Abstract

Ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 (UHRF1) has been reported to play an important role in breast carcinogenesis. This work investigated the correlation of UHRF1 DNA level in plasma with clinical characteristics of breast cancer and its clinical significance in breast cancer diagnosis. The expression of UHRF1 in primary breast cancer tissue was examined by Western blot. The UHRF1 DNA levels in plasma and UHRF1 mRNA expression in tissues were determined by accurate real‐time quantitative PCR. The associations of UHRF1 levels with clinical variables were evaluated using standard statistical methods. The UHRF1 DNA in plasma of 229 breast cancer patients showed higher expression than healthy controls, which showed high specificity up to 76.2% at a sensitivity of 79.2%, and was significantly associated with c‐erbB2 positive status, cancer stage and lymph node metastasis. High UHRF1 DNA level in plasma was significantly associated with short progression‐free survival. The UHRF1 DNA level in plasma is highly correlative with breast cancer and its status and stage, and may be a potential independent diagnostic and prognostic factor for both breast cancer and the survival of breast cancer patients.

Breast cancer is the most common malignant disease in women. Its prevalence rate has exhibited a clear increase in China. Furthermore, the mortality rate of breast cancer has risen by 38.9% in the past 20 years.1 Current prognostic criteria only poorly predict the metastasis risk for an individual breast cancer patient due to a lack of specific biomarkers.2 Thus, new prognostic biomarkers are urgently needed to identify breast cancer patients and those at the highest risk for developing metastasis.

Gene‐expression signatures of human primary breast cancers have shown more accurate prediction than current prognostic criteria.3, 4 ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 (UHRF1) is a newly discovered gene reported to have a function in maintaining DNA methylation by helping recruit DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) to hemimethylated DNA. Kim et al.5 demonstrated its new role as a transcriptional corepressor in recruitment of histone methyltransferase G9a and other chromatin modifying enzymes to target promoters, and pointed out its dynamic regulation mode in cancer cells. The functional research of UHRF1 have made it a novel diagnostic marker in lung and bladder cancer.6, 7 Ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1‐induced epigenetic changes, involving DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin remodeling and recruitment of transcriptional complex on the breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1) promoter, are responsible for BRCA1 silencing in sporadic breast cancer.8 These findings indicate that UHRF1 might play an important role in cancer development.

Cancer patients generally exhibit an increasing amount of circulating DNA that comes from cancer tissues.9, 10, 11 However, it is difficult to establish a unitary method for detection of the circulating DNA among different kinds of cancers. Moreover, the clinical values of circulating DNA significantly vary in different cancers, which restricts the application of a circulating DNA test as a general tool for cancer diagnosis, despite being non‐invasive. For example, the circulating DNA concentration is not sensitive or specific enough for a diagnosis of ovarian cancer.12 In contrast, the circulating DNA level is a strong and independent prognostic predictor in Hodgkin's lymphoma and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma.13 Recently, the circulating DNA level has been quantified with a real‐time quantitative PCR method for estimating its diagnostic or prognostic value in early breast cancer patients.14 This work investigated the correlation of the UHRF1 DNA level in plasma with clinical characteristics of breast cancer and its clinical significance in breast cancer diagnosis.

To explore the clinical value of UHRF1 DNA as a biomarker of breast cancer, the expression of UHRF1 in primary breast cancer tissue was examined using western blot and the UHRF1 levels in plasma were determined with real‐time quantitative PCR. The statistical analysis indicated that the UHRF1 level in plasma could be used as an independent factor with acceptable specificity and sensitivity for predicting the status and stage of breast cancer and the survival of breast cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Fresh frozen cancer tissues were studied from 62 breast cancer patients who were first diagnosed by pathology section detection in Jiangsu Cancer Hospital from July 2008 to October 2010. The samples were obtained from breast puncture biopsy guided by color Doppler ultrasound. Their blood samples were collected with a volume of 5 mL at diagnosis, which was equally divided into two centrifuge tubes with EDTA as anticoagulant. Tumor adjacent tissues in 24 breast cancer patients and 43 blood samples from healthy volunteers were studied as negative controls. A total of 229 plasma samples were obtained from breast cancer patients, including 111 first‐diagnosed patients and 56 relapsed or refractory patients in the same hospital between July 2008 and December 2010. The 56 relapsed or refractory patients were originally treated between April 2005 and September 2010 and were used for the progression‐free survival analysis. Their median follow up was 25.5 months. To avoid contamination of blood cells, all blood samples were isolated using two consecutive centrifugations at 2500g for 10 min at 4°C to obtain the plasma samples, which were stored at −80°C.

The clinical data of these patients including the results of immunohistochemical evaluation were collected from the database of the hospital. Any change in a patient's treatment or progress was entered into the database. All samples were used after the patients and healthy volunteers had provided informed consent and the institution provided authorization. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital.

Cell lines

Breast cancer cell line MDAB231 and normal breast cell line Hs578Bst were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai Cell Bank (Shanghai, China), and maintained in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% bovine fetal serum (Gibco). The extraction of proteins was carried out using the Bio‐Rad BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA).

Western blotting analysis

For the western blot analysis, 10 μg of protein extract was electrophoresed with denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gels (12%), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, MA, USA) and then incubated with UHRF1 antibody (mouse, ab57083; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 1:500 dilution with blocking buffer. The membrane was then washed four times with tris buffered saline, with Tween‐20 (TBST) and treated with 1:10 000 dilution of peroxidase‐mouse anti‐human IgG (BM2002; Boster, Wuhan, China) to detect UHRF1. The signals were detected using infrared imaging SuperSignal West Femto Trial Kit (LC142917; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). As a control, β‐actin antibody (mouse, ab40864; Abcam) diluted with the same buffer was used in the incubation step for β‐actin detection.

Gene extraction and cDNA synthesis

RNA was extracted from cancer tissue using a commercial kit, SV Total RNA Isolation system (Promega, Madsion, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Circulating DNA was extracted from 200 μL plasma using a Nucleospin plasma XS Kit (Macherey‐Nagel, D‐52355 Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized in a total volume of 20 μL with 50 ng total RNA using the First strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Beijing, China).

Real‐time PCR analysis

The TaKaRa premix EX Taq kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) was used to detect the presence of UHRF1 in samples using sense primer AAGGTGGAGCCCTACAGTCTC and antisense primer CACTTTACTCAGGAAC AACTGGAAC. A FAM dye (TaKaRa) labeled probe, 5′‐(FAM) CATCAGAGAGGACAAGAGCAACGCC (Eclipse)‐3′, was used to trace the signal. PCR was performed using a LightCycler 1.5 (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) with 20 μL mixture containing 10 μL of premix EX Taq Mix (containing NTP, buffer, polymerase), 0.8 μL probe, 0.4 μL primers and 2 μL DNA extract by incubation at 95°C for 20 s and then 40 cycles circulating at 95°C for 5 s, 55°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s. Ct values were derived using a computer.15

The standard curve of UHRF1 DNA was composed of five 10‐fold dilutions of the plasmid DNA, which was prepared by connecting the purified PCR product of UHRF1 DNA with plasmid (PMD18T; TaKaRa), and then transforming the plasmid into E. coli (DH5α), followed by selection and culture of the positive clones and extraction of UHRF1 DNA. The content of UHRF1 in the standard plasmid was detected using spectrophotometry.

Statistical analysis

To assess whether circulating DNA might discriminate breast cancer patients and healthy individuals, the sensitivity and specificity were estimated at different Ct values, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was made according to the report by Hanley and McNeil.16

Kaplan–Meier plots and a log rank test were used to determine differences among the different groups. Multivariate analysis was carried out using Cox proportional hazard regression with a confidence interval of 95% to examine whether the UHRF1 level is an independent prognostic factor for survival.

All analyses were performed with spss 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows. P‐values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

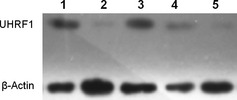

Western blot analysis of UHRF1

Western blot analysis of the protein extracts from MDAB231 cells, breast cancer tissue and tissue adjacent to the breast cancer showed a band of UHRF1 at 90 kDa (Fig. 1). The expression levels of UHRF1 in MDAB231 cells and breast cancer tissues were obviously higher than those in tissues adjacent to the breast cancer. Normal tissue and cells did not show detectable expression of UHRF1.

Figure 1.

Expression of ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1(UHRF1) in MDAB231 cells (1), normal cells (2), breast cancer tissue (3), adjacent tissues (4) and normal breast tissue (5) using β‐actin as a loading control.

Quantification test of circulating DNA

Table 1 summarizes the quantitative assay results of total circulating DNA using spectrophotometry. In plasma samples from 229 patients, the mean value of circulating DNA concentration was 75.01 ng/mL, which was significantly higher than the mean concentration of 23.55 ng/mL observed in 43 controls (P < 0.05). The circulating DNA concentration in breast cancer patients did not correlate with their age, cancer stage, cancer size and lymph node metastasis.

Table 1.

Average circulating DNA levels in patients and controls

| Patients | Number of cases | DNA (ng/mL) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total average level | 229 | 75.0 | |

| Age | 0.152 | ||

| <50 years | 92 | 84.4 | |

| ≥50 years | 137 | 63.5 | |

| Stage | 0.824 | ||

| Early | 151 | 73.6 | |

| Advanced | 78 | 77.1 | |

| Cancer size | 0.175 | ||

| <2 cm | 123 | 86.4 | |

| ≥2 cm | 106 | 65.6 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.426 | ||

| No | 137 | 81.8 | |

| Yes | 92 | 69.4 | |

| Control | 43 | 23.6 | |

x 2 test.

Ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 levels

The expression levels of UHRF1 mRNA in 62 tissue samples from patients with breast cancer and 24 tissues adjacent to the breast cancer were detected using real‐time quantitative PCR. The median Ct values of UHRF1 mRNA were 28.21 (range, 22.30–33.45) and 33.47 (range, 30.58–37.02) in cancer tissues and tissues adjacent to the breast cancer, respectively, with a P‐value less than 0.05, indicative of a significant difference. The circulating UHRF1 DNA of all 229 patients gave a median Ct value of 28.44 (range, 23.11–33.71), while 43 healthy samples showed a median Ct value of 33.19 (range, 28.14–36.45). Again, this showed a significant difference (P < 0.05). From the standard curve, the median copies of circulating UHRF1 DNA were 1.86 × 107 copies/mL and 1.26 × 106 copies/mL in patients and healthy controls, respectively.

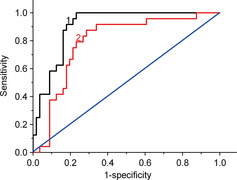

The diagnostic accuracy of UHRF1 levels was evaluated using ROC analysis (Fig. 2). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.906 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.843–0.969) between tissue UHRF1 mRNA and 0.794 (95% CI, 0.688–0.899) between circulating UHRF1 DNA of patients and healthy controls. It suggests that detecting the tissue UHRF1 mRNA or circulating UHRF1 DNA level could discriminate breast cancer patients from healthy individuals.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for UHRF1 level in 62 cancer tissues and 24 tissues adjacent to the cancer (1), and 229 patient plasma and 43 healthy plasma samples (2).

Sensitivity and specificity of tissue mRNA and circulating DNA of UHRF1 were calculated at different cut‐off values. Table 2 lists the sensitivity and specificity at several cut‐off points of Ct values used for generating the ROC curve. The tissue UHRF1 mRNA showed the highest accuracy at a Ct value of 31 with the maximum sensitivity and specificity of 87.5% and 82.1%, respectively, while circulating UHRF1 DNA gave the highest accuracy at a Ct value of 32 (2.49 × 106 copies/mL) with the maximum sensitivity and specificity of 79.2% and 76.2%, respectively. Although the tissue samples showed higher sensitivity and specificity than the plasma samples, the high sensitivity and specificity of circulating UHRF1 DNA indicated it could be an independent diagnostic biomarker of breast cancer.

Table 2.

Diagnostic relevance of ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1UHRF1 DNA level in tissue and plasma

| Tissue | Plasma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ct value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | C t value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| 33 | 54.2 | 91.1 | 33 | 62.5 | 81.4 |

| 32 | 70.8 | 83.9 | 32 | 79.2 | 76.2 |

| 31 | 87.5 | 82.1 | 31 | 83.3 | 71.4 |

| 30 | 89.3 | 72.4 | 30 | 86.5 | 60.7 |

Correlation UHRF1 DNA level in plasma with clinical outcome

The association between circulating UHRF1 DNA positivity and clinical factors was assessed in 229 breast cancer patients. The results of univariate analysis showed that the UHRF1 DNA level was not associated with age, menopause, tumor grade or histology grade, while high a UHRF1 DNA level was significantly associated with stage (P < 0.05) and lymph node metastasis (P < 0.05), as listed in Table 3, in which the positivity was defined as the sample with a Ct value less than or equal to 32. The results were similar to those of tissue UHRF1 mRNA when a Ct value of 31 was used as the cut‐off value. Analysis of the immunohistochemical data showed UHRF1 levels were not associated with estrogen receptor, P53, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor receptor or E‐cadherin (Table 3), while circulating UHRF1 DNA positivity was significantly associated with c‐erbB2‐positive status and progesterone receptor (PR)‐negative status (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Correlations of UHRF1 positivity in tissue and plasma with different clinical parameters

| Parameters | Patients | 62 tissues | 229 plasma samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | n (%) | P a | Total | n (%) | P a | ||

| Age | <50 years | 32 | 22 (68.7) | NS | 108 | 74 (67.2) | NS |

| ≥50 years | 30 | 18 (60.0) | 121 | 72 (58.0) | |||

| Menopausal | Premenopausal | 36 | 25 (69.4) | NS | 93 | 64 (67.4) | NS |

| Postmenopausal | 26 | 15 (57.7) | 136 | 82 (59.0) | |||

| Grade | I | 26 | 12 (46.2) | NS | 96 | 55 (56.7) | NS |

| II | 23 | 19 (82.6) | 86 | 71 (82.6) | |||

| III, IV | 13 | 9 (69.2) | 47 | 20 (39.2) | |||

| LNM | No | 29 | 15 (51.7) | 0.046 | 106 | 49 (45.8) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 33 | 25 (75.8) | 123 | 97 (76.4) | |||

| Cancer size | <2 cm | 16 | 11 (68.8) | NS | 78 | 51 (69.2) | NS |

| ≥2 cm | 46 | 29 (63.1) | 151 | 95 (60.9) | |||

| Histology grade | I | 13 | 9 (69.2) | NS | 94 | 49 (52.2) | 0.001 |

| II, III | 49 | 31 (63.3) | 135 | 105 (75.0) | |||

| Stage | Early | 26 | 12 (46.2) | 0.023 | 116 | 63 (61.0) | NS |

| Advanced | 36 | 28 (77.8) | 113 | 83 (71.6) | |||

| ER | Negative | 36 | 22 (61.1) | NS | 156 | 96 (61.1) | NS |

| Positive | 26 | 18 (69.2) | 73 | 50 (64.9) | |||

| PR | Negative | 44 | 25 (56.8) | NS | 90 | 42 (45.2) | 0.001 |

| Positive | 18 | 15 (83.3) | 139 | 104 (73.8) | |||

| c‐erbB2 | Negative | 18 | 8 (44.4) | 0.012 | 108 | 69 (63.3) | 0.04 |

| Positive | 44 | 32 (72.7) | 121 | 77 (61.6) | |||

| p53 | Negative | 29 | 19 (65.5) | NS | 39 | 26 (66.7) | NS |

| Positive | 33 | 21 (63.6) | 190 | 120 (62.1) | |||

| VEGF | Negative | 7 | 5 (71.4) | NS | 44 | 26 (59.1) | NS |

| Positive | 55 | 36 (65.5) | 185 | 120 (63.2) | |||

| EGFR | Negative | 12 | 10 (83.3) | NS | 87 | 57 (65.5) | NS |

| Positive | 50 | 30 (60.0) | 142 | 89 (60.5) | |||

| E‐cadherin | Negative | 19 | 12 (63.2) | NS | 108 | 74 (67.2) | NS |

| Positive | 43 | 28 (65.1) | 121 | 72 (58.0) | |||

Log‐rank test. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; Grade I, early stage; Grades II, III and IV, advanced stages; LNM, lymph node metastasis; NS, not significant; PR, progesterone receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

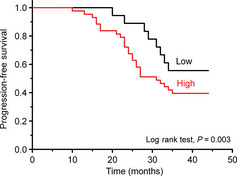

Kaplan–Meier plots and log rank test of progression‐free survival in 56 relapse or re‐examined patients were performed to determine the correlation of UHRF1 DNA level with the survival of patients. As shown in Figure 3, patients with high circulating UHRF1 DNA levels had significantly shorter progression‐free survival than patients with low circulating UHRF1 DNA levels (P = 0.003). In multivariate analysis, lymph node metastasis, cancer stage and UHRF1 level showed a correlation with poor survival (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for progression‐free survival based on high (n = 41) and low (n = 15) UHRF1 DNA levels in plasma. The P‐value was determined using the log rank test.

Table 4.

Results of multivariate analysis of independent prognostic factors in patients with breast cancer using Cox regression

| Factor | Progression‐free survival | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P a | |

| UHRF1 level | 0.26 (0.10–0.65) | 0.004 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.494 |

| Cancer size | 1.02 (0.51–2.04) | 0.963 |

| LNM | 3.68 (1.34–10.1) | 0.011 |

| Stage | 2.71 (1.06–6.96) | 0.038 |

| ER | 0.97 (0.48–1.97) | 0.941 |

| PR | 1.60 (0.79–3.25) | 0.189 |

Cox proportional hazard regression model. CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; LNM, lymph node metastasis; PR, progesterone receptor.

Discussion

Ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 has been found in various patients with cancers such as lung cancer,17 bladder cancer9 and breast cancers.18 It shows strong preferential binding to hemimethylated CG sites, the physiological substrate for DNMT1,19 which leads to the silencing of transposable elements.20 Ubiquitin‐like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 expression has recently been reported to be a general requirement in cancer cell proliferation and the functional determinant of growth regulation.21 Thus, UHRF1 is a possible marker for diagnosis and prognosis monitoring of breast cancer.

This work verifies that the breast cancer tissue from Chinese patients overexpresses UHRF1 compared with healthy individuals, and the UHRF1 DNA levels in plasma of patients are also higher than those of healthy controls. A high UHRF1 level is significantly associated with short progression‐free survival, thus UHRF1 might be an independent clinical prognostic marker of breast cancer.

The mean value of circulating DNA concentration (75.01 ng/mL) in plasma samples from patients with breast cancer is threefold higher than that of 23.55 ng/mL in healthy controls (P < 0.05). A similar finding has been reported by others in a larger case series.22, 23, 24 The circulating DNA in the plasma of cancer patients might reflect the overall cell heterogeneity of the tumor.25, 26, 27 Although the level of circulating DNA does not differ between the groups of patients, analysis of the circulating DNA in plasma can discriminate between cancer patients and healthy individuals, leading to the development of a valuable non‐invasive method for estimation of cancer and its prognosis.

In breast cancer patients, the circulating tumor‐specific DNA such as methylated RASSFIA DNA has been quantitatively analyzed for monitoring of adjuvant therapy.28 The clinicopathological correlations with mutations in the circulating p53 gene and aberrant methylation have also been reported.29 These results support the cancer origin of circulating DNA in breast cancer patients and the possibility of using molecular tests for its characterization.30 The current results show a significant difference of circulating UHRF1 DNA between patients and healthy controls and UHRF1 mRNA between cancer and tissues adjacent to the cancer. The ROC analysis shows good diagnostic accuracy using circulating UHRF1 DNA to discriminate breast cancer from healthy controls and UHRF1 mRNA to discriminate breast cancer tissues from tissues adjacent to the breast cancer, which demonstrates an association between UHRF1 level and breast malignancy. The maximum sensitivity and specificity of tissue UHRF1 mRNA (87.5% and 82.1%) are coincident with circulating UHRF1 DNA (79.2% and 76.2%), although the former is slightly better than the latter. The high sensitivity and specificity suggest that the UHRF1 gene might be an independent diagnostic biomarker for breast cancer. It is well known that RNA is very labile and easily degraded by ubiquitously present RNase. Moreover, obtaining the tissue samples is more difficult than the plasma samples. This work indicates that a high level of UHRF1 DNA in plasma is paralleled by a concomitant overexpression of mRNA and protein in cancer tissue. Circulating DNA reflects both tumor burden and dynamic states including proliferation, necrosis and apoptosis, which has been demonstrated by elevating the correlation between lactic dehydrogenase and DNA plasma levels in patients with lung cancer.31 Therefore, the detection of circulating UHRF1 DNA levels was more feasible to a diagnosis of breast malignancy than tissue UHRF1 mRNA.

The UHRF1 levels in a cohort of breast cancer patients show a powerful association with some clinical factors and outcomes. The patients in advanced stage, lymph node metastasis and c‐erbB2‐positive status show significantly high UHRF1 levels in both plasma and tissue. Here, early stage is the primary stage of carcinogenesis (grade I), and advanced stage is the development stage of carcinogenesis (grade II, III or IV). The results indicate that a high UHRF1 level is significantly associated with tumor development. The c‐erbB2 proto‐oncogene is a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Overexpression of c‐erbB2 has been associated with a worse prognosis in cancer patients.32 High UHRF1 levels in plasma are significantly associated with PR‐negative status and might be associated with triple‐negative (estrogen receptor negative, PR negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor‐2 not overexpressed) breast cancer. Triple‐negative breast cancer has distinct clinical and pathological features and generally shows a relatively poor prognosis and aggressive behavior.33 Thus, UHRF1 should be a useful prognostic biomarker of breast cancer patients.

The present study collected the plasma samples from 56 relapsed or refractory patients in the studied group. Among these 56 patients, 70% showed high UHRF1 DNA levels. The high UHRF1 levels have significant correlation with shorter progression‐free survival using a Kaplan–Meier analysis (P = 0.003). Such correlation is also found in other types of human cancer, such as lung and bladder cancer. Thus, a high UHRF1 level might be required for carcinogenesis and tumor progression. In comparison with the conclusion that plasma DNA concentration was not significantly associated with the survival of breast cancer patients, 27 the circulating UHRF1 DNA should be more sensitive than the total circulating DNA. Thus, detection of the UHRF1 DNA level in plasma might be useful as a prognostic tool in breast cancer patients.

The proposed results will require replication in additional independent and large cohorts. Further investigation of the interaction between UHRF1 level and breast cancer development will be carried out in our future studies.

In conclusion, our investigation demonstrates that UHRF1 exists in breast cancer tissues, and both breast cancer tissues and plasma from patients with breast cancer show the highly expressed UHRF1 gene, significantly different from tissues adjacent to the cancer and healthy controls. Thus, UHRF1 can be considered as a potential independent diagnostic and prognostic impact for breast cancer. The circulating UHRF1 DNA level shows high sensitivity and specificity for discriminating breast cancer from healthy controls. Detection of the circulating UHRF1 DNA level using real‐time quantitative PCR is a fast, easy and non‐invasive, leading to a promising application in predicting the outcome of breast cancer patients.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Basic Research Program (2010CB732400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21075055, 21135002, 21121091) and the Leading Medical Talents Program from the Department of Health of Jiangsu Province.

(Cancer Sci, doi: 10.1111/cas.12052, 2012)

References

- 1. Xu GW, Hu YS, Kan X. The preliminary report of breast cancer screening for 100000 women in China. China Cancer 2010; 19: 565–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weigelt B, Peterse JL, van't Veer LJ. Breast cancer metastasis: marker and models. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ et al Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature 2002; 415: 530–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ et al A gene‐expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Eng J Med 2002;347:1999–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim JK, Esteve PO, Jacobsen SE, Pradhan S. UHRF1 binds G9a and participates in p21transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37: 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bostick M, Kim JK, Estève PO, Clark A, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE. UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science 2007; 317: 1760–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Unoki M, Daigo Y, Koinuma J, Tsuchiya E, Hamamoto R, Nakamura Y. UHRF1 is a novel diagnostic marker of lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2010; 103: 217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jin W, Chen L, Chen Y et al UHRF1 is associated with epigenetic silencing of BRCA1 in sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 123: 359–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Unoki M, Kelly JD, Neal DE, Ponder BA, Nakamura Y, Hamamoto R. UHRF1 is a novel molecular marker for diagnosis and the prognosis of bladder cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jin W, Liu Y, Xu SG et al UHRF1 inhibits MDR1 gene transcription and sensitizes breast cancer cells to anticancer drugs. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 124: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gal S, Fidler C, Lo YM et al Quantitation of circulating DNA in the serum of breast cancer patients by real‐time PCR. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 1211–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang HW, Lee SA, Goodman SN et al Assessment of plasma DNA levels, allelic imbalance, and CA 125 as diagnostic tests for cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hohaus S, Giachelia M, Massini G et al Cell‐free circulating DNA in Hodgkin's and non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas. Ann Oncol 2009; 20: 1408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ren J, Li W, Yan L et al Expression of CIP2A in renal cell carcinomas correlates with tumour invasion, metastasis and patients' survival. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 1905–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gibson UE, Heid CA, Williams PM. A novel method for real time quantitative RT‐PCR. Genome Res 1996; 6: 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982; 143: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daskalos A, Oleksiewicz U, Filia A et al UHRF1‐mediated cancer suppressor gene inactivation in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2011; 117: 1027–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hashimoto H, Horton JR, Zhang X, Cheng X. UHRF1: a modular multi‐domain protein, regulates replication‐coupled crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone modifications. Epigenetics 2009; 4: 8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schaefer CB, Ooi SK, Bestor TH, Bourc'his D. Epigenetic decisions in mammalian germ cells. Science 2007; 316: 398–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature 2007; 447: 418–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jenkins Y, Markovtsov V, Lang W et al Critical role of the ubiquitin ligase activity of UHRF1, a nuclear ring finger protein, in cancer cell growth. Mol Biol Cell 2005; 16: 5621–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen X, Bonnefoi H, Diebold‐Berger S et al Detecting cancer‐related alterations in plasma or serum DNA of patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5: 2297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leung TN, Zhang J, Lau TK, Chan LY, Lo YM. Increased maternal plasma fetal DNA concentrations in women who eventually develop preeclampsia. Clin Chem 2001; 47: 137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sozzi G, Conte D, Mariani L et al Analysis of circulating tumor DNA at diagnosis and during follow‐up of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 4675–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lo YM, Tein MS, Lau TK et al Quantitative analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum: implications for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 768–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garcia JM, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Silva J, Bonilla F. Heterogeneous cancer clones as an explanation of discordance between plasma DNA and cancer DNA alterations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2001; 31: 300–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang ZH, Li LH, Hua D. Quantitative analysis of plasma circulating DNA at diagnosis and during follow‐up of breast cancer patients. Cancer Lett 2006; 243: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fiegl H, Millinger S, Mueller‐Holzner E et al Circulating cancer‐specific DNA: a marker for monitoring efficacy of adjuvant therapy in cancer patients. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 1141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silva JM, Dominguez G, Garcia JM et al Presence of tumor DNA in plasma of breast cancer patients: clinicopathological correlations. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 3251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Theodoropoulos PA, Polioudaki H, Agelaki S et al Circulating cancer cells with a putative stem cell phenotype in peripheral blood of patients with breast cancer. Cancer Lett 2010; 288: 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gautschi O, Bigosch C, Huegli B et al Circulating deoxyribonucleic acid as prognostic marker in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Houston SJ, Plunkett TA, Barnes DM, Smith P, Rubens RD, Miles DW. Overexpression of c‐erbB2 is an independent marker of resistance to endocrine therapy in advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1999; 79: 1220–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI et al Triple‐negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 4429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]