Abstract

Wood pellet boilers for residential heating applications offer the promise of low emissions, high efficiency, and automatic operation. However, when operated in the field, these units operate often at very low loads causing them to cycle. In this study, the performance of a 25 kW modern pellet boiler under emulated field conditions and fixed nominal loads of 15 and 100% has been studied in a lab—with and without a buffer tank. A dilution tunnel approach was used for the measurement of particulate emissions, in accordance with US certification testing requirements under EPA Methods 28 WHH and 28 WHH PTS. Results show that increasing the amount of thermal storage used decreases cycling rates leading to decreased emissions and increased efficiency. Without thermal storage, integrated efficiency over a 15% load test period was 57%, compared to 74% when thermal storage was used. Particulate emissions were 180 and 64 mg/MJ for the 15% load case without and with thermal storage, respectively.

1. Introduction

There has been an increase in the use of wood products for heating in the United States (US), particularly in the Northeast, since 2005.1,2 The Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported in 2014 that 2.5 million households across the country use wood as a primary fuel and another 9 million households use wood as a secondary fuel. Much of this is cordwood, but wood pellet use in stove, hydronic heaters, and furnaces has been growing.

Of the fuels used, wood pellets typically have the lowest emissions.3,4 Pellets are drier, have a high surface-to-volume ratio, and can be fed into the combustion zone automatically in response to a heating load roughly like oil and gas fuels. Pellet-fired boilers currently available on the market typically have the ability to modulate the firing rate to 30% of the maximum. In residential applications, this modulation capability is important because heating load varies strongly during the year. However, this modulation capability is not adequate to avoid the need for these systems to cycle. For significant parts of the year, the heating load is well below 30% of the maximum heating load. It has been shown that a typical hydronic heater installed in a standard home can have a heat demand less than 25% of the nominal boiler output for 90% of the heating season.5

Cycling, generally, is undesirable in wood-pellet-fired boilers as it increases thermal stress on the system and reduces useful life. This study has also examined the effects on efficiency and emissions due to cycling.

Carlon et al. reported a comparison of the efficiency of pellet boilers in the field in Austria and from standard laboratory certification tests.6 The authors noted that in standard European certification tests of pellet boilers, efficiency is determined in steady-state operation at full load and 30% of full load. In the field, efficiency was found to be 6.9 to 24.4 percentage points lower than efficiencies certified by laboratory tests at nominal load due to cycling. None of these boilers were installed with thermal storage for the heating load. Decreasing the load was found to increase cycling and decrease efficiency, so the authors developed a suggested correlation curve for the degradation of efficiency with load in the field.

The rate of cycling under low-load conditions can be reduced by using thermal storage in the heating loop, and many manufacturers now specify that storage should or must be used with pellet-fired boilers. The benefit of thermal storage in improving the performance of pellet boilers in the field and the importance of thermal storage stratification were demonstrated by Wang et al.7,8 The group estimated from field data with homes that use thermal storage an annual fuel use reduction due to a use of thermal storage of 23.3%. This reduction in fuel use directly reduces annual emissions. In addition to the direct effects of annual fuel use, they estimate potential benefits of reducing the high-emission transient periods. These results are presented in the form of emission reduction (mg) per ignition event, but an annual impact was not estimated. This group later used these results to develop a method for optimal design of thermal storage with a pellet boiler using dynamic simulation.9

Currently, in the US, there is considerable interest in the development of new certification test methods that better reflect field operations. Historically, test methods for cordwood hydronic heaters have not considered the impact of thermal storage. Certification test methods also only consider four different load levels where a complete charge of fuel is burned at each steady load. Presently, in the United States, there is not an accepted primary test method for evaluating the thermal efficiency and emissions of an automatic-feed boiler (e.g., pellet- or chip-fueled) when integrated with external thermal storage. Part of the motivation of this work was to develop experience and data that would provide a foundation for the future development of such a test procedure.

The project team has been involved with the development of an alternative test method for cordwood hydronic heaters where thermal storage is used. In the development of this method, studies were done on the importance of transient emissions (startup and burnout) in addition to the steady state. Methods for real-time transient emission measurements were also explored. The new test method developed has been formally adopted by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for use in product certification with storage.10 This new method specifically requires measurement and reporting of the emissions for each major phase. As in prior methods, four defined loads are used. This approach is being extended to test methods that involve emulated field load profiles in place of defined fixed loads.11,12 These newer approaches are enabled, in part, by improved data acquisition and control tools and also improved tools for real-time particulate measurements.

In the current study, an examination of the performance of a wood-pellet-fired residential heating boiler under different laboratory load conditions and with different levels of thermal storage in the lab has been completed. The objectives were to improve understanding of the cycling behavior of such a boiler and to quantify the effects of thermal storage under fixed load and different exploratory load conditions.

In this study, two different types of load patterns were used for testing. The first type of load pattern was developed from EPA certification test methods 28 WHH and 28 WHH PTS.13 These methods define tests under four load categories as listed in Table 1. Categories I and IV were used in this work. Category IV is a full-load test, and the unit operates in the steady state. Category I is below the minimum modulation point, and the unit must cycle. These two modes capture the essential parts of the operation of these units.

Table 1. Burn Rate Categories Based on EPA Methods 28 WHH and 28 WHH PTS.

| Category I | Category II | Category III | Category IV |

|---|---|---|---|

| <15% | 16–24% | 25–50% | maximum burn rate |

In EPA Method 28 WHH PTS, the Category II and III tests are optional. The testing organization has the option to apply the results of the Category I test, considered to be more challenging, to the Category II and III cases for the determination of the annual averages of efficiency and emissions. For this reason, testing under these categories was not done under this project.

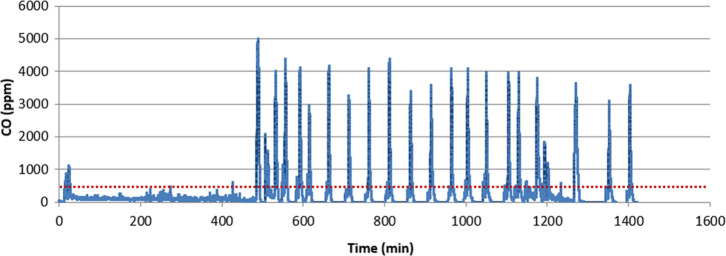

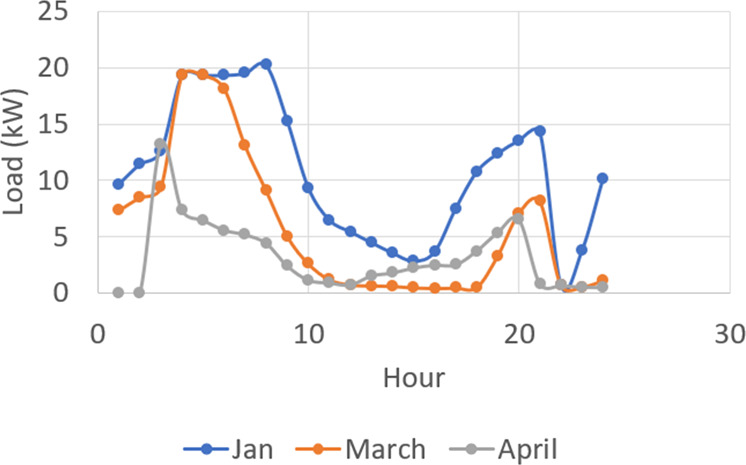

The second type of load pattern studied involved a much more varied set of patterns intended to emulate expected real field use. To develop these profiles, a building heat load analysis program (Energy-10 software14,15) was used to determine heat loss from a 232 m2 model home located in Albany, NY. This software produces the hourly heat demand for 8760 h of the year. Standard code construction was assumed as well as nighttime temperature setback to 18 °C. The home used for this example is a very typical ranch-style home common across the parts of the United States where a hydronic heater might be used. Added to the heat load profile was a domestic hot water demand profile for each day. From the energy demand profiles generated in this way, the hourly heat demand profiles seen as typical for each January, March, and April day were selected. These profiles are illustrated in Figure 1. All the profiles show a very strong increase in the heat demand in the early morning hours. This is the response of the system in recovery from nighttime setback. The peak heat load is 19.3 kW, and this is set as much by the heat delivery capacity of the thermal distribution system as by the heat load on the structure. For the January profile, the peak load is higher, approaching 20.5 kW, and is due to the combination of heat load and domestic hot water load on the selected day. All the days show a low heat demand in the afternoon as the solar gain reduces the demand on the heating system. In all cases, the heat demand becomes very low in the evening as the night setback control becomes activated.

Figure 1.

Typical field load profiles for a 232 m2 ranch home in Albany, New York.

In all three cases, the heating and domestic hot water demand never reach the boiler’s nominal rating of 25 kW. It is very common that boilers are oversized for the home. Specifically, in ANSI/ASHRAE 103-2017: Method of Testing for Annual Fuel Utilization Efficiency of Residential Central Furnaces and Boilers, an oversize factor of 0.7 is used as the national average oversize factor. For the efficiency determination under this standard, it is assumed that the boiler is sized with a maximum output capacity of 170% of the home heating load.16

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Efficiency and Emission Test Results

Table 2 provides a summary of results for efficiency and particulate matter emissions for the full set of performance tests done. The highest efficiency of 80.8% was achieved during the high-load, January profile day with 450 L of external storage. This level of efficiency was also reached during the high-load, steady-state test. During these tests, relatively low particulate emissions were also measured.

Table 2. Summary of Efficiency and Particulate Emission Results.

| test | category or profile load | thermal storage (L) | average output (kW) | efficiency (%) | PM index (g/kg fuel) | PM factor (mg/MJ output) | PM rate (g/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Category IV | none | 22.6 | 80.0 | 1.03 | 64 | 5.16 |

| 2 | Category IV | none | 21.4 | 80.7 | 0.88 | 56 | 4.42 |

| 3 | Category I | none | 2.97 | 56.5 | 1.89 | 172 | 1.97 |

| 4 | Category I | none | 3.17 | 56.2 | 1.99 | 181 | 2.10 |

| 5 | Category I | 450 | 3.27 | 59.5 | 1.04 | 69 | 1.11 |

| 6 | Category I | 450 | 2.86 | 61.1 | 1.79 | 108 | 1.50 |

| 7 | Category I | 450 | 3.55 | 68.1 | 0.87 | 65 | 1.15 |

| 8 | Category I | 450 | 3.21 | 71.3 | 0.77 | 56 | 1.16 |

| 9 | Category I | 795 | 3.24 | 74.1 | 0.83 | 60 | 1.21 |

| 10 | April | none | 2.99 | 58.7 | 1.73 | 146 | 1.68 |

| 11 | January | none | 11.1 | 77.0 | 0.96 | 64 | 2.59 |

| 12 | March | none | 5.99 | 76.4 | 1.04 | 69 | 1.56 |

| 13 | April | 450 | 3.12 | 69.7 | 0.89 | 64 | 0.77 |

| 14 | January | 450 | 10.9 | 80.8 | 0.75 | 52 | 2.03 |

| 15 | March | 450 | 5.50 | 75.4 | 0.74 | 52 | 1.01 |

| 16 | April | 795 | 3.18 | 73.6 | 1.20 | 86 | 1.15 |

The lowest efficiency of 56.2–56.5% was measured during the low-load, Category I tests without external thermal storage. During these tests, the highest particulate emissions were also measured. The average cycle period was much lower, and the rate of cycling was much higher without the use of thermal storage and is discussed below in detail.

As discussed in the Experimental Section, tests were conducted with different levels of external thermal storage and also with different settings of the temperature range over which the external thermal storage was controlled to operate over. Under a fixed low-load condition such as the Category I case, these two parameters can be evaluated in a common way using the time period of the firing cycle at fixed load. Increasing the storage volume and the controlled storage tank temperature range both increased the cycling time period.

One of the largest discrepancies in the results shown in Table 2 is from Category I tests with 450 L of storage, specifically Test 6, which is over double the lowest calculated PM emission index in Test 8. This is due to a lower measured boiler output. Tests 5, 7, and 8 measured an average of 3.21–3.55 kW, while Test 6 had an average of 2.86 kW of output. Category I testing requires the boiler to operate at or below 15% of its nominal output—for this case, 3.66 kW. The higher emissions are associated with the lower output of the boiler in Test 6 than in others and the difficulty of modulating to such a low output rate.

The coefficient of variation (COV) was calculated for the measured and calculated values in Table 2 above for any test done in multiples (i.e., Tests 1 and 2, Tests 3 and 4, and Tests 5–8). For each case, the COV for the measured average output was below 10%, falling within a very good range in terms of test variability. The calculated COV in terms of efficiency as well fell below 10% for all three cases. The COV for the PM index, PM factor, and PM rate for Tests 1 and 2 and Tests 3 and 4 was always less than 11%, and the calculated PM rate for Category I tests with 450 L of storage was calculated to be 15%, indicating good repeatability as well. However, the calculated COV for the PM index and PM factor fell above 30% indicating strong variability. Given these results, one could presume that the results from Tests 9 through 16, which were only run once each, would fall somewhere within an acceptable range.

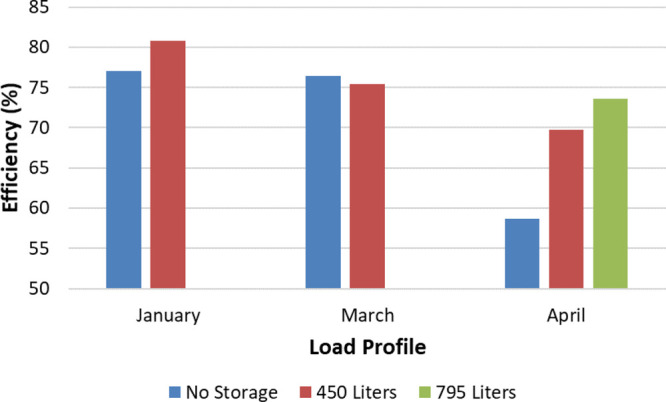

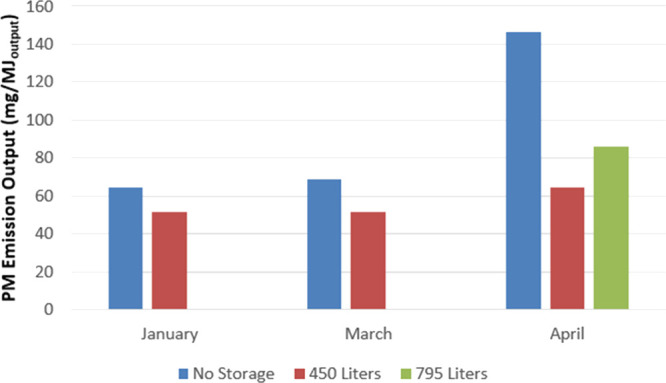

A comparison of the efficiency and particulate emissions for the January, March, and April profile runs is provided in Figures 2 and 3. The results show, for these complex load profile runs, that there was improved performance with storage generally, but this is most strongly evident in the low-load, April condition. The results for the March run are an obvious exception where the measured efficiency was slightly higher for the case. Thermal storage improves boiler efficiency by reducing cycling and energy losses during pre- and post-burner operations. Energy losses from the storage tank can reduce system efficiency. The overall impact of storage is a combination of these two impacts. During these profile runs, there is a complex combination of different types of operating periods. For the March day, the difference in the measured efficiency over the entire test with and without the storage is not considered significant and there was no significant effect of the thermal storage on efficiency. For comparison, the typical annual efficiency of an oil-fired boiler is 84%.17

Figure 2.

Profile runs, efficiency comparison.

Figure 3.

Profile runs, particulate emission factor comparison.

Table 3 provides carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4) data for some of the tests. Overall, the low-load tests (Category I) had higher gaseous emissions than the high-load tests (Category IV), run in steady-state high-load output. Including thermal storage in the Category I tests caused the CO emissions to decrease by 66% and the methane to decrease by 75%.

Table 3. Gas-Phase Emissions for Selected Tests.

| flue

gas average composition |

emission

index (g/kg fuel) |

emission

factor (mg/MJinput) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| case | CO2 (%) | CO (ppm) | methane (ppm) | CO | methane | CO | methane |

| Category IV (steady state high load) | 10.4 | 93 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 2.7 × 10–2 | 56 | 1.5 |

| Category IV (steady state high load) | 7.1 | 203 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 6.2 × 10–2 | 180 | 3.4 |

| Category I (low load) no thermal storage | 5.8 | 588 | 12.0 | 12 | 1.4 × 10–1 | 640 | 7.4 |

| Category I (low load) with 450 L of thermal storage | 10.3 | 218 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 2.9 × 10–2 | 180 | 2.1 |

| Category I (low load) with 795 L of thermal storage | 8.4 | 288 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 × 10–2 | 220 | 1.9 |

The current US EPA emission limit for residential hydronic heaters is based on the four-category test discussed in Section 1. The requirement is 43 mg/MJoutput of particulates, and this must be met in each of the four test categories.13 This regulation became effective in 2020. Prior to this date, the limit was 138 mg/MJoutput. Most of the values reported in this work are lower than the pre-2020 limits. The notable exception is the low-load tests without storage. All of the results reported in this work are higher than the 2020 limit.

In accordance with the European EN303-5 norm,18 the limit for small pellet boiler particulate emissions as of 2015 is 20 mg/MJinput. Measurement methods vary by country in the European Union, but generally, this is based on only testing at full-load, steady-state output. Further, unlike the US methods, a hot, in-stack filter method is used. With this method, measured particulate emissions can be significantly lower because condensable organics are not captured as they are in the United States, i.e., the dilution tunnel method.2

In the field study reported by Wang et al.7,8 of two residential pellet boilers with thermal storage, the average particulate emission was found to range from 9.3 to 13.9 mg/MJ using a dilution sampling approach. Ozgen et al.19 studied the emission performance of a pellet boiler in the steady state using a dilution tunnel and reported an emission factor of 85 mg/MJ.

2.2. Thermal Storage, Temperature Profiles, and Cycle Time Trends for Category I Tests

In this section, the impact of thermal storage on cycle time and temperature trends is illustrated using the results of Category I steady-load tests. For the tests with storage included in this section, the second set of control settings (74/63 °C) as discussed in Section 4.5.2 were used.

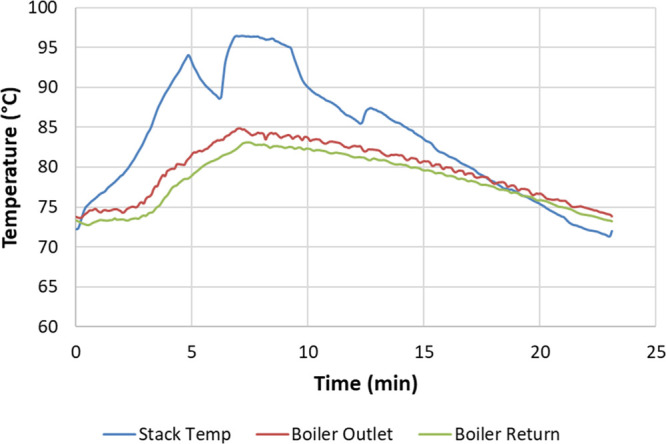

For the case of no thermal storage, the boiler cycles on and off based on its internal temperature sensor. Figure 4 shows the trend in boiler supply and return temperatures over one full cycle for this case.

Figure 4.

Temperature trends during one cycle. No thermal storage, steady load at the Category I level.

The time axis in Figure 4 is from the start of the selected cycle with the burner starting at 0 min. After approximately 5 min, the modulation control acts to reduce the firing rate leading to the reduction in stack temperature. The boiler control begins the burner shutdown process at 9.3 min. The entire cycle has a duration of 23 min, after which the burner restarts. The average temperature of the supply to the thermal distribution system (load heat exchanger in this lab configuration) is 79.5 °C.

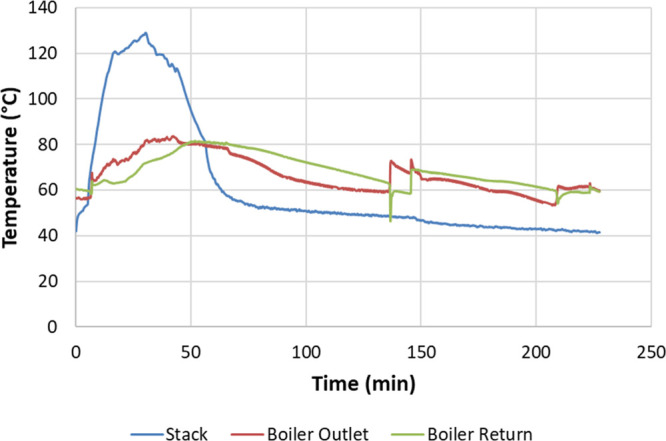

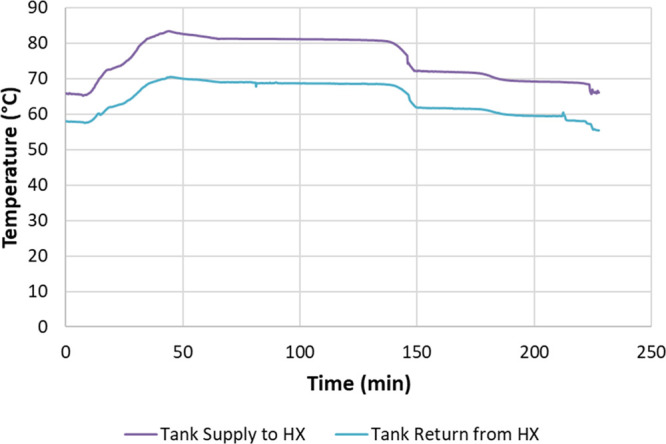

For this same load case and 450 L of thermal storage, Figure 5 shows the trends in boiler stack temperature, outlet temperature, and return water temperature. Figure 6, for this load case, also shows the temperature of the hot water from the storage tank to the load heat exchanger and the return temperature from the heat exchanger. In this case, the total cycle time is 228 min. The burner starts at 0 min and stops at 45 min. The storage tank in this case is well stratified. At 140 min, the colder water in the lower part of the tank has reached the upper part of the tank leading to a strong decrease in the temperature of the supply water to the load heat exchanger. Also, at about this time, the temperature of the water in the storage tank at the boiler control sensor location has decreased below the temperature of the boiler water and the control acts to circulate water from the boiler to the tank, transferring residual heat from the boiler into the tank. The average temperature of the supply to the thermal distribution system is 75.7 °C.

Figure 5.

Category I heat load, 450 L of thermal storage. Trends in stack temperature, boiler outlet, and boiler return temperatures.

Figure 6.

Category I heat load, 450 L of thermal storage. Trends in temperature of supply and return temperature from the tank to the load heat exchanger.

The programming and function of the modulation control system on the boiler is the same with and without storage. This system responds to boiler temperature only and not storage tank temperature. The trends in the firing rate, flue gas temperature, and boiler water temperature as the boiler approaches its temperature setpoint are different with and without storage because there is more mass involved with storage and temperatures change more slowly.

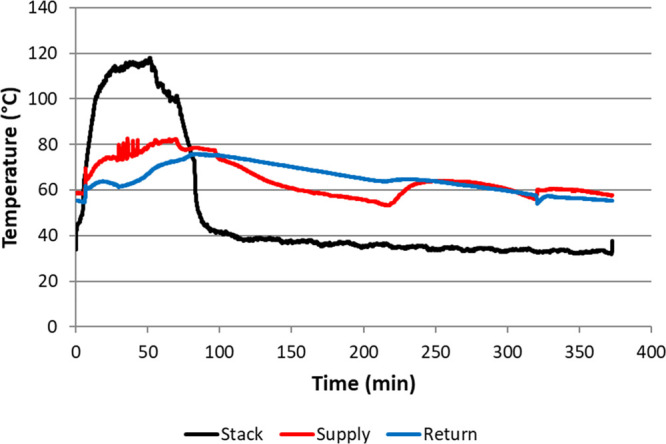

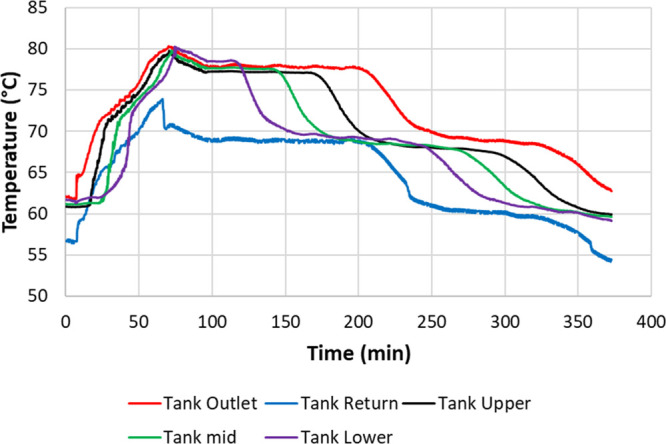

Figures 7 and 8 show the same trends for the Category I load with the largest storage volume studied, 795 L. From Figure 7, the total cycle length is 373 min and the burner ran from 0 to 69 min. For this case, the storage tank used has additional temperature measurement ports available, providing locations to measure temperatures in the tank in the upper, mid-, and lower parts. These are located 2/3, 1/2, and 1/3 of the distance from the bottom of the tank, respectively. Figure 8 includes these temperature points along with the tank supply to and return from the load heat exchanger.

Figure 7.

Category I heat load, 795 L of thermal storage. Trends in stack temperature, boiler outlet and boiler return temperatures.

Figure 8.

Category I heat load, 795 L of thermal storage. Trends in temperature of supply and return temperatures from the tank to the load heat exchanger and tank internal temperatures.

The results for this larger storage volume clearly show the tank stratification. During the period when the tank is cooling (after ∼70 min in this figure), the cooler return water from the load heat exchanger successively reaches the lower, mid-, upper, and outlet measurement points. Temperatures at these measurement points remain nearly steady until the layer of colder return water reaches them, indicating limited bulk mixing in the tank. This level of stratification is desired to enable delivery of the hottest temperature water to the heat distribution system, maintaining delivery capacity, even as the tank cools. The average temperature of the supply to the heat exchanger over the whole cycle was 73 °C. Also, for this case during the “charging” part of the cycle, when the burner is firing, the temperature rises first in the upper part of the tank as the hot water from the boiler flows from top to bottom in the tank.

From the results presented in this section, a comparison of the impact of thermal storage on the number of cycles can be made assuming a 24 h period over which there is a steady, Category I thermal load. In this case, the number of daily cycles would be 62.6, 6.3, and 3.8 with no storage, 450 L of storage, and 795 L of storage, respectively. Without storage, the daily number of cycles is 16.5 times greater than that with 795 L of storage.

2.3. Impact of Storage on Steady Low-Load Test Results

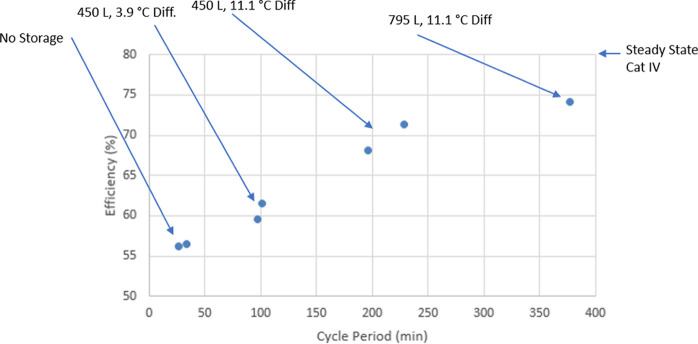

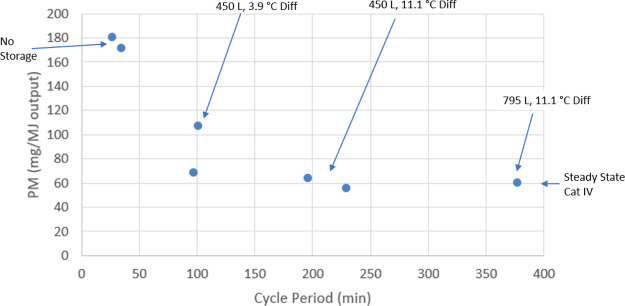

For the Category I low-load tests, Figure 9 provides a comparison of measured efficiencies. The lowest efficiency was observed when the unit operated without external thermal storage and also had the shortest cycle periods. As the storage was increased through a combination of increased storage volume and control setting temperature differential, the efficiency increased. As efficiency increased with increasing cycle period, particulate emissions decreased as shown in Figure 10. In the case of no thermal storage, an average particulate emission rate of 176 mg/MJ was measured – nearly 4 times greater than the US 2020 limit. When 450 L of storage was added, even with a differential of 3.9 °C, emissions were reduced by nearly 50%. As the system control was changed to the larger differential, the emissions decreased again by roughly a factor of 1.5. Finally, with the 795 L storage tank and the 11.1 °C differential, the emissions were the lowest and close to the US 2020 limit of 43 mg/MJ.

Figure 9.

Category I runs, illustration of the relationship between the cycle period and efficiency. Increasing storage increases the cycle period and improves efficiency. At the highest value for the cycle period, the efficiency approaches that of steady-state operation.

Figure 10.

Category I runs, illustration of the relationship between the cycle period and particulate emission factor. Increasing storage increases the cycle period and reduces particulate emissions. At the highest value for the cycle period, the particulate emission factor equals that of steady-state operation.

Results of this work have shown that thermal storage provides the most significant improvements in efficiency and emissions under low loads where the boiler cycles. As discussed in Section 1, boiler heat demand can be under 25% for 90% of the heating season. In determining annual values for efficiency and emissions, the EPA certification test methods provide weighting factors for each of the four standard test load categories. In this scheme, full-load steady-state testing is given only a weighting of 5%. The loads under the 30% minimum modulation point, Categories I and II combined, are given a total weighting of 67.5% illustrating the importance of these low-load periods in the total annual performance.

2.4. Cycling Behavior

Every time the pellet-fired boiler starts, the control takes it through a set of steps. The steps and approximate times during startup are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Phases of Startup with the Tested Pellet Boiler.

| phase | time (min) |

|---|---|

| flush | 2 |

| fill | 1 1/2 |

| ignite | 2 |

| stabilize | 5 |

| automatic |

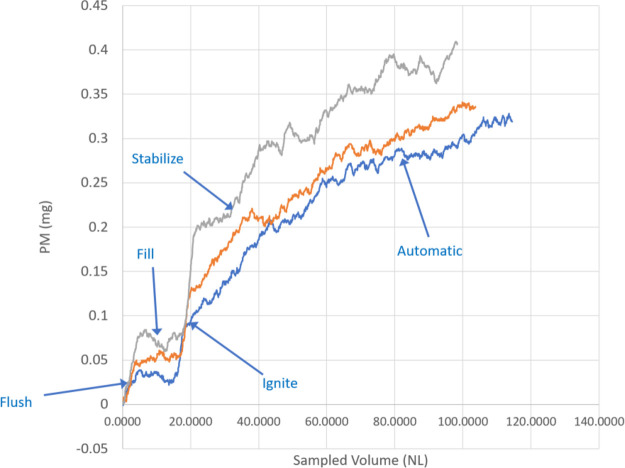

During the “Flush” phase, the fan operates to clear out any residual combustible gases and the bottom ash door opens to dump any remaining ash into the pit below. Typically, during this time period, there is a pulse of particulates emitted into the exhaust. During the “Fill” stage, pellets are delivered by auger onto the fire bed. During this period, there typically is no significant particulate emission. In the “Ignite” phase, an electrically heated stream of air at very high temperature is directed onto the fresh pellet bed leading to ignition. This process takes about 2 min as the air and bed increase in temperature to the ignition point. During most of this time, there is no clear combustion occurring. When the bed does ignite, there is typically a short period with high PM and CO emissions. Following ignition, the air feed rate is slowly ramped up as the flame spreads throughout the whole bed, the combustion chamber area heats, and flame reaches its stable full output condition. After this period, there is “Automatic” operation in which the firing rate can modulate based on the boiler temperature. This is typically the cleanest part of the operating cycle. With a steady load, the Automatic period will end when the boiler temperature rises to the operating limit. If the load on the system is at or above the maximum rated load, the burner will continue to fire.

After the boiler reaches its operating limit temperature, the burner shuts down again in phases. The first phase is “Burnout” where no additional fuel is fed and the pellets remaining in the burner chamber slowly combust. This runs for 8 to 10 min. Following this, there is about 3 min of post-ventilation in which the fan runs to clear out the combustion zone. The burner is then in a standby mode until the next firing cycle.

Figure 11 shows the results of the transient particulate measurements during three consecutive startups during a Category I test. This figure is total collected particulates vs total volume sampled using a real-time PM instrument as discussed in Section 4. The slope of the curve at any point, then, is the particulate emission concentration (mg/m3) in the dilution tunnel at that time. This figure shows a relatively consistent pattern between each startup cycle in which there is a significant emission of particulates during the fill and ignition phases, certainly higher than the steady state.

Figure 11.

Dilution tunnel real-time particulate concentration measurement results. PM is cumulative particulate matter in mg. Sampled volume is in normal liters, and the sampling rate is fixed at 4.5 L/min.

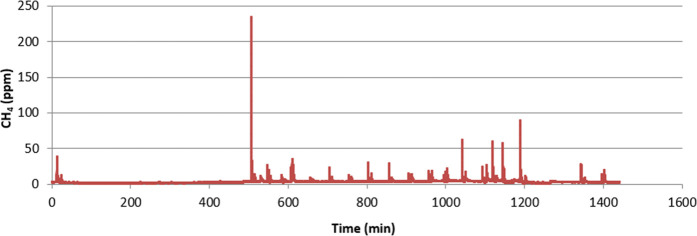

For a further example, Figure 12 shows the trend in measured stack CO during a 24 h emulated March day run without thermal storage. The dotted line in Figure 12 shows the certification limit (400 ppm air-free) for natural-gas-fired appliances, illustrating the drastic CO emissions associated with wood burning appliances and cycling. Figure 13 shows the trend in stack methane concentration for the same test. During the first 500 min of this test, the load was relatively high as the system recovered from night temperature setback, and the unit did not cycle. After this time, when the load was low, the unit cycled a great deal and every ignition event led to strong peaks in CO and methane emissions.

Figure 12.

Stack CO concentration trend. 24 h March day emulation run without thermal storage. The dotted red line in this figure illustrates the 400 ppm (air-free) limit used in certification test codes for natural-gas-fired appliances, illustrating the much higher CO levels normal with wood pellet firing under cycling conditions.

Figure 13.

Stack methane concentration trend. 24 h March day emulation run without thermal storage.

For perspective, a comparison can be made of the emission factors for the combustion of No. 2 heating oil. From Table 2, the emission factor for particulates from the pellet boiler ranged from 42 to 102 mg/MJ of heat input. Note that the output-based PM factor in this table has been converted to an input-based emission factor using efficiency. The current version of EPA AP 42 provides an input particulate emission factor for the combustion of low-sulfur No. 2 (500 ppm S) heating oil of 0.025 mg/MJ.20 From Table 3, the emission factor for CO with the pellet boiler ranges from 56 to 640 mg/MJinput. AP 42 gives an emission factor of 0.5 mg/MJ for CO with the same low-sulfur No. 2 heating oil. Again, using Table 3, the emission factor for methane with the pellet boiler ranged from 1.5 to 7.4 mg/MJinput. Data on methane emissions with No. 2 oil firing is very limited. The EPA compilation of emission factors provides methane values ranging from 0.67 mg/MJ for commercial boilers to 5.6 mg/MJ for residential furnaces. Under real-world operating conditions, Ozgen and Caserini found an 8 kW pellet stove and 25 kW pellet boiler to have methane emission factors of 9.0 and 4.0 mg/MJ, respectively, agreeing closely with our measured values.21

2.5. Storage Tank Heat Loss

In the case of the 450 and 795 L storage tanks, the rates of heat loss were found to be 0.29 and 0.15 kW, respectively. The lower rate of heat loss with the larger tank was due simply to better insulation.

A tank heat loss of 0.29 kW represents a loss of 1.2% of the full-load output of the boiler and 7.7% of the output at a steady load of 15% of the full-load output. A tank heat loss of 0.16 kW represents a loss of 0.6% of the full-load output of the boiler and 4.3% of the output at a steady load of 15% of the full-load output. Proper insulation of the storage tank and all connected piping and fittings are important for achieving high operational efficiency.

3. Conclusions

Based on all the results of the studies performed, the following conclusions are drawn: During cyclic operation, the pellet boiler studied goes through a standard series of steps including purge, cleaning, ignition, ramp-up to steady operation, steady operation, burnout, and post purge. These steps have higher particulate emissions and lower efficiency than steady-state operation.

In this work, the steady-state low-load condition was taken at 15% of the full-load output. Without external thermal storage, the boiler cycles frequently to meet this load. The total cycle period is 23 min without storage, and the processes associated with startup and shutdown are significant parts of this total period. The addition of external thermal storage greatly increases the total cycle period and reduces the startup and shutdown transients. The volume of water in the storage and the range of temperature set in the control system also determine the cycle time. With a storage volume of 450 L and a temperature differential of 11.1 °C, the total cycle period in this load condition was 228 min. With a storage volume of 795 L and a similar temperature range, the total cycle period was 373 min. Increasing the cycle period over this range increased the efficiency from 56 to 74% under this load condition and reduced particulate emissions by 66% from 176 to 60 mg/MJ.

The benefits of thermal storage are greatest at low loads, and it has been shown that units of this type operate for a very large fraction of the year in such low-load conditions.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Boiler Description

The boiler used during the study was a residential wood-pellet boiler with a nominal rated output capacity of 25 kW. This boiler has a 37.9 L internal water capacity, and the manufacturer recommends use with a 450 L or larger external thermal storage (“buffer”) tank. The boiler is operated with a microprocessor control and is equipped with a lambda sensor in order to measure residual flue gas oxygen and adjust fuel feeding rates accordingly. Technical specifications include a secondary fan, exhaust fan, automatic ignition, automatic ash cleaning, a stainless-steel firebox, and a drop grate system.

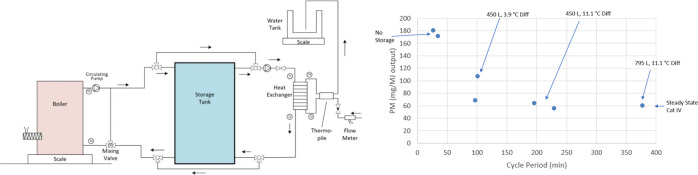

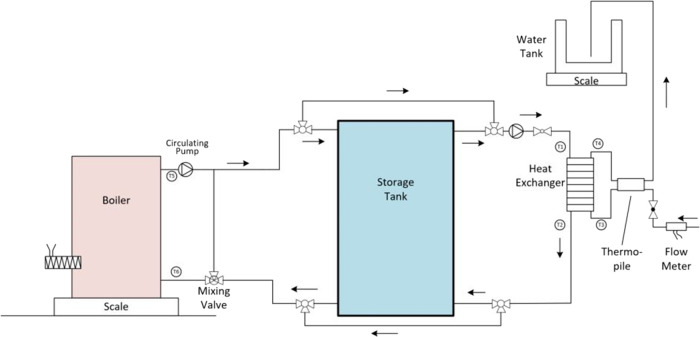

4.2. Test Lab Facilities

Figure 14 provides a sketch of the boiler hydronic setup in the lab. The boiler is installed on a weigh scale and has a small capacity pellet feed hopper attached so that the fuel burn rate can be directly determined from the mass change. This hopper may be refilled during test runs, depending on the load and cycling pattern. The weigh scale upon which the boiler and hopper sit has a rated capacity of 2722 kg and a resolution of 0.09 kg. As per the manufacturer’s installation instructions, the boiler has a piping loop with a mixing valve to ensure that cold water, below 54 °C, does not return to the boiler. The system, as shown, includes a storage tank, and the piping is arranged so that the flow from the boiler can either go into the storage tank or bypass the storage tank flowing directly to the load heat exchanger. This enables testing both with and without thermal storage. The load heat discharge section consists of two plate-type heat exchangers in parallel inside a foam insulated box. On the other, or open, side of the heat exchanger, cold “city” water flows at a controlled rate to impose the target load. The flow rate is controlled and measured using a Belimo model ePIV control module. From the heat exchanger, the cooling water is directed to a weigh scale located on the floor above for a direct mass measurement of the cooling water flow rate. The 189 L tank on the weigh scale must be periodically emptied. This is automated, and the flow meter output is used during these brief times to determine the flow rate for energy output purposes.

Figure 14.

In-lab test arrangement.

The flow rate of supply to the load heat exchanger was adjusted to provide a temperature drop across the heat exchanger of 6.6 °C (supply-return) to approximate the performance expected in the field. The concern here was to avoid high flow rates that could unrealistically de-stratify the storage tank. Under variable load conditions, this flow rate was set at a high-output condition at the highest temperature observed during cyclic operation. This would give lower temperature changes in lower-output conditions.

Two different insulated storage tanks were used during this project, one with 450 L of storage and the second with 795 L of storage. The smaller of these two tanks represents the manufacturer’s specified storage volume for this unit. The larger tank was tested to evaluate the impact of increasing the storage volume.

4.3. Measurements

The particulate emissions were collected from the dilution tunnel and conducted in compliance with ASTM E2515-10.22 Details of particulate matter (PM) and gaseous sampling from the dilution tunnel are similar and described in the measurement techniques section by Trojanowski et al.23

Some of the sampling was integrated over an entire test period. In other tests, sampling was done during discrete phases of operation, for example, startup, steady firing, and burnout. When phase sampling was done, train front filters only were changed between phases, and this procedure was accomplished typically in less than 1 min. Back filters were not changed because the mass collected was negligible and changing these filters would have slowed the filter change process. Any mass collected on the back filter was apportioned to the mass collected on the front filters.

For some of the testing done with this boiler, particulate emissions in the dilution tunnel were measured using a real-time particulate concentration monitor. The unit used was the Wöhler SM500, which is currently used for field in-stack particulate concentration measurements in Germany. This is a tapered element oscillating microbalance (TEOM)-type measurement device and provided, in this project, the opportunity to study (at least qualitatively) particulate emissions during start and stop operation of the pellet boiler.

For cooling water flow control and logging of flue gas composition, cooling water flow, boiler scale mass, dilution tunnel velocity, and cooling water inlet and outlet temperatures, a laboratory data acquisition (DAQ) system was used. The signals from all analyzers were logged at 5 s intervals. Each gas analyzer had a resolution of 0.1% of full scale. The programming allowed for a target heat output rate and the cooling water flow was continuously adjusted to achieve the target output. The target load could be constant over the test or a profile could be used with variable target load. To create the target load profile, a separate text file was created and loaded into the DAQ program. In testing under this project, up to 24 load “steps” were used in some tests, although programs with a much higher number of load steps could be used.

Table 5 provides a summary of all the instruments with their make, model, measurement principle, measurement resolution, and accuracy.

Table 5. Summary of Measurement Methods.

| |

measurement |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| analysis | measurement principle | instrument manufacturer | model | resolution | accuracy | |

| glue gas concentrations | CO, CO2, methane | nondispersive infrared (NDIR) | California Analytical Instruments (CAI) | ZRE analyzer | 0.1% | 2%b |

| O2 | paramagnetic | Beckman/Rosemount | 755 | 2%b | ||

| temperature | Peltier effect | Omega Engineering | Type K thermocouple | 0.1 °C | 2.2 °C/0.75% | |

| particulate matter | cumulativea | gravimetric | Mettler Toledo | MS205DU | 0.01 mg | ±0.02 mg |

| real-time | tapered element oscillating microbalance | Wöhler | SM 500 Suspended Particle Analyzer | 0.1 mg | filter load ±0.3 mg | |

| sample rate ±5% | ||||||

| weight of fuel consumed | gravimetric | Data Weighing Systems | CAPS4U-5000NN-LU (floor scale) | 0.1 kg | ±0.05 kg | |

| volumetric gas flowa | dry gas meter | Apex Instruments | XC-5000 AutoKinetic Sampling Console | 1 cc | 0.50 cc | |

| flow rate of water from the heat exchanger to determine boiler output | control valve | Belimo Aircontrols | Electronic Pressure Independent control Calves (ePIV) | flow control tolerance ±5% | 0% leakage | |

| flow measurement tolerance ±2% | ||||||

| gravimetric | Sartorius | CISL1U | 0.005 kg | ±0.2 kg | ||

| storage tank heat loss | infrared imaging | FLIR Tools | C3 | 0.3 MP | ±2% or ±2 °C whichever is greater | |

In accordance with ASTM E2515-10.

All gas analyzers were calibrated with certified grade gases from Matheson Tri-Gas Co. This grade provides an accuracy of 2%.

The efficiency

of the boiler is measure of the output/input  The output of the boiler is determined

by the mass flow rate of the water from the heat exchanger (city water

side) and the rise in temperature, as shown in the equation below.

The output of the boiler is determined

by the mass flow rate of the water from the heat exchanger (city water

side) and the rise in temperature, as shown in the equation below.

The measure of input to the boiler is determined by the amount of fuel consumed for the given time multiplied by the higher heating value (HHV) of the fuel and the moisture content (MC) of the fuel, as shown in the equation below.

For the efficiency determination, the heat output is measured after the thermal storage tank so that heat losses from the tank are accounted for and these heat losses will decrease the efficiency.

4.4. Test Fuel

The fuel used for all tests was wood pellets with an 80% hardwood and 20% softwood composition. Table 6 provides a summary of fuel properties. Additional test fuel properties can be found in a report by Butcher.24

Table 6. Properties of Test Fuel.

| parameter | units | value |

|---|---|---|

| moisture | wt % | 3.77 |

| ash | wt % | 0.67 |

| higher heating value | kJ/kg | 19215 |

| maximum length (single pellet) | mm | 71 |

| diameter, range | mm | 6.4 to 6.6 |

| diameter, average | mm | 6.5 |

4.5. Test Load Conditions

4.5.1. Category IV

The purpose of a Category IV test is to run the boiler at 100% output for a maximum burn rate in order to verify the manufacturer’s rated output as well as determine the unit’s efficiency and PM emissions under this condition. For a Category IV test, external storage is not necessary since the boiler is operated at full load. In the case of a Category IV test, the boiler operates between 90 and 100% of full output so no cycling will occur. Category IV tests were started after the boiler was in steady-state conditions and completed after running for a minimum of 4 h.

4.5.2. Category I

The purpose of a Category I test is to run the boiler at a burn rate to achieve 15% or lower of the manufacturer’s rated output. This test is done to measure the emissions and efficiency at the low-load levels, which is when cycling is most likely to occur. Category I testing was conducted with and without storage. Prior to starting the Category I test, the system cycled at least twice at this load. Category I tests were terminated after at least two complete tank cool down/heat up cycles were completed and a minimum of 4 h had elapsed. Without storage, in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidance, the boiler control is set so that the burner fires until the boiler temperature reaches 85 °C and then starts again when boiler temperature falls to 60 °C. When storage is implemented, the boiler on/off operation is controlled by the tank temperatures, and two distinct settings for the operating temperature range with thermal storage were explored in this study. In the first, the control was set so that the burner fires when the top tank temperature falls to approximately 68 °C and then stops when the tank bottom sensor reaches approximately 72 °C. The actual differential as programmed was 3.9 °C. This approach to control settings offers the advantage of ensuring that the water provided to the heat distribution system over normal cycling is likely hot enough to deliver the full system heating capacity to the building at all times. In the second set of control settings, the burner fires on cooling when the top tank temperature reaches approximately 63 °C and then stops when the bottom temperature sensor rises to approximately 74 °C. The actual differential as programmed was 11.1 °C. Relative to the first approach above, these control settings lead to longer burner on- and off-times during cyclic operation.

The specific temperatures for both of these control settings were set in consultation with the manufacturer. These are settings which the manufacturer would likely use in actual field installations. The two different approaches were included in this study to evaluate the importance of the decision about these settings on performance.

Another factor that can affect the cycling pattern is the temperature change of the water from either the boiler or the tank across the heat exchanger. Too high a flow can de-stratify the tank, reducing the effective thermal capacity. Again, based on discussions with the manufacturer, a decision was made to target a temperature change of 6.6 °C across this heat exchanger in all tests. This was adjusted using a simple throttling valve in the flow to the heat exchanger (Figure 14). In some tests, this was difficult to achieve because of the strong change in either boiler or storage tank temperature over a profile or cycle. In this case, 6.6 °C was set with the highest temperature during the typical cycle. At lower temperatures, the temperature change across the heat exchanger would be somewhat lower. Attempting to continuously change the flow to the heat exchanger to adjust this parameter was found to lead to an unstable response of the control loop, which functioned to achieve the target output load.

A total of seven Category I tests were run as shown in Table 7. Two tests were run with no external thermal storage, four had 450 L of storage, and one had 795 L of storage to evaluate the impact that storage had on cycle time, efficiency, and emissions.

Table 7. Category I Runs - Cycle Time Period.

| test | storage (L) | storage tank differential (°C) | total system thermal storage capacity (kWh) | period (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | none | N/A | 1.73 | 34 |

| 4 | none | N/A | 1.73 | 26 |

| 5 | 450 | 3.9 | 2.47 | 97 |

| 6 | 450 | 3.9 | 2.47 | 101 |

| 7 | 450 | 11.1 | 6.78 | 196 |

| 8 | 450 | 11.1 | 6.78 | 229 |

| 9 | 795 | 11.1 | 11.12 | 337 |

Table 7 also includes the total system storage capacity in kWh. This is based on the boiler and storage tank mass of water and steel, the specific heat of each, and the normal range of temperatures that the system operates over. This value represents the total “amount of storage” for each case. As shown in Table 7, as the amount of storage increases, the cycle time period also increases.

4.5.3. Emulated Loads

In the lab, the January, March, and April emulated building loads were imposed automatically on the boiler/storage tank system using the DAQ system described in Section 4.3. This process of testing under each of these loads required a full 24 h of testing.

4.6. Storage Tank Heat Loss

Heat loss from a storage tank to the surroundings can impact the efficiency of a heating system. The configuration of the heat output measurement used here includes the tank jacket loss in the efficiency determination. However, to evaluate the importance of tank jacket loss in the overall efficiency, several methods were explored to determine the rate of heat loss from the storage tanks used. This included calculation based on internal temperature, construction, and estimated heat transfer from the surface to the surroundings by convection and radiation; measurement of the surface temperature by infrared imaging and calculation of the heat loss to the surroundings; and measurement of the decay of internal tank temperature over longer time periods.24

While several methods for determining storage tank heat loss were evaluated, use of the decay of the internal tank temperature was seen as the best approach. Calculation of the rate of heat loss from the storage tank based on internal or surface temperatures is useful in providing estimates but is subject to approximations needed for tank surface convection coefficients and emissivity. Further, penetrations in the tank, supports, fittings, valves, and other features, which may not be well insulated, contribute to heat loss and are not easily included in a tank heat loss calculation. The rate of decay of internal tank temperature is seen as a more reliable method; however, the tank temperature can be stratified, making determination of average internal temperature difficult. Continuous circulation of the water in the tank through an external piping loop during a tank idle cool down period was explored with temperature measurements made in the loop. This approach was also found to be challenging as heat losses from the pipe loop and its fittings to the room as well as heat input to the loop from the motor of the circulating pump must be considered. The approach finally chosen involved the decay of the tank temperature over several days under idle conditions without external circulation. At the start and end of the test period, the water in the tank was circulated in the external loop until a steady average temperature was found.

The tank heat loss rate is calculated as

where CSteel is the specific heat of the tank steel, CWater is the specific heat of the water in the tank, averaged over the range of test temperatures, QTankJacket is the tank rate of heat loss, ttest is the duration of the storage tank loss rate test, TFavg is the average temperature of the tank water at the end of the tank loss rate test, TIavg is the average temperature of the tank water at the start of the tank loss rate test, WTank is the mass of the dry tank, and WWaterStorage is the mass of the water in the tank.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from New York State Energy Research Development Authority (NYSERDA) is gratefully acknowledged under Agreement number 63016. The funding has provided the necessary research data to investigate the emissions and efficiency performance of a pellet-fired boiler.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- EIA Increase in wood as main source of household heating most notable in the Northeast; Energy Information Administration [ONLINE] https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=15431, Accessed March 5, 2020.

- Weiss L.; et al. New York State Wood Heat Report: An Energy, Environmental, and Market Assessment; Report 15-26, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, 2016.

- Nussbaumer T.Biomass Combustion in Europe - Overview on Technologies and Regulations; Report 08-03, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority: 2008.

- McDonald R.Evaluation of Gas, Oil and Wood Pellet-Fueled Residential Heating System Emissions Characteristics; BNL-90286-2009-IR, Brookhaven National Laboratory: 2009.

- Butcher T.; Russell N.. Review of EPA Method 28 Outdoor Wood Hydronic Heater Test Results; Report 11–17, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carlon E.; Schwarz M.; Golizca L.; Verma V. K.; Prada A.; Baratieri M.; Haslinger W.; Schmidl C. Efficiency and operational behaviour of small-scale pellet boilers installed in residential buildings. Appl. Energy 2015, 155, 854–865. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Masiol M.; Thimmaiah D.; Zhang Y.; Hopke P. K. Performance evaluation of two 25 kW residential wood pellet boiler heating systems. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 12174–12182. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b01868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Nakao S.; Thimmaiah D.; Hopke P. K. Emissions from in-use residential wood pellet boilers and potential emissions savings using thermal storage. Sci.Total Environ. 2019, 676, 564–576. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Satyro M. A.; Taylor R.; Hopke P. K. Thermal energy storage tank sizing for biomass boiler heating systems using process dynamic simulation. Energy Build. 2018, 175, 199–207. 10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA Method 28 WHH PTS - A Test Method for Certification of Cord Wood - fired Hydronic Heating Appliances with Partial Thermal Storage; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: 2019.

- Trojanowski R.; Butcher T. A.; Wei G.; Celebi Y.. Performance of a Biomass Boiler in a Load Profile; Test, BNL-211372-2019-INRE, Brookhaven National Laboratory: 2019.

- NESCAUM Test Methods, Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management; [ONLINE] https://www.nescaum.org/topics/test-methods/test-methods, Accessed March 5, 2020.

- Standards of Performance for New Residential Wood Heaters, New Residential Hydronic Heaters and Forced-Air Furnaces. Fed. Regist. 2015, 50, 13672–13753. [Google Scholar]

- Balcomb J. D.1997Energy-10: A design tool for buildings in Proc. Building Simulation ’97; International Building Performance Simulation Association: Prague. [Google Scholar]

- Walker A.; Balcomb D.; Kiss G.; Weaver N.; Becker M. H. Analyzing two federal buildings – integrated photovoltaics projects using Energy-10 simulation. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2003, 125, 28–33. 10.1115/1.1531643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelechava B.ANSI/ASHRAE 103-2017: method for testing for annual fuel utilization efficiency of residential central furnaces and boilers, American National Standards Institute; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Navigant Consulting Technology Forecast Updates- Residential and Commercial Building Technologies - Reference Case;. Energy Information AdministratiDDon: 2018.

- Norm EN 303–5 Heating boilers-Part 5: Heating boilers for solid fuels, manually and automatically stoked, nominal heat output of up to 500 kW. Terminology, requirements, testing and marking; 2012.

- Ozgen S.; Caserini S.; Galante S.; Giuliano M.; Angelino E.; Marongiu A.; Hugony F.; Migliavacca G.; Morreale C. Emission factors from small scale appliances burning wood and pellets. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 94, 144–153. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA AP 42; Fifth Edition, Volume 1, Chapter 1: External Combustion Sources. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgen S.; Caserini S. Methane emission from small residential wood combustion appliances: Experimental emission factors and warming potential. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 189, 164–173. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM Standard Test Method for Determination of Particulate Matter Emissions Collected in a Dilution Tunnel, E2515; ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski R.; Butcher T.; Wei G.; Celebi Y. Repeatability in particulate and gaseous emissions from pellet stoves for space heating. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 3543–3550. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b03977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher T.Effect of Thermal Storage on the Performance of a Wood Pellet-Fired Residential Boiler, BNL-200061-2018-INRE ,Brookhaven National Laboratory; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]