:8070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mehta Y, Hegde A, Pande R, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care unit setting of India: a review of clinical burden, patterns of prevalence, preventive measures, and future strategies. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:55-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chacko J, Kuruvila M, Bhat G. Factors affecting the nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agarwala S, Lad D, Agashe V, Sobti A. Prevalence of MRSA colonization in an adult urban Indian population undergoing orthopaedic surgery. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2016;7:12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Humphreys H, Fitzpatick F, Harvey BJ. Gender differences in rates of carriage and bloodstream infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus : are they real, do they matter and why? Clin Infect Dis. Published online July 22, 2015. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh AK, Agarwal L, Kumar A, Sengupta C, Singh RP. Prevalence of nasal colonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among schoolchildren of Barabanki district, Uttar Pradesh, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:162-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bahubali VKH, Vijayan P, Bhandari V, Siddaiah N, Srinivas D. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus intracranial abscess: an analytical series and review on molecular, surgical and medical aspects. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2018;36:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kumar M. Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, India, 2013–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1666-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kini AR, Shetty V, Kumar AM, Shetty SM, Shetty A. Community-associated, methicillin-susceptible, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bone and joint infections in children: experience from India. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2013;22:158-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajaduraipandi K, Mani KR, Panneerselvam K, Mani M, Bhaskar M, Manikandan P. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus: a multicentre study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:34-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noguchi N, Suwa J, Narui K, et al. Susceptibilities to antiseptic agents and distribution of antiseptic-resistance genes qacA/B and smr of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Asia during 1998 and 1999. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:557-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mendem SK, Alasthimannahalli Gangadhara T, Shivannavar CT, Gaddad SM. Antibiotic resistance patterns of Staphylococcus aureus: a multi center study from India. Microb Pathog. 2016;98:167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakthirajan R, Dhanapriya J, Nagarajan M, Dineshkumar T, Balasubramaniyan T, Gopalakrishnan N. Crescentic infection related glomerulonephritis in adult and its outcome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29:623-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kotpal R, Prakash SK, Bhalla P, Dewan R, Kaur R. Incidence and risk factors of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in HIV-infected individuals in comparison to HIV-uninfected individuals: a case–control study. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2016;15:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mehndiratta PL, Bhalla P, Ahmed A, Sharma YD. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains by PCR-RFLP of SPA gene: a reference laboratory perspective. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gupta V, Datta P, Rani H, Chander J. Inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: a study from North India. J Postgrad Med. 2009;55:176-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Batra U, Goyal P, Jain P, et al. Epidemiology and resistance pattern of bacterial isolates among cancer patients in a Tertiary Care Oncology Centre in North India. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53:448-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahapatra MK, Mukherjee D, Poddar S, et al. Research letters. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:923-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ravishankar A, Singh S, Rai S, Sharma N, Gupta S, Thawani R. Socio-economic profile of patients with community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections in Delhi. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:279-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thacker N, Pereira N, Banavali S, et al. Epidemiology of blood stream infections in pediatric patients at a Tertiary Care Cancer Centre. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51:438-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah S, Singhal T, Naik R. A 4-year prospective study to determine the incidence and microbial etiology of surgical site infections at a private tertiary care hospital in Mumbai, India. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:59-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mandal K, Roy A, Sen S, Bag T, Kumar N, Moitra S. Disseminated staphylococcal disease in healthy children—experience from two tertiary care hospitals of West Bengal. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mathews AA, Thomas M, Appalaraju B, Jayalakshmi J. Evaluation and comparison of tests to detect methicillin resistant S. aureus. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenthal VD, Maki DG, Salomao R, et al. Device-associated nosocomial infections in 55 intensive care units of 8 developing countries. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:582-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asati DP, Sharma VK, Khandpur S, Khilnani GC, Kapil A. Clinical and bacteriological profile and outcome of sepsis in dermatology ward in tertiary care center in New Delhi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Siddaiahgari S, Manikyam A, Kumar KA, Rauthan A, Ayyar R. Spectrum of systemic bacterial infections during febrile neutropenia in pediatric oncology patients in tertiary care pediatric center. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51:403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eshwara VK, Munim F, Tellapragada C, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in an Indian tertiary care hospital: observational study on clinical epidemiology, resistance characteristics, and carriage of the Panton–Valentine leukocidin gene. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e1051-e1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bouchiat C, El-Zeenni N, Chakrakodi B, Nagaraj S, Arakere G, Etienne J. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in Bangalore, India: emergence of the ST217 clone and high rate of resistance to erythromycin and ciprofloxacin in the community. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;7:15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Choudhury D, Chakravarty P. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Silchar Medical College and Hospital, Assam, India. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;5:2174-2177. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mehta A, Rodrigues C, Kumar R, et al. A pilot programme of MRSA surveillance in India.(MRSA Surveillance Study Group). J Postgrad Med. 1996;42:1-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abimannan N, Sumathi G, Krishnarajasekhar OR, Sinha B, Krishnan P. Clonal clusters and virulence factors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: evidence for community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus infiltration into hospital settings in Chennai, South India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2019;37:326-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Senthilkumar K, Biswal N, Sistla S. Risk factors associated with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in children. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:31-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chamania S, Hemvani N, Joshi S. Burn wound infection: current problem and unmet needs. Indian J Burns. 2012;20:18-22. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nagaraju U, Raju BP. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community-acquired pyoderma in children in South India. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2017;18:14. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Indian Network for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Group, India. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in India: prevalence & susceptibility pattern. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:363-369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kumar A, Kumar A. Prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) in a secondary care hospital in north eastern part of India. Arch Infect Dis Ther. 2018;2:1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Basavaraj CM, Peerapur B, Jyothi P. Drug resistance patterns of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in tertiary care Center of South India. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7:70-72. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dube A, Deb AK, Das C, et al. A Multicentre, Open label, randomized, comparative, parallel group, active-controlled, phase III clinical trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of arbekacin sulphate injection versus vancomycin injection in patients diagnosed with MRSA infection. J Assoc Physicians India. 2018;66:47-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Umashankar N, Pemmanda B, Gopkumar P, Hemalatha AJ, Sundar PK, Prashanth HV. Effectiveness of topical green tea against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in cases of primary pyoderma: an open controlled trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Corey GR, Kabler H, Mehra P, et al. Single-dose oritavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2180-2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Corey GR, Good S, Jiang H, et al. Single-dose oritavancin versus 7–10 days of vancomycin in the treatment of gram-positive acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: the SOLO II noninferiority study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:254-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Iyer RN, Hittinahalli V. Modified PAP method to detect heteroresistance to vancomycin among methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates at a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:176-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rampal R, Ahdal J, Kaushik K, Jain R. Current clinical trends in the management of gram positive infections in Indian critical care settings: a survey. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7:2737. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Infectious Diseases Society of America, Spellberg B, Blaser M, et al. Combating antimicrobial resistance: policy recommendations to save lives. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:S397-S428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wong JWH, Ip M, Tang A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage in Asia-Pacific region from 2000 to 2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1489-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dulon M, Peters C, Schablon A, Nienhaus A. MRSA carriage among healthcare workers in non-outbreak settings in Europe and the United States: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Reta A, Mengist A, Tesfahun A. Nasal colonization of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019;18:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Harbarth S, Sax H, Fankhauser-Rodriguez C, Schrenzel J, Agostinho A, Pittet D. Evaluating the probability of previously unknown carriage of MRSA at hospital admission. Am J Med. 2006;119:275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kupfer M, Jatzwauk L, Monecke S, Möbius J, Weusten A. MRSA in a large German University Hospital: male gender is a significant risk factor for MRSA acquisition. GMS Krankenhhyg Interdiszip. 2010;5:Doc11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pomorska-Wesołowska M, Różańska A, Natkaniec J, et al. Longevity and gender as the risk factors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in southern Poland. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hwang JH, Lee JH, Moon MK, Kim JS, Won KS, Lee CS. The usefulness of arbekacin compared to vancomycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1663-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Holland TL, Arnold C, Fowler VG., Jr. Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a review. JAMA. 2014;312:1330-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Stewart CL, Turner MS, Frens JJ, Snider CB, Smith JR. Real-world experience with oritavancin therapy in invasive gram-positive infections. Infect Dis Ther. 2017;6:277-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]