Abstract

Background:

Predischarge capillary blood gas partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) has been associated with increased adverse events including readmission. This study aimed to determine if predischarge pCO2 or 36-week pCO2 was associated with increased respiratory readmissions or other pulmonary healthcare utilization in the year after neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) discharge for infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) discharged with home oxygen, using a standardized outpatient oxygen weaning protocol.

Methods:

This was a secondary cohort analysis of infants born <32 weeks gestational age with BPD, referred to our clinic for home oxygen therapy from either from our level IV NICU or local level III NICUs between 2015 and 2017. Infants with major nonrespiratory comorbidities were excluded. Subject information was obtained from electronic health records.

Results:

Of 125 infants, 120 had complete 1-year follow-up. Twenty-three percent of infants experienced a respiratory readmission after NICU discharge. There was no significant association between predischarge or 36-week pCO2 and respiratory readmissions, emergency room visits, new or increased bronchodilators, or diuretics. Higher 36-week pCO2 was associated with a later corrected age when oxygen was discontinued (<6 months; median, 54 mmHg; interquartile range [IQR], 51–61; 6–11 months; median, 62 mmHg; IQR, 57–65; ≥12 months, median, 66 mmHg; IQR, 58–73; p = .006).

Conclusions:

Neither predischarge pCO2 nor 36-week pCO2 was associated with 1-year respiratory readmissions. However higher pCO2 at 36 weeks was associated with a longer duration of home oxygen. Neonatal illness measures like 36-week pCO2 may be useful in communicating expectations for home oxygen therapy to families.

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, home oxygen therapy, pCO2

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is the most common comorbidity associated with very preterm birth; 10,000–15,000 infants annually have this condition.1,2 A newer classification system proposed by Jensen and colleagues groups infants based on support at 36 weeks postmenstrual age: no BPD, no support; Grade 1, nasal cannula ≤2 L/min; Grade 2, nasal cannula >2 L/min or noninvasive positive airway pressure; Grade 3, invasive mechanical ventilation.3 Infants with greater severity of BPD are at higher risk of health complications after Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) discharge.3,4 During the first year of life they are at increased risk of being readmitted to the hospital, and frequently receive home oxygen therapy and additional medications such as inhaled and systemic corticosteroids.5–9 For this reason, strategies to optimize safe NICU discharge for infants with BPD are an important focus of research.

A previous study found that infants discharged from the NICU with a predischarge blood gas partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) > 60 mmHg had a higher risk of postdischarge adverse outcomes including hospital readmission.4 Baseline hypercapnia may indicate reduced respiratory reserve, which may place infants at risk for postdischarge complications.4,10 For infants discharged with home oxygen therapy, who already have increased healthcare needs after discharge, the potential readmission risk associated with baseline hypercapnia may indicate an infant who is not ready for NICU discharge. Due to this, it is our hospital’s recommendation to discharge infants with BPD with home oxygen therapy only after they have a pCO2 ≤ 60 mmHg on capillary blood gas. However, there have been no prospective studies examining outcomes following the use of predischarge pCO2 as a clinical guideline.

The objective of this study was to determine whether, for infants with BPD discharged with home oxygen therapy, capillary blood gas pCO2 obtained before NICU discharge was correlated with increased respiratory readmissions or other pulmonary healthcare utilization in the year after NICU discharge. We hypothesized that higher pCO2 in these infants would be a surrogate marker for increased pulmonary fragility after NICU discharge, and therefore would be associated with more readmissions and other hospital encounters, more outpatient respiratory medical management, and longer duration of home oxygen therapy.

2 |. METHODS

This was an observational cohort study with two groups to the cohort. For the first “NICU group,” we included infants that were part of a larger prospective study of infants admitted to our single-center level IV NICU from 2015 to 2017. Eligible infants were born <32 weeks’ gestation, with BPD defined as respiratory support at 36 weeks postmenstrual age, and discharged with home oxygen.11,12 We excluded infants with major surgical nonrespiratory comorbidities and tracheostomies, and we included only one member of a multiple gestations. In our NICU, infants anticipating discharge with home oxygen receive a pediatric pulmonary consultation in the NICU, pass an overnight pulse oximetry test on the prescribed liter flow of oxygen, and generally have a capillary blood gas with a PCO2 ≤ 60 mmHg before discharge. Because of this clinical practice, we thought few infants in our center would have high predischarge pCO2s, so we also reviewed records from our pediatric pulmonary BPD clinic to include a “referral group” of infants discharged from other local level III NICUs and referred to our clinic for home oxygen management. Infants in the referral group had the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as the prospective study cohort but did not have the same centralized inpatient discharge practice guidelines. Caregivers were consented for the larger prospective observational cohort study in our NICU; the referral cohort was considered exempt as a retrospective chart review. Only records from our institution, either our NICU or outpatient clinic, were used for the study.

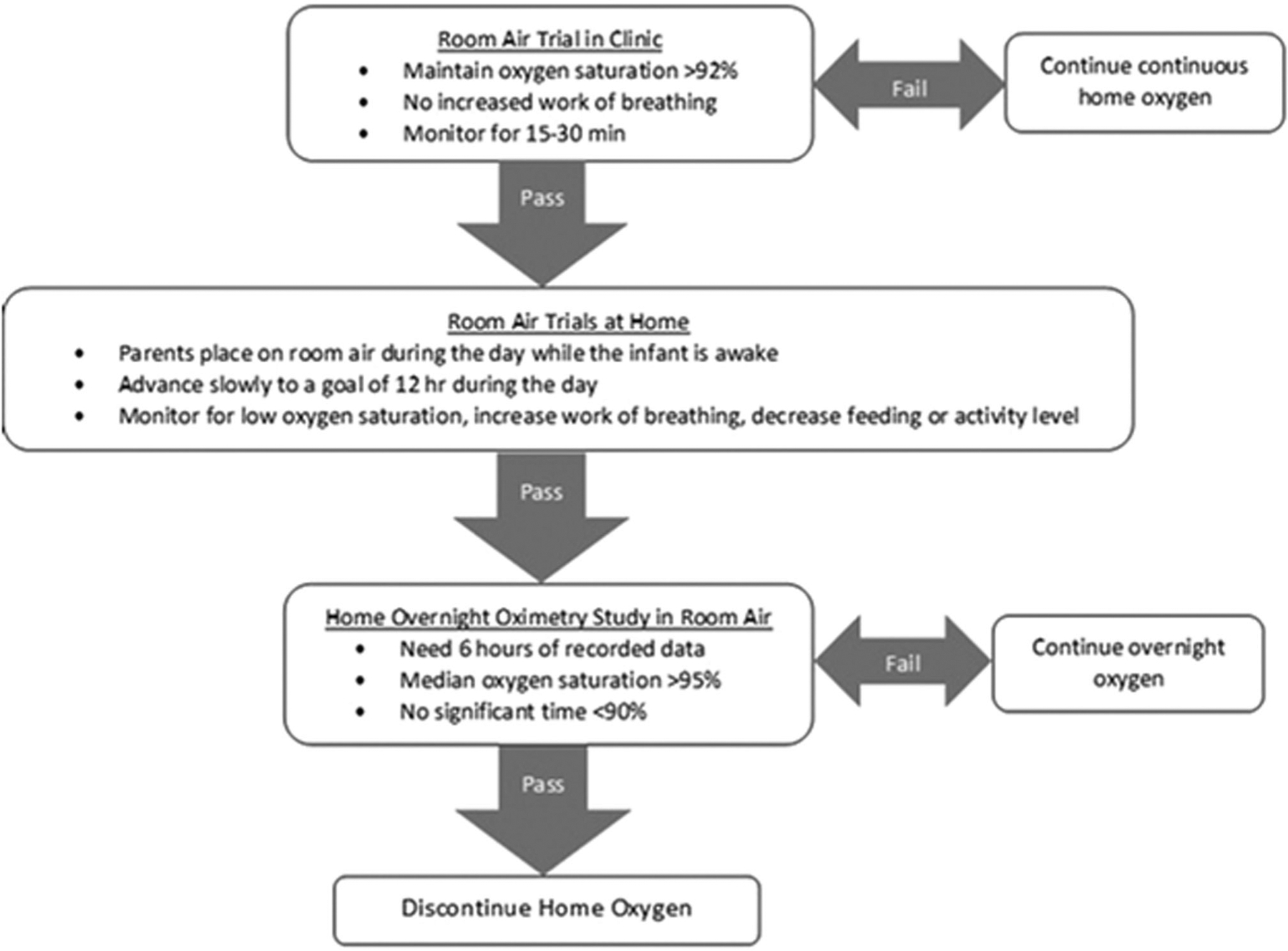

In our BPD clinic, both the NICU and referral groups are managed beginning around 4–6 weeks after NICU discharge by a single pediatric pulmonary care team, using a home oxygen weaning algorithm (Figure 1). Infants who pass a room air trial in clinic are followed every 4–6 weeks until home oxygen is discontinued. Infants who do not pass a room air trial in clinic are followed every 2–3 months; after a room air trial is passed, they are followed every 4–6 weeks until they are off oxygen. Successful weaning from oxygen is confirmed by a home oximetry trial, performed with the Respironics 920 M Plus or Nonin 2500 PalmSTAT pulse oximetry monitors, and interpreted by our team.

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for weaning home oxygen. The NICU and referral groups were seen in BPD clinic 4–6 weeks following NICU discharge. At the first visit the infants were placed on room air and observed for 15–30 min. If they fail, then they are followed up in 2–3 months and the room air trail is repeated. If they pass, then room air trials at home are started and they are followed up ever 4–6 weeks until oxygen is discontinued. The parents gradually extend the homeroom air trials with a goal of 12 h during the day. Once the infant is tolerating 12 h on room air during the day, the parents call pulmonary and a home overnight pulse oximetry study is performed on room air. Oxygen is discontinued when the infant has passed the home overnight pulse oximetry study. If they fail the home oximetry study, then it is repeated in 4–6 weeks. BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

Our primary exposure variable of interest was the closest capillary blood gas pCO2 before NICU discharge. This information was available both on infants discharged from our NICU and those referred from other hospitals because we record predischarge blood gas data as part of our clinic intake. For infants in our NICU group, we evaluated a secondary exposure variable of pCO2 at 36 weeks corrected age for all infants still receiving respiratory support, as part of pulmonary hypertension screening. In our NICU, this blood gas information is used to optimize respiratory support for infants with echocardiographic evidence of pulmonary hypertension, per consensus guidelines by the Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension Network.13 For the referral group, we were unable to obtain information on pCO2 at 36 weeks post menstrual age and subsequent management practices. We included this secondary exposure variable because we thought pCO2 obtained at a standardized time point may be more reflective of NICU illness severity.4

Our primary outcome was readmission by 1 year after NICU discharge for respiratory reasons, defined as overnight admission with increased respiratory symptoms as identified by manual chart review. Secondary outcomes included other respiratory hospital encounters, medical management related to BPD, and home oxygen weaning. Hospital encounter outcomes included intubation, readmission to an intensive care unit, readmission for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or influenza, visits to the emergency room, and total duration of inpatient admissions; these encounters were rare outside of our health system but if they occurred, we abstracted details from the clinic record. Medical respiratory management outcomes included receiving systemic steroids or increased diuretics, bronchodilators, or inhaled corticosteroids above baseline; these were recorded from all clinic, inpatient or emergency department encounters. Home oxygen outcomes included the total duration of home oxygen in weeks post-NICU discharge, any increases in home oxygen flow above baseline, and the number of failed room air trials in clinic, home oximetry trials and sleep studies. We also recorded the number of BPD clinic visits in the first year following discharge, number of missed clinic visits and the number of times oxygen was weaned without the physician’s input.

We reviewed patients’ NICU charts for demographic data and neonatal variables including sex, multiple gestation, gestational age at birth, birth weight, antenatal steroid use, surfactant use, patent ductus arteriosus ligation, BPD severity in grades as proposed by Jensen et al.3; the number of days of ventilation, noninvasive ventilation, and supplemental oxygen. At discharge, we recorded the corrected gestational age at discharge, amount of home oxygen, and receipt of diuretics, bronchodilators, and inhaled corticosteroids. Infants referred to our institution from other NICUs were limited in the availability of some neonatal variables by what was abstracted from the referring NICU discharge summary as part of our clinic intake.

2.1 |. Statistical analysis

We compared the distribution of predischarge pCO2 between the NICU and referral groups. We then compared the differences between predischarge pCO2 by NICU variables; we repeated these comparisons using 36-week pCO2 for the NICU group. Similarly, we compared the differences between pCO2 and outcomes. For all bivariable comparisons, we used sign rank or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate. For the primary outcome of respiratory readmissions, we evaluated the association between pCO2 and readmission before and after adjustment for other NICU illness covariates. We chose illness covariates for inclusion in the model based on both bivariable analysis and the clinical possibility that they could impact the association between pCO2 and readmission; these included gestational age, BPD severity, ductus arteriosus ligation, and diuretic use.3,14 To further describe our secondary outcome of duration of home oxygen use, we considered both corrected gestational age at discontinuation of home oxygen in categorized groups, as well as a survival curve of weeks post-NICU discharge on home oxygen. For all analyses, p < .05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children’s Wisconsin.

3 |. RESULTS

Ninety-two infants were discharged from our NICU; 71 were discharged with home oxygen. Our referral group included 54 patients discharged from other NICUs that were seen in pulmonary clinic for home oxygen management. Of the 125 infants evaluated in our home oxygen clinic, five patients were lost to follow up between NICU discharge and 1 year, leaving 120 patients as our final cohort for analysis. The median gestational age of the cohort was 27 weeks (interquartile range [IQR], 23–30); 56 were females and 64 were males. The corrected median gestational age at discharge was 38 weeks (IQR, 37–40) for infants with Grade 1 BPD; 43 weeks (IQR, 40–46) for infants with Grades 2–3 BPD, and 39 weeks (IQR, 38–41) for infants with BPD of unknown grade referred to our clinic from other NICUs.

The median pCO2 at NICU discharge was 55 mmHg (IQR, 51–58), with no significant differences between the NICU group (median, 55; IQR, 52–59) or the referral group (median, 55; IQR, 50–58; p = .344). Only 18 infants from either the NICU group (n = 11) or the referral group (n = 7) were discharged home with pCO2 ≥ 60 mmHg. Table 1A displays associations between predischarge pCO2 and NICU clinical illness characteristics. Infants with higher discharge pCO2 were born at an earlier gestational age and had more days of mechanical ventilation; at discharge they were prescribed higher liter flow of oxygen and more bronchodilators. Otherwise, there were no other significant associations between discharge pCO2 and NICU variables, either in the total cohort, or in the NICU and referral groups when examined separately.

TABLE 1.

Bivariable associations between pCO2 and NICU illness characteristics

| 1A: pCO2 at discharge NICU +referral cohort (n = 120) | 1B: pCO2 at 36 weeks NICU cohort (n = 67) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N | Median (mmHg) | IQR (mmHg) | p value | Median (mmHg) | IQR (mmHg) | p value |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 56 | 55 | 52–59 | .385 | 62 | 54–65 | .147 |

| Male | 64 | 56 | 49–58 | 57 | 53–63 | ||

| Gestational age | |||||||

| 22–24 | 30 | 57 | 54–59 | .013 | 61 | 56–67 | .029 |

| 25–28 | 70 | 54 | 51–59 | 60 | 54–64 | ||

| 29–31 | 20 | 51 | 48–56 | 53 | 49–57 | ||

| Birth weight (g) | |||||||

| <1000 | 84 | 56 | 52–59 | .112 | 61 | 54–65 | .029 |

| 1000–1499 | 30 | 54 | 49–57 | 56 | 49–62 | ||

| >1500 | 6 | 56 | 49–58 | 54 | 53–54 | ||

| BPD severity | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 37 | 56 | 53–58 | .105 | 58 | 53–63 | .001 |

| Grade 2–3 | 30 | 56 | 52–59 | 61 | 57–65 | ||

| Unknown | 53 | 54 | 50–58 | 54 | 49–59 | ||

| Multiple gestation | |||||||

| No | 92 | 55 | 51–59 | .817 | 59 | 54–63 | .604 |

| Yes | 28 | 55 | 53–57 | 61 | 50–64 | ||

| Antenatal steroids | |||||||

| No | 10 | 57 | 49–63 | .423 | 62 | 57–63 | .546 |

| Yes | 88 | 55 | 52–58 | 59 | 53–63 | ||

| Surfactant | |||||||

| No | 8 | 54 | 54–57 | .997 | 54 | 50–57 | .129 |

| Yes | 100 | 56 | 51–58 | 60 | 54–64 | ||

| PDA ligation | |||||||

| No | 102 | 56 | 51–59 | .522 | 57 | 52–63 | .013 |

| Yes | 18 | 54 | 52–58 | 62 | 58–72 | ||

| Ventilation days | |||||||

| 0 | 12 | 52 | 48–56 | .042 | 53 | 52–57 | .005 |

| 1–29 | 49 | 54 | 49–58 | 57 | 51–62 | ||

| 30–59 | 31 | 56 | 54–59 | 63 | 60–65 | ||

| >60 | 20 | 57 | 53–59 | 60 | 57–67 | ||

| NIV days | |||||||

| 0–14 | 29 | 53 | 50–58 | .441 | 59 | 51–64 | .592 |

| 15–29 | 25 | 56 | 52–59 | 57 | 54–62 | ||

| 30–44 | 28 | 56 | 51–58 | 60 | 52–64 | ||

| >44 | 19 | 56 | 49–58 | 60 | 57–64 | ||

| Oxygen days | |||||||

| 0–29 | 2 | 48 | 47–48 | .070 | 48 | 47–48 | .001 |

| 30–59 | 17 | 53 | 50–56 | 54 | 51–57 | ||

| 60–89 | 31 | 57 | 52–62 | 58 | 52–62 | ||

| 90–119 | 32 | 56 | 52–59 | 60 | 55–64 | ||

| 120–149 | 34 | 55 | 51–57 | 62 | 60–65 | ||

| >149 | 9 | 58 | 55–58 | 69 | 60–73 | ||

| Family history of asthma | |||||||

| No | 52 | 52 | 51–57 | .066 | 58 | 53–62 | .683 |

| Yes | 66 | 66 | 51–59 | 60 | 54–64 | ||

| At discharge: | |||||||

| Corrected gestational age | |||||||

| 35–39 | 63 | 55 | 51–58 | .638 | 55 | 52–60 | .001 |

| 40–44 | 43 | 55 | 52–57 | 62 | 54–65 | ||

| >44 | 14 | 58 | 51–59 | 63 | 61–73 | ||

| Home oxygen (L/min) | |||||||

| ≤l/8 | 35 | 52 | 48–56 | .002 | 57 | 54–64 | .823 |

| 1/4 | 43 | 54 | 51–57 | 59 | 53–63 | ||

| 1/2 | 34 | 58 | 55–61 | 60 | 54–65 | ||

| 3/4 | 8 | 57 | 54–62 | 61 | 55–67 | ||

| Diuretics | |||||||

| No | 45 | 54 | 52–58 | .476 | 53 | 50–57 | <.001 |

| Yes | 75 | 56 | 51–59 | 62 | 58–65 | ||

| Bronchodilators | |||||||

| No | 84 | 54 | 51–57 | .028 | 57 | 53–63 | .259 |

| Yes | 36 | 57 | 53–62 | 62 | 55–64 | ||

| Inhaled corticosteroids | |||||||

| No | 95 | 55 | 51–58 | .810 | 58 | 54–63 | .246 |

| Yes | 25 | 56 | 51–58 | 63 | 52–66 | ||

Note: “NICU group” refers to a group of patients recruited in a prospective study in our NICU, discharged with home oxygen therapy. “Referral group” refers to infants discharged from other local level III NICUs referred to our pulmonary clinic for management of home oxygen therapy. Table 1a displays associations between predischarge pCO2 and NICU illness characteristics of both NICU and referral groups. Table 1b displays associations between 36-week pCO2 and NICU illness characteristics of the NICU group. p values represent Kruskal-Wallis or sign-rank tests.

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; IQR, interquartile range; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; NIV, noninvasive ventilation.

The median pCO2 at 36 weeks corrected gestational age for the NICU group was 59 (IQR, 53–63). Table 1B displays associations between 36-week pCO2 and NICU illness characteristics. Higher 36-week pCO2 was associated with earlier gestational age, lower birth weight, patent ductus arteriosus ligation, severe BPD, more days of mechanical ventilation, and more days of supplemental oxygen while in the NICU. At discharge, a higher 36-week pCO2 was associated with later corrected gestational age at discharge and discharge with diuretics.

For our primary outcome of readmissions, 23% of infants experienced at least one respiratory readmission in the year after NICU discharge. There was no significant association between either predischarge or 36-week pCO2 and respiratory readmission. Even after logistic regression adjusting for other significant measures of illness severity including gestational age, ductus arteriosus ligation, BPD severity, and diuretic use, neither predischarge nor 36-week pCO2 were associated with readmissions (Table 2). Of those admissions, 19% were associated with RSV and none were associated with influenza.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable model of associations between pCO2 and 1-year readmission

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value |

| pCO2 at discharge | 1.01 | 0.93–1.10 | .77 | 0.99 | 0.92–1.09 | .989 |

| Gestational age | ||||||

| 23–24 | 1 | 0.27–1.89 | .47 | 1 (ref) | 0.29–2.93 | .88 |

| 25–29 | 0.70 | 0.0564–4.747 | .560 | 0.92 | 0.13–3.98 | .71 |

| 29–31 | 0.517 | 0.72 | ||||

| PDA ligation | ||||||

| No | 1 | 0.37–3.44 | .821 | 1 (ref) | 0.16–2.28 | .48 |

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.62 | ||||

| BPD severity | ||||||

| Grade 1 | 1 | 1.01–10.8 | .049 | 1 (ref) | 0.49–7.77 | .344 |

| Grades 2–3 | 3.30 | 0.53–5.33 | .372 | 1.95 | 0.39–4.94 | .618 |

| Not determined (referral hospital) | 1.69 | 1.38 | ||||

| Diuretics | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1.39–13.4 | .012 | 1 (ref) | 1.12–16.6 | .033 |

| Yes | 4.31 | 4.31 | ||||

| pCO2 at 36 weeks | 0.97 | 0.90–1.05 | .518 | 0.91 | 0.81–1.02 | .082 |

| Gestational age | ||||||

| 23–24 | 1 | 0.27–1.82 | .47 | 1 (ref) | 0.19–3.48 | .781 |

| 25–29 | 0.70 | 0.11–2.00 | .31 | 0.81 | 0.02–3.61 | .326 |

| 29–31 | 0.47 | 0.28 | ||||

| PDA ligation | ||||||

| No | 1 | 0.37–3.44 | .821 | 1 (ref) | 0.29–6.71 | .683 |

| Yes | 1.14 | 1.39 | ||||

| BPD severity | ||||||

| Grade 1 | 1 | 1.01–10.8 | .049 | 1 (ref) | 0.40–8.41 | .440 |

| Grades 2–3 | 3.30 | 0.53–5.33 | .372 | 1.83 | ||

| Not determined (referral hospital) | 1.69 | N/A | ||||

| Diuretics | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1.39–13.4 | 0.012 | 1 (ref) | 0.71–23.9 | .116 |

| Yes | 4.31 | 4.11 | ||||

Note: This table shows the model evaluating association with predischarge pCO2 for both NICU and referral groups and shows 36-week pCO2, for the NICU group alone. Covariates that were significant at p < .1 in bivariable analysis were considered as candidates for inclusion in the multivariable models. Variables were retained in the model and considered significant if p < .05.

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CI, confidence interval; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus.

Associations between predischarge and 36-week pCO2 and secondary outcomes are shown in (Table 3). There was no association between either predischarge or 36-week pCO2 and secondary hospital encounter outcomes of emergency department visits, number or duration of admissions, intensive care unit admissions, or intubation. For respiratory medical management, a higher predischarge pCO2 was associated with receipt of systemic steroids and being prescribed new or increased inhaled corticosteroids.

TABLE 3.

Associations between pCO2 and secondary outcomes

| 3A: pCO2 at discharge NICU + referral cohort (n = 120) | 3B: pCO2 at 36 weeks NICU cohort (n = 67) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N | Median (mmHg) | IQR (mmHg) | p value | Median (mmHg) | IQR (mmHg) | p value |

| Admissions | |||||||

| No | 93 | 55 | 51–58 | .374 | 60 | 54–64 | .410 |

| Yes | 27 | 57 | 50–59 | 56 | 51–63 | ||

| PICU admission | |||||||

| No | 109 | 55 | 51–58 | .461 | 60 | 53–64 | .652 |

| Yes | 11 | 57 | 54–58 | 57 | 54–62 | ||

| Required intubation | |||||||

| No | 115 | 57 | 49–59 | .816 | 62 | 51–65 | .815 |

| Yes | 5 | 57 | 53–58 | 54 | 54–57 | ||

| Total duration of admission | |||||||

| 1–7 | 16 | 56 | 48–59 | .290 | 54 | 51–63 | .311 |

| 8–30 | 6 | 58 | 57–61 | 65 | 57–73 | ||

| >30 | 5 | 55 | 52–57 | 54 | 54–72 | ||

| ED visits | |||||||

| No | 86 | 54 | 51–58 | .098 | 60 | 53–64 | .231 |

| Yes | 34 | 57 | 53–59 | 57 | 52–63 | ||

| Systemic steroids on admission, ED, or clinic | |||||||

| No | 99 | 54 | 50–58 | .020 | 60 | 53–64 | .724 |

| Yes | 21 | 57 | 55–59 | 57 | 54–63 | ||

| New/increased home bronchodilators from admission, ED, or clinic | |||||||

| No | 96 | 54 | 51–58 | .100 | 60 | 52–64 | .854 |

| Yes | 24 | 57 | 54–59 | 57 | 54–63 | ||

| New/increased inhaled steroids from admission, ED, or clinic | |||||||

| No | 92 | 54 | 49–58 | .004 | 60 | 53–63 | .854 |

| Yes | 28 | 57 | 55–59 | 59 | 54–65 | ||

| New/increased diuretics from admission, ED, or clinic | |||||||

| No | 115 | 55 | 51 | .077 | 60 | 53–64 | .470 |

| Yes | 5 | 58 | 57 | 56 | 54–57 | ||

| New/increased home oxygen after admission, ED, or clinic | |||||||

| No | 97 | 55 | 51–58 | .534 | 60 | 53–63 | .780 |

| Yes | 23 | 57 | 51–59 | 60 | 54–64 | ||

| Failed room air trials | |||||||

| Pass | 81 | 54 | 49–57 | <.001 | 57 | 52–63 | .024 |

| Fail | 34 | 59 | 56–62 | 62 | 57–67 | ||

| Failed overnight oximetry study | |||||||

| Pass | 85 | 54 | 50–58 | .659 | 57 | 53–63 | .003 |

| Fail | 24 | 55 | 51–60 | 64 | 63–67 | ||

| Sleep study performed | |||||||

| No | 116 | 55 | 51–58 | .187 | 60 | 54–63 | .800 |

| Yes | 4 | 59 | 55–64 | 61 | 52–67 | ||

| Number of clinic visits | |||||||

| 0 | 2 | 58 | 58–58 | 56 | 52–62 | ||

| 1–2 | 50 | 52 | 49–56 | <.001 | 61 | 55–65 | .024 |

| 3–8 | 68 | 57 | 54–60 | ||||

| Any no shows in clinic | |||||||

| No | 105 | 56 | 51–59 | .362 | 60 | 54–63 | .569 |

| Yes | 15 | 54 | 52–55 | 56 | 48–72 | ||

| Weaned without physician input | |||||||

| No | 89 | 55 | 51–58 | .324 | 60 | 53–64 | .349 |

| Yes | 31 | 57 | 52–59 | 57 | 54–62 | ||

| cGA oxygen discontinued (months) | |||||||

| <6 | 68 | 54 | 49–57 | 54 | 51–61 | ||

| 6–11 | 30 | 56 | 54–59 | .154 | 62 | 57–65 | .006 |

| ≥12 | 2 | 55 | 54–55 | 66 | 58–73 | ||

Note: “NICU group” refers to a group of patients recruited in a prospective study in our NICU, discharged with home oxygen therapy. “Referral group” refers to infants discharged from other local level III NICUs referred to our pulmonary clinic for management of home oxygen therapy. p values represent Kruskal-Wallis or sign-rank tests.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

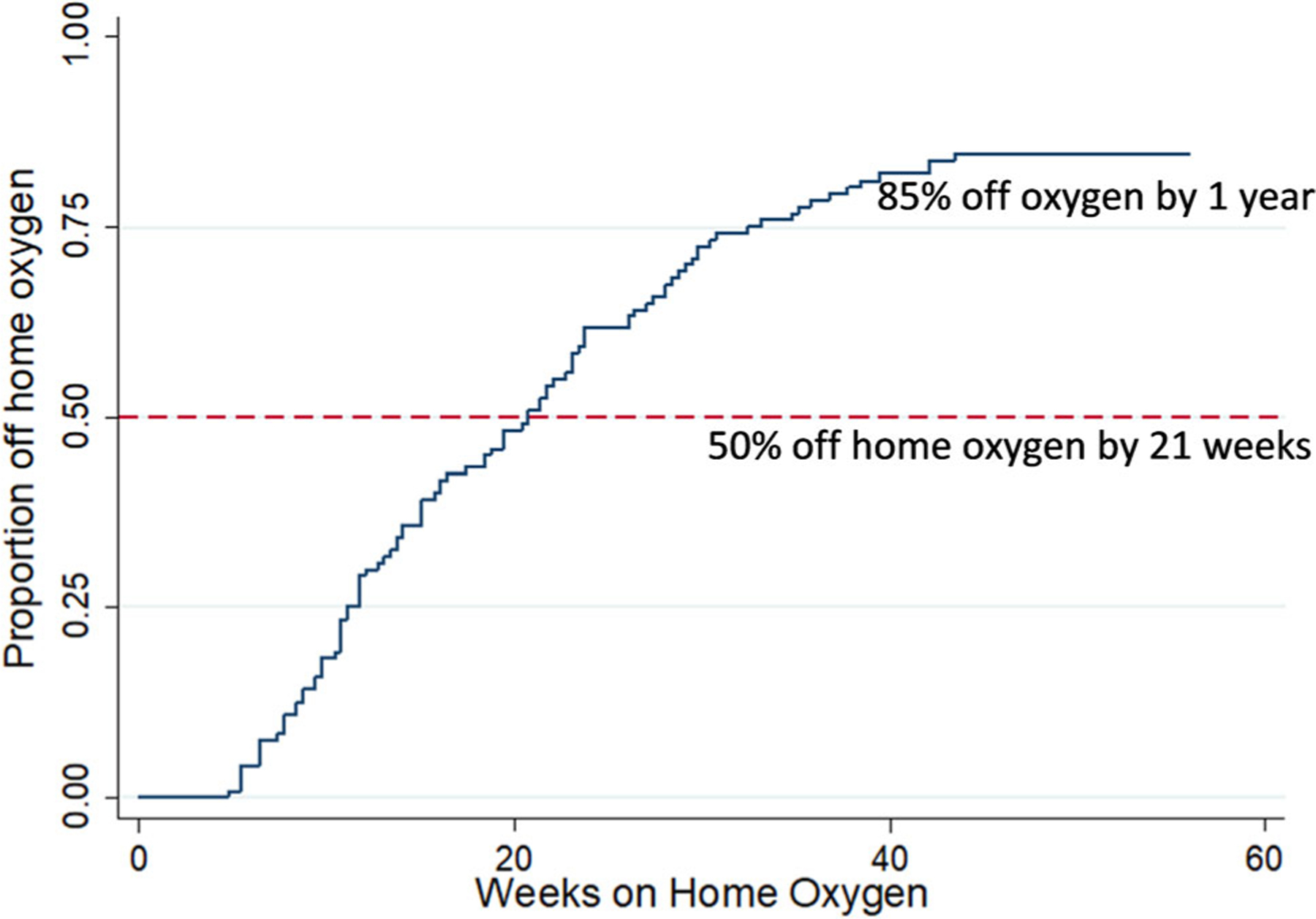

For home oxygen management, higher 36-week pCO2 was associated with later corrected gestational age at which oxygen was discontinued (Figure 2), longer duration of home oxygen in weeks, failing more clinic room air trials and home overnight oximetry studies (Table 3). Higher predischarge pCO2 was only associated with failing clinic room air trials. Infants with more clinic visits in the year after NICU discharge had higher 36-week and predischarge pCO2, but there were no differences in missed appointments or in weaning oxygen without physician input.

FIGURE 2.

pCO2 and corrected age at discontinuation of home oxygen. This graph shows how pCO2 was associated with the age at discontinuation of oxygen. The y axis shows pCO2 and the x axis shows corrected age at discontinuing oxygen. The box shows the median predischarge pCO2; circles show median 36-week pCO2.Vertical bars indicate interquartile range. p values indicate nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests between groups

The median time to discontinuing home oxygen for all infants was 21 weeks following NICU discharge; 85% of patients were off oxygen by 1 year following NICU discharge (Figure 3). For the 19 infants still receiving oxygen at 1 year following NICU discharge, 12 had experienced hospital admissions, ER visits, and other significant respiratory complications. Four of those infants also had pulmonary hypertension that required medical management. The other seven still requiring supplemental oxygen at 1 year following NICU discharge had poor outpatient follow-up.

FIGURE 3.

Duration of home oxygen. This figure shows a survival curve of the timing of discontinuation of home oxygen in our cohort. The y axis shows the proportion of infants discontinuing home oxygen; the x axis shows the number of weeks after neonatal intensive care unit discharge on home oxygen

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study describes respiratory healthcare utilization in the year following NICU discharge for infants with BPD discharged with home oxygen, in the setting of a standardized home oxygen weaning guideline. We found that predischarge pCO2 was not associated with a higher risk of readmission or other hospital respiratory encounters but was associated with prescription of systemic steroids and inhaled corticosteroids. Higher pCO2 at 36 weeks correlated with a longer duration of home oxygen or later corrected gestational age at which oxygen was discontinued.

Infants with BPD are at increased risk for hospital readmission and other healthcare utilization. Kovesi et al.4 previously showed that an elevated capillary pCO2 before discharge was associated with an increased risk of readmission or a severe adverse event, defined as late pulmonary hypertension, reintubation or death after discharge. Since that publication, we have talked to colleagues at many institutions who, like our institution, recommend discharge after a pCO2 is less than 60; this is the first study of which we are aware that evaluates outcomes in the setting of such a recommendation. In our study, we did not find that capillary pCO2 at discharge or at 36 weeks was associated with more readmissions or reintubations; no infants in our cohort died after discharge and we had few infants with late pulmonary hypertension. The lack of association between pCO2 and readmission could be secondary to our recommendation to discharge infants after the pCO2 is <60 mmHg. We saw the same non-association between pCO2 and readmission in the referral group, but similar to our NICU group, few referral infants had high pCO2s before discharge. Considering our readmission rate for infants discharged with home oxygen therapy was not high, it is possible that close outpatient follow up was successful in controlling symptoms that otherwise may have led to readmissions.15,16 Infants were seen in pulmonary clinic 4–6 weeks following discharge from the NICU, and then every 4–6 weeks to 2–3 months until they were off supplemental oxygen. It has been noted that outpatient management explains some variation in readmission rates for premature infants.16,17 For infants with BPD discharged with home oxygen, one example of close outpatient management may be the use of inhaled and systemic steroids, which we noted to be more common in infants with a higher predischarge pCO2. Ryan et al.9 similarly found in the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program that inhaled steroids and bronchodilators increased over the first year. It possible that outpatient management such as early use of inhaled or systemic steroids helps prevent our highest-risk patients from being admitted or presenting to the emergency room. This raises the issue of whether to continue our local recommendation to delay discharge for infants with higher pCO2. Based on our findings to date, we cannot broadly recommend predischarge pCO2 in criteria for safe discharge of infants with BPD. At our institution, the time to discharge for infants with BPD is still similar or shorter than other children’s hospital institutions, so changing this recommendation would likely have a relatively small impact on NICU length of stay.15 But if close outpatient follow-up can mitigate some potential risks, there may be benefits to individual patients by facilitating earlier discharge. Future implementation and quality improvement work will be needed to determine best practices moving forward.

Clinical practice guidelines of the American Thoracic Society recommend home oxygen therapy for infants with BPD who have chronic hypoxemia; home oxygen therapy is used in at least half of infants with BPD discharged from U.S. NICUs.18–21 After NICU discharge, however, there are few published guidelines for the close monitoring required to wean home oxygen therapy in the outpatient setting.20,22,23 We developed an oxygen weaning protocol in 2012 to standardize the care of infants being discharged with home oxygen in our clinic. Using this guideline, we were able to effectively wean home oxygen using home oximetry studies. Only three patients received sleep studies due to concerns for the quality of the home oximetry study. Our use of this clinical guideline enabled us to assess duration of home oxygen use as a secondary outcome in this study. We found that a higher pCO2 at 36 weeks corrected age, but not predischarge, was associated with a longer duration of home oxygen or later corrected gestational age at which oxygen was discontinued. We noted that pCO2 at 36 weeks was correlated with other measures of NICU illness severity, such as gestational age, days of mechanical ventilation, and BPD severity. Kaempf et al.24 have previously shown that a 36-week capillary blood gas pCO2 correlated with NICU illness severity; our findings suggest that in the setting of a home oxygen weaning guideline, NICU illness measures such as 36-week pCO2 may be used to predict duration of outpatient home oxygen therapy. Rhein et al.25 recently reported results of a randomized clinical trial of two different strategies to wean home oxygen in the outpatient setting; they noted that infants whose parents reported more home weaning attempts were safely weaned from oxygen faster. In this context, our findings present an opportunity to use NICU illness measures to tailor outpatient management and counsel families in a more individualized fashion. If parents have a better idea of the expected duration of home oxygen therapy for their infant, it may influence them to participate more actively in the home oxygen weaning process.

Strengths of this study include the level of clinical detail available in a single center, the use of an outpatient clinical guideline and high degree of follow-up. There are several limitations. The biggest limitation was that this was a single-center study with a general recommendation not to discharge infants until pCO2 < 60 mmHg; we tried to examine associations between predischarge pCO2 and outcomes from referral NICUs, but in a medium-sized referral area those NICUs may already follow a practice similar to our own. We cannot determine from the chart review what led to decisions regarding NICU discharge. Even in the cohort from our own NICU, although outpatient oxygen weaning follows a guideline, NICU weaning of respiratory support is not protocolized; we were unable to determine how much of infants’ NICU length of stay was attributable to our guidelines regarding pCO2. Although our clinic follows a protocol for follow-up of infants with home oxygen, we were not able to control the exact timing of when appointments were made for each family that may affect the exact duration of home oxygen. We tried to mitigate this somewhat by also evaluating proxy measures of ability to wean home oxygen such as room air trials in clinic. For future studies of oxygen discontinuation, we will delineate between the providers approval to discontinue home oxygen and when the oxygen is removed from the home. We were able to collect detailed data on readmissions including diagnosis of RSV and influenza; however, because infants receive RSV prophylaxis and vaccines in multiple different healthcare systems, we were unable to determine the rates of RSV prophylaxis or influenza vaccination.

In conclusion, we found that pCO2 before NICU discharge or at 36 weeks corrected age was not associated with differences in one-year respiratory readmissions. Higher pCO2 at 36 weeks was associated with later corrected gestational age at which oxygen was discontinued, as well as longer duration of home oxygen therapy. In the setting of an outpatient oxygen weaning protocol, measures of neonatal illness severity at 36 weeks such as pCO2 may be useful in communicating expectations for home oxygen therapy to families. The association between predischarge pCO2 and subsequent healthcare utilization, including duration of home oxygen therapy requires further study, especially as hospitals look toward the earlier discharge of preterm infants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

K23 HL136525 (JL) and the Children’s Research Institute (JL).

Funding information

Joanne Lagatta, Grant/Award Number: K23 HL136525; Children`s Research Institute

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jensen EA, Schmidt B. Epidemiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2014;100(3):145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abman SH, Collaco JM, Shepherd EG, et al. Interdisciplinary care of children with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2017; 181:12–28 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen EA, Dysart K, Gantz MG, et al. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants. An evidence-based approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(6):751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovesi T, Abdurahman A, Blayney M. Elevated carbon dioxide tension as a predictor of subsequent adverse events in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Lung. 2006;184(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith VC, Zupancic JAF, McCormick MC, et al. Rehospitalization in the first year of life among infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2004;144(6):799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenough A Home oxygen status and rehospitalisation and primary care requirements of infants with chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86(1):40–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham CK, McMillan JA, Gross SJ. Rehospitalization for respiratory illness in infants of less than 32 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics. 1991;88(3):527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Long-term outcomes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(6):391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan RM, Keller RL, Poindexter BB, et al. Respiratory medications in infants < 29 weeks during the first year postdischarge: the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP) consortium. J Pediatr. 2019;208:148–155 e143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thome UH, Dreyhaupt J, Genzel-Boroviczeny O, et al. Influence of PCO2 control on clinical and neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants. Neonatology. 2018;113(3): 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abman SH. Medical progress series: bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 50 years—an introduction. J Pediatr. 2017;188:18–18 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan U, Feinstein JA, Adatia I, et al. Evaluation and management of pulmonary hypertension in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2017;188:24–34 e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouillette RT, Waxman DH. Evaluation of the newborn’s blood gas status. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry. Clin Chem. 1997; 43(1):215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagatta J, Murthy K, Zaniletti I, et al. Home oxygen use and 1-year readmission among infants born preterm with bronchopulmonary dysplasia discharged from Children’s Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Units. J Pediatr. 2020;220:40–48 e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMauro SB, Jensen EA, Bann CM, et al. Home oxygen and 2-year outcomes of preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 2019;143:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorch SA, Baiocchi M, Silber JH, Even-Shoshan O, Escobar GJ, Small DS. The role of outpatient facilities in explaining variations in risk-adjusted readmission rates between hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(1):24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ejiawoko A, Lee HC, Lu T, Lagatta J. Home oxygen use for preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia in California. J Pediatr. 2019;210:55–62 e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens TP, Finer NN, Carlo WA, et al. Respiratory outcomes of the surfactant positive pressure and oximetry randomized trial (SUPPORT). J Pediatr. 2014;165(2):240–249 e244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagatta J, Clark R, Spitzer A. Clinical predictors and institutional variation in home oxygen use in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2012; 160(2):232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes D Jr., Wilson KC, Krivchenia K, et al. Home oxygen therapy for children. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(3): e5–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson C, Hillman NH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: when the very preterm baby comes home. Mo Med. 2019;116(2):117–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palm K, Simoneau T, Sawicki G, Rhein L. Assessment of current strategies for weaning premature infants from supplemental oxygen in the outpatient setting. Adv Neonatal Care. 2011;11(5): 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaempf JW, Campbell B, Brown A, Bowers K, Gallegos R, Goldsmith JP. PCO2 and room air saturation values in premature infants at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 2008; 28(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhein HAF LM, Sheils C, Hartman T, White H, RHO Study Group. Use of home oximetry recording decreases duration of supplemental oxygen in premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019:199. [Google Scholar]