Summary

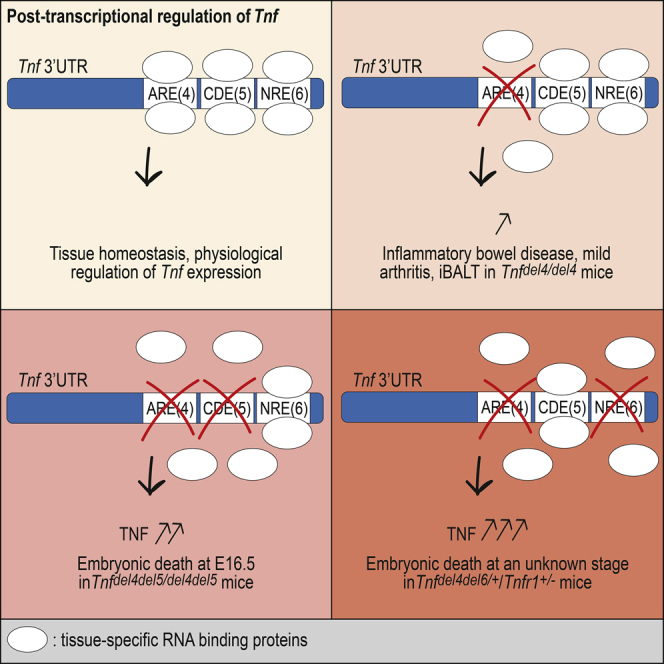

Post-transcriptional regulation mechanisms control mRNA stability or translational efficiency via ribosomes, and recent evidence indicates that it is a major determinant of the accurate levels of cytokine mRNAs. Transcriptional regulation of Tnf has been well studied and found to be important for the rapid induction of Tnf mRNA and regulation of the acute phase of inflammation, whereas study of its post-transcriptional regulation has been largely limited to the role of the AU-rich element (ARE), and to a lesser extent, to that of the constitutive decay element (CDE). We have identified another regulatory element (NRE) in the 3′ UTR of Tnf and demonstrate that ARE, CDE, and NRE cooperate in vivo to efficiently downregulate Tnf expression and prevent autoimmune inflammatory diseases. We also show that excessive TNF may lead to embryonic death.

Subject Areas: Molecular Biology, Immunology, Developmental Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Three regions of Tnf 3′ UTR cooperate to regulate Tnf expression post-transcriptionally

-

•

Dysregulation of Tnf post-transcriptional regulation causes inflammatory diseases

-

•

Strong overexpression of TNF leads to vascular failure and embryonic lethality

Molecular Biology; Immunology ; Developmental Biology

Introduction

The role of excessive TNF in multiple inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been largely documented over the past 25 years, and the development of anti-TNF therapies has been a milestone in the treatment of RA and many other inflammatory conditions. Adalimumab, an anti-TNF biologic used to treat RA, has been the best-selling drug worldwide for several years. Many signals have been described that may lead to the increase of TNF expression through the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB (Liu et al., 2017). Although the importance of Tnf mRNA 3′ UTR in post-transcriptional regulation has been recognized early (Han and Beutler, 1990), the mechanisms that regulate Tnf expression post-transcriptionally in vivo have been much less studied, with the notable exception of the action of tristetraprolin (TTP) (ZFP36/TTP) on the adenylate-uridylate-rich element (AU-rich element [ARE]) found in Tnf 3′ UTR. The ARE is a conserved sequence made of several UAUUUAU motifs that was first discovered in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNA and shown to target this RNA for rapid degradation (Shaw and Kamen, 1986). AREs are present in the 3′ UTRs of many cytokines including TNF, interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6 as well as in the mRNAs of factors regulating the cell cycle (Galloway and Turner, 2017). To date, around 20 ARE-binding proteins (ARE-BPs) have been identified. Their effects on mRNA turnover are varied, and they may promote the degradation of transcripts or their stabilization (Otsuka et al., 2019). TTP, a well characterized ARE-BP, plays an important role in Tnf post-transcriptional regulation. TTP-deficient mice display a complex inflammatory phenotype that includes arthritis, cachexia, and autoimmunity (Taylor et al., 1996). Treatment of young TTP-deficient mice with antibodies to TNF prevented the development of essentially all aspects of the phenotype. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that binding of TTP to the Tnf ARE mediates deadenylation and destabilization of Tnf mRNA (Lai et al., 2000).

The role of the ARE in the regulation of Tnf expression in vivo was demonstrated 20 years ago when mice with a deletion of the ARE from the Tnf gene (TNFΔARE) were shown to develop severe arthritis and IBD (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999).

A constitutive decay element (CDE) was also identified in Tnf 3′ UTR (Stoecklin et al., 2003). Following the observation that a reporter transcript harboring full-length Tnf 3′ UTR remained susceptible to decay in cells possessing defective ARE-dependent decay machinery, the CDE was identified as a 15-nt conserved sequence acting independently from the ARE in a constitutive manner. The CDE forms a stem-loop motif recognized by Roquin-1, which, similar to the binding of TTP to the ARE, is reported to recruit the Ccr4-Not complex to mediate mRNA decay (Leppek et al., 2013). Although the mechanisms of CDE-mediated mRNA decay have been described, the relevance of the CDE in the regulation of Tnf in vivo has not yet been established.

We recently described BPSM1 mice, a spontaneous mutant mouse in which the insertion of a retrotransposon eliminates most of the 3′ UTR of Tnf, causing elevated levels of the cytokine and the development of RA and heart valve disease (HVD) in these mice (Lacey et al., 2015). We also identified a previously unrecognized regulatory element in Tnf 3′ UTR, which we called the New Regulatory Element (NRE). We now have further dissected the 3′ UTR of Tnf and show that the ARE, CDE, and NRE cooperate to efficiently regulate the amount of Tnf mRNA present in a given cell at a given time. To further evaluate the importance of the 3′ UTR in the regulation of TNF levels in vivo, we generated mice with deletions of one or two regulatory elements in Tnf 3′ UTR and show that the phenotypes associated with these deletions vary enormously in severity, two of them even causing embryonic death.

Results

Three Major Regulatory Elements in Tnf 3′ UTR

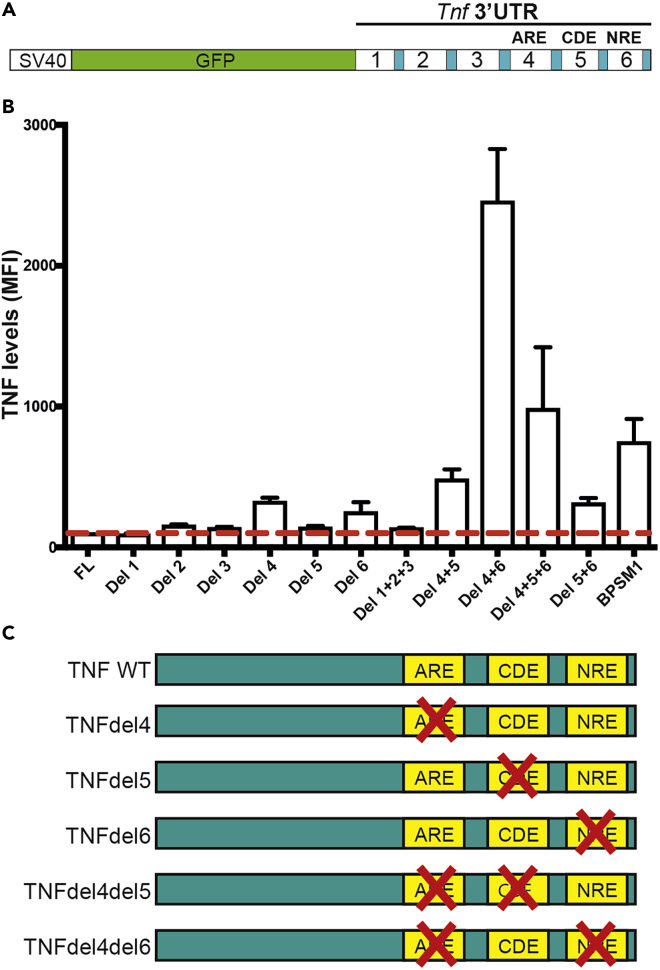

We previously used transient transfection and a series of GFP reporters derived from the pGL3-promoter reporter (Promega) to investigate the potential interaction of members of the CCCH family of zinc finger-containing proteins (ZFP) with several engineered variants of Tnf 3′ UTR (Lacey et al., 2015). This led to the identification of a regulatory element, the NRE, located at the distal end of Tnf 3′ UTR, just before the polyadenylation signal. To further investigate potential interactions between the different regions (regions 1–6, Figure 1A) previously defined, we have generated additional reporter constructs with deletions of multiple regions within Tnf 3′ UTR and performed transient transfection experiments in HEK293 cells. All constructs were compared to a reporter containing the wild-type (WT) 3′ UTR of mouse Tnf (Figure 1B). Deletion of region 1, 2, 3, or 5 alone had no significant impact on the level of expression of GFP, whereas deletion of region 4 or 6 led to a 3-fold and 2.5-fold increase in GFP expression, respectively. Deletion of regions 1, 2, and 3 together did not lead to a change in reporter activity, suggesting that these three regions do not contain any motif of significance regarding post-transcriptional regulation of Tnf expression, at least in the context of these experiments. Deletion of regions 4 and 5 together led to a 5-fold increase in reporter activity, suggesting that regions 4 and 5 somehow cooperate to downregulate Tnf expression. Deletion of regions 4 and 6 together led to a 25-fold increase in GFP expression, indicating the crucial role of these two regions in the downregulation of Tnf expression. Surprisingly, deletion of regions 4, 5, and 6 together only led to a 10-fold increase in GFP reporter expression, and a construct harboring the Tnf 3′ UTR found in the BPSM1 mice (lacking regions 2–6 replaced by a retrotransposon) reported a 7.5-fold increase in GFP.

Figure 1.

Several Elements within Tnf 3′ UTR Cooperate to Regulate its Expression Post-transcriptionally

(A) Schematic representation of the GFP reporter constructs used to assay the effect of the deletion of particular regions of mouse Tnf 3′ UTR.

(B) Deletion of regions 4, 5, 6, or combinations of those greatly affect the expression of the GFP reporter relative to the full-length (FL) Tnf 3′ UTR in HEK293 cells. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(C) Schematic representation of the Tnf 3′ UTR mutations that were engineered in mice using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

See also Figure S1.

Together, these results suggest that the most important elements controlling post-transcriptional regulation of Tnf expression reside in regions 4, 5, and 6 of the 3′ UTR. While all the results concerning regions 4 and 6 suggest that these elements are bound by repressors of Tnf expression, the results obtained with the construct lacking regions 4 and 5 and the construct lacking regions 4, 5, and 6 suggest that region 5 might have a dual role in the regulation of Tnf expression. Region 5 contains the CDE, a 17-nt hairpin loop that is bound by Rc3h1 and Rc3h2 (also known as Roquin-1 and -2) (Leppek et al., 2013; Mino et al., 2015). Rc3h1 was described as crucial for the limitation of TNF-α production in resting and activated macrophages (Leppek et al., 2013). As our region 5 covers more than the CDE itself, it is possible that an as yet undescribed regulatory element lies within the 60 nucleotides of region 5 that are not the CDE. As our aim was to investigate which regulatory elements are crucial in the regulation of Tnf expression, we used these results to guide our choice as to which deletions we would engineer in a series of mouse models. We decided on the removal of region 4, region 5, or region 6 alone, and the combined removal of region 4 and 5 or 4 and 6 (Figure 1C). The phenotypes associated with these mutations are described below and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phenotype Summary

| Arthritis | IBD | HVD | iBALT | Bone Marrow Nodules | Oily Fur | Embryonic Death | Lifespan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tnfdel4/+ | – | – | – | + | + | No | No | >1 year (n = 24) |

| Tnfdel4/del4 | + | +++ | – | +++ | +++ | Yes | No | 300 days (n = 34) |

| Tnfdel5/+ | – | – | – | – | – | No | No | >1 year (NA) |

| Tnfdel5/del5 | – | – | – | – | – | No | No | >1 year (n = 31) |

| Tnfdel6/+ | – | – | – | – | – | No | No | >1 year (NA) |

| Tnfdel6/del6 | – | – | – | – | – | No | No | >1 year (n = 57) |

| Tnfdel4del5/+ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | Yes | No | >200 days (n = 77) |

| Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes, E16.5 | NA |

| Tnfdel4del5/del4del5;Tnfr1+/− | +/+ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | Yes | No | 100 days (n = 2) |

| Tnfdel4del6/+;Tnfr1+/+ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes, stage unknown | NA |

| Tnfdel4del6/+;Tnfr1+/− | ++++ | ++ | + | + | +++ | No | 80% death at birth (PN1) | 20 days (n = 19) |

| BPSM1m/+ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | No | No | 200 days (n = 49) |

| BPSM1m/m | ++++ | + | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | No | No | 4–8 weeks (n = 68) |

| TNFΔARE/+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | No | No | 200 days |

| TNFΔARE/ΔARE | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | + | No | No | 4–12 weeks |

Summary of the phenotypes observed in mice with various mutations in Tnf 3′ UTR. For lifespan values, n refers to the number of mice that have reached the specified age.

TNFdel4 Mice

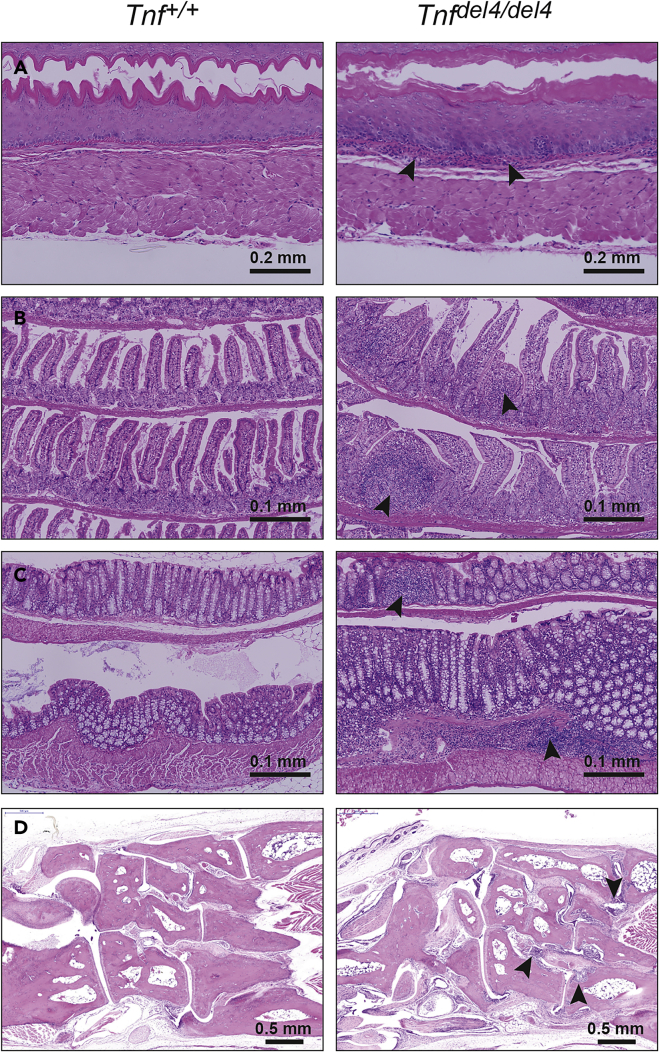

Region 4 of Tnf 3′ UTR contains the ARE that are bound by TTP to regulate Tnf post-transcriptionally (Taylor et al., 1996). The mutations in TNFΔARE and BPSM1 mice are both dominant and lead to RA of similar severity (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999; Lacey et al., 2015). Surprisingly, deletion of region 4 in our reporter system led to a smaller increase in GFP expression than the increase caused by the BPSM1 mutation (Figure 1). Moreover, we have shown that the cloning strategy used to produce TNFΔARE mice left in region 6 a 132-nucleotide vector sequence containing a loxP site and several restriction sites. Owing to our results showing a strong cooperation of regions 4 and 6, we suspected that this 132-nt insertion in region 6 might have altered the expression of Tnf more than a deletion of the ARE alone would have. Therefore, we generated TNFdel4 mice, in which we deleted the ARE from Tnf 3′ UTR using CRISPR (Wang et al., 2013; Kueh et al., 2017), carefully leaving any other region of the UTR unmodified (see Figure S1 and Table S1). Heterozygous TnfΔARE/+ mice developed arthritis, IBD (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999), and HVD (Lacey et al., 2015), whereas heterozygous Tnfdel4/+ mice developed none of these ailments, even at 18 months of age (Figure 2). Homozygous Tnfdel4/del4 mice, by contrast, developed esophagitis, ileitis, and colitis (Figure 2), but only mild arthritis, and no heart disease (Figure S2). Arthritis became severe in older Tnfdel4/del4 mice (>200 days-old), but they never showed heart valve problems. TnfΔARE/ΔARE mice succumbed to disease between 5 and 12 weeks of age (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999), whereas Tnfdel4/del4 mice lived up to 1 year. Like in TNFΔARE mice, concomitant ablation of TNFR1 prevented all pathologies in Tnfdel4/del4 mice (data not shown). Thus, it appears that the deletion of the ARE from Tnf 3′ UTR is less detrimental to mouse health than previously reported, this difference most likely stemming from the insertion of a loxP site and some vector sequences in region 6 of the UTR in TNFΔARE mice.

Figure 2.

In Vivo Deletion of the ARE from Tnf 3′ UTR Causes Severe IBD, but Only Mild Arthritis

(A–C) Sections through the esophagus (A), ileum (B), and colon (C) show the infiltration of numerous immune cells (arrowheads) within these organs in Tnfdel4/del4 mice.

(D) Sections through the ankle of 200-day-old Tnfdel4/del4 mice display signs of moderate arthritis (arrowheads).

See also Figures S2 and S3.

We have shown recently that, in addition to RA and HVD, BPSM1 mice (both heterozygotes and homozygotes) also develop tertiary lymphoid organs such as inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) in the bone marrow (Seillet et al., 2019). Likewise, both TNFdel4 heterozygous and homozygous mice also developed iBALT and NLH (Figure S2, and data not shown). The absence of any phenotype in Tnfdel4/+ mice reinforces our previous conclusion that neither iBALT nor NLH has a pathogenic role, in line with the normal presence of these structures in species such as rats or rabbits.

In addition to these previously described phenotypes, Tnfdel4/del4 mice were immediately identifiable even before weaning by their wet/oily-looking fur. This was due to the increase in size of their sebaceous glands (Figure S3), a phenotype that was not present in BPSM1 or TNFΔARE mice.

TNFdel5 Mice

Region 5 of Tnf 3′ UTR contains the CDE (Stoecklin et al., 2003), a 17-nt stem-loop motif recognized by Rc3h1 (Roquin-1) and Rc3h-2 (Roquin-2) (Leppek et al., 2013; Mino et al., 2015). As Leppek et al. found that binding of Roquin-1 initiates degradation of Tnf mRNA and limits TNF-α production in macrophages, we anticipated that deletion of the CDE from Tnf 3′ UTR would cause an inflammatory phenotype in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we deleted the CDE from Tnf 3′ UTR using CRISPR to generate the TNFdel5 strain. Contrary to our expectations, Tnfdel5/+ and Tnfdel5/del5 mice failed to develop any obvious inflammatory phenotype in a 2-year observation period (data not shown), suggesting that the CDE by itself only has a minor role in regulating the steady-state expression of Tnf.

TNFdel6 Mice

We have shown that the 76-nt-long region 6 of Tnf 3′ UTR contains a regulatory element (NRE) that strongly cooperates with the ARE in the downregulation of Tnf expression. In our GFP reporter system in HEK293 cells, region 6 appeared involved in the downregulation of Tnf by the RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) Zc3h12a and Zc3h12c (Lacey et al., 2015). To narrow down this effect to a shorter motif within region 6, we compared the sequences of Tnf 3′ UTRs from 18 different species and identified three particularly well-conserved motifs (denoted 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3; see Figure S4). We then generated additional reporter constructs missing both region 4 and one of regions 6.1, 6.2, or 6.3 (see Figures S1 and S4). None of these constructs showed a synergy as high as that observed with the construct missing region 4 and the entire region 6. Another set of three reporter constructs (4 + 6.4, 4 + 6.5, and 4 + 6.6, with regions 6.4, 6.5, and 6.6 covering the entire region 6, see Figure S1) led to a similar result (data not shown), and we could not identify within region 6 a discrete motif that would account for the whole effect of region 6 deletion. However, all these constructs showed a marked increase in GFP reporter activity relative to the construct lacking region 4 alone (Figure S4), suggesting that all three sub-regions 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3 participate in the effect, maybe by defining a particular secondary structure of Tnf 3′ UTR. We used CRISPR to delete the 76-nucleotide region 6 from Tnf 3′ UTR and generate the TNFdel6 strain. Tnfdel6/+ and Tnfdel6/del6 mice also failed to develop any obvious inflammatory phenotype within 2 years (data not shown), demonstrating that deleting the NRE alone is not sufficient to alter Tnf expression enough to cause an inflammatory disease.

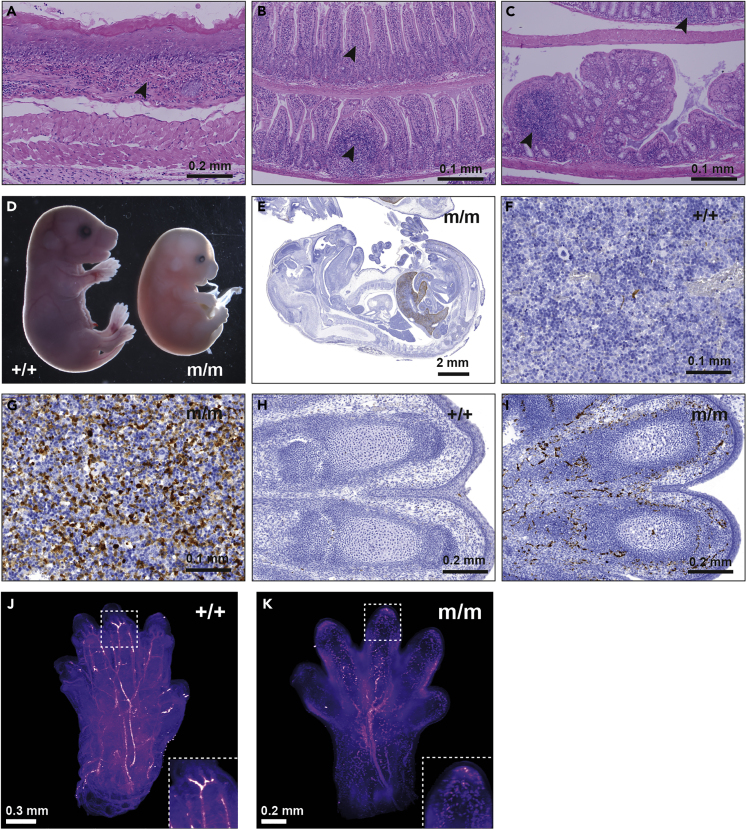

TNFdel4del5 Mice

The deletion of both regions 4 and 5 from Tnf 3′ UTR resulted in higher GFP expression than the deletion of either region alone in our reporter system (Figure 1). We thus used CRISPR to generate the TNFdel4del5 strain with the Tnf 3′ UTR lacking both regions. Tnfdel4del5/+ mice presented at weaning with a wet/oily-looking fur (Figure S3) and a slightly smaller size than their WT littermates, a phenotype similar to that observed in Tnfdel4/del4 mice. Tnfdel4del5/+ mice developed esophagitis, ileitis, and colitis, as well as iBALT and NLH (Figures 3 and S3, and data not shown). Unlike Tnfdel4/del4 mice, however, they also developed arthritis and HVD at an early age (Figure S5), and rarely reached 250 days of age. Thus, the concomitant deletion of both regions 4 and 5 from Tnf 3′ UTR drastically increases the severity of the consequences due to the deletion of region 4 alone and shows that regions 4 and 5 of Tnf 3′ UTR cooperate in vivo to regulate the expression of Tnf. The complete absence of the heart valve phenotype in TNFdel4 mice and its presence in TNFdel4del5 mice suggests that the regulation also involves cell type specificity, maybe due to tissue-specific expression of the proteins that recognize these different regulatory elements of Tnf 3′ UTR.

Figure 3.

Concomitant Deletion of Region 5 Increases the Severity of the Inflammatory Phenotype Due to the Removal of the ARE from Tnf 3′ UTR

(A–C) Esophagitis (A), ileitis (B), and colitis (C) in a 100 day-old Tnfdel4del5/+ mouse. Arrowheads indicate immune cell infiltration in these tissues.

(D) Homozygote Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 (m/m) embryos die at E16.5 and appear devoid of major blood vessels.

(E–I) (E) Active Caspase-3 staining of an E15.5 homozygote TNFdel4del5 embryo (m/m) shows extensive cell death in the liver. Active Caspase-3-stained liver of WT (F) and homozygote (G) E16.5 TNFdel4del5 embryos at 40× magnification. 20× magnification shows death of blood vessels in the digits of an E16.5 TNFdel4del5 homozygote embryo (I) and the absence of cell death in WT embryo (H) at the same stage of development.

(J and K) Label-free light sheet imaging of hemoglobin autofluorescence in cleared front paws of WT (+/+) and homozygote Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 (m/m) E16.5 embryos. Still image from Video S1.

See also Figures S3, S4 and S5.

No Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 homozygote mouse was found in the litters from heterozygote parents. Therefore, we arranged timed matings to determine the time of death of homozygous embryos. Examination of these embryos indicated that development proceeded normally until embryonic day (E) 15.5. At E16.5, however, homozygous embryos appeared smaller, and their limbs, heads, and tails were very pale due to the disappearance of major blood vessels that were clearly visible in their WT and heterozygous littermates (Figure 3). No homozygous embryo was found alive after E16.5. Light sheet microscopy clearly showed the fragmentation of the vascular system in the limbs of these embryos (Video S1). Staining histological sections for active caspase 3 confirmed the death of endothelial cells in the limbs and revealed massive apoptosis of hepatocytes in the liver, which was also devoid of most blood vessels (Figure 3). In addition, the proportion of nucleated erythroblasts was three times higher in Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 homozygote embryos than in controls (Figure S5). We conclude that Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 homozygote embryos die of vascular collapse and liver degeneration around E16.5.

Loss of TNFR1 once again completely prevented all the pathologies observed in Tnfdel4del5/+ and Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 animals, and compound Tnfdel4del5/del4del5/Tnfr1−/− mice lived and reproduced without developing any symptoms (data not shown). Interestingly, loss of a single allele of Tnfr1 also prevented the embryonic death of Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 animals (n = 2). However, Tnfdel4del5/del4del5/Tnfr1+/− mice developed arthritis, HVD, iBALT, and IBD (Figure S6) and only lived to ∼100 days. This result exemplifies the delicate balance between TNF and TNFR1 in the signaling of this cytokine.

Altogether, these data show that, as suggested by the results in our GFP reporter system, regions 4 and 5 of Tnf 3′ UTR cooperate to regulate expression of TNF in vivo and that this cooperation is necessary to prevent embryonic death.

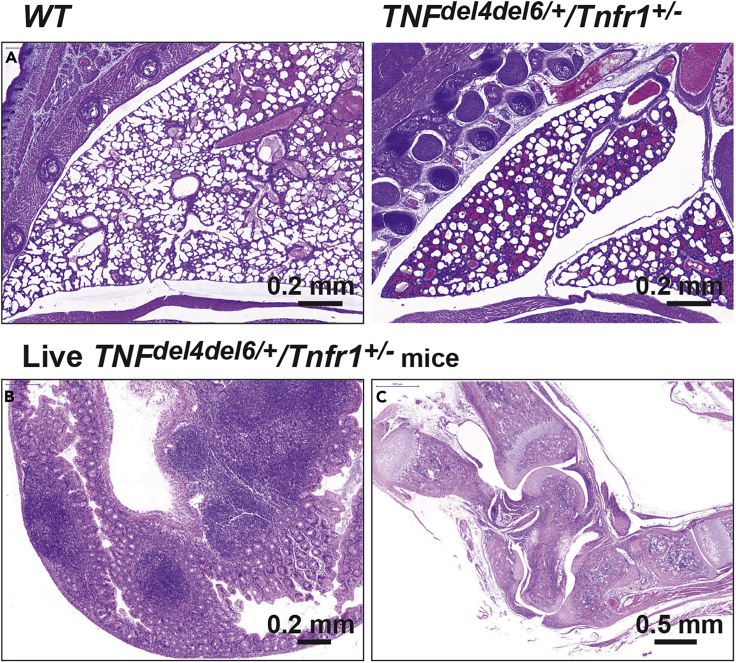

TNFdel4del6 Mice

Deletion of regions 4 and 6 from Tnf 3′ UTR led to the highest level of GFP expression in our reporter system. Therefore, we expected that the phenotype associated with this double deletion in vivo would be remarkable. To generate TNFdel4del6 mice, we first attempted to create the additional TNFdel6 mutation in Tnfdel4/del4 embryos, or to create the additional TNFdel4 mutation in Tnfdel6/del6 embryos. These approaches failed to generate viable animals harboring both mutations on the same allele, suggesting that the TNFdel4del6 mutation may be lethal on a TNFR1 WT background. We then designed a strategy that involved generating the double deletion simultaneously with a repair template and used this approach in WT embryos and in Tnfr1−/− embryos. While no animal bearing the double mutation was generated on the WT background, Tnfdel4del6/del4del6/Tnfr1−/− and Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1−/− animals were generated successfully and did not present with any phenotype (data not shown). To examine the effects of the homozygous deletion of both regions 4 and 6 in vivo, we crossed Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1−/− animals with WT partners and examined their progeny. About 80% of Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− animals died within a few hours after being born. Histopathological analysis indicated that these animals had failed to initiate respiration, and all showed underinflated lungs (Figure 4). Twelve Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− animals survived to 20–33 days. These animals were very runty and showed signs of arthritis (deformed wrists and ankles) from 7 days of age, but their fur did not look wet or oily. Histological examination of 20-days old Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− animals revealed the presence of IBD in the gut, large pannus tissue invasion in the synovial joints, and iBALT in the lungs, but only limited inflammation was seen in the heart valves or aortic root (Figure 4, and data not shown).

Figure 4.

Phenotypes Due to the Combined Deletion of Regions 4 and 6

(A) Underinflation of lungs is the cause of the death of most Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− pups soon after birth. Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− pups that survive develop IBD (B) and extremely severe arthritis (C).

(B) Immune cell infiltration in the cecum of a 20 day-old Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− pup as seen by H&E staining.

(C) Dislocated and pannus-infiltrated ankle in the same animal as in (B).

The severity of the phenotype in Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/− animals prevented us from generating Tnfdel4del6/del4del6/Tnfr1+/− animals or Tnfdel4del6/+/Tnfr1+/+ animals.

Even though the deletion of region 6 had no consequence on general health, the concomitant deletion of regions 4 and 6 of Tnf 3′ UTR in vivo led to the most severe phenotype because it was observed in heterozygous mice with a single functional Tnfr1 allele.

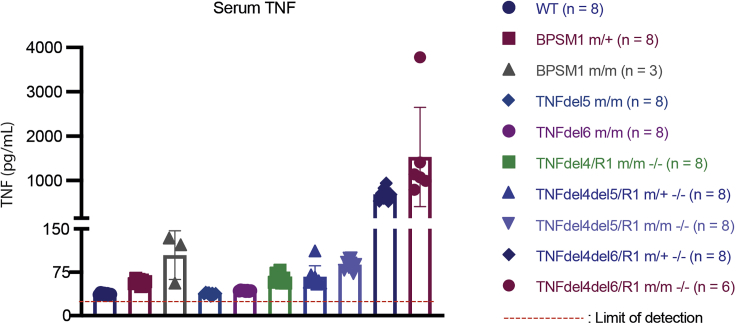

To estimate how these mutations affected the levels of circulating TNF in vivo, we took advantage of the fact that the concomitant loss of Tnfr1 prevented all the pathologies due to an increase in TNF expression. On the Tnfr1−/− background, we were able to generate healthy adult mice with heterozygote or homozygote TNFdel4del5 or TNFdel4del6 mutations. The ELISA results (Figure 5) show that the levels of TNF in the serum are strikingly similar to those predicted by the reporter assays in HEK293 cells described in Figure 1. Levels of circulating TNF, however, are not sufficient to explain some of our observations. For example, the levels of TNF in homozygous BPSM1 (m/m) and TNFdel4del6 (both m/+ and m/m) mice are superior to those of TNFdel4del5 homozygous mutants, yet neither BPSM1m/m nor TNFdel4del6 (heterozygote at least) mutant mice die at E16.5 as Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 animals do.

Figure 5.

Serum TNF Levels Vary Greatly According to Mutations in Tnf 3′ UTR

TNF levels were determined by ELISA as described. Data represent mean ± SEM of the number of animals indicated.

Hematopoietic Reconstitution

We have shown previously that the hematopoietic system of lethally irradiated WT C57BL/6 recipients can be successfully reconstituted with bone marrow cells from BPSM1m/m/Tnfr1−/− healthy animals, and that the recipient mice proceed to develop the disease within 2 months following transplantation (Lacey et al., 2015). We performed similar experiments with WT, Tnfdel4/del4/Tnfr1−/−, Tnfdel4del5/del4del5/Tnfr1−/−, and Tnfdel4del6/del4del6/Tnfr1−/− as healthy bone marrow donors. Recipients of Tnfdel4/del4/Tnfr1−/− bone marrow cells had developed NLH, mild HVD, mild IBD, and mild arthritis 5 months after transplantation (Figure S5). Recipients of Tnfdel4del5/del4del5/Tnfr1−/− cells reconstituted their hematopoietic system, but they became sick 3 weeks after transplantation. Histological analysis showed that they had developed severe IBD, particularly colitis (Figure S5). Recipients of Tnfdel4del6/del4del6/Tnfr1−/− cells became ill 7–9 days following transplantation, with clear signs of anemia and bone marrow failure (Figure S7). Histological examination revealed the occurrence of acute liver necrosis in all mice transplanted with Tnfdel4del6/del4del6/Tnfr1−/− cells (Figure S8). Thus, it appears that the severity of the phenotypes developing after hematopoietic reconstitution largely depends on the amount of TNF produced by donor cells and the tolerance of certain organs (e.g., liver, gut in particular) to high levels of TNF.

Discussion

AREs found in the 3′ UTR of many messenger RNAs have long been recognized as the most common determinants of RNA stability in mammalian cells (Shaw and Kamen, 1986; Chen and Shyu, 1995). A number of RBPs bind to AREs and stabilize the transcripts, whereas others facilitate their degradation (Barreau et al., 2005). Recent technological advances have allowed the identification of more than 1,500 RBPs, which are involved in the maturation, stability, transport, and degradation of cellular RNAs (Gerstberger et al., 2014). RBPs may directly bind to RNA or be integral parts of macromolecular protein complexes that bind to RNA, such as the RNA exosome. Despite the growing amount of data collected on RBPs, many questions remain unanswered. Our understanding of how binding specificity is achieved and how the regulatory function of an individual RBP is influenced by synergy and competition with other RBPs is still far from resolved. In addition, more than 100 different types of RNA modifications have been identified, mostly in the form of naturally occurring modified nucleosides (Grosjean, 2015). While most of these modifications were discovered in abundant molecules such as tRNAs, rRNAs, and small non coding RNAs, recent studies have shown that they occur in all cellular RNAs, including mRNAs, and that they can be reversible (Jonkhout et al., 2017). The challenge of the new field of epitranscriptomics is to understand the functional consequences of mRNA modifications (Jones et al., 2020).

The ARE present in Tnf 3′ UTR has been identified as a crucial part of the post-transcriptional regulation of this gene (Han and Beutler, 1990), and a first mouse model, TNFΔARE, demonstrated the importance of this type of regulation for the prevention of auto-inflammatory diseases such as RA and IBD (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999). TTP was found to bind Tnf ARE, and its ablation from the mouse genome also led to autoinflammatory symptoms, partly due to Tnf dysregulation (Taylor et al., 1996).

The discovery that the insertion of a retrotransposon in Tnf 3′ UTR was the cause for the development of chronic polyarthritis and HVD in BPSM1 mice (Lacey et al., 2015) prompted us to reconsider the role of the 3′ UTR in the regulation of TNF levels. Three regions of Tnf 3′ UTR seem to act in concert to regulate Tnf expression post-transcriptionally. The genetic models described here provide strong evidence that post-transcriptional regulation of TNF expression is a critical mechanism to maintain low levels of serum TNF in mice. The variety and the severity of the phenotypes highlight the importance of post-transcriptional regulation in the control of TNF expression in health and disease. In addition, this is the demonstration that excessive TNF can cause embryonic or perinatal death.

Many studies have documented the role of numerous transcription factors such as the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and NF-κB on Tnf promoter to explain the sudden increase of TNF in response to many stimuli (Falvo et al., 2010). Early studies of human TNF transgenic mice showed that, irrespective of the promoter used, the replacement of TNF 3′ UTR in the transgene with that of the β-globin mRNA was sufficient to drive TNF promoter-driven TNF overexpression and the development of tissue-specific inflammation in mice (Keffer et al., 1991). TNF promoter was shown to be constitutively active in a number of cell lines (HeLa, NIH3T3, and L929), and TNF 3′ UTR effectively canceled reporter gene expression in HeLa and NIH3T3cells, but not in L929 cells (Kruys et al., 1992). In HEK293 cells, we have shown that Tnf promoter is able to drive a robust expression of GFP, and that the expression of GFP can be extinguished by swapping the SV40 polyadenylation sequence for the 3′ UTR of Tnf in the reporter (Figure S9). Although this certainly does not exclude a role for transcription factors in boosting TNF expression at the promoter level in inflammatory conditions, it also opens the possibility that some of these transcription factors could produce a similar result by inhibiting the expression of some of the RBPs that participate in the down-regulation of TNF levels through the 3′ UTR of its mRNA.

The increase in the size of sebaceous glands and the associated oily-looking fur in TNFdel4 and TNFdel4del5 mice is rather surprising because it was not observed in TNFΔARE, BPSM1, and TNFdel4del6 mice. A recent report indicated that sebaceous gland homeostasis was regulated by a population of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) residing within hair follicles in close proximity to the glands (Kobayashi et al., 2019). These RORγt + ILCs were found to negatively regulate sebaceous gland function by expressing TNF and lymphotoxins LTα3 and LTα1β2, which downregulated Notch signaling. The authors reported that sebaceous glands were hyperplastic in the triple knockout (Tnf−/-, Ltα−/-, Ltβ−/-) mice, whereas none of the single knockout showed the phenotype. The fact that TNF overexpression can generate a similar phenotype certainly warrants further investigation.

Our results provide strong evidence that several RBPs participate in the post-transcriptional regulation of Tnf mRNA levels in vivo, and that the differential distribution of these proteins within tissues and cell types is probably the cause of the phenotypic variations observed in our mutant mice. The disintegration of the vascular system in TNFdel4del5 homozygote E16.5 embryos suggests that a particular RBP is present in these cells to prevent an excessive expression of TNF, and that this RBP acts through regions 4 and/or 5 of Tnf 3′ UTR. It is remarkable that none of the other mutant mice, in particular those that express higher levels of circulating TNF, shows this phenotype. Whether these cell type-specific RBPs act as part of a ribonuclease complex such as the RNA exosome (Morton et al., 2018) or the CCR4-NOT complex (Collart, 2016) will of course require their identification. Interfering with the TNF post-transcriptional regulatory system may represent a therapeutic avenue for manipulation of TNF expression. Indeed, Allotrap 1258, a synthetic peptide derived from the heavy chain of HLA Class I, inhibited concanavalin A- and LPS-induced human and mouse TNF production in vitro and in vivo (Iyer et al., 2000). Allotrap 1258-mediated inhibition required the presence of Tnf 3′ UTR to be effective, suggesting that it may activate a component of the RNA degradation complex for its activity. The clear parallels between our in vivo results and the results obtained with our reporter system in HEK293 cells indicate that these cells contain at least the critical components of the Tnf post-transcriptional regulatory system, suggesting that our reporter system could be used as a basis for a screening strategy aimed at identifying regulators of TNF expression.

Limitations of the Study

This study provides mouse models demonstrating the importance of three regulatory elements within the 3′ UTR of the Tnf gene but does not identify new RBPs that may explain how these elements participate in the control of Tnf expression.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Philippe Bouillet (bouillet@wehi.edu.au).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The reference Tnf sequence is GenBank Accession: NM_013693.3, GI : 518831586. The sequences of the Tnf 3′ UTRs found in our mutants have been deposited in GenBank: MW116778 (TNFdel4), MW116779 (TNFdel5), MW116780 (TNFdel6), MW116781 (TNFdel4del5), MW116782 (TNFdel4del6).

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Stanley, T. Kitson. M. Watters, and G. Siciliano for animal care and expertise; J. Corbin, K. Weston, and T. Nikolaou for automated blood analysis; T. Mak (The Campbell Family Institute for Breast Cancer Research) for TNFR1 KO mice; and J. Silke for TNF KO mice. This work was supported by the Australian NHMRC (Program Grant 461221, Research Fellowship 1042629, Project grant 1127885), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (Specialised Center of Research grant 7015), the Arthritis Australia Zimmer fellowship, and infrastructure support from the NHMRC (IRISS), and the Victorian State Government (OIS). The generation of TNFdel4, TNFdel5, TNFdel6, TNFdel4del5, and TNFdel4del6 mice used in this study was supported by the Australian Phenomics Network (APN) and the Australian Government through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.; Methodology, A.K., V.C.W., and P.B.; Investigation, E.Clayer, D.D., A.K. D.L., M.T., E.H. Arvell, V.C.W., and P.B.; Writing, E.Clayer, D.D., and P.B.; Visualization, E.Clayer, D.D., V.C.W., and P.B.; Funding Acquisition, P.B.; Resources, P.B.; Supervision, P.B.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: November 20, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101726.

Supplemental Information

. Label-free light sheet imaging of hemoglobin autofluorescence in cleared front paws of WT (left) and homozygote Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 (m/m) E15.5 embryos shows vascular collapse.

References

- Barreau C., Paillard L., Osborne H.B. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:7138–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.Y., Shyu A.B. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart M.A. The Ccr4-Not complex is a key regulator of eukaryotic gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2016;7:438–454. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falvo J.V., Tsytsykova A.V., Goldfeld A.E. Transcriptional control of the TNF gene. Curr. Dir. Autoimmun. 2010;11:27–60. doi: 10.1159/000289196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway A., Turner M. Cell cycle RNA regulons coordinating early lymphocyte development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2017;8:e1419. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstberger S., Hafner M., Tuschl T. A census of human RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:829–845. doi: 10.1038/nrg3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean H. RNA modification: the golden period 1995-2015. RNA. 2015;21:625–626. doi: 10.1261/rna.049866.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Beutler B. The essential role of the UA-rich sequence in endotoxin-induced cachectin/TNF synthesis. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 1990;1:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S., Kontoyiannis D., Chevrier D., Woo J., Mori N., Cornejo M., Kollias G., Buelow R. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor mRNA translation by a rationally designed immunomodulatory peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17051–17057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909219199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.D., Monroe J., Koutmou K.S. A molecular-level perspective on the frequency, distribution, and consequences of messenger RNA modifications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2020;11:e1586. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkhout N., Tran J., Smith M.A., Schonrock N., Mattick J.S., Novoa E.M. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA. 2017;23:1754–1769. doi: 10.1261/rna.063503.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keffer J., Probert L., Cazlaris H., Georgopoulos S., Kaslaris E., Kioussis D., Kollias G. Transgenic mice expressing human tumour necrosis factor: a predictive genetic model of arthritis. EMBO J. 1991;10:4025–4031. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Voisin B., Kim D.Y., Kennedy E.A., Jo J.H., Shih H.Y., Truong A., Doebel T., Sakamoto K., Cui C.Y., et al. Homeostatic control of sebaceous glands by innate lymphoid cells regulates commensal bacteria equilibrium. Cell. 2019;176:982–997 e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoyiannis D., Pasparakis M., Pizarro T.T., Cominelli F., Kollias G. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU- rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 1999;10:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruys V., Kemmer K., Shakhov A., Jongeneel V., Beutler B. Constitutive activity of the tumor necrosis factor promoter is canceled by the 3' untranslated region in nonmacrophage cell lines; a trans-dominant factor overcomes this suppressive effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1992;89:673–677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueh A.J., Pal M., Tai L., Liao Y., Smyth G.K., Shi W., Herold M.J. An update on using CRISPR/Cas9 in the one-cell stage mouse embryo for generating complex mutant alleles. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1821–1822. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey D., Hickey P., Arhatari B.D., O'reilly L.A., Rohrbeck L., Kiriazis H., Du X.J., Bouillet P. Spontaneous retrotransposon insertion into TNF 3'UTR causes heart valve disease and chronic polyarthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:9698–9703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508399112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W.S., Carballo E., Thorn J.M., Kennington E.A., Blackshear P.J. Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. Binding of tristetraprolin-related zinc finger proteins to Au-rich elements and destabilization of mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17827–17837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppek K., Schott J., Reitter S., Poetz F., Hammond M.C., Stoecklin G. Roquin promotes constitutive mRNA decay via a conserved class of stem-loop recognition motifs. Cell. 2013;153:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Zhang L., Joo D., Sun S.C. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2017;2:e17023. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino T., Murakawa Y., Fukao A., Vandenbon A., Wessels H.H., Ori D., Uehata T., Tartey S., Akira S., Suzuki Y., et al. Regnase-1 and Roquin regulate a common element in inflammatory mRNAs by spatiotemporally distinct mechanisms. Cell. 2015;161:1058–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton D.J., Kuiper E.G., Jones S.K., Leung S.W., Corbett A.H., Fasken M.B. The RNA exosome and RNA exosome-linked disease. RNA. 2018;24:127–142. doi: 10.1261/rna.064626.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka H., Fukao A., Funakami Y., Duncan K.E., Fujiwara T. Emerging evidence of translational control by AU-rich element-binding proteins. Front. Genet. 2019;10:332. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seillet C., Arvell E.H., Lacey D., Stutz M.D., Pellegrini M., Whitehead L., Rimes J., Hawkins E.D., Roediger B., Belz G.T., Bouillet P. Constitutive overexpression of TNF in BPSM1 mice causes iBALT and bone marrow nodular lymphocytic hyperplasia. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2019;97:29–38. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw G., Kamen R. A conserved AU sequence from the 3' untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell. 1986;46:659–667. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G., Lu M., Rattenbacher B., Moroni C. A constitutive decay element promotes tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA degradation via an AU-rich element-independent pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:3506–3515. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3506-3515.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G.A., Carballo E., Lee D.M., Lai W.S., Thompson M.J., Patel D.D., Schenkman D.I., Gilkeson G.S., Broxmeyer H.E., Haynes B.F., Blackshear P.J. A pathogenetic role for TNF alpha in the syndrome of cachexia, arthritis, and autoimmunity resulting from tristetraprolin (TTP) deficiency. Immunity. 1996;4:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yang H., Shivalila C.S., Dawlaty M.M., Cheng A.W., Zhang F., Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

. Label-free light sheet imaging of hemoglobin autofluorescence in cleared front paws of WT (left) and homozygote Tnfdel4del5/del4del5 (m/m) E15.5 embryos shows vascular collapse.

Data Availability Statement

The reference Tnf sequence is GenBank Accession: NM_013693.3, GI : 518831586. The sequences of the Tnf 3′ UTRs found in our mutants have been deposited in GenBank: MW116778 (TNFdel4), MW116779 (TNFdel5), MW116780 (TNFdel6), MW116781 (TNFdel4del5), MW116782 (TNFdel4del6).