Abstract

Aims

Atrial fibrillation (AF) risk factors translate into disease progression. Whether this affects women and men differently is unclear. We aimed to investigate sex differences in risk factors, outcome, and quality of life (QoL) in permanent AF patients.

Methods and results

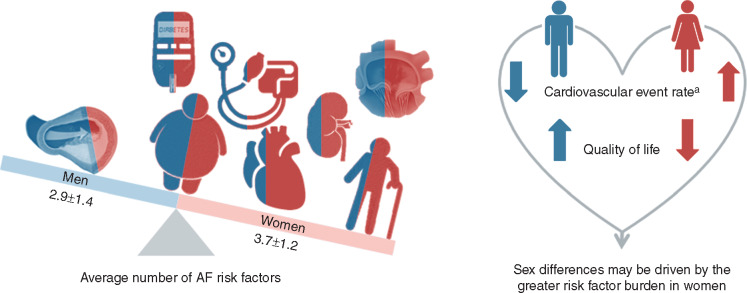

The Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation (RACE II) randomized 614 patients, 211 women and 403 men, to lenient or strict rate control. In this post hoc analysis risk factors, cardiovascular events during 3-year follow-up (cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization, stroke, systemic embolism, bleeding, and life-threatening arrhythmic events), outcome parameters, and QoL were compared between the sexes. Women were older (71 ± 7 vs. 66 ± 8 years, P < 0.001), had more hypertension (70 vs. 57%, P = 0.002), and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (36 vs. 17%, P < 0.001), but less coronary artery disease (13 vs. 21%, P = 0.02). Women had more risk factors (3.7 ± 1.2 vs. 2.9 ± 1.4, P < 0.001) Cardiovascular events occurred in 46 (22%) women and 59 (15%) men (P = 0.03). Women had a 1.52 times [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03–2.24] higher yearly cardiovascular event-rate [8.2% (6.0–10.9) vs. 5.4% (4.1–6.9), P = 0.03], but this was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of underlying risk factors. Women had reduced QoL, irrespective of age and heart rate but negatively influenced by their risk factors.

Conclusion

In this permanent AF population, women had more accumulation of AF risk factors than men. The observed higher cardiovascular event rate in women was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of risk factors. Further, QoL was negatively influenced by the higher number of risk factors in women. This suggests that sex differences may be driven by the greater risk factor burden in women.

Keywords: Sex differences, Permanent atrial fibrillation, Substrate, Predictors, Prognosis, Risk factors

What’s new?

Women with permanent atrial fibrillation (AF) had more accumulation of AF risk factors than men.

In women, a higher cardiovascular event rate was observed, this was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of risk factors. Quality of life was negatively influenced by the higher number of risk factors in women.

These findings support and extend previous findings and further underscore the evidence that women with AF show many differences in clinical presentation and outcome events compared to men.

Sex differences deserve attention, not in the least to characterize and determine their role so that our assessment and treatment of patients has a foundation that incorporates these differences if necessary.

Focusing on the underlying risk factor burden may provide a mechanical and biological basis to better understand the sex-related differences in the underlying substrate and associated cardiovascular risk in patients with AF.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a major health burden worldwide.1 Whilst women remain underrepresented in randomized clinical trials (RCTs), there has been an accumulation of evidence on sex-specific differences in incidence, prevalence, risk factors, presentation, and outcomes of patients with AF.2–4 Women are generally older, more often have hypertension, but less often have coronary heart disease.2–4 Risk factors may translate into AF development, in patients with metabolic syndrome a higher number of risk factors is associated with a stepwise increase in AF risk and poorer outcomes.4,5 Whether this affects women and men differently is unclear. Registry studies have reported a higher incidence of AF-related stroke and systemic thromboembolism specifically in older women.6,7 Increased mortality risk in women has also been described, but results are inconsistent.8,9 Furthermore, women with AF are generally more symptomatic, seek more care for symptoms, and report a lower quality of life (QoL).10 Questions on sex-specific differences in AF remain, and data on predictors of outcome is scarce to non-existent.

Gaps in knowledge on sex differences are undesirable since recognition of sex-based differences may offer an opportunity to improve personalized treatments. The aim of this Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent AF: A Comparison between Lenient vs. Strict Rate Control II (RACE II)11 post hoc analysis was to investigate sex-differences in risk factors, cardiovascular events and associated parameters, and QoL.

Methods

Study population

RACE II was a randomized, multicentre study comparing long-term effects of lenient vs. strict rate control in 614 patients with permanent AF performed in The Netherlands between January 2005 and June 2007. Eligibility criteria were: permanent AF for up to 12 months, age ≤80 years, mean resting heart rate >80 b.p.m., and current use of oral anticoagulation therapy [Vitamin K antagonists or aspirin, if no risk factors for thromboembolic complications were present according to European Society of Cardiology (ESC) AF guidelines at the time of inclusion].12 Previous stroke, but not transient ischemic attacks, was an exclusion criteria. Study design details have been described before.11 Patients randomized to lenient rate control had a resting heart rate target <110 b.p.m. Patients randomized to strict rate control had two heart rate targets: a resting heart rate target <80 b.p.m. and a heart rate target during moderate exercise <110 b.p.m. Patients were administered one or more negative dromotropic drugs until target(s) were reached. After achievement of rest and activity heart rate targets in the strict group, 24-h Holter monitoring was performed to check for bradycardia. Follow-up outpatient visits occurred every 2 weeks until heart rate target(s) were achieved (dose adjustment phase), and in all patients after 1, 2, and 3 years. Follow-up was terminated after 3 years or on 30 June 2009, whichever came first. The institutional review board of each participating hospital approved the study, and all patients provided written informed consent. For the present analysis, sex-differences in risk factors, cardiovascular events and associated parameters, as well as QoL were assessed.

Atrial fibrillation risk factors

Many risk factors are known to be associated with AF.2–4,12 In RACE II, extensive patient characteristics were collected and for each individual patient the number of AF risk factors was determined. Risk factors included: hypertension (1 point); heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (1 point); advanced age: >65 years (1 point); diabetes mellitus (1 point); coronary artery disease (CAD) (1 point); overweight or obesity: body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 (1 point); kidney dysfunction: estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73m2 (1 point); and moderate to severe mitral valve insufficiency (grade ≥2) (1 point) (Table 2). Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using MDRD formula: 175 × [serum creatinine (µmol/L) × 0.0113]−1.154 × age (years)−0.203 (×0.742 if female).

Table 2.

AF risk factors

| AF risk factors, n (%) | Overall | Women | Men | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 375 (61) | 147 (70) | 228 (57) | 0.002 |

| Heart failure | ||||

| HFrEF | 93 (15) | 25 (12) | 68 (17) | 0.10 |

| HFpEFa | 100 (23) | 52 (36) | 48 (17) | <0.001 |

| Advanced age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 65–74 | 258 (42) | 101 (48) | 157 (39) | |

| ≥75 | 155 (25) | 76 (36) | 79 (20) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 70 (11) | 30 (14) | 38 (9) | 0.08 |

| Coronary artery disease | 111 (18) | 28 (13) | 83 (21) | 0.02 |

| Obesity | 0.34 | |||

| BMI >25–30 kg/m2 | 289 (47) | 91 (43) | 198 (49) | |

| BMI >30 kg/m2 | 189 (31) | 68 (32) | 121 (30) | |

| Kidney dysfunction | 229 (37) | 110 (52) | 119 (30) | <0.001 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | ||||

| Mitral regurgitation | 110 (18) | 56 (27) | 54 (13) | <0.001 |

| Number of AF risk factorsb, mean ± SD | 3.2±1.4 | 3.7±1.2 | 2.9±1.4 | <0.001 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; SD, standard deviation.

N = 436 had data on all variables that compose HFpEF (146 women and 290 men).

For description see methods section: Atrial fibrillation risk factors.

Blood markers

After inclusion 10 mL blood was collected by vein puncture. Within 1 h the EDTA tube was centrifuged for 10 min, plasma was removed, and locally stored at −80°. After study completion NT-proBNP and hsTroponin-T measurements were performed using electrochemiluminisecent immunoassays (Roche Modular E170, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) at the core laboratory of the University Medical Center Groningen. Overall machine day-to-day variation was 2.0–2.2%.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography was performed at baseline in left lateral decubitus position. Images were obtained from parasternal (long- and short axis) and apical (two- and four-chamber) views. Atrial and ventricular dimensions and ejection fraction (LVEF) were quantified according to standard guideline recommendations. Left atrial volume was measured using the biplane Simpson method and indexed (LAVI) to the body surface area. Body surface area was calculated using the formula of DuBois and DuBois: (weight (kg)0.425 × height (cm)0.725) × 0.007184. Presence of HFrEF and HFpEF was determined using following respective definitions: HFrEF: LVEF < 40%; HFpEF: dyspnoea and/or fatigue, LVEF ≥ 40%, NT-proBNP >900pg/mL, and structural heart disease classified as LAVI ≥34 mL/m2 and/or left ventricular mass index ≥95 g/m2 in women and ≥115 g/m2 in men.13

Cardiovascular events

Cardiovascular events included cardiovascular death, hospitalization for heart failure, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or arrhythmic events, including syncope, sustained ventricular tachycardia, cardiac arrest, life-threatening adverse effects of rate-control drugs, and pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. Extensive definitions of individual composites have been previously described.11 Cardiovascular events that occurred between randomization and end of study were recorded. An endpoint adjudication committee, who were unaware of assigned treatment strategy, adjudicated endpoints. Minimal follow-up was 2 years; median follow-up was 3 years (interquartile range 2.2–3.1 years).

Quality of life

Baseline and end-of-study QoL was measured using three questionnaires. The Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) assessed General Health. SF-36, a validated general health survey that is frequently in arrhythmia studies, contains items to assess physical- and mental health. The survey is composed of eight subscales of multiple-choice questions, ranging in a stepwise fashion from impaired/low QoL to not impaired/high QoL. Subscales are transformed to a score ranging from 0 to 100, with lower scores representing a lower QoL. Severity of AF-related symptoms was assessed using the University of Toronto AF Severity Scale (AFSS), an instrument intended to measure perception of arrhythmia-related symptom severity. This 7-item questionnaire includes common AF symptoms (e.g. palpitations, dyspnoea). Items are rated on a 6-point scale. The final score ranges from 0 to 35, with a higher score indicating greater AF symptom severity. Severity of fatigue was measured using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 (MFI-20). MFI-20 contains 20 statements covering five domains of fatigue: general-, physical- and mental fatigue, and reduced activity and motivation. Scores range from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating more fatigue.

Statistical analysis

For the purpose of this post hoc analysis, the RACE II cohort population was stratified and analysed by sex. Baseline characteristics were compared between men and women. Variables are presented as numbers (percentage) or means (± standard deviation), as appropriate. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Comparisons between continuous variables were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or two-sample t-test depending on normality; comparisons between nominal variables were performed using the Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on expected cell sizes. Yearly event-rates were calculated by dividing the number of cardiovascular events by the number of follow-up years. Individual patient years were calculated as the time from randomization until the moment of censoring. Patients were censored if they withdrew informed consent, died, were lost to follow-up, had been followed through 30 June 2009, or had been in the trial for the maximum of 3 years. Differences in yearly event-rates were calculated by MedCalc (Windows version: 17.6). Cox regression analysis was performed to determine covariates associated to cardiovascular event occurrence for the total population and women and men specifically. Predefined univariate parameters with P < 0.1 and randomization strategy were tested in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model using a backward stepwise approach according to likelihood ratio. Final multivariable models included all covariates with P < 0.05 and randomization strategy to adjust for the post hoc nature of the current analysis. Final models were tested for first-line interactions. ANOVA was used to look for differences in QoL scores after adjusting for age, heart rate, and risk factors (since lower heart rates may reduce exercise capacity and induce fatigue).

Because of significant imbalances in baseline characteristics between women and men, we performed sensitivity analysis using propensity score matching in order to compare outcomes and QoL between matched women and men. Propensity scores were calculated for each patient using multivariable logistic regression based upon the following covariates: age, systolic blood pressure, BMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate, presence of diabetes, LVEF, NT-proBNP levels, and randomization strategy. Women and men were matched in a 1:1 ratio without replacement within 0.001 units of the propensity score.

All tests of significance were two-sided, with P-values of <0.05 assumed to indicate significance. All the analyses were considered to be exploratory. Analyses were generated by using SPSS version 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and atrial fibrillation risk factors

RACE II included 211 women and 403 men. Women were older (71 ± 7 vs. 66 ± 8, P < 0.001), 36% of women were ≥75 years compared to 20% of men. Women had more hypertension (70% vs. 57%, P = 0.002), HFpEF (36% vs. 17%, P < 0.001), and mitral valve regurgitation (27% vs. 13%, P < 0.001), but less CAD (13% vs. 21%, P = 0.02) (Tables 1 and2). Renal function was worse in women (eGFR 61 ± 16 mL/min/1.73 m2 vs. 68 ± 16 mL/min/1.73 m2, P < 0.001). This resulted in higher CHADS2 scores (1.6 ± 1.1 vs. 1.3 ± 1.0, P < 0.001) and more AF risk factors (3.7 ± 1.2 in women vs. 2.9 ± 1.4 in men, P < 0.001, Table 2, Figure 1). Left ventricular dimensions were smaller in women but baseline LAVI did not differ (Table 1). NT-proBNP levels were higher in women (1240 pg/mL vs. 879 pg/mL, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Overall (n = 614) | Women (n = 211) | Men (n = 403) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 68 ± 8 | 71 ± 7 | 66 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Total AF durationa (months), median (IQR) | 18 (6–60) | 18 (3–59) | 18 (5–60) | 0.90 |

| Duration AF episode at inclusion (months), median (IQR) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–7) | 3 (1–5) | 0.20 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiomyopathy | 41 (7) | 7 (3) | 34 (8) | 0.02 |

| Respiratory disease | 104 (17) | 31 (15) | 73 (18) | 0.31 |

| Previous hospitalization for heart failure | 60 (10) | 22 (10) | 38 (9) | 0.78 |

| Thromboembolic complication | 72 (12) | 29 (14) | 43 (11) | 0.29 |

| Physical examination, mean ± SD | ||||

| Length (cm) | 174 ± 9 | 166 ± 7 | 178 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 87 ± 17 | 79 ± 15 | 91 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.6 ± 4.6 | 28.7 ± 4.8 | 28.6 ± 4.4 | 0.94 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic | 136 ± 18 | 138 ± 18 | 135 ± 18 | 0.02 |

| Diastolic | 83 ± 11 | 84 ± 11 | 83 ± 11 | 0.18 |

| Heart rate in rest (b.p.m.) | 96 ± 12 | 96 ± 13 | 96 ± 12 | 0.97 |

| Clinical status | ||||

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Strict rate control | 303 (49) | 105 (50) | 198 (49) | 0.93 |

| Lenient rate control | 311 (51) | 106 (50) | 205 (51) | |

| CHADS2 score | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| 0 or 1, n (%) | 373 (61) | 107 (51) | 266 (66) | <0.001 |

| 2, n (%) | 159 (26) | 67 (32) | 92 (23) | 0.02 |

| 3–6, n (%) | 82 (13) | 37 (18) | 45 (11) | 0.03 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | 348 (57) | 147 (70) | 201 (50) | <0.001 |

| Palpitations | 145 (24) | 77 (37) | 68 (17) | 0.001 |

| Dyspnoea | 215 (35) | 94 (45) | 122 (30) | 0.54 |

| Fatigue | 183 (30) | 81 (38) | 102 (25) | 0.42 |

| Functional class (NYHA)—I/II/III (%) | 65/30/5 | 56/37/7 | 70/27/3 | 0.003 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 65 ± 16 | 61 ± 16 | 68 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Previous ECV, n, median (range) | 1 (0–22) | 1 (0–8) | 1 (0–22) | 0.57 |

| Rate control medication, n (%) | ||||

| No rate control drugs | 63 (10) | 10 (5) | 53 (13) | 0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 408 (66) | 154 (73) | 254 (63) | 0.02 |

| Verapamil or diltiazem | 90 (15) | 30 (14) | 60 (15) | 0.91 |

| Digoxin | 198 (32) | 94 (45) | 104 (26) | <0.001 |

| Other medication at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| ACE-inhibitors | 203 (33) | 68 (32) | 135 (34) | 0.79 |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 114 (19) | 48 (23) | 66 (16) | 0.06 |

| ACE-inhibitors and/or ARB | 306 (50) | 114 (54) | 192 (48) | 0.15 |

| Diuretics | 247 (40) | 104 (49) | 143 (36) | 0.001 |

| Statin | 177 (29) | 57 (27) | 120 (30) | 0.51 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 606 (99) | 209 (99) | 397 (99) | 0.72 |

| Laboratory values, median (IQR) | ||||

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1003 (634–1632) | 1240 (889–1907) | 879 (544–1408) | <0.001 |

| hsTroponin-T (pg/mL) | 9 (7–14) | 9 (6–13) | 9 (7–14) | 0.22 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| Left atrial end systolic volume (mL) | 73 ± 26 | 69 ± 23 | 75 ± 27 | 0.02 |

| Left atrial volume index (mL/m2) | 36 ± 12 | 37 ± 12 | 36 ± 12 | 0.30 |

| Right atrial length, apical view (mm) | 58 ± 8 | 57 ± 8 | 59 ± 8 | 0.01 |

| Left ventricular end diastolic dimension (mL) | 51 ± 7 | 48 ± 7 | 53 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular end systolic dimension (mL) | 36 ± 8 | 33 ± 8 | 38 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2) | 135 ± 44 | 123 ± 39 | 142 ± 45 | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 52 ± 12 | 54 ± 12 | 51 ± 12 | 0.002 |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ECV, electrical cardioversion; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

Total AF duration denotes the time from diagnosis of AF to start of study.

Figure 1.

Sex differences in risk factors. In the RACE II population, consisting of patients with permanent AF, women had more accumulation of AF risk factors than men. aThe observed higher cardiovascular event rate in women was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of risk factors. Further, QoL was negatively influenced by the higher number of risk factors in women. This suggests that sex differences may be driven by the greater risk factor burden in women. Colours in the left panel (men blue, women red) represent the distribution of risk factors in the RACE II population.

Rate control

Baseline heart rates were similar (Table 1). At baseline, women more frequently used rate control drugs (often digoxin, or digoxin in combination with a beta-blocker). This persisted through follow-up (Table 1, Supplementary material online, Table S1). After dose-adjustment, women in the lenient group used a higher dose of beta-blockers (all doses were normalized to metoprolol equivalent doses) compared to men (135 ± 84 mg vs. 112 ± 73 mg, P = 0.04). Women with both lenient and strict rate control used lower doses of digoxin compared to men (for lenient 169 ± 66 µg vs. 201 ± 81 µg, P = 0.034; for strict 189 ± 82 µg vs. 211 ± 83 µg, P = 0.04). This persisted till the end of follow-up. There were no sex differences in heart rate in the lenient and strict rate groups (Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

Cardiovascular events

During 3-year follow-up (interquartile range 2.2–3.1 years), 105 (17%) cardiovascular events occurred, 46 (22%) in women and 59 (15%) in men (Table 3). Yearly cardiovascular event-rate was 6.3%/year [95% confidence interval (CI) 5.2–7.7]. Women had a 1.52 (1.03–2.24) times higher yearly event-rate: 8.2%/year (95% CI 6.0–10.9) in women vs. 5.4%/year (95% CI 4.1–6.9) in men, P = 0.03. After adjusting for age it remained significant, P = 0.04. It was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of risk factors (P = 0.16). Additionally, in women and men no significant difference in primary outcome between lenient and strict rate control was observed, respectively P = 0.31 and P = 0.89. In the propensity-score matched cohort also no differences in outcome between women and men were observed (Supplementary material online, Tables S2 and S3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular events during follow-up

| Overall | Women | Men | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yearly cardiovascular event-rate (%) (95% CI) | 6.3 (5.2–7.7) | 8.2 (6.0–10.9) | 5.4 (4.1–6.9) | 0.03 |

| Total cardiovascular eventsa, n (%) | 105 (17.1) | 46 (21.8) | 59 (14.6) | 0.03 |

| Death from cardiovascular cause | 20 (3.3) | 9 (4.3) | 11 (2.7) | 0.34 |

| Cardiac arrhythmic death | 7 (1.1) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (0.7) | 0.24 |

| Cardiac non-arrhythmic death | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0.99 |

| Non-cardiac vascular death | 10 (1.6) | 4 (1.9) | 6 (1.5) | 0.74 |

| Heart failure hospitalization | 22 (3.6) | 9 (4.3) | 13 (3.2) | 0.50 |

| Stroke | 15 (2.4) | 5 (2.4) | 10 (2.5) | 0.99 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 11 (1.8) | 4 (1.9) | 7 (1.7) | 0.99 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.0) | 0.67 |

| Systemic embolism | 1 (0.2) | – | 1 (0.2) | 0.99 |

| Bleeding | 28 (4.6) | 14 (6.6) | 14 (3.5) | 0.10 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0.99 |

| Extracranial bleedingb | 25 (4.1) | 13 (6.2) | 12 (3.0) | 0.08 |

| Syncope | 6 (1.0) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (0.5) | 0.19 |

| Life-threatening adverse effects of rate control drugs | 5 (0.8) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | 0.35 |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation | 1 (0.2) | – | 1 (0.2) | 0.99 |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillation implantation | 1 (0.2) | – | 1 (0.2) | 0.99 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 6 (1.0) | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.0) | 0.99 |

CI, confidence interval.

Includes the total number of cardiovascular events that occurred during follow-up.

Extracranial bleeding events in women included: gastrointestinal (n = 4), post-surgery/intervention (n = 3), knee haematoma (n = 2), large haematoma upper leg after trauma (n = 3), retroperitoneal (n = 1). Extracranial bleeding events in men included: gastrointestinal (n = 5), post-surgery/intervention (n = 4), retroperitoneal bleeding (n = 1), urinary tract (n = 1), pulmonary related to bronchus carcinoma (n = 1).

Parameters associated with cardiovascular event occurrence

In multivariable analysis, AF duration [hazard ratio (HR) 1.01 per month (95% CI 1.00–1.01), P = 0.004), female sex [HR 1.87 (95% CI 1.15–3.03), P = 0.011], NT-proBNP [HR 1.03 per 100 (95% CI 1.01–1.04), P = 0.001], and hsTroponin-T [HR 1.02 per 1 (95% CI 1.01–1.04), P = 0.003] were associated with the occurrence of cardiovascular events in the total population (Table 4). In women, LAVI [HR 1.09 per 1 mL/m2 (95% CI 1.05–1.14), P < 0.001] and AF duration [HR 1.03 per month (95% CI 1.01–1.04), P < 0.001] were associated with outcome; in men, NT-proBNP [HR 1.08 per 100 (95% CI 1.03–1.13), P < 0.001] and hsTroponin-T [HR 1.09 per 1 (95% CI 1.04–1.13), P < 0.001]. There were interactions between LAVI and AF duration (P = 0.03) and NT-proBNP and hsTroponin-T (P = 0.02) in women and men, respectively.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses

| Overall |

Women |

Men |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Lenient rate controla | 0.84 (0.52–1.36) | 0.47 | 0.57 (0.26–1.25) | 0.16 | 1.00 (0.50–2.00) | 0.99 |

| Duration of AF per month | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.004 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <0.001 | ||

| Female sex | 1.87 (1.15–3.03) | 0.011 | ||||

| NT-proBNP per 100 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.001 | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | <0.001 | ||

| hsTroponin-T | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.003 | 1.09 (1.04–1.13) | <0.001 | ||

| LAVI (mL/m2) | 1.09 (1.05–1.14) | <0.001 | ||||

| Duration AF ⋅ LAVI | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.031 | ||||

| NT-proBNP hsTroponin-T | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.016 | ||||

AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAVI, left atrial volume index; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

Symptoms and quality of life

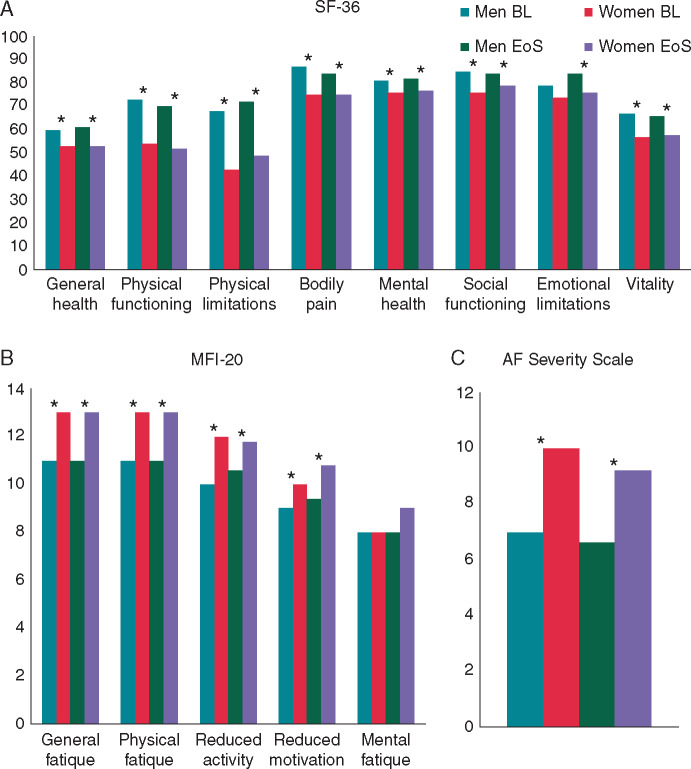

Women had more symptoms (70% vs. 50%, P < 0.001), Table 1). At the end of follow-up, 42% of men and 53% of women had symptoms (P = 0.004): dyspnoea (25% vs. 38%, P = 0.03), fatigue (20% vs. 31%, P = 0.15), and palpitations (5% vs. 20%, P < 0.001) were more frequent in women. Quality of life, as assessed with SF-36, MFI-20, and AFSS was significantly lower in women, also after correcting for heart rate, age, and number of risk factors (Figure 2). This remained unchanged during follow-up. Differences in physical functioning and fatigue scales were most pronounced. Emotional limitations (SF-36) and mental fatigue (MFI-20) did not differ between the sexes. Similar results were observed in the matched cohort (Supplementary material online, Table S4) The number of AF risk factors was associated with a reduced QoL, more clearly in women than in men, this suggests that women are more negatively affected, in terms of QoL, by permanent AF; per risk factor baseline SF-36 physical score decreased by 1.40 in women (95% CI −2.68 to −0.46) and by 1.21 in men (95% CI −1.90 to −0.54), both P < 0.05. This was also true for MFI-20 scales with the exception of mental fatigue. The number of risk factors was not a predictor for SF-36 mental scores or AFSS in both sexes.11

Figure 2.

Quality of life. Three quality of life (QoL) scores at baseline (BL) and end of study (EoS): (A) the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form questionnaire (SF-36), (B) the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), and (C) the Toronto AF Severity Scale (AFSS). SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores representing a lower QoL. MFI-20 scores range from 0 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater AF symptom severity. AFSS score ranges from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating more fatigue. *P-values <0.05 between the sexes.

Discussion

We show that men and women with permanent AF are not the same. Women were older, had more AF risk factors, and more frequently used rate control drugs. In women and men different parameters were associated with events. The observed higher cardiovascular event rate in women was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of risk factors. Further, QoL was negatively influenced by the higher number of risk factors in women. These results suggest that sex differences may be mainly driven by the presence of more risk factors in women

Patient characteristics and atrial fibrillation risk factors

In line with published data, we describe different patient characteristics in women and men.2–4 Women were older and more likely to have hypertension, HFpEF, poorer kidney function, and more mitral regurgitation. This may partially reflect the epidemiologically later age at AF onset in women and the fact that ageing allows the acquirement of more risk factors.2–4 Men had more often CAD.4

Risk factors play a prominent role in AF pathophysiology and sex may modulate how various risk factors contribute to AF.4,14 The prevalence of major risk factors have changed in both men and women during the years, and the population attributable risk of AF risk factors changed too.1,2 Atrial fibrillation risk factors translate into disease progression; a higher number of risk factors is associated with a stepwise increase in AF risk and AF progression including poorer outcomes in patients with metabolic syndrome.4,5 The specific pathophysiological mechanisms, however, remain incompletely studied. The presence of more risk factors in women, as demonstrated by our data, may explain the worse outcome and worse QoL observed.

Women more frequently used rate control drugs, specifically digoxin, or digoxin in combination with a beta-blocker. The Euro Observation Research Programme on Atrial Fibrillation (EORP-AF) survey also reported more digoxin use in women.2 Prescribed dosages of beta-blockade were higher in women receiving lenient rate control. Reasons are speculative, but greater symptom burden in women may prompt treating physicians to prescribe a higher dose. The higher rates of digoxin use may also reflect poorer tolerability and/or effect to commonly used rate-control medications. Additionally, women more often used a diuretic drug. To what extent sex differences in clinical profile and outcome reflect treatment disparities remains unknown.

Cardiovascular events

Women in RACE II experienced a higher cardiovascular event-rate. This was caused by a slightly higher, non-significant, occurrence of nearly all primary endpoint components. After adjustment for the number of underlying risk factors, however, the difference was no longer significant. In our cohort matched on sex and risk factors, we also observed no difference in outcome between women and men, further supporting the unmatched results. There have been longitudinal studies that reported higher mortality rates,8,9 and higher risk of stroke and thromboembolism in mostly older women, but results vary.6,7 Women in RACE II were on average 5 years younger than in the Framingham Original cohort, and follow-up was shorter.8 Additionally, RACE II patients were treated according to prevailing ESC AF guidelines at the time of inclusion,12 including oral anticoagulation in nearly all patients. This is contrary to studies that describe higher stroke and systemic embolisms rates in women.7 We observed a trend towards more extracranial bleeding events in women, conceivably explained by the fact that women had multiple risk factors associated with increased bleeding risk, including advanced age and kidney dysfunction.15

Parameters associated with cardiovascular event occurrence

We describe sex-specific parameters associated with cardiovascular event occurrence. In women, LAVI and duration of AF were associated with primary endpoint occurrence. This supports findings of AFFIRM that described female sex and mitral valve regurgitation being independently associated with left atrial enlargement,14 and left atrial enlargement being associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular death only in women.14 Left atrial enlargement is often an expression of risk factor and age-related degeneration due to haemodynamic changes in pressure- and volume load.16 Similarly, longer AF durations are associated with more severe remodelling, larger atria and worse outcome.4 Women included in RACE II had more AF risk factors, possibly partially explaining the link between LAVI and outcome. However, we cannot exclude a sex difference in atrial structural remodelling resulting in a more pronounced abnormal atrial milieu. Our findings confirm left atrial size as a marker in prognosis assessment of AF patients and underscore the clinical relevance of left atrial measurements.16 However, it should be noted that in AF patients visualization of the left atrium may be suboptimal and complicated by irregular contractions of the left atrial wall, limiting the reproducibility of left atrial parameters measures.

In men, NT-proBNP and hsTroponin-T were associated with primary endpoint occurrence, despite NT-proBNP levels being higher in women. It is known that women have higher NT-proBNP levels, regardless of menopause status or hormone therapy, and require higher cut-offs for optimal sensitivity and specificity in systolic dysfunction detection.17 The independent predictive value of hsTroponin-T and NT-proBNP for cardiovascular death and thromboembolic events in anticoagulated AF patients has been described in a substudy of the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial.18 NT-proBNP is a marker of atrial- and ventricular dysfunction.19 Origin of elevated hsTroponin-T in AF patients is not completely known, but may be due to mechanisms such as increased and irregular ventricular rate causing oxygen supply-demand mismatch and subsequent ischaemia, oxidative stress, and volume and pressure overload.19 The specific role of these blood biomarkers, which may reflect sex differences in cardiovascular pathophysiology, should be investigated further.

Quality of life

Studies indicate that women are more likely to experience symptoms and a worse QoL.10,20 We report that women experienced mainly physical limitations during follow-up; no differences in mental status were observed. Observed differences remained after correcting for age, heart rate, and risk factors. Additionally, in our matched cohort similar results were observed. Women continued to experience more severe physical limitations and reduced activity than men. Women more often used dual therapy (digoxin and beta-blocker) and higher dosages of beta-blocker. Higher dosages of beta blockade may result in more pronounced adverse effects, including fatigue, negatively affecting women’s physical ability.2 The number of AF risk factors was associated with a reduced QoL, more clearly in women than in men, this suggests that women are more negatively affected, in terms of QoL, by permanent AF.

Limitations and strengths

Present study is a post hoc analysis of RACE II and thus not specifically designed to study sex differences. Our data are restricted to observations and cannot reveal (causal) mechanisms. Therefore, the current study should be interpreted as hypothesis generating since the (pathophysiological)processes that underlie the observed sex differences remain elusive. Furthermore, there is an inherent baseline risk (factor) difference between men and women which is intertwined with the outcome difference observed. This may be bias in enrolment in the RACE II trial, actual population differences, or both. Therefore, current population may not be representative of a population-based sample. Additionally, we adjusted for randomization strategy in our analyses, but not for the high number of possible combinations of negative dromotropic drugs and dosages, as this would inappropriately complicate the analyses. The performed propensity score matching, albeit balancing covariates on average, also has it disadvantages. The matched cohort is smaller, the relative importance of covariates in their effects on outcome and QoL may differ, and unmeasured characteristics and confounders remain unbalanced. Nevertheless, these additional data support our main results.

Data on time in therapeutic range in patients receiving a vitamin K antagonist is missing, and the RACE 2 study was performed in the pre non-vitamin K oral anticoagulation (NOAC) era. Additionally, follow-up for cardiovascular events was limited to a relatively short follow-up of 3 years. These factors should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. Echocardiographic measurements were performed during AF, which may have influenced measurements, but this was the same for all patients. Blood markers represent one single-time point, but all patients were in stable condition and permanent AF at time of blood withdrawal. Studied risk factors were limited to those pre-specified, and therefore collected, in RACE II. Women were underrepresented in RACE II, as in many RCTs. Increasing female participation in RCTs will improve generalizability of trials and allow for effect modification by sex, which is essential to generate adequate evidence in women. Strengths include our well-characterized cohort, frequent follow-up, and data collection of events. An independent endpoint committee who were unaware of assigned treatment strategy adjudicated all endpoints.

Conclusions

Important sex differences exist in patients with permanent AF. Women were older, had more AF risk factors, and more frequently used rate control drugs. In women and men different parameters were associated with events. The observed higher cardiovascular event rate in women was no longer significant after adjusting for the number of risk factors. Further, QoL was negatively influenced by the higher number of risk factors in women. These findings highlight AF complexity and heterogeneity. More knowledge about sex-specific differences in AF risk and risk factors is essential to optimize cardiovascular care for both men and women.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support from the Dutch Heart Foundation (2003B118) and the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative: an initiative with support of the Dutch Heart Foundation, CVON 2014-9: Reappraisal of Atrial Fibrillation: interaction between hyperCoagulability, Electrical remodelling, and Vascular destabilization in the progression of AF (RACE V).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation 2014;129:837–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lip GY, Laroche C, Boriani G, Cimaglia P, Dan GA, Santini M. Sex-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Observational Research Programme Pilot survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Europace 2015;17:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linde C, Bongiorni MG, Birgersdotter-Green U, Curtis AB, Deisenhofer I, Furokawa T et al. Sex differences in cardiac arrhythmia: a consensus document of the European Heart Rhythm Association, endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2018;20(10):1565–1565ao. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lau DH, Nattel S, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Modifiable risk factors and atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2017;136:583–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chamberlain AM, Agarwal SK, Ambrose M, Folsom AR, Soliman EZ, Alonso A. syndrome and incidence of atrial fibrillation among blacks and whites in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J 2010;159:850–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang TJ, Massaro JM, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB et al. A risk score for predicting stroke or death in individuals with new-onset atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 2003;290:1049–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mikkelsen AP, Lindhardsen J, Lip GY, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C, Olesen JB. Female sex as a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:1745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998;98:946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Emdin CA, Wong CX, Hsiao AJ, Altman DG, Peters SA, Woodward M et al. Atrial fibrillation as risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in women compared with men: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2016;532:h7013.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piccini JP, Simon DN, Steinberg BA, Thomas L, Allen LA, Fonarow GC et al. Differences in clinical and functional outcomes of atrial fibrillation in women and men: two-year results from the ORBIT-AF registry. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: full text: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2006;8:651–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Proietti M, Raparelli V, Basili S, Olshansky B, Lip GY. Relation of female sex to left atrial diameter and cardiovascular death in atrial fibrillation: the AFFIRM trial. Int J Cardiol 2016;207:258–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace 2016;18:1609–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomas L, Abhayaratna WP. Left atrial reverse remodeling: mechanisms, evaluation, and clinical significance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinner MF, Stepas KA, Moser CB, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Sotoodehnia N et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein in the prediction of atrial fibrillation risk: the CHARGE-AF Consortium of community-based cohort studies. Europace 2014;16:1426–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hijazi Z, Oldgren J, Andersson U, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Hohnloser SH et al. Cardiac biomarkers are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in patients with atrial fibrillation: a Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) substudy. Circulation 2012;125:1605–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hijazi Z, Oldgren J, Siegbahn A, Granger CB, Wallentin L. Biomarkers in atrial fibrillation: a clinical review. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1475–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blum S, Muff C, Aeschbacher S, Ammann P, Erne P, Moschovitis G et al. Prospective assessment of sex-related differences in symptom status and health perception among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6(7). pii:e005401. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.005401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.