Abstract

Background:

The administration of dexmedetomidine is limited to highly monitored care settings because it is only available for use in humans as an intravenous medication. An oral formulation of dexmedetomidine may broaden its use to all care settings. Therefore, we investigated the effect of a capsule-based solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine on sleep polysomnography.

Methods:

We performed a single-site, placebo-controlled randomized, cross-over, double-blind phase II study of a solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine (700mcg, n = 15). Our primary outcome was polysomnography sleep quality. Secondary outcomes included performance on the motor sequence task and psychomotor vigilance task administered to each subject at night and in the morning to assess motor memory consolidation and psychomotor function, respectively. Sleep questionnaires were also administered.

Results:

Oral dexmedetomidine increased the duration of non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) stage 2 sleep by 63 [95% CI: 19, 107] minutes (p = 0.010) and decreased the duration of REM sleep by 42 [5, 78] minutes (p = 0.031). Overnight motor sequence task performance improved after placebo sleep (7.9%, p = 0.003) but not after oral dexmedetomidine-induced sleep (−0.8%, p = 0.900). In exploratory analyses, we found a positive correlation between spindle density during non-REM stage 2 sleep and improvement in the overnight test performance (Spearman’s Rho = 0.57, p = 0.028, n = 15) for placebo but not oral dexmedetomidine (Spearman’s Rho = 0.04, p = 0.899, n = 15). Group differences in overnight motor sequence task performance, psychomotor vigilance task metrics, and sleep questionnaires did not meet our threshold for statistical significance.

Conclusions:

These results demonstrate that the nighttime administration of a solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine is associated with increased non-REM 2 sleep and decreased REM sleep. Spindle density during dexmedetomidine sleep was not associated with overnight improvement in the motor sequence task.

Keywords: dexmedetomidine, oral dosage, polysomnography, non-rapid eye movement sleep, delirium

INTRODUCTION

Dexmedetomidine is an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist sedative medication that patterns the activity of various arousal nuclei similar to sleep.1–7 We recently demonstrated that a night time loading dose of intravenous dexmedetomidine in healthy volunteers promotes non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) stage 3 sleep.8 A continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine in humans produces electroencephalogram spindle (13–16 Hz) and slow-delta (0.1–4 Hz) oscillations that approximate non-REM stage 2 sleep.9–13 Thus, in humans, dexmedetomidine may be administered to promote non-REM stage 2 or non-REM stage 3 sleep. However, dexmedetomidine-induced non-REM stage 2 and non-REM stage 3 sleep may depend on the pharmacokinetic profile associated with the route of administration or the timing of drug administration (i.e., nighttime versus daytime). Taken together, these data suggest that dexmedetomidine engages non-REM sleep circuits.

Dexmedetomidine is widely used in intensive care units as a sedative agent and as a pharmacological aid to reduce the incidence and duration of delirium.14–18 The administration of dexmedetomidine is limited to highly monitored care settings because it is only available for use as an intravenous medication. An oral formulation may broaden the use and benefits of dexmedetomidine to patients in general medical and surgical units. An oral formulation of dexmedetomidine may also provide evidence to support its use in patients with sleep onset or maintenance disorders. We note that the intravenous formulation of dexmedetomidine has been administered pre-operatively as an oral anxiolytic solution.19 However, whether an oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine has a sedative or sleep-promoting effect in humans is not clear.

Therefore, we investigated the effect of a capsule-based solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine in a phase II (n = 15) polysomnography study. Because oral dexmedetomidine is expected to more closely approximate a continuous infusion compared to a loading dose, we hypothesized that it would increase the duration of non-REM stage 2 sleep. Sleep spindles, a characteristic electroencephalogram feature of non-REM stage 2 sleep,11,20 have been associated with improved Motor Sequence Task (MST) performance (sleep-dependent memory consolidation).20 Therefore, we also hypothesized that the solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine would be associated with improved performance on the MST. Finally, we hypothesized that dexmedetomidine would not affect performance on the Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT).

METHODS

Ethics Statement

The Partners Human Research Committee approved this human research study conducted at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (2016P000269) and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov, (NCT02818569) on June 29, 2016 (Principal Investigator: Oluwaseun Akeju). This study was conducted under a Food and Drug Administration investigator-initiated Investigational New Drug Application (IND129461). A Data and Safety Monitoring Board was charged with the safety of study volunteers and that the scientific goals of the study were met.

Subject Selection

A Phase I dose-finding study (n =15) was first performed. The primary endpoint for the Phase I study was hemodynamic stability. Our Data and Safety Monitoring Board approved the use of 700 mcg for this Phase 2 sleep study. The maximum mean (SD) plasma concentration of this dose of oral dexmedetomidine was 0.38 (0.44) ng/mL. This occurred 120 mins after drug administration (half-life, 3.1 hours). The mean plasma concentration at the last sampling timepoint, which occurred 420 mins after drug administration was 0.14 (0.20) ng/mL. Subjects were recruited for this study between July 2017 and April 2018. A study flyer was disseminated through the Partners Public Affairs distribution list. Potential study participants contacted a clinical research coordinator who administered a questionnaire to confirm that the study inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. The following information was also verified by self-report: regular sleep-wake cycles, absence of naps or consumption of alcohol or caffeinated beverages before sleep, drug-free, and non-smoking status. Before potential enrollment, subjects underwent a complete medical history and standard pre-anesthesia assessment. Other procedures included a toxicology screen to rule out prohibited drug use, a pregnancy test for females, and an electrocardiogram to rule out cardiac conduction abnormalities. None of the subjects had any known history of sleep disorders or any physical or psychiatric illness. Written informed consent was obtained from a total of 16 right-handed subjects during the screening visit. One subject withdrew from participation before any experimental study visits due to scheduling conflicts. All subjects were American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status I.

Drug Allocation

Dexmedetomidine hydrochloride, USP, purchased from Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Company Limited (Jiangsu Province, China) was weighed in a laminar flow hood and packaged in oral capsules with an inert excipient. The placebo capsule contained only the inert excipient. The order of drug administration was determined by a computer-generated randomization schedule generated by the clinical trials pharmacist. Allocation concealment was ensured by the fact that dexmedetomidine and placebo capsules could not be distinguished based on appearance. The randomization key associated with each participant trial identification number remained with the clinical trial pharmacist for the duration of the study. All trial medications were labeled as “dexmedetomidine or placebo” to preserve the integrity of randomization assignments. The study nurse taking care of the subject administered the medications.

Polysomnography

This was a single-site, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized controlled, cross-over study to assess the effect of a 700mcg capsule-based solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine (n = 15) on objective and subjective measures of sleep quality. Study subjects were instructed to arrive at Massachusetts General Hospital at 17:00 hours to prepare for overnight polysomnography recording. Data were recorded using the Somté PSG (Compumedics, Charlotte, NC). Electroencephalogram (6 channels; 2 frontal, 2 central, 2 occipital), electrooculogram, and electromyogram were placed according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine practice standards. Each study subject underwent three polysomnography study visits, with the first visit serving to acclimate subjects to the sleep environment and polysomnography recording equipment. A urine toxicology screen was performed at each of three study visits to rule out the use of prohibited substances. Additionally, a urine pregnancy test was performed to rule out pregnancy in all female subjects.

After the acclimation night, subjects were randomly assigned to receive dexmedetomidine or placebo. We employed a Placebo-Dexmedetomidine/Dexmedetomidine-Placebo (2 periods, 2 treatments) design. Thus, all subjects received dexmedetomidine and placebo but on separate study visits. Our randomization procedure resulted in 7 subjects in the Placebo-Dexmedetomidine group, and 8 subjects were in the Dexmedetomidine-Placebo group. The experimental overnight polysomnography visits were separated by at least a 48-hour washout period. This washout period was based on the pharmacokinetic properties of dexmedetomidine. Immediately prior to lights outs, subjects were required to perform the PM MST (training) followed by the PM PVT (training). Drug administration followed by lights out occurred at 21:00 hours. Trained nursing staff monitored video surveillance, heart rate, and oxygen saturation levels overnight. Subjects were instructed to silence their electronic devices, and the use of cell phones throughout the night was strictly prohibited. Lights on occurred at 07:00 hours the next morning. Immediately after lights on, subjects were required to perform the AM MST (testing) followed by the AM PVT (testing). Polysomnography data were scored using a validated automated sleep scoring software.21 Sleep spindles were manually picked from a central electroencephalogram channel during non-REM stage 2 sleep in the spectral domain by a blinded investigator (S.M).22 This approach is sensitive to sleep spindles that are not easily discerned in the time-domain (i.e., due to low power).22

Motor sequence task

The MST has previously been described.23,24 The MST involves pressing four keys with the fingers of the left hand, repeating a five-digit sequence quickly and accurately for 30 seconds (Figure 1A). We employed different sequences (e.g., 4–1–3–2–4 and 1–4–2–3–1) for each sleep visit and their order was counterbalanced within groups. There is no known transfer of learning between sequences on this task.25 The sequence was displayed at the top of the screen, and dots appeared beneath it with each keystroke. During both training (evening) and testing (morning) sessions, participants alternated tapping and rest periods of 30 seconds each for a total of 12 tapping trials. MST performance was measured as the number of correctly typed five-digit sequences per trial. The primary dependent measure for the MST was overnight improvement that is calculated as the percent improvement in correct sequences from the average of the last three training trials to the average of the first three test trials.24,26

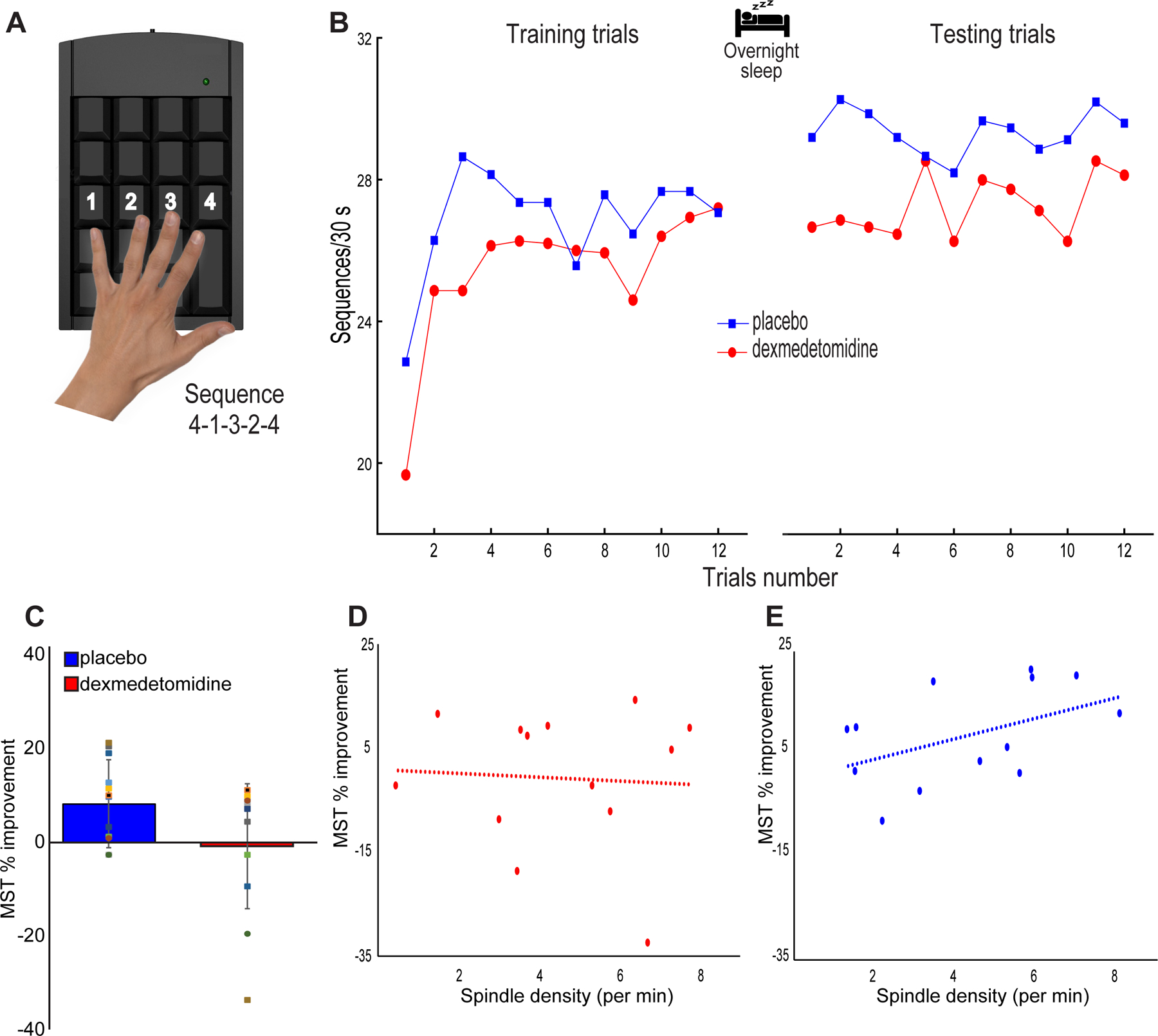

Fig. 1.

MST performance. (A) The Motor Sequence Task (MST) involves typing a 5-digit sequence (4–1–3–2–4) as quickly and correctly as possible for 12 rounds of 30 second intervals. (B) MST performance during both the placebo and dexmedetomidine study visits. Placebo visits showed visibly improved overnight performance (average of first three testing sequences - average of last three training sequences), whereas oral dexmedetomidine immediate performance appeared similar between training and testing sessions. (C) Improvement in MST performance (%) met our threshold for statistical significance for the placebo (p=0.003) but not for the dexmedetomidine (p=0.900) study visits. There were no statistically significant differences in immediate (p = 0.078) performance between groups. (D) Spindle density during non-REM stage 2 sleep and overnight MST improvement after oral dexmedetomidine were not correlated (Spearman’s Rho= 0.1, p = 0.748, n = 13; Spearman’s Rho= 0.1, p = 0.820, n = 15 after data imputation). (E) We confirmed the previously described24,26 positive correlation between spindle density during non-REM stage 2 sleep and overnight MST improvement post placebo (Spearman’s Rho= 0.54, p = 0.058, n = 13; Spearman’s Rho= 0.57, p = 0.028, n = 15 after data imputation).

Psychomotor vigilance task

The PVT was also administered. The PVT is a computerized reaction task that measures the response times to visual stimuli. These stimuli were presented at random intervals (between 2 to 10 seconds) for 10 minutes. Subjects were trained on the PVT before the onset of sleep and then tested in the morning. The primary dependent measures for the PVT were the number of responses that were longer than 400 milliseconds (lapse 400) and the mean response times.

Statistical Analysis

An apriori sample size calculation was not performed. Our sample size was approved by the Food and Drug Administration after they weighed potential risks and benefits and the results of our previous study. Data from the acclimation night visits were not analyzed. We analyzed differences between training and testing MST (PVT) measures using the two-sample paired T-test. For group level inferences, we analyzed polysomnography, sleep questionnaire, MST, PVT difference data using a statistical approach for the Placebo-Dexmedetomidine/Dexmedetomidine-Placebo (2 periods, 2 treatments) design. We first obtained individual paired difference for each metric. The paired differences were then used in a two-sample t-test to test the difference between the periods, which is equivalent to the treatment effect.

We computed Spearman Rho correlation between overnight MST improvement and spindle density (and spindle count) before and after data imputation (n = 2 data points were imputed for the dexmedetomidine and placebo visits, respectively). Imputed data are expectations conditional on the nonmissing data. The mean and covariance matrix, which was estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood approach, was used for the imputation calculation. Data imputation and all analyses were performed using JMP®, Pro 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007). All tests were two-sided with alpha = 0.05.

Results

Polysomnography

Oral dexmedetomidine biased the sleep architecture towards non-REM stage 2 Sleep

All subjects were required to lay in bed for 10 hours. One subject’s sleep data for the placebo visit was excluded from sleep stage analyses due to poor signal quality. Poor electrode contact was encountered several hours after sleep onset in a different subject during their placebo study visit, and in another subject during their oral dexmedetomidine study visit. Total time in bed and sleep times were similar between the groups (Table 1). However, dexmedetomidine increased non-REM stage 2 sleep by 63 [19, 107] minutes (p =0.010) and decreased REM sleep by 42 [5, 78] minutes (p =0.031). We analyzed the effect of oral dexmedetomidine on total sleep time (defined as the sum of all sleep stages) and found that it significantly increased the percentage of total sleep time spent in non-REM stage 2 sleep by 10 [4, 16] (p =0.005) percent and decreased REM sleep by 8 [1, 15] percent (p =0.026). These data are summarized in table 1. We did not find any significant differences in standard measures of sleep latency (Table 2), or measures of sleep stage switching (Table 3). We assessed sleep stage switching using number of stage shifts (switch) and number of shifts to a lighter stage (sleep fragmentation). We did not find significant differences in subjective measures of sleep quality (Table 4).

Table 1.

Sleep metrics derived from polysomnography

| Placebo (STD) | Dexmedetomidine (STD) | Diff (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dark time (mins) | 600 (0.3) | 600 (0.4) | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.2) | 0.422 |

| Total sleep time (mins) | 523 (40) | 544 (33) | −16 (−43, 11) | 0.207 |

| Sleep Efficiency (%) | 87 (7) | 91 (5) | −3 (−7, 2) | 0.211 |

| WASO (mins) | 53 (39) | 42 (29) | 5 (−19, 29) | 0.639 |

| Wake duration (min) | 77 (40) | 56 (33) | 16 (−11, 43) | 0.212 |

| N1 (mins) | 24 (13) | 24 (19) | 0.3 (−10, 11) | 0.953 |

| N2 (mins) | 256 (46) | 326 (69) | −63 (−107, −19) | 0.010 |

| N3 (mins) | 122 (32) | 108 (34) | 5 (−7, 18) | 0.362 |

| REM (mins) | 120 (27) | 86 (53) | 42 (5, 78) | 0.031 |

| N1 TST (%) | 5 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.2 (−2, 2) | 0.881 |

| N2 TST (%) | 49 (6) | 60 (11) | −10 (−16, −4) | 0.005 |

| N3 TST (%) | 24 (6) | 20 (6) | 2 (−0.2, 4) | 0.071 |

| REM TST (%) | 23 (6) | 16 (11) | 8 (1, 15) | 0.026 |

WASO, wake after sleep onset; N1, non-rapid eye movement stage 1; N2, non-rapid eye movement stage 2; N3, non-rapid eye movement stage 3; REM, rapid eye movement stage; TST, total sleep time. Diff, differences in the mean of the groups.

Table 2.

Sleep latencies derived from polysomnography

| Placebo (STD) | Dexmedetomidine (STD) | Diff (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep latency (mins) | 23.8 (18.4) | 12.6 (7.5) | 11.1 (−2.6, 24.7) | 0.101 |

| Wake duration (min) | 77.0 (40.2) | 55.6 (32.5) | 16 (−10.9, 42.9) | 0.212 |

| Sleep latency to N1 (mins) | 24.8 (18.6) | 13.0 (7.4) | 10.6 (−3.2, 24.4) | 0.117 |

| Sleep latency to N2 (mins) | 28.3 (18.4) | 21.0 (12.8) | 5.5 (−8.4, 19.4) | 0.395 |

| Sleep latency to N3 (mins) | 49.5 (27.0) | 34.8 (21.4) | −10.7 (−2, 23.4) | 0.089 |

| Sleep latency to REM (mins) | 70.6 (56.6) | 74.3 (88.4) | −7.4 (−96.1, 81.2) | 0.837 |

N1, non-rapid eye movement stage 1; N2, non-rapid eye movement stage 2; N3, non-rapid eye movement stage 3; REM, rapid eye movement stage; Diff, differences in the mean of the groups.

Table 3.

Sleep fragmentation and switch derived from PSG

| Placebo (STD) | Dexmedetomidine (STD) | Diff (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switch | 173.9 (44.7) | 170.2 (64.0) | 5.8 (−26.3, 38) | 0.690 |

| Switch index (per min) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.1) | 0.404 |

| Sleep fragmentation | 59.1 (15.5) | 58.7 (20.4) | 1.9 (−10.7, 14.5) | 0.746 |

| Sleep fragmentation index (per min) | 0.1 (0.01) | 0.1 (0.04) | 0.0 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.588 |

Switch, number of stage shifts; sleep fragmentation, number of shifts to a lighter stage; Diff, differences in the mean of the groups

Table 4.

Sleep metrics derived from questionnaire

| Placebo (STD) | Dexmedetomidine (STD) | Diff (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sleep (mins) | 521.3 (62.2) | 531.6 (59.5) | −16.9 (−44.2, 10.5) | 0.203 |

| Sleep latency (mins) | 36.3 (27.3) | 33 (24.4) | 5.9 (−10.3, 22.2) | 0.435 |

| Times awakened (n) | 3.7 (3) | 3.2 (2.6) | 0.9 (−1.1, 3.1) | 0.315 |

| Total time awake (mins) | 23 (21.3) | 24 (21) | −2.5 (−12.1, 17.1) | 0.719 |

| Overall sleepiness (1-Awake, 7-Not Awake) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.2) | −0.1 (−0.8, 1) | 0.826 |

| Quality of sleep (1-Bad, 4-Excellent) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.6) | −0.3 (−0.8, 0.2) | 0.230 |

Diff, differences in the mean of the groups.

Oral dexmedetomidine did not improve overnight motor sequence task performance

The number of correct MST responses after dexmedetomidine sleep remained stable from a mean of 26.8 (STD ±: 4.3) responses at training to a mean of 26.7 (6.1) correct responses at testing (Figure 1B). This mean difference of −0.1 [−2, 1.8] correct responses represented a 0.8% decrease in performance that did not meet our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.900). In contrast, overnight test performance after placebo sleep increased from a mean of 27.5 (6.2) correct responses at training to a mean of 29.8 (7.4) correct responses at testing (Figure 1B). This mean difference 2.3 [0.9, 3.7] represented a 7.9% increase in performance that met our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.003). These data are illustrated in figure 1B.

We found that oral dexmedetomidine was associated with a reduction in overnight MST performance of 9.3 [−1.4, 19.9] percent compared to placebo (Figure 1C). However, this group level difference did not meet our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.078).

Non-rapid eye movement sleep stage 2 spindle density and motor sequence task performance

In exploratory analyses, spindle density during non-REM stage 2 sleep and overnight MST improvement (Figure 1D) after oral dexmedetomidine were not correlated (Spearman’s Rho= 0.1, p = 0.748, n = 13; Spearman’s Rho= 0.1, p = 0.820, n = 15 after data imputation). Similarly, total spindle count during non-REM stage 2 sleep and overnight MST improvement after oral dexmedetomidine were not correlated (Spearman’s Rho= 0.04, p = 0.887, n = 13; Spearman’s Rho= 0.04, p = 0.899, n = 15 after data imputation). We confirmed the previously described24,26 positive correlation between spindle density during non-REM stage 2 sleep and overnight MST improvement (Figure 1E) post placebo (Spearman’s Rho= 0.54, p = 0.058, n = 13; Spearman’s Rho= 0.57, p = 0.028, n = 15 after data imputation). We also found a positive correlation between the total spindle count during non-REM stage 2 sleep and overnight MST improvement post placebo (r = 0.51, p = 0.074, n = 13; Spearman’s Rho= 0.57, p = 0.0287, n = 15 after data imputation).

Psychomotor vigilance was preserved after dexmedetomidine-induced sleep

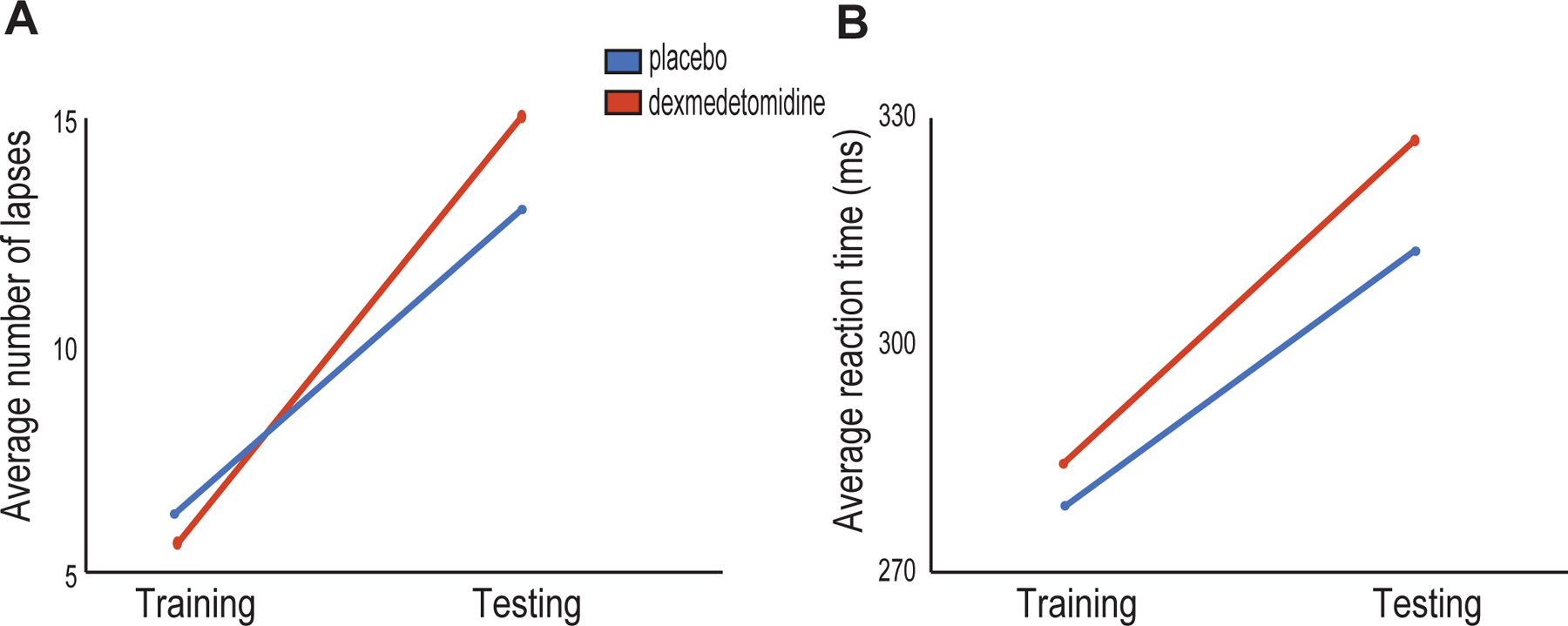

Lapse 400

We previously demonstrated that lapse 400 was impaired after zolpidem extended-release sleep.8 Lapse 400 after placebo sleep increased from a mean of 6.5 (7) lapses during the training performance to a mean of 12.3 (13.2) lapses during the testing performance (Figure 2A). This mean difference of 5.8 [0.5, 11.1] lapses met our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.036). Lapse 400 after dexmedetomidine-induced sleep increased from a mean of 5.8 (5) lapses during the training performance to a mean of 14.5 (15.5) lapses during the testing performance (Figure 2A). This mean difference of 8.6 [1.7, 15.7] lapses met our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.009).

Fig. 2.

PVT performance. (A) Testing lapse 400 during the placebo study visit was increased from training lapse 400 (p = 0.036). Testing lapse 400 during the dexmedetomidine study visit was also increased from training lapse 400 (p = 0.009). There was no statistically significant difference in testing lapse 400 between groups after controlling for training lapse 400 (p = 0.281). (B) The average testing reaction time during the placebo study visit was increased from the average training reaction times (p = 0.012). The average testing reaction time during the dexmedetomidine study visit was also increased from the average training reaction time (p = 0.014). There was no statistically significant difference between the average testing reaction times between groups after controlling for the average training reaction times (p = 0.295).

To make inferences on group differences, we analyzed AM-PM change scores using an appropriate statistical approach for our crossover design. The mean difference of 2.4 [−3.9, 8.7] in the AM-PM change scores at the group level did not meet our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.398).

Reaction Time

Reaction time after placebo sleep increased from a mean of 281.3 (36.5) milliseconds during training to a mean of 306.5 (53.8) milliseconds during testing (Figure 2B). This mean difference of 25.1 [6.3, 43.9] milliseconds met our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.012). Reaction time after dexmedetomidine-induced sleep increased from a mean of 284.7 (35.5) milliseconds during training to a mean of 319.9 (70) milliseconds during testing (Figure 2B). This mean difference of 35.2 [8.5, 62] milliseconds met our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.014).

To make inferences on group differences, we analyzed AM-PM change scores using an appropriate statistical approach for our crossover design. The mean difference of 7.1 [−15.2, 29.3] in the AM-PM change scores at the group level did not meet our threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.501).

No serious adverse events were reported during this study.

Discussion

In this investigation, we studied the effect of a capsule-based solid oral dosage formulation of dexmedetomidine on objective and subjective measures of sleep quality. Our major finding was that oral dexmedetomidine increased the duration of non-REM stage 2 sleep and decreased the duration of REM sleep. Non-REM stage 2 sleep spindle density and total spindle count have previously been positively correlated with overnight MST improvement.23,24,26 We confirmed these previously reported positive correlations with data from the placebo study arm. However, we did not find a positive correlation between oral dexmedetomidine-induced non-REM stage 2 spindle density or total spindle count and overnight MST performance. Differences in MST findings may have been secondary to impaired sleep dependent memory or slower than usual reaction times (i.e., residual drug effect on psychomotor function). Because our PVT measures of psychomotor function did not significantly differ between groups, we conjecture that oral dexmedetomidine impaired sleep dependent memory consolidation.

Our finding that dexmedetomidine promoted non-REM 2 sleep and preserved sleep cycling is consistent with laboratory1–5 and human studies8–11,13,27–30 that suggest dexmedetomidine modulates non-REM sleep circuitry. Sleep spindles, along with K-complexes, are a neurophysiological feature of non-REM stage 2 sleep.11,20 Sleep spindles are transient time-domain (~0.5 to 2 seconds) oscillations that are generated in the thalamus.20,31 They require intact thalamocortical and corticothalamic circuits for synchronization and propagation to cortical regions,20,32 and may act to prime neural networks for synaptic plastic processes by inducing calcium influx.33 Sleep spindles have been suggested to mediate the overnight consolidation of declarative and procedural memory.34–37 Sleep spindles are also associated with learning potential and intelligence,38,39 and sleep spindle abnormalities have been identified in several neurocognitive disorders affecting cognition.40,41,26 However, the mere manifestation of sleep spindles may not be sufficient for improvement in overnight MST performance.

The lack of a positive correlation between oral dexmedetomidine spindle density or total spindle count with overnight MST performance suggests that oral dexmedetomidine may have impaired the slow oscillation-spindle-ripple cross-frequency coupling dynamic that is important for sleep-dependent motor memory consolidation. The-two stage memory model assumes that new memories are transiently encoded to temporary storage represented by the hippocampus and surrounding structures before being transferred to long-term storage represented by the cortex.24,33 Transfer of memory from temporary to long-term storage is postulated to occur during non-REM sleep.24,33 This process is dependent on cross-frequency coupling between thalamocortical spindles and hippocampal sharp-wave ripples (i.e., sharp-wave ripples are nested on the trough of thalamocortical spindles).24,33,42 Spindle-ripple cross-frequency coupling is regulated by the ON and OFF phases of cortical slow oscillations.24,33,42 Thus the cortical slow oscillation regulates the hippocampal to cortical redistribution of memory.33,42 The lack of a positive correlation between oral dexmedetomidine spindle density or total spindle count with overnight MST performance suggests that oral dexmedetomidine may have impaired the slow oscillation-spindle-ripple cross-frequency coupling dynamic that is important for sleep-dependent motor memory consolidation.

The clinical implication of our finding is that oral dexmedetomidine may be further investigated and developed as a non-REM sleep-promoting sedative medication. However, whether the mortality,43 cognitive,43 and delirium sparing benefits14–18 of intravenous dexmedetomidine will be realized with a solid oral dosage formulation is unclear. The inhaled and intravenous anesthetic drugs in common clinical use significantly affect brain neurophysiology9,44–46 to likely explain why sleep disturbance is a hallmark of the postoperative period. Thus, future investigations are necessary to make clear the putative benefits of oral dexmedetomidine in the postoperative period, critical illness, and patients with primary and secondary sleep disorders. Limitations of our study include the small sample size, healthy study population, and administration of a single dose of oral dexmedetomidine. Thus, future larger studies are necessary to enable insights, in various study populations, on the effect of repeated drug administration. These studies may also enable insights into whether oral dexmedetomidine has longer term effects on sleep architecture (i.e., rebound REM sleep), and whether these effects are clinically relevant.

Our results demonstrate the feasibility of developing oral solid dosage formulations of dexmedetomidine as non-rapid eye movement sleep-promoting sedative medications. Refinements to drug formulation and dosing may enable more precise sleep stage targeting.

Acknowledgments:

Lorenzo Berra, M.D., Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A, served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Amaka Eneanya, M.D., M.P.H., Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A, served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Oleg Evgenov, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Care, and Pain Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York, U.S.A, served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

James Rhee, M.D., Ph.D., Instructor, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A, served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Kenneth Shelton, M.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A, served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Funding Statement: NIH NIA RO1AG053582 to OA; and, Innovation funds from the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital to OA. Funds from División de Anestesiología, Escuela de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile to JP.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Number: NCT02818569

Conflicts of Interest: OA has received speaker’s honoraria from Masimo Corporation and is listed as an inventor on pending patents on EEG monitoring and oral dexmedetomidine that are assigned to Massachusetts General Hospital. All other authors declare that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Correa-Sales C, Rabin BC, Maze M: A hypnotic response to dexmedetomidine, an alpha 2 agonist, is mediated in the locus coeruleus in rats. Anesthesiology 1992; 76: 948–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Nelson LE, Franks N, Maze M, Chamberlin NL, Saper CB: Role of endogenous sleep-wake and analgesic systems in anesthesia. J Comp Neurol 2008; 508: 648–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizobe T, Maghsoudi K, Sitwala K, Tianzhi G, Ou J, Maze M: Antisense technology reveals the alpha2A adrenoceptor to be the subtype mediating the hypnotic response to the highly selective agonist, dexmedetomidine, in the locus coeruleus of the rat. J Clin Invest 1996; 98: 1076–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nacif-Coelho C, Correa-Sales C, Chang LL, Maze M: Perturbation of ion channel conductance alters the hypnotic response to the alpha 2-adrenergic agonist dexmedetomidine in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Anesthesiology 1994; 81: 1527–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson LE, Lu J, Guo T, Saper CB, Franks NP, Maze M: The alpha2-adrenoceptor agonist dexmedetomidine converges on an endogenous sleep-promoting pathway to exert its sedative effects. Anesthesiology 2003; 98: 428–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akeju O, Brown EN: Neural oscillations demonstrate that general anesthesia and sedative states are neurophysiologically distinct from sleep. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2017; 44: 178–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Ferretti V, Guntan I, Moro A, Steinberg EA, Ye Z, Zecharia AY, Yu X, Vyssotski AL, Brickley SG, Yustos R, Pillidge ZE, Harding EC, Wisden W, Franks NP: Neuronal ensembles sufficient for recovery sleep and the sedative actions of alpha2 adrenergic agonists. Nat Neurosci 2015; 18: 553–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akeju O, Hobbs LE, Gao L, Burns SM, Pavone KJ, Plummer GS, Walsh EC, Houle TT, Kim SE, Bianchi MT, Ellenbogen JM, Brown EN: Dexmedetomidine promotes biomimetic non-rapid eye movement stage 3 sleep in humans: A pilot study. Clin Neurophysiol 2017; 129: 69–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akeju O, Pavone KJ, Westover MB, Vazquez R, Prerau MJ, Harrell PG, Hartnack KE, Rhee J, Sampson AL, Habeeb K, Gao L, Pierce ET, Walsh JL, Brown EN, Purdon PL: A comparison of propofol- and dexmedetomidine-induced electroencephalogram dynamics using spectral and coherence analysis. Anesthesiology 2014; 121: 978–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huupponen E, Maksimow A, Lapinlampi P, Sarkela M, Saastamoinen A, Snapir A, Scheinin H, Scheinin M, Merilainen P, Himanen SL, Jaaskelainen S: Electroencephalogram spindle activity during dexmedetomidine sedation and physiological sleep. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008; 52: 289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashmi JA, Loggia ML, Khan S, Gao L, Kim J, Napadow V, Brown EN, Akeju O: Dexmedetomidine Disrupts the Local and Global Efficiencies of Large-scale Brain Networks. Anesthesiology 2017; 126: 419–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexopoulou C, Kondili E, Diamantaki E, Psarologakis C, Kokkini S, Bolaki M, Georgopoulos D: Effects of dexmedetomidine on sleep quality in critically ill patients: a pilot study. Anesthesiology 2014; 121: 801–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oto J, Yamamoto K, Koike S, Onodera M, Imanaka H, Nishimura M: Sleep quality of mechanically ventilated patients sedated with dexmedetomidine. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 1982–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riker RR, Shehabi Y, Bokesch PM, Ceraso D, Wisemandle W, Koura F, Whitten P, Margolis BD, Byrne DW, Ely EW, Rocha MG, Group SS: Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009; 301: 489–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, Maze M, Girard TD, Miller RR, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Jackson JC, Deppen SA, Stiles RA, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW: Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007; 298: 2644–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reade MC, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Bersten A, Cheung B, Davies A, Delaney A, Ghosh A, van Haren F, Harley N, Knight D, McGuiness S, Mulder J, O’Donoghue S, Simpson N, Young P, Dah LIAI, the A, New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials G: Effect of Dexmedetomidine Added to Standard Care on Ventilator-Free Time in Patients With Agitated Delirium: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016; 316: 773–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maldonado JR, Wysong A, van der Starre PJ, Block T, Miller C, Reitz BA: Dexmedetomidine and the reduction of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Psychosomatics 2009; 50: 206–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su X, Meng ZT, Wu XH, Cui F, Li HL, Wang DX, Zhu X, Zhu SN, Maze M, Ma D: Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 1893–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mountain BW, Smithson L, Cramolini M, Wyatt TH, Newman M: Dexmedetomidine as a pediatric anesthetic premedication to reduce anxiety and to deter emergence delirium. AANA J 2011; 79: 219–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT, Strecker RE, McCarley RW: Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 2012; 92: 1087–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patanaik A, Ong JL, Gooley JJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Chee MWL: An end-to-end framework for real-time automatic sleep stage classification. Sleep 2018; 41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prerau MJ, Brown RE, Bianchi MT, Ellenbogen JM, Purdon PL: Sleep Neurophysiological Dynamics Through the Lens of Multitaper Spectral Analysis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2017; 32: 60–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker MP, Brakefield T, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R: Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron 2002; 35: 205–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manoach DS, Stickgold R: Abnormal Sleep Spindles, Memory Consolidation, and Schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2019; 15: 451–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker MP, Brakefield T, Seidman J, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R: Sleep and the time course of motor skill learning. Learn Mem 2003; 10: 275–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wamsley EJ, Tucker MA, Shinn AK, Ono KE, McKinley SK, Ely AV, Goff DC, Stickgold R, Manoach DS: Reduced sleep spindles and spindle coherence in schizophrenia: mechanisms of impaired memory consolidation? Biol Psychiatry 2012; 71: 154–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akeju O, Loggia ML, Catana C, Pavone KJ, Vazquez R, Rhee J, Contreras Ramirez V, Chonde DB, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Arabasz G, Hsu S, Habeeb K, Hooker JM, Napadow V, Brown EN, Purdon PL: Disruption of thalamic functional connectivity is a neural correlate of dexmedetomidine-induced unconsciousness. Elife 2014; 3: e04499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song AH, Kucyi A, Napadow V, Brown EN, Loggia ML, Akeju O: Pharmacological Modulation of Noradrenergic Arousal Circuitry Disrupts Functional Connectivity of the Locus Ceruleus in Humans. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 6938–6945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu XH, Cui F, Zhang C, Meng ZT, Wang DX, Ma J, Wang GF, Zhu SN, Ma D: Low-dose Dexmedetomidine Improves Sleep Quality Pattern in Elderly Patients after Noncardiac Surgery in the Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2016; 125: 979–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akeju O, Kim SE, Vazquez R, Rhee J, Pavone KJ, Hobbs LE, Purdon PL, Brown EN: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Dexmedetomidine-Induced Electroencephalogram Oscillations. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0163431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuentealba P, Steriade M: The reticular nucleus revisited: intrinsic and network properties of a thalamic pacemaker. Prog Neurobiol 2005; 75: 125–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCormick DA, Bal T: Sleep and arousal: thalamocortical mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci 1997; 20: 185–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Born J, Wilhelm I: System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychol Res 2012; 76: 192–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clemens Z, Fabo D, Halasz P: Overnight verbal memory retention correlates with the number of sleep spindles. Neuroscience 2005; 132: 529–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clemens Z, Fabo D, Halasz P: Twenty-four hours retention of visuospatial memory correlates with the number of parietal sleep spindles. Neurosci Lett 2006; 403: 52–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schabus M, Gruber G, Parapatics S, Sauter C, Klosch G, Anderer P, Klimesch W, Saletu B, Zeitlhofer J: Sleep spindles and their significance for declarative memory consolidation. Sleep 2004; 27: 1479–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamminen J, Payne JD, Stickgold R, Wamsley EJ, Gaskell MG: Sleep spindle activity is associated with the integration of new memories and existing knowledge. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 14356–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fogel SM, Nader R, Cote KA, Smith CT: Sleep spindles and learning potential. Behav Neurosci 2007; 121: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schabus M, Hodlmoser K, Gruber G, Sauter C, Anderer P, Klosch G, Parapatics S, Saletu B, Klimesch W, Zeitlhofer J: Sleep spindle-related activity in the human EEG and its relation to general cognitive and learning abilities. Eur J Neurosci 2006; 23: 1738–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibagaki M, Kiyono S, Watanabe K: Spindle evolution in normal and mentally retarded children: a review. Sleep 1982; 5: 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Limoges E, Mottron L, Bolduc C, Berthiaume C, Godbout R: Atypical sleep architecture and the autism phenotype. Brain 2005; 128: 1049–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sirota A, Buzsaki G: Interaction between neocortical and hippocampal networks via slow oscillations. Thalamus Relat Syst 2005; 3: 245–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang DF, Su X, Meng ZT, Li HL, Wang DX, Xue-Ying L, Maze M, Ma D: Impact of Dexmedetomidine on Long-term Outcomes After Noncardiac Surgery in Elderly: 3-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg 2019; 270: 356–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavone KJ, Su L, Gao L, Eromo E, Vazquez R, Rhee J, Hobbs LE, Ibala R, Demircioglu G, Purdon PL, Brown EN, Akeju O: Lack of Responsiveness during the Onset and Offset of Sevoflurane Anesthesia Is Associated with Decreased Awake-Alpha Oscillation Power. Front Syst Neurosci 2017; 11: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akeju O, Hamilos AE, Song AH, Pavone KJ, Purdon PL, Brown EN: GABAA circuit mechanisms are associated with ether anesthesia-induced unconsciousness. Clin Neurophysiol 2016; 127: 2472–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavone KJ, Akeju O, Sampson AL, Ling K, Purdon PL, Brown EN: Nitrous oxide-induced slow and delta oscillations. Clin Neurophysiol 2016; 127: 556–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]