Abstract

Background and Objectives

The Australian National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce is a consortium of 31 Australian health professional organisations developing living, evidence-based guidelines for care of people with COVID-19, which are updated weekly. This article describes the methods used to develop and maintain the guidelines.

Methods

The guidelines use the GRADE methods and are designed to meet Australian NHMRC standards. Each week, new evidence is reviewed, current recommendations are revised, and new recommendations made. These are published in MAGIC and disseminated through traditional and social media. Relevant new questions to be addressed are continually sought from stakeholders and practitioners. For prioritized questions, the evidence is actively monitored and updated. Evidence surveillance combines horizon scans and targeted searches. An evidence team appraises and synthesizes evidence and prepares evidence-to-decision frameworks to inform development of recommendations. A guidelines leadership group oversees the development of recommendations by multidisciplinary guidelines panels and is advised by a consumer panel.

Results

: The Taskforce formed in March 2020, and the first recommendations were published 2 weeks later. The guidelines have been revised and republished on a weekly basis for 24 weeks, and as of October 2020, contain over 90 treatment recommendations, suggesting that living methods are feasible in this context.

Conclusions

The Australian guidelines for care of people with COVID-19 provide an example of the feasibility of living guidelines and an opportunity to test and improve living evidence methods.

Keywords: COVID-19, Guidelines, Living evidence, Methods

What is new?

Key findings

-

•

It is feasible to produce evidence-based guidelines that are updated weekly to reflect new evidence for a vital health issue, during a global crisis.

What this adds to what was known?

-

•

Living evidence synthesis methods are increasingly being used to continually update evidence syntheses and guidance in areas of importance for health decisions.

-

•

Current living guidelines pilots have varying updating cycles, usually in the order of months.

-

•

This work shows that it is possible to develop rigorous living guidelines and update them on a weekly basis.

What is the implication and what should change now?

-

•

Guideline developers should consider using rapid living approaches for important health topics with an evolving evidence base.

1. Introduction

In January 2020, the outbreak of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. By early April 2020, there were 1.2 million cases of COVID-19 and over 69,000 deaths [1]. In the same period, more than 300 COVID-19 clinical trials were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, and numbers continue to grow [2].

As a novel virus, in the early phases of the pandemic clinicians were required to make vital COVID-19 treatment decisions with limited direct evidence. However, an escalating volume of research related to COVID-19 is released daily [3], requiring rapid and ongoing synthesis to ensure guidance for health decisions remains up to date.

Evidence-based guideline development relies on a series of systematic reviews to identify and appraise the research on which recommendations are based. Recommendations can rapidly become out of date as new research is published but not incorporated into the guidelines, with some recommendations already out of date at the time of publication [[4], [5], [6]]. Delays in including evidence in guidelines may contribute to suboptimal quality of care and patient outcomes.

“Living” evidence synthesis methods were developed to enable systematic reviews to be continually updated as new evidence emerges [7]. Living systematic reviews are now conducted across the spectrum of health research [8], and living approaches are being applied to guideline development [9], with pilot living guidelines projects underway in stroke, diabetes, maternal health, and other areas [[10], [11], [12]].

A living approach to guideline development includes rapid prioritization of areas where guidance is needed, continual evidence surveillance, and frequent updating of recommendations. By continually incorporating emerging evidence, these methods ensure that currency of guideline recommendations is maintained [9].

Living approaches are appropriate when

-

1.

Guideline recommendations are a priority for decision-making;

-

2.

Recommendations are likely to change as new evidence emerges; and

-

3.

New research evidence is likely to become available [9].

The decisions made by clinicians caring for patients with COVID-19 unquestionably fit these three criteria.

In late March 2020 the Australian Living Evidence Consortium and Cochrane Australia established the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce [13]. The Taskforce is a partnership of 31 Australian peak health professional bodies (Box 1 ) whose members provide clinical care to people with COVID-19. Taskforce partners collaborate to develop living, evidence-informed guidelines for primary, hospital and critical care of people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. The guidelines are updated weekly. In this article, we describe the methods used to develop and maintain the guidelines.

Box 1. National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce Members as of September 25, 2020.

National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce Members

Australian Living Evidence Consortium∗ (Convenor)

Cochrane Australia (Secretariat)

Australasian Association of Academic Primary Care (AAAPC)

Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM)

Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control (ACIPC)

Australasian College of Paramedicine (ACP)

Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases (ASID)

Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists and Toxicologists (ASCEPT)

Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA)

Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS)

Australian and New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine (ANZSGM)

Australian Association of Gerontology (AAG)

Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN)

Australian College of Midwives (ACM)

Australian College of Nursing (ACN)

Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM)

Australian COVID-19 Palliative Care Working Group (ACPCWG)

Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association (APNA)

Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC)

Australian Sleep Association (ASA [Sleep])

Australian Society of Anaesthetists (ASA [Anaesthesia])

College of Emergency Nursing Australasia (CENA)

CRANAplus

National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO)

Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP)

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG)

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)

Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS)

Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia (SHPA)

Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ)

Thrombosis and Haemostasis Society of Australia and New Zealand (THANZ)

∗The Australian Living Evidence Consortium members are:

Arthritis Australia

Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group (APEG)

Australia and New Zealand Musculoskeletal Clinical Trials Network (ANZMUSC)

Australian and New Zealand Society of Nephrology (ANZSN)

Australian Diabetes Educators Association (ADEA)

Australian Diabetes Society (ADS)

Cochrane Australia

Diabetes Australia

Heart Foundation

KHA-CARI Guidelines

Kidney Health Australia (KHA)

Stroke Foundation

2. Scope and audience

The guidelines provide specific, patient-focused recommendations on management and care of people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, and chemoprophylaxis for people exposed to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The guideline recommendations are intended to be used by individuals responsible for the management and care of people with COVID-19 in Australia.

3. Methods

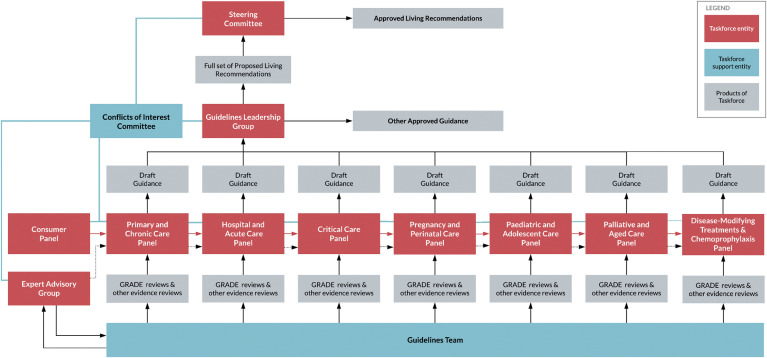

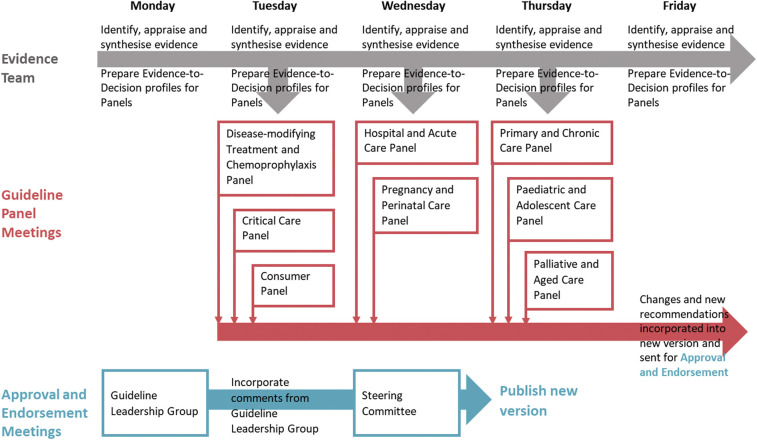

The guidelines are designed to meet the 2016 Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) standard for clinical practice guidelines [14], and the Taskforce is seeking the NHMRC approval. The Taskforce is overseen by a steering committee, comprising representatives from member organisations, which has responsibility for endorsing guideline recommendations. A guidelines leadership group (GLG) oversees daily operations, including the work of guidelines panels, and is advised by a consumer panel. The guideline panels review evidence and make draft recommendations in specific areas of clinical practice, to be approved by the GLG. They are supported by an evidence team that identifies, appraises, and synthesizes evidence (see Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Membership of these groups is described on the Taskforce website [13].

Fig. 1.

Organizational relationships within the Taskforce.

Fig. 2.

Weekly flow of evidence, recommendations, and approval.

3.1. Identification and formulation of clinical questions

Clinical questions are selected and prioritized for living evidence review where they meet the criteria for living evidence synthesis. Over a 2-week period in March 2020, we identified initial questions through a survey of the membership and discussions with leaders of Taskforce organisations; a review of existing guidelines; and discussions with key stakeholders.

Since the publication of the first version of the guidelines, questions are sought on an ongoing basis from the guideline and consumer panels, Taskforce members, and through the Taskforce website. Each week, in-scope questions are prioritized by the panels by

-

1.

Likely impact on patient outcomes,

-

2.

Proportion of clinical population impacted,

-

3.

Extent of variation in current practice,

-

4.

Likelihood of new evidence emerging.

High-priority questions are selected by the GLG. Each priority question is formulated by the evidence team using the Patient, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes (PICO) format, and clinical experts on the panels ensure the questions target areas of urgent clinical uncertainty. Where possible, outcomes are aligned with the COVID-19 Core Outcomes Set [15]. A list of the topics currently addressed by the guidelines is provided in Box 2 , and an up-to-date list is available on the guideline website [13].

Box 2. Guideline topics as of September 25.

As of September, the guideline recommendations cover:

-

•Definition of disease severity

-

•Definition of disease severity for adults

-

•Definition for disease severity for children and adolescents

-

•Monitoring and markers of clinical deterioration

-

•

-

•Disease-modifying treatments

-

•Corticosteroids

-

•Corticosteroids for adults

-

•Corticosteroids for pregnant or breastfeeding women

-

•Corticosteroids for children or adolescents

-

•

-

•Remdesivir

-

•Remdesivir for adults

-

•Remdesivir for pregnant patients

-

•Remdesivir for children or adolescents

-

•

-

•Hydroxychloroquine

-

•Disease-modifying treatments not recommended outside of clinical trials

-

•Aprepitant

-

•Azithromycin

-

•Baloxavir marboxil

-

•Calcifediol

-

•Chloroquine

-

•Colchicine

-

•Convalescent plasma

-

•Darunavir-cobicistat

-

•Favipiravir

-

•Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

-

•Immunoglobulin plus methylprednisolone

-

•Interferon β-1a

-

•Interferon β-1b

-

•Interferon gamma

-

•Lopinavir/ritonavir

-

•Ruxolitinib

-

•Sofosbuvir-daclatasvir

-

•Telmisartan

-

•Umifenovir

-

•

-

•Other disease-modifying treatments

-

•

-

•Chemoprophylaxis

-

•Hydroxychloroquine for postexposure prophylaxis

-

•

-

•Respiratory support in adults

-

•High-flow nasal oxygen therapy

-

•Non-invasive ventilation

-

•Respiratory management of the deteriorating patient

-

•Videolaryngoscopy

-

•Neuromuscular blockers

-

•Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

-

•Prone positioning

-

•Prone positioning for adults

-

•Prone positioning for pregnant and postpartum women

-

•

-

•Recruitment maneuvers

-

•Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

-

•ECMO for adults

-

•ECMO for pregnant and postpartum women

-

•

-

•

-

•Respiratory support in neonates, children and adolescents

-

•Requiring non-invasive respiratory support

-

•High-flow nasal oxygen and non-invasive ventilation

-

•Prone positioning (non-invasive)

-

•Respiratory management of the deteriorating child

-

•Requiring invasive mechanical ventilation

-

•Prone positioning (mechanical ventilation)

-

•Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

-

•Recruitment maneuvers

-

•Neuromuscular blockers

-

•High-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV)

-

•Videolaryngoscopy

-

•Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

-

•

-

•Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis

-

•VTE prophylaxis for adults

-

•VTE prophylaxis for pregnant and postpartum women

-

•

-

•Therapies for pre-existing conditions in patients with COVID-19

-

•ACEIs/ARBs in patients with COVID-19

-

•ACEIs in postpartum women

-

•Steroids for people with asthma or COPD with COVID-19

-

•

-

•Pregnancy and perinatal care

-

•Antenatal corticosteroids

-

•Mode of birth

-

•Delayed umbilical cord clamping

-

•Skin-to-skin contact

-

•Breastfeeding

-

•Rooming-in

-

•

-

•

Child and adolescent care

3.2. Search and selection methods

An information specialist oversees evidence surveillance and undertakes searches of databases and other sources. To avoid duplication, evidence surveillance combines daily horizon scans of several COVID-19 sources, including organisations producing COVID-19 guidance, plus targeted searches for specific PICO questions as they are prioritized. The purpose of the horizon scan is to be aware of new evidence syntheses (systematic reviews, rapid reviews, living reviews) and primary studies that fall within the scope of the guideline (see Table 1 ). Several autoalerts are run daily or weekly in PubMed to supplement the horizon-scanning activities.

Table 1.

COVID-19 sources scanned daily

| Type | Sources |

|---|---|

| All COVID-19 research | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Research Articles Database Comprises systematic searches of over 20 sources, including various bibliographic databases, trial registers, manuscript preprint servers (e.g., medRxiv) and handsearching of selected gray literature sources. |

| COVID-19 systematic reviews, rapid summaries and other syntheses | Sources of completed systematic reviews:

|

| COVID-19 primary studies | Living evidence map and living systematic review of COVID-19 studies (covid-nma.org) Identifies randomized trials, nonrandomized studies and case series from daily screening of searches of PubMed, Chinarxiv, and MedRxiv. Provides study characteristics, risk of bias assessments and forest plots. |

| Other sources | NSW Health COVID-19 Critical Intelligence Unit Daily Evidence Digest |

The evidence team also liaises with several international groups who are sourcing and conducting research and evidence syntheses within the guideline scope to minimize duplication and ensure rapid access to relevant research.

As new questions are prioritized, existing search surveillance methods are checked to ensure they cover the new questions, and the search is updated or expanded as needed.

Articles are eligible for inclusion if they report results of primary research or systematic reviews relevant to one of the PICO questions. PICO questions are occasionally structured to include evidence from other, similar diseases (such as other viral pneumonia), to provide additional indirect evidence for formulating recommendations. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are developed for each PICO question.

Studies retrieved by the search are uploaded into Covidence for screening by at least two members of the evidence team. Disagreements are resolved through discussion and, if necessary, a third reviewer adjudicates. Full-text articles are screened using the same process, with expert clinical input as required.

3.3. Assessment of evidence and formulation of recommendations

3.3.1. Use of GRADE and MAGIC

The guideline uses the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [16,17] methodology, as it is recommended as best practice by the NHMRC, the body responsible for approving clinical practice guidelines in Australia, and is used by many international organisations, including the World Health Organization and Cochrane, enabling collaboration [18,19]. GRADE is a transparent framework for developing and presenting summaries of evidence and provides a systematic approach for making clinical practice recommendations.

Development is supported by the online guideline development and publication platform “MAGIC” (Making GRADE the Irresistible Choice) [16,17]. Using MAGIC allows collaboration across locations, and rapidly publishes updated recommendations in an easily accessible web format.

3.3.2. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

The evidence team extracts data using standardized forms. Data are extracted independently by two reviewers and disagreements are resolved through discussion and, if necessary, a third reviewer adjudicates. Extracted data are cross-referenced with an outcome matrix to ensure that all important outcomes are analyzed, and we cross-check our assessments with other groups undertaking rigorous syntheses. A summary table of study characteristics is used to group studies for analysis, in accordance with prespecified questions.

Systematic reviews are assessed using AMSTAR2 [20], and the risk of bias assessment of included studies from the review is used where available. Individual primary studies are assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool for randomized trials [21] and the ROBINS-I tool for nonrandomized studies [22].

3.3.3. Evidence synthesis

Where an existing systematic review is available and up to date, additional synthesis is not undertaken, and reviews are monitored for further updates. Where an existing systematic review is available but not up to date (or becomes out of date), a limited update may be conducted to integrate new studies. Where primary studies are available to answer a clinical question, a systematic review is initiated and synthesis methods selected as appropriate to the question, in accordance with Cochrane standards [21].

3.3.4. Development of the recommendations

For each question, the evidence team develops evidence-to-decision tables following the GRADE processes. Where needed, specialist expertise is sought from the expert advisory group. The complete evidence profiles and rationales for recommendations are included in the guidelines.

Seven guideline panels have been convened:

-

•

Primary and chronic care

-

•

Hospital and acute care

-

•

Critical care

-

•

Pregnancy and perinatal care

-

•

Pediatric and adolescent care

-

•

Palliative and aged care panel

-

•

Disease-modifying treatment and chemoprophylaxis

Panels are intentionally diverse across disciplines, setting, geography, and gender. Members of panels are sought through consultation with Taskforce members and calls for expressions of interest. New panel members are recruited, and new panels convened, as areas of need arise.

Panels discuss and revise draft recommendations within their scope at weekly meetings. Panels consider each of the GRADE domains, including benefits and harms, the certainty of the evidence, resources, feasibility, acceptability, and equity in formulating their decisions. Consumer representatives particularly consider whether strong or varying patient preferences and values are likely to impact on the nature or implementability of the recommendations.

A recommendation is rated

-

•

strong when most or all individuals will be best served by the recommended course of action;

-

•

conditional when not all individuals will be best served by the recommended course of action and there is a need to consider the individual patient's circumstances, preferences, and values.

For some topics, there is insufficient evidence on which to base a recommendation; however, panels believe it important to provide advice. Advice about these topics is developed based on consensus expert opinion (guided by any relevant evidence) and labeled as Consensus Recommendations or Practice Statements.

Draft recommendations from the panels are reviewed and approved by the GLG and endorsed by the steering committee before publication.

On publication, each recommendation is labeled as “Updated” or “New”. Updated recommendations are existing recommendations where the strength or the direction of the recommendation has changed.

Care is taken to coordinate the work of the panels and ensure consistency in recommendations across panels. Guideline panel chairs and evidence team members meet regularly, and panel chairs sit on the GLG where they review the recommendations across each of the panels.

3.4. Consumer involvement

The Taskforce has partnered with the Consumers Health Forum of Australia, the peak national health consumer body, to co-convene a consumer panel. The panel consists of eight to ten consumers who advise the GLG on

-

•

new clinical questions and high-priority topics,

-

•

relative importance of different outcomes, and

-

•

feedback on guideline recommendations.

The co-chairs of the consumer panel also represent the panel on the GLG.

3.5. Considering the needs of specific populations

The Taskforce is mindful that indigenous peoples or other population groups (including culturally and linguistically diverse communities) may have specific needs in relation to COVID-19 care. Our guideline panels include a diversity of representation, including indigenous peoples and remote and regional health practitioners. The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation and the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine are both members of the Taskforce. Searches cover all population groups, with no limits on the patients or population of studies, other than that they must have a diagnosis or suspicion of COVID-19.

In the early phase of the Taskforce, it became evident that specialty panels would be required for specific subpopulations. The Taskforce established separate panels for pregnancy and perinatal care, pediatric and adolescent care, and palliative and aged care. These panels develop recommendations specific to these population (e.g., care during labor and childbirth), and adapt existing recommendations (e.g., use of antiviral medicines in infants).

3.6. Funding and conflicts of interest

The Taskforce is funded by the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, The Ian Potter Foundation, the Walter Cottman Endowment Fund, and the Lord Mayors’ Charitable Foundation.

All individuals who participate in decision-making related to the development of the guidelines complete a declaration of interests. These statements are reviewed by the Taskforce executive and, if needed, by an independent conflicts of interest committee. This committee also provides advice on management of competing interests. The membership of this committee is described on the Taskforce website [13]. On the advice of the committee, panel members may be required to remove themselves from discussions related to specific conflicts.

3.7. Dissemination and evaluation

3.7.1. Dissemination

Weekly guideline updates are disseminated through general and health media, including traditional and social media channels, and distributed to the members of the Taskforce for dissemination. Each week, a “Taskforce Communiqué” is sent to all member organisations, partners and funders of the Taskforce, as well as subscribers to the Taskforce website (and is available online on the Taskforce website [13]). The Communiqué provides an overview of the work of the Taskforce for that week and includes content that Taskforce members can adapt for communications with their members.

3.7.2. Evaluation

A process evaluation is being undertaken to continually improve processes and outputs of the Taskforce and guidelines project, and inform future living guideline projects. Each month, experiences of participants in the Taskforce are captured through online surveys, semistructured interviews and a stocktake of activity. Results are provided monthly to the Taskforce steering committee.

An impact evaluation will examine the influence of the guidelines on care of people with COVID-19, identifying the extent to which health decision-makers were aware of the guidelines; valued the guidelines; and used the guidelines to inform decision-making.

4. Results and Discussion

The Taskforce was formed in late March 2020; the first version of the guidelines was published 2 weeks later and included 10 recommendations. Using the methods described previously, the guidelines have been revised, updated, and republished each week since.

By early October, the evidence team of 11 full-time equivalent staff working with seven guideline panels and over 230 individuals (clinicians, policymakers, and others) had screened more than 5,000 citations, appraised, and synthesized 53 randomized trials, 13 nonrandomized studies and 12 systematic reviews. Collectively this evidence had informed 92 recommendations addressing 81 topics (version 24, 1 October 2020).

The Australian Guidelines for the Management and Care of People with COVID-19 provide a large-scale test case for living approaches to the GRADE-based guideline development. The weekly update schedule is the most frequent of which we are aware, and significantly more rapid than other living guidelines projects [[10], [11], [12]]. This is commensurate with the extraordinarily rapid emergence of evidence related to management of COVID-19 [23].

Our experience of 24 successful weekly cycles suggests that very frequent updating is feasible, even during a time of significant disruption. The short update cycles require all contributors to be agile and act collaboratively, and depend on strong project management.

Others have noted that rapid reviews are particularly challenging during COVID-19 [24], and the team has faced challenges in developing the guidelines. As a new Taskforce, the project team moved quickly to both rapidly support recommendation development and publication, whereas simultaneously establishing infrastructure, recruiting staff, and developing the workflows to deliver living guidelines. It took several weeks to establish stability in the team and processes. Having a team of experienced methodologists familiar with living evidence synthesis methods was crucial. With all team members working remotely, technologies such as Zoom and Slack have been indispensable in enabling the rapid workflows.

Globally, several groups have also recognized the particular value of living evidence synthesis approaches in the context of a novel disease with such a swiftly evolving evidence base. Cochrane has rapidly produced living systematic reviews (LSRs) addressing the value of convalescent plasma and rehabilitation interventions for people with COVID-19 [25,26], on signs and symptoms, and antibody tests to identify people with COVID-19 [27,28]. The Cochrane convalescent plasma LSR provides a clear demonstration of why these approaches are useful. The initial version, published in May, included only eight studies, predominantly case series, with a total of just 32 participants. The first update, published 2 months later, included 20 studies (one randomized and 19 nonrandomized) with over 5,000 participants, and also identified 50 ongoing randomized trials [25].

Groups outside Cochrane have also recognized the value of living approaches to guide decision-making during the pandemic, and many research teams are developing suites of COVID-19-related LSRs. Groups such as The LIVING Project (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003293), COVID-NMA (https://covid-nma.com/), and the COVID-19 L·OVE Working Group (https://www.epistemonikos.cl/living-evidence/) are all applying living methods to ensure their reviews are continually up to date, and the number of COVID-19-related living systematic reviews produced by these and other researchers is increasing [[29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]].

The existence of LSRs produced by international research groups and other prefiltered and preappraised evidence sources, including COVID-19-specific research databases, was a major enabler of our work and reduced duplication of effort.

Living methods are also beginning to be applied to other guideline development for COVID-19, for example, the World Health Organization guideline for COVID-19 drugs [37] and the BMJ Rapid Recommendation on remdesivir [38]; however, we are not aware of other living guideline programs that match the scope or frequency of updating achieved by the Taskforce.

The Taskforce brings together 31 Australian peak health professional bodies whose members provide care to people with COVID-19. The willingness of these organisations to collaborate, quickly identify representatives and panel members, and establish rapid processes for recommendation endorsement has been crucial to the successful delivery of weekly guideline updates. Similarly, the commitment of individual clinicians and others to weekly panel meetings has been outstanding, especially given increased workloads resulting from the pandemic. Support from NHMRC was also vital in ensuring the guidelines meet NHMRC standards.

5. Conclusions

The Australian Guidelines for the Management and Care of People with COVID-19 provide an important example of the feasibility of rapid living GRADE-based guideline development, and an opportunity to robustly test and improve living guideline development methods. Results of the process and impact evaluations will provide useful insights to guide future work in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the members of the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce for their magnificent contributions to the work described in this article. Steering committee: Sharon McGowan (Chair), Nicola Ballenden, Terri-Lee Barrett, Vanessa Beavis, James Beckford Saunders, Tanya Buchanan, Marina Buchanan-Grey, Dawn Casey, Marita Cowie, Joseph Doyle, Mark Frydenberg, Danijela Gnjidic, Sally Green, Rohan Greenland, Ken Griffin, Stephan Groombridge, Louise Hardy, Alison Hodak, Anthony Holley, Vase Jovanovska, Sabina Knight, Kristin Michaels, Peter Morley, Julia Morphet, Suzi Nou, Phillip Russo, Megan Sarson, Alan Young. Executive Team: Julian Elliott, Rhiannon Tate, Britta Tendal, Sarah Norris, Bronwyn Morris-Donovan, Joshua Vogel, Sharon Gurry, Eloise Hudson, Shauna Hurley, Declan Primmer, Samantha Timms, Susan Whicker. National Guidelines Leadership Group: Julian Elliott (Co-Chair), Sutapa Mukherjee (Co-Chair), Joshua Vogel (Deputy Chair), Jason Agostino, Karen Booth, Lucy Burr, Lyn Byers, Peter Cameron, Megan Cooper, Allen Cheng, Peter Fowler, Mark Frydenberg, Alan Glanville, Caroline Homer, Karin Leder, Steve McGloughlin, Brendan McMullan, Ewen McPhee, Brett Mitchell, Mark Morgan, Paul Myles, Chris O'Donnell, Michael Parr, Jane Phillips, Rebecca Randall, Wayne Varndell, Ian Whyte, Leeroy William. Consumer Panel: Rebecca Randall (Chair), Richard Brightwell, Lynda Condon, Amrita Deshpande, Adam Ehm, Monica Ferrie, Joanne Muller, Lara Pullin, Elizabeth Robinson, Adele Witt. Primary and Chronic Care Panel: Sarah Larkins (Co-Chair), Mark Morgan (Co-Chair), Georgina Taylor (Deputy Chair), Jason Agostino, Paul Burgess, Penny Burns, Lyn Byers, Kirsty Douglas, Ben Ewald, Dan Ewald, Dianna Fornasier, Sabina Knight, Carmel Nelson, Louis Peachey, David Peiris, Mieke van Driel, Lucie Walters, Ineke Weaver. Hospital and Acute Care Panel: Lucy Burr (Chair), Simon Hendel (Deputy Co-Chair), Kiran Shekar (Deputy Co-Chair), Bronwyn Avard, Kelly Cairns, Allan Glanville, Nicky Gilroy, Paul Myles, Robert O'Sullivan, Owen Robinson, Chantal Sharland, Sally McCarthy, Peter Wark.

Critical care panel: Steve McGoughlin (Co-Chair), Priya Nair (Co-Chair), Carol Hodgson, (Deputy Chair), Melissa Ankravs, Craig French, Kim Hansen, Sue Huckson, Jon Iredell, Carrie Janerka, Rose Jaspers, Ed Litton, Stephen Macdonald, Sandra Peake, Ian Seppelt. Pregnancy and Perinatal Care Panel: Caroline Homer (Co-Chair), Vijay Roach (Co-Chair), Michelle Giles (Deputy Co-Chair), Clare Whitehead (Deputy Co-Chair), Wendy Burton, Teena Downton, Glenda Gleeson, Adrienne Gordon, Jenny Hunt, Jackie Kitschke, Nolan McDonnell, Philippa Middleton, Jeremy Oats. Pediatric and Adolescent Care Panel: Asha Bowen (Co-Chair), Brendan McMullan (Co-Chair), David Tingay (Deputy Co-Chair), Nan Vasilunas (Deputy Co-Chair), Lorraine Anderson, James Best, Penny Burns, Simon Craig, Simon Erickson, Nick Fancourt, Zoy Goff, Vimbai Kapuya, Catherine Keyte, Lorelle Malyon, Danielle Wurzel. Palliative and Aged Care Panel: Meera Agar (Co-Chair), Richard Lindley (Co-Chair), Natasha Smallwood (Deputy Chair), Mandy Callary, Michael Chapman, Philip Good, Peter Jenkin, Deidre Morgan, Vasi Naganathan, Velandai Srikanth, Penny Tuffin, Elizabeth Whiting, Leeroy William, Patsy Yates. Disease-Modifying Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis Panel: Bridget Barber, Jane Davies, Josh Davis, Dan Ewald, Michelle Giles, Amanda Gwee, Karin Leder, Gail Matthews, James McMahon, Trisha Peel, Chris Raftery, Megan Rees, Jason Roberts, Ian Seppelt, Tom Snelling, Brad Wibrow. Expert Advisory Group: Ross Baker, Jennifer Curnow, Briony Cutts, Anoop Enjeti, Andrew Forbes, Prahlad Ho, Adam Holyoak, Helen Liley, James McFadyen, Zoe McQuilten, Eileen Merriman, Helen Savoia, Chee Wee Tan, Huyen Tran, Chris Ward, Katrina Williams. Cardiac Arrest Working Group: Neil Ballard, Samantha Bendall, Neel Bhanderi, Lyn Byers, Simon Craig, Dan Ellis, Dan Ewald, Craig Fairley, Brett Hoggard, Minh Le Cong, Peter Morley, Priya Nair, Andrew Pearce. Evidence Team: Britta Tendal, Steve McDonald, Tari Turner, Joshua Vogel, David Fraile Navarro, Heath White, Samantha Chakraborty, Saskia Cheyne, Henriette Callesen, Sue Campbell, Jenny Ring, Agnes Wilson, Tanya Millard, Melissa Murano. Observational Data Working Group: David Henry (Co-Chair), Sallie Pearson (Co-Chair), Douglas Boyle, Kendal Chidwick, Wendy Chapman, Craig French, Chris Pearce, Tom Snelling. Independent Conflicts of Interest Committee: Lisa Bero (Chair), Quinn Grundy, Joel Lexchin, Barbara Mintzes.

The authors would like to acknowledge the member organisations: Australian Living Evidence Consortium (Convenor), Cochrane Australia (Secretariat), Australasian Association of Academic Primary Care, Australian Association of Gerontology, Australasia College for Emergency Medicine, Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control, Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases, Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists and Toxicologists, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, Australian & New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine, Australian College of Critical Care Nurses, Australian College of Midwives, Australian College of Nursing, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, Australian COVID-19 Palliative Care Working Group, Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association, Australian Resuscitation Council, Australasian Sleep Association, Australian Society of Anaesthetists, Australasian College of Paramedicine, College of Emergency Nurses Australasia, CRANAplus, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Royal Australian College of Surgeons, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia, Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, Thrombosis and Haemostasis Society of Australia and New Zealand.

The authors would also like to acknowledge their partners: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Cochrane, Consumers Health Forum of Australia, Covidence, Hereco, MAGIC, NPS MedicineWise, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University.

The authors would like to acknowledge their funders: Australian Government Department of Health, Victorian Government Department of Health and Human Services, The Ian Potter Foundation, Walter Cottman Endowment Fund, managed by Equity Trustees, Lord Mayors' Charitable Foundation.

Authors' contributions: All authors developed and documented the methods described in the article on behalf of the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. T.T. prepared the first draft of the manuscript and incorporated the feedback to produce the submitted version of the manuscript, which all of the authors approved.

The National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health, the Victorian Government Department of Health and Human Services, the Ian Potter Foundation and the Walter Cottman Endowment Fund, managed by Equity Trustees, and the Lord Mayors’ Charitable Foundation. The funders played no role in the development of the methods, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Author statement: Britta Tendal: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Joshua P. Vogel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Steve McDonald: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Sarah Norris: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Miranda Cumpston: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Heath White: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Karin Leder: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, David Fraile Navarro: Methodology,: Writing - review & editing, Saskia Cheyne: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Samantha Chakraborty: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Melissa Murano: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Tanya Millard: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Henriette E Callesen: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Rakibul M Islam: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Julian Elliott: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing, Tari Turner: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. on behalf of the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce.

Conflicts of interest: J.E. is the cofounder and CEO of Covidence, a nonprofit online platform for efficient systematic review production. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

References

- 1.Salyer K. COVID-19: what to know about the coronavirus pandemic on 6 April: World Economic Forum. 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/covid-19-what-to-know-about-the-coronavirus-pandemic-on-6-april/ Available at.

- 2.Mehta H.B., Ehrhardt S., Moore T.J., Segal J.B., Alexander G.C. Characteristics of registered clinical trials assessing treatments for COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e039978. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidahic M., Nujic D., Runjic R., Civljak M., Markotic F., Lovric Makaric Z. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:161. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderson L.J., Alderson P., Tan T. Median life span of a cohort of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guidelines was about 60 months. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez Garcia L., Sanabria A.J., Garcia Alvarez E., Trujillo-Martin M.M., Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I., Kotzeva A. The validity of recommendations from clinical guidelines: a survival analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186(16):1211–1219. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuman M.D., Goldstein J.N., Cirullo M.A., Schwartz J.S. Durability of class I American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guideline recommendations. JAMA. 2014;311:2092–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott J.H., Synnot A., Turner T., Simmonds M., Akl E.A., McDonald S. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khamis A.M., Kahale L.A., Pardo-Hernandez H., Schunemann H.J., Akl E.A. Methods of conduct and reporting of living systematic reviews: a protocol for a living methodological survey. F1000Res. 2019;8:221. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18005.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akl E.A., Meerpohl J.J., Elliott J., Kahale L.A., Schunemann H.J. Living Systematic Review N. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.English C., Bayley M., Hill K., Langhorne P., Molag M., Ranta A. Bringing stroke clinical guidelines to life. Int J Stroke. 2019;14(4):337–339. doi: 10.1177/1747493019833015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White H., Tendal B., Elliott J., Turner T., Andrikopoulos S., Zoungas S. Breathing life into Australian diabetes clinical guidelines. Med J Aust. 2020;212:250–251 e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel J.P., Dowswell T., Lewin S., Bonet M., Hampson L., Kellie F. Developing and applying a 'living guidelines' approach to WHO recommendations on maternal and perinatal health. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(4):e001683. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caring for people with COVID-19 2020. https://covid19evidence.net.au/ Available at.

- 14.2016 NHMRC standards for guidelines: national health and medical research Council (NHMRC) https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/standards Available at.

- 15.Tong A., Elliott J., Cesar Azevedo L., Baumgart A., Bersten A., Cervantes L. Core outcomes set for people with COVID-19. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1622–1635. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Making GRADE the Irresistible Choice (MAGIC) project. 2018. http://magicproject.org/ Available at.

- 17.Alonso-Coello P., Schünemann H.J., Moberg J., Brignardello-Petersen R., Akl E.A., Davoli M. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.2016 NHMRC Standards for Guidelines https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/standards: National Health and Medical Research Council. 2016. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/standards Available at.

- 19.World Health Organization . 2nd ed. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shea B.J., Reeves B.C., Wells G., Thuku M., Hamel C., Moran J. Amstar 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins J., Thomas J., Chandler J., Cumpston M., Li T., Page M. Cochrane; Chichester (UK): 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., Elbers R.G., Blencowe N.S., Boutron I. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q., Allot A., Lu Z. Keep up with the latest coronavirus research. Nature. 2020;579:193. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tricco A.C., Garritty C.M., Boulos L., Lockwood C., Wilson M., McGowan J. Rapid review methods more challenging during COVID-19: Commentary with a focus on 8 knowledge synthesis steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;126:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piechotta V., Chai K.L., Valk S.J., Doree C., Monsef I., Wood E.M. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD013600. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negrini F., De Sire A., Andrenelli E., Lazzarini S.G., Patrini M., Ceravolo M.G. Rehabilitation and COVID-19: the Cochrane Rehabilitation 2020 rapid living systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56:642–651. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Struyf T., Deeks J.J., Dinnes J., Takwoingi Y., Davenport C., Leeflang M.M. Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID-19 disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD013665. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deeks J.J., Dinnes J., Takwoingi Y., Davenport C., Spijker R., Taylor-Phillips S. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD013652. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Update to living systematic review on prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m2810. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrenelli E., Negrini F., de Sire A., Arienti C., Patrini M., Negrini S. Systematic rapid living review on rehabilitation needs due to COVID-19: update to May 31st, 2020. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56(4):508–514. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baladia E., Pizarro A.B., Ortiz-Munoz L., Rada G. Vitamin C for COVID-19: a living systematic review. Medwave. 2020;20(6):e7978. doi: 10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Sire A., Andrenelli E., Negrini F., Negrini S., Ceravolo M.G. Systematic rapid living review on rehabilitation needs due to COVID-19: update as of April 30th, 2020. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56(3):354–360. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez A.V., Roman Y.M., Pasupuleti V., Barboza J.J., White C.M. Hydroxychloroquine or Chloroquine for treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19: a living systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:287–296. doi: 10.7326/M20-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schunemann H.J., Khabsa J., Solo K., Khamis A.M., Brignardello-Petersen R., El-Harakeh A. Ventilation techniques and risk for transmission of coronavirus disease, including COVID-19: a living systematic review of multiple streams of evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:204–216. doi: 10.7326/M20-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thombs B.D., Bonardi O., Rice D.B., Boruff J.T., Azar M., He C. Curating evidence on mental health during COVID-19: a living systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2020;133:110113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verdugo-Paiva F., Izcovich A., Ragusa M., Rada G. Lopinavir-ritonavir for COVID-19: a living systematic review. Medwave. 2020;20(6):e7967. doi: 10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamontagne F., Agoritsas T., Macdonald H., Leo Y.S., Diaz J., Agarwal A. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m3379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rochwerg B., Agarwal A., Zeng L., Leo Y.S., Appiah J.A., Agoritsas T. Remdesivir for severe covid-19: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2020;370:m2924. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]