Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is often accompanied by chronic diseases, including mental health problems. We aimed at studying mental health comorbidity prevalence in T2D patients and its association with T2D outcomes through a retrospective, observational study of individuals of the EpiChron Cohort (Aragón, Spain) with prevalent T2D in 2011 (n = 63,365). Participants were categorized as having or not mental health comorbidity (i.e., depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and/or substance use disorder). We performed logistic regression models, controlled for age, sex and comorbidities, to analyse the likelihood of 4-year mortality, 1-year all-cause hospitalization, T2D-hospitalization, and emergency room visit. Mental health comorbidity was observed in 19% of patients. Depression was the most frequent condition, especially in women (20.7% vs. 7.57%). Mortality risk was higher in patients with mental health comorbidity (odds ratio 1.24; 95% confidence interval 1.16–1.31), especially in those with substance use disorder (2.18; 1.84–2.57) and schizophrenia (1.82; 1.50–2.21). Mental health comorbidity also increased the likelihood of all-cause hospitalization (1.16; 1.10–1.23), T2D-hospitalization (1.51; 1.18–1.93) and emergency room visit (1.26; 1.21–1.32). These results suggest that T2D healthcare management should include specific strategies for the early detection and treatment of mental health problems to reduce its impact on health outcomes.

Subject terms: Diseases, Health care

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) currently represents a significant public health problem worldwide. This chronic multisystem disease results in a progressive deterioration of quality of life1, and has been described as one of the most important epidemics of the twenty-first century due to its steadily increasing prevalence2–4. According to the International Diabetes Federation, 463 million people worldwide (adults 20–79 years old) were living with T2D in 2019, and this number is expected to increase to 700 million by 20454. T2D is a chronic condition that poses a challenge for patients and their families, caregivers and health systems, due in part to potential complications that may lead to the overutilization of hospital and emergency services.

Rarely appearing in isolation, T2D is frequently accompanied by other chronic diseases; almost 90% of patients with T2D have at least another additional chronic condition (i.e., multimorbidity)5. The morbidity burden and the concurrence of certain chronic diseases may increase the risk of adverse health outcomes in T2D patients. The care and healthcare management of this large population group should, therefore, take into account the comorbidity that co-occurs. Conditions such as obesity, high blood pressure and high serum triglycerides are frequently observed in T2D patients as part of the so-called metabolic syndrome5. However, diabetes is not only accompanied by metabolic and cardiovascular conditions (i.e., concordant comorbidities of T2D), but also by discordant comorbidities like mental health problems, which originate particularly important adverse effects on the health of T2D patients1.

The association between T2D and mental health problems has been well documented6–13. The World Health Organization considers that depression is one of the leading causes of health deterioration and progression towards disability14; this condition has been associated with a higher risk of diabetes complications and increased health care services utilization among patients with T2D15,16. However, most studies published to the date have only focused on specific mental health comorbidities such as depression or anxiety, and less is known about the effect on T2D patients’ health of other kinds of mental health problems like schizophrenia or substance use disorder.

Identifying and treating mental health comorbidities in T2D patients should be a priority17. Thus, it is crucial to study how mental health problems affect T2D patients’ health in order to implement more effective diabetes management programmes and improve patients’ health outcomes. This study aimed to explore the prevalence of mental health comorbidty in a Spanish population cohort of T2D patients, and to analyse the specific effect of depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and schizophrenia on the following T2D outcomes: 4-year all-cause mortality, and 1-year all-cause hospitalization, T2D-hospitalization and emergency room visit.

Results

The EpiChron Cohort follows 1,070,762 adult users of the public health system of the Spanish region of Aragón. A total of 63,365 adults (46% women, mean age of 69.9 years) in the cohort had a diagnosis of T2D, resulting in a prevalence of 6%. Most of the patients with T2D had at least one more simultaneous chronic disease (Table 1), and approximately one in five individuals (19%) had concurrent mental health comorbidity. The proportion of women was significantly higher in the population with at least one mental health problem than in the group with no mental health comorbidity registered in the health records (62.5% vs. 42.1%, p < 0.001). The mean number of chronic comorbidities (excluding mental health ones) was significantly higher in patients with concurrent mental health comorbidities compared with those T2D patients free of mental health problems (4.91 ± 3.02 vs. 3.74 ± 2.55 chronic conditions, p < 0.001). More than 90% of patients with T2D and mental health comorbidity had at least two additional comorbidities, and only 2% of them had no other concurrent chronic disease.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the population with type 2 diabetes (T2D) based on the presence or not of mental health comorbidity.

| Characteristics | Total population (n = 63,365) | Without mental health comorbidity (n = 51,335) | With mental health comorbidity (n = 12,030) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 34,215 (54.0) | 29,707 (57.9) | 4508 (37.5) | |

| Female | 29,150 (46.0) | 21,628 (42.1) | 7522 (62.5) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean age (SD) | 69.9 (12.1) | 69.8 (12.2) | 70.2 (11.8) | 0.018 |

| Age groups (n, %) | < 0.001 | |||

| 18–44 | 1666 (2.6) | 1410 (2.75) | 256 (2.13) | |

| 45–64 | 18,445 (29.1) | 14,926 (29.1) | 3519 (29.3) | |

| 65–74 | 17,511 (27.6) | 14,283 (27.8) | 3228 (26.8) | |

| 75–84 | 19,537 (30.8) | 15,654 (30.5) | 3883 (32.3) | |

| ≥ 85 | 6206 (9.8) | 5062 (9.9) | 1144 (9.6) | |

| Additional comorbidities | ||||

| Mean number (SD) | 3.96 (2.7) | 3.74 (2.6) | 4.91 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| Number (n, %) | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 3020 (4.8) | 2746 (5.4) | 274 (2.3) | |

| 1 | 7117 (11.2) | 6317 (12.3) | 800 (6.7) | |

| 2 | 10,403 (16.4) | 8958 (17.4) | 1445 (12.0) | |

| 3 | 11,184 (17.6) | 9405 (18.3) | 1779 (14.8) | |

| 4 | 9668 (15.3) | 7818 (15.2) | 1850 (15.4) | |

| 5 | 7487 (11.8) | 5835 (11.4) | 1652 (13.7) | |

| ≥ 6 | 14,486 (22.9) | 10,256 (20.0) | 4230 (35.2) | |

SD standard deviation.

*p values correspond to the comparison of T2D patients with at least one diagnosis of mental health comorbidity vs. T2D patients with no mental health comorbidity; Chi-squared test and Mann–Whitney U test (non-parametric test) were used.

The most common mental health comorbidities among T2D patients were depression (13.6%) and anxiety (3.17%), both of them more frequent in women (Table 2). Substance use disorder was more frequent in men, mainly in adults up to 64 years old. The prevalence of depression increased with age, while anxiety, substance use disorder and schizophrenia were more frequent in the younger population.

Table 2.

Frequency and prevalence (%) of mental health comorbidity in the population with type 2 diabetes (n = 63,365) according to sex and age.

| Type of mental health comorbidity | Depression | Anxiety | Substance use disorder | Schizophrenia | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n, %) | 8628 (13.6) | 2008 (3.2) | 1279 (2.0) | 931 (1.5) | 12,030 (19.0) |

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Male | 2590 (7.6) | 730 (2.1) | 1125 (3.29) | 427 (1.25) | 4508 (13.2) |

| Female | 6038 (20.7) | 1278 (4.4) | 154 (0.53) | 504 (1.73) | 7522 (25.8) |

| Age interval, years (n, %) | |||||

| 18–44 | 129 (7.7) | 64 (3.8) | 49 (2.9) | 51 (3.1) | 256 (15.4) |

| 45–64 | 2178 (11.8) | 665 (3.6) | 659 (3.6) | 365 (2.0) | 3519 (19.1) |

| 65–74 | 2326 (13.3) | 533 (3.0) | 331 (1.9) | 233 (1.3) | 3228 (18.4) |

| 75–84 | 3066 (15.7) | 583 (3.0) | 206 (1.1) | 222 (1.1) | 3883 (19.9) |

| ≥ 85 | 929 (15.0) | 163 (2.6) | 34 (0.6) | 60 (1.0) | 1144 (18.4) |

The presence of mental health comorbidity was associated with an increased risk of all the T2D outcomes considered in this study. The risk of 4-year all-cause mortality was 1.24 times higher (odds ratio, OR 1.24; 95% confidence interval, CI 1.16–1.31) in patients with at least one concurrent mental health comorbidity, after controlling for sex, age and number of non-mental comorbidities and the presence of the other types of mental health comorbidities (Table 3). The magnitude of this effect was different for each mental health problem. Thus, mortality risk was 2.18 (CI 1.84–2.57) times higher in patients with a diagnosis of substance use disorder, 1.82 (CI 1.50–2.21) times higher in patients with schizophrenia, and 1.14 (CI 1.07–1.22) times higher in those with depression. On the contrary, the likelihood of mortality was not influenced by the presence of anxiety (OR 0.98; CI 0.85–1.13).

Table 3.

Effect of the presence of mental health comorbidity on 4-year all-cause mortality risk in patients with type 2 diabetes, calculated using two regression analysis models: presence of any mental health comorbidity (Model 1) or type of mental health comorbidity (Model 2).

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Mental health comorbidity, yes | 1.25 (1.19–1.32) | 1.24 (1.16–1.31) | < 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.14 (1.13–1.15) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 0.58 (0.55–0.60) | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 1.12 (1.12–1.13) | < 0.001 | |

| Model 2 | |||

| Depression | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | 1.14 (1.07–1.22) | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 0.95 (0.83–1.07) | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 0.769 |

| Substance use disorder | 1.30 (1.13–1.50) | 2.18 (1.84–2.57) | < 0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.17 (0.98–1.39) | 1.82 (1.50–2.21) | < 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.14 (1.13–1.15) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 0.59 (0.56–0.62) | < 0.001 | |

| Age | 1.12 (1.12–1.13) | < 0.001 | |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

*Adjusted for sex, age, number of non-mental comorbidities, and the presence of the other types of mental health comorbidities.

The simultaneous presence of mental health comorbidity in patients with T2D was associated with a 1.16 (CI 1.10–1.23) times higher risk of 1-year all-cause hospitalization (Table 4). The magnitude of this effect was again different depending on the specific type of mental health comorbidity. The likelihood of all-cause hospitalization was 1.12 (CI 1.05–1.19), 1.40 (CI 1.18–1.66) and 1.58 (CI 1.38–1.81) times higher in patients with depression, schizophrenia and substance use disorder, respectively, whereas it was not associated with the presence of anxiety (OR 1.04; CI 0.92–1.18). We observed similar results for the risk of hospitalization related to T2D, which increased on average 1.51 (CI 1.18–1.93) times when mental health comorbidity was present. Patients with a diagnosis of substance use disorder had the highest risk of T2D-related hospitalization, which was 1.79 (CI 1.05–3.06) times higher, followed by those with depression (OR 1.49; CI 1.14–1.96); whereas anxiety and schizophrenia were not associated with higher risk of T2D-hospitalization. The likelihood of visiting the emergency room was 1.26 (CI 1.21–1.32) times higher when mental health comorbidity was present. The size of this effect was significant for all the specific mental health problems studied, which increased this risk by 22% (OR 1.22; CI 1.16–1.29), 28% (OR 1.28; CI 1.17–1.42), 43% (OR 1.43; CI 1.27–1.61) and 28% (OR 1.28; CI 1.11–1.47) for depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and schizophrenia, respectively.

Table 4.

Effect of the presence of mental health comorbidity in patients with type 2 diabetes on 1-year risk of all-cause hospitalization, of T2D-hospitalization and of emergency visit room, calculated using two regression analysis models: presence of any mental health comorbidity (Model 1) or type of mental health comorbidity (Model 2).

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause hospitalization | |||

| Model 1 | |||

| Mental health comorbidity, yes | 1.35 (1.28–1.42) | 1.16 (1.10–1.23) | < 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.21 (1.20–1.22) | 1.19 (1.18–1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 0.71 (0.68–0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Depression | 1.33 (1.26–1.41) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 0.518 |

| Substance use disorder | 1.79 (1.57–2.04) | 1.58 (1.38–1.81) | < 0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.26 (1.07–1.49) | 1.40 (1.18–1.66) | < 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.21 (1.20–1.22) | 1.19 (1.18–1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 0.72 (0.69–0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) | < 0.001 |

| T2D-hospitalization | |||

| Model 1 | |||

| Mental health comorbidity, yes | 1.76 (1.39–2.23) | 1.51 (1.18–1.93) | 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.18 (1.15–1.21) | 1.16 (1.13–1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) | 0.72 (0.58–0.91) | 0.005 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.111 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Depression | 1.76 (1.35–2.28) | 1.49 (1.14–1.96) | 0.004 |

| Anxiety | 1.55 (0.93–2.56) | 1.27 (0.76–2.12) | 0.358 |

| Substance use disorder | 2.31 (1.37–3.88) | 1.79 (1.05–3.06) | 0.033 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.23 (0.55–2.77) | 1.25 (0.55–2.82) | 0.592 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.18 (1.15–1.21) | 1.16 (1.13–1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 0.008 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.089 |

| Emergency visit room | |||

| Model 1 | |||

| Mental health comorbidity, yes | 1.49 (1.43–1.55) | 1.26 (1.21–1.32) | < 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.18 (1.18–1.19) | 1.16 (1.16–1.17) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 1.18 (1.14–1.22) | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.100 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Depression | 1.49 (1.42–1.56) | 1.22 (1.16–1.29) | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.49 (1.36–1.64) | 1.28 (1.17–1.42) | < 0.001 |

| Substance use disorder | 1.54 (1.37–1.72) | 1.43 (1.27–1.61) | < 0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.23 (1.07–1.42) | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | 0.001 |

| Non-mental health comorbidities (number) | 1.18 (1.18–1.19) | 1.16 (1.16–1.17) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | 1.18 (1.14–1.22) | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.193 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | < 0.001 |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

*Adjusted for sex, age, number of non-mental comorbidities, and the presence of the other types of mental health comorbidities.

Discussion

This study shows that approximately one in every five T2D patients has at least one mental health problem (i.e., depression, anxiety, schizophrenia or substance use disorder). Our findings suggest that the presence of mental comorbidity in these patients is associated, to a greater or lesser extent, with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes. Although similar results have been reported in the literature, real-world data in this large-scale population study confirm the significant impact of mental health comorbidity on T2D outcomes.

Several studies have shown that comorbidity is associated with increased mortality in T2D patients and that this increase is higher when psychiatric compared with non-psychiatric comorbidities are present18,19. Diabetes represents a significant cause of long-term mortality by itself, and the increased risk of mortality in patients with mental health comorbidity has been well described19–21. In our study, a 24% higher likelihood of 4-year mortality observed in patients with mental health comorbidity could be because this kind of comorbidities negatively affects the quality of life and self-care, which can lead to more severe diabetes complications22. The negative emotional impact of living with diabetes, known as diabetes distress, has been associated with sub-optimal self-care and glycemic control23–26. In addition, some psychiatric drugs such as tricyclic antidepressants can cause metabolic syndrome and exert hyperglycemic effects, exacerbating the progression of T2D27.

Various mental health problems have been previously identified as important risk factors associated with poor outcomes in diabetic patients17,28. Depression is the most common mental health comorbidity in our study, especially in women, affecting approximately one in ten T2D patients. Depression prevalence has been shown to be higher in patients with T2D than in people free of diabetes; it is greater in women, although the odds ratio for depression in patients with T2D compared with those without is higher in men29. It has been discussed that a bidirectional relationship may exist between T2D and depression28,30–34. Many studies reported that patients with diabetes have a higher risk of developing depression22,29,31,33,35, up to two times higher than in the general population. A recent systematic review underlined that people with depression have a 32% higher risk for developing T2D36.

Our study reveals that T2D patients with depression have higher 4-year mortality risk than T2D patients without depression, as well as increased risk for hospitalization related or not to diabetes, and a higher likelihood of using emergency services. Concurrent depression in patients with T2D is associated with poor adherence to treatment, higher complication rates, and increased use of healthcare services15–17,37. A significant increase in coronary heart disease and cardiovascular mortality in patients with depression and T2D has also been reported, with significant differences between men and women, suggesting the importance of implementing cardiovascular preventive strategies in this population38–40.

Although many patients with diabetes and depression also have anxiety, anxiety can occur in type 1 or type 2 diabetic patients without comorbid depression, especially when diabetes is first diagnosed or when complications first occur17,41. In our study, anxiety is more prevalent in women, and its prevalence decreases with age. Anxiety symptoms have been associated with an increased risk of developing incident diabetes28; this could be partially due to biological changes (e.g., inflammation, metabolic disorders)42, and complex relationships between anxiety and other comorbidities (e.g., depression, obesity). Also, the relationship between diabetes and anxiety is probably bidirectional43; however, results are controversial44,45. In any case, anxiety is an important comorbidity to consider in people with T2D, as the simultaneous presence of these two conditions is associated with poor glycemic control46, obesity47, and increased diabetes complications28,48. In our study, we found that T2D patients who had anxiety also had a significantly higher risk of visiting an emergency service; however, we did not find significantly increased risk of mortality or hospitalization.

Although less prevalent than depression and anxiety, substance use disorder is the mental health comorbidity in our study with the highest associated risk of mortality, which was increased by 118%, and also of hospitalization (either all-cause or T2D-related) and use of emergency services. Substance use disorder is a disease that leads to an inability to control the use of a legal or illegal drug or medication. It is well known that intravenous drug use is associated with a severe and general deterioration of health outcomes and with an increased likelihood of premature death49. However, the specific impact of this mental health problem on T2D patients has not been sufficiently documented, and further longitudinal studies are needed to understand the diabetes onset and outcomes in relation to substance use disorder50. Unlike depression and anxiety, in which a bidirectional relationship between them and T2D has been established, substance use disorder has not been clearly identified as a potential cause or consequence of T2D. In any case, our results suggest that substance use disorder should deserve special attention in diabetic patients as it did increase the risk of all-cause hospitalization by 58%, and the risk of T2D-related hospitalization by 79%. This disorder could be especially important in a disease like diabetes, in which appropriate self-care and healthy lifestyles are crucial to avoid complications.

Schizophrenia, the less prevalent mental health comorbidity in our study, is somehow related to diabetes, since T2D has been found to be more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia than in the general population51. Some studies consider that schizophrenia itself should be further proposed as a causal factor for T2D due to the strongly demonstrated genetic predisposition to diabetes among people with this mental health problem52,53. Our results reveal that this disorder is associated with a higher risk of mortality and all-cause hospitalization. However, its presence was not specifically associated with a greater risk of hospitalization related to T2D. It is well known that antipsychotics are associated with an increased risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus53. Excess mortality and all-cause hospitalizations could be explained by aggravating factors for T2D onset and poor diabetes management present in individuals with schizophrenia, such as excessive sedentary lifestyle, social determinants, adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs or limited access to medical care53,54.

Diabetes is considered an ambulatory care sensitive condition where effective community care and case management can help prevent the need for hospital admission55. However, a poor control/selfcare of the disease potentially due to the presence of mental health comorbidity may lead to an increased risk of unplanned hospitalisations and even of mortality; which could explain in part the results obtained in our study. The high prevalence of comorbidity, specifically of mental health comorbidities, and its negative impact on health outcomes, underscores the importance of promoting continuity of care and of integrated, person-centred care for T2D patients. Active monitoring for signs and symptoms of mental health comorbidities is essential, as is the identification of social circumstances that may influence care seeking, health outcomes, and the need for health services56. Our findings are of particular relevance for older populations in which the comorbidity burden is typically higher, and highlight the importance of identifying and adequately treating psychiatric comorbidities that can result in an increased risk of negative health outcomes in T2D patients.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is that it is based on a population cohort, including almost all patients with T2D of the reference population in the study area. Data of this cohort are obtained from primary sources of information such as primary care and hospital electronic health records and clinical-administrative databases. This provides a high degree of reliability regarding the diagnosis of T2D and mental health comorbidity; therefore, this information should be more accurate than if it had been self-reported by patients. Our analysis included not only highly prevalent mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, but also other psychiatric disorders less frequently studied in diabetic patients such as schizophrenia and substance use disorder.

On the other hand, one limitation inherent to the analysis of healthcare records is the potential underdiagnosis of certain conditions. We had information on all-cause mortality, but the cause of death was not available in the cohort (e.g., percentage of deaths due to suicide). We neither had the date of diagnosis of T2D or mental health comorbidity, which could bias our results regarding mortality risk by not taking into account the duration of T2D. Furthermore, the risk of mortality may have been overestimated in patients who had T2D for more prolonged periods given the higher likelihood of T2D-associated complications unrelated to the presence of mental health comorbidity.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that one in five patients with T2D suffers from mental health comorbidity and that the presence of this type of comorbidity is associated with an increased risk of mortality and hospital services use, regardless age, sex and number of other comorbidities. Particular attention should be paid to diabetic patients with substance use disorder or schizophrenia. These findings underline the need for developing global management strategies to facilitate the prevention, early detection, diagnosis and monitoring of mental health comorbidities in T2D patients. The high prevalence of multimorbidity found in T2D patients highlights the importance of providing continuity of care and person-centred approaches to improve the management and outcome of this chronic disease.

Methods

Study design, population and data source

This retrospective, observational study was conducted in the EpiChron Cohort57. This cohort includes socio-demographic, clinical, health services use and health outcomes information for all users of the public health system of the Spanish region of Aragón (1.3 million inhabitants; 98% of them are users of the public health system). The information contained in electronic health records and clinical-administrative databases is linked at the patient level and then anonymized. A description of the cohort profile, the type of data collected and data curation procedures used has been published elsewhere57.

In cohort patients, diagnoses from primary care were coded using the International Classification of Primary Care, First Version (ICPC-1), and those from hospital care were coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Diagnoses were subsequently grouped in the Expanded Diagnostic Clusters (EDCs) of the Johns Hopkins ACG System (version 11.0, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, US)58. This classification system groups clinically similar diagnostic codes, and it is useful in multimorbidity studies to count diseases when, as in this case, diagnoses from different sources and codification systems are used.

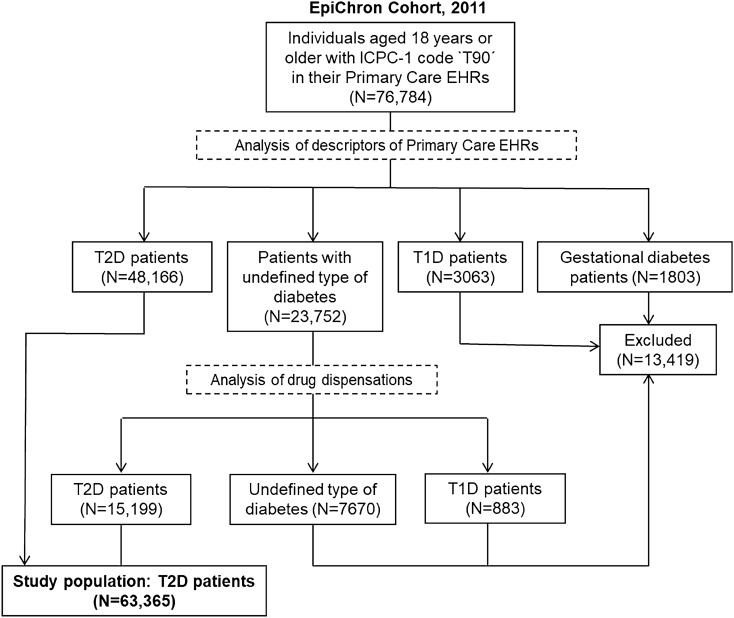

In this study, we used data corresponding to patients of the cohort aged 18 years and older who had either a diagnosis of T2D and/or a pharmaceutical dispensation for T2D treatment in 2011 (Fig. 1). To do this, we selected individuals with an ICPC-1 code ‘T90’ (Diabetes non-insulin dependent) in their primary care health records (n = 76,784). We excluded individuals with an annotation of gestational diabetes (n = 1803) or type 1 diabetes (n = 3063). For patients with unspecified type of diabetes, we selected those with no registered insulin dispensation and having at least one dispensation of sulfonylureas, glucosuric agents, glitazones, and/or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DDP-4) inhibitors (n = 15,199). We excluded from the study individuals with a specific treatment for type 1 diabetes (n = 883) and those for whom the type of diabetes could not be determined (n = 7670). Finally, this study included the information of 63,365 TD2 patients.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population. ICPC-1, International Classification of Primary Care, first version; EHRs, electronic health records; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragon (CEICA, PI18/298). The CEICA waived the requirement to obtain informed consent from patients since the information used was anonymised. All research was performed in accordance with the relevant national and international guidelines and regulations, following the Spanish law on the protection of personal data (LOPD 15/1999 of December 14).

Measurements and outcomes

We classified T2D patients in two groups: patients with no mental health comorbidity, and those with at least one mental health comorbidity defined as the presence of a primary or hospital care diagnosis of depression, anxiety, substance use disorder or schizophrenia, which were identified with EDCs ‘PSY09’, ‘PSY01’, ‘PSY02’, and ‘PSY07’, respectively. The original ICPC-1 and ICD-9 codes conforming each of these EDCs were confirmed and recorded by general practitioners and/or hospital specialists according to specific diagnostic criteria; although part of the diagnoses of mental health comorbidities was confirmed by psychiatrists, we cannot assure that all cases were confirmed or re-diagnosed by a psychiatrist. In Spain, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)59 is mostly used by both mental health specialists and general practitioners in clinical practice.

For each patient, we analysed the following explanatory variables: sex, age as of December 31, 2011, number of chronic diseases from the list of 114 EDCs defined by Salisbury et al.60, and ‘multimorbidity’, defined as the presence of at least one chronic disease in addition to T2D.

The outcome variables analysed were 4-year all-cause mortality (i.e., from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2015), and 1-year all-cause hospitalization, T2D-hospitalization, and emergency room visit (i.e., from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2012). Patients were followed until December 31, 2015, date of death, or date of withdrawal from the cohort (i.e., withdrawal from regional public health system).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the prevalence of each type of mental health comorbidity in the study population by sex and age group (i.e., 18–44, 45–64, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥ 85 years). We analysed demographic and clinical information of the study population according to the presence or not of mental health comorbidity by means or frequencies/proportions. We compared means using the Mann–Whitney U test, and proportions using the Chi-squared test.

To analyse the effect of the presence of mental health comorbidity on T2D outcomes, we used two logistic regression models and we determined the corresponding odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals, adjusted by sex, age and number of non-psychiatric comorbidities. In the first model, mental health comorbidity was included as a single variable; in the second model, each type of mental health comorbidity was included separately as different variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We conducted all statistical analyses using Stata (version 11.0, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, US).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Gobierno de Aragón [B01_20R] and the European Regional Development Fund “Construyendo Europa desde Aragón”. The authors sincerely thank Eva Giménez Labrador for her statistical support.

Author contributions

A.P.T. and M.J.F. conceived the study; I.G.F.A., B.P.P and A.G.M. conducted the statistical analyses; A.P.T., M.J.F., G.R.M., I.G.F.A. and L.A.G.F. analysed and discussed the results; I.G.F.A. and A.G.M. drafted the manuscript; I.I.S. made important contributions to the manuscript. All authors reviewed and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Inmaculada Guerrero Fernández de Alba and Antonio Gimeno-Miguel.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Maria João Forjaz and Alexandra Prados-Torres.

Contributor Information

Antonio Gimeno-Miguel, Email: agimenomi.iacs@aragon.es.

Ignatios Ioakeim-Skoufa, Email: ignacio.ioakim@hotmail.es.

References

- 1.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schabert J, Browne JL, Mosely K, Speight J. Social stigma in diabetes. PATIENT. 2013;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40271-012-0001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmet PZ. Diabetes epidemiology as a tool to trigger diabetes research and care. Diabetologia. 1999;42:499–518. doi: 10.1007/s001250051188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th ed. https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/resources/ (2020).

- 5.Alonso-Morán E, et al. Multimorbidity in people with type 2 diabetes in the Basque Country (Spain): prevalence, comorbidity clusters and comparison with other chronic patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015;26:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;142(Suppl):S8–S21. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taback SP, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Controlled trials of HbA1c measurements. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:434–435. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali S, Stone M, Skinner TC, Robertson N, Davies M, Khunti K. The association between depression and health-related quality of life in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2010;26:75–89. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cols-Sagarra C, et al. Prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes attended in primary care in Spain. Prim. Care Diabetes. 2016;10:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolau J, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlators of undiagnosed significant depressive symptoms among individuals with type 2 diabetes in a Mediterranean population. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2016;124:630–636. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-109606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimbro LB, Mangione CM, Steers WN, Duru K, McEwen L, Ettner AKSL. Depression and all-cause mortality among persons with diabetes: are older adults at higher risk? Results from the Translating Research into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013;18:1199–1216. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chima CC, Salemi JL, Wang M, Mejia de Grubb MC, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Multimorbidity is associated with increased rates of depression in patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in the United States. J. Diabetes Complic. 2017;31:1571–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun N, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults with type 2 diabetes in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012540. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders. https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/ (2017).

- 15.Gonzalez, J. Depression in The American Diabetes Association/JDRF Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook (eds. Peters, A. & Laffel, L.), 169–179 (2013).

- 16.Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:464–470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312:691–692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch CP, Gebregziabher M, Zhao Y, Hunt KJ, Egede LE. Impact of medical and psychiatric multi-morbidity on mortality in diabetes: emerging evidence. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2014;14:68. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park M, Katon WJ, Wolf FM. Depression and risk of mortality in individuals with diabetes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2013;35:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisinger Walker E, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polonsky WH, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754–760. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polonsky WH, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626–631. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrin NE, Davies MJ, Robertson N, Snoek FJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of diabetes-specific emotional distress in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2017;34:1508–1520. doi: 10.1111/dme.13448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dennick K, Sturt J, Speight J. What is diabetes distress and how can we measure it? A narrative review and conceptual model. J. Diabetes Complic. 2017;31:898–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Psychological issues and treatments for people with diabetes. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001;57:457–478. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith KJ, Deschênes SS, Schmitz N. Investigating the longitudinal association between diabetes and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2018;35:677–693. doi: 10.1111/dme.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, Davies MJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2006;23:1165–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golden SH, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299:2751–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH. Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2383–2390. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotella F, Mannucci E. Depression as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2013;74:31–37. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotella F, Mannucci E. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for depression. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013;99:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demakakos P, Zaninotto P, Nouwen A. Is the association between depressive symptoms and glucose metabolism bidirectional? Evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosom. Med. 2014;76:555–561. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nouwen A, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for the onset of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2480–2486. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1874-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu M, Zhang X, Lu F, Fang L. Depression and risk for diabetes: a meta-analysis. Can. J. Diabetes. 2015;39:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demakakos P, Muniz-Terrera G, Nouwen A. Type 2 diabetes, depressive symptoms and trajectories of cognitive decline in a national sample of community-dwellers: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farooqi A, Khunti K, Abner S, Gillies C, Morriss R, Seidu S. Comorbid depression and risk of cardiac events and cardiac mortality in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019;156:107816. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Möller-Leimkühler AM. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease and comorbid depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2007;9:71–83. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.1/ammoeller. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hazuda HP, et al. Long-term association of depression symptoms and antidepressant medication use with incident cardiovascular events in the look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) clinical trial of weight loss in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:910–918. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katon W, Maj M, Sartorius N. Depression and Diabetes. Hoboken: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sardinha A, Nardi AE. The role of anxiety in metabolic syndrome. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;7:63–71. doi: 10.1586/eem.11.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasan SS, Clavarino AM, Dingle K, Mamun AA, Kairuz T. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of depressive and anxiety disorders in australian women: a longitudinal study. J. Women’s Heal. 2015;24:889–898. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards LE, Mezuk B. Anxiety and risk of type 2 diabetes: evidence from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012;73:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016;14:006560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson RJ, et al. Anxiety and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:235–247. doi: 10.2190/KLGD-4H8D-4RYL-TWQ8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balhara YPS, Sagar R. Correlates of anxiety and depression among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;15:50. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jansson-Fröjmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008;64:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito. Resumen ejecutivo - Informe Mundial sobre las Drogas 2016; https://www.unodc.org/doc/wdr2016/WDR_2016_ExSum_spanish.pdf (2016).

- 50.Walter KN, Wagner JA, Cengiz E, Tamborlane WV, Petry NM. Substance use disorders among patients with type 2 diabetes: a dangerous but understudied combination. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2017;17:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11892-017-0832-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holt RIG. Diagnosis, epidemiology and pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus: an update for psychiatrists. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;47:S55–S63. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.47.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoffman RP. The complex inter-relationship between diabetes and schizophrenia. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2017;13:528–532. doi: 10.2174/1573399812666161201205322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brink M, Green A, Bojesen AB, Lamberti JS, Conwell Y, Andersen K. Excess medical comorbidity and mortality across the lifespan in schizophrenia: a nationwide Danish register study. Schizophr. Res. 2019;206:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mamakou V, Thanopoulou A, Gonidakis F, Tentolouris N, Kontaxakis V. Schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Psychiatrike. 2018;29:64–73. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2018.291.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to prevention quality indicators: hospital admission for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. https://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/ahrqqi/pqiguide.pdf (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001).

- 56.Muth C, et al. The Ariadne principles: how to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 2014;12:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prados-Torres A, et al. Cohort profile: the epidemiology of chronic diseases and multimorbidity. The EpiChron Cohort Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018;47:382–384. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins ACG System. https://www.hopkinsacg.org/. (2018).

- 59.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, Valderas JM, Montgomery AA. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011;61:e12–21. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X548929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]