Abstract

Background

Colorectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are the most common NETs of the gastrointestinal tract. Due to the rarity, colorectal NETs are understudied and are not clearly understood. Our study sought to identify the factors associated with worse outcomes for colorectal NETs following resection.

Methods

We identified patients diagnosed with colorectal NETs [2004–2014] who underwent resection from the National Cancer Data Base. Non-NETs were excluded. Overall survival (OS) was evaluated using the Kaplan Meier method. Cox proportional hazards and logistic regression models were used to assess factors associated with radical versus local resection, OS and LOS.

Results

A total of 7,967 colon and 11,929 rectal NETs were analyzed. The majority of colon (93.4%) and rectal (89.1%) NETs underwent radical and local resection respectively. The 5-year OS was 69% and 92% for colon and rectal NETs respectively. Older age (OR 1.45, CI 1.37–1.53) and clinical stage 4 (OR 9.91, CI 4.56–21.52) were associated with higher odds for colonic radical resection. Lowest median income quartile (OR 1.41, CI 1.21–1.64) and African Americans (OR 1.26, CI 1.07–1.49) experienced higher mortality for colon and rectal NETs respectively.

Conclusions

Racial minority and low-income patients experience worse outcomes for colorectal NETs following resection.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine neoplasms, neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), colorectal cancer, radical resection, endoscopic resection, outcomes, National Cancer Data Base

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogenous group of malignancies that arise from the cells of the neuroendocrine system. Although these cells are distributed throughout the body, the most common site of disease is the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (1). Rectal NETs account for up to 27% of all NETs and 20% of gastrointestinal NETs (2-4). Colon NETs, which are less frequent, account for only 9.6% of all NETs and 14.1% of gastrointestinal NETs (2-8). Due to the rarity of these tumors, colorectal NETs are understudied and are not clearly understood. Additionally, advances in screening endoscopy and increased detection rates have resulted in an increase in the incidence of colorectal NETs in recent years (9-12), thus increasing the burden of this disease in the general population as well as demanding greater attention than in the past.

Although rectal NETs are more common, they exhibit a more favorable prognosis. Prior large US population-based studies reported a 5-year cancer-specific survival of 87.5–89.9% for localized rectal NETs (3-5). In contrast, colon NETs displayed the worst prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of between 23% and 42% in the 1990s (5,8,13). The poor prognosis of colon NETs has been attributed to the larger tumor size, earlier nodal involvement or metastasis, and poorer histologic differentiation of this subset of gastrointestinal NETs (8,14). Regardless of the location, clinicopathologic characteristics of gastrointestinal NETs, such as tumor size, tumor depth and lymph node metastases, are well documented determinants of treatment modality and outcomes (15,16). Prior studies suggest that small sized colorectal NETs (<10 mm) and without lymph node involvement can be safely treated with local resection, while larger tumors with size >10 mm or those with lymphatic invasion would require radical resection (2,6,10,17,18). Additionally, the presence of metastases is associated with worse patient outcomes and poor survival (2,17). However, there is a paucity of data regarding the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent radical and local resections for colorectal NETs. It is also not currently clear if chemotherapy has an impact on outcomes for patients who undergo resection. Additionally, the impact of baseline patient social and demographic characteristics on treatment modality and patient outcomes are not clearly understood.

To address these issues, our study sought to identify the patient-related factors associated with radical versus local resection for colon and rectal NETs in a national cohort of patients. We also sought to determine how these factors influence patient outcomes for colon and rectal NETs following resection. We hypothesized that treatment modality (i.e., radical versus local resection), and patient outcomes such as mortality and hospital length of stay are influenced by pertinent patient social and demographic characteristics. We present the following article in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting checklist (19) (available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-193).

Methods

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The CoC’s NCDB and the hospital participating in the CoC NCDB are the source of the de-identified data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors. The NCDB is a national cancer registry which captures 70% of all new cancer diagnoses in the United States from 1,500 cancer facilities and collects patient demographics and tumor and treatment characteristics. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was exempt from IRB review and patients’ informed-consent due to its use of de-identified data.

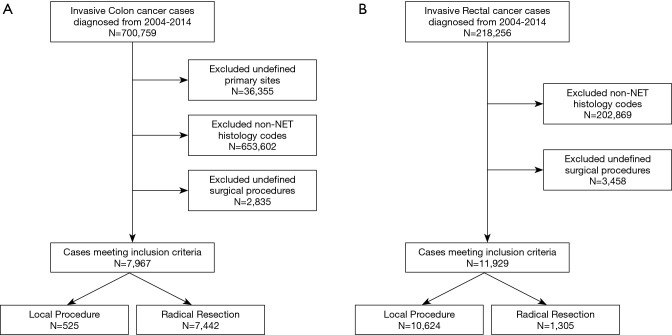

We identified patients diagnosed with invasive colon and rectal cancer between 2004 and 2014 who underwent a surgical resection from the National Cancer Data Base. We excluded patients diagnosed with a non-NET histology as well as those who did not undergo a local or radical resection (Figure 1A,B). Variables included in analysis were patient demographics (age, sex, race, Spanish/Hispanic origin, Charlson-Deyo score, primary payer, income, and education), treatment characteristics (resection type and chemotherapy), and tumor characteristics (clinical stage, surgical margins, and both number of lymph nodes examined and number of positive lymph nodes).

Figure 1.

(A) Flow chart of inclusion/exclusion criteria among colon cancer cases. (B) Flow chart of inclusion/exclusion criteria among rectal cancer case.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics and treatment and tumor characteristics were described within each tumor site. Categorical variables were described as number and percentage and continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR). Overall survival (OS) was evaluated from time of resection to death or last follow-up using the Kaplan Meier method. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess factors associated with OS and length of stay. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate factors associated with radical versus local resection and those having 12+ lymph nodes removed. All multivariable models were stratified by tumor site. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Colon NETs

A total of 7,967 NETs of the colon were identified and analyzed. Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the median year of diagnosis was 2010 and the median age at diagnosis was 58 y (IQR, 47–69 y). The majority of patients were females (56.9%). Most of the patients (85.3%) were Caucasian, with 12.3% African American, and 2.3% of another racial group. Private insurance (54.1%) and Medicare (34.6%) were the most frequent payer types, although 6.2% of patients had Medicaid, and 4.1% were uninsured. The proportion of patients whose community’s median income of $63,000 or greater was 35.4%, and 16.1% had a median income of less than $38,000. Additionally, 26.7% of patients resided in communities in which less than 7% residents had no high school degree and 14.5% in communities where the percentage with no high school degree was 21% or more. The majority of patients (86.3%) resided in metro areas, with 11.9% in urban areas, and only 1.7% in rural areas.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics among neuroendocrine tumors.

| Characteristic | Colon (N=7,967) | Rectum (N=11,929) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| N | 7,967 | 11,929 |

| Mean (SD) | 57.0 (16.7) | 55.4 (11.6) |

| Median | 58.0 | 54.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 47.0, 69.0 | 50.0, 62.0 |

| Range | (18.0–90.0) | (18.0–90.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 3,430 (43.1%) | 5,632 (47.2%) |

| Female | 4,537 (56.9%) | 6,297 (52.8%) |

| Race | ||

| Missing | 86 | 287 |

| White | 6,726 (85.3%) | 7,106 (61.0%) |

| Black | 970 (12.3%) | 3,477 (29.9%) |

| Other | 185 (2.3%) | 1,059 (9.1%) |

| Spanish/Hispanic origin | ||

| Missing | 449 | 799 |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Spanish | 7,159 (95.2%) | 10,191 (91.6%) |

| Hispanic/Spanish | 359 (4.8%) | 939 (8.4%) |

| Charlson-Deyo Score | ||

| 0 | 6,287 (78.9%) | 10,147 (85.1%) |

| 1 | 1,299 (16.3%) | 1,431 (12.0%) |

| 2+ | 381 (4.8%) | 351 (2.9%) |

| Primary payer | ||

| Missing | 123 | 218 |

| No insured | 324 (4.1%) | 395 (3.4%) |

| Private insurance | 4,241 (54.1%) | 7,657 (65.4%) |

| Medicaid | 483 (6.2%) | 887 (7.6%) |

| Medicare | 2,715 (34.6%) | 2,584 (22.1%) |

| Other government | 81 (1.0%) | 188 (1.6%) |

| Percent no high school degree | ||

| Missing | 77 | 81 |

| 21% or more | 1,143 (14.5%) | 2,401 (20.3%) |

| 13% to 20.9% | 1,961 (24.9%) | 3,128 (26.4%) |

| 7% to 12.9% | 2,680 (34.0%) | 3,577 (30.2%) |

| Less than 7% | 2,106 (26.7%) | 2,742 (23.1%) |

| Median income quartiles | ||

| Missing | 82 | 86 |

| Less than $38,000 | 1,272 (16.1%) | 2,378 (20.1%) |

| $38,000 to $47,999 | 1,691 (21.4%) | 2,547 (21.5%) |

| $48,000 to $62,999 | 2,129 (27.0%) | 3,034 (25.6%) |

| $63,000+ | 2,793 (35.4%) | 3,884 (32.8%) |

| Urban/rural | ||

| Missing | 248 | 380 |

| Metro | 6,664 (86.3%) | 10,425 (90.3%) |

| Urban | 921 (11.9%) | 1,000 (8.7%) |

| Rural | 134 (1.7%) | 124 (1.1%) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| N | 7,967 | 11,929 |

| Mean (SD) | 2,009.8 (3.2) | 2,009.5 (3.1) |

| Median | 2,010.0 | 2,010.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 2,007.0, 2,013.0 | 2,007.0, 2,012.0 |

| Range | (2,004.0–2,014.0) | (2,004.0–2,014.0) |

| Clinical stage | ||

| Missing | 5,201 | 7,318 |

| Stage 0 | 18 (0.7%) | 46 (1.0%) |

| Stage 1 | 923 (33.4%) | 4,106 (89.0%) |

| Stage 2 | 461 (16.7%) | 202 (4.4%) |

| Stage 3 | 514 (18.6%) | 119 (2.6%) |

| Stage 4 | 850 (30.7%) | 138 (3.0%) |

| Clinical T Stage | ||

| Missing | 5,601 | 7,333 |

| T0 | 123 (5.2%) | 59 (1.3%) |

| T1 | 882 (37.3%) | 4,101 (89.2%) |

| T2 | 359 (15.2%) | 236 (5.1%) |

| T3 | 693 (29.3%) | 157 (3.4%) |

| T4 | 309 (13.1%) | 43 (0.9%) |

| Clinical N Stage | ||

| Missing | 3,963 | 5,981 |

| N0 | 3,071 (76.7%) | 5,767 (97.0%) |

| N1 | 743 (18.6%) | 155 (2.6%) |

| N2 | 190 (4.7%) | 26 (0.4%) |

| Clinical M Stage | ||

| Missing | 555 | 719 |

| M0 | 6,555 (88.4%) | 11,069 (98.7%) |

| M1 | 857 (11.6%) | 141 (1.3%) |

| Surgical procedure type | ||

| Local | 525 (6.6%) | 10,624 (89.1%) |

| Radical resection | 7,442 (93.4%) | 1,305 (10.9%) |

| Surgical margins | ||

| Missing | 271 | 2,234 |

| No residual tumor | 6,777 (88.1%) | 8,469 (87.4%) |

| Residual tumor | 919 (11.9%) | 1,226 (12.6%) |

| Number of regional lymph nodes examined | ||

| N | 7,785 | 11,589 |

| Mean (SD) | 13.2 (11.5) | 1.0 (4.8) |

| Median | 13.0 | 0.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 3.0, 19.0 | 0.0, 0.0 |

| Range | (0.0–90.0) | (0.0–90.0) |

| Number of positive nodes (among those with at least 1 positive node) | ||

| N | 4,123 | 426 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.5 (5.5) | 6.2 (9.4) |

| Median | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 2.0, 7.0 | 2.0, 7.0 |

| Range | (1.0–78.0) | (1.0–88.0) |

The majority of patients (78.9%) had no comorbidities, 16.3% had a Charlson-Deyo Score of 1, and 4.8% with a score of 2 or higher. The clinical stage of the colon tumor was Stage 0 in 0.7% of cases, Stage 1 in 33.4%, Stage 2 in 16.7%, Stage 3 in 18.6%, and Stage 4 in 30.7%. The primary colon tumor was T0 in 5.2%, T1 in 37.3%, T2 in 15.2%, T3 in 29.3%, and T4 in 13.1% of cases. Nodal involvement was absent in 76.7% of colon tumors, N1 in 18.6%, and N2 in 4.7%. Distant metastasis was present in 11.6% of colon tumors. The majority (93.4%) of colon NETs underwent radical resection, with residual tumor present in 11.9%. The median number of regional lymph nodes examined was 13 (IQR, 3–19); 66.9% of patients with nodes examined had positive nodes with a median number of 4 (IQR, 2–7) nodes positive.

Rectal NETs

A total of 11,929 rectal NETs were identified and analyzed. Demographic and clinical characteristics are also summarized in Table 1. Overall, the median year of diagnosis was 2010 and the median age at diagnosis was 54 y (IQR, 50–62 y). The majority of patients were females (52.8%). Most of the patients (61.0%) were Caucasian, with 29.9% African Americans, and 9.1% of another racial group. Private insurance (65.4%) and Medicare (22.1%) were the most frequent payer types, while 7.6% of patients had Medicaid, and 3.4% were uninsured. The proportion of patients with a median income of $63,000 or greater was 32.8%, and 20.1% had a median income of less than $38,000. Additionally, 23.1% of patients resided in communities with less than 7% percentage with no high school degree, and 20.3% in communities where the percentage with no high school degree was 21% or more. The majority of patients (90.3%) resided in metro areas, with 8.7% in urban areas, and only 1.1% in rural areas.

The majority of rectal NETs were clinical Stage 1 (89.0%). Other clinical stages included Stage 0 in 1.0%, Stage 2 in 4.4%, Stage 3 in 2.6%, and Stage 4 in 3.0%. The primary rectal tumor was T0 in 1.3% of patients, T1 in 89.2%, T2 in 5.1%, T3 in 3.4%, and T4 in 0.9%. Nodal involvement was absent in 97.0% of rectal tumors, N1 in 2.6%, and N2 in 0.4%. Distant metastasis was present in only 1.3% of rectal tumors. The majority (89.1%) of rectal NETs underwent local resection, with residual tumor present in 12.6%. The majority of rectal NETs did not have lymph nodes examined. Of those who had at least 1 nodes examined, 53.1% had positive nodes with a median number of 3 (IQR, 2–7) positive lymph nodes.

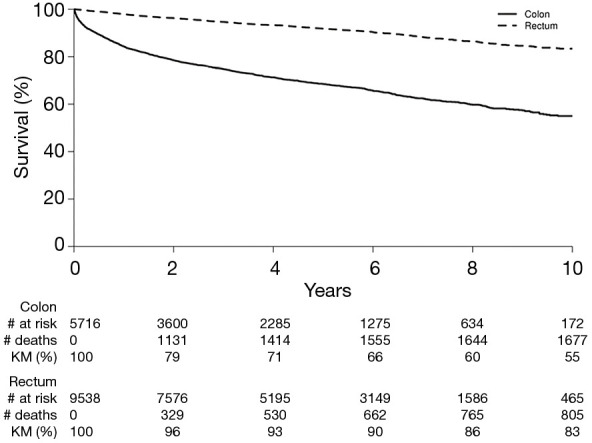

OS

Figure 2 shows the OS for colon and rectal NET patients respectively. The 5- and 10-year OS for colon NETs were 69% and 55% respectively. OS for rectal NETs was 92% at 5 years and 83% at 10 years.

Figure 2.

Overall survival for colorectal NETs.

Factors associated with radical versus local resection for NETs

On multivariable logistic regression modeling for tumor type (Table 2), an older age (OR 1.45, CI 1.37–1.53) was associated with higher odds for radical resection in colon NETs. Patients who had primary colon tumor with clinical Stage 2 (OR 3.83, CI 2.30–6.37), Stage 3 (OR 8.19, CI 3.96–16.92), and Stage 4 (OR 9.91, CI 4.56–21.52) had greater odds for radical resection than those with Stage 1 disease. Treatment with chemotherapy (OR 6.28, CI 3.32–11.88) was associated with significantly higher odds of radical resection for colon NETs than absence of chemotherapy.

Table 2. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with radical versus local resection among neuroendocrine tumors.

| Variable | Colon multivariable OR (95% CI) | P value | Rectum multivariable OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.45 (1.37, 1.53) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.0, 1.11) | 0.068 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) | 0.547 | 1.05 (0.92, 1.19) | 0.466 |

| Female | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Race | Overall 0.157 | Overall 0.007 | ||

| White | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Black | 1.36 (0.99, 1.87) | 0.058 | 0.75 (0.64, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.25 (0.69, 2.28) | 0.469 | 0.91 (0.73, 1.14) | 0.423 |

| Unknown | 0.69 (0.34, 1.42) | 0.314 | 0.90 (0.59, 1.35) | 0.604 |

| Median income quartiles | Overall 0.628 | Overall 0.411 | ||

| Less than 38,000 | 1.11 (0.83, 1.49) | 0.482 | 0.84 (0.69, 1.03) | 0.087 |

| 38,000–47,999 | 0.87 (0.68, 1.12) | 0.278 | 0.95 (0.79, 1.13) | 0.535 |

| 48,000–62,999 | 1.02 (0.80, 1.29) | 0.880 | 0.99 (0.84, 1.17) | 0.913 |

| 63,000+ | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Unknown | 0.90 (0.32, 2.58) | 0.847 | 1.26 (0.65, 2.45) | 0.498 |

| Clinical stage group | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| Stage 0 | 1.39 (0.31, 6.19) | 0.670 | 1.47 (0.58, 3.72) | 0.416 |

| Stage 1 | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Stage 2 | 3.83 (2.30, 6.37) | <0.001 | 6.12 (4.37, 8.58) | <0.001 |

| Stage 3 | 8.19 (3.96, 16.92) | <0.001 | 44.78 (24.49, 81.88) | <0.001 |

| Stage 4 | 9.91 (4.56, 21.52) | <0.001 | 10.17 (6.72, 15.39) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 2.72 (2.20, 3.35) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.18, 1.57) | <0.001 |

| Any chemotherapy | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| No | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Yes | 6.28 (3.32, 11.88) | <0.001 | 13.17 (9.76, 17.77) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.53 (0.96, 2.45) | 0.077 | 1.34 (1.02, 1.78) | 0.039 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

For patients with rectal NETs, African American patients (OR 0.75, CI 0.64–0.88) had lower odds of radical resection than Caucasians. Patients with clinical Stage 3 had the highest odds of radical resection (OR 44.78, CI 24.49–81.88). Also, clinical Stage 2 (OR 6.12, CI 4.37–8.58) or Stage 4 (OR 10.17, CI 6.72–15.39), or treatment with chemotherapy (OR 13.17, CI 9.76–17.77) were associated with higher odds of radical resection for rectal NETs.

Factors associated with mortality for NETs

On multivariable Cox proportional hazard modeling for tumor type (Table 3), radical resection (OR 1.70, CI 1.18–2.45), treatment with any chemotherapy (OR 2.31, CI 2.07–2.57), Stage 3 disease (OR 1.55, CI 1.12–2.15) or Stage 4 disease (OR 4.97, CI 3.72–6.62), lower median income quartiles (OR 1.41, CI 1.21–1.64 for less than $38,000), and an older age (OR 1.64, CI 1.57–1.70) were associated with higher mortality for colon NETs.

Table 3. Multivariable cox proportional hazards regression analysis of factors associated with death among neuroendocrine tumors.

| Variable | Colon multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P value | Rectum multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.64 (1.57, 1.70) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.77, 2.00) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.09 (0.99, 1.20) | 0.075 | 1.34 (1.16, 1.54) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Race | Overall 0.978 | Overall 0.002 | ||

| White | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Black | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 0.841 | 1.26 (1.07, 1.49) | 0.005 |

| Other | 0.93 (0.66, 1.32) | 0.698 | 0.67 (0.48, 0.94) | 0.021 |

| Unknown | 0.97 (0.61, 1.54) | 0.891 | 1.03 (0.60, 1.75) | 0.919 |

| Median income quartiles | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| Less than 38,000 | 1.41 (1.21, 1.64) | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.39, 2.13) | <0.001 |

| 38,000–47,999 | 1.24 (1.09, 1.42) | 0.001 | 1.42 (1.16, 1.74) | <0.001 |

| 48,000–62,999 | 1.10 (0.97, 1.25) | 0.136 | 1.24 (1.02, 1.52) | 0.032 |

| 63,000+ | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Unknown | 2.14 (1.54, 2.97) | <0.001 | 3.61 (2.20, 5.92) | <0.001 |

| Clinical stage group | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| Stage 0 | 0.81 (0.11, 5.85) | 0.834 | 4.76 (2.09, 10.85) | <0.001 |

| Stage 1 | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Stage 2 | 1.11 (0.77, 1.60) | 0.588 | 2.20 (1.46, 3.31) | <0.001 |

| Stage 3 | 1.55 (1.12, 2.15) | 0.009 | 1.64 (1.08, 2.49) | 0.021 |

| Stage 4 | 4.97 (3.72, 6.62) | <0.001 | 8.30 (5.88, 11.72) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.62 (1.23, 2.13) | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.05, 1.55) | 0.017 |

| Resection type | ||||

| Local | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Radical resection | 1.70 (1.18, 2.45) | 0.004 | 2.47 (2.06, 2.97) | <0.001 |

| Any chemotherapy | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| No | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Yes | 2.31 (2.07, 2.57) | <0.001 | 4.30 (3.34, 5.55) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.07 (0.86, 1.33) | 0.562 | 0.99 (0.70, 1.38) | 0.935 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Radical resection (OR 2.47, CI 2.06–2.97), treatment with any chemotherapy (OR 4.30, CI 3.34–5.55), lower median income quartiles (OR 1.72, CI 1.39–2.13 for less than $38,000), and an older age (OR 1.88, CI 1.77–2.00) were also associated with higher odds of death from rectal tumors. Additionally, male patients (OR 1.34, CI 1.16–1.54), and African Americans (OR 1.26, CI 1.07–1.49) had higher odds of death from rectal NETs than females and Caucasians respectively. Other racial groups had lower odds of death than Caucasians (OR 0.67, CI 0.48–0.94).

Factors associated with twelve or more lymph nodes examination following radical resection

Lymph nodes were more likely to be examined during radical resection of colon NETs if the patient had clinical Stage 3 disease (OR 1.56, CI 1.16–2.10) or received chemotherapy (OR 1.67, CI 1.44–1.94). An older age (OR 0.89, CI 0.86–0.93) and lower median income quartiles (OR 0.77, CI 0.65–0.91 for less than $38,000) were associated with lower odds of lymph node examination in colon NET patients who underwent radical resection (Table S1). Among rectal NET patients who underwent radical resection, clinical Stage 3 (OR 2.14, CI 1.15–3.99) and Stage 4 (OR 3.15, CI 1.50–6.61) were associated with higher odds of lymph node examination.

Table S1. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with 12+ lymph nodes examined among neuroendocrine tumors who underwent radical resection*.

| Variable | Colon multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P value | Rectum multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.89 (0.86, 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) | 0.316 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.92 (0.83, 1.03) | 0.159 | 0.93 (0.68, 1.27) | 0.659 |

| Female | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Race | Overall 0.405 | Overall 0.562 | ||

| White | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Black | 0.89 (0.75, 1.05) | 0.160 | 1.11 (0.74, 1.66) | 0.619 |

| Other | 0.82 (0.56, 1.20) | 0.296 | 1.60 (0.83, 3.09) | 0.164 |

| Unknown | 1.01 (0.58, 1.79) | 0.964 | 1.15 (0.37, 3.55) | 0.813 |

| Median income quartiles | Overall 0.024 | Overall 0.338 | ||

| Less than 38,000 | 0.77 (0.65, 0.91) | 0.003 | 0.96 (0.58, 1.59) | 0.881 |

| 38,000–47,999 | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) | 0.017 | 0.67 (0.43, 1.03) | 0.070 |

| 48,000–62,999 | 0.93 (0.80, 1.07) | 0.322 | 0.76 (0.50, 1.15) | 0.195 |

| 63000+ | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Unknown | 0.87 (0.52, 1.47) | 0.604 | 0.61 (0.18, 2.12) | 0.441 |

| Clinical stage group | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| Stage 0 | 2.38 (0.52, 10.94) | 0.267 | 0.31 (0.03, 3.16) | 0.325 |

| Stage 1 | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Stage 2 | 1.36 (0.99, 1.85) | 0.056 | 1.80 (0.91, 3.56) | 0.091 |

| Stage 3 | 1.56 (1.16, 2.10) | 0.003 | 2.14 (1.15, 3.99) | 0.017 |

| Stage 4 | 1.06 (0.82, 1.39) | 0.652 | 3.15 (1.50, 6.61) | 0.003 |

| Unknown | 0.95 (0.77, 1.18) | 0.665 | 1.02 (0.65, 1.60) | 0.934 |

| Any chemotherapy | Overall <0.001 | Overall 0.712 | ||

| No | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Yes | 1.67 (1.44, 1.94) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.69, 1.47) | 0.981 |

| Unknown | 1.10 (0.86, 1.40) | 0.446 | 1.34 (0.67, 2.67) | 0.414 |

*, among patients with at least 1 node examined. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Factors associated with short hospital stay following radical resection

Table S2 shows the factors associated with a short hospital stay following radical resection. Colon NETs patients who underwent radical resection were less likely to experience a short hospital stay if they were older (OR 0.82, CI 0.80–0.84), male (OR 0.91, CI 0.86–0.96), African Americans (OR 0.82, CI 0.75–0.90), earned lower incomes (OR 0.84, CI 0.77–0.92 for less than $38,000), or had clinical Stage 2 (OR 0.83, CI 0.74–0.94), Stage 3 (OR 0.82, CI 0.74–0.91) or Stage 4 (OR 0.56, CI 0.50–0.62) disease. Patients with rectal NETs who underwent radical resection had lower odds of a short hospital stay if they were older (OR 0.94, CI 0.90–0.99), male (OR 0.86, CI 0.75–0.98), had clinical Stage 2 (OR 0.67, CI 0.48–0.92), Stage 3 (OR 0.48, CI 0.38–0.61) or Stage 4 (OR 0.41, CI 0.31–0.56) disease, or received chemotherapy (OR 0.75, CI 0.62–0.91).

Table S2. Multivariable cox proportional hazards regression analysis of factors associated with short los among neuroendocrine tumors who underwent radical resection.

| Variable | Colon multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P value | Rectum multivariable, OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.82 (0.80, 0.84) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.030 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) | 0.001 | 0.86 (0.75, 0.98) | 0.027 |

| Female | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Race | Overall <0.001 | Overall 0.735 | ||

| White | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Black | 0.82 (0.75, 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) | 0.312 |

| Other | 0.83 (0.68, 1.00) | 0.052 | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) | 0.729 |

| Unknown | 0.86 (0.66, 1.13) | 0.281 | 0.99 (0.63, 1.55) | 0.967 |

| Median income quartiles | Overall <0.001 | Overall 0.461 | ||

| Less than 38,000 | 0.84 (0.77, 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.71, 1.10) | 0.266 |

| 38,000–47,999 | 0.88 (0.81, 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.69, 1.01) | 0.066 |

| 48,000–62,999 | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | 0.021 | 0.91 (0.76, 1.08) | 0.282 |

| 63,000+ | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Unknown | 0.77 (0.59, 1.00) | 0.054 | 0.91 (0.49, 1.68) | 0.759 |

| Pathologic stage group | Overall <0.001 | Overall <0.001 | ||

| Stage 0 | 1.16 (0.53, 2.58) | 0.708 | 0.46 (0.20, 1.02) | 0.057 |

| Stage 1 | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Stage 2 | 0.83 (0.74, 0.94) | 0.003 | 0.67 (0.48, 0.92) | 0.014 |

| Stage 3 | 0.82 (0.74, 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.38, 0.61) | <0.001 |

| Stage 4 | 0.56 (0.50, 0.62) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.31, 0.56) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 0.78 (0.71, 0.86) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) | 0.301 |

| Any chemotherapy | Overall 0.416 | Overall 0.007 | ||

| No | 1.0 reference | 1.0 reference | ||

| Yes | 0.96 (0.88, 1.03) | 0.257 | 0.75 (0.62, 0.91) | 0.003 |

| Unknown | 1.03 (0.91, 1.17) | 0.599 | 1.09 (0.80, 1.49) | 0.574 |

Discussion

This study sought to identify patient level factors associated with radical versus local resection for colon and rectal NETs, and to determine how these factors influence patient outcomes following resection in a national cohort of patients. We found that a significant proportion (93%) of colon NET patients underwent radical resection while the majority of those with rectal NETs (89%) underwent local resection. Patients with advanced clinical stage disease, or those treated with any chemotherapy had significantly higher odds of undergoing radical resection regardless of tumor site. Radical resection, African American race, advanced disease, chemotherapy, low income or old age were associated with a significantly higher mortality. Finally, African Americans and low-income patients were also more likely to experience a longer hospital stay following a radical resection.

Interestingly, age was an important determinant of incidence and mortality from colorectal NETs in our study. The median age of incidence for colon NETs in our study was 58 and 54 years in the rectal NETs. The higher incidence of colon NETs, which are more likely to be high grade, in addition to other possible co-existent comorbidities likely explain the higher mortality observed in older populations from colorectal NETs. Similar to our study, Reeders et al. found an older age (>65 years) to be associated with an increased risk for NET related mortality (20). Scherübl and colleagues reported a similar observation for pancreatic NETs (21).

In a recent large population based national study in the US, the proportion (89%) of rectal NET patients with tumors <2 cm who underwent local resection was similar to what we found (4). The aforementioned study demonstrated that early-stage tumors without aggressive biologic characteristics (e.g., large tumor size, early nodal involvement or poor histologic differentiation) could be preferably treated with local resection due to increased morbidity and mortality associated with radical resection similar to our findings (4). In contrast, the vast majority of colon NETs are discovered at an advanced stage [as high grade NETs or as neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs)] and a more aggressive treatment with radical resection is recommended (13). Unsurprisingly, the majority (93%) of colon NETs in our study were treated with radical resection. Additionally, we found that the OS for colon NETs (69% at 5 y and 55% at 10 y) was significantly lower than survival for their rectal counterparts (92% at 5 y and 83% at 10 y), likely due to the increased aggressiveness of colon NETs. Although the survival rates observed in our study are similar to the rates reported by recent retrospective cohort studies (2,4,6,10,16,22), they are significantly higher than those observed in the 1990s or earlier (3,5,13,14). Scherübl et al. observed a 20% increase in the overall 5-year survival of patients with rectal NETs during a 35-year study period in the US (9). The improvement in survival may represent advances in diagnostic technology, earlier diagnosis and increased awareness about colorectal NETs compared to previous decades. Increasing the proportion of colon NETs diagnosed early through screening colonoscopy therefore could potentially improve OS even further.

The clinicopathologic characteristics that influence outcomes for colorectal NETs are well documented. Clinicopathologic characteristics such as tumor size, tumor depth, and lymphatic involvement have been identified as important determinants of treatment choice for colorectal NETs (15,23). The aforementioned studies demonstrated that the larger sized neoplasms and those with lymphatic invasion would require radical resection for optimal management. Our study emphasizes the importance of the interplay between patient demographics and clinical characteristics in determining treatment patterns and patient outcomes. Interestingly, our study suggests that older patients are more likely to undergo radical resection. This is likely due to a higher prevalence of these tumors in the older population. Based on the findings of our study, colon NETs were diagnosed later in life on average than their rectal counterparts and were associated with a higher proportion of advanced disease and were more likely to undergo a radical resection. These findings are likely explained by the pathologic attributes of these tumors which tend to be larger, with a poorer differentiation or higher malignant potential than rectal NETs, thus necessitating radical resection (8,14).

Furthermore, although rectal NETs are less aggressive and exhibit a more favorable prognosis (3-5), we found that they have a higher mortality in African American or male patients than White or female patients. In another large population based study which analyzed patient data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database, the age-adjusted incidence rates of NETs for all sites were highest in African American males (4.48 per 100,000 population per year) (5). Modlin et al. found that rectal NETs were over-represented among African American and Asian populations within the US, suggesting a possible role of genetics in the development of the disease (5). The high disease burden in African American male population may partly account for the proportionally higher rates of death in this population, but the reasons are not completely understood. Further research to investigate genetic or pathophysiologic pathways are therefore needed. African Americans and low income patients were also more likely to experience a longer hospital stay following radical resection for colon NETs, suggesting that socially deprived individuals may experience worse outcomes as compared to the others.

There is a paucity of data regarding the role of chemotherapy and its impact on patient outcomes for colorectal NETs. Although resection is the treatment of choice in patients who can tolerate an operation and who have operable disease, chemotherapy is an option for treatment of metastatic disease (24). We found that chemotherapy treatment was associated with higher rates of radical resection for both colon and rectal NETs. This is likely explained by the presence of a coexistent advanced (i.e., high grade NETs or poorly differentiated NECs) or metastatic disease in patients undergoing radical resection. We also found that the receipt of chemotherapy was associated with increased mortality from colorectal NETs regardless of site, and increased hospital length of stay following radical resection for rectal NETs. These findings are possibly due to the baseline severity of the disease as previously discussed, although the role other factors or mechanisms that have not been established by this study cannot be discounted.

Our study is novel for demonstrating the interplay between patient social, racial and clinical characteristics in influencing treatment modality as well as patient outcomes for colorectal NETs. Although the clinicopathologic characteristics that determine treatment choice and outcomes are extensively studied, differences in treatment and patient outcomes based on patient social and racial characteristics are not well established. Overall, our study suggests that social and racial characteristics such as age, gender, race and income are important determinants of treatment type and outcomes for colorectal NETs. These findings are strengthened by the use of a large national cancer database which increases the generalizability to the general population. There are important limitations to the study as well. The majority of the patients included in our study were from metro areas and therefore, this limits the generalizability of our study to rural-based populations. The retrospective nature of our study limits our interpretations to associations since no causal relationship can be established. For example, it is unclear if factors outside the scope of this study such as genetic or pathophysiologic mechanisms account for the worse outcomes demonstrated among racial minority such African Americans. The terminology and classification of NETs have evolved during the analyzed period of this study by the WHO 2017 NET classification. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, available data was used without reassessing the pathology specimen. This could have resulted in misclassified lesions. A significant number of cases were excluded (Figure 1A,B) due to undefined surgical procedures (i.e., local versus radical resections). It is unclear if excluded cases differ significantly from the cases analyzed in terms of social or demographic characteristics and outcomes. The TNM staging were not consistently documented for all patients in the database leading to a high rate of missing data for tumor staging. These patients were however included in the study due to availability of other data pertinent to the study objectives. The retrospective design also limits our ability to account for all possible factors that influence the choice of treatment and patient outcomes for our cohort. The study has not accounted for the modulating effect of factors external to the patient such as differences in treatment outcomes among hospital and case volumes. While these factors are important, our study focused on defining the patient social and demographic factors associated with treatment and outcomes for colorectal NETs.

Conclusions

Multiple factors influence the treatment and outcomes for patients with colorectal NETs. Clinicopathologic characteristics such as tumor size, tumor depth and lymphatic invasion are well documented determinants. The social and demographic factors that influence treatment and patient outcomes have not been adequately studied. We demonstrated that patient age, gender, race and income are important social and demographic determinants of treatment and outcomes in addition to clinicopathologic characteristics. Of note, older patients are more likely to undergo radical resection, while racial minority and low-income patients experience worse outcomes following resection.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank the American College of Surgeons Committee on Cancer for providing access to the Participant User File from the National Cancer Data Base. Disclaimers: The American College of Surgeons Committee on Cancer provided the Participant User File from the National Cancer Data Base, but has not reviewed or validated the results or conclusions of our study.

Funding: This work was supported by the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. ©2018 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was exempt from IRB review and patients’ informed-consent due to its use of de-identified data.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors present the study in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting checklist. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-193

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-193

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-193

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICJME uniform disclosure form (available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-193). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2011;40:1-18, vii. 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngamruengphong S, Kamal A, Akshintala V, et al. Prevalence of metastasis and survival of 788 patients with T1 rectal carcinoid tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:602-6. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maggard MA, O'Connell JB, Ko CY. Updated population-based review of carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg 2004;240:117-22. 10.1097/01.sla.0000129342.67174.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezekian B, Adam MA, Turner MC, et al. Local excision results in comparable survival to radical resection for early-stage rectal carcinoid. J Surg Res 2018;230:28-33. 10.1016/j.jss.2018.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003;97:934-59. 10.1002/cncr.11105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin HH, Lin JK, Jiang JK, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of colorectal carcinoid tumors and patient outcomes. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:366. 10.1186/1477-7819-12-366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colonoscopy Study Group of Korean Society of Coloproctology Clinical characteristics of colorectal carcinoid tumors. J Korean Soc Coloproctol 2011;27:17-20. 10.3393/jksc.2011.27.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray SE, Lloyd RV, Sippel RS, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of colonic carcinoid tumors. J Surg Res 2013;184:183-8. 10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherübl H. Rectal carcinoids are on the rise: early detection by screening endoscopy. Endoscopy 2009;41:162-5. 10.1055/s-0028-1119456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott FD, Heeney A, Courtney D, et al. Rectal carcinoids: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 2014;28:2020-6. 10.1007/s00464-014-3430-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray SE, Sippel RS, Lloyd R, et al. Surveillance of small rectal carcinoid tumors in the absence of metastatic disease. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3486-90. 10.1245/s10434-012-2442-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avenel P, McKendrick A, Silapaswan S, et al. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: an increasing incidence of rectal distribution. Am Surg 2010;76:759-63. 10.1177/000313481007600736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballantyne GH, Savoca PE, Flannery JT, et al. Incidence and mortality of carcinoids of the colon. Data from the Connecticut Tumor Registry. Cancer 1992;69:2400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spread C, Berkel H, Jewell L, et al. Colon carcinoid tumors. A population-based study. Dis Colon Rectum 1994;37:482-91. 10.1007/BF02076196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Natour RH, Saund MS, Sanchez VM, et al. Tumor size and depth predict rate of lymph node metastasis in colon carcinoids and can be used to select patients for endoscopic resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:595-602. 10.1007/s11605-011-1786-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasuga A, Chino A, Uragami N, et al. Treatment strategy for rectal carcinoids: A clinicopathological analysis of 229 cases at a single cancer institution. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1801-7. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, et al. Prognosis and risk factors of metastasis in colorectal carcinoids: results of a nationwide registry over 15 years. Gut 2007;56:863-8. 10.1136/gut.2006.109157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yangong H, Shi C, Shahbaz M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment experience of rectal carcinoid (a report of 312 cases). Int J Surg 2014;12:408-11. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495-9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeders J, Ashoka Menon V, Mani A, et al. Clinical Profiles and Survival Outcomes of Patients With Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors at a Health Network in New South Wales, Australia: Retrospective Study. JMIR Cancer 2019;5:e12849. 10.2196/12849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strosberg JR, Cheema A, Weber J, et al. Prognostic Validity of a Novel American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Classification for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3044-9. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleeson FC, Levy MJ, Dozois EJ, et al. Endoscopically identified well-differentiated rectal carcinoid tumors: impact of tumor size on the natural history and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:144-51. 10.1016/j.gie.2013.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii T, Tabe Y, Yajima R, et al. Transanal local excision in the treatment of rectal carcinoid: results and implications. Hepatogastroenterology 2011;58:1168-70. 10.5754/hge10123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrne RM, Pommier RF. Small Bowel and Colorectal Carcinoids. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2018;31:301-8. 10.1055/s-0038-1642054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]