Abstract

Dispersal is an essential process in population and community dynamics, but is difficult to measure in the field. In freshwater ecosystems, information on biological traits related to organisms’ morphology, life history and behaviour provides useful dispersal proxies, but information remains scattered or unpublished for many taxa. We compiled information on multiple dispersal-related biological traits of European aquatic macroinvertebrates in a unique resource, the DISPERSE database. DISPERSE includes nine dispersal-related traits subdivided into 39 trait categories for 480 taxa, including Annelida, Mollusca, Platyhelminthes, and Arthropoda such as Crustacea and Insecta, generally at the genus level. Information within DISPERSE can be used to address fundamental research questions in metapopulation ecology, metacommunity ecology, macroecology and evolutionary ecology. Information on dispersal proxies can be applied to improve predictions of ecological responses to global change, and to inform improvements to biomonitoring, conservation and management strategies. The diverse sources used in DISPERSE complement existing trait databases by providing new information on dispersal traits, most of which would not otherwise be accessible to the scientific community.

Subject terms: Community ecology, Freshwater ecology

| Measurement(s) | dispersal • movement quality • morphological feature • behavioral quality |

| Technology Type(s) | digital curation |

| Factor Type(s) | taxon |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Arthropoda • Mollusca • Annelida |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | aquatic biome • freshwater biome |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | Europe |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13148333

Background & Summary

Dispersal is a fundamental ecological process that affects the organization of biological diversity at multiple temporal and spatial scales1,2. Dispersal strongly influences metapopulation and metacommunity dynamics through the movement of individuals and species, respectively3. A better understanding of dispersal processes can inform biodiversity management practices4,5. However, dispersal is difficult to measure directly, particularly for small organisms, including most invertebrates6. Typically, dispersal is measured for single species7,8 or combinations of few species within one taxonomic group9–11 using methods based on mark and recapture, stable isotopes, or population genetics5,12. Such methods can directly assess dispersal events but are expensive, time-consuming, and thus impractical for studies conducted at the community level or at large spatial scales. In this context, taxon-specific biological traits represent a cost-effective alternative that may serve as proxies for dispersal5,6,13,14. These traits interact with landscape structure to determine patterns of effective dispersal15,16.

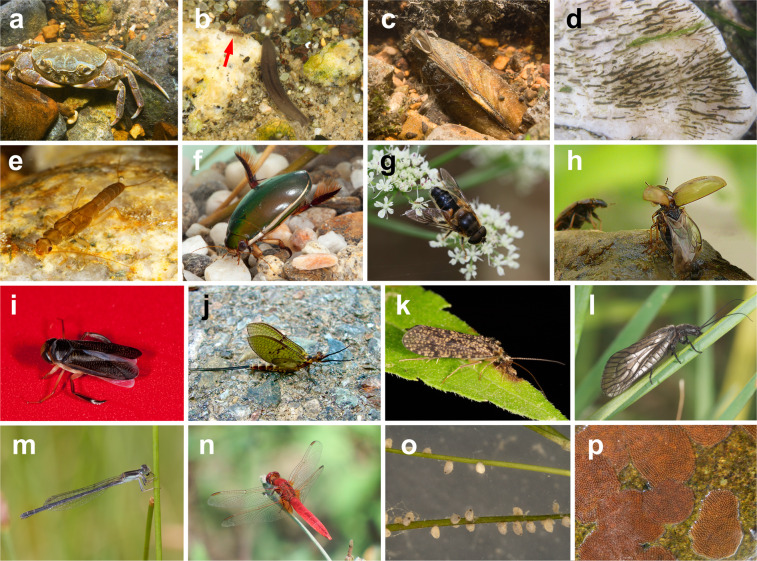

Aquatic macroinvertebrates inhabiting freshwater ecosystems include taxa with diverse dispersal modes and abilities (Fig. 1). For species with complex life cycles, such as some insects, this diversity is enhanced by life stages with different dispersal strategies. For example, aquatic juveniles of many insects disperse actively and/or passively in water whereas adults fly over land17. In all cases, dispersal is affected by multiple traits relating to the morphology6,12, life history and behaviour2 of different life stages.

Fig. 1.

The dispersal-related trait diversity of aquatic macroinvertebrates. Taxa that disperse in water include the crustacean genera Potamon (a) and Asellus (arrow in b), planarians (b), the bivalve mollusc genus Unio (c), insect larvae such as the Diptera genus Simulium (d) and Plecoptera genus Leuctra (e), and adult Coleoptera including the dytiscid genus Cybister (f). Such aquatic dispersers may move passively in the drift (c,d) and/or actively crawl or swim (a,b,e,f). Most adult insects have wings and can fly overland (f–n). Wings are morphologically diverse and include various types: one wing pair, as in Diptera such as the syrphid genus Eristalis (g); one pair of wings with elytra for Coleoptera including the genus Enochrus (h) or with hemielytra for Heteroptera such as the genus Hesperocorixa (i); two wing pairs including one pair of small hind wings for Ephemeroptera including the genus Ephemera (j); and two pairs of similar-sized wings for the Trichoptera genus Polycentropus (k), the Megaloptera genus Sialis (i) and the Odonata genera Ischnura (m) and Crocothemis (n). Wings range in size from a few mm in some Diptera (g) up to more than 3 cm (l–n), with the Odonata exemplifying the large morphologies. Taxa vary in the number of eggs produced per female, ranging from tens per reproductive cycle for most Coleoptera and Heteroptera such as the genus Sigara (o) to several hundreds in the egg masses of most Ephemeroptera and Trichoptera, such as those of the genus Hydropsyche (p). Credits: Adolfo Cordero-Rivera (a–g,i,k–n), Jesús Arribas (h), Pere Bonada (j), José Antonio Carbonell (o) and Maria Alp (p).

We compiled and the harmonized information on dispersal-related traits of freshwater macroinvertebrates from across Europe, including both aquatic and aerial (i.e. flying) stages. Although information on some dispersal-related traits such as body size, reproduction, locomotion and dispersal mode is available in online databases for European18–20 and North American taxa21, other relevant information is scattered across published literature and unpublished data. Informed by the input of 19 experts, we built a comprehensive database containing nine dispersal-related traits subdivided into 39 trait categories for 480 European taxa. Dispersal-related traits were selected and their trait categories fuzzy-coded22 following an approach comparable to that used to develop existing databases23. Our aim was to provide a single resource facilitating the incorporation of dispersal into ecological research, and to create the basis for a global dispersal database.

Methods

Dispersal-related trait selection criteria

We defined dispersal as the unidirectional movement of individuals from one location to another1, assuming that population-level dispersal rates depend on both the number of dispersing propagules and dispersers’ ability to move across a landscape11,24.

We selected nine dispersal-related morphological, behavioural and life-history traits (Online-only Table 1). Selected morphological traits were maximum body size, female wing length and wing pair type, the latter two relating only to flying adult insects. Maximum body size influences organisms’ dispersal6, especially for active dispersers25, with larger animals more capable of active dispersal over longer distances (e.g. flying adult dragonflies6, Fig. 1). Wing morphology, and in particular wing length, is related to the dispersal of flying adult insects6,26. Female wing length was selected because females connect and sustain populations through oviposition, thus representing adult insects’ colonization capacity27. Females with larger wings are likely to oviposit farther from their source population6,10,28. We also described insect wing morphology as wing pair types, i.e. one or two pairs of wings, and the presence of halters, elytra or hemielytra, or small hind wings12 (Fig. 1). Selected life-history traits were adult life span, life-cycle duration, annual number of reproductive cycles and lifelong fecundity. Adult life span and life-cycle duration respectively reflect the adult (i.e. reproductive) and total life duration, with longer-lived animals typically having more dispersal opportunities13. The annual number of reproductive cycles and lifelong fecundity assess dispersal capacity based on potential propagule production, with multiple reproductive cycles and abundant eggs typically increasing the number of dispersal events6. Dispersal behaviour was represented by a taxon’s predominant dispersal mode (passive and/or active, aquatic and/or aerial), and by its propensity to drift, which indicates the frequency of flow-mediated passive downstream dispersal events.

Table 1.

Dispersal-related aquatic macroinvertebrate traits included in the DISPERSE database.

| Trait | Categories |

|---|---|

| Maximum body size (cm) | <0.25 |

| ≥0.25–0.5 | |

| ≥0.5–1 | |

| ≥1–2 | |

| ≥2–4 | |

| ≥4–8 | |

| ≥8 | |

| Female wing length (insects only) (mm) | <5 |

| ≥5–10 | |

| ≥10–15 | |

| ≥15–20 | |

| ≥20–30 | |

| ≥30–40 | |

| ≥40–50 | |

| ≥50 | |

| Wing pair type (insects only) | 1 pair + halters |

| 1 pair + elytra or hemielytra | |

| 1 pair + small hind wings | |

| 2 similar-sized pairs | |

| Life-cycle duration | ≤1 year |

| >1 year | |

| Adult life span | <1 week |

| ≥1 week–1 month | |

| ≥1 month–1 year | |

| ≥1 year | |

| Lifelong fecundity (number of eggs per female) | <100 |

| ≥100–1000 | |

| ≥1000–3000 | |

| ≥3000 | |

| Potential number of reproductive cycles per year | <1 |

| 1 | |

| >1 | |

| Dispersal strategy | Aquatic active |

| Aquatic passive | |

| Aerial active | |

| Aerial passive | |

| Propensity to drift | Rare/catastrophic |

| Occasional | |

| Frequent |

Data acquisition and compilation

A taxa list was generated based on the taxonomies used in existing European aquatic invertebrate databases18,20. Trait information was sourced primarily from the literature using Google Scholar searches of keywords including trait names, synonyms and taxon names (Supplementary File 1, Table S1), and by searching in existing databases18,21. Altogether, >300 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters were consulted. When no European studies were available, we considered information from other continents only if experts considered traits as comparable across regions. When published information was lacking, traits were coded based on authors’ expert knowledge and direct measurements. Specifically, for 139 species in 69 genera of Coleoptera and Heteroptera, female wing lengths were characterized using measurements of 538 individuals in experts’ reference collections, comprising organisms sampled in Finland, Greece and Hungary. The number of species measured within a genus varied between 1 and 10 in relation to the number of European species within each genus. For example, for the most species-rich genera, both common and rare species from northern and southern latitudes were included.

Fuzzy-coding approach and taxonomic resolution

Traits were coded using a ‘fuzzy’ approach, in which a value given to each trait category indicates if the taxon has no (0), weak (1), moderate (2) or strong (3) affinity with the category22. Affinities were determined based on the proportion of observations (i.e. taxon-specific information from the literature or measurements) or expert opinions that fell within each category for each trait29. Fuzzy coding can incorporate intra-taxon variability when trait profiles differ among e.g. species within a genus, early and late instars of one species, or individuals of one species in different environments29. Most traits were coded at genus level, but some Diptera and Annelida were coded at family, sub-family or tribe level because of their complex taxonomy, identification difficulties and the scarcity of reliable information about their traits.

Data Records

DISPERSE can be downloaded as an Excel spreadsheet from the Intermittent River Biodiversity Analysis and Synthesis (IRBAS) webpage (irbas.inrae.fr) and the data repository Figshare30.

The database comprises three sheets: DataKey, Data and Reference list. The “Datakey” sheet summarizes the content of each column in the “Data” sheet. The “Data” sheet includes the fuzzy-coded trait categories and cites the sources used to code each trait. The first six columns list the taxa and their taxonomy (group; family; tribe/sub-family or genus [depending on the level coded]; genus synonyms; lowest taxonomic resolution achieved) to allow users to sort and compile information. Sources are cited in chronological order by the surname of the first author and the year of publication. Expert evaluations are reported as “Unpublished” followed by the name of the expert providing the information. Direct measurements are reported as “Direct measurement from” followed by the expert’s name. The “Reference list” sheet contains the references cited in the “Data” sheet, organized in alphabetical order and then by date.

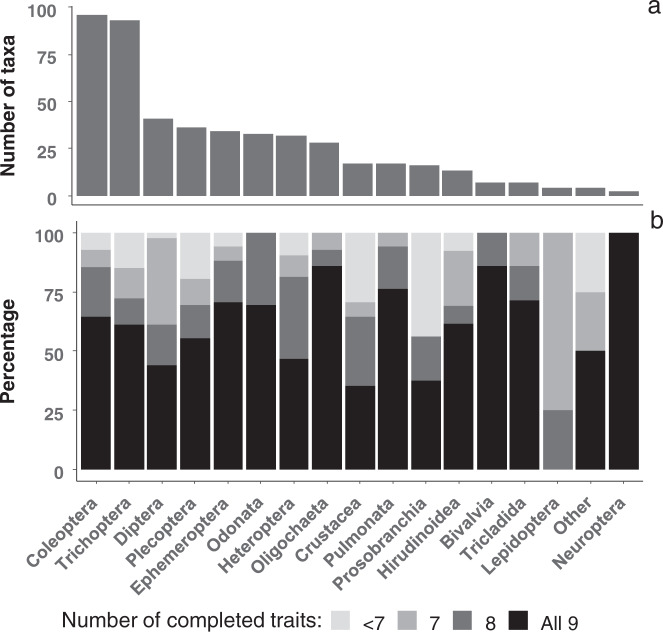

In total, the database contains nine dispersal-related traits divided into 39 trait categories for 480 taxa. Most (78%) taxa are insects, principally Coleoptera and Trichoptera, as these are, together with Diptera, the most diverse orders in freshwater ecosystems31. DISPERSE provides complete trait information for 61% of taxa, with 1–2 traits being incomplete for the 39% remaining taxa (Table 2, Fig. 2). The traits with the highest percentage of information across taxa were wing pair type and maximum body size, followed by dispersal strategy, life-cycle duration, potential number of reproductive cycles per year, and female wing length (Table 2). The percentage of completed information was lower for two life-history traits: adult life span and lifelong fecundity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of taxa completed and relative contribution of different sources of information (i.e. literature, expert knowledge, direct measurement) used to build the DISPERSE database.

| Trait | Taxa completed (%) | Source of information (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | Expert | Measured | ||

| Maximum body size | 99 | 100 | ||

| Female wing length | 95 | 57 | 12 | 31 |

| Wing pair type | 100 | 100 | ||

| Life-cycle duration | 98 | 100 | ||

| Adult life span | 79 | 65 | 35 | |

| Lifelong fecundity | 75 | 77 | 23 | |

| Potential number of reproductive cycles per year | 98 | 100 | ||

| Dispersal strategy | 98 | 100 | ||

| Propensity to drift | 80 | 90 | 10 | |

| All traits | 61 | 88 | 9 | 3 |

Fig. 2.

Total number of taxa and percentage of the nine traits completed in each insect order and macroinvertebrate phylum, sub-phylum, class or sub-class. “Other” includes Hydrozoa, Hymenoptera, Megaloptera and Porifera, for which the database includes only one genus each.

Technical Validation

Most of the trait information (88%) originated from published literature (Supplementary File 1) and the remaining traits were coded based on expert knowledge (9%) and direct measurements (3%) (Table 2). The database states information sources for each trait and taxon, allowing users to evaluate data quality. Most traits were coded using multiple sources representing multiple species within a genus. When only one study was available, we supplemented this information with expert knowledge, to ensure that trait codes represented potential variability in the taxon.

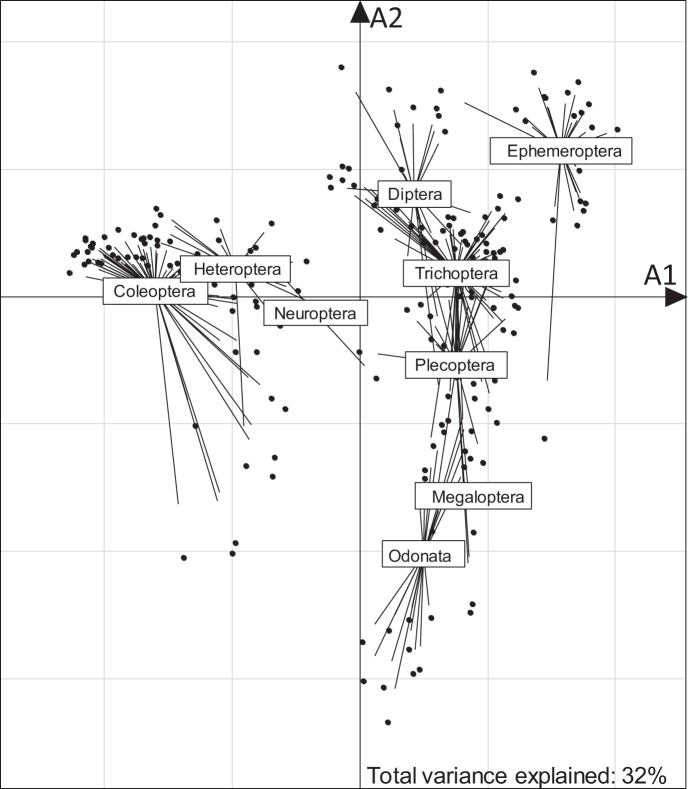

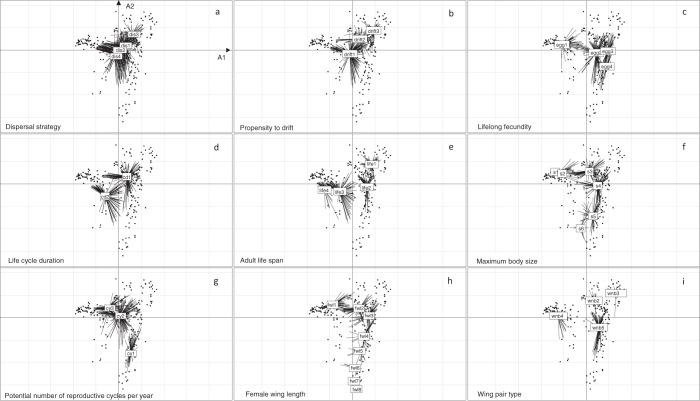

Using insects as an example, we performed a fuzzy correspondence analysis (FCA)22 to visualize variability in trait composition among taxa (Fig. 3). Insect orders were clearly distinguished based on their dispersal-related traits, with 32% of the variation explained by the first two FCA axes. Wing pair type and lifelong fecundity had the highest correlation with axis A1 (coefficient 0.87 and 0.63, respectively). Female wing length (0.73) and maximum body size (0.55) were most strongly correlated with axis A2 (Fig. 3 and 4). For example, female Coleoptera typically produce few eggs and have intermediate maximum body sizes and wing lengths, Odonata produce an intermediate number of eggs and have long wings, and Ephemeroptera produce many eggs and have short wings (Fig. 1 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Variability in the dispersal-related trait composition of all insect orders with complete trait profiles along fuzzy correspondence analysis axes A1 and A2. Dots indicate taxa and lines converge to the centroid of each order to depict within-group dispersion.

Fig. 4.

Trait category locations in the fuzzy correspondence analysis ordination space for each trait of all insect orders with complete trait profiles: (a) Dispersal strategy = dis1: aquatic passive, dis2: aquatic active, dis3: aerial passive, dis4: aerial active; (b) Propensity to drift = drift1: rare/catastrophic, drift2: occasional, drift3: frequent; (c) Fecundity = egg1: < 100 eggs, egg2: ≥ 100–1000 eggs, egg3: 1000–3000 eggs, egg4: ≥ 3000 eggs; (d) Life-cycle duration = cd1: ≤ 1 year, cd2: > 1 year; (e) Adult life span = life1: < 1 week, life2: ≥ 1 week – 1 month, life3: ≥ 1 month – 1 year, life4: > 1 year; (f) Maximum body size (cm) = s1: < 0.25, s2: ≥ 0.25–0.5, s3: ≥ 0.5–1, s4: ≥ 1–2; s5: ≥ 2–4, s6: ≥ 4–8; (g) Potential number of reproductive cycles per year = cy1: < 1, cy2: 1, cy3: > 1; (h) Female wing length (mm) = fwl1: < 5, fwl2: ≥ 5–10, fwl3: ≥ 10–15, fwl4: ≥ 15–20, fwl5: ≥ 20–30, fwl6: ≥ 30–40, fwl7: ≥ 40–50, fwl8: ≥ 50; (i) Wing pair type = wnb2: 1 pair + halters, wnb3: 1 pair + 1 pair of small hind wings, wnb4: 1 pair + 1 pair of elytra or hemielytra, wnb5: 2 similar-sized pairs.

The database currently represents a Europe-wide resource which can be updated and expanded as new information becomes available, to include more taxa and traits from across and beyond Europe. For example, additional information could be collected on other measures of wing morphology10,14 and functionality or descriptors of exogenous dispersal vectors such as wind and animals32. New data can be contributed by contacting the corresponding author or by completing the contact form on the IRBAS website (http://irbas.inrae.fr/contact), and the online database will be updated accordingly. DISPERSE lays the foundations for a global dispersal trait database, the lack of which is recognized as limiting research progress across multiple disciplines33.

Usage Notes

DISPERSE is the first publicly available database describing the dispersal traits of aquatic macroinvertebrates and includes information on both aquatic and aerial (i.e. flying) life stages. It provides good coverage of macroinvertebrates at the genus level, which is generally considered as sufficient to capture biodiversity dynamics34–37. It will promote incorporation of dispersal proxies into fundamental and applied population and community ecology in freshwater ecosystems5. In particular, metacommunity ecology may benefit from the use of dispersal traits15,38, which enable classification of taxa according to their dispersal potential in greater detail. Such classification, used in combination with, for example, spatial distance measurements39,40, could advance our understanding of the effects of regional dispersal processes on community assembly and biodiversity patterns. Improved knowledge of taxon-specific dispersal abilities may also inform the design of more effective management practices. For example, recognizing dispersal abilities in biomonitoring methods could inform enhancements to catchment-scale management strategies that support ecosystems adapting to global change41,42. DISPERSE could also inform conservation strategies by establishing different priorities depending on organisms’ dispersal capacities in relation to spatial connectivity43.

DISPERSE could also improve species distribution models (SDMs), in which dispersal has rarely been considered due to insufficient data13, limiting the accuracy of model predictions44,45. Recent trait-based approaches have begun to integrate dispersal into SDMs45, and information from DISPERSE could increase model accuracy46,47. Including dispersal in SDMs is especially relevant to assessments of biodiversity loss and species vulnerability to climate change46,48,49. DISPERSE could also advance understanding of eco-evolutionary relationships and biogeographical phenomena. In an evolutionary context, groups with lower dispersal abilities should be genetically and taxonomically richer due to long-term isolation50,51. From a biogeographical perspective, regions affected by glaciations should have species with greater dispersal abilities, enabling postglacial recolonization52.

By capturing different dispersal-related biological traits, DISPERSE provides information on organisms’ potential ability to move between localities as well as on reproduction and recruitment15. Traits also facilitate comparison of taxa with different dispersal strategies, which could inform studies conducted at large spatial scales, independent of taxonomy53.

Users should note that the dispersal-related traits included in DISPERSE represent an indirect measure of dispersal, not effective dispersal. Therefore, the database is not intended to substitute population-level studies related to dispersal, but to act as a repository that collates and summarizes information from such studies. As freshwater biodiversity declines at unprecedented rates54,55, collecting, harmonizing and sharing dispersal-related data on freshwater organisms will underpin evidence-informed initiatives that seek to support the resilience of ecosystems adapting to global change.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the COST Action CA15113 Science and Management of Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams (http://www.smires.eu), funded by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). NC was supported by the French research program Make Our Planet Great Again. MC-A was supported by the MECODISPER project (CTM2017-89295-P) funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (MINECO) - Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). AC-R acknowledges funding by MINECO-AEI-ERDF (CGL2014-53140-P). CG-C was supported by the EDRF (COMPETE2020 and PT2020) and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, through the CBMA strategic program UID/BIA/04050/2019 (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007569) and the STREAMECO project (Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning under climate change: from the gene to the stream, PTDC/CTA-AMB/31245/2017). JH was supported by the project ‘Global taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity of stream macroinvertebrate communities: unravelling spatial trends, ecological determinants and anthropogenic threats’ funded by the Academy of Finland. PP and MP were supported by the Czech Science Foundation (P505-20-17305S). ZC was supported by the projects EFOP-3.6.1.-16-2016-00004, 20765-3/2018/FEKUTSTRAT and TUDFO/47138/2019-ITM. We thank two anonymous reviewers for insightful feedback that improved an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

N.B., N.C. and R.Sa. developed the idea and data collection framework. R.Sa. compiled most of the dispersal-related trait data and structured the database. All authors contributed to the addition and checking of information included in the database, and Z.C. provided direct measurements of several taxa. A.C.-R. designed Fig. 1. M.A., M.C.-A., C.G.-C. and M.F. helped to finalize the database reference list. N.C. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to its finalization. R.St. proofread the manuscript.

Code availability

Analyses were conducted and figures were produced using the R environment56including the package ade457. Scripts are available at Figshare30.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Romain Sarremejane, Núria Cid.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-020-00732-7.

References

- 1.Bohonak AJ, Jenkins DG. Ecological and evolutionary significance of dispersal by freshwater invertebrates. Ecol. Lett. 2003;6:783–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clobert, J., Baguette, M., Benton, T. G. & Bullock, J. M. Dispersal Ecology and Evolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

- 3.Heino J, et al. Metacommunity organisation, spatial extent and dispersal in aquatic systems: Patterns, processes and prospects. Freshw. Biol. 2015;60:845–869. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton PS, et al. Guidelines for using movement science to inform biodiversity policy. Environ. Manage. 2015;56:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00267-015-0570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heino J, et al. Integrating dispersal proxies in ecological and environmental research in the freshwater realm. Environ. Rev. 2017;25:334–349. doi: 10.1139/er-2016-0110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rundle, S. D., Bilton, D. T. & Foggo, A. in Body Size: The Structure and Function of Aquatic Ecosystems (eds. Hildrew, A. G., Raffaelli, D. G. & Edmonds-Brown, R.) 186–209 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007).

- 7.Macneale KH, Peckarsky BL, Likens GE. Stable isotopes identify dispersal patterns of stonefly populations living along stream corridors. Freshw. Biol. 2005;50:1117–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2005.01387.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troast D, Suhling F, Jinguji H, Sahlén G, Ware J. A global population genetic study of Pantala flavescens. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French SK, McCauley SJ. The movement responses of three libellulid dragonfly species to open and closed landscape cover. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2019;12:437–447. doi: 10.1111/icad.12355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arribas P, et al. Dispersal ability rather than ecological tolerance drives differences in range size between lentic and lotic water beetles (Coleoptera: Hydrophilidae) J. Biogeogr. 2012;39:984–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02641.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lancaster J, Downes BJ. Dispersal traits may reflect dispersal distances, but dispersers may not connect populations demographically. Oecologia. 2017;184:171–182. doi: 10.1007/s00442-017-3856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancaster, J. & Downes, B. J. Aquatic Entomology (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

- 13.Stevens VM, et al. Dispersal syndromes and the use of life-histories to predict dispersal. Evol. Appl. 2013;6:630–642. doi: 10.1111/eva.12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Outomuro D, Johansson F. Wing morphology and migration status, but not body size, habitat or Rapoport’s rule predict range size in North-American dragonflies (Odonata: Libellulidae) Ecography. 2019;42:309–320. doi: 10.1111/ecog.03757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonkin JD, et al. The role of dispersal in river network metacommunities: patterns, processes, and pathways. Freshw. Biol. 2018;63:141–163. doi: 10.1111/fwb.13037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown BL, Swan CM. Dendritic network structure constrains metacommunity properties in riverine ecosystems. J. Anim. Ecol. 2010;79:571–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wikelski M, et al. Simple rules guide dragonfly migration. Biol. Lett. 2006;2:325–329. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt-Kloiber A, Hering D. An online tool that unifies, standardises and codifies more than 20,000 European freshwater organisms and their ecological preferences. Ecol. Indic. 2015;53:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serra SRQ, Cobo F, Graça MAS, Dolédec S, Feio MJ. Synthesising the trait information of European Chironomidae (Insecta: Diptera): towards a new database. Ecol. Indic. 2016;61:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tachet, H., Richoux, P., Bournaud, M. & Usseglio-Polatera, P. Invertébrés d’Eau Douce: Systématique, Biologie, Écologie (CNRS Éditions, 2010).

- 21.Vieira, N. K. M. et al. A Database of Lotic Invertebrate Traits for North America (U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 187, 2006).

- 22.Chevenet F, Dolédec S, Chessel D. A fuzzy coding approach for the analysis of long-term ecological data. Freshw. Biol. 1994;31:295–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1994.tb01742.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmera D, Podani J, Heino J, Erös T, Poff NLR. A proposed unified terminology of species traits in stream ecology. Freshw. Sci. 2015;34:823–830. doi: 10.1086/681623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancaster J, Downes BJ, Arnold A. Lasting effects of maternal behaviour on the distribution of a dispersive stream insect. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011;80:1061–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins DG, et al. Does size matter for dispersal distance? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007;16:415–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00312.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison RG. Dispersal polymorphisms in insects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1980;11:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham ES, Storey R, Smith B. Dispersal distances of aquatic insects: upstream crawling by benthic EPT larvae and flight of adult Trichoptera along valley floors. New Zeal. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2017;51:146–164. doi: 10.1080/00288330.2016.1268175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffsten PO. Site-occupancy in relation to flight-morphology in caddisflies. Freshw. Biol. 2004;49:810–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2004.01229.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonada N, Dolédec S. Does the Tachet trait database report voltinism variability of aquatic insects between Mediterranean and Scandinavian regions? Aquat. Sci. 2018;80:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00027-017-0554-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarremejane R, 2020. DISPERSE, a trait database to assess the dispersal potential of aquatic macroinvertebrates. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lévêque C, Balian EV, Martens K. An assessment of animal species diversity in continental waters. Hydrobiologia. 2005;542:39–67. doi: 10.1007/s10750-004-5522-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green AJ, Figuerola J. Recent advances in the study of long-distance dispersal of aquatic invertebrates via birds. Divers. Distrib. 2005;11:149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1366-9516.2005.00147.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maasri A. A global and unified trait database for aquatic macroinvertebrates: the missing piece in a global approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019;7:1–3. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2019.00065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cañedo-Argüelles M, et al. Dispersal strength determines meta-community structure in a dendritic riverine network. J. Biogeogr. 2015;42:778–790. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Datry T, et al. Metacommunity patterns across three Neotropical catchments with varying environmental harshness. Freshw. Biol. 2016;61:277–292. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swan CM, Brown BL. Metacommunity theory meets restoration: isolation may mediate how ecological communities respond to stream restoration. Ecol. Appl. 2017;27:2209–2219. doi: 10.1002/eap.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarremejane R, Mykrä H, Bonada N, Aroviita J, Muotka T. Habitat connectivity and dispersal ability drive the assembly mechanisms of macroinvertebrate communities in river networks. Freshw. Biol. 2017;62:1073–1082. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson B, Peres-Neto PR. Quantifying and disentangling dispersal in metacommunities: How close have we come? How far is there to go? Landsc. Ecol. 2010;25:495–507. doi: 10.1007/s10980-009-9442-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarremejane R, et al. Do metacommunities vary through time? Intermittent rivers as model systems. J. Biogeogr. 2017;44:2752–2763. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Datry T, Moya N, Zubieta J, Oberdorff T. Determinants of local and regional communities in intermittent and perennial headwaters of the Bolivian Amazon. Freshw. Biol. 2016;61:1335–1349. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cid N, et al. A metacommunity approach to improve biological assessments in highly dynamic freshwater ecosystems. Bioscience. 2020;70:427–438. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Datry T, Bonada N, Heino J. Towards understanding the organisation of metacommunities in highly dynamic ecological systems. Oikos. 2016;125:149–159. doi: 10.1111/oik.02922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hermoso V, Cattarino L, Kennard MJ, Watts M, Linke S. Catchment zoning for freshwater conservation: refining plans to enhance action on the ground. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015;52:940–949. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thuiller W, et al. A road map for integrating eco-evolutionary processes into biodiversity models. Ecol. Lett. 2013;16:94–105. doi: 10.1111/ele.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendes P, Velazco SJE, de Andrade AFA, De Marco P. Dealing with overprediction in species distribution models: How adding distance constraints can improve model accuracy. Ecol. Model. 2020;431:109180. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2020.109180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willis SG, et al. Integrating climate change vulnerability assessments from species distribution models and trait-based approaches. Biol. Conserv. 2015;190:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper JC, Soberón J. Creating individual accessible area hypotheses improves stacked species distribution model performance. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018;27:156–165. doi: 10.1111/geb.12678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markovic D, et al. Europe’s freshwater biodiversity under climate change: distribution shifts and conservation needs. Divers. Distrib. 2014;20:1097–1107. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bush A, Hoskins AJ. Does dispersal capacity matter for freshwater biodiversity under climate change? Freshw. Biol. 2017;62:382–396. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bohonak AJ. Dispersal, gene flow, and population structure. Q. Rev. Biol. 1999;74:21–45. doi: 10.1086/392950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dijkstra K-DB, Monaghan MT, Pauls SU. Freshwater biodiversity and aquatic insect diversification. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014;59:143–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-161958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Múrria C, et al. Local environment rather than past climate determines community composition of mountain stream macroinvertebrates across Europe. Mol. Ecol. 2017;26:6085–6099. doi: 10.1111/mec.14346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Statzner B, Bêche LA. Can biological invertebrate traits resolve effects of multiple stressors on running water ecosystems? Freshw. Biol. 2010;55:80–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02369.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strayer DL, Dudgeon D. Freshwater biodiversity conservation: recent progress and future challenges. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 2010;29:344–358. doi: 10.1899/08-171.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reid AJ, et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2019;94:849–873. doi: 10.1111/brv.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2020).

- 57.Dray S, Dufour A-B. The ade4 package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007;1:1–20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Sarremejane R, 2020. DISPERSE, a trait database to assess the dispersal potential of aquatic macroinvertebrates. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Analyses were conducted and figures were produced using the R environment56including the package ade457. Scripts are available at Figshare30.