Abstract

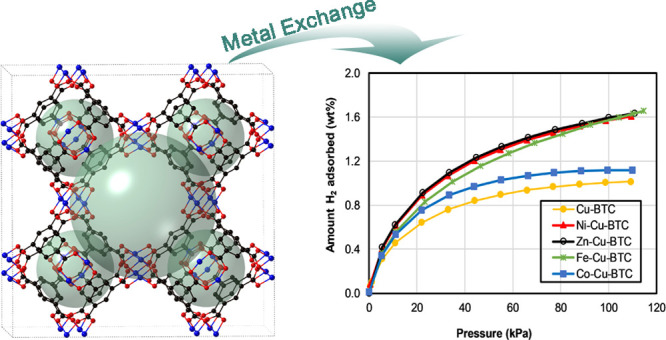

The advancement of hydrogen and fuel cell technologies hinges on the development of hydrogen storage methods. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are one of the most favorable materials for hydrogen storage. In this study, we synthesized a series of isostructural mixed-metal metal–organic frameworks (MM-MOFs) of 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate (BTC), M-Cu-BTC, where M = Zn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, and Fe2+ using the post-synthetic exchange (PSE) method with metal ions. The powder X-ray diffraction patterns of MM-MOFs were similar with those of single-metal Cu-BTC. Scanning electron microscopy indicates the absence of amorphous phases. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy of the MM-MOFs shows successful metal exchanges using the PSE method. The N2 adsorption measurements confirmed the successful synthesis of porous MM-MOFs. The metal exchanged materials Ni-Cu-BTC, Zn-Cu-BTC, Fe-Cu-BTC, and Co-Cu-BTC were studied for hydrogen storage and showed a gravimetric uptake of 1.6, 1.63, 1.63, and 1.12 wt %; respectively. The increase in hydrogen adsorption capacity for the three metal exchanged materials is about 60% relative to that of the parent MOF (Cu-BTC). The improvement of gravimetric uptake in M-Cu-BTC (where M = Ni2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+) is probably due to the increase in binding enthalpy of H2 with the unsaturated metal sites after the partial exchange from Cu2+ to other metal ions. The higher charge density of metal ions strongly polarizes hydrogen and provides the primary binding sites inside the pores of Cu-BTC and subsequently enhances the gravimetric uptake of hydrogen.

Introduction

Having high energy density and zero-CO2 emissions, hydrogen represents a potential alternative energy source and its storage and delivery are essential components in the development of fuel-cell hydrogen technologies.1,2 Several materials have been tested for H2 storage, including physisorption and chemisorption materials.2 However, no solid-state storage system has satisfied the 2020 U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) capacity targets of 4.5 wt % (in gravimetric terms) and 30 g L–1 H2 (in volumetric terms) at the operating temperature ranges of −40 to 60 °C and at pressures below 100 atm.3 In physisorption materials, H2 molecules are adsorbed on the surface of the pores in the material, there is no activation energy involved, and the interaction between H2 and the material is low. In addition, their fast kinetics, full reversibility, and manageable heat during refueling—characteristics that are difficult to achieve when using chemisorption materials—make the use of physisorption materials especially advantageous over chemisorption materials.4 In this respect, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), which are physisorption materials, are promising for H2 storage.5−11 These materials contain micropores and channels with a specific topological framework and adjustable surface area and pore size. MOFs are synthesized using solvothermal reactions, which combine the constituent metal and organic ligands using organic solvents such as dimethylformamide (DMF) and diethyl formamide (DEF), and can be designed from various combinations of metal ions and organic ligands. The topological framework and pore size of the MOFs depend on the metal ions and organic ligands used. More importantly, MOFs have high surface areas and permanent porosity, both of which are attractive for use in H2 storage systems. The pore size and framework topology have been tuned to obtain high-surface-area materials that effectively improve the H2 adsorption properties. Although a wide range of MOFs have been tested for H2 adsorption, and some showed promising storage capacities in the cryogenic state, their capacities are insignificant at ambient pressure and temperature.8 These exceptional behaviors of MOFs with a unique framework give unlimited prospects to make precise required dynamic sites and create MOFs outstanding candidates for hydrogen storage applications.8,9

Cation exchange is an attractive strategy to modify the active sites of secondary building units (SBU) in MOFs.12 This strategy exceptionally enhances the properties of MOF materials for various applications. Although, single-metal MOF materials were well studied for hydrogen adsorption, mixed-metal MOFs (MM-MOFs) were rarely investigated.13−17 The expansion of MM-MOF materials is of exclusive concern since the assimilation of more metal ions can considerably increase the interaction of hydrogen molecule with the metal sites and the selectivity of MOF adsorption.18 A practical technique for the production of MM-MOFs is a post-synthetic exchange (PSE) method for metal ion or transmetalation that contains the replacement of the SBU metal nodes with another metal ion.19 Copper-based MOF, Cu-BTC, is a highly investigated material in which Cu(II) metal units are linked by benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylate (BTC) linkers.20 The coordinated water molecule in the axial position of the paddlewheel Cu2+ centers of the structure can be removed by heating. This creates potential active sites for hydrogen adsorption. Although hydrogen adsorption in Cu-BTC has been investigated, the hydrogen adsorption of this material in MM-MOFs has not been reported before.21 It is known that the equivalent Zn-BTC with isostructural MOF can be made from a zinc source.22 It is also known that MM-MOFs of Zn-BTC can be made using different transition divalent metal ions (M2+ = Cu, Co, and Fe) for catalysis.23 Cu-Zn-BTC22 and Cu-Ru-BTC24 of MM-MOFs have also been reported. Cu-BTC has been exceptionally well recognized for its high selectivity in gas storage, especially when the axial aqua ligands are detach via activation.20 Activation provides unsaturated metal sites without influencing the rigid framework of the MOF. The highest BET surface area reported for Cu-BTC is about 1944m2/g by Yaghi and co-workers.25 The highest gravimetric H2 uptake reported for HKUST is ∼2 wt % at 77 K and low pressure and about 3–3.5 wt % at 77 K and higher pressure.25 These studies provide evidence that the MM-Cu-BTC is a reasonable system to expand the concept of metal exchange for hydrogen storage. A series of MM-MOFs of Mn3[(Mn4Cl)3(BTT)8(CH3OH)10]2 (BBT3– = 1,3,5-benzenetristetrazolate) have been reported for H2 adsorption.13 All these MM-MOFs shows high H2 uptake from 2.00 to 2.29 wt % at 77 K and 900 Torr. The reason for high heat adsorption (10.1 kJ mol–1) is due to the coordination of H2 with unsaturated Mn2+ sites as confirmed by powder neutron diffraction experiments.13 The enthalpy of adsorption is even higher in the case of MM-MOF of the Co2+/Mn2+ system (10.5 kJ mol–1). A higher H2 uptake with 23% was reported for Co-Zn-ZIF-8 in comparison to Zn-ZIF-8 due to the higher affinity of Co2+ with H2.26 Recently, Kapelewski et al. showed a record high hydrogen uptake in the Ni-based MOF, Ni2(m-dobdc) (m-dobdc4– = 4,6-dioxido-1,3-benzenedicarboxylate) at near ambient temperature.27 Ni2(m-dobdc) showing a usable volumetric capacity between 100 and 5 bar of 11.0 g/L at 25 °C and 23.0 g/L with temperature swing from −75 to 25 °C, which makes this MOF the highest-performing physisorption material so far.27 The high volumetric uptake in Ni2(m-dobdc) was attributed to the increase in binding enthalpy of H2 with the unsaturated Ni2+ metal sites.27,28 Large binding enthalpies in this MOF stemmed from the highly polarizable Ni2+ adsorption sites and dense packing of the H2 within the material. Three-pulse electron spin echo modulation (3p ESEEM) study of deuterated hydrogen gas HD adsorption/desorption in Cu-Zn-BTC reveals the adsorption sites with higher adsorption enthalpy at the local environment of the metal ions.29 The objective of this paper is to synthesize a series of isostructural mixed-metal metal–organic frameworks (MM-MOFs) of 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate (BTC), M-Cu-BTC, where M = Zn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, and Fe2+ using the PSE method with metal ions. The merits of the synthesized materials were thoroughly characterized using different techniques. In addition, hydrogen adsorption isotherms were measured to determine the uptake capacities.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of MOFs

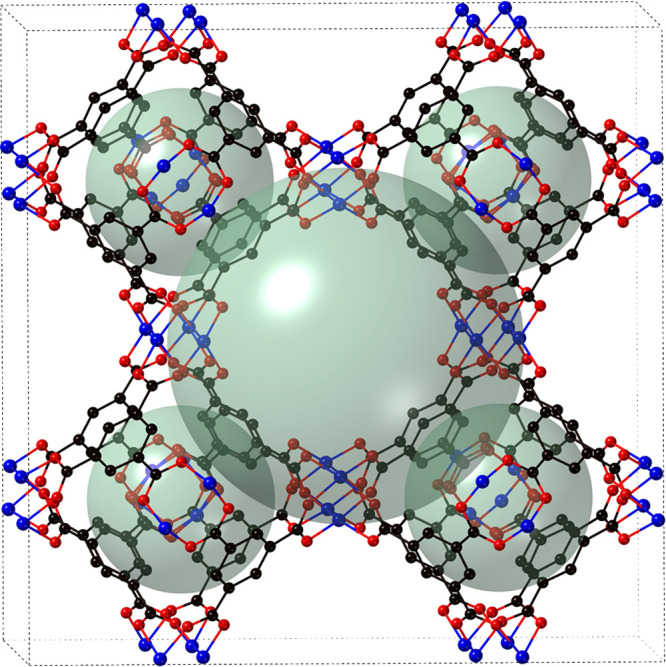

Chui and co-workers were the first to discover Cu-BTC15 and called it HKUST-1. It is a highly porous MOF of [Cu3(BTC)2(H2O)3]n, which contains interconnected [Cu2(O2CR)4] units, where R is an aromatic ring (Figure 1). The 3D framework has accessible porosity of 40% of the solid with a channel pore size of 1 nm.20 The crystals structure of Cu-BTC contains dimeric cupric tetracarboxylic secondary building units with a Cu–Cu separation of 2.628(2) Å. The neutral network contains 12 carboxylic oxygen atoms from the two BTC ligands that are coordinated to four sites of each of the three Cu2+ ions. Therefore, each Cu atoms satisfy its coordination geometry, showing an octahedral geometry with aqua ligands in axial positions. The BTC provides a motif with threefold symmetry, and the tetracarboxylic unit provides a fourfold symmetry, which leads to a 3D motif with six vertices and four trimesate ions that tetrahedrally make up four of the eight triangular faces of the octahedron.

Figure 1.

Perspective view of Cu-BTC MOF along the z axis; the spheres represent the cavities in Cu-BTC.

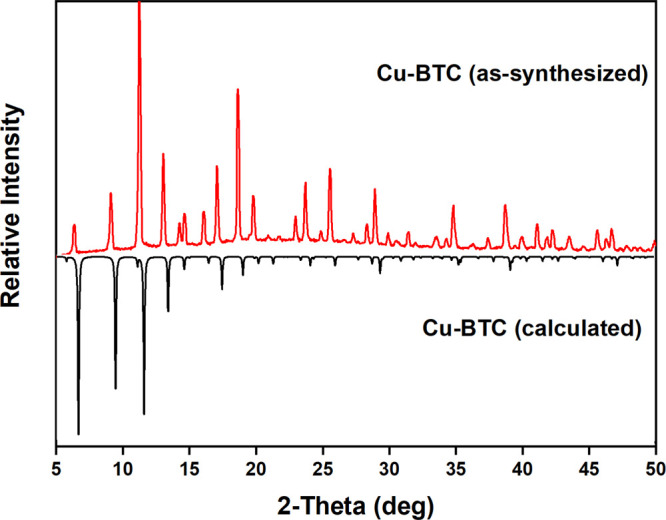

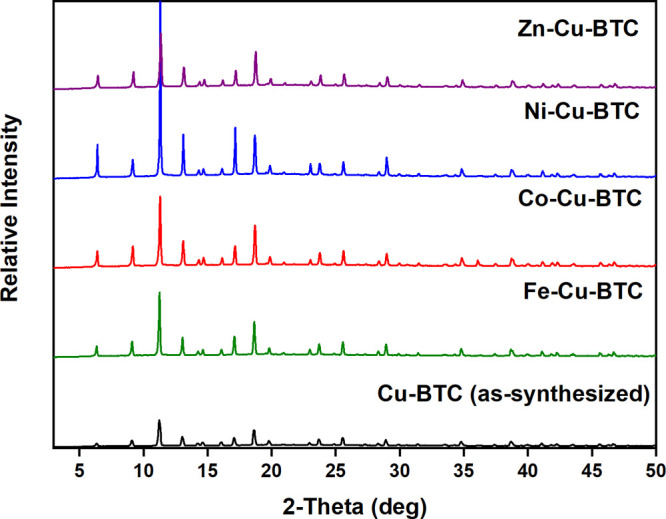

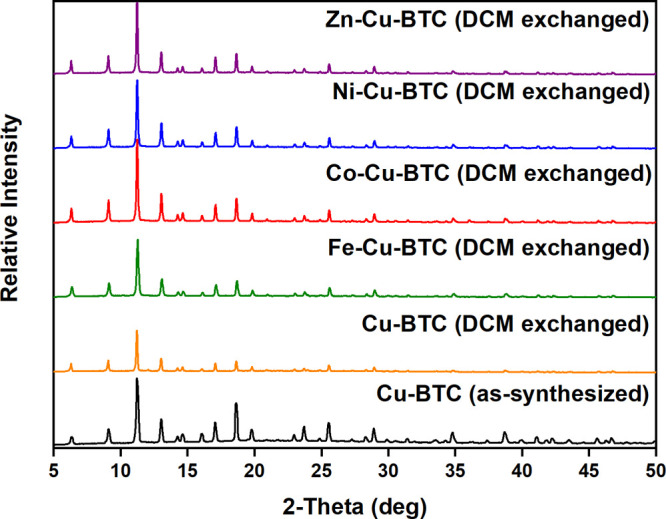

The porosity of these phases displays the absence of any metal ions in the pores. The PXRD pattern of the as-synthesized Cu-BTC shows slight differences in matching the peaks with the simulated pattern from the Cu-BTC crystal structure (Figure 2). It is shown that the intensity peak difference reflections are around 5° and 15°, which is due to the textural effect. The distinctive peaks observed at around 2θ = 15°, 25°, and 30° may be due to the presence of a small amount of unreacted copper nitrate and trimeric acid that remained in the samples. The PXRD patterns of MM-MOFs display that the modified MOFs are isostructural to Cu-BTC (Figure 3). This high crystallinity of the MM-MOFs observed in the PXRD patterns specifies that the MOFs preserved the structure after the PSE method. However, the Ni-Cu-BTC shows a much higher crystallinity compared to other metal exchanged MOFs. However, the crystallinity of the sample retained after the exchange, the change in the intensities of the peaks, and expected peak shifts after exchange may be due to the alteration of crystal lattice during the exchange process. Metal exchanged Cu-BTC contains different electronic configurations compared to Cu2+, which might disturb the intensities. A slight disorder of the lattice and existence of the new cation after metal exchange creates a noticeable peak shift from as-synthesized Cu-BTC. In addition, all PXRD patterns of the MM-MOF series exchanged with DCM after 3 days match well with the parent Cu-BTC structure (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

PXRD patterns of Cu-BTC (black, simulated from the crystal structure) and Cu-BTC (red, as-synthesized).

Figure 3.

PXRD patterns of Cu-BTC (as-synthesized) and M-Cu-BTC (as-synthesized) MOFs.

Figure 4.

PXRD patterns of Cu-BTC (DCM exchanged) and M-Cu-BTC (DCM exchanged) MOFs.

The integration of metal ions into the MOFs after PSE was recognized through ICP-MS analysis. ICP-MS analysis of the MM-MOFs of Zn-Cu-BTC, Ni-Cu-BTC, Co-Cu-BTC, and Fe-Cu-BTC indicates that the metal exchange with respect to Cu2+ metal ions was 15%, 20%, 17%, and 12%; respectively. The ICP-MS data demonstrate that MM-MOFs contains partially exchanged metal ions from the parent MOF. Although the starting molar ratio of the metal ion is the same for all MOFs, it was observed that Ni2+ has the highest replacement percentage compared to the other metal ions. This difference in replacement ratio can be explained by the fact that replacement of metal ions is strongly dependent on the solubility of metal nitrates, reactivity, ionic radius of metal ion, and the pH of the reaction mixture.12

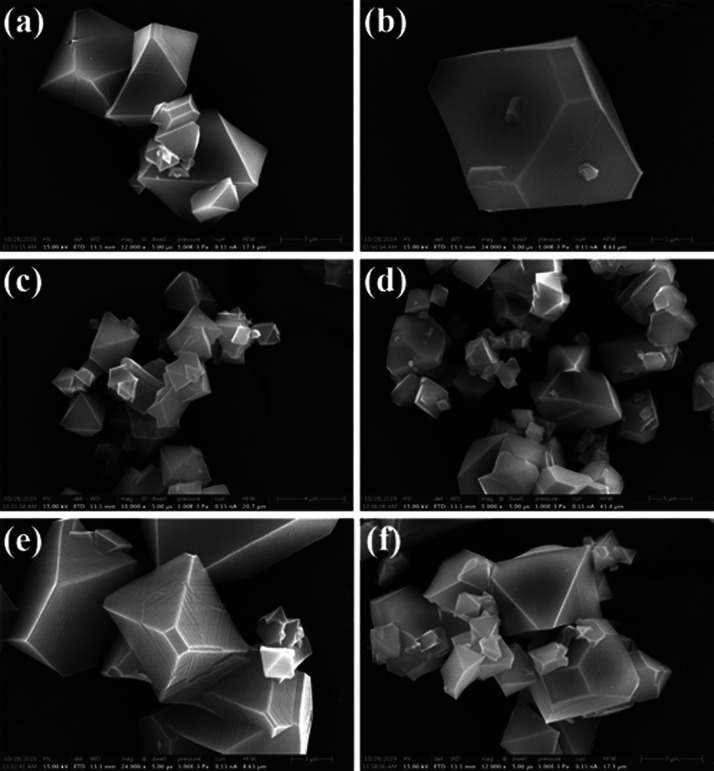

SEM images (Figure 5) display the growth of crystalline materials as expected. The SEM analysis also excludes the probability of contamination or growth of another phase during the metal exchange. Cu-BTC is displayed with polyhedral (octahedral) particles with sizes of 1–5 μm (Figure 5a,b). As a prototype, the SEM images of Ni(II) and Co2+ exchanged MOFs have been investigated to compare its morphology with that of the parent MOF. The images of Co-Cu-BTC (Figure 5c,d) and Ni-Cu-BTC (Figure 5e,f) show the same polyhedral particles with average sizes in the range of 1–5 μm without any amorphous phases. The SEM images also display homogeneous nanocrystallites without the existence of any other morphology. The crystallite size was estimated from the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the XRD peaks using Scherrer’s equation, as shown in Table 1. The exchange of metal ions was also quantified by SEM–EDX analysis. The distribution of metal ions was assessed by EDS analysis. The mapping data of Zn-Cu-BTC are shown in Figure S1. The EDS mapping of the Zn element shows that the Zn2+ are distributed in the area of crystalline particles. This clearly proves the existence of exchanged metals in the microcrystalline sample. The EDX elemental map of Zn-Cu-BTC verified that indeed they consist of Zn2+ ions ∼14% concerning Cu2+ ions (Figure S2). The mapping data of Fe-Cu-BTC is shown in Figure S3. The SEM image and EDS mapping of micrometer crystal particles for Fe-Cu-BTC show the presence of Fe metal in the crystalline sample. The EDX elemental map of Fe-Cu-BTC also proved that they certainly contain Fe2+ ions ∼10% for Cu2+ ions (Figure S4).

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of (a, b) Cu-BTC, (c, d) Co-Cu-BTC, and (e, f) Ni-Cu-BTC.

Table 1. BET Surface Area, Pore Parameters, and Crystallite Size of Cu-BTC Samples.

| MOFs | BET surface area (m2/g) | Langmuir surface area (m2/g) | micropore volume (cm3/g) | average pore diameter (nm) | crystallite size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-BTC | 945 | 1132 | 0.404 | 1.709 | 79 |

| Ni-Cu-BTC | 828 | 879 | 0.311 | 1.503 | 64 |

| Zn-Cu-BTC | 938 | 1055 | 0.376 | 1.603 | 53 |

| Fe-Cu-BTC | 820 | 980 | 0.350 | 1.708 | 65 |

| Co-Cu-BTC | 822 | 907 | 0.319 | 1.553 | 91 |

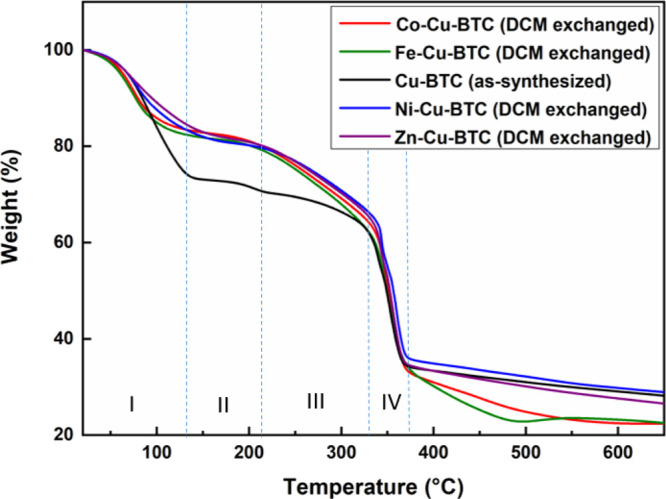

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) analysis was conducted on the as-synthesized Cu-BTC as well as the DCM exchanged MM-Cu-BTC (Figure 6). TGA measurements of the samples after an exchange in DCM are consistent with the noticeable weight loss of reported Cu-BTC.20 The initial weight loss (stage I) in all samples is due to the loss of physically adsorbed water molecules. A similar behavior was observed for all metal exchanged samples in which the weight loss was about 18%. However, the as-synthesized Cu-BTC lost about 27% of its weight when the temperature reached 125 °C. This result may be due to the fact that it has the highest surface area and pore volume (Table 1). In stage II (between 125 and 210 °C), a little weight loss was observed for all samples corresponding to the solvent that is physically adsorbed in internal pores.30 When the temperature reached about 200 °C, the structure started to lose the chemically bonded water, which needs a higher temperature than the physically adsorbed water to be released. In stage IV, all samples started to collapse when the temperature was increased further to about 330 °C due to backbone cleavage of the polymer (carbonation) and lost about 30% of its weight. The lattice disorder created due to the incorporation of the new metal cations may diversify the stability of the MM-MOFs.

Figure 6.

TGA analysis of Cu-BTC (as-synthesized) and MM-Cu-BTC (DCM exchanged).

Surface Area and Hydrogen Adsorption of Cu-BTC and MM-Cu-BTC

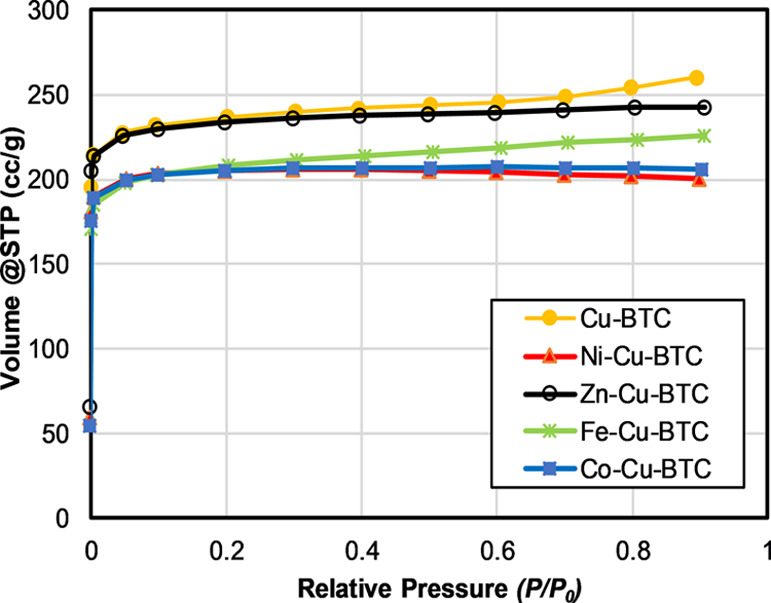

Figure 7 shows the nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K for Cu-BTC and MM-Cu-BTC samples. A steep curvature of the adsorption isotherm was observed at the low-pressure region after which the isotherm reached a plateau, indicating that equilibrium was reached and the adsorption is limited to the completion of a single monolayer. This shape is classified as Type-I according to the IUPAC31 and usually observed in microporous materials with pore size not much larger than the adsorbate size. The average pore size of Cu-BTC and all MM-Cu-BTC samples suggests that the prepared samples are microporous materials. The BET surface area and pore parameters obtained for Cu-BTC and the metal exchanged samples are given in Table 1. Cu-BTC obtained the highest surface area (945 m2/g) and pore volume (0.404 cm3/g). The high gas uptake indicates that activation and degassing were able to remove the guest molecules from the pores. The reported surface area in the open literature is ranging from 400 to 2000 m2/g, while most of the data is between 700 and 1000 m2/g.32 Yaghi and co-workers reported an apparent BET surface area of 1944 m2/g, which is in the high end of the aforementioned range.25 In this study, the surface area and pore volume were reduced after the incorporation of the second metal ions in the unsaturated metal centers. This issue may due to incomplete activation21 or the degradation in textural properties after the metal exchange. The loss in surface area may be due to the collapsed pores after exchange of metal ions12 or the adsorption of metal ions on the surface and within the pores. The higher loading intensifies the degradation or collapsing of pores compared to the lower loading.

Figure 7.

Nitrogen adsorption isotherm at 77 K of Cu-BTC and MM-Cu-BTC.

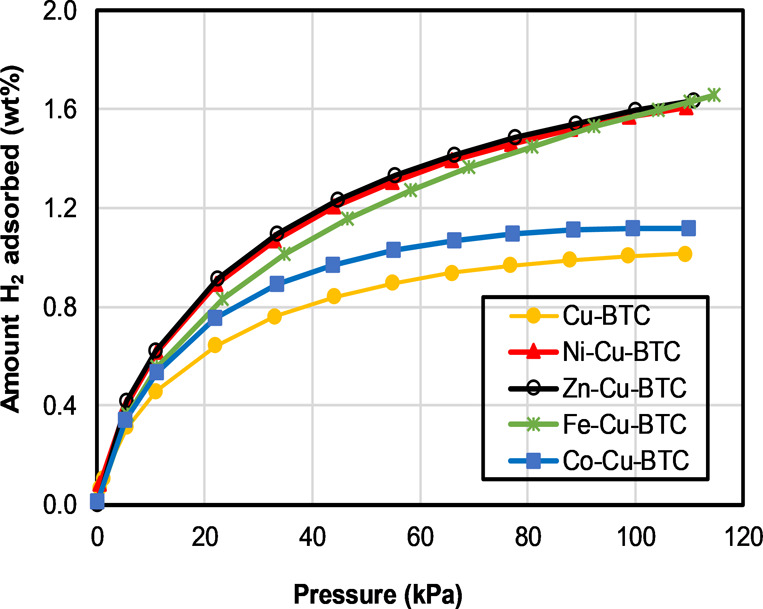

To investigate the hydrogen storage properties of Cu-BTC samples, low-pressure H2 isotherms were measured at 77 K, as shown in Figure 8 and Table 2. As expected, considerable amounts of hydrogen were adsorbed on the synthesized material because of their large porosities. It seems from Figure 8 that hydrogen adsorption almost reached saturation in the Cu-BTC sample with a gravimetric hydrogen capacity of 1.02 wt %. The adsorption isotherm of hydrogen on Co-Cu-BTC also reached saturation, however, with a higher adsorption capacity of 1.12 wt%, which represents about a 10% increase. On the other hand, the metal exchanged materials Ni-Cu-BTC, Zn-Cu-BTC, and Fe-Cu-BTC have a gravimetric hydrogen uptake of 1.61, 1.63, and 1.63 wt %, respectively. The increase in hydrogen adsorption capacity for the three metal exchanged materials is about 60% relative to that of the parent MOF (Cu-BTC). The improvement of gravimetric uptake in M-Cu-BTC (where M = Ni2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+) is probably due to the increase in binding enthalpy of H2 with the unsaturated metal sites after the partial exchange from Cu2+ to other metal ions. The higher charge density of metal ions strongly polarizes hydrogen and provides the primary binding sites inside the pores of Cu-BTC and subsequently enhances the gravimetric uptake of hydrogen. The performance of the material cycle was investigated using Ni-Cu-BTC as a prototype to verify the stability of MM-MOFs using gas adsorption. Both BET measurement and hydrogen adsorption studies indicate that the MM-MOFs do not lose its stability significantly, as shown in Figures S10 and S11. PXRD also verified the stability of the MM-MOF materials after gas adsorption. PXRD indicates that all the MM-MOFs are very stable even after hydrogen adsorption. The PXRD patterns of the samples after hydrogen adsorption are shown in Figure S12. They are in well agreement with the simulated PXRD pattern of Cu-BTC. The parent Cu-BTC structure was found to have a higher degree of crystallinity after gas adsorption in comparison to MM-MOFs.

Figure 8.

Hydrogen adsorption isotherm at 77 K of Cu-BTC and MM-Cu-BTC.

Table 2. Gravimetric Hydrogen Adsorption of Cu-BTC Samples at 77 K and 110 kPa.

| MOFs | total H2 gravimetric capacity (wt %) | Increase in Hydrogen capacitya (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cu-BTC | 1.02 | |

| Ni-Cu-BTC | 1.61 | 57.8 |

| Zn-Cu-BTC | 1.63 | 59.8 |

| Fe-Cu-BTC | 1.63 | 59.8 |

| Co-Cu-BTC | 1.12 | 9.8 |

Relative to the parent MOF (Cu-BTC).

Conclusions

A series of isostructural MM-MOFs of BTC [M-Cu-BTC, where M = Zn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Fe2+] have been synthesized using the post-synthetic exchange (PSE) method. The metal exchanged materials Ni-Cu-BTC, Zn-Cu-BTC, Fe-Cu-BTC, and Co-Cu-BTC showed an increase in the gravimetric hydrogen uptake of 57.8%, 59.8%, 58.9%, and 9.8%, respectively. The improvement of gravimetric uptake in MM-MOFs is probably due to the increase in the binding enthalpy of H2 with the unsaturated metal sites after the partial exchange. The binding enthalpy increases due to the higher charge density of the metal ions, and the unsaturated metal sites strongly polarize H2, which provides the primary binding sites for H2 inside the pores of Cu-BTC and subsequently enhances the gravimetric uptake of the materials. The synthetic strategy of MM-MOFs provides a way of improving gravimetric H2 storage capacities of known MOFs.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

Metal nitrates, 1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid linker, dimethylformamide (DMF), and dichloromethane (DCM) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co, Ltd. All reagents were used as purchased without further purification.

Powder X-ray diffraction data were collected using a Rigaku Miniflex II diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source. Data were acquired over the 2θ range between 3° and 50°. Quattro ESEM imaged MOF crystals. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on a TA SDT 2960 thermal analyzer. The samples were ground right before TGA experiments to minimize exposure to moisture. About 3–5 mg of each sample was heated to 600 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min under a nitrogen flow of 50 mL/min.

Synthesis of MOFs

Synthesis of Cu-BTC

Cu-BTC was synthesized as reported earlier.23 The solvent was decanted, and the remaining solid washed nine times with dichloromethane (DCM), each time letting the solid soak in dichloromethane (DCM) for 8 h.

Post-Synthetic Exchange (PSE)

M-Cu-BTC was prepared using the PSE method. Many portions of as-synthesized Cu-BTC crystals were soaked in 0.5 M DMF solutions of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, Co(NO3)2·6H2O, and FeCl2·6H2O three times at room temperature for 3 days. At the end of soaking, solutions of metal ions were decanted, and the transmetalated crystals of M-Cu-BTC were harvested by filtration. MM-MOF crystals were washed thoroughly with DMF several times and then soaked in DMF for complete removal of residual metal ions. The resulting cation-exchanged MOFs were activated with dichloromethane (DCM) nine times, each time letting the solid soak in DCM for 8 h.

Measurement of Gas Adsorption Isotherms

About 50 mg was degased at 150 °C for at least 10 h, and then the sample cell was weighted and mounted on the analysis station of Quantachrome Autosorb IQ-C-MP to measure the adsorption isotherms at a liquid nitrogen temperature of 77 K. The surface area was calculated using the built-in functions of ASiQwin 5.21 software provided by Quantachrome. The micropore area and volume were determined using the t-plot method. The quenched solid density functional theory (QSDFT) method with slit/cylindrical pores was used to obtain the pore size distribution. In the hydrogen adsorption measurements, high-purity hydrogen (99.9995%) was used. The regulator and pipes were flushed with hydrogen before connecting to the analyzer. The temperature was maintained at 77 K with liquid nitrogen throughout all measurements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology for funding this work through NSTIP project no. 14-ENE2278-04.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02810.

SEM–EDX analysis, TGA analysis, BET measurement after cyclic adsorption/desorption of hydrogen, PXRD after hydrogen adsorption, H2 adsorption data, and pore size distribution (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abdalla A. M.; Hossain S.; Nisfindy O. B.; Azad A. T.; Dawood M.; Azad A. K. Hydrogen Production, Storage, Transportation, and Key Challenges with Applications: A Review. Energy Convers. Manage. 2018, 165, 602–627. 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.03.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basile A.; Iulianelli A.. Advances in Hydrogen Production, Storage and Distribution; 2014, 10.1016/C2013-0-16359-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- US DOE . Technical System Targets: Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Light-Duty Fuel Cell Vehicles; 2020.

- Broom D. P.; Webb C. J.; Hurst K. E.; Parilla P. A.; Gennett T.; Brown C. M.; Zacharia R.; Tylianakis E.; Klontzas E.; Froudakis G. E.; et al. Outlook and Challenges for Hydrogen Storage in Nanoporous Materials. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 2016, 122, 1–21. 10.1007/s00339-016-9651-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. L.; Xu Q. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Platforms for Clean Energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1656–1683. 10.1039/c3ee40507a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J. Y.; Li C.; Li F. L.; Gu H. W.; Braunstein P.; Lang J. P. Recent Advances in Pristine Tri-Metallic Metal-Organic Frameworks toward the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Nanoscale 2020, 4816–4825. 10.1039/c9nr10109h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirscher M.; Panella B.; Schmitz B. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Hydrogen Storage. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 129, 335–339. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Wang K.; Sun Y.; Lollar C. T.; Li J.; Zhou H. C. Recent Advances in Gas Storage and Separation Using Metal-Organic Frameworks. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 108–121. 10.1016/j.mattod.2017.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L.; Zhou H. C.. Hydrogen Storage in Metal-Organic Frameworks. In Nanostructured Materials for Next-Generation Energy Storage and Conversion: Hydrogen Production, Storage, and Utilization; 2017; pp. 143–170, 10.1007/978-3-662-53514-1_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Chen F.; Li B.; Qian G.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks for Fuel Storage. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 373, 167–198. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S.; Feng L.; Wang K.; Pang J.; Bosch M.; Lollar C.; Sun Y.; Qin J.; Yang X.; Zhang P.; et al. Stable Metal-Organic Frameworks: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704303. 10.1002/adma.201704303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek C. K.; Dincǎ M. Cation Exchange at the Secondary Building Units of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5456–5467. 10.1039/c4cs00002a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dincǎ M.; Long J. R. High-Enthalpy Hydrogen Adsorption in Cation-Exchanged Variants of the Microporous Metal-Organic Framework Mn3[(Mn4CI)3(BTT)8(CH3OH)10]2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11172–11176. 10.1021/ja072871f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abednatanzi S.; Gohari Derakhshandeh P.; Depauw H.; Coudert F. X.; Vrielinck H.; Van Der Voort P.; Leus K. Mixed-Metal Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 2535–2565. 10.1039/c8cs00337h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh M. P.; Park H. J.; Prasad T. K.; Lim D. W. Hydrogen Storage in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 782–835. 10.1021/cr200274s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.; Wu J.; Wang J.; Fan Y.; Zhang S.; Ma N.; Dai W. Highly Efficient Capture of Benzothiophene with a Novel Water-Resistant-Bimetallic Cu-ZIF-8 Material. Inorganica. Chim. Acta. 2020, 503, 119412–119419. 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Li X.; Dai W.; Fang Y.; Huang H. Enhanced Adsorption of Dibenzothiophene with Zinc/Copper-based Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 21044–21050. 10.1039/C5TA05204A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vitillo J. G.; Regli L.; Chavan S.; Ricchiardi G.; Spoto G.; Dietzel P. D. C.; Bordiga S.; Zecchina A. Role of Exposed Metal Sites in Hydrogen Storage in MOFs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8386–8396. 10.1021/ja8007159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.; Cahill J. F.; Fei H.; Prather K. A.; Cohen S. M. Postsynthetic Ligand and Cation Exchange in Robust Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18082–18088. 10.1021/ja3079219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui S. S.-Y.; Lo S. M.-F.; Charmant J. P. H.; Orpen A. G.; Williams I. D. A Chemically Functionalizable Nanoporous Material [Cu3(TMA)2(H2O)3](N). Science 1999, 283, 1148–1150. 10.1126/science.283.5405.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K. S.; Adhikari A. K.; Ku C. N.; Chiang C. L.; Kuo H. Synthesis and Characterization of Porous HKUST-1 Metal-Organic Frameworks for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 13865–13871. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.04.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gul-E-Noor F.; Jee B.; Mendt M.; Himsl D.; Pöppl A.; Hartmann M.; Haase J.; Krautscheid H.; Bertmer M. Formation of Mixed Metal Cu3–xZnx(btc)2 Frameworks with Different Zinc Contents: Incorporation of Zn2+ into the Metal-Organic Framework Structure as Studied by Solid-State NMR. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 20866–20873. 10.1021/jp3054857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peedikakkal A. M. P.; Jimoh A. A.; Shaikh M. N.; Ali B. E. Mixed-Metal Metal-Organic Frameworks as Catalysts for Liquid-Phase Oxidation of Toluene and Cycloalkanes. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 4383–4390. 10.1007/s13369-017-2452-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gotthardt M. A.; Schoch R.; Wolf S.; Bauer M.; Kleist W. Synthesis and Characterization of Bimetallic Metal-Organic Framework Cu-Ru-BTC with HKUST-1 Structure. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2052–2056. 10.1039/c4dt02491e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Foy A. G.; Matzger A. J.; Yaghi O. M. Exceptional H2 Saturation Uptake in Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3494–3495. 10.1021/ja058213h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G.; Rai R. K.; Tyagi D.; Yao X.; Li P. Z.; Yang X. C.; Zhao Y.; Xu Q.; Singh S. K. Room-Temperature Synthesis of Bimetallic Co-Zn Based Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks in Water for Enhanced CO2 and H2 Uptakes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 14932–14938. 10.1039/c6ta04342a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapelewski M. T.; Runčevski T.; Tarver J. D.; Jiang H. Z. H.; Hurst K. E.; Parilla P. A.; Ayala A.; Gennett T.; Fitzgerald S. A.; Brown C. M.; et al. Record High Hydrogen Storage Capacity in the Metal-Organic Framework Ni2(m-Dobdc) at Near-Ambient Temperatures. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 8179–8189. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b03276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapelewski M. T.; Geier S. J.; Hudson M. R.; Stück D.; Mason J. A.; Nelson J. N.; Xiao D. J.; Hulvey Z.; Gilmour E.; Fitzgerald S. A.; et al. M2(m-Dobdc) (M = Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni) Metal-Organic Frameworks Exhibiting Increased Charge Density and Enhanced H2 Binding at the Open Metal Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12119–12129. 10.1021/ja506230r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- S̆imȧnas M.; Jee B.; Hartmann M.; Banys J.; Pöppl A. Adsorption and Desorption of HD on the Metal-Organic Framework Cu2.97Zn0.03(Btc)2 Studied by Three-Pulse ESEEM Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 28530–28535. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b11058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichte K.; Kratzke T.; Kaskel S. Improved Synthesis, Thermal Stability and Catalytic Properties of the Metal-Organic Framework Compound Cu3(BTC)2. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2004, 73, 81–88. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2003.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S.; Jiang X.; Ruan L. W.; Liu B.; Wang Y. M.; Zhu J. F.; Qiu L. G. Post-Combustion CO2 Capture with the HKUST-1 and MIL-101(Cr) Metal-Organic Frameworks: Adsorption, Separation and Regeneration Investigations. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 179, 191–197. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Mu X.; Lester E.; Wu T. High-Efficiency Synthesis of HKUST-1 under Mild Conditions with High BET Surface Area and CO2 Uptake Capacity. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2018, 28, 584–589. 10.1016/j.pnsc.2018.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.