SUMMARY

Objective

To examine the frequency and characteristics of ictal central apnea (ICA) in a selective cohort of patients with mesial or neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) undergoing surface video electroencephalography (EEG) and multimodal recording of cardiorespiratory parameters.

Methods

We retrospectively screened 453 patients who underwent EEG in a single center including nasal airflow measurements, respiratory inductance plethysmography of thoraco–abdominal excursions, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, and electrocardiography. Patients with confirmed TLE subtype, either by MRI lesions limited to the temporal neocortex or mesial structures and concordant neurophysiologic data or patients who underwent invasive explorations were included.

Results

ICA frequency and characteristics were analyzed in 41 patients with 164 seizures that had multimodal respiratory monitoring. The total occurrence of ICA in all seizures in this cohort was 79.9%. No significant difference was seen between mesial and neocortical temporal lobe seizures (79.8% and 80.0%, respectively). ICA preceded EEG onset by 13 ± 11 seconds in 33.3% of seizures and was the first clinical sign by 18 ± 14 seconds in 48.7%. Longer ICA duration trended towards a more severe degree of hypoxemia.

Conclusions

In a selective cohort of TLE defined by MRI-lesion and/or intracranial recordings, the frequency of ICA was higher than previously reported in the literature. Multimodal respiratory monitoring has localizing value and is generally well tolerated. ICA preceded both EEG on scalp recordings as well as clinical seizure onset in a substantial number of patients. Respiratory monitoring and ICA detection is even more paramount during invasive monitoring to confirm that the recorded seizure onset is seen before the first clinical sign.

Keywords: apnea, breathing, ictal central apnea, seizure, temporal lobe epilepsy

1. Introduction

Ictal central apnea (ICA) has been recognized as the only and often first clinical sign in focal epilepsies.[1–3] Recognizing the first clinical symptom is paramount, particularly during invasive epilepsy evaluations for which capturing an EEG onset preceding or coinciding with clinical onset remains a cardinal rule of correctly localizing the ictal onset.

Ictal central apnea (ICA) has been reported in 36.5 – 44% of focal onset seizures.[1,2,4] On scalp video EEG and excluding the convulsive phase of a seizure, the frequency of ICA was found to be higher in temporal lobe (53.8 – 54.3%) as opposed to extratemporal lobe (13.8 – 23.1%) seizures.[1,2] ICA was not seen during non-convulsive seizures in patients with generalized epilepsy syndromes. These recent findings suggest that ICA may be a localizing sign of TLE.

Recent human brain mapping studies using electrical stimulation have provided robust evidence that mesial temporal lobe (MTL) structures (e.g., hippocampus, amygdala, and anteromesial fusiform and parahippocampal gyri) have the potential to suppress breathing and likely provide the symptomatogenic substrate for ICA.[5–8] Additionally, the onset of ictal apnea in intracranially monitored seizures was highly correlated with seizure spread to the amygdala.[9] In a small series, mesial temporal lobe seizures confirmed by invasive recordings (68.7%) showed a higher occurrence of ICA than patients with unspecified temporal lobe epilepsy (53%) suggesting that ICA may help to distinguish between mesial and neocortical temporal lobe subtypes.[3] However, the prevalence of ICA in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) subtypes has not been studied in detail.

In this study, we aim to further analyze the frequency and characteristics of ICA in patients with mesial versus neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy defined by MRI and/or intracranial confirmed seizure onset.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient selection

This was a single – center, retrospective study with data collected at an academic teaching hospital. All patients were prospectively consented for a video EEG repository to allow their video EEG and respiratory parameters data to be used and analyzed for research purposes. This study was carried out with the approval of the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

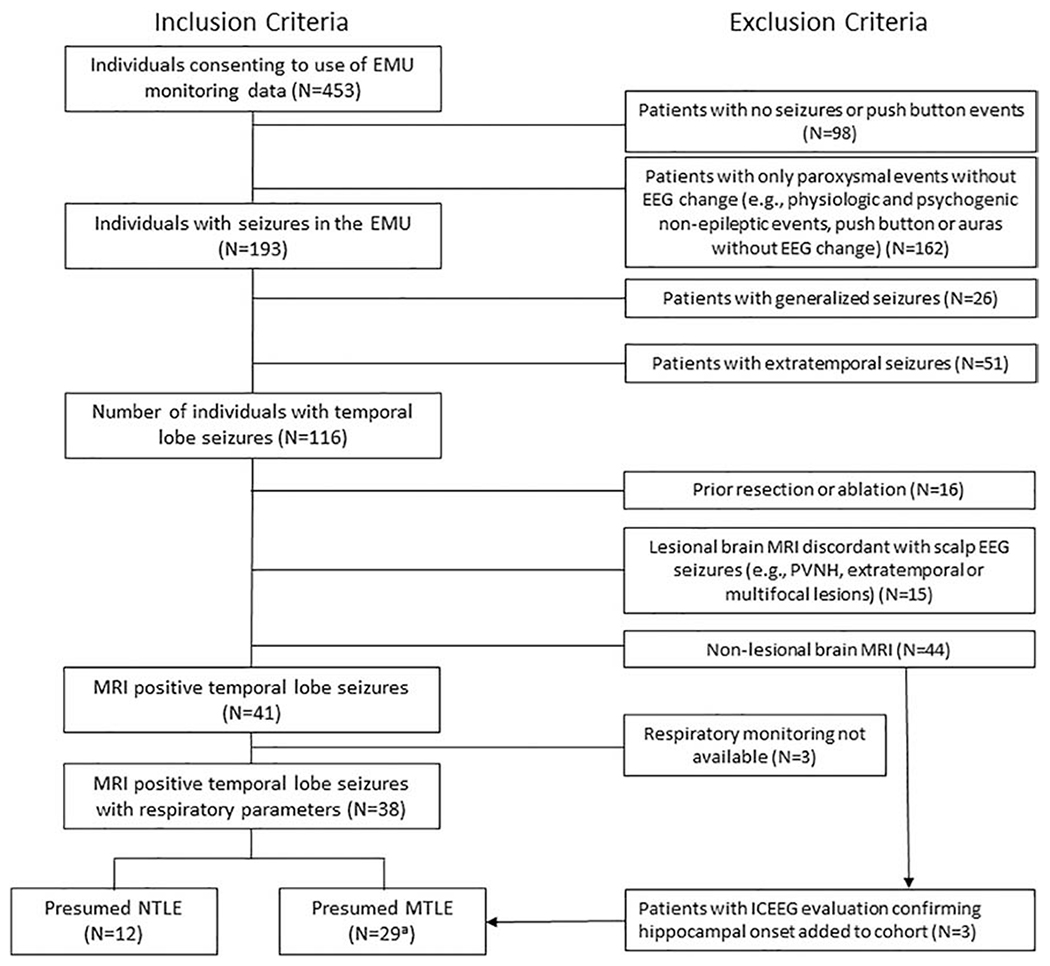

Patients were included in the data analysis through retrospective review of all patients admitted for surface EEG at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) from January 1, 2008 until December 31, 2018 (Figure 1). We included patients with suspected lesional temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and at least one recorded focal onset electrographic seizure with clinical correlate who had complete polygraphic physiological recordings sufficient for analysis. Data from surface EEG evaluations of patients with non – lesional (MRI – negative) TLE with a subsequent admission for invasive (e.g., stereotactic or subdural evaluation) EEG confirming either a neocortical or mesial temporal lobe seizure onset were included as well. Patients in this study were subdivided into presumed mesial and neocortical TLE based on lesion location and if available intracranial EEG.

Figure 1: Patient selection.

EMU: epilepsy monitoring unit; EEG: electroencephalogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PVNH: periventricular nodular heterotopias; MTLE: mesial temporal lobe epilepsy; NTLE: neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy; ICEEG: intracranial EEG

a The 29 presumed MTLE patients include 26 patients with a temporal lesion and concordant scalp EEG findings and 3 additional patients (MRI negative) that had invasive evaluation confirming a (mesial) temporal onset.

We excluded patients that did not have any EEG seizures recorded. We also excluded patients with presumed epileptic auras without EEG change. Patients with generalized, extratemporal, or multifocal epilepsies were excluded. Additionally, patients with an MRI showing a lesion discordant with EEG seizure onset, dual or multifocal pathology, or evidence of prior brain surgery (e.g., resection or laser ablation) were excluded.

2.2. Video EEG and cardiorespiratory monitoring

All patients had prolonged surface video EEG monitoring using the 10 – 20 International Electrode System, including T1 and T2 locations. EEG and electrocardiography (ECG) were acquired using the Nihon Kohden (Tokyo, Japan) acquisition platforms. Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) and heart rate were monitored using pulse oximetry (Masimo). As standard clinical protocol at NMH, respiratory monitoring is routinely conducted for all EMU patients. Patients were fitted with plethysmograph belts to measure chest and abdominal excursions (Dymedix Diagnostics). To measure airflow and respiratory effort through the nose, patients are also fitted with a disposable nasal thermistor and pressure transducer (Dymedix Diagnostics). In analyzing respiratory data for the purposes of our study, nasal respiratory data and respiratory belts were used in tandem, which has been shown to be more sensitive and accurate than belt data alone when measuring respiratory effort.[10]

2.3. Data collection

Two types of data were collected: 1) frequency of ICA in all recorded seizures in the EMU and 2) the relationship between ICA and clinical or electrographic ictal onset from the first recorded electroclinical seizure with reliable physiological recording.

Central apnea was defined as ≥1 missed breath without any other explanation (i.e., speech, movement, or intervention) lasting a minimal duration of five seconds.[2] ICA is referred to as apnea in non – convulsive seizures or in the pre – convulsive phase of a bilateral convulsive seizure. Breathing analysis for apnea utilized composite analysis of nasal airflow and thoraco – abdominal inductance plethysmography recordings and visually inspection of thoraco – abdominal excursions two minutes before seizure onset (clinical or electrographic, whichever occurred first).

Hypoxemia was defined as SpO2 < 95%. SpO2 baseline was determined two minutes pre – ictally as mean SpO2 during a 15 seconds, artifact free epoch. We used the lowest determination of SpO2 to evaluate nadir desaturation for ICA during non – convulsive seizures or the mean SpO2 in the 15 seconds epoch just before a tonic, clonic, or tonic – clonic convulsion.

Ictal tachycardia was defined as heart rate that exceeds 100 beats per minute.[11] Baseline heart rate was determined two minutes pre – ictally as mean heart rate in a 15 second, artifact free epoch. We used the peak heart rate during non – convulsive seizures or the mean heart rate in the 15 seconds epoch before a convulsive phase.

Video EEG recordings were re-analyzed and the electrographic, clinical and ICA onsets were determined by two clinical neurophysiologists (E.T. and G.C.). If there was any dispute regarding these onsets, the data was reviewed by a third clinical neurophysiologist (S.S). Clinical onset was defined as the time when the patient had an observable objective seizure semiology (e.g., automatisms, aphasia or unresponsiveness during clinical testing, focal or generalized tonic, clonic, versive, hypermotor or myoclonic movements, tachy- or bradyarrhythmias) or when the patient reported a subjective aura by pressing the bedside event button. The electrographic onset was established as the change in background interictal EEG when there was an appearance of rhythmic spiking, evolving theta, delta and/or alpha frequencies, and/or electrodecremental or low-voltage fast activity. The electrographic offset marked by the abrupt cessation of these pattern.

We excluded seizures from analysis that had significant EEG or respiratory channel artifact at or before seizure onset which prohibited data analysis. Auras without EEG changes or subsequent clinical signs were excluded from analysis.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Student’s t – test was used to estimate associations between continuous variables of equal variances, and Welch’s t –test was used to estimate associations between continuous variables of unequal variances. Chi square test was applied to assess associations between categorical variables, and Fisher’s exact test was used to estimate associations between categorical variables with expected frequencies of less than five. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 16 (College Station, TX).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and epilepsy characteristics

A total of 453 patients underwent polygraphic study of seizures in the EMU during the study period and consented to research use of their EMU data. Forty – one patients (26 female) met inclusion criteria for this study. A total of 194 seizures were recorded in the EMU. Mean age was 41.6 ± 11.9 years. Mean epilepsy duration was 18.2 ± 16.6 years (MTLE 22.1 ± 17.7; NTLE 8.7 ± 8.3; p=0.002). At the time of admission, patients were prescribed 2.6 ± 1.1 antiseizure drugs (range 0 – 5; MTLE 2.9 ± 1.0; NTLE 1.9 ± 0.9; p=0.007).

Twenty – nine patients had a presumed epileptogenic zone within the mesial temporal lobe, while 12 patients were classified as neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy. Twenty – two patients (53.7%) were identified by MRI lesion alone. Sixteen patients (39%) with an MRI lesion concordant with the scalp ictal onset zone underwent a subsequent phase II invasive evaluation confirming the intracranial seizure onset arising from the peri –lesional region. Three patients had a negative MRI, but on a subsequent invasive EEG were found to have mesial temporal seizure onset and data from the initial surface EEG evaluation were included (Table 1). Seizure lateralization was on the right in 20/41 patients (48.8%; MTLE 51.7%; NTLE 41.2%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Variable | Total (N=41) | MTLE (N=29) | NTLE (N=12) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.6 ± 11.9 | 42.5 ± 12.7 | 39.4 ± 10.3 | 0.42 |

| Sex (female) | 26 (63.4) | 19 (65.5) | 7 (58.3) | 0.73 |

| Epilepsy duration (years) | 18.2 ± 16.6 | 22.1 ± 17.7 | 8.7 ± 8.3 | 0.002 |

| Number of ASDs | 2.59 ± 1.05 | 2.86 ± 0.99 | 1.92 ± 0.90 | 0.007 |

| Localization | 0.58 | |||

| By lesion | 22 (53.7) | 16 (55.2) | 6 (50.0) | |

| By invasive recording | 3 (7.3) | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Both | 16 (39.0) | 10 (34.5) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Seizure lateralization (Right) | 20 (48.8) | 15 (51.7) | 5 (41.2) | 0.56 |

| Patients with at least one ICA | 39 (95.1) | 28 (96.6) | 11 (91.7) | 0.51 |

| Total # seizures recorded | 194 | 146 | 48 | -- |

| Total # seizures included | 164 | 119 | 45 | -- |

| Mean # seizures per patient | 4.00 ± 2.81 | 4.10 ± 3.04 | 3.75 ± 2.26 | 0.69 |

| Seizures with ICA | 131 (79.9) | 95 (79.8) | 36 (80.0) | 0.98 |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD, categorical variables as frequency (%).

MTLE – mesial temporal lobe epilepsy; NTLE – neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy; ASD – anti-seizure drugs; ICA – ictal central apnea

3.2. Ictal apnea and seizure characteristics

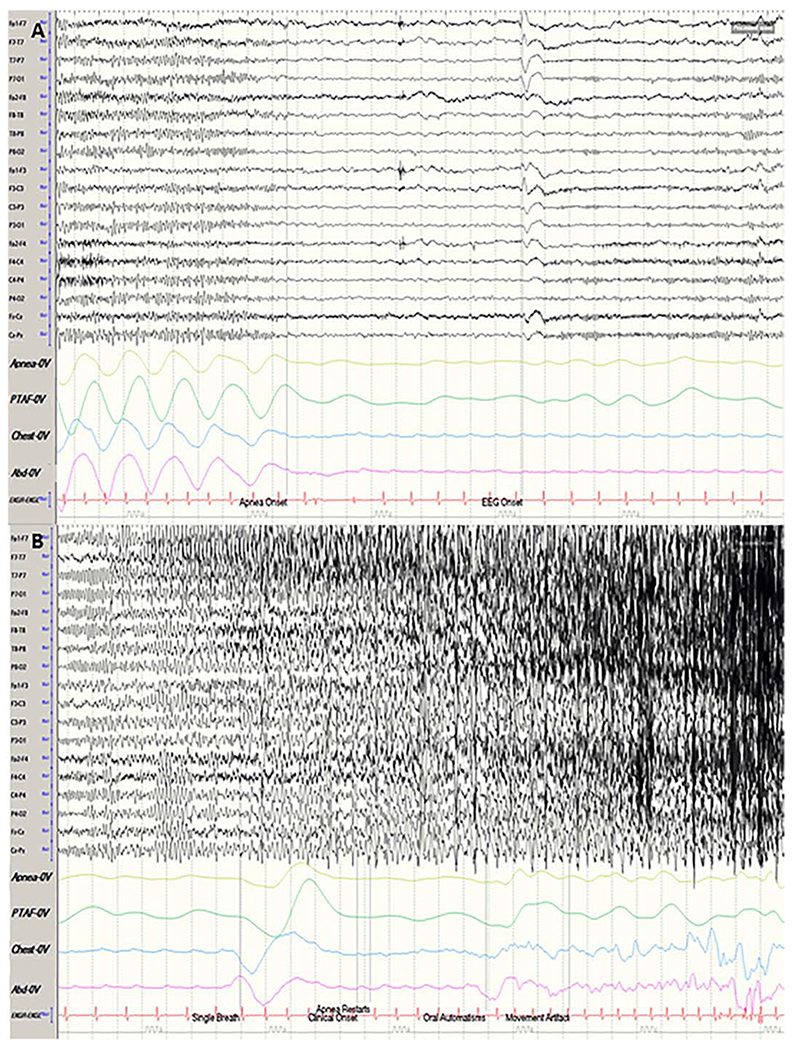

Of the 194 seizures recorded in the EMU, 164 had reliable respiratory recordings for assessment of breathing responses and were included for data analysis. The average number of included recorded seizures per patient was 4.0 ± 2.8 seizures (median 3; range 1-15). Figure 2 illustrates an example of a recorded ictal central apnea in a patient with multimodal respiratory and EEG recordings. In 30 seizures, respiratory parameters were not analyzable and excluded for the following reasons: insufficient multimodal respiratory recording quality (e.g., movement or dislodged sensors) (n=17), seizures recorded in the ictal SPECT lab which does not have respiratory recording capabilities (n=8), and typical auras without an EEG correlate (n=5). None of the auras without EEG correlate had an ICA.

Figure 2: Left temporal lobe seizure with an early ictal central apnea (ICA).

Sensitivity 7 uV; High frequency filter 70 Hz; Low frequency filter 1.6 Hz. A left temporal lobe seizure is shown in 2 consecutive 30 second pages with additional respiratory channels (Apnea and pressure transducer airflow (PTAF) channels measure nasal airflow via temperature and pressure, respectively, and chest/abd channels measure thoraco – abdominal respiratory excursions). In (A), the patient is in a drowsy state with eyes closed and has regular breathing in the first eight seconds of the page. An attenuation of the patient’s posterior dominant rhythm is seen at this time. Cessation of breathing movements are illustrated by flattening of both nasal and thoraco – abdominal plethysmographic tracings. ICA lasts 27 seconds before taking the next breath (B). ICA is recorded 10 seconds before the scalp EEG onset which was marked by a broad sharp wave, diffuse attenuation, and subsequent repetitive discharges seen over the left temporal lobe. ICA is seen 24 seconds before the first observable clinical sign on video: the patient opening his eyes, stares ahead before subsequently developing oral and then manual automatisms.

ICA was found in 131/164 (79.9%) seizures. ICA was seen in nearly the same proportion of mesial and neocortical temporal lobe seizures: 95/119 (79.8%) versus 36/45 (80.0%), respectively. In 15 otherwise purely electrographic seizures, apnea was the sole clinical manifestations in two seizures (1 MTLE, 1 NTLE), comprising 1.2% (2/164) of all seizures recorded. Among the 41 patients included, 39 patients (95.1%) had at least one seizure recorded with an ICA. One patient with NTLE and one with MTLE did not have an ICA recorded with any seizure.

In the first seizures of the 39 patients with ictal apnea, mean ICA duration was 16 ± 17 seconds. Apnea duration was 14 ± 10 seconds in MTL onset seizures and 21 ± 28 seconds in NTL onset seizures (p=0.47). In 16 out of the 39 seizures (41%), apnea offset time (after a minimum five seconds) was determined prematurely due an increase in artifact from movement, talking, or onset of tonic, clonic or tonic – clonic phase of the seizure which contaminated the true apnea offset. It should be noted that one patient in the NTLE group had an prolonged ICA lasting 101 seconds and a subsequent oxygen saturation nadir of 51% which greatly increased the standard deviation for the ICA duration for the total and NTLE group.

Mean EEG and clinical seizure duration was 98 ± 74 seconds and 95 ± 70 seconds, respectively. Neocortical onset seizures tended to be shorter (mean clinical seizure length 79 ± 38 seconds; mean EEG seizure 86 ± 46 seconds) compared to mesial onset seizures (mean clinical seizure length 101 ± 79 seconds; mean EEG seizure 102 ± 83 seconds), but no statistical difference was found (p=0.27 and 0.43, for clinical and EEG duration respectively).

The most common seizure semiology in the 41 first recorded seizures was focal onset impaired awareness (FOIA) (n=33): 16 were FOIA seizures with automatisms, 16 were FOIA non – motor seizures (n=16), and one had FOIA with hyperkinetic movements. Focal aware seizures occurred in 5 patients. In three patients, we could not determine whether the patient was aware or not as they occurred out of sleep and were not clinically tested. In 16 seizures, patients reported a subjective aura prior to the first objective sign (13/28 (44.8%) MTLE, 3/11 (25%) NTLE, p=0.31). Twelve seizures progressed from focal to bilateral tonic – clonic seizures.

3.3. Ictal apnea relationship with EEG onset/clinical onset

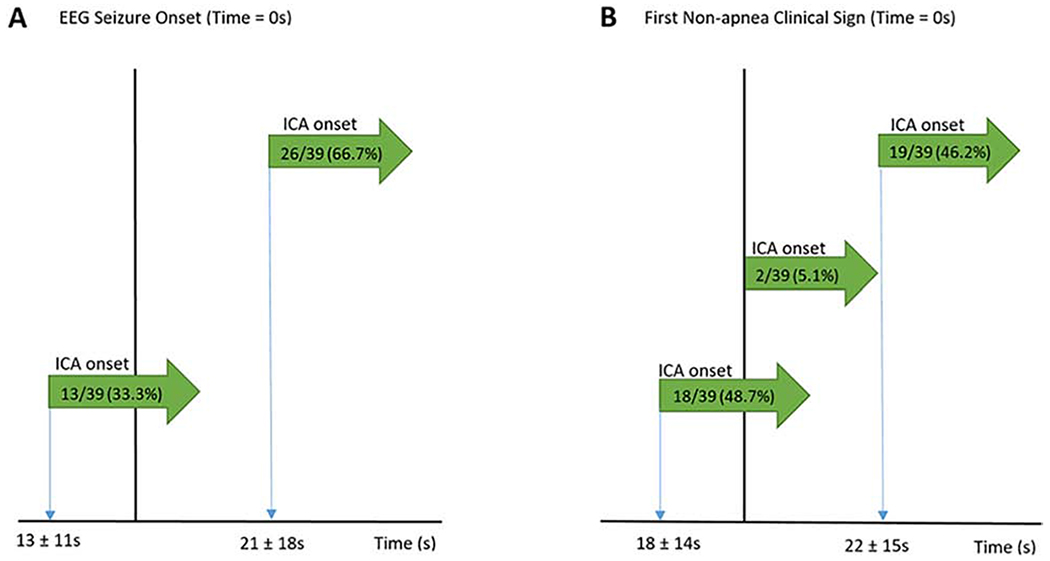

In the first seizure containing an ICA in each patient, ICA preceded the EEG seizure onset in 13/39 events (33.3%; MTL onset 28.5%, NTL onset 46.0%) by 13 ± 11 seconds (Figure 3). On the contrary, ICA occurred after surface EEG seizure onset in 26/39 events (66.7%; MTL onset 71.4%, NTL onset 54.5%) delayed by 21 ± 18 seconds. ICA and EEG onset did not coincide in any seizures (defined as ≤ 1 second difference).

Figure 3: Ictal central apnea (ICA) timing with respect to EEG onset (A) and clinical onset (B).

In (A) and (B), the green arrow represents the onset of ICA relative to the EEG seizure onset and clinical seizure onset, respectively. Duration of onset of ICA before or after EEG/clinical onset is reported as mean ± standard deviation.

ICA was the first clinical sign in 19/39 seizures (48.7%; MTL onset 46.4%, NTL onset 54.5%) by 18 ± 14 seconds. ICA was a later clinical sign in 18/39 seizures (46.2%; MTL onset 50.0%, NTL onset 36.4%) by 22 ± 15 seconds. ICA coincided with the first non-apnea clinical onset (≤ 1 second difference) in two seizures (5.1%). Differences between MTL and NTL onset seizures were not significant.

3.4. Apnea relationship with oxygen saturation and tachycardia

Ictal hypoxemia (SpO2 < 95%) was present in 17/38 (44.7%) of seizures and was unable to be recorded in one patient. Desaturation was seen below 90% in 7/17 (41.2%) of seizures and below 80% in one seizure (Table 2). Mean oxygen desaturation nadir was 93.5 ± 8.3% (MTL onset 94.8 ± 4.5%; NTL onset 90.2 ± 13.7%; p=0.30). Duration of ICA trended towards a negative correlation with SpO2 nadir, however, this did not reach significance (r = −0.28; p < 0.086). Ictal tachycardia was seen in 29/39 patients (76.3%; MTL onset 77.8%, NTL onset 72.7%, p=0.74) and mean maximum heart rate during the non – convulsive seizure phase was 116.1 ± 27.5 beats per minute (MTL onset 116.5 ± 27.7, NTL onset 115 ± 28.3, p=0.88).

Table 2.

Seizure and Apnea Characteristics

| Variable | Total (N=39) | MTLE (N=28) | NTLE (N=11) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical seizure duration | 0:01:35 ± 0:01:10 | 0:01:41 ± 0:01:19 | 0:01:19 ± 0:00:38 | 0.27 |

| EEG seizure duration | 0:01:38 ± 0:01:14 | 0:01:42 ± 0:01:23 | 0:01:26 ± 0:00:46 | 0.44 |

| FBCS | 12 (29.3) | 9 (31.0) | 3 (25.0) | 0.70 |

| Position during apnea | 0.39 | |||

| Supine | 15 (38.5) | 12 (42.8) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Sitting | 13 (33.3) | 7 (25.0) | 6 (54.5) | |

| Lateral | 10 (25.6) | 8 (28.6) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Unknown (covered) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Apnea durationa | 0:00:16 ± 0:00:17 | 0:00:14 ± 0:00:10 | 0:00:21 ± 0:00:28 | 0.47 |

| Desaturation (%) | 17 (44.7) | 11 (40.7) | 6 (54.5) | 0.49 |

| Nadir SpO2 (mean %) | 93.5 ± 8.3 | 94.8 ± 4.5 | 90.2 ± 13.7 | 0.30 |

| Tachycardia (%) | 29 (76.3) | 21 (77.8) | 8 (72.7) | 0.74 |

| Tachycardia (Max HR) | 116.1 ± 27.5 | 116.5 ± 27.7 | 115 ± 28.3 | 0.88 |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD, categorical variables as frequency (%).

MTLE – mesial temporal lobe epilepsy; NTLE – neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy; EEG – electroencephalography; FBCS – focal to bilateral convulsive seizure; SpO2 – blood oxygen saturation; HR – heart rate

Apnea offset determined by when the patient resumed breathing, waveforms became obscured by artifact due to movement or progression of seizure to convulsive phase of seizure

4. Discussion

ICA is a frequent, self – limiting semiological feature of TLE, often starting before surface EEG onset, and in almost half the patient presenting as the first clinical sign of the seizure. Prolonged ICA is associated with severe hypoxemia and may be a potential SUDEP biomarker.[1,2,12] ICA is not generally used as a semiological sign in the diagnostic or pre – surgical evaluation of patients with focal epilepsy. This is because respiratory function has not been routinely assessed during epilepsy monitoring in the past. The occurrence of ICA in focal seizures and the role of mesial temporal structures in the generation of ICA have only recently been described in the literature. The presence of ICA remains elusive to the examiner without multimodal respiratory monitoring as it may be the sole clinical manifestation of a seizure, and patients are agnostic to these symptoms.[1,2,5]

Previous studies of surface video EEG with large numbers of patients have characterized ICA incidence in a heterogeneous population, including focal and generalized onset seizure types with subgroup analysis of lobar onset and lateralization.[1,2,4] In these studies, ICA appears to be exclusive to focal epilepsies, and more frequently seen in temporal than extratemporal seizures. However, a limitation of studies evaluating ICA is the inability to reliably measure central apnea during the convulsive phase of a seizure, which was therefore excluded. Nevertheless, electrical stimulation studies in patients undergoing intracranial EEG have shown that stimulation of mesial temporal lobe structures (hippocampus, amygdala, and anteromesial fusiform and parahippocampal gyri) induces central apnea in the absence of afterdischarges.[5–8] Furthermore, in a study of patients monitored with invasive EEG, the onset of ictal apnea was highly correlated with seizure spread to the amygdala compared to the hippocampus in 22 seizures.[9] In another study of patients undergoing invasive epilepsy surgery evaluations for intractable MTLE, the ICA incidence in mesial temporal lobe seizures was 68.7% and was often the first clinical sign.[3]

In this study, we intended to further investigate the frequency and characteristics of ICA in patients with confirmed mesial and neocortical temporal epilepsy subtypes undergoing surface EEG recording. Ictal apnea characteristics in our cohort were consistent with known literature that ICA is an important semiological sign of temporal lobe onset seizures. Our incidence of ICA (79.9%) in this cohort was higher than those previously reported. This incidence was also higher than invasively recorded MTL seizures (68.7%).[3] There are a couple of likely possible explanations. We excluded patients in the EMU in which we only recorded aura without surface EEG change. In addition, we used a minimum cutoff of five seconds for ICA as defined by Vilella et al., 2019 compared to six seconds in one prior study.[3] EEG seizure characteristics and ICA duration were consistent with previous reports. ICA preceded the EEG seizure in 33% and was the first clinical sign in 49% of seizures. In prior studies, ICA preceded EEG seizure onset in 47 – 54%, and ICA was the first clinical sign in 61 – 69%.[1,2] These differences may be in part be due to the varying existing definitions of ictal central apnea and examiner differences in regards to interpretation of plethysmography tracings and EEG characteristics.

A secondary objective was to characterize differences between neocortical and mesial temporal lobe seizures in our cohort. No significant difference was seen in the ICA frequency, duration, or correlation with EEG/clinical onset between NTL and MTL seizures. There was a trend for longer ICA duration and degree of hypoxemia in patients with NTL versus MTL onset seizures despite the converse trend for NTL clinical and EEG seizures to be shorter than MTL seizures. These findings are limited by a small sample size and in part due to the insensitive nature of surface EEG to distinguish the true timing of seizure onset and propagation within structures within the temporal lobe associated with ICA.

Our and prior studies show that presence of ICA is frequent, occurs early in the seizure, and often occurs before the EEG onset and/or may be the first clinical sign. However, this study also demonstrated that ICA does not appear to distinguish between MTLE and NTLE seizures that are recorded on surface video EEG. Our findings support that ICA may provide the same, if not better, anatomo – electro – clinical localization of a autonomic clinical seizure onset than ictal tachycardia which has been well described in the literature. Published literature vary in the localizing value of ictal tachycardia. In two studies, 62 – 78% of seizures of temporal lobe onset associated with changes in heart rate compared to 11 – 22% in extratemporal seizures.[13,14] However, no difference in heart rate changes in temporal and extratemporal seizures[15] and temporal and frontal lobe seizures have also been reported.[16] Contradicting findings exist when considering heart rate change and EEG onset in mesial vs. neocortical temporal lobe seizures.[16,17] Taken together, ICA may be a more useful semiologic sign than ictal tachycardia since the onset can be seen as an abrupt cessation of nasal airflow and thoraco-abdominal breathing compared to changes in electrocardiogram, which can be gradual and more difficult to correlate with EEG onset. Analysis of ICA is not without limitations; it is often difficult to identify true breathing movements from artifact and there is not a consensus on the minimal duration of breathing cessation required to define an ICA.

Our study is consistent with prior reported literature of a trend for negative correlation between ICA duration and degree of hypoxemia. Although a correlation between the presence of ICA and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) has not been discovered, prolonged ICA (>60 second), which is associated with severe hypoxemia, is postulated to be a possible biomarker for SUDEP, and has been reported in single cases of patients that subsequently had SUDEP or near – SUDEP.[1,2,12] Additionally, the entity of post – convulsive central apnea (PCCA), which is likely due to different pathophysiology than ICA and not analyzed in this study, is emerging as a possible biomarker for SUDEP.[18] These findings argue for the use of multimodal respiratory recordings in the EMU setting to become more routine for risk – stratification and surgical localization. A recent study of 100 EMU subjects reporting their experience with a monitoring protocol that included the continuous measurements of oral/nasal airflow, respiratory effort (chest and abdominal respiratory inductance plethysmography), oxygen saturation, and transcutaneous CO2 demonstrated patient acceptance of a comprehensive cardiorespiratory monitoring protocol and a high tolerability.[19]

Limitations of our study are the observational and retrospective nature of a study in a fairly small group of patients. Due to strict inclusion criteria at the onset of the study, only 41 out of 453 patients (9.1%) were analyzed. Our results may be difficult to generalize over the broader population of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, including those that are non-lesional or have purely auras as their semiology. Breathing analysis through polygraphic recordings was limited to examining thoraco – abdominal movements on video and plethysmography recording and measurement of nasal airflow which is often subjected to multiple types of artifact, from movement, talking, or eating, which may prevent the detection of ICA and underestimate the incidence. Conversely, our apnea definition of five seconds may overestimate the incidence of ICA. Our definition was similar to that used in a recent study[2], however was shorter in duration than two other studies.[1,3] Despite the use of airflow and thoraco – abdominal monitoring, it should be noted that absolute distinction between obstructive and nonobstructive apnea can only be made with direct measurement of chest wall/diaphragm EMG or measures of esophageal pressure.[20] It may be beneficial in the future to develop a standardized definition of ICA and protocols for monitoring respiration in the EMU.

5. Conclusion

ICA is recognized as an important semiological sign in the localization of temporal lobe seizures. It appears paramount to identify ICA during invasive monitoring to confirm that the recorded seizure onset precedes onset of the apnea as the first clinical sign. Patients with TLE have a high frequency of ICA likely related to involvement of mesial temporal structures, in particular the amygdala, in respiratory control.

ICA characteristics in our cohort showed an even higher prevalence in TLE than previously published. ICA was the first clinical sign in 48.7% of our patients. Patients are typically agnostic of the apnea and self – reporting is unreliable. Systematic monitoring with multimodal respiratory monitoring using impedance plethysmography and nasal airflow parameters is highly recommended. ICA and PCCA are emerging as possible biomarkers for SUDEP, although larger prospective studies are still needed to validate this observation.

Highlights.

Ictal central apnea (ICA) is seen in 80% of temporal lobe seizures on scalp EEG

The frequency of ICA was similar in mesial and neocortical temporal seizures

ICA preceded the EEG seizure onset in 33% of recorded seizures

ICA was the first clinical sign in 49% of recorded seizures

Acknowledgments

Disclosures of conflict of interests and funding

Dr. Schuele’s work was funded by the NINDS RFA-NS-14-004 and the NIDCD R01-DC016364. He receives honoraria from Eisai, Inc., Greenwich, SK Life Science, Neurelis and Sunovion Ltd. for speaker bureau activities. Elizabeth Bachman and Drs. Tio and Culler report no relevant disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Lacuey N, Zonjy B, Hampson JP, Rani MRS, Zaremba A, Sainju RK, et al. The incidence and significance of periictal apnea in epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 2018;59:573–82. 10.1111/epi.14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vilella L, Lacuey N, Hampson JP, Rani MRS, Loparo K, Sainju RK, et al. Incidence, Recurrence, and Risk Factors for Peri-ictal Central Apnea and Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy. Front Neurol 2019;10:1–13. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lacuey N, Hupp NJ, Hampson J, Lhatoo S. Ictal Central Apnea (ICA) may be a useful semiological sign in invasive epilepsy surgery evaluations. Epilepsy Res 2019;156:106164 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.106164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bateman LM, Li CS, Seyal M. Ictal hypoxemia in localization-related epilepsy: Analysis of incidence, severity and risk factors. Brain 2008;131:3239–45. 10.1093/brain/awn277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dlouhy BJ, Gehlbach BK, Kreple CJ, Kawasaki H, Oya H, Buzza C, et al. Breathing inhibited when seizures spread to the amygdala and upon amygdala stimulation. J Neurosci 2015;35:10281–9. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0888-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lacuey N, Zonjy B, Londono L, Lhatoo SD. Amygdala and hippocampus are symptomatogenic zones for central apneic seizures. Neurology 2017;88:701–5. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lacuey N, Hampson JP, Harper RM, Miller JP, Lhatoo S. Limbic and paralimbic structures driving ictal central apnea. Neurology 2019;92:E655–69. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nobis WP, Schuele S, Templer JW, Zhou G, Lane G, Rosenow JM, et al. Amygdala-stimulation-induced apnea is attention and nasal-breathing dependent. Ann Neurol 2018;83:460–71. 10.1002/ana.25178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nobis WP, González Otárula KA, Templer JW, Gerard EE, VanHaerents S, Lane G, et al. The effect of seizure spread to the amygdala on respiration and onset of ictal central apnea. J Neurosurg 2019:1–11. 10.3171/2019.1.JNS183157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Johnson BN, Russell C, Khan RM, Sobel N. A comparison of methods for sniff measurement concurrent with olfactory tasks in humans. Chem Senses 2006;31:795–806. 10.1093/chemse/bjl021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Eggleston KS, Olin BD, Fisher RS. Ictal tachycardia: The head-heart connection. Seizure 2014;23:496–505. 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schuele SU, Afshari M, Afshari ZS, Macken MP, Asconape J, Wolfe L, et al. Ictal central apnea as a predictor for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2011;22:401–3. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Garcia M, D’Giano C, Estellés S, Leiguarda R, Rabinowicz A. Ictal tachycardia: Its discriminating potential between temporal and extratemporal seizure foci. Seizure 2001;10:415–9. 10.1053/seiz.2000.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Weil S, Arnold S, Eisensehr I, Noachtar S. Heart rate increase in otherwise subclinical seizures is different in temporal versus extratemporal seizure onset: Support for temporal lobe autonomic influence. Epileptic Disord 2005;7:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Işík U, Ayabakan C, Tokel K, Özek MM. Ictal electrocardiographic changes in children presenting with seizures. Pediatr Int 2012;54:27–31. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schernthaner C, Lindinger G, Pötzelberger K, Zeiler K, Baumgartner C. Autonomic epilepsy—the influence of epileptic discharges on heart rate and rhythm. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1999;111:392–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Di Gennaro G, Quarato PP, Sebastiano F, Esposito V, Onorati P, Grammaldo LG, et al. Ictal heart rate increase precedes EEG discharge in drug-resistant mesial temporal lobe seizures. Clin Neurophysiol 2004;115:1169–77. 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vilella L, Lacuey N, Hampson JP, Rani MRS, Sainju RK, Friedman D, et al. Postconvulsive central apnea as a biomarker for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Neurology 2019;92:E171–82. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gehlbach BK, Sainju RK, Tadlock DK, Dragon DN, Granner MA, Richerson GB. Tolerability of a comprehensive cardiorespiratory monitoring protocol in an epilepsy monitoring unit. Epilepsy Behav 2018;85:173–6. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:597–619. 10.5664/jcsm.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]