Diamines are important monomers for polyamide plastics; they include 1,3-diaminopropane, 1,4-diaminobutane, 1,5-diaminopentane, and 1,6-diaminohexane, among others. With increasing attention on environmental problems and green sustainable development, utilizing renewable raw materials for the synthesis of diamines is crucial for the establishment of a sustainable plastics industry. Recently, high-performance microbial factories, such as Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum, have been widely used in the production of diamines.

KEYWORDS: diamines, biosynthesis, nylon, metabolic engineering

ABSTRACT

Diamines are important monomers for polyamide plastics; they include 1,3-diaminopropane, 1,4-diaminobutane, 1,5-diaminopentane, and 1,6-diaminohexane, among others. With increasing attention on environmental problems and green sustainable development, utilizing renewable raw materials for the synthesis of diamines is crucial for the establishment of a sustainable plastics industry. Recently, high-performance microbial factories, such as Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum, have been widely used in the production of diamines. In particular, several synthetic pathways of 1,6-diaminohexane have been proposed based on glutamate or adipic acid. Here, we reviewed approaches for the biosynthesis of diamines, including metabolic engineering and biocatalysis, and the application of bio-based diamines in nylon materials. The related challenges and opportunities in the development of renewable bio-based diamines and nylon materials are also discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Diamines are a class of cationic molecules consisting of a saturated carbon backbone and two amine groups (1). Examples include 1,3-diaminopropane, 1,4-diaminobutane (putrescine), 1,5-diaminopentane (cadaverine), 1,6-diaminohexane (hexamethylenediamine), and other long-chain diamines with carbon skeletons of differing length. Diamines are abundant in nature and play an important role in the physiology of many organisms (1). For instance, diamines are used as phytohormones in plants, as stabilizers for many anionic substances, such as DNA and phospholipids due to their cationic properties, and as modulators of various transport ion channels (2). Some studies have proposed that diamines may be important components of cell membranes in Gram-negative bacteria in which they regulate pH homeostasis of the cell (3, 4), and they may also be related to cell differentiation as signaling factors (5). In industry, diamines are platform chemicals with important applications. They can be used to synthesize pesticides, metal ion chelating agents, surfactants, and additives for motor oils and fuels (6). Diamines are monomers used to synthesize polyamides, the most widespread plastics in daily life, by condensing with dicarboxylic acids (7).

At present, most diamines are produced by chemical refining methods based on nonrenewable petroleum resources (8, 9). As increasing attention has been paid to resource depletion, climate change, environmental pollution, and sustainable development issues, the biological production of diamines from renewable raw materials has become a more preferred alternative route for achieving sustainable development of the economy and environment. Furthermore, with the proposed banning of disposable plastic products by the European Commission, the development of bio-based plastics is becoming increasingly urgent (10). The development of diamine biosynthesis technology will effectively accelerate the development of bio-based polyamides.

In recent years, with the development of tools and strategies related to systems metabolic engineering, developing strains to produce diamines has become more and more effective (11). Recent studies on diamine biosynthesis are reviewed here, including metabolic engineering and biocatalysis (1, 12, 13), and some important production data are summarized in Table 1. Moreover, research on bio-based nylon and challenges in the development of diamine biosynthesis provide a valuable reference for the establishment of entirely new bio-based nylon production systems.

TABLE 1.

Biosynthesis of diamines in engineered microorganismsa

| Target product | Host strain | Carbon source | Engineering information | Titer (g/liter) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/liter/h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Diaminopropane | E. coli | Glucose | W3110 ΔlacI thrAC1034T lysCC1055T Pppc::Ptrc PaspC::Ptrc ΔpfkA (p15DDoptppc) | 12.8 | N | 0.13 | 15 |

| W3110 ΔlacI thrAC1034T lysCC1055T Pppc::Ptrc PaspC::Ptrc ΔpfkA (p15DDopt aspC) | 13.1 | N | 0.19 | 15 | |||

| Putrescine | E. coli | Glucose | XQ52-p15SpeC: WL3110 ΔspeE ΔspeG ΔargI ΔpuuPA PargECBH::Ptrc PspeF-potE::Ptrc PargD::Ptrc PspeC::Ptrc ΔrpoS (p15SpeC) | 24.2 | N | 0.75 | 27 |

| Based on XQ52-p15SpeC (27) Downregulation of argF and glnA:112SargF pKK105SglnA | 42.3 | 0.26 | 1.27 | 28 | |||

| C. glutamicum | Glucose | C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 ΔargR ΔargF odhATTG ΔsnaA pVWEx1-speC-gapA-pyc-argBA49V/M54V-argF21 | 5.1 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 31 | |

| C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 ΔargR ΔargF pVWEx1-speC-5‘21-argF | 9.0 | 0.16 | 0.55 | 29 | |||

| C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 ΔargF ΔproB ΔspeE ΔargR Δpuo ΔfabG::PH36-speC1ECL ΔbutA ΔsnaA ΔodhA pEC-pyc458 | 11.1 | 0.29 | N | 32 | |||

| M. alcaliphilum | Methane | M. alcaliphilum 20Z Δldh Δack ΔspeE1::argDJ pAWP89-speCtac | 0.1 | 0.03 | N | 38 | |

| 1,5-Diaminopentane | E. coli | Glucose | W3110 ΔlacI ΔspeE ΔspeG ΔygjG ΔpuuPA PdapA::Ptrc pTac15K-CadA; downregulation of murE | 12.6 | N | N | 43 |

| C. glutamicum | Glucose | DAP-3c: C. glutamicum 11424 PsodlysC311 PsoddapB 2× ddh 2× lysA Δpepck, hom59 PsodpycA458 PtufldcCopt Psod2893 | N | 0.14 | N | 48 | |

| Based on C. glutamicum LYS-12 (85): PtufldcCopt ΔbioD ΔNCgl1469 ΔlysE Psodcg2893 | 88.0 | 0.29 | 2.20 | 49 | |||

| C. glutamicum PKC PlysE:: PH30ldcC | 103.8 | N | N | 53 | |||

| Xylose | DAP-3c: pClik5a MCS PgroXyl Psodtkt Peftufbp icdGTG Δact ΔlysE | 103.0 | 0.04 | N | 51 | ||

| B. methanolicus | Methanol | MGA3 (pTH1mp-cadA) | 11.3 | N | N | 52 |

N, data not provided in the literature.

THE NATURAL SYNTHETIC PATHWAYS OF DIAMINES IN MICROORGANISMS

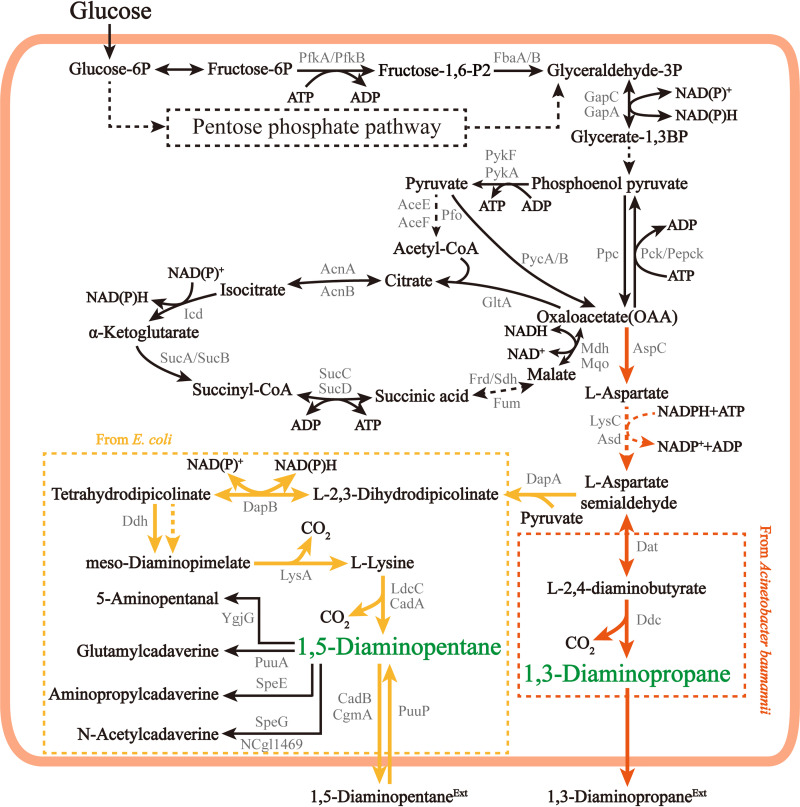

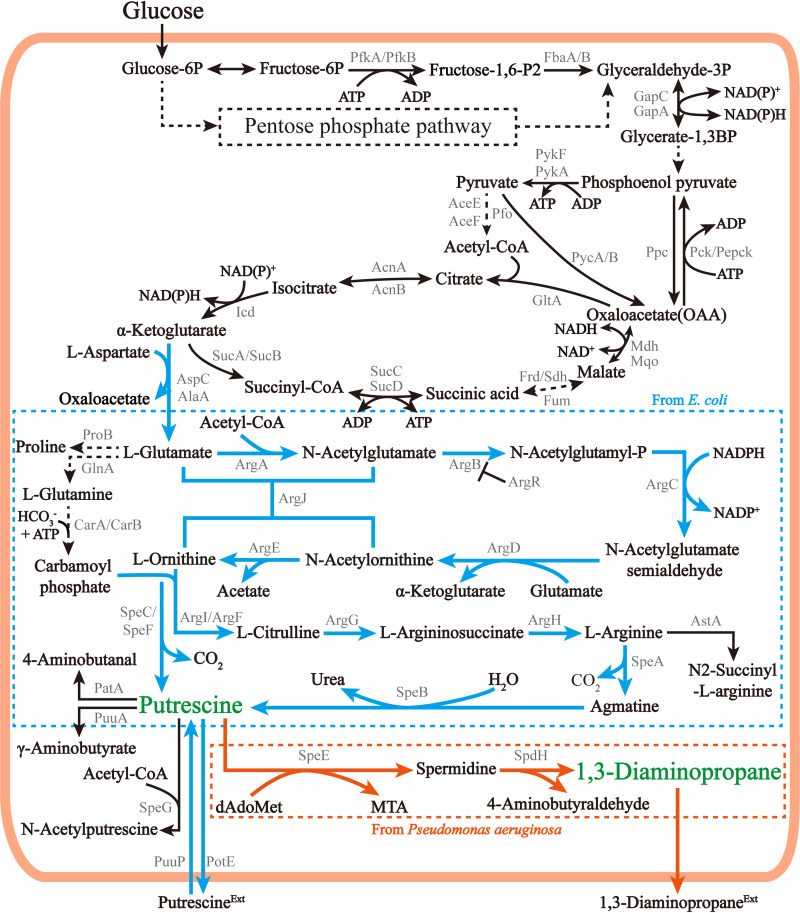

Currently, the biosynthetic pathways of common diamines (1,3-diaminopropane, putrescine, and 1,5-diaminopentane) have been identified in various microorganisms (14–17). According to the source of the carbon skeleton, diamine biosynthetic pathways can be divided into the C4 pathway (Fig. 1) and C5 pathway (Fig. 2); the C4 pathway is used for the synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane in Acinetobacter sp. and 1,5-diaminopentane in Escherichia coli and the C5 pathway is used for the synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane in Pseudomonas sp. and putrescine in E. coli. The carbon skeleton of diamines in the C4 pathway comes from oxaloacetate, while the carbon skeleton of diamines in the C5 pathways comes from α-ketoglutarate. Both oxaloacetate and α-ketoglutarate are derived from anaplerotic routes via phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (Ppc) or pyruvate carboxylase (Pyc), which are routes that serve to replenish tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolites that are withdrawn for biosynthesis. In the C4 pathway, 1,3-diaminopropane is formed by removing one carbon (CO2) from the 4-carbon skeleton oxaloacetate. 1,5-Diaminopentane is formed by adding a 3-carbon skeleton (pyruvate) on the 4-carbon skeleton oxaloacetate first and then removing 2 carbons. In the C5 pathway, with α-ketoglutarate as the 5-carbon skeleton, 1 carbon is removed to form the 4-carbon putrescine, and then the putrescine is further used in the synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane. This information show the key roles of oxaloacetate and α-ketoglutarate in the synthesis of diamines.

FIG 1.

Microbial metabolic C4 pathways for diamine production. Orange arrows represent metabolic pathways of 1,3-diaminopropane; yellow arrows represent metabolic pathways of 1,5-diaminopentane; black arrows represent conventional metabolic pathways; dashed lines represent multistep reactions. PfkA/PfkB, 6-phosphofructokinase; FbaA/B, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase; GapA/C, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PykF, pyruvate kinase I; PykA, pyruvate kinase II; Pfo, pyruvate-flavodoxin oxidoreductase; AceE/AceF, pyruvate dehydrogenase; Pyc, pyruvate carboxylase; GltA, citrate synthase; AcnAB, aconitate hydratase; Icd, isocitrate dehydrogenase; SucAB, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; SucCD, succinyl-CoA synthetase; Frd, fumarate reductase; Sdh, succinate dehydrogenase; Fum, fumarate hydratase; Mdh, l-malate-NAD+ oxidoreductase; Mqo, l-malate-quinone oxidoreductase; Pck, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; Ppc, the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; AspC, aspartate aminotransferase; LysC, aspartate kinase; Asd, aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase; Dat, diaminobutyrate-2-oxoglutarate transaminase; Ddc, l-2,4-diaminobutyrate decarboxylase; DapA, dihydrodipicolinic acid synthase; DapB, 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate reductase; Ddh, meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase; LysA, diaminopimelic acid decarboxylase; LdcC, l-lysine decarboxylase II; CadA, l-lysine decarboxylase I; YgjG, putrescine/α-ketoglutarate aminotransferase; PuuA, γ-glutamylputrescine synthase; PuuP, putrescine importer; SpeE, spermidine synthase; SpeG, spermidine N-acetyltransferase; NCgl1469, 1,5-diaminopentane acetyltransferase; CadB, 1,5-diaminopentane/l-lysine antiporter; CgmA, putrescine/1,5-diaminopentane exporter.

FIG 2.

Microbial metabolic C5 pathways for diamine production. Orange arrows represent metabolic pathways of 1,3-diaminopropane; blue arrows represent metabolic pathways of putrescine; black arrows represent conventional metabolic pathways; dashed lines represent multistep reactions. AspC, aspartate aminotransferase; AlaA, glutamate-pyruvate aminotransferase; ProB, glutamate 5-kinase; ArgA, amino acid N-acetyltransferase; ArgB, acetylglutamate kinase; ArgR, transcriptional regulator of arginine metabolism; ArgC, N-acetyl-gamma-glutamylphosphate reductase; ArgD, N-acetyl-l-ornithine aminotransferase; ArgE, acetylornithine deacetylase; ArgJ, l-glutamate N-acetyltransferase; GlnA, glutamine synthetase; CarAB, carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase; ArgI, ornithine carbamoyltransferase 1; ArgF, N-acetylornithine carbamoyltransferase; SpeC, ornithine decarboxylase; SpeF, ornithine decarboxylase isozyme; ArgG, citrulline-aspartate ligase; ArgH, arginosuccinase; SpeA, l-arginine decarboxylase; SpeB, agmatine ureohydrolase; AstA, arginine succinyltransferase; PotE, putrescine/l-ornithine antiporter; PatA, putrescine aminotransferase; SpdH, spermidine dehydrogenase; MTA, methylthioadenosine.

BIOPRODUCTION OF 1,3-DIAMINOPROPANE BASED ON NATURAL PATHWAYS

1,3-Diaminopropane is a diamine with a three-carbon backbone that can be employed as the raw material for the synthesis of medicines, agricultural chemicals, lubricants, and polyamides (12). Only a few microorganisms, such as Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species, are reported to possess natural 1,3-diaminopropane biosynthetic pathways, including C4 (Fig. 1) and C5 (Fig. 2) pathways (14). By utilizing the C4 pathway in Acinetobacter baumannii, 1,3-diaminopropane was synthesized by converting l-aspartate semialdehyde via the participation of l-2,4-diaminobutyrate 4-aminotransferase (Dat, encoded by the dat gene) (18) and l-2,4-diaminobutyrate decarboxylase (Ddc, encoded by the ddc gene) (19). A typical C5 pathway was found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in which 1,3-diaminopropane is directly synthesized by dehydrogenation of spermidine through the action of spermidine dehydrogenase (encoded by the spdH gene) (20).

Since the synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane was only reported in Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas species, the relative lack of genetic background information and gene manipulation tools for these two microbial systems limited the in vivo synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane. In 2015, Chae et al. (15) heterologously constructed a 1,3-diaminopropane synthesis pathway in E. coli. Before constructing the heterogeneous synthesis pathway of 1,3-diaminopropane, in silico flux response analysis was first performed to compare and analyze the production rates of the C4 and C5 pathways. The results showed that the production rate of 1,3-diaminopropane in the C4 pathway was relatively higher. The analysis found that, in the C4 pathway, the catalytic process of Dat and Ddc, the key enzymes for the synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane, did not require the participation of any cofactors, while in the C5 pathway, the catalysis of the limiting enzyme spermidine synthase (SpeE) requires S-adenosyl-3-methylthiopropylamine as a cofactor, which was the main reason for the low efficiency of the C5 pathway. Therefore, the C4 pathway was employed to synthesize 1,3-diaminopropane by overexpressing codon-optimized dat and ddc genes in E. coli TH02 that relieved feedback inhibition of some intracellular amino acids (i.e., l-threonine, l-isoleucine, and l-lysine), based on E. coli WL3110 by mutating two major aspartokinases (encoded by the thrA and lysC genes). Then, based on the synthetic small RNA (sRNA) screening and genetic necessity analysis, pfkA was selected as a gene knockout target. The results showed that the NADPH pool was increased owing to the enhanced flux through the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which provided sufficient NADPH for the synthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane (i.e., aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase Asd catalysis reaction). For elevating the oxaloacetate (an important precursor) pool, ppc (encoding the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase) or aspC (encoding the aspartate aminotransferase) was further overexpressed. Ultimately, the titer of 1,3-diaminopropane reached 13 g/liter in fed-batch fermentation using the pH-stat feeding strategy (15).

VARIOUS STRATEGIES FOR THE BIOSYNTHESIS OF PUTRESCINE

Putrescine, a biogenic diamine with a saturated four-carbon backbone, is used as a component in medicines, emulsifiers, insecticides, and other chemicals (12). In particular, putrescine combined with adipic acid can be used to synthesize the polyamide plastic nylon 46 by polymerization (21). Putrescine is naturally synthesized in many plants, animals, and microorganisms and has diverse physiological functions, such as regulation of transcription, translation (22, 23), and cell proliferation (24) and response to osmolarity, heat, reactive oxygen species, UV, and psychiatric stress (3). The biosynthetic pathway of putrescine includes the ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) pathway and the arginine decarboxylase (ADC) pathway (Fig. 2). Both the ADC and ODC pathways belong to the C5 pathway and are also components of the C5 pathway of 1,3-propanediamine synthesis. The ODC pathway is widely distributed in many animals, plants, and microorganisms, whereas the ADC pathway is found only in plants and bacteria (16). In the ODC pathway, putrescine is synthesized by decarboxylation of l-ornithine via ornithine decarboxylase SpeC or SpeF. In the ADC pathway in many bacteria, putrescine is generally synthesized by a two-step decarboxylation reaction of l-arginine via the action of arginine decarboxylases SpeA and SpeB (Fig. 2) (25). However, in plants and some bacteria, the second part of the decarboxylation reaction, agmatine decarboxylation, is completed by a two-step catalysis of agmatine amidinohydrolase AguA and N-carbamoyl putrescine amidase AguB (this pathway is not shown in Fig. 2) (26).

Biotransformation of putrescine in E. coli WL3110 has been reported (27). The titer of putrescine reached 24.2 g/liter by combining the ODC pathway with metabolic engineering, specifically deletion of argI, speE, speG, and puuPA genes to prevent putrescine utilization and degradation; overexpression of speC under the strong tac promoter with the low copy number plasmid p15SpeC; upregulation of argE, argCBH, argD, speF-potE, and speC genes by substituting the original promoters with the trc promoter to increase the metabolic flux and secretion of putrescine; and blocking the transcription factor encoded by rpoS to relieve the stress on the cell caused by putrescine overexpression. Using this strain, further downregulation expression of argF and glnA with fine-tuned synthetic small RNA (sRNA) achieved a putrescine titer of 42.3 g/liter (28).

In addition, the concentration of putrescine was at a level of 58.1 mM (∼5.12 g/liter) in the ornithine-overexpressing strain Corynebacterium glutamicum ORN1 in which a series of engineering strategies were combined. First, the speC gene was introduced by heterologous expression and then argF, proB, speE, and argR genes were knocked out (26). Second, a leaky and weak expression system was introduced for argF by inserting the argF gene with the weak promoter B6 (with an inactive −10 region) into the speC expression plasmid, which made up for the nutritional deficiency of arginine (29). Furthermore, the putrescine/polyamine N-acetyltransferase SnaA (encoded by cg1722) was deleted (30). A high titer of putrescine was ultimately obtained by further replacing the translational start codon GTG of the odhA gene (encoding alpha-ketoglutarate decarboxylase) with TTG, generating a variant of spermidine N-acetyltransferase (encoded by odhI gene) with replacements of 14 or 15 threonine residues by alanine, and overexpressing gapA and pyc genes (31).

In order to better convert ornithine to putrescine, Li et al. (32) compared the catalytic properties of 7 ornithine decarboxylases from different species. Finally, the speC1 gene from Enterobacter cloacae was found to be the most suitable ornithine decarboxylase gene for putrescine synthesis in C. glutamicum (32). Furthermore, Hwang et al. (33) found that the absence of putative NADP+-dependent glucose dehydrogenases (encoded by fabG, butA, and NCgl2053) can increase the accumulation of ornithine through increasing metabolic flux into the oxidative pentose phosphate (PP) pathway and can enhance the intracellular NADPH availability. Therefore, Li et al. (32) replaced the fabG and puo genes with speC1 in ORN1, and the results showed that the replacement of fabG was superior to that of puo. Based on the replacement of fabG, butA and NCgl2053 were deleted in turn, and it was found that only the deletion of butA was effective, which increased the production of putrescine to about 31.1 mM. Furthermore, the snaA gene was deleted to block putrescine acetylation, which increased the putrescine titer to 56.7 mM (∼5.00 g/liter). Based on a comparative proteome analysis of strains treated by adaptive laboratory evolution, expression of the odhA gene was weakened to channel more carbon flux into putrescine biosynthesis by exchanging the native start codon GTG for TTG. Afterward, the cgmA gene (encoded putative export putrescine permease) was overexpressed, and the putrescine production reached to 125.0 mM (∼11.0 g/liter). Similarly, putrescine production reached 126.7 mM (∼11.2 g/liter) by overexpressing the mutant of the pyc gene (P458S), encoding important anaplerotic enzymes in C. glutamicum, which had the potential to improve the production of l-glutamate (34, 35), l-arginine (36), l-lysine (37), and putrescine (31). Furthermore, based on proteomics analysis, the CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) system was employed to inhibit amino acid biosynthesis, and the results proved that the downregulation of carB, ilvH, ilvB, and aroE effectively increased putrescine production (32).

Due to environmental protection and economic costs, methane, a typical one-carbon (C1) substance, was used to biosynthesize putrescine based on metabolic engineering of Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z (38). First, the tolerance of the strain to putrescine was improved by adaptive evolution. Next, ornithine decarboxylase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b was overexpressed, and the titer of putrescine from methane reached 0.1 g/liter following deletion of genes encoding spermidine synthase, acetate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase, overexpressing genes argD and argJ, and optimizing the concentration of the inorganic nitrogen source (38).

Furthermore, Choi et al. (39) rationally designed the variant SpeF-I163T/E165T with a 62.5-fold increase in catalytic efficiency, which broadened the substrate tunnels and increased the stability of the dimer interface of the ornithine decarboxylase. The substrate selectivity of ornithine decarboxylase was optimized further to increase the productivity of putrescine by introducing mutation A713L in the ornithine decarboxylase from Lactobacillus sp. (40). Afterward, the developed putrescine responsive biosensor was designed successfully, which accelerated the screening of engineered strains with strong putrescine synthesis efficiency (41). These studies will further promote the industrial development of putrescine.

METABOLIC ENGINEERING FOR IMPROVING THE PRODUCTIVITY OF 1,5-DIAMINOPENTANE

1,5-Diaminopentane can be used as a precursor for polyamides, polyurethanes, and chelating agents (42). In many microorganisms, l-lysine can be converted to 1,5-diaminopentane naturally by decarboxylation (Fig. 1). This natural biosynthetic pathway is present in typical engineering strains of E. coli, which can synthesize 1,5-diaminopentane with a titer up to 9.6 g/liter (17). In order to increase the yield, key synthetic enzymes l-lysine decarboxylase (CadA) and DapA were overexpressed based on the plasmid and genomic promoter replacement, respectively, and enzymes related to utilization and degradation (encoded by speE, speG, ygjG, and puuA) were deleted (17). Furthermore, the murE gene (encoding a ligase involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis) was selected as a target for downregulation using an sRNA library based on genome-wide knockdown target screening, and the titer reached 12.6 g/liter in fed-batch culture (43).

A large number of metabolic engineering studies have been performed in C. glutamicum for overproduction of 1,5-diaminopentane because this strain has a high capacity for l-lysine production. Initially, in order to increase the flux to 1,5-diaminopentane, the hom gene (encoding the key enzyme l-homoserine dehydrogenase) entering the competitive threonine pathway was replaced with the cadA gene from E. coli based on C. glutamicum ATCC 13032, which produced 1,5-diaminopentane with a titer of 2.6 g/liter (44). Similarly, the genes of E. coli CadA and Streptococcus bovis 148 α-amylase (AmyA) were coexpressed in the strain deleted the hom gene based on C. glutamicum ATCC 13032. 1,5-Diaminopentane was successfully produced from soluble starch with a titer of 49.4 mM (∼5.1 g/liter) (45). Moreover, the 1,5-diaminopentane production strain was engineered based on C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 lysC311 for maintaining a sufficient lysine precursor. First, the ldcC gene (encoding lysine decarboxylase) from E. coli was overexpressed to catalyze the conversion of lysine into 1,5-diaminopentane. Then, the genes encoding aspartokinase (lysC311), dihydrodipicolinate reductase (dapB), diaminopimelate dehydrogenase (ddh), and diaminopimelate decarboxylase (lysA) were overexpressed, which were related to almost all enzymes of the biosynthetic route, and the flux of the competing threonine pathway was weakened by using the leaky mutation hom59. Simultaneously, pycA (encoding the major anaplerotic enzyme catalyzing the synthesis of oxaloacetate) was modified by introduction of a beneficial point mutation, P458S, and the expression of this mutant was amplified by replacing native promoter with the strong sod promoter. The phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene (pepck) was also deleted to block the return of oxaloacetate to glycolysis. To avoid the use of antibiotics, genome-based expression of ldcC was implemented by integrating the ldcC gene into the bioD locus and replacing the native promoter with the promoter of the tuf gene. Furthermore, the level of translation of ldcC was improved through codon optimization, which made the yield of 1,5-diaminopentane reach 200 mmol/mol glucose. The yield of 1,5-diaminopentane was improved to 300 mmol/mol glucose by supplementing the pyridoxal cofactor (46). Moreover, Kind et al. (47) further inhibited the accumulation of the by-product N-acetyl diaminopentane based on the aforementioned research by deleting the NCgl1469 gene encoding diaminopentane acetyltransferase. Eventually the yield of 1,5-diaminopentane reached 223 mmol/mol glucose without supplementing the cofactor. Next, deletion of the l-lysine exporter gene lysE was employed to block the secretion of the key intermediate l-lysine, and overexpression of permease gene cg2893 combined with deletion of cg2894, a TetR-type repressor of cg2893, were carried out to accelerate the extracellular transport of 1,5-diaminopentane. Using these strategies, the 1,5-diaminopentane yield reached 219 mmol/mol glucose (48), and the titer reached 88 g/liter in fed-batch fermentation (49).

Meanwhile, the conversion of 1,5-diaminopentane from nonfood raw materials has been researched due to environmental issues and resource scarcity (50, 51). In recent studies, 1,5-diaminopentane was synthesized from xylose with a titer of 103 g/liter in fed-batch mode by heterologously expressing the xylA and xylB genes, combined with enlargement of the tkt operon, overexpression of the fbp gene, downregulation of the sucCD and isocitrate dehydrogenase gene, and deletion of the cg1722 and lysE genes (50, 51). Additionally, a titer of 1,5-diaminopentane (11.3 g/liter) was achieved by converting methanol using Bacillus methanolicus expressing E. coli genes cadA and ldcC (52).

Recently, there have also been some breakthroughs in the industrial fermentation production of 1,5-diaminopentane. Based on an industrial l-lysine-producing strain, the titer of 1,5-diaminopentane reached 103.8 g/liter in a 2.5-liter fed-batch culture by integrating ldcC from E. coli into the lysE locus of C. glutamicum PKC (53). In addition, Rui et al. (54) performed strategies, such as promoter optimization, permeabilized cell treatment, and the substrate and cell concentration optimization, to improve the titer of 1,5-diaminopentane. First, the cost of the inducer was effectively reduced by employing the cad promoter induced by l-lysine to overexpress the cadA gene because this inducer is less expensive than isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and is used as a substrate for conversion to 1,5-diaminopentane. Then, the cell permeability was enhanced by destroying the structure of the cell membrane phospholipid using ethanol, which facilitated the entry of the substrate and the release of the product. Furthermore, 1,5-diaminopentane reached the highest titer to date (220 g/liter) with the yield 98.5% when the concentration of l-lysine-HCl was 400 g/liter and the cell concentration was 3.5 g/liter. Finally, after enlarging the fermentation scale from a 500-ml flask to 7 liters, the titer of 1,5-diaminopentane reached 205 g/liter under the optimal conditions, namely, 35% ethanol concentration, 2-g/liter cell concentration, and 20-min permeabilization time. At the same time, the production cost of 1,5-diaminopentane was reduced significantly ($30.88 to $2.78) through replacing the laboratory reagents using industrial materials, which was conducive to the industrial production of 1,5-diaminopentane (54).

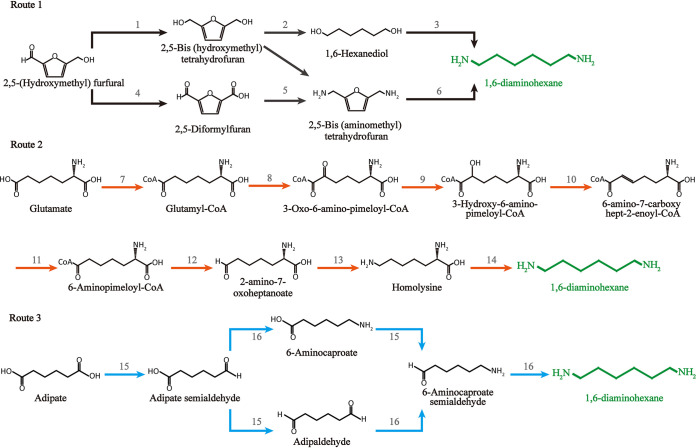

BIOSYNTHESIS OF 1,6-DIAMINOHEXANE

1,6-Diaminohexane is an important chemical for the synthesis of polyamides (e.g., nylon 66 and nylon 610), bleach, stabilizers, polyurethane curing agents, and organic cross-linking agents (12, 55). Natural 1,6-diaminohexane biosynthetic pathways have not been reported, and existing metabolic pathways have been constructed de novo based on enzymes catalyzing multiple complicated steps in microorganisms, which demonstrates the challenge of 1,6-diaminohexane biosynthesis (56–59). At present, multiple 1,6-diaminohexane synthetic pathways starting from 2,5-(hydroxymethyl) furfural, glutamate and adipate have been proposed (Fig. 3). First, Dros et al. investigated the economic feasibility, environmental impact, and potential risks and benefits of 1,6-diaminohexane biological transformation via route 1 (Fig. 3) and revealed that the bio-based routes were more favorable from an environmental perspective due to their having lower CO2 emissions (59). Subsequently, the key enzymes in route 2 (glutamyl-coenzyme A [CoA] transferase, beta-ketothiolase, 2-oxo-acid reductase, dehydratase, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, dehydrogenase, amine dehydrogenase, and homolysine decarboxylase) were overexpressed heterologously in E. coli, and engineering bacteria achieved a titer of 0.5 g/liter 1,6-diaminohexane from 2 g/liter glucose (57).

FIG 3.

Metabolic pathways for 1,6-diaminohexane. The black arrow represents route 1. The orange arrow represents route 2. The blue arrow represents route 3. Key enzymes were as follows: hydrogenase, 1; hydrolase, 2; aminase, 3; oxidase, 4; reductive aminase, 5; hydrodeoxygenase, 6; glutamyl-CoA transferase and/or ligase, 7; beta-ketothiolase, 8; 2-oxo-acid reductase, 9; dehydratase, 10; acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, 11; dehydrogenase, 12; amine dehydrogenase, 13; homolysine decarboxylase, 14; carboxylic acid reductases, 15; transaminase, 16.

In one study (58), adipic acid was converted to 1,6-diaminohexane successfully in a one-pot biocatalytic transformation using carboxylic acid reductases (CARs; e.g., MAB4714 from Mycobacterium chelonae) and transaminases (TAs; e.g., SAV2585 from Streptomyces avermitilis and putrescine TA PatA from E. coli) (route 3, Fig. 2). This cascade reaction required some cofactors, including ATP, NADPH, and an amine donor (l-Glu or l-Ala), and a cofactor regenerating system was employed. Simultaneously, the conversion of 6-aminohexanoic acid to 1,6-diaminohexane was improved by engineering the CAR L342E variant. The conversion of 1,6-diaminohexane and 6-aminocaproate was improved to 30% and 70%, respectively, by utilizing the wild-type CAR, the L342E variant, and the two different TAs.

BIO-BASED DIAMINES FOR APPLICATION TO BIO-BASED NYLON MATERIALS

Diamine is one of the important raw materials to use for producing nylon plastics. The change of its production mode has an important impact on the production of nylon in the industry. At present, the main purpose of most bio-based diamine research is the production of bio-based nylon. Thus, the broad market demand for bio-based nylon has increased the application prospects of bio-based diamines. Nylon is widely used in automobiles, electrical and electronics applications, textiles, and other materials, due to its high-tensile strength, high elasticity, and excellent abrasion resistance. The global nylon market value in 2019 reached ∼$28.57 billion, and it is estimated to achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.9% between 2020 and 2027 (https://www.24chemicalresearch.com/reports/25044/global-nylon-2019-991). With the development of environmentally friendly substitutes, the bio-based nylon will improve the competitiveness of nylon. However, the production of nylon mainly depends on chemical synthesis, and bio-based synthesis is still in the development stage, although bio-based nylon 11 is already commercially available (60, 61). In 2013, with the synthesis of bio-based 2-pyrrolidone from γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) produced by engineered E. coli, bio-based nylon 4 was synthesized from 2-pyrrolidone (62). Furthermore, nylon 6 and nylon 5 were also synthesized based on ε-caprolactam and δ-valerolactam from bio-transformed 5-aminovalerate in E. coli WL3110, respectively (63).

Obviously, biosynthesis of various nylon monomers is a key limiting factor in the development of bio-based nylon materials. In order to realize the synthesis of whole bio-based nylon, in advancing the development of bio-based diamines, the bio-based production of important nylon monomer dicarboxylic acid has also achieved remarkable results, such as the bio-based synthesis of adipic acid (64). Based on bio-based diamines and dicarboxylic acids, bio-based nylon 56 (65) and nylon 510 (49) have been prepared. Following this trend, with the further improvement of bio-based diamines (including putrescine and 1,6-diaminohexane), the synthesis of all-bio-based nylon, such as nylon 46 and nylon 66, will eventually be realized in the near future.

PROSPECTS

In recent years, the biosynthesis of diamines has gradually attracted the attention of researchers in the field of platform chemicals. Diamine biosynthesis systems were successfully established in E. coli, C. glutamicum, and other microbes, and this will accelerate the development of many other diamine biosynthesis systems in the future. Currently, the most well-established diamine biosynthetic systems are for putrescine and 1,5-diaminopentane, with the highest titers being 42.3 g/liter and 103.8 g/liter, respectively (28, 53). The biosynthesis of 1,3-diaminopropane, 1,6-diaminohexane, and other long-chain diamines still needs to be improved by combining metabolic and enzyme engineering approaches. Although biosynthetic pathways for 1,6-diaminohexane have been designed de novo based on the principle of biological enzyme catalysis, simplifying the complex enzyme-catalyzed pathway and incorporating it into host microorganisms are bottlenecks to the whole-cell biosynthesis of 1,6-diaminohexane (56, 57, 59).

Although the biosynthetic pathway for 1,3-diaminopropane has been identified in some Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species (14), the application of its biosynthetic pathways is still scarce, and it is only applied in E. coli (15). Actually, in recent years, Pseudomonas sp. has attracted the attention of researchers due to its excellent resistance to harsh environments, chemical stresses, and physical stresses (66). With the continuous improvement of gene manipulation tools, including genome editing tools (67, 68), DNA assembly technologies (11, 69), and corresponding standardized vectors (70), Pseudomonas sp. has gradually become a new type of flexible and operable metabolic engineering platform strains, such as Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (71). Therefore, the construction of the 1,3-diaminopropane engineering strain based on Pseudomonas sp. and using its endogenous pathway show great development prospects. Simultaneously, it cannot be ignored that Pseudomonas sp. also contains degradation pathways of biogenic amines (72). So, the corresponding degradation pathways need to be suppressed when Pseudomonas sp. is used in the production of bio-based diamines. The selection of suitable expression hosts, simplification of branched metabolic pathways, identification of main by-products and catabolism pathways, and improvement of enzymatic properties (e.g., enzyme activity, enzyme substrate specificity, and stability) of key enzymes (e.g., Ddc and AspC) could be the key to overcome the challenges of producing bio-based 1,3-diaminopropane.

Based on the reported synthesis pathways of diamines, the stoichiometric equations of 1,3-diaminopropane, putrescine, and 1,5-diaminopentane have been obtained (Table 2) (14–17). The C4 pathway of 1,3-diaminopropane only requires the participation of 1 mol glucose, 4 mol NH3, 4 mol NADH, and 2 mol ATP. In comparison, the C5 pathway of 1,3-diaminopropane requires more glucose and the additional special cofactor dAdoMet but can synthesize NADPH, NADH, and ATP. To a certain extent, this finding also confirms the conclusion in the study of Chae et al. that the production rate of 1,3-diaminopropane from the C4 pathway was higher than that from the C5 pathway (15). In contrast to the ADC pathway, the ODC pathway of putrescine does not need to consume ATP but produces 2 mol ATP. This was one of reasons that the ODC pathway was mostly used in the synthesis of putrescine. The most typical representative was that Noh et al. achieved the highest putrescine titer (42.3 g/liter) using the ODC pathway (28). In addition, it can be seen from Fig. 2 that the C5 pathway of 1,3-diaminopropane is constituted by adding two catalytic reactions based on the biosynthetic of putrescine, which reveals the feasibility of using putrescine high-yielding strains to produce 1,3-diaminopropane. In the C4 pathway, the synthesis of 1 mol 1,5-diaminopentane needs to consume 1 mol glucose, 2 mol NADH, and 2 mol NH3. In contrast to the C4 pathway of 1,3-propanediamine, this process does not need to consume ATP, but the theoretical yield of 1,5-diaminopentane for glucose is lower than that of 1,3-propanediamine. As shown in Fig. 1 and 2, the synthesis of diamines often requires the participation of l-glutamate, l-aspartate, or pyruvate. Ensuring an adequate supply of these precursors will benefit the synthesis of diamines. For instance, Chae et al. overexpressed the aspC gene during the production of 1,3-diaminopropane to increase the accumulation of l-aspartate precursors (15). In order to increase the synthesis of putrescine, Noh et al. used sRNA to suppress the expression of glnA and reduce the consumption of glutamate (28). Moreover, the balance of cofactors in the diamine metabolic system is also an important factor (73). The production of 1,3-diaminopropane was increased by knocking out pfkA to increase the NADPH pool (15). Li et al. (32) adjusted the balance of reducing power in the putrescine synthesis system by deleting NADP+-dependent glucose dehydrogenase genes fabG and butA. Furthermore, King et al. increased NADPH production and increased theoretical yields for putrescine in E. coli by swapping the cofactor specificity of central metabolic enzymes (especially glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPD] and alcohol dehydrogenase [ALCD2x]) (74), which can also be applied to other diamines for increasing their theoretical yields.

TABLE 2.

The stoichiometric equations of common diamine biosynthetic pathways

| Diamine | Pathway | Chemometric equation |

|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Diaminopropane | C4 | glucose + 4 NH3 + 4 NADH + 4 H+ + 2 ATP → 2 1,3-diaminopropane + 2 phosphate + 4 NAD+ + 2 ADP + 4 H2O |

| C5 (ODC) | 3 glucose + 4 NH3 + 2 phosphate + 6 NADP+ + 2 NAD+ + 2 ADP + 2 dAdoMet → 2 1,3-diaminopropane + 2 acetate + 2 ATP + 6 NADPH + 2 NADH + 8 H+ + 6 CO2 + 2 H2O + 2 MTA + 2 4-aminobutyraldehyde | |

| Putrescine | C5 (ODC) | 3 glucose + 2 phosphate + 2 ADP + 6 NADP+ + 4 NH3 → 2 putrescine + 2 acetate + 2 ATP + 6 NADPH + 6 H+ + 6 CO2 + 4 H2O |

| C5 (ADC) | 3 glucose + 4 ATP + 6 NADP+ + 8 NH3 → 2 putrescine + 2 acetate + 2 phosphate + 2 diphosphate + 2 urea + 2 ADP + 2 AMP + 6 NADPH + 6 H+ + 4 CO2 | |

| 1,5-Diaminopentane | C4 | glucose + 2 NH3 + 2 NADH + 2 H+ → 1,5-diaminopentane + 2 NAD+ + CO2 + 4 H2O |

With the development of other bio-based monomers, such as dicarboxylic acids (64), researchers are paying more attention to the application of bio-based diamines in the synthesis of nylon materials. Polymerization reactions between bio-based diamines and bio-based dicarboxylic acids will become important for preparing bio-based nylon materials. The performance of nylon material is closely related to the purity of diamine or dicarboxylic acid monomers. However, the fermentation system of bio-based diamine monomers is relatively complicated, which increases the complexity of purification (53, 75). How to obtain a high-purity diamine monomer through a simple, efficient, and easy-to-industrialize purification process will be a challenge that must be overcome in the industrialization of bio-based nylon.

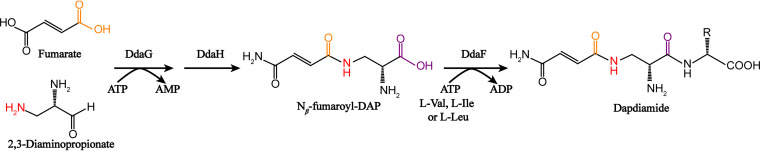

Some microorganisms are able to synthesize polymers directly. For example, Xu et al. (76) successfully achieved biodegradable polymer γ-polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) production through heterologously expressing γ-PGA synthase complex Cap A, B, and C from Bacillus licheniformis in Corynebacterium glutamicum; Dong et al. (77) synthesized α-methyl-branched polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) in E. coli by introducing PHA polymerase (CapPhaEC) identified from wastewater activated sludge and using glucose and propionate as carbon sources. Therefore, investigating the potential for synthesizing oligomeric amide in living organisms will be very interesting. The synthesis of polyamide is the process of formation of an amide bond. Recently, Goswami and Van Lanen (78) comprehensively introduced the formation of amide bonds in nonprotein amide bond-containing biomolecules, including the one between carboxylic acids and amines. The amide bond synthetase between organic acids and organic amines was mainly ATP-grasp enzymes, such as d-Ala ligase, glutathione synthetase, glycinamide ribonucleotide synthetase (PurD), carnosine synthetase, tyramine-glutamate ligase (MfnD), ribosomal protein S6 modification protein (RimK), and tubulin-tyrosine ligase (79). Hollenhorst et al. (80, 81) found that the adenylate-forming ligase DdaG and amidotransferase DdaH could jointly catalyze the formation of and amide bond between fumarate and 2,3-diaminopropionate, and then the ATP-grasp enzyme DdaF further catalyzed the intermediate Nβ-fumaroyl-DAP to synthesize dapdiamide by forming the second amide bond with l-amino acid (Fig. 4). The formation of amide bonds is a typical thermodynamically challenging event. The carboxylic acid substrates needed to be activated as acyl phosphate intermediates before being condensed with nucleophilic substrates (amines or thiols), and then a tetrahedral intermediate was formed by a nucleophilic attack, which in turn formed an amide bond (82–84). Although the research on the catalytic mechanism of amide bond synthetase is limited, based on the existing enzyme system, it has great potential to give the amide synthetase new substrate activity (diamines and dicarboxylic acids) by engineering enzyme structure utilizing various enzyme modification and design tools, which will be significant for the whole-cell production of oligomeric polyamide.

FIG 4.

The biological enzymatic synthesis of dapdiamide with two amide bonds. DdaG, adenylate-forming ligases; DdaH, amidotransferase; DdaF, ATP-grasp enzyme.

Finally, bio-based diamines still lack economic competitiveness against diamines prepared by chemical synthesis. To improve the competitiveness of bio-based diamines, the first task is to increase the yield of bio-based diamines, followed by improving the properties of key enzymes, optimizing metabolic pathways, and simplifying the production and purification process could be applied. Meanwhile, conversion of bio-based diamines from inexpensive nonedible renewable raw materials (such as hemicellulose and lignocellulose) or C1 raw materials will become the focus. Environmentally friendly and sustainable biosynthesis of diamines is expected to become a viable alternative for producing diamines, which will also promote the development of bio-based nylon materials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0901400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21877053 and 22008088), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP51705A, JUSRP11964).

We declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wendisch VF, Mindt M, Pérez-García F. 2018. Biotechnological production of mono-and diamines using bacteria: recent progress, applications, and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:3583–3594. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8890-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurata HT, Marton LJ, Nichols CG. 2006. The polyamine binding site in inward rectifier K+ channels. J Gen Physiol 127:467–480. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhee H, Kim E-J, Lee J. 2007. Physiological polyamines: simple primordial stress molecules. J Cell Mol Med 11:685–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takatsuka Y, Kamio Y. 2004. Molecular dissection of the Selenomonas ruminantium cell envelope and lysine decarboxylase involved in the biosynthesis of a polyamine covalently linked to the cell wall peptidoglycan layer. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:1–19. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturgill G, Rather PN. 2004. Evidence that putrescine acts as an extracellular signal required for swarming in Proteus mirabilis. Mol Microbiol 51:437–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen B, Makley DM, Johnston JN. 2010. Umpolung reactivity in amide and peptide synthesis. Nature 465:1027–1032. doi: 10.1038/nature09125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng H, Guan Z. 2011. Direct synthesis of polyamides via catalytic dehydrogenation of diols and diamines. J Am Chem Soc 133:1159–1161. doi: 10.1021/ja106958s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babu RP, O'connor K, Seeram R. 2013. Current progress on bio-based polymers and their future trends. Prog Biomater 2:8. doi: 10.1186/2194-0517-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawaguchi H, Ogino C, Kondo A. 2017. Microbial conversion of biomass into bio-based polymers. Bioresour Technol 245:1664–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Commission. 2018. A European strategy for plastics in a circular economy. European Commission, Brussels, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi KR, Jang WD, Yang D, Cho JS, Park D, Lee SY. 2019. Systems metabolic engineering strategies: integrating systems and synthetic biology with metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol 37:817–837. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chae TU, Ahn JH, Ko Y-S, Kim JW, Lee JA, Lee EH, Lee SY. 2020. Metabolic engineering for the production of dicarboxylic acids and diamines. Metab Eng 58:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang YS, Kim B, Shin JH, Choi YJ, Choi S, Song CW, Lee J, Park HG, Lee SY. 2012. Bio-based production of C2-C6 platform chemicals. Biotechnol Bioeng 109:2437–2459. doi: 10.1002/bit.24599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabor CW, Tabor H. 1985. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev 49:81–99. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chae TU, Kim WJ, Choi S, Park SJ, Lee SY. 2015. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of 1,3-diaminopropane, a three carbon diamine. Sci Rep 5:13040. doi: 10.1038/srep13040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabor CW, Tabor H. 1976. 1,4-Diaminobutane (putrescine), spermidine, and spermine. Annu Rev Biochem 45:285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.45.070176.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian Z-G, Xia X-X, Lee SY. 2011. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of cadaverine: a five carbon diamine. Biotechnol Bioeng 108:93–103. doi: 10.1002/bit.22918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikai H, Yamamoto S. 1997. Identification and analysis of a gene encoding l-2,4-diaminobutyrate:2-ketoglutarate 4-aminotransferase involved in the 1,3-diaminopropane production pathway in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 179:5118–5125. doi: 10.1128/JB.179.16.5118-5125.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikai H, Yamamoto S. 1994. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene encoding a novel l-2,4-diaminobutyrate decarboxylase of Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett 124:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(94)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dasu VV, Nakada Y, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Kimura K, Itoh Y. 2006. Characterization and a role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa spermidine dehydrogenase in polyamine catabolism. Microbiology (Reading) 152:2265–2272. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endah YK, Han SH, Kim JH, Kim NK, Kim WN, Lee HS, Lee H. 2016. Solid-state polymerization and characterization of a copolyamide based on adipic acid, 1,4-butanediamine, and 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid. J Appl Polym Sci 133:43391. doi: 10.1002/app.43391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephenson AH, Christian JF, Seidel ER. 2004. Polyamines regulate eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 gene transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Childs AC, Mehta DJ, Gerner EW. 2003. Polyamine-dependent gene expression. Cell Mol Life Sci 60:1394–1406. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2332-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anuradha Banerjee A, Krishna A. 2019. Role of putrescine in ovary and embryo development in fruit bat Cynopterus sphinx during embryonic diapause. Mol Reprod Dev 86:1963–1980. doi: 10.1002/mrd.23281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Piérard A, Stalon V. 1986. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol Rev 50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jens S, Wendisch VF. 2010. Putrescine production by engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 88:859–868. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2778-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian ZG, Xia XX, Lee SY. 2009. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of putrescine: a four carbon diamine. Biotechnol Bioeng 104:651–662. doi: 10.1002/bit.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noh M, Yoo SM, Kim WJ, Lee SY. 2017. Gene expression knockdown by modulating synthetic small RNA expression in Escherichia coli. Cell Syst 5:418–426.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider J, Eberhardt D, Wendisch VF. 2012. Improving putrescine production by Corynebacterium glutamicum by fine-tuning ornithine transcarbamoylase activity using a plasmid addiction system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 95:169–178. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen AQD, Schneider J, Wendisch VF. 2015. Elimination of polyamine N -acetylation and regulatory engineering improved putrescine production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 201:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen A, Schneider J, Reddy G, Wendisch V. 2015. Fermentative production of the diamine putrescine: system metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metabolites 5:211–231. doi: 10.3390/metabo5020211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Shen Y-P, Jiang X-L, Feng L-S, Liu J-Z. 2018. Metabolic evolution and a comparative omics analysis of Corynebacterium glutamicum for putrescine production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 45:123–117. doi: 10.1007/s10295-018-2003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang G-H, Cho J-Y. 2014. Enhancement of l-ornithine production by disruption of three genes encoding putative oxidoreductases in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 41:573–578. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasegawa T, Hashimoto K, Kawasaki H, Nakamatsu T. 2008. Changes in enzyme activities at the pyruvate node in glutamate-overproducing Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biosci Bioeng 105:12–19. doi: 10.1263/jbb.105.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shirai T, Fujimura K, Furusawa C, Nagahisa K, Shioya S, Shimizu H. 2007. Study on roles of anaplerotic pathways in glutamate overproduction of Corynebacterium glutamicum by metabolic flux analysis. Microb Cell Fact 6:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Man Z, Xu M, Rao Z, Guo J, Yang T, Zhang X, Xu Z. 2016. Systems pathway engineering of Corynebacterium crenatum for improved l-arginine production. Sci Rep 6:28629. doi: 10.1038/srep28629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters-Wendisch PG, Schiel B, Wendisch VF, Katsoulidis E, Möckel B, Sahm H, Eikmanns BJ. 2001. Pyruvate carboxylase is a major bottleneck for glutamate and lysine production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 3:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen LT, Lee EY. 2019. Biological conversion of methane to putrescine using genome-scale model-guided metabolic engineering of a methanotrophic bacterium Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z. Biotechnol Biofuels 12:147. doi: 10.1186/s13068-019-1490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi H, Kyeong H-H, Choi JM, Kim H-S. 2014. Rational design of ornithine decarboxylase with high catalytic activity for the production of putrescine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:7483–7490. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong EY, Kim JY, Upadhyay R, Park BJ, Lee JM, Kim B-G. 2018. Rational engineering of ornithine decarboxylase with greater selectivity for ornithine over lysine through protein network analysis. J Biotechnol 281:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X-F, Xia X-X, Lee SY, Qian Z-G. 2018. Engineering tunable biosensors for monitoring putrescine in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 115:1014–1027. doi: 10.1002/bit.26521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stefanie K, Christoph W. 2011. Bio-based production of the platform chemical 1,5-diaminopentane. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 91:1287–1296. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Na D, Yoo SM, Chung H, Park H, Park JH, Lee SY. 2013. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using synthetic small regulatory RNAs. Nat Biotechnol 31:170–174. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mimitsuka T, Sawai H, Hatsu M, Yamada K. 2007. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for cadaverine fermentation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 71:2130–2135. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tateno T, Okada Y, Tsuchidate T, Tanaka T, Fukuda H, Kondo A. 2009. Direct production of cadaverine from soluble starch using Corynebacterium glutamicum coexpressing α-amylase and lysine decarboxylase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kind S, Jeong WK, Schröder H, Wittmann C. 2010. Systems-wide metabolic pathway engineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum for bio-based production of diaminopentane. Metab Eng 12:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kind S, Jeong WK, Schröder H, Zelder O, Wittmann C. 2010. Identification and elimination of the competing N-acetyldiaminopentane pathway for improved production of diaminopentane by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5175–5180. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00834-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kind S, Kreye S, Wittmann C. 2011. Metabolic engineering of cellular transport for overproduction of the platform chemical 1,5-diaminopentane in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab Eng 13:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kind S, Neubauer S, Becker J, Yamamoto M, Völkert M, von Abendroth G, Zelder O, Wittmann C. 2014. From zero to hero-production of bio-based nylon from renewable resources using engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab Eng 25:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buschke N, Schröder H, Wittmann C. 2011. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of 1, 5-diaminopentane from hemicellulose. Biotechnol J 6:306–317. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buschke N, Becker J, Schäfer R, Kiefer P, Biedendieck R, Wittmann C. 2013. Systems metabolic engineering of xylose-utilizing Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of 1,5-diaminopentane. Biotechnol J 8:557–570. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naerdal I, Pfeifenschneider J, Brautaset T, Wendisch VF. 2015. Methanol-based cadaverine production by genetically engineered Bacillus methanolicus strains. Microb Biotechnol 8:342–350. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HT, Baritugo K-A, Oh YH, Hyun SM, Khang TU, Kang KH, Jung SH, Song BK, Park K, Kim I-K, Lee MO, Kam Y, Hwang YT, Park SJ, Joo JC. 2018. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the high-level production of cadaverine that can be used for the synthesis of biopolyamide 510. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 6:5296–5305. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rui J, You S, Zheng Y, Wang C, Gao Y, Zhang W, Qi W, Su R, He Z. 2020. High-efficiency and low-cost production of cadaverine from a permeabilized-cell bioconversion by a lysine-induced engineered Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol 302:122844. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vardon DR, Rorrer NA, Salvachúa D, Settle AE, Johnson CW, Menart MJ, Cleveland NS, Ciesielski PN, Steirer KX, Dorgan JR, Beckham GT. 2016. cis, cis-Muconic acid: separation and catalysis to bio-adipic acid for nylon-6, 6 polymerization. Green Chem 18:3397–3413. doi: 10.1039/C5GC02844B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burk MJ, Burgard AP, Osterhout RE, Pharkya P. February 2013. Microorganisms and methods for the biosynthesis of adipate, hexamethylenediamine and 6-aminocaproic acid. US patent 8,377,680.

- 57.Lau MK. 23 Recombinant bacterial cells producing (S)-2-amino-6-hydroxypimelate. US patent 9,890,405.

- 58.Fedorchuk TP, Khusnutdinova AN, Evdokimova E, Flick R, Di Leo R, Stogios P, Savchenko A, Yakunin AF. 2020. One-pot biocatalytic transformation of adipic acid to 6-aminocaproic acid and 1, 6-hexamethylenediamine using carboxylic acid reductases and transaminases. J Am Chem Soc 142:1038–1048. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dros A, Larue O, Reimond A, De Campo F, Pera-Titus M. 2015. Hexamethylenediamine (HMDA) from fossil-vs. bio-based routes: an economic and life cycle assessment comparative study. Green Chem 17:4760–4772. doi: 10.1039/C5GC01549A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Magniez K, Iftikhar R, Fox BL. 2015. Properties of bio-based polymer nylon 11 reinforced with short carbon fiber composites. Polym Compos 36:668–674. doi: 10.1002/pc.22985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naffakh M, Shuttleworth PS, Ellis G. 2015. Bio-based polymer nanocomposites based on nylon 11 and WS 2 inorganic nanotubes. RSC Adv 5:17879–17887. doi: 10.1039/C4RA17210H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park SJ, Kim EY, Noh W, Oh YH, Kim HY, Song BK, Cho KM, Hong SH, Lee SH, Jegal J. 2013. Synthesis of nylon 4 from gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) produced by recombinant Escherichia coli. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 36:885–892. doi: 10.1007/s00449-012-0821-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park SJ, Oh YH, Noh W, Kim HY, Shin JH, Lee EG, Lee S, David Y, Baylon MG, Song BK, Jegal J, Lee SY, Lee SH. 2014. High-level conversion of l-lysine into 5-aminovalerate that can be used for nylon 6, 5 synthesis. Biotechnol J 9:1322–1328. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao M, Huang D, Zhang X, Koffas MA, Zhou J, Deng Y. 2018. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for producing adipic acid through the reverse adipate-degradation pathway. Metab Eng 47:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li YL, Hao XM, Guo YF, Chen X, Yang Y, Wang JM. 2014. Study on the acid resistant properties of bio-based nylon 56 fiber compared with the fiber of nylon 6 and nylon 66. Adv Mater Res 1048:57–61. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1048.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nikel PI, de Lorenzo V. 2018. Pseudomonas putida as a functional chassis for industrial biocatalysis: from native biochemistry to trans-metabolism. Metab Eng 50:142–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nogales J, Palsson BØ, Thiele I. 2008. A genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of Pseudomonas putida KT2440: iJN746 as a cell factory. BMC Syst Biol 2:79. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sohn SB, Kim TY, Park JM, Lee SY. 2010. In silico genome-scale metabolic analysis of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis, degradation of aromatics and anaerobic survival. Biotechnol J 5:739–750. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jullesson D, David F, Pfleger B, Nielsen J. 2015. Impact of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering on industrial production of fine chemicals. Biotechnol Adv 33:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Silva-Rocha R, Martínez-García E, Calles B, Chavarría M, Arce-Rodríguez A, de Las Heras A, Páez-Espino AD, Durante-Rodríguez G, Kim J, Nikel PI, Platero R, de Lorenzo V. 2013. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D666–D675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Calero P, Nikel PI. 2019. Chasing bacterial chassis for metabolic engineering: a perspective review from classical to non-traditional microorganisms. Microb Biotechnol 12:98–124. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luengo JM, Olivera ER. 2020. Catabolism of biogenic amines in Pseudomonas species. Environ Microbiol 22:1174–1192. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shen CR, Lan EI, Dekishima Y, Baez A, Cho KM, Liao JC. 2011. Driving forces enable high-titer anaerobic 1-butanol synthesis in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:2905–2915. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03034-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.King ZA, Feist AM. 2014. Optimal cofactor swapping can increase the theoretical yield for chemical production in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng 24:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu X, Liu C, Qin B, Li N, Li X. March 2018. Preparation of cadaverine. US patent 9,919,996.

- 76.Xu G, Zha J, Cheng H, Ibrahim MHA, Yang F, Dalton H, Cao R, Zhu Y, Fang J, Chi K, Zheng P, Zhang X, Shi J, Xu Z, Gross RA, Koffas MAG. 2019. Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum for the de novo biosynthesis of tailored poly-γ-glutamic acid. Metab Eng 56:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dong H, Liffland S, Hillmyer MA, Chang MC. 2019. Engineering in vivo production of α-branched polyesters. J Am Chem Soc 141:16877–16883. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b08585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goswami A, Van Lanen SG. 2015. Enzymatic strategies and biocatalysts for amide bond formation: tricks of the trade outside of the ribosome. Mol Biosyst 11:338–353. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00627e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kino K, Arai T, Arimura Y. 2011. Poly-alpha-glutamic acid synthesis using a novel catalytic activity of RimK from Escherichia coli K-12. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:2019–2025. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02043-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hollenhorst MA, Clardy J, Walsh CT. 2009. The ATP-dependent amide ligases DdaG and DdaF assemble the fumaramoyl-dipeptide scaffold of the dapdiamide antibiotics. Biochemistry 48:10467–10472. doi: 10.1021/bi9013165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hollenhorst MA, Bumpus SB, Matthews ML, Bollinger JM Jr, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. 2010. The nonribosomal peptide synthetase enzyme DdaD tethers N(β)-fumaramoyl-l-2,3-diaminopropionate for Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent epoxidation by DdaC during dapdiamide antibiotic biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 132:15773–15781. doi: 10.1021/ja1072367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hara R, Hirai K, Suzuki S, Kino K. 2018. A chemoenzymatic process for amide bond formation by an adenylating enzyme-mediated mechanism. Sci Rep 8:2950. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fawaz MV, Topper ME, Firestine SM. 2011. The ATP-grasp enzymes. Bioorg Chem 39:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Attwood PV. 1995. The structure and the mechanism of action of pyruvate carboxylase. Int J Biochem Cell B 27:231–249. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(94)00087-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Becker J, Zelder O, Häfner S, Schröder H, Wittmann C. 2011. From zero to hero-design-based systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for l-lysine production. Metab Eng 13:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]