Abstract

COVID-19 has forced governments to make drastic changes to healthcare systems. To start making informed decisions about cancer care, we need to understand the scale of COVID-19 infection. Therefore, we introduced swab testing for patients visiting Guy’s Cancer Centre. Our Centre is one of the largest UK Cancer Centers at the epicenter of the UK COVID-19 epidemic. The first COVID-19 positive cancer patient was reported on 29 February 2020. We analyzed data from 7-15 May 2020 for COVID-19 tests in our cancer patients. 2,647 patients attended for outpatient, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy appointments. 654 were swabbed for COVID-19 (25%). Of those tested, 9 were positive for COVID-19 (1.38%) of which 7 were asymptomatic. Cancer service providers will need to understand their local cancer population prevalence. The absolute priority is that cancer patients have the confidence to attend hospitals and be reassured that they will be treated in a COVID-19 managed environment.

Keywords: COVID-19, cancer recovery, public health, UK, prevalence

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced governments, including our own, to make drastic changes to the healthcare system to save lives. While such measures may have reduced COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there have been serious unintended consequences on society and non-COVID-19 health issues. Well-established pathways to ensure patients with cancer are diagnosed, obtain rapid treatment, and receive ongoing care have been significantly disrupted.1 This disruption is multifactorial: strong messaging to “stay at home” has been so successful that patients are frightened to attend appointments; there is little scientific literature as yet to guide clinicians about safety of cancer treatments during the pandemic; the clinical workforce has been reduced by COVID-19 illness and redeployment as well as fear about their risk exposures; and the availability and reliability of COVID-19 antigen and antibody testing remains fragmented. Currently, as cancer clinicians and academics, we are deeply concerned about the low numbers of patients presenting either to their GP or hospital services with signs and symptoms suspicious of cancer.

Since the UK is emerging from the pandemic’s first peak, cancer recovery strategies are being developed at local/national levels to address associated delayed diagnoses and treatments.1,2 However, the COVID-19 threat has not disappeared and the challenge is not just to deal with a backlog of work, but to continue to practice in a way that minimizes COVID-19 transmission. In the absence of a vaccine, it is likely that COVID-19-protected cancer pathways will be needed for months, if not years. Although questions remain about the wider consequences of a “semi-lockdown” strategy on welfare.

Recently, several case series have been published including a Consortium of 900 cancer patients with COVID-19 from >85 institutions.3 Although these initial data start to inform us how to care for cancer patients during COVID-19, there is as yet no long-term follow-up. To start making informed decisions about cancer care, it is crucial to understand the scale of COVID-19 infection in cancer patients. Therefore, we introduced swab testing for patients visiting Guy’s Cancer Centre.

Our Centre in South-East London treats approximately 8,800 patients annually (including 4,500 new diagnoses) and is one of the largest Comprehensive Cancer Centers in the UK at the epicenter of the UK COVID-19 epidemic. The first COVID-19 positive cancer patient was reported on 29 February 2020. Until 30 April 2020, a COVID-19 swab was ordered for cancer patients with symptoms necessitating hospitalization or if they were scheduled to undergo a cancer-related treatment. From 1 May 2020, COVID-19 testing was introduced as standard of care, with about 25% of patients being swabbed daily depending upon staff and testing kit availability. An analysis of the first 156 COVID-19 positive cancer patients (29th February until 12th May 2020) at our Centre has been published elsewhere and focuses specifically on the cancer patient characteristics indicative of COVID-19 severity and death.4

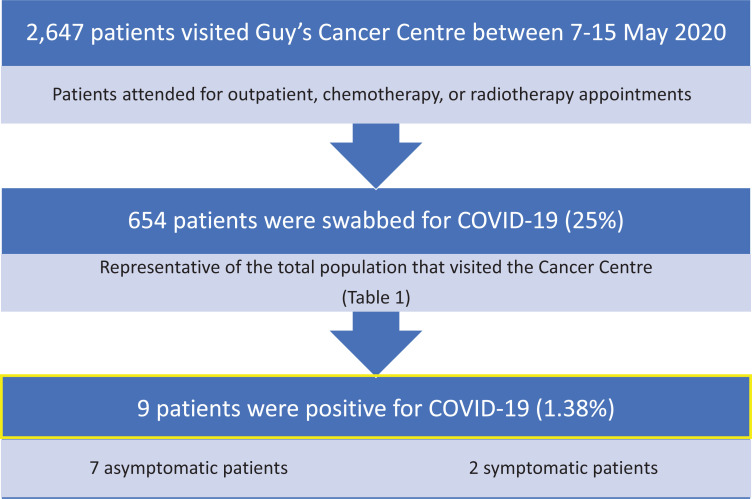

Here, we analyzed data from 7-15 May 2020 (i.e. 6 consecutive work days) for COVID-19 test results in all cancer patients at our Centre. All data was collected and analyzed as part of Guy’s Cancer Cohort (Ethics Reference number: 18/NW/0297).5 2,647 patients attended for outpatient, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy appointments from across South East London (and England) (Figure 1). Of these, 654 were swabbed for COVID-19 (25%). Over 57% of patients filled out a symptom assessment form which 97% were asymptomatic. Based on their demographics and tumor characteristics, this sample can be considered to be representative of the total population (Table 1). Of the patients tested, 9 were positive for COVID-19 (1.38%) of which 7 were asymptomatic. Reassuringly, patients with multiple attendances for radiotherapy or anti-cancer treatment were not at higher risk of infection.

Figure 1.

Overview of patients visiting Guy’s Cancer Centre between 7-15 May 2020.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Cancer Patients Visiting Guy’s Cancer Centre From 7-15 May 2020.

| Cancer patients attending cancer center (N = 2647) | Cancer patients tested (N = 654) | COVID-19 positive cancer patients (N = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (Q1-Q3) | 61.90 (53.10-71.10) | 62.00 (53.10-70.50) | 53.70 (39.30-60.20) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1221 (46.10) | 270 (41.30) | 6 (66.70) |

| Female | 1426 (53.90) | 384 (58.7) | 3 (33.30) |

| Tumor type | |||

| Breast | 454 (17.20) | 131 (20.00) | 1 (11.10) |

| Urology | 356 (13.40) | 77 (11.80) | 1 (11.10) |

| Head and Neck | 114 (4.30) | 26 (3.90) | 0 (0.00) |

| Gastro-Intestinal | 517 (19.50) | 137 (21.00) | 2 (22.20) |

| Lung | 294 (11.10) | 78 (11.90) | 1 (11.10) |

| Gynecology | 299 (11.30) | 73 (11.20) | 0 (0.00) |

| Hematology | 225 (8.50) | 40 (6.12) | 0 (0.00) |

| Other | 388 (14.70) | 92 (14.10) | 4 (44.40) |

| Appointment type | |||

| Chemotherapy | 511 (19.30) | 152 (23.20) | 2 (22.20) |

| Radiotherapy | 533 (20.10) | 94 (14.40) | 1 (1.10) |

| Outpatients | 1603 (60.60) | 408 (62.39) | 6 (66.67) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1232 (46.50) | 293 (44.80) | 2 (22.20) |

| Black | 346 (13.10) | 65 (9.90) | 2 (22.20) |

| Asian | 70 (2.60) | 16 (2.50) | 0 (0.00) |

| Mixed | 33 (1.20) | 5 (0.80) | 0 (0.00) |

| Other | 50 (1.50) | 6 (0.90) | 0 (0.00) |

| Missing | 926 (35.00) | 269 (41.10) | 5 (55.60) |

| SES | |||

| Low | 2265 (85.50) | 570 (87.20) | 7 (77.80) |

| Middle | 48 (1.80) | 8 (1.20) | 0 (0.00) |

| High | 182 (6.90) | 37 (5.70) | 1 (11.10) |

| Missing | 148 (5.60) | 39 (6.00) | 1 (11.10) |

An awareness of the COVID-19 prevalence in asymptomatic cancer patients, while helpful, is only one aspect necessary to develop a successful cancer recovery strategy. It will be essential to understand and manage contamination of the physical environment, ensure ongoing availability and use of personal protective equipment plus viral antigen and antibody testing. Moreover, knowledge of COVID-19 status during cancer treatment can allow clinicians to make tailored decisions about timing and type of therapy. All asymptomatic COVID-19 positive patients had a conversation with their treating clinician about impact on their care.

Based on data from the Office for National Statistics, between 28 April-10 May 2020 an average of 0.27% of the community population had COVID-19 (95%CI: 0.17-0.41). However, for those working in patient-facing healthcare or resident-facing social care roles, this was estimated at 1.33% (95CI%: 0.39-3.28).6 Nevertheless, London has been the region hardest hit by COVID-19, so the rate of 1.38% among asymptomatic cancer patients, the majority of whom will have been shielding, is likely to be more representative of the local situation. A meta-analysis of prevalence studies in China recently reported a prevalence of COVID-19 of 2.59% (95% CI, 1.72% to 3.90%) in the cancer population.7 This number is 1.9 times higher than ours, and may be a reflection of differences in lock-down strategies and timings of the pandemic. In addition, it needs to be noted that there may be variability in the accuracy of RT-PCR testing for COVID-19 as the sensitivity may vary by type of specimen.8 However, this “snapshot” of prevalence is not enough for an evolving situation. To our knowledge most studies to date focus on the prevalence of cancer in the COVID-19 positive patients rather than the prevalence of COVID-19 in the cancer population.

Currently, in our Cancer Centre we have discontinued routine testing due to the very low prevalence of COVID-19 in asymptomatic cancer patients. We continue to screen patients closely for symptoms and have low threshold for PCR and antibody testing to ensure maintenance of a COVID-19 minimal Centre. We are closely monitoring the number of local cases and would re-implement routine swabbing in the event of a surge in COVID-19 positive infections.

Cancer service providers will need to understand their local cancer population prevalence and keep this under regular review.9 The absolute priority and need of the hour is that cancer patients have the confidence to attend hospitals and be reassured that they will be treated in a COVID-19 managed environment.

Appendix A

Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust—Oncology

Danielle Crawley

Saoirse Dolly

Andrea D’Souza

Julien de Naurois

Deborah Enting

Sharmistha Ghosh

Simon Gomberg

Sheeba Irshad

Debra Josephs

May Lei

George Nintos

Sophie Papa

Fahreen Rahman

Anne Rigg

Paul Ross

Sylva Rushan

Debashis Sarker

Elinor Sawyer

Ailsa Sita-Lumsden

Daniel Smith

James Spicer

Angela Swampillai

Kamarul Zaki

Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust—Hematology

Katherine Bailey

Richard Dillon

Paul Fields

Mary Gleeson

Claire Harrison

Shahram Kordasti

Kavita Raj

Matthew Streetley

David Wrench

King’s College London—School of Cancer and Pharmaceutical Sciences

Fidelma Cahill

Anna Haire

Charlotte Moss

Beth Russell

Richard Sullivan

Mieke Van Hemelrijck

Harriet Wylie

University of Birmingham

Richard T. Bryan

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Data collection: BR, CM, ML, SG, SD, SP and Guy’s Cancer Real World Evidence Programme. Study design: BR, CM, AR, SD, MVH. Data analysis: BR, CM, MVH, SD. Manuscript drafting: MVH, AR, SD. Final approval of manuscript: All authors and Guy’s Cancer Real World Evidence Programme. Charlotte Moss, MSc, Saoirse Dolly, PhD, Beth Russell, PhD,Contributed equally as first authors. Mieke Van Hemelrijck, PhD, Anne Rigg, PhD, Contributed equally as senior authors. Guy’s Cancer Real World Evidence Programme members presented in Appendix A. Data can be obtained by researchers via an application to the Access Committee of Guy’s Cancer Cohort. An application form can be obtained via cancerdata@gstt.nhs.uk. Guy’s Cancer Cohort, a research ethics committee approved research database (Reference number: 18/NW/0297; North West—Haydock Research Ethics Committee) of all routinely collected clinical data of cancer patients at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (GSTT), forms the basis of this observational study. Patients and public were involved in the design of Guy’s Cancer Cohort. No written consent is required as ethical approval has been provided based on opt-out. Details can be found in Moss et al. BMC Cancer 2020.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London (IS-BRC-1215-20006). The authors are solely responsible for study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. We also acknowledge support from Cancer Research UK King’s Health Partners Centre at King’s College London and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust Charity Cancer Fund.

ORCID iD: Mieke Van Hemelrijck, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7317-0858

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7317-0858

References

- 1. Hanna TP, Evans GA, Booth CM. Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(5):268–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nepogodiev D, Bhangu A. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kuderer N, Choueiri TK, Shah DP. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russell B, Moss C, Papa S, et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 outcomes in cancer patients: a first report from Guy’s Cancer Centre in London. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moss C, Haire A, Cahill F, et al. Guy’s cancer cohort—real world evidence for cancer pathways. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Office of National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey pilot: England, 14 May 2020. Published 2020. Accessed on May 14 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/england14may2020

- 7. Su Q, Hu J-X, Lin H-S, et al. Prevalence and risks of severe events for cancer patients with COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.06.23.20136200. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watson J, Whiting PF, Brush JE. Interpreting a covid-19 test result. BMJ. 2020;369:m1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, et al. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]