Abstract

The phonon transport properties of CuSCN and CuSeCN have been investigated using the density functional theory and semiclassical Boltzmann transport theory. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional shows an indirect (direct) electronic band gap of 2.18 eV (1.80 eV) for CuSCN (CuSeCN). The calculated phonon band structure shows that both compounds are dynamically stable. The Debye temperature of the acoustic phonons is 122 and 107 K for CuSCN and CuSeCN, respectively. The extended in-plane bond lengths as compared to the out-of-plane bond lengths result in phonon softening and hence, low lattice thermal conductivity. The calculated room temperature in-plane (out-of-plane) lattice thermal conductivity of CuSCN and CuSeCN is 2.39 W/mK (4.51 W/mK) and 1.70 W/mK (3.83 W/mK), respectively. The high phonon scattering rates in CuSeCN give rise to in-plane low lattice thermal conductivities. The room-temperature Grüneisen parameters of CuSCN and CuSeCN are found to be 0.98 and 1.08, respectively.

Introduction

Copper thiocyanate (CuSCN) and copper selenocyanate (CuSeCN), inorganic compounds of the metal pseudohalide family, exhibit remarkably high optical transparency with a significant hole mobility of 0.01–0.1 cm2 V−1 s−1 and high chemical stability.1 Therefore, these materials are the principal candidate for a wide range of applications in thin-film transistors2 and solar cells.3−5 Moreover, CuSCN, being a solution-processing material at room temperature,6 can be an ideal material for an inexpensive, large-area, and flexible substrate. In addition, thin-film CuSCN is almost free of pinholes and defects, which is attributed to its polymeric nature.7 Furthermore, CuSeCN is structurally similar to CuSCN and has recently been synthesized from solution processing with emphases on its applications in organic photovoltaics and light-emitting diodes.8

CuSCN and CuSeCN have been experimentally synthesized in orthorhombic (α) and hexagonal (β) phases, but the hexagonal phase is energetically more favorable by an amount of 5210 and 34 meV8 per formula unit, respectively. CuSCN and CuSeCN are intrinsically p-type materials, and the Cu vacancies further enhance the hole transport characteristics by placing the Fermi level into the valence band near its maxima.8,10,11 They have applications as a potential hole-transport layer in a solar cell for a variety of active absorber layers such as small molecules, polymers, silicon, and hybrid perovskites4,8,12,13 because of having favorable energy positions of the orbitals. The band structure, bonding characteristics, and native defects of bulk β-CuSCN have been investigated by first-principles calculations.14 X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Raman and optical spectroscopy, and atomic force microscopy, together with scanning and transmission electron microscopy, have been employed to study the structural characterization of CuSCN thin films and nanowires.15 A fundamental understanding of phonon dynamics and phonon transport, especially for CuSeCN, is still missing in the literature, despite its technological relevance as the hole-transport layer in photovoltaic devices. In this work, we have investigated the thermoelectric coefficients and lattice thermal conductivity by employing the density functional theory (DFT) and semiclassical Boltzmann transport theory to overcome this gap.

Computational Methods

The Quantum Espresso Package,16 within the framework of DFT, is used to perform the electronic structure calculations. The exchange–correlation potential is treated with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) flavor of generalized gradient approximation, the cutoff energy is set to 50 Ry, and k-mesh 12 × 12 × 4 (36 × 36 × 12) is used for self-consistent (non-self-consistent) calculations. The structural relaxation is considered to be achieved unless the Hellmann–Feynman forces are dropped below 10–4 Ry/bohr for all atoms. The electronic transport properties are calculated by the semiclassical Boltzmann transport approach, as implemented in BoltzTraP2.17 To obtain the phonon band dispersion and the lattice thermal conductivity, we calculate the harmonic force constants using the density functional perturbation theory, as implemented in Quantum Espresso16 with a q-point grid size of 8 × 8 × 8. In calculating the third-order interatomic force constants, two atoms up to the eighth nearest neighbors are displaced. The lattice contributions of the thermal transport (phonon contribution) are calculated using the ShengBTE code,18 which solves the Boltzmann transport equation. A deviation of less than 2% is observed in the lattice thermal conductivities at 300 K when the seventh instead of eighth nearest neighbor displacement is considered. The well-converged lattice thermal conductivities are calculated with a dense q-mesh 40 × 40 × 14.

Results and Discussion

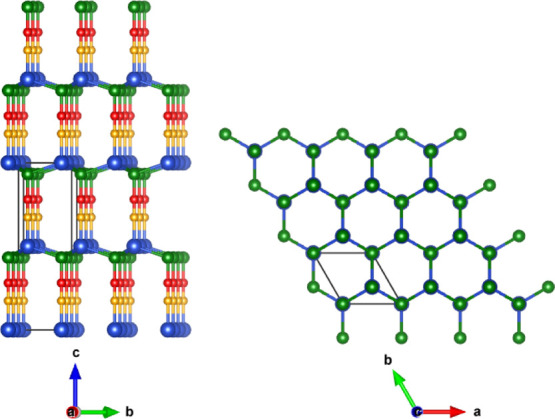

The crystal structures of hexagonal experimental β-phase (space-group-P63mc) of CuSCN and CuSeCN have been optimized, and it was found that the computed lattice parameters are well in agreement with the previous reports (Table 1). Table 1 shows that the triple covalent N≡C bond is the shortest one, followed by the covalent C–S/Se bond, weak dative Cu–N bond, and the mixed ionic–covalent Cu–S/Se bond. Figure 1 shows the crystal structure of CuXCN (X = S and Se), where CNX units are parallel to each other in the out-of-plane direction. The CuXCN networks extend in-plane and out-of-plane directions through tetrahedrane coordination of each Cu atom with three X atoms and one N atom.

Table 1. Calculated Lattice Constants (a, c), Bond Lengths (N–C, C–X, Cu–X, and Cu–N), Electronic Band Gaps (Eg), Cutoff Frequencies (ω0), and Debye Temperatures (θD) of Acoustic Phonons.

Figure 1.

Optimized crystal structure of CuXCN (X = S and Se). The blue, green, red, and orange spheres represent Cu, X, C, and N atoms, respectively. A bulk unit cell is enclosed in the black lines.

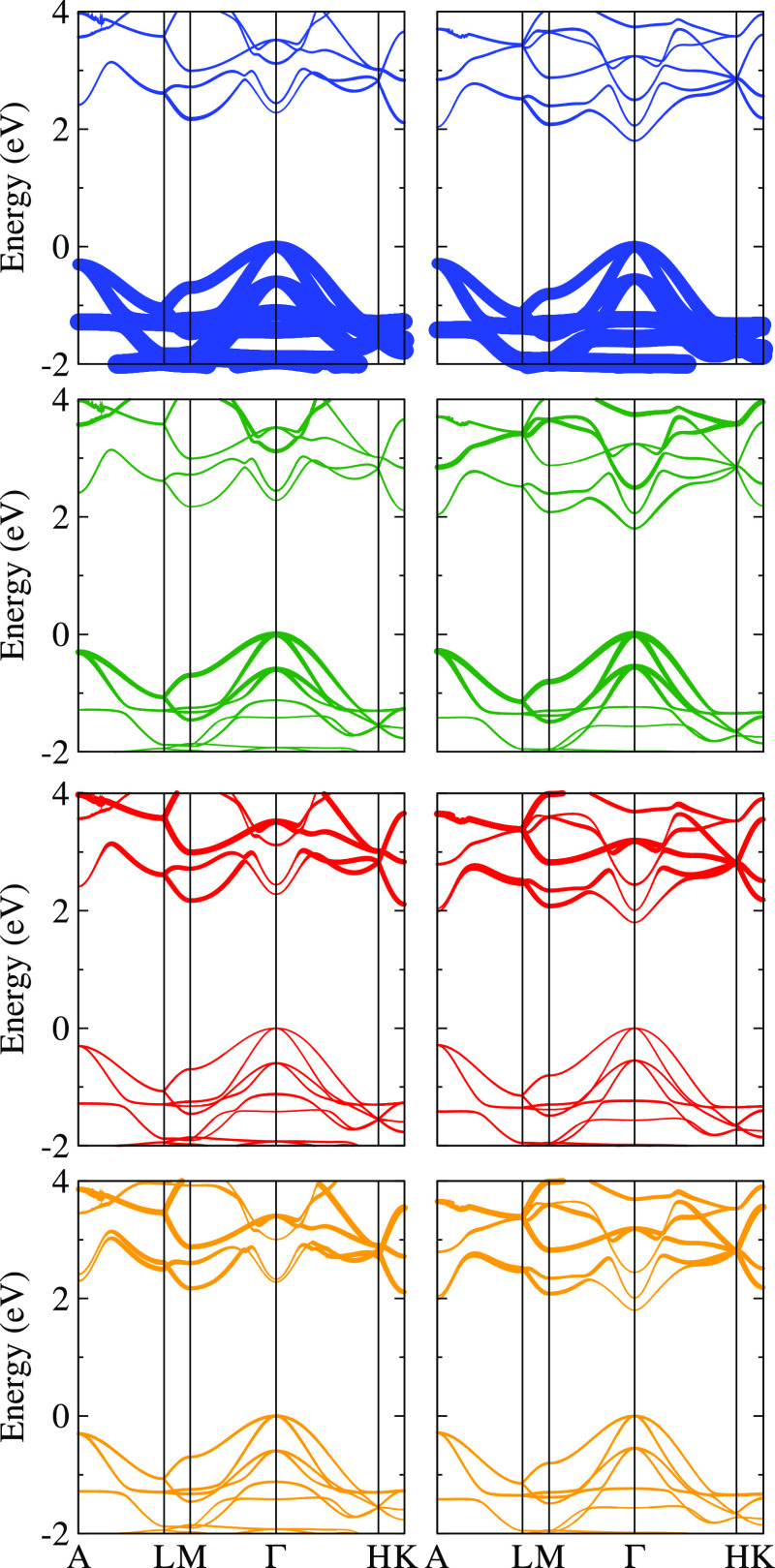

Figure 2 illustrates the electronic features of CuXCN (X = S and Se) in terms of the orbital-resolved band structures obtained along with the high symmetry points A (0, 0, 1/2), L (1/2, 1/2, 0), M (1/2, 0, 0), G (0, 0, 0), H (1/3, 1/3, 1/2), and K (1/3, 1/3, 0). The dominant contribution around the valence band maximum arises from the Cu d states, followed by the X p states. The dominant character of Cu d states in the valence band uncovers the origin of enhanced hole conductivity in Cu-deficient thiocyanate, where Cu vacancy would place the X p states to higher energy as compared to the pristine CuXCN. There is a negligible contribution from C p and N p states because of the strong N–C covalent bonding that keeps their electrons tightly bound. In the case of CuSCN, the N p states and the C p states contribute equally around the conduction band minimum, whereas the Cu d states add a small contribution. For CuSeCN, the Se p states construct the conduction band minimum and push it down at the Γ point, resulting in a direct band gap. The direct band gap in CuSeCN may be attributed to the widespread nature of Se p orbitals as compared to S p orbitals in CuSCN.

Figure 2.

Orbital-resolved (Cu d states: blue, X p states: green, C-p states: red, and N p states: orange) electronic band structure of CuSCN (first column) and CuSeCN (second column).

It is well known for the PBE functional9 that the calculated band gap of 2.13 eV (CuSCN) and 1.81 eV (CuSeCN) are underestimated as compared with the experimental values of 3.60 eV (CuSCN)10 and 3.53 eV (CuSeCN).8 However, these values are in agreement with the previous theoretical reports (see Table 1). At 300 K, the calculated electrical conductivity (σ), Seebeck coefficient (S), and electronic thermal conductivity (κe) as a function of chemical potential (μ) are given in Supporting Information (see Figure S1). We used the same value of relaxation time (5 fs) as employed earlier for CuSCN.20 The extension of μ on either side of 0 eV corresponds to the hole (positive scale) and electron (negative scale) concentrations. The obtained results for CuSCN are similar to those of the previous study.20 For example, the room-temperature peak value of S for CuSCN turns out to be 1.58 mV/K, which finds a fair agreement with that reported (1.60 mV/K) in ref (20). The corresponding S value is found to be 1.55 mV/K for CuSeCN. It is worth mentioning here that both compounds investigated in this study have S values significantly larger than 0.53 mV/K for SnSe21 and 0.4 mV/K for PbTe22 at 300 K. It implies that CuSCN and CuSeCN could find their potential in thermoelectrics. Because both compounds have closely comparable electronic transports, phonon transports, which are the primary focus of this work, are necessary to predict a better thermoelectric candidate.

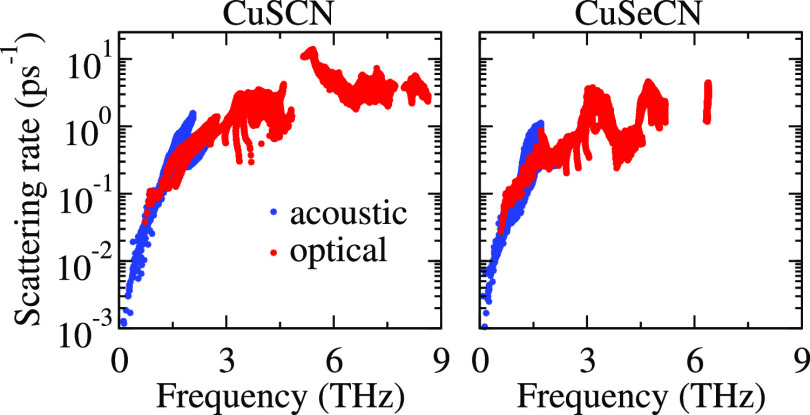

The calculated phonon band dispersion of CuXCN (X = S and Se) is shown in Figure 3. The positive phonon frequencies in the entire Brillouin zone guarantee the dynamic stability of the optimized structures. Although the phonon band dispersions are similar, including the phonon frequency span, the cutoff frequencies of acoustic phonons are 2.54 and 2.23 THz for CuSCN and CuSeCN, respectively. Because the acoustic modes have a primary influence on heat conduction through lattice vibrations, CuSeCN may exhibit lower lattice thermal conductivity (κl) than CuSCN. A frequency gap of 0.32 THz around 5 THz for CuSCN, as observed in ref (20), elongates the phonon relaxation time because of the reduced number of scattering channels and leads to larger κl, whereas this character has vanished in CuSeCN. It may be attributed to Se’s sizeable atomic mass, which decreases phonon frequency to the same as observed for MX2 (M = Mo, W; X = S, Se, Te).23 Although the highest phonon frequencies are comparable, the phonon modes below 25 THz are significantly suppressed, and the frequency gap vanishes. Unlike CuSCN, CuSeCN acquires the vigorous mixing of acoustic and optical phonons, resulting in high phonon scattering rates and flat phonon modes, yielding small phonon group velocities and hence low κl.

Figure 3.

Calculated phonon dispersions of CuSCN and CuSeCN.

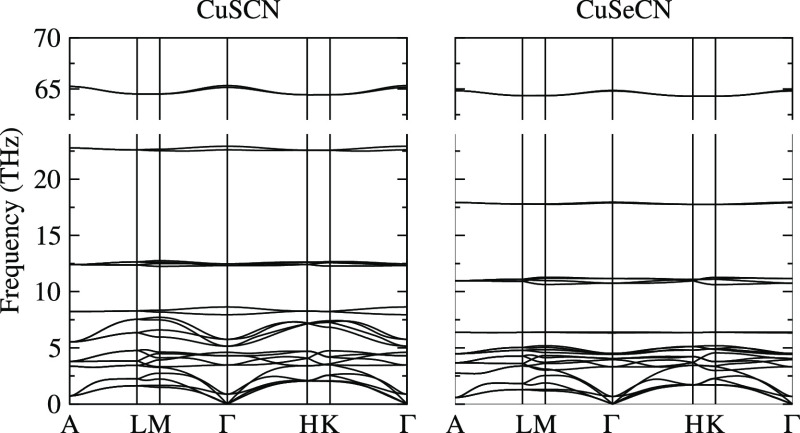

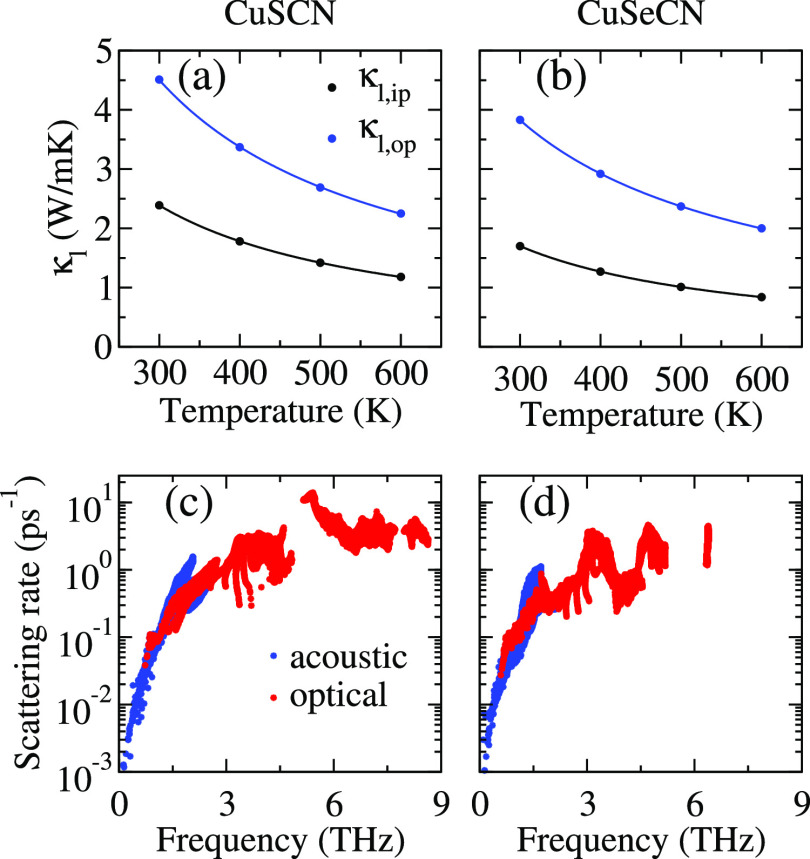

To accomplish high performance in thermoelectric materials, a value of κl < 2 W/mK is promising.24Figure 4 demonstrates the temperature-dependent in-plane (κl,ip) and out-of-plane (κl,op) lattice thermal conductivity of CuSCN and CuSeCN. The calculated room temperature in-plane (out-of-plane) lattice thermal conductivity of CuSCN and CuSeCN is 2.39 W/mK (4.51 W/mK) and 1.70 W/mK (3.83 W/mK), respectively. Our calculated lattice thermal conductivity (2.39 Wm/K) of β-CuSCN is close to the recently published value (2.40 Wm/K) in ref (20). It should be noted that the calculated lattice thermal conductivity (1.70 Wm/K) of CuSeCN is 1.4 times lower than CuSCN. By having comparable electronic transport coefficients but lower lattice thermal conductivity, CuSeCN could be a better choice over CuSCN in thermoelectrics. We have obtained the lowest κl,ip (κl,op) values, for example 1.18 W/mK (2.25 W/mK) for CuSCN and 0.84 W/mK (2.00 W/mK) for CuSeCN at 600 K. There exists a strong anisotropy in κl,ip and κl,op throughout the temperature range considered in this work. This may be because of the bonding features drawn from the electron localization function (ELF) profiles in Figure 5. In the out-of-plane direction, a strong bonding exists because of the sharing of electrons in the NCX-unit [see ELF(100)], which nurtures phonon hardening and consequently enlarges κl,op. On the other hand, relatively weak Cu–X bonding is obvious from ELF(001), leading to phonon softening, which suppresses κl,ip. It is also well understandable from the bond lengths, which are extended in-plane as compared to out-of-plane. CuSeCN outperforms CuSCN in terms of its low lattice thermal conductivity, and it is attributed to the low Debye temperatures for acoustic phonons (see Table 1).25

Figure 4.

Calculated lattice thermal conductivity and phonon scattering rate of CuSCN (a,c) and CuSeCN (b,d), respectively.

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional ELF profile of CuSCN and CuSeCN. The profile is cut through (001) and (100) planes (see the topmost panel).

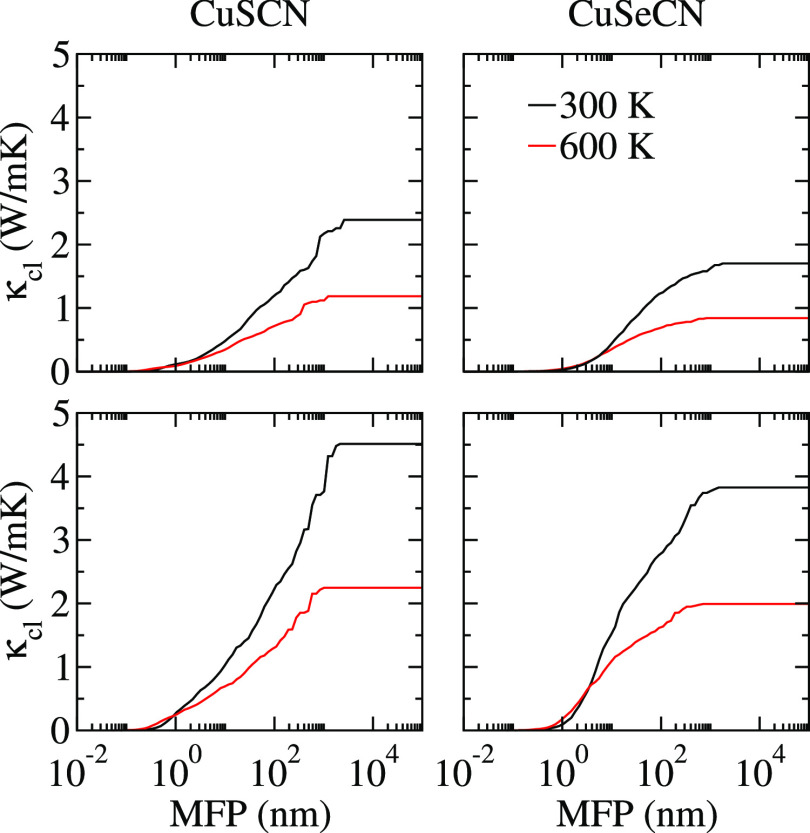

We calculated the Debye temperature (θD) using the relation θD = ℏω0/kB, where ℏ, ω0, and kB are referred to Planck constant, the maximum frequency of acoustic phonons, and Boltzmann constant, respectively. A high value of θD means higher magnitudes of acoustic phonon velocities, which suppress the process of phonon–phonon scattering owing to decreased phonon populations.26 In addition, Se atoms work as phonon rattlers because of their larger atomic size as compared to S atoms. Figure 4 shows the dependence of phonon scattering rates on the phonon frequency. The high phonon scattering rates, coupled with the mixing of acoustic and low-lying optical modes, result in low lattice thermal conductivity. This type of mode mixing depends on the atomic masses of the constituent elements and the bonds’ stiffness existing in the compound.23 As a consequence, frequent scatterings between acoustic and optical modes take place, resulting in suppression of the lattice thermal conductivity. These features are in line with the previous reports on thermoelectric materials with low thermal conductivities.27−31 For CuSeCN, abovementioned mixing of phonon modes takes place 0.59 THz lower than 0.73 THz for CuSCN, affecting the κl values that are suppressed in the former compound. Furthermore, the higher lattice anharmonicity of CuSeCN than CuSCN, as assured from its mode Grüneisen parameter 1.08 (0.98 for CuSCN) at room temperature, leads to low lattice thermal conductivity. To pave the way to the nanoengineering of materials, we address cumulative lattice thermal conductivity (κcl) as a function of phonon mean free path (MFP), as shown in Figure 6. In noncrystalline materials, such as nanowires and thin membranes, the phonons with smaller MFPs and wavelengths control κl because of excess surface phonon scatterings. κl keeps increasing with the ascending phonon MFP until it reaches the thermodynamic limit. The phonon MFPs corresponding to this limit are 2595 nm (2154 nm) and 1789 nm (1485 nm) for in-plane (out-of-plane) κl values of CuSCN and CuSeCN, respectively. The phonons having MFPs below 100 nm (30 nm) and 97 nm (15 nm) result in half of the total of κl,ip (κl,op) of CuSCN and CuSeCN, respectively, at room temperature. This indicates that one needs to prepare CuSeCN of a small thickness as compared to the CuSCN to avail the potential of nanostructuring to reduce κl,ip (κl,op). Such strategies have been experimentally employed earlier to reduce κl even by up to 90%, for example, for nanostructured silicon.32

Figure 6.

In-plane (first row) and out-of-plane (second row) cumulative lattice thermal conductivities of CuSCN and CuSeCN as a function of phonon MFP.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the thermal transport properties of CuSCN and CuSeCN have been investigated by DFT and semiclassical Boltzmann transport theory. The phonon band structure’s positive phonon frequencies reveal dynamic stability with intense mixing of acoustic and optical phonons along with the low cutoff frequencies of acoustic phonons (2.54 THz for CuSCN and 2.23 THz CuSeCN). Relatively flatter phonon modes result in low group velocities and hence, the low lattice thermal conductivity in CuSeCN. The two-dimensional ELF profiles suggest strong out-of-plane bonding as compared to the in-plane bonding, which leads to phonon hardening and larger thermal conductivities in a later direction. The calculated lattice thermal conductivities κl,ip and κl,op are 1.18 and 2.25 W/mK for CuSeCN and 0.84 and 2.00 W/mK for CuSCN at 600 K.

Acknowledgments

N.S. acknowledges the financial support by the Abu Dhabi Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK) under the AARE19-126 and support from the Khalifa University of Science and Technology.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03696.

Calculated electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, electronic thermal conductivity of CuSCN and CuSeCN as a function of chemical potential at 300 K along the in-plane and out-of-plane directions (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pattanasattayavong P.; Ndjawa G. O. N.; Zhao K.; Chou K. W.; Yaacobi-Gross N.; O’Regan B. C.; Amassian A.; Anthopoulos T. D. Electric Field-Induced Hole Transport in Copper(i) Thiocyanate (CuSCN) Thin-Films Processed From Solution at Room Temperature. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 4154. 10.1039/c2cc37065d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanasattayavong P.; Yaacobi-Gross N.; Zhao K.; Ndjawa G. O. N.; Li J.; Yan F.; O’Regan B. C.; Amassian A.; Anthopoulos T. D. Hole-Transporting Transistors and Circuits Based on the Transparent Inorganic Semiconductor Copper(I) Thiocyanate (CuSCN) Processed from Solution at Room Temperature. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 1504. 10.1002/adma.201202758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan B.; Schwartz D. T.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Grätzel M. Electrodeposited Nanocomposite n–p Heterojunctions for Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 1263.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P.; Tanaka S.; Ito S.; Tetreault N.; Manabe K.; Nishino H.; Nazeeruddin M. K.; Grätzel M. Inorganic Hole Conductor-Based Lead Halide Perovskite Solar Cells With 12.4% Conversion Efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3834. 10.1038/ncomms4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappaz-Gillot C.; Berson S.; Salazar R.; Lechêne B.; Aldakov D.; Delaye V.; Guillerez S.; Ivanova V. Polymer Solar Cells with Electrodeposited CuSCN Nanowires as New Efficient Hole Transporting Layer. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 120, 163. 10.1016/j.solmat.2013.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumara G. R. R. A.; Konno A.; Senadeera G. K. R.; Jayaweera P. V. V.; De Silva D. B. R. A.; Tennakone K. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell with the Hole Collector p-CuSCN Deposited From a Solution in n-Propyl Sulphide. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2001, 69, 195. 10.1016/s0927-0248(01)00027-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perera V. P. S.; Senevirathna M. K. I.; Pitigala P. K. D. D. P.; Tennakone K. Doping CuSCN Films for Enhancement of Conductivity: Application in Dye-Sensitized Solid-State Solar Cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2005, 86, 443. 10.1016/j.solmat.2004.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeyasinghe N.; Tsetseris L.; Regoutz A.; Sit W.-Y.; Fei Z.; Du T.; Wang X.; McLachlan M. A.; Vourlias G.; Patsalas P. A.; Payne D. J.; Heeney M.; Anthopoulos T. D. Copper (I) Selenocyanate (CuSeCN) as a Novel Hole-Transport Layer for Transistors, Organic Solar Cells, and Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1707319. 10.1002/adfm.201707319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Yang W.; Burke K.; Yang Z.; Gross E. K. U.; Scheffler M.; Scuseria G. E.; Henderson T. M.; Zhang I. Y.; Ruzsinszky A.; Peng H.; Sun J.; Trushin E.; Görling A. Understanding Band Gaps of Solids in Generalized Kohn–Sham Theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 2801. 10.1073/pnas.1621352114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennakone K.; Jayatissa A. H.; Fernando C. A. N.; Wickramanayake S.; Punchihewa S.; Weerasena L. K.; Premasiri W. D. R. Semiconducting and Photoelectrochemical Properties of n- and p-Type β-CuCNS. Phys. Status Solidi A 1987, 103, 491. 10.1002/pssa.2211030220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetseris L. Copper thiocyanate: Polytypes, Defects, Impurities, and Surfaces. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2016, 28, 295801. 10.1088/0953-8984/28/29/295801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaacobi-Gross N.; Treat N. D.; Pattanasattayavong P.; Faber H.; Perumal A. K.; Stingelin N.; Bradley D. D. C.; Stavrinou P. N.; Heeney M.; Anthopoulos T. D. High-Efficiency Organic Photovoltaic Cells Based on the Solution-Processable Hole Transporting Interlayer Copper Thiocyanate (CuSCN) as a Replacement for PEDOT:PSS. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401529. 10.1002/aenm.201401529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad M.; Singh N.; De Bastiani M.; De Wolf S.; Schwingenschlögl U. Copper Thiocyanate and Copper Selenocyanate Hole Transport Layers: Determination of Band Offsets with Silicon and Hybrid Perovskites from First Principles. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2019, 13, 1900328. 10.1002/pssr.201900328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe J. E.; Kaspar T. C.; Droubay T. C.; Varga T.; Bowden M. E.; Exarhos G. J. Electronic and Defect Structures of CuSCN. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 9111. 10.1021/jp101586q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldakov D.; Chappaz-Gillot C.; Salazar R.; Delaye V.; Welsby K. A.; Ivanova V.; Dunstan P. R. Properties of Electrodeposited CuSCN 2D Layers and Nanowires Influenced by Their Mixed Domain Structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 16095. 10.1021/jp412499f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giannozzi P.; Baroni S.; Bonini N.; Calandra M.; Car R.; Cavazzoni C.; et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A Modular and Open-Source Software Project for Quantum Simulations of Materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 395502. 10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen G. K. H.; Carrete J.; Verstraete M. J. BoltzTraP2, a program for interpolating band structures and calculating semi-classical transport coefficients. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2018, 231, 140. 10.1016/j.cpc.2018.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Carrete J.; A Katcho N.; Mingo N. ShengBTE: A Solver of the Boltzmann Transport Equation for Phonons. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 1747. 10.1016/j.cpc.2014.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. L.; Saunders V. I. The Structure And Polytypism of the β modification of copper(I) thiocyanate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1981, 37, 1807. 10.1107/s0567740881007309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y.; Wang F. Q.; Wang Q. Ultralow Thermal Conductivity and Negative Thermal Expansion of CuSCN. Nano Energy 2020, 73, 104822. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.-D.; Lo S.-H.; Zhang Y.; Sun H.; Tan G.; Uher C.; Wolverton C.; Dravid V. P.; Kanatzidis M. G. Ultralow Thermal Conductivity and High Thermoelectric Figure of Merit in SnSe Crystals. Nature 2014, 508, 373. 10.1038/nature13184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Zheng Y.; Zheng J.-C. Thermoelectric Transport Properties of PbTe Under Pressure. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2010, 82, 195102. 10.1103/physrevb.82.195102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.-F.; Zeng Z. Roles of Mass, Structure, and Bond Strength in the Phonon Properties and Lattice Anharmonicity of Single-Layer Mo and W Dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 18779. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b04669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tritt T. M.; Subramanian M. A. Thermoelectric Materials, Phenomena, and Applications: A Bird’s Eye View. MRS Bull. 2006, 31, 188. 10.1557/mrs2006.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziman J. M.Electrons and Phonons; Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay L.; Broido D. A.; Reinecke T. L. First-Principles Determination of Ultrahigh Thermal Conductivity of Boron Arsenide: A Competitor for Diamond?. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 025901. 10.1103/physrevlett.111.025901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding G.; Gao G. Y.; Huang Z.; Zhang W.; Yao K. Thermoelectric Properties of Monolayer MSe2 (M = Zr, Hf): Low Lattice Thermal Conductivity and a Promising Figure of Merit. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 375703. 10.1088/0957-4484/27/37/375703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.; Sun Q. Bi2O2Se Nanosheet: An Excellent High-Temperature n-Type Thermoelectric Material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 053901. 10.1063/1.5017217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad M.; Singh N.; Larsson J. A. Bulk and Monolayer Bismuth Oxyiodide (BiOI): Excellent High Temperature p-Type Thermoelectric Materials. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 075309. 10.1063/1.5133711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad M.; Singh N.; Sattar S.; De Wolf S.; Schwingenschlögl U. Ultralow Lattice Thermal Conductivity and Thermoelectric Properties of Monolayer Tl2O. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 3004. 10.1021/acsaem.9b00249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.; Singh N.; Schwingenschlögl U. Two-Dimensional Tellurene as Excellent Thermoelectric Material. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 1950. 10.1021/acsaem.8b00032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bux S. K.; Blair R. G.; Gogna P. K.; Lee H.; Chen G.; Dresselhaus M. S.; Kaner R. B.; Fleurial J.-P. Nanostructured Bulk Silicon as an Effective Thermoelectric Material. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 2445. 10.1002/adfm.200900250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.