Abstract

What does the threat of and the policy response to the coronavirus pandemic mean for inter-group conflict worldwide? We examine time series trends for different types of conflict and evaluate discernible changes taking place as global awareness of COVID-19 spread. At the country level, we examine changes in trends following policy responses, such as lockdowns, curfews, or ceasefires. We specifically examine violent conflict events (e.g., battles, remote violence and bombings, and violence against civilians) as well as civil demonstrations (e.g., protests and riots) using data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project. Globally we see a relatively short-term decline in conflict, mostly driven by a sharp decrease in protest events, that has since recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Critical heterogeneity at the country level, however, persists. Finally, context-specific details challenge robust causal inference identifying the specific relationship between policy responses and conflict.

Keywords: COVID-19, Armed Conflict, Violence, Riots, Protests, Governance

1. Introduction

Over the course of just a few months, COVID-19 quickly spread across the world, with reported cases in nearly every country. In response, many governments enacted a variety of policy responses such as closing non-essential businesses and schools, promoting public safety campaigns, encouraging social distancing, or implementing some form of stay-at-home order. Despite concerns over growing inequality and the struggles of low-income households, such policies have helped “flatten the curve” in high-income and stable countries (Fowler, Hill, Levin, & Obradovich, 2020). Whether the benefits of such policies outweigh the costs in low- and middle-income countries, however, remains unclear (Mobarak, 2020).

The threat of COVID-19, and policy responses to this coronavirus, may influence life in low- and middle-income countries by impacting levels of inter-group conflict.1 Given the novelty of the COVID-19 global health risk, the relationship between the pandemic, policy responses, and inter-group conflict events in low- and middle-income countries remains poorly understood. Moreover, this relationship has serious implications for a host of development outcomes—such as food security, human rights, political expression, etc.

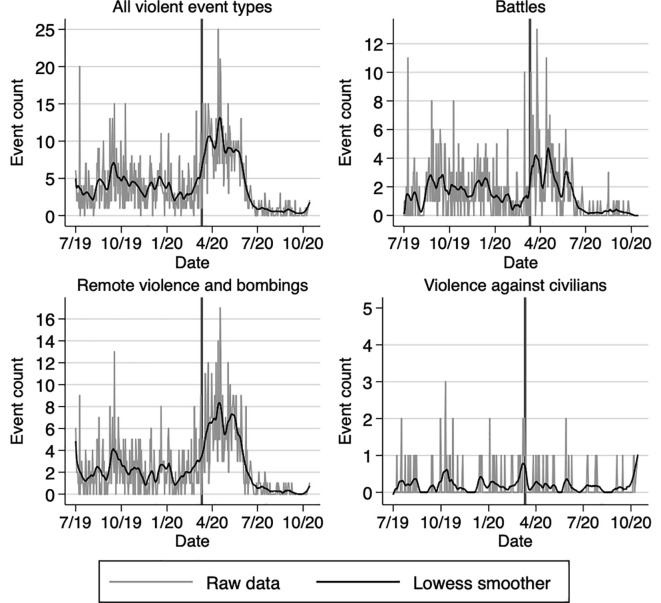

Overall, the threat of and policy response to COVID-19 appear to lead to a short-term reduction in conflict events. As displayed in Fig. 1 , the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) data show a notable drop in conflict event counts starting around early March, around the time the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11th (WHO, 2020).2 By late summer of 2020, daily inter-group conflict counts returned to their pre-March 2020 levels.

Fig. 1.

All conflict events by date, all ACLED countries (Source: Authors’ calculations using all conflict events recorded by ACLED from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. The vertical reference line is for March 11th, the day on which the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.).

Despite this general trend, critical heterogeneity is likely and the ex-ante relationship between COVID-19 health risks, policy responses, and conflict events remains ambiguous. Some relevant evidence suggests that the threat of and policy response to COVID-19 may lead to a reduction in local income levels and, in turn, a reduction in the opportunity cost of violence —thereby increasing conflict (Becker, 1968, Ehrlich, 1973, Hirshleifer, 1995, Collier and Hoeffler, 1998, Grossman, 1991, Fearon and Latin, 2003, Dube and Vargas, 2013, Bazzi and Blattman, 2014).3 Other relevant evidence suggests that the pandemic could lower the value of natural and physical resource exploitation and, in turn, reduce the economic benefit of seizing control of these resources (Reuveny and Maxwell, 2001, Grossman and Mendoza, 2003, Hodler, 2006, Besley and Persson, 2011, Caselli and Colleman, 2013). Furthermore, disruptions to global food supply chains may lead to increasing food prices (Koren & Winecoff, 2020), and in turn, increased conflict (Bellemare, 2014, Barrett, 2020).

Given the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are aware of only one other study that empirically investigates the relationship between COVID-19 and inter-group conflict events. Exploiting the differential timing of national COVID-19 responses across countries, Berman, Couttenier, Monnet, and Ticku, 2020 find evidence that national shutdowns reduce the probability of daily conflict by roughly 9 percentage points. We build on this work in two key ways: first, with a more modest analytical approach, we document critical heterogeneity in observed trends of inter-group conflict via country cases studies. Second, we discuss threats and challenges to common quasi-experimental empirical strategies used to estimate the causal relationship between COVID-19 and inter-group conflict.

The primary purpose of this study is to chronicle trends in conflict events during this historical moment. These findings are important to document for several reasons. First, conflict events are—by themselves—an important outcome. They represent expressions of social unrest and at times lead to fatalities. Second, exposure to conflict influences access to food, medicine, health care, work, travel, and other essential inputs for life (Adelaja & George, 2019). Finally, conflict can influence a host of development outcomes for years—if not decades—into the future (Abadie & Alberto, 2003).

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. We describe the data used for our study in Section 2 and report “global” trends in conflict events.4 In Section 3 we examine several country case studies that highlight critical heterogeneity and exceptions to the general trends shown in Section 2. We conclude in Section 4.

2. Data and “Global” trends

We use the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) for our analysis (Raleigh, Linke, Hegre, & Karlsen, 2010). ACLED is an event-level dataset that chronicles the location, date, and characteristics of a conflict occurrence. Geographic coverage for 2019 and early 2020 is extensive, with observations for countries throughout Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Unless otherwise noted, we show trends of daily conflict event counts from July 2019 through early-October 2020. These daily counts can be relatively noisy, so we also show a non-parametric local regression estimate of the trend over time.

We focus on two broad categories of events in ACLED and their five sub-categories.5 First, we examine violent events, including events associated with armed struggles over territory or acts of terror. The category includes battles, bombings, explosions, remote violence, and violence against civilians. Second, we look at demonstrations, including events in which citizens engage in collective action by protesting or rioting.6

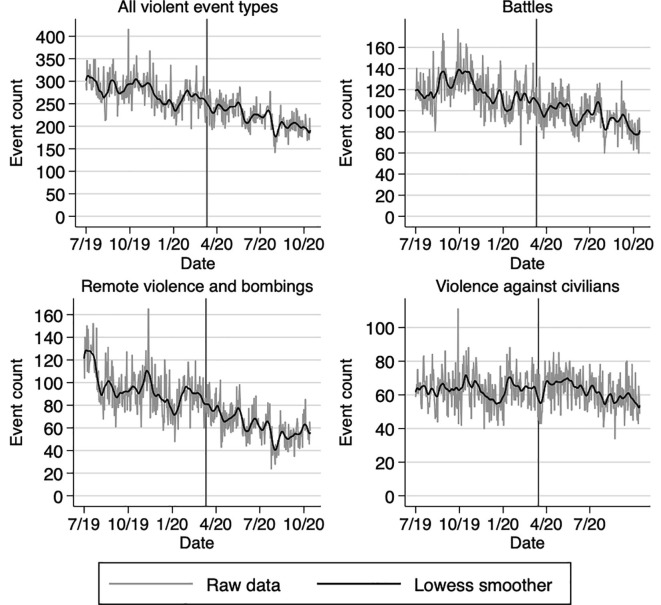

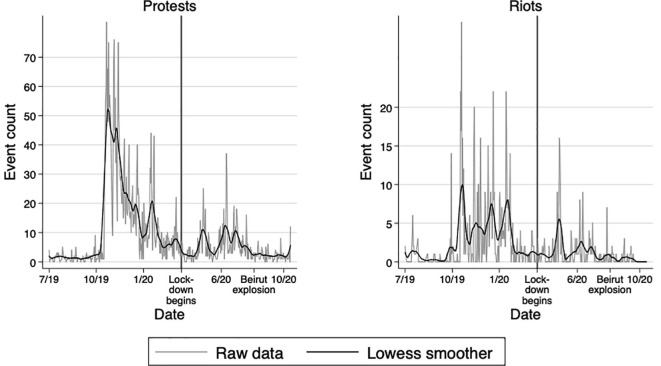

Fig. 2 displays the trend of all violent conflict event types in all ACLED countries. Battles, remote violence, and bombings appear to have been slowly declining since late 2019, and we do not see a sharp discontinuity in March 2020 indicating any response to higher awareness of the health threat. There is a small discontinuity in the trend of violence directed towards civilians, but it appears as though the global count rebounded in April 2020 and then declined only slightly through October 2020.

Fig. 2.

Violent events by date and event type, all ACLED countries (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. The vertical reference line is for March 11th, the day on which the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.).

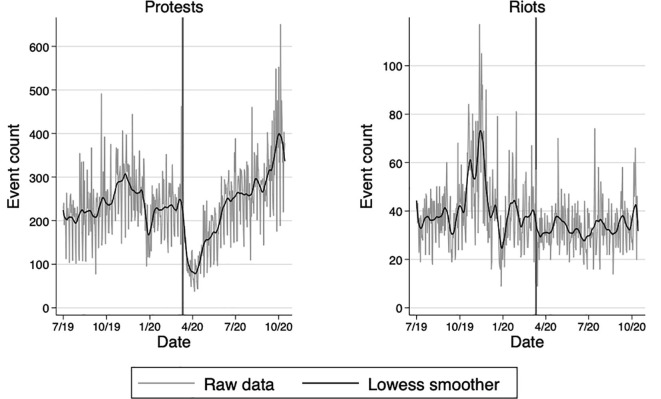

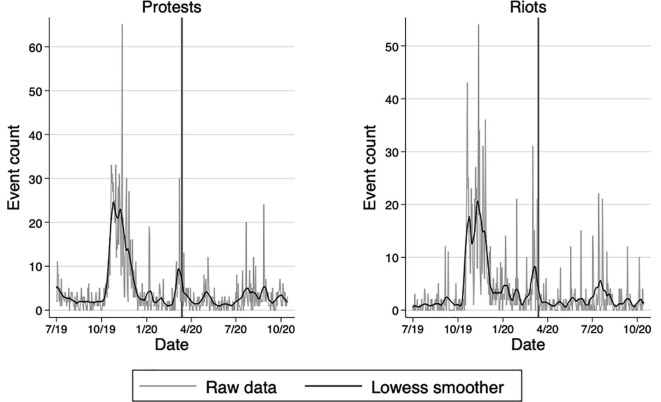

Fig. 3 displays the number of protest events and riots in all ACLED countries. We see a large drop in global protests in mid-May 2020. This sharp reduction in protesting may reflect both the higher costs of participating in protests as well as opposition movements deciding to postpone regular demonstrations.7 Shortly after this dramatic drop, the trend began to increase and eventually surpassed pre-March 2020 levels by October 2020. There is a small dip in riot events in mid-March, though it is difficult to distinguish this fluctuation from the underlying noise in the time-series. By late April 2020, we find an upward trend in global rioting, bringing daily counts roughly back to the same levels as in early 2020.

Fig. 3.

Demonstrations by date and event type, all ACLED countries (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. The vertical reference line is for March 11th, the day on which the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5. “All violent event types” aggregates the daily counts of battles, remote violence and bombings, and violence against civilians.).

Overall, the results may suggest that the threat of and policy response to COVID-19 have driven a reduction in conflict (Berman et al., 2020). We are, however, more interested in examining important heterogeneity in these trends across a variety of settings. As such, in the next section, we document details that complicate robust estimates of the causal effect of COVID-19, policy responses, and inter-group conflict.

We explore heterogeneity by performing a number of quantitative case studies that focus on specific country contexts. These quantitative case studies represent the majority of the remainder of this paper, with additional case studies included in the Supplemental Online Appendix. In the Appendix, we also report trends for “high conflict” countries based on whether a ceasefire was put into place in the spring of 2020.8

3. Quantitative case studies

In this section we perform five quantitative case studies focusing on India, Syria, Libya, Lebanon, and Chile. These five countries are not representative of the rest of the world, but they enrich our understanding of the complex relationship between contemporaneous political climate, pandemic risk, policy response, and inter-group conflict.

3.1. India

A country home to roughly 1.3 billion people, India implemented one of the world’s most strictly enforced national lockdowns on March 25, 2020. The swift and strict lockdown measures stranded millions of migrant workers in urban areas with little access to food or social support (Purnam, 2020). These competing dynamics provide a unique setting to consider when examining India’s national response to the pandemic and trends in various types of conflict events.

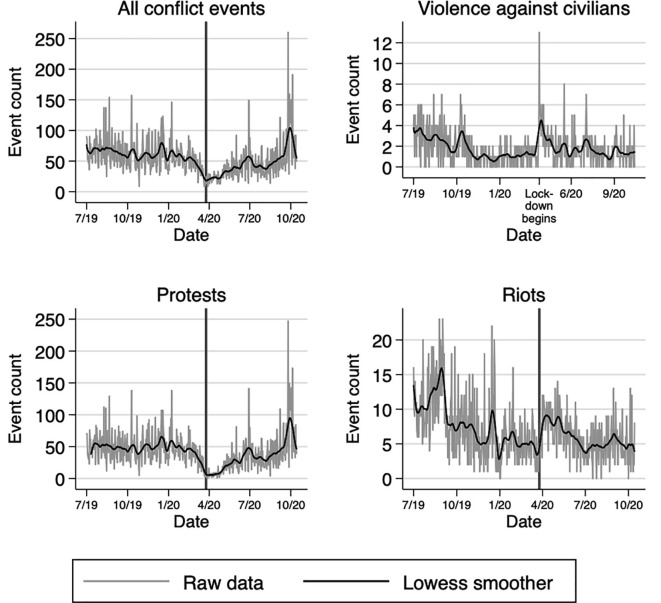

Fig. 4 displays trends of all types of conflict, violence against civilians, protests, and riots in India. When considering all conflict event types we see a noticeable decline in the number of events per day beginning in early 2020, and accelerating around the national lockdown implemented on March 25. Since then, conflict events per day have steadily increased in number and, by October 2020, have returned to pre-March 2020 levels.

Fig. 4.

Conflict events by date and type, India (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. India’s national lockdown, marked by a vertical line, began on March 25th. We omit this vertical line in the graph of violence against civilians to better visualize the dramatic spike on March 25th. The “any conflict event” category includes all 5 violent conflict and demonstration event types. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.)

It appears that the decline in all types of conflict can be mostly attributed to a similar drop in the number of protest events each day. Throughout the end of 2019 India experienced roughly 50 daily protest events on average. Protest events declined dramatically in March and April 2020 and, by October 2020, have rebounded by surpassing pre-March 2020 levels. This short-term fall in protest activity suggests that the net costs of participation in protesting rose in the immediate aftermath of India’s response to the pandemic. Even if the opportunity costs of participating are lower as workers lose livelihood opportunities (Campante and Chor, 2012, Campante and Chor, 2014), the pandemic risk, combined with the physical threat of violence by security forces punishing lockdown violators (Al Jazeera, 2020a), results in high costs to protest activity. Over time, however, it seems whatever factors discouraged protesting have subsided as, to date, protesting has more than returned to pre-March 2020 levels.

Although the trend is quite noisy, we do notice a sharp increase in the number of riots shortly following the beginning of India’s national lockdown. The trend in the number of riots per day has since declined and, by October 2020, has returned to levels similar to the months immediately proceeding the national lockdown. It is difficult to attribute this short-term increase in rioting to any particular issue or geographic location, but many of the riots appear to be related to migrant workers’ mobilizing violently in response to the loss of their livelihood options. Moreover, many of the riot events involved attacks on police.

Finally, we document a spike in violence against civilians on the same day that India implemented their national lockdown.9 This trend likely reflects the strict implementation of India’s national lockdown and supports news reports of Indian police using violence to penalize violators (Mukhopadhyay, 2020). By October 2020, the trend in violence against civilians has roughly returned to pre-lockdown levels.

Other countries, such as Uganda, also implemented strictly enforced policies. Fig. A5, in the Supplemental Online Appendix, documents trends in Uganda where the government strictly enforced a ban on public transportation and non-food markets. We see a noticeable, and relatively short-term, increase in all violent event types, specifically violence against civilians. We see a similar short-term spike in riots but no changes in the prevalence of protests.

3.2. Syria

In the tenth year of Syria’s civil war, the Syrian armed forces have established control over the majority of the country. Their current campaign targets the Idlib governorate, a large share of which is still held by rebel and Jihadist militias (BBC, 2019). On March 5th, Turkey and Russia, two countries directly involved in the Idlib fighting, negotiated a ceasefire agreement covering the Idlib governorate. To the best of our knowledge, this ceasefire was not motivated by COVID-19. There is currently no nation-wide agreement to lay down arms in response to COVID-19, hence we consider Syria to currently have a “partial” ceasefire in place.10

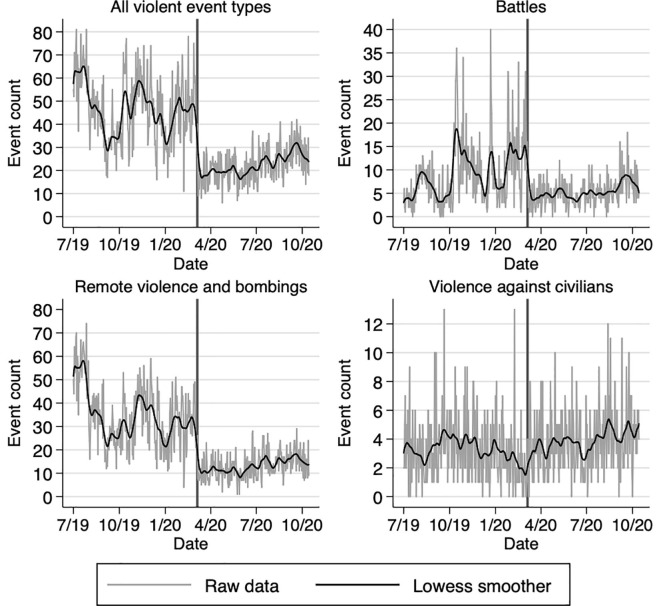

Perhaps because fighting has recently been concentrated in Idlib, we see a drastic reduction in battles, remote violence, and bombings for all of Syria since the ceasefire, as shown in Fig. 5 . By contrast, however, violence against civilians remains rather constant in the country, with an average of three to five events per day.11

Fig. 5.

Violent conflict events by date and event type, Syria (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. The vertical reference line is at March 6th, 2020, the first day of the ceasefire covering the Idlib governorate. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.)

Syria represents a large share of conflict events in the ACLED global data for our time period of interest. For all 2020 observations to date, 7% of battles, 25% of remote violence and bombings, and 6% of violent events against civilians took place in Syria. Hence, the downward trend in violent conflict for Syria likely has a direct influence on the global trendline (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is important that we note how difficult it is to disentangle attribution of the recent trends in Syria to either the Idlib ceasefire or COVID-19. This case study highlights the importance of careful identification of concurrent factors when deciphering changes in conflict trends in the COVID-19 era.

Other countries, such as Yemen, have also implemented a ceasefire in ongoing conflicts in the spring of 2020. In Fig. A6, shown in the Supplemental Online Appendix, we examine trends in Yemen where a COVID-19 motivated ceasefire seems to be associated with a reduction in violent conflict events in the short run. This trend appears to be mostly driven by a reduction in remote violence and bombings during the spring and early summer of 2020. But more recent data shows that the frequency of battles was on the rise in Yemen during the late summer. And like in Syria, there is very little change in the violence against civilians trend following the ceasefire agreement.

3.3. Libya

Since the 2011 forced removal of Muammar al-Qadaffi from Libyan leadership, the country has been mired in violent contestations over governance. Two competing governments have emerged in Libya, the internationally-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) and the Libyan National Army (LNA). While these two entities continue to fight over legitimacy, nonstate militant actors such as the Islamic State have also vied for territory and influence. Starting in 2019, the LNA has been on a campaign to seize the capital city of Tripoli and other strategic locations from the GNA. After launching the campaign, the GNA announced that it was deploying a counter-offensive strategy against the LNA (Zaptia, 2019). Although the UN brokered a truce betwen the LNA and GNA in January 2020, this ceasefire was gradually violated (UN Security Council, 2020a).12

Fig. 6 shows the violent conflict event time series for Libya. We see a small dip in violent conflict events following the truce established on January 12, 2020. The number of violent events, however, gradually increased through February and March, despite growing awareness of the risks of COVID-19.13 One problematic trend underlying the Libya data is the documented targeting of health facilities by the LNA. There have been several accounts of attacks on hospitals, including locations dedicated to treating those infected with COVID-19 (Al Jazeera, 2020b, Topcou, 2020, Al Jazeera, 2020c, Canli, 2020). These accounts highlight the fact that from the perspective of certain militant groups, the pandemic may introduce new vulnerabilities that can be exploited in their pursuit of territory and influence. Conflict frequency in Libya only began to subside after several GNA victories sent the LNA into retreat. At the time of writing, conflict frequency has fallen close to zero, and the two factions are working with the United Nations on a ceasefire agreement (UN, 2020).

Fig. 6.

Violent conflict events by date and event type, Libya (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to Oct. 14th, 2020. The vertical reference line is for March 11th, the day the WHO declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.).

As in the case of Libya, there is currently no ceasefire in Iraq (see Fig. A10) or Nigeria (see Fig. A9), two countries with active nonstate militias. In Nigeria, violent events were rising as northern states implemented lockdowns in the spring of 2020, though average daily counts have been gradually falling since late spring of 2020. For Iraq, upward trends in violent conflict since the country went into lockdown have been attributed to Islamic State activity. The terrorist organization expressed its plans to exploit Iraq’s vulnerability during the pandemic and increase its attacks (Al-Tamimi, 2020).

3.4. Lebanon

Protests erupted throughout Lebanon in October 2019 as civilians collectively denounced endemic government corruption and poor economic management. Although the Prime Minister stepped down in response to these protests, Lebanon’s complex political landscape and the relative strength of different sectarian-aligned interest groups has complicated progress towards building a new, transparent government. While the frequency of protests has fallen since October 2019, demonstrations continued through the end of 2019 and into 2020.

Fig. 7 shows the time series for protests and riots in Lebanon in 2019 and early 2020. It does not appear that the initial lockdown led to a fall in demonstration events: the number of protests and riots had already fallen relative to earlier months. And despite appeals to stay at home to prevent the spread of COVID-19, protesting resumed in late April and continued into May. Most analysts attribute the recent protests and riots to COVID-19 accelerating the country’s ongoing currency crisis (Economist, 2019).14 Fig. 7 also shows an increase in rioting shortly following the initial COVID-19 lockdowns. In these riots, participants have vandalized commercial banks throughout the country in an expression of frustration over their aforementioned financial woes (Azhari, 2019).

Fig. 7.

Demonstration events by date and type, Lebanon (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. The vertical reference line is for March 15th, the first day of Lebanon’s initial COVID-19 lockdown. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.)

The results from Lebanon suggest that in certain contexts, lockdown orders and the risk of contracting COVID-19 will not dissuade demonstrators from collectively showing their dissent. The opportunity cost of participation may seem relatively low for a “banked” Lebanese citizen whose savings are dramatically depreciating. For Lebanon’s poor and unbanked, the opportunity costs of participation are low as well, given COVID-19 related reductions in working hours as well as the declining value of their incomes.

On August 4th, 2020, an explosion at the Port of Beirut slammed the city, killing hundreds and causing billions of dollars in property damage (Reuters, 2020, Zeinab Hussein and Cohn, 2020). Analysts have determined that government negligence led to the explosion. But since this national disaster, there has been very little protesting or rioting, perhaps because survival needs are taking priority.

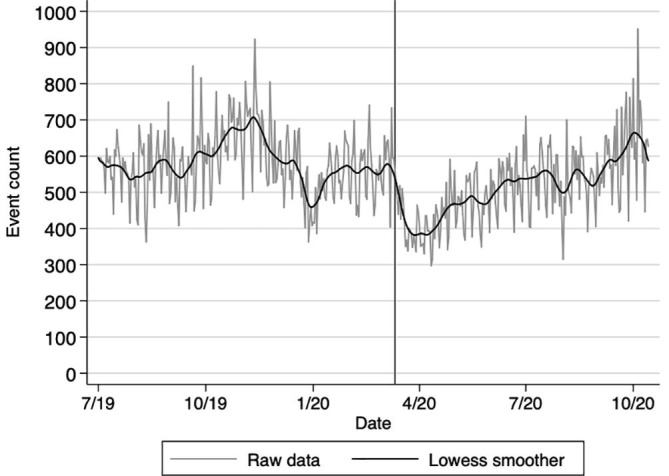

3.5. Chile

In response to rising public transportation fares and increasing economic inequality, Chile experienced a dramatic escalation in civil protests in 2019. These protests began as small demonstrations by students in Santiago, Chile’s capital city. By the middle of October 2019, however, demonstrations intensified as participants began vandalizing and seizing control of public infrastructure (McGowan, 2019). This escalation in both protests and riots can be seen clearly in Fig. 8 , with dramatic spikes—roughly 3 times baseline rates—of both types of events in October 2019.

Fig. 8.

Demonstration events by date and type, Chile (Source: Authors’ calculations using ACLED data from July 1st, 2019 to mid-May 2020. The vertical reference line is for March 13th, start of the government’s ban on public gatherings of more than 500 people. The Lowess smoother uses a bandwidth of 0.5.).

In early 2020, rates of both protest and riots began rising again. These demonstrations—still motivated by dramatic economic inequality—focused on university entrance exams, with students preventing access to test taking sites (Ramos & Natalia, 2020). On March 13, the Chilean government banned public gatherings of more than 500 people, which effectively paused all public demonstrations. Fig. 8 suggests this government policy influenced event trends. Daily counts of both protests and riots increased steadily, but abruptly decreased with the government’s ban. By October 2020 rates of both protests and riots have yet to reach levels observed in 2019.

We also see noticeable reductions in demonstration events in other countries. Despite reports of protests and riots in South Africa in response to widespread concerns of lack of food and hunger (Davis, 2002), Fig. A7 in the Supplemental Online Appendix, UN Security Council, 2020b shows a dramatic reduction in both protests and riots in the days preceding the national lockdown. However, daily counts of both protests and riots have since rebounded, indicating a potential lagged response to South Africa’s policy response. In Fig. A8, we also document a sharp decline in protests, but not riots, in Venezuela several days before the country’s national lockdown went into effect. The case of Venezuela also highlights a potential lagged response to the country’s policy response, with spikes in both protests and riots near the end of September 2020.

4. Conclusion

Our primary objective in this short paper is to document trends in conflict during the time of the coronavirus pandemic. We pay particular attention to the threat of and policy response to the pandemic and trends in inter-group conflict by performing quantitative case studies. Our analysis highlights the sensitive relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and inter-group conflict. Future work must consider the complex and localized realities motivating inter-group conflict around the world. Nevertheless, we offer three concluding thoughts.

First, across all ACLED countries there is a recognizable short-term decline in inter-group conflict events associated with COVID-19 (see Fig. 1). Additionally, this overall decline in inter-group conflict seems to be less due to any change in trends of violent events (see Fig. 2), and is mostly driven by a declining trend in protests (see Fig. 3). By October 2020, however, daily counts of inter-group conflict at the global level have returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Second, we document critical heterogeneity in observed trends in inter-group conflict events across various contexts amid increased awareness the coronavirus pandemic. The case studies highlight how some countries (e.g., India) may have a U-shaped protest trend over the initial months of the COVID-19 period. By contrast, countries facing multiple economic shocks over the period (e.g., Lebanon) exhibit diminishing protesting over time. In Syria, violent conflict has dramatically declined. By contrast, Libya witnessed increasing violent conflict in spring of 2020, and the trend only fell after successive victories by the GNA. In other contexts, there is very little noticeable change in the rate of inter-group conflict events despite the implementation of policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, robust causal inference identifying the specific relationship between policy responses and inter-group conflict will be relatively tricky. The specific details of our findings potentially threaten internal validity of quasi-experimental studies. In Syria, for example, the observed dramatic decline in violent conflict is associated with a partial ceasefire with unknown connections to COVID-19. In other cases, we see reductions in inter-group conflict events in the days preceding a national lockdown (see, South Africa in Fig. A7 and Venezuela in A8). Therefore, more ambitious empirical analysis employing quasi-experimental estimation strategies, such as Berman et al., 2020, should be interpreted with care (Goodman-Bacon & Marcus, 2020).

This is not to say that efforts to credibly estimate and understand the consequences of COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries are not worthwhile. To the contrary, future quasi-experimental work will do well to start small, so that authors can account for the complexity within a given context—accounting for details that we cannot go into detail in this short paper (e.g., centralization, timing, geographic implementation, etc. of policies). This future work could then build on the modest insights documented in our quantitative cases studies.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the constructive comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are ours and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or US Government determination or policy. This research was conducted prior to JRB’s employment with the USDA. All errors are our own.

Footnotes

Many express serious concern that COVID-19 may increase inter-personal conflict, such as the frequency of domestic violence (Peterman et al., 2020, Taub, 2020). Without diminishing the seriousness of those concerns, we focus exclusively on inter-group conflict in this paper.

The underlying components of this hypothesis are themselves ambiguous. Due to the health risk associated with social interaction amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the opportunity cost of violence and conflict may actually be higher now than before.

We enclose “global” in quotation marks because although the ACLED database does not cover all countries in the world, it does aim to provide information on the countries with the majority of the world’s inter-group conflict.

ACLED also includes an event category called “strategic developments,” which cover a broad variety of events, many of which do not directly involve violence for the associated date or location. With the exception of Fig. 1, we exclude any event categorized as a strategic development in ACLED.

Classifying an event as a protest or a riot is not straightforward, as one demonstration could have attributes of both. In the ACLED dataset, a demonstration is labeled as a “protest” if participants are engaging in peaceful collective action, including cases with documented violence against protesters. See ACLED, 2019. “Riots” cover all manifestations in which participants are engaging in violence, including “mob violence,” and the destruction of property.

For example, Algeria’s Al-Hirak movement has been organizing regular protests since 2019. Al-Hirak initially postponed its protests in response to COVID-19, leading to a decline in protesting to essentially zero during the rest of the spring of 2020. During the summer, protesting resumed (See BBC, 2020 and Fig. A11).

Some of these ceasefires were COVID-19 motivated, while others emerged prior to the global recognition of the threat of the new coronavirus. See the Supplemental Appendix for discussion of the countries studied and the respective ceasefire statuses.

This spike is so dramatic it prevents us from visualizing the lockdown start date with a vertical line in the figure.

It is unclear how much longer this ceasefire will last. A Russian air strike targeted Idlib in October of 2020, and this attack puts the Russia-Turkey brokered ceasefire at risk (BBC, 2020)

The ACLED data suggests that a variety of actors have been involved in this violence. As of October 14th, 2020, ACLED counts 862 conflict events classified as “violence against civilians” for Syria in 2020. For 43% of the observations, the ACLED study team was unable to attribute the event to a particular group. About 10% of these events were carried out by the Syrian military: these were mostly deaths by torture in prison. ACLED attributes 20% of violence against civilians to the Syrian Democratic Forces, a Kurdish-led coalition allied with the United States. The majority of cases in ACLED in which the SDF is the perpetrator involve arbitrary arrests and kidnappings. A handful of these arrests were in response to COVID-19 curfew violations. Numerous different non-state groups, including communal militias, rebel groups, Turkish forces, and Jihadist militias, carried out the remaining violence against civilian events, according to ACLED.

In April 2020, the LNA called for a COVID-19 motivated ceasefire, but the GNA refused their offer, claiming they do not trust the LNA to uphold such an agreement (Wintour, 2020).

The overwhelming majority of 2020 violent conflict events for Libya in the ACLED data involved the GNA and LNA. Looking at all battles in Libya between January 1st, 2020 and the date of writing, 52% are associated with the LNA and 39% with the GNA. The LNA was also responsible for 55% of remote violence and bombings over this time interval, while the GNA was involved in 20%.

For over twenty years, the Lebanese Central Bank has pegged the Lebanese Pound to the US Dollar (at a rate of roughly 1,500 LBP to 1 USD) by buying dollars from commercial banks at above-market value. This approach to currency management has been likened to a pyramid or Ponzi scheme, as it relies heavily on continuous cash inflow via commercial banks (Economist, 2020, Economist, 2019). But as deposits to commercial banks fell in 2019, these banks became increasingly illiquid. And the reduction of cash inflows negatively impacted the central government’s ability to purchase US dollars. Shortly before the country’s COVID-19 response shuttered businesses, the government defaulted on a $1.2 billion Eurobond. This is the first time in Lebanon’s history that the country defaulted on a debt (Economist, 2020). Further reductions in the purchasing power of the Lebanese pound, and pandemic-driven shifts in supply and demand, have left many citizens struggling to afford basic necessities (Economist, 2020). Because of illiquidity in the banking sector, Lebanese citizens with bank accounts cannot simply withdrawal their savings as USD and instead are watching their wealth depreciate.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, athttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105294.

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abadie Alberto, Gardeazabal Javier. The economic cost of conflict: A case study of the basque country. American Economic Review. 2003;93(1):113–132. [Google Scholar]

- ACLED (2019). “Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) Codebook.”

- Adelaja A., George J. Effects of conflict on agriculture: Evidence from the Boko Haram insurgency. World Development. 2019;117:184–195. [Google Scholar]

- Al Jazeera (2020a). “Indian police use force against coronavirus lockdown offenders.” Al Jazeera.

- Al Jazeera Libya: Tripoli hospital attacked by “Haftar”s missles. Al Jazeera. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Al Jazeera (2020c). “Libyan hospital treating coronavirus patients attacked.” Al Jazeera.

- Al-Tamimi A.J. Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi’s Blog; 2020. Islamic state editorial on the coronavirus pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Azhari T. Banks targeted in Lebanon’s ‘night of the Molotov. Al Jazeera. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Barrett C.B. Actions now can curb food systems fallout from COVID-19. Nauter Food. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi S., Blattman C. Economic shocks and conflict: Evidence from commodity prices. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 2014;6(4):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- BBC Syria war: Alarm after 33 Turkish soldiers killed in attack in Idlib. BBC News. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- BBC In a first, Algerians stay home instead of protesting. BBC Monitoring Middle East. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- BBC Syria war: ‘Russian air strikes kill dozens’ in Idlib. BBC News. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Becker G.S. Palgrave MacMillan; 1968. The economic dimensions of crime. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare M. Rising food prices, food price volatility, and social unrest. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Besley T., Persson T. The logic of political violence. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2011;126(3):1411–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Campante F.R., Chor D. Why was the Arab world poised for revolution? Schooling, economic opportunities, and the Arab Spring. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2012;26(2):167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Campante F.R., Chor D. The people want the fall of the regime’: Schooling, political protest, and the economy. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2014;42(3):495–517. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, N., Couttenier, M., Monnet, N., Ticku, R. (2020). Shutdown policies and worldwide conflict. ESI Working Paper (20-06). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Canli E. Libya: Haftar militias strike hospital in Tripoli. Anadolu Agency; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli F., Colleman W. On the theory of ethnic conflict. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2013;11:161–192. [Google Scholar]

- Collier P., Hoeffler A. On economic causes of civil war. Oxford Economic Papers. 1998;50(4):563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R. (2002). The biggest lockdown thread: Hunger, hunger everywhere. Daily Maverick, April 16, 2020.

- Dube O., Vargas J.F. Commodity price shocks and civil conflict: Evidence from Colombia. Review of Economic Studies. 2013;80(3):1384–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I. Participation in illegitimate activities: A theoretical and empirical investigation. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81(3):521–565. [Google Scholar]

- Fearon J.D., Latin D. Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review. 2003;97(1):75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, J. H., Hill, S. J., Levin, R., Obradovich, N. (2020). The Effect of Stay-at-Home Orders on COVID-19 Infections in the United States. Working Paper.

- Goodman-Bacon, A., and Marcus, J. (2020). Using Difference-in-Differences to Identify Causal Effects of COVID-19 Policies. Working Paper.

- Grossman H. A general equilibrium model of insurrections. American Economic Review. 1991;81(4):912–921. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman H., Mendoza J. Scarcity and appropriative competition. European Journal of Political Economy. 2003;19(4):747–758. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer J. Anarchy and its breakdown. Journal of Political Economy. 1995;103(1):26–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hodler R. The curse of natural resources in fractionalized countries. European Economic Review. 2006;56(6):1367–1386. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan C. Chile protest: What prompted the unrest? Al Jazeera. October. 2019;30:2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mobarak A.M. Responding to COVID-19 in the Developing World. Yale Insights; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, A. (2020). India: Police under fire for using violence to enforce coronavirus lockdown. DW Akademie, March 28, 2020.

- Peterman, A., Potts, A., O’Donnell, M., Thompson, K., Shah, N., Oertelt-Prigione, S., van Gelder, N. (2020). Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children. Center for Global Development Working Paper (528).

- Purnam, E. (2020). India’s migrant workers protest against lockdown extension. Al Jazeera, April 15, 2020.

- Koren O., Winecoff W.K. Food Price Spikes and Social Unrest: The Dark Side of the Fed’s Crisis-Fighting. Foreign Policy, May. 2020;20:2020. [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh C., Linke A., Hegre H., Karlsen J. Introducing ACLED: An armed conflict location and event dataset. Journal of Peace Research. 2010;47(5):651–660. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M., Natalia, A. (2020). Chilean university admissions tests hit by fresh protests. Reuters, January 6, 2020.

- Reuveny R., Maxwell J. Conflict and renewable resources. Journal of Conflict Research. 2001;45(6):719–742. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters. (2020). Beirut port blast death toll rises to 190. Reuters.

- Taub A. A New Covid-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide. The New York Times; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist Broke in Beirut: A long=feared currency crisis has begun to bite in Lebanon. The Economist. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- The Economist From crisis to crisis: Why protestors firebomb banks in Lebanon. The Economist. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- The Economist Resilient no more: For the first time, Lebanon defaults on its debts. The Economist. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Topcou G. Haftar militias attack field hospital in Libyan capital. Anadolu Agency. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- UN . UN salutes new Libya ceasefire agreement that points to ‘a better and more peaceful future’. UN News; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN Security Council . United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General. United Nations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN Security Council . United Nations; 2020. Update on the Secretary General’s Appeal for a Global Ceasefire. [Google Scholar]

- Wintour P. Tripoli government rejects rebel general’s ceasefire offer in Libya. The Guardian. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020). “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), Situation Report—67.” Data as reported by national authorities by 10:00 CET 27 March 2020.

- Zaptia, S. (2019). “Serraj GNA launches ‘Volcano of rage’ anti-Hafter operation to defend Tripoli”. Libya Herald.

- Zeinab Hussein, N., Cohn, C. (2020). “Insured losses from Beirut blast seen around $3 billion: sources.” Reuters.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.