Abstract

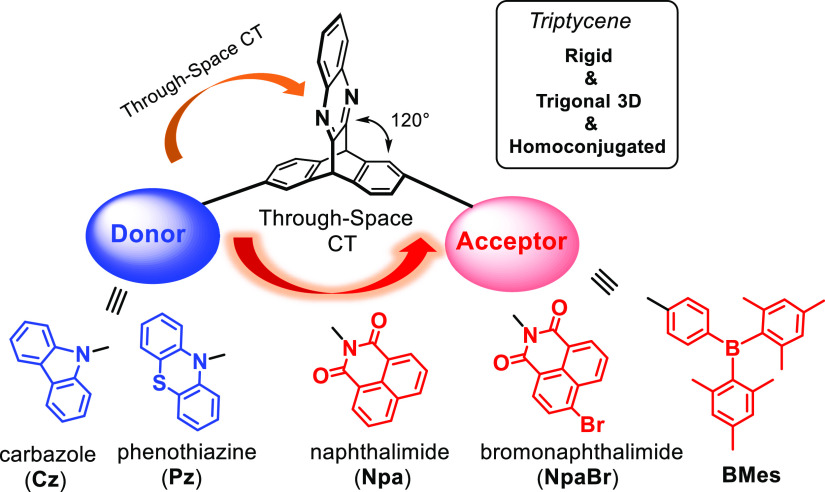

We have developed a new family of luminescent materials featuring through-space charge transfer from electron donors to acceptors that are electronically separated by triptycene. Most of these molecules are highly fluorescent, and modulation of their emissions was achieved by tuning the electron-accepting strength in a range from the weak triptycene acceptor over triarylborane (BMes) to strongly accepting naphthalimide (Npa) moieties. Pz–Pz shows an aggregation-induced emission in aggregates and in the solid state coupled with a highly red-shifted broad emission (ca. 160 nm) of the excimer, indicating that phenothiazine (Pz) also plays a vital role in the emission responses as an electron donor. This work may help develop new approaches to photophysical mechanism based on the rigid, homoconjugated, and structurally unusual 3D triptycene scaffold.

Introduction

Organic luminescent materials have received tremendous interest due to significant advances motivated by various applications in broad areas of smart sensing, security, light emitting, bioimaging and organic electronics, and so forth.1 Fully π-conjugated systems are well-known for robust functionalization with electron donors (D) and acceptors (A) that enables facile emission modulation by fine tuning their strength of electronic coupling.2 Other than this conventional molecular design, a new type of electronic interaction of through-space conjugation has recently been established for the next generation of optoelectronic materials and devices with considerably more flexible π-electron delocalization via spatial overlap of π orbitals.3 In the past few years, triptycene as a unique member of iptycenes has attracted attention in supramolecular chemistry and molecular machines due to its trigonal 3D skeleton.4 On the other hand, the unusual electronic properties of triptycene that feature a nonconjugated but structurally rigid nature of the three benzene rings fused to a central bicycle lead to the homoconjugation effect.5 Such homoconjugated electronic characteristics were previously supported by interchromophoric charge-transfer transition and other studies on triptycene derivatives.6 Given the spatially disposed homoconjugation, substantial efforts have been devoted to investigations of triptycene-based luminescent materials for thermally activated delayed fluorescence7 with fully separated highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMOs) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMOs) as well as for circularly polarized luminescence emitters and chiroptical materials.8

However, many of the traditional luminescent materials may suffer from severe emission quenching and low quantum yields in aggregates, which is unexpected and disadvantageous to light-emitting applications strongly based on the photophysical performance in solid states.9 In 2001, Tang and co-workers first proposed a conceptually new mechanism of aggregation-induced emission (AIE) opposite to commonly observed intense luminescence in well-dispersed solutions.10 Research associated with the AIE phenomenon has witnessed a rapid growth over two decades, and the community found their significant impacts on many other fields such as OLEDs, bioimaging, chiral luminescence, and drug-resistant studies.11−14 In an attempt to persistently seek new luminescent materials with tunable emissions,15 we, herein, present a large family of through-space charge-transfer systems based on the spatially distinct and electronically homoconjugated spacer of triptycene that is functionalized with shifts of electron donating and accepting strength and AIE activity (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Design of Triptycene-Based Luminescent Materials with Electron Donors and Acceptors.

Experimental Section

Materials

n-Butyllithium, phosphinic acid, potassium carbonate, pyridine, o-phenylendiamine, o-dichlorobenzene, cuprous iodide, trifluoroacetic anhydride, 18-crown-6, carbazole, phenothiazine, diisopropylethylamine, sodium t-butoxide, and tribenzylidene acetone dipalladium (II) were purchased from Energy Chemical. Tetrahydrofuran, dichloromethane, petroleum ether, methanol, and ethyl acetate were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Chemicals were used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Anhydrous solvents were distilled from commercial sources with sodium/benzopheneone or calcium hydride.

General Methods and Instrumentation

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Bruker spectrometer. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on the 101 or 176 MHz Bruker spectrometers. 11B NMR spectra were recorded on a 128 MHz Bruker spectrometer. 11B NMR spectra were acquired with boron-free quartz NMR tubes, and the spectra were referenced externally to BF3·Et2O (δ = 0). High-resolution mass spectral data were obtained via ESI on an Agilent (Q-TOF 6520) analyzer. UV–visible absorption spectra were recorded on a Cary 300 UV–vis spectrophotometer. Luminescent spectra were recorded on an Edinburgh Instrument FLS980 or Lengguang Tech F97PrO spectrophotometer. Fluorescent quantum efficiencies were determined using a Hamamatsu C11347-11 Quantaurus-QY spectrometer. X-ray single crystals were obtained on a Bruker D8 X-ray single crystal Venture diffractometer. SAINT5.0 and SADABS programs are used for the reduction and absorption correction of crystal data. The resolution and refinement of the crystal structure are obtained on SHELXTL-97 software. Using the direct or Patterson methods, all nonhydrogen source coordinates are obtained by using the differential Fourier method and the least square method. Then, the geometric method and the difference value are used. The hydrogen atom coordinates were obtained by the Fourier method, and the crystal structure was obtained. The CCDC numbers of 2011196 (Cz–Cz) and 2011197 (Pz–Pz) are deposited. DFT calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 program. Geometry optimizations and vertical excitations were calculated by means of the hybrid density functional B3LYP and CAM-B3LYP with the basis set of 6-31G*. The input files and orbital representations were generated with GaussView 5.0 (scaling radii of 75%, isovalue = 0.02). Excitation data were calculated using time-dependent density-functional theory (TD-DFT) (B3LYP/6-311G**). The true minimum of resulting structures was confirmed to be stationary points through vibrational frequency analysis with absorbance of imaginary frequencies.

Synthesis of Pz–Pz

6 (46.4 mg, 0.1 mmol), phenothiazine (43.8 mg, 2.2 equiv), t-BuONa (29 mg, 3 equiv), tris(dibenzylidineacetone)-dipalladium(0) (4.6 mg, 5%), and tri-t-butylphosphonium tetrafluoroborate (3 mg, 10%) were dissolved in dry toluene (6 mL). The mixture was degassed, heated to 107 °C, and refluxed for 20 h under N2. After the reaction was complete, the reaction was cooled to r.t, filtrated, concentrated, and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 10:1, v/v first; then dichloromethane) to give Pz–Pz as a brown solid (22 mg, 29%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.98 (dd, J = 6.2, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.8 Hz, 4H), 7.58 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.12–7.02 (m, 4H), 6.85 (dt, J = 5.8, 2.4 Hz, 8H), 6.37–6.24 (m, 4H), 5.72 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.8, 144.5, 143.8, 140.6, 140.4, 139.4, 129.6, 128.7, 127.7, 127.1, 127.0, 126.9, 125.7, 123.1, 122.4, 117.6, 55.0. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C46H28N4S2 [M + H]+, 701.1828; found, 701.1821.

Synthesis of Cz–Cz

6 (113 mg, 0.24 mmol), carbazole (90 mg, 2.2 equiv), K2CO3 (67 mg, 2 equiv), cuprous iodide (2.3 mg, 5%), and 18-crown-6 (6.5 mg, 10%) were dissolved in dry o-dichlorobenzene (5 mL). The mixture was degassed and was then heated to 180 °C and refluxed overnight under N2. After the reaction was complete, the reaction was cooled to r.t, concentrated, and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 15:1, v/v) to give Cz–Cz as a yellowish solid (14 mg, 9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.13 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 8.03 (dd, J = 6.2, 3.2 Hz, 2H), 7.85–7.77 (m, 4H), 7.73 (dd, J = 6.2, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 7.49–7.32 (m, 10H), 7.29 (dd, J = 7.8, 4.0 Hz, 4H), 5.84 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.6, 143.8, 140.8, 140.8, 139.5, 136.5, 129.7, 128.7, 126.5, 126.0, 125.6, 123.9, 123.4, 120.4, 120.2, 109.8, 55.1. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C46H28N4 [M + H]+, 637.2387; found, 637.2372.

Synthesis of Cz–BMes

Cz–Br (55 mg, 0.1 mmol), tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)-palladium(0) (18.5 mg, 5%), and 8 (45 mg, 1.2 equiv) were dissolved in toluene (6 mL). The mixture was degassed, and then, a solution of K2CO3 (83 mg, 6 equiv) dissolved in water (3 mL) was added dropwise under N2. The mixture was heated to 110 °C and refluxed overnight under N2. After the reaction was complete, the reaction was cooled to r.t, filtrated, concentrated, and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 15:1, v/v) to give Cz–BMes as a pale solid (23 mg, 29%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.11 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.99 (dq, J = 11.0, 3.7 Hz, 2H), 7.90 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.72–7.64 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.52 (m, 4H), 7.47 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.23 (m, 7H), 7.24 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (s, 4H), 5.84 (s, 1H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 2.02 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 141.1, 140.8, 138.7, 137.0, 129.5, 128.7, 128.2, 126.7, 125.9, 125.5, 123.8, 123.4, 120.3, 120.1, 109.8, 23.5, 21.2. 11B NMR (225 MHz, CDCl3): δ 28. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C58H46BN3 [M + H]+, 796.3858; found, 796.3847.

Synthesis of Pz–BMes

A similar procedure for Cz–BMes was performed to give Pz–BMes as a yellowish solid (19 mg, 28%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.97 (td, J = 7.2, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.59 (m, 4H), 7.59–7.51 (m, 5H), 7.46 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 7.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 4.2, 2.6 Hz, 2H), 6.90–6.70 (m, H), 6.23–6.11 (m, 2H), 5.75 (d, J = 35.0 Hz, 2H), 2.31 (s, 6H), 2.01 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 139.8, 137.7, 136.0, 129.2, 128.5, 127.6, 127.2, 125.8, 125.6, 124.9, 121.7, 115.8, 76.2, 28.7, 22.4, 21.7, 20.2, 13.1. 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C58H46BN3S [M + H]+, 828.3578; found, 828.3580.

Synthesis of Cz–Npa

Cz–NH2 (91 mg, 0.187 mmol) and 1,8-naphthalic anhydride (37 mg, 0.187 mmol, 1 equiv) were dissolved in acetic acid (5 mL) and refluxed for 5 h. The reaction was cooled to r.t., and 10 mL of water was added. The precipitates were recovered by filtration, and the crude product was dried under vacuo and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (dichloromethane, then methanol) to obtain Cz–Npa as a pale solid (66 mg, 53%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.62 (dd, J = 7.2, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 8.30 (dd, J = 8.2, 0.8 Hz, 2H), 8.10 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 8.02–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.82 (dd, J = 8.2, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.79–7.68 (m, 5H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.22 (m, 8H), 5.71 (d, J = 21.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.2, 156.8, 143.5, 143.0, 140.7, 140.2, 139.7, 139.2, 137.9, 131.1, 130.0, 129.7, 129.0, 128.9, 128.8, 127.1, 126.2, 124.0, 122.0, 121.4, 121.1, 120.9, 120.2, 116.1, 110.3, 51.0. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd For C46H27N4O2 [M + H]+, 667.2129; found, 667.2131.

Synthesis of Pz–Npa

A similar procedure for Cz–Npa was performed to give Pz–Npa as a yellowish solid (39 mg, 29%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.56 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 8.27–8.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (m, 2H), 7.79–7.72 (m, 3H), 7.68–7.59 (m, 4H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.22 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 7.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.98–6.89 (m, 2H), 6.75–6.69 (m, 3H), 6.11–6.07 (m, 1H), 5.65–5.51 (d, J = 19.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 159.3, 156.7, 144.4, 143.7, 143.0, 140.2, 139.5, 137.8, 137.5, 136.9, 133.2, 130.3, 128.9, 128.4, 127.4, 126.1, 125.8, 124.0, 122.1, 122.0, 117.8, 52.9. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C46H26N4O2S [M + H]+, 699.1849; found, 699.1842.

Synthesis of Cz–NpaBr

A similar procedure for Cz–Npa was performed to give Cz–NpaBr as a yellowish solid (50 mg, 35%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.96 (d, J = 8.0, 2H), 8.72 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 8.45–8.38 (m, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.98 (ddd, J = 10.2, 5.0, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 7.79–7.65 (m, 5H), 7.45 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.22 (m, 8H), 5.75–5.64 (d, J = 20.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.7, 153.3, 144.3, 143.7, 140.8, 140.4, 139.5, 139.4, 138.9, 136.5, 128.3, 127.7, 126.7, 126.6, 126.4, 125.6, 125.4, 125.2, 124.6, 123.8, 123.4, 120.6, 120.3, 120.1, 119.0, 118.9, 121.3, 109.9, 54.9. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C46H25BrN4O2 [M + H]+, 745.1234; found, 745.1228.

Synthesis of Pz–NpaBr

A similar procedure for Cz–Npa was performed to give Pz–NpaBr as a yellowish solid (55 mg, 37%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.88 (m, 2H), 8.43 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (m, 3H), 7.84–7.76 (m, 1H), 7.72–7.61 (m, 3H), 7.54–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.22–7.10 (m, 1H), 7.03 (dd, J = 7.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.90–6.83 (m, 2H), 6.73–6.64 (m, 4H), 6.11–6.07 (m, 2H), 5.55 (d, J = 21.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 160.4, 157.6, 145.4, 143.8, 143.1, 140.3, 139.0, 137.0, 136.9, 136.8, 135.4, 133.4, 131.7, 131.6, 130.8, 129.9, 128.9, 128.8, 128.2, 127.3, 126.1, 125.8, 124.4, 122.6, 121.9, 120.9, 117.9, 57.4. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd for C46H25BrN4O2S [M + H]+, 777.0954; found, 777.0949.

Results and Discussion

The synthetic details are described above and in the Supporting Information. A key step to achieve triptycene derivatives is the scalable synthesis of bifunctional compound 6, which was obtained via a modified procedure in the previous report.16 As shown in Scheme 2, the coupling reactions of 6 with electron donors were performed by Cu(I)-catalyzed Ullmann reaction for carbazole (Cz, 2.0 equiv) and Buchwald–Hartwig reaction for phenothiazine (Pz, 2.2 equiv), leading to symmetrical Cz–Cz and Pz–Pz, respectively. Under similar conditions, we first prepared the intermediates monofunctionalized with Cz and Pz, and they were then reacted with triarylborane (BMes) as a moderate acceptor in Suzuki cross-coupling to give D–A type molecules Cz–BMes and Pz–BMes. They were also coupled with strongly electron-accepting groups of naphthalimide (Npa) and bromonaphthalimide (NpaBr) via the condensation reaction of primary amines and anhydrides, giving rise to highly efficient D–A charge-transfer systems of Cz–Npa, Cz–NpaBr, Pz–Npa, and Pz–NpaBr. These products have been fully characterized by 1H, 13C, and 11B NMR and high-resolution mass spectroscopic analysis.

Scheme 2. Synthesis and Structures of Triptycen-Based Luminescent Molecules.

Reagents and conditions: (i) with modified procedures in ref (16): (a) vinylene carbonate, hydroquinone (5%), 190 °C, 3 d; (b) KOH, H2O, reflux; (c) trifluoroacetic anhydride, N-ethyldiisopropylamine, DCM/DMSO, −60 °C to r.t., overnight, and treatment with HCl; (d) o-phenylenediamine (1.0 equiv), pyridine, 65 °C. (ii) Carbazole (2.0 equiv), CuI (5%), o-C6H4Cl2, 180 °C. (iii) Phenothiazine (2.2 equiv), Pd2(dba)3 (5%), t-Bu3P, t-BuONa, toluene, reflux. (iv) Carbazole (1.0 equiv), CuI (5%), o-C6H4Cl2, 180 °C. (v) Phenothiazine (1.0 equiv), CuI (5%), o-C6H4Cl2, 180 °C. (vi) For Cz–BMes and Pz–BMes: Mes2BC6H4B(OH)2, Pd(PPh3)4 (5%), K2CO3, toluene/H2O, reflux. For Cz–Npa, Pz–Npa, Cz–NpaBr, and Pz–NpaBr: (a) benzophenonimine, Pd2(dba)3 (5%), BINAP, t-BuONa, 107 °C; (b) treatment with HCl and THF; (c) (bromo)naphthalic anhydride, HOAc, reflux, 5 h.

Single crystals of Cz–Cz and Pz–Pz were grown by slow evaporation from the CH2Cl2/MeOH solution (1:1, v/v) at room temperature, and their solid-state structures were examined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. As shown in Figure 1, the rigid backbone of these molecules was indicated by dihedral angles of 120° between the phenyl rings in triptycene. Different intermolecular interactions proved crucial to the molecular packing of these compounds. The assembly of Cz–Cz leads to an antiparallel superstructure via C–H···π interactions (2.790 and 2.898 Å), while the supramolecular structure of Pz–Pz is a result of the cooperative effects of C–H···π (2.822 and 2.826 Å), C–H···S interactions (3.417 Å), and π–π stacks (3.399 Å). This difference in the molecular packing may reflect the sterically nonplanar and more bulky nature of the electron donor Pz than that of Cz.

Figure 1.

X-ray crystallographic structures (left) and molecular packing (right) of Cz–Cz and Pz–Pz (50% thermal ellipsoids). Aromatic hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

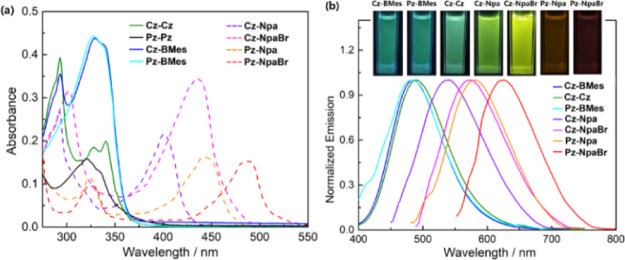

The photophysical properties of these compounds were investigated in CH2Cl2, and the results are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Figure 2a, Cz–Cz and Pz–Pz display moderate absorption bands around 350 nm in the UV–vis spectra, ascribed to change transfer from Cz–Pz to the triptycene core. In comparison, stronger charge transfer absorption was observed for other compounds due to the contribution from additional electron acceptors of BMes, Npa, and NpaBr, consistent with the TD-DFT computational data. With exception in Pz–Pz, these molecules show intense luminescence with reasonably high quantum efficiency (Φfl = 0.22–0.42, in CH2Cl2). More importantly, their emission colors were highly tunable over a broad spectrum from 485 nm (green) to 625 nm (red) as the electron-accepting strength of A moieties were systematically enhanced (Figure 2, inset). The solvent-induced solvatochromic shift in the emission was also observed (Figure S34). These optical behaviors suggest that the through-space electron coupling proves highly efficient in the homoconjugated triptycene-based systems used for emission modulation materials.

Table 1. Photophysical and Computational Data.

| λabsa (nm) | λema (nm) | Φflb (%) | EHOMOc (eV) | ELUMOc (eV) | Egapd (eV) | ETDDFTe (eV) | Egap(opt)f (eV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cz–Cz | 341 | 490 | 42 | –5.39 | –1.88 | 3.51 | 3.10 | 3.53 |

| Cz–BMes | 329 | 485 | 36 | –5.35 | –1.85 | 3.50 | 3.12 | 3.45 |

| Cz–Npa | 400 | 579 | 29 | –5.27 | –2.48 | 2.79 | 2.54 | 2.90 |

| Cz–NpaBr | 434 | 573 | 24 | –5.30 | –2.68 | 2.62 | 2.37 | 2.68 |

| Pz–Pz | 356 | N/A | N/A | –5.01 | –1.92 | 3.09 | 2.71 | 3.33 |

| Pz–BMes | 327 | 485 | 32 | –4.95 | –1.86 | 3.09 | 2.73 | 3.45 |

| Pz–Npa | 444 | 581 | 26 | –4.87 | –2.50 | 2.37 | 2.11 | 2.65 |

| Pz–NpaBr | 489 | 625 | 22 | –4.90 | –2.70 | 2.20 | 1.95 | 2.44 |

Recorded in CH2Cl2 (c = 1.0 × 10–5 M) for the longest λmax.

Fluorescence quantum efficiency (Φfl).

Obtained by DFT calculations (B3LYP, 6-31G*).

HOMO–LUMO energy gap: Egap = ELUMO – EHOMO.

Vertical excitation of the lowest transition (S0 → S1) calculated by TD-DFT (B3LYP, 6-31G**).

Calculated from the experimental absorption onset.

Figure 2.

(a) UV–vis absorption and (b) emission spectra recorded in CH2Cl2 (c = 1.0 × 10–5 M, λex = λabs(max)). Inset: photographs of emission colors for solutions under UV light at λex = 365 nm. The absence of Pz–Pz is due to its nonemissive nature in pure organic solvents.

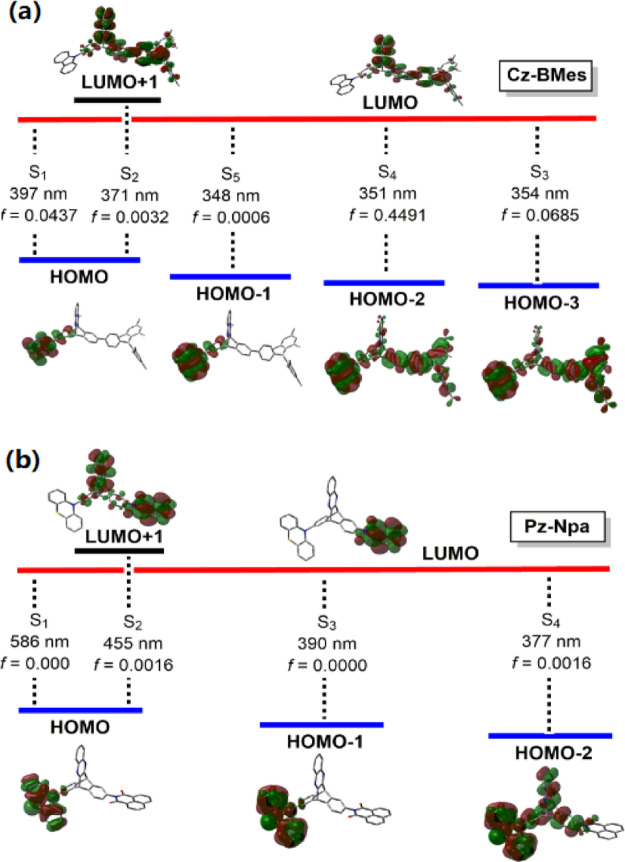

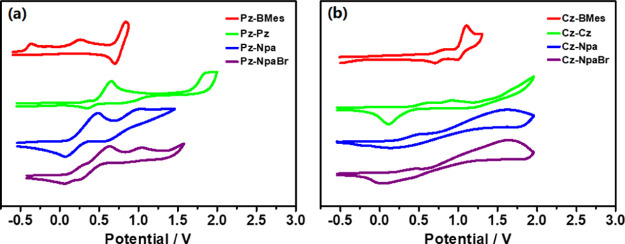

Using DFT (B3LYP/6-31G* and CAM-B3LYP/6-31G*) and TD-DFT (B3LYP/6-311G**), we performed their electronic structure calculations and the results are described in the Supporting Information. These molecules show similar HOMOs localized on electron donors Cz–Pz, and LUMOs involve the major acceptor moieties (BMes, Npa, and NpaBr) with contribution from the triptycene unit. Notably, the HOMOs are fully separated from LUMOs and have no overlap of the electron density in all cases. As illustrated for representative examples in Figure 3, vertical excitations to lower excited states (S1, S2) of Cz–BMes exhibit a CT character and π–π* transition is also observed in higher energy transitions (S0 → S3, f = 0.0685; S0 → S4, f = 0.4491). However, Pz–Npa shows only charge-transfer electronic transitions likely due to the high strength of the Npa acceptor (Figure 3b). The first electrochemical oxidation wave (vs Fc+/Fc, CH2Cl2) shifts more positive in cyclic and differential pulse voltammetry (CV and DPV) as the acceptors are incorporated in the molecular systems, indicative of again the electronic communications between the donor and acceptor across the homoconjugated triptycene (Figures 4 and S32).

Figure 3.

Vertical excitations, oscillator strength (f) (TD-DFT, B3LYP/6-31G**), and diagrams of the calculated orbitals contributing to key transitions (isovalue = 0.02; DFT, B3LYP/6-31G*) for Cz–BMes (a) and Pz–Npa (b) as representative examples.

Figure 4.

CV of oxidation curves for (a) Pz–Pz, Pz–BMes, Pz–Npa, and Pz–NpaBr; (b): Cz–Cz, Cz–BMes, Cz–Npa, and Cz–NpaBr (vs Fc+/Fc) recorded in CH2Cl2 with [Bu4N][PF6] (c = 0.1 M) as the electrolyte, ν = 100 mV/s.

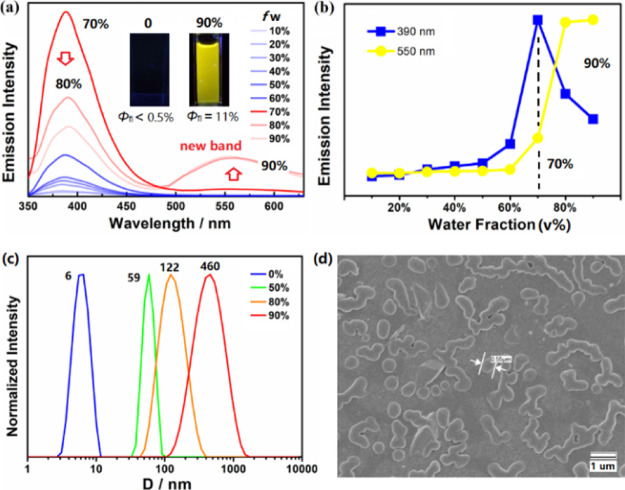

Given that Pz–Pz showed a nonemissive property in dilute solutions of pure organic solvents, in sharp contrast to other analogues, we explored its photoluminescence in aggregates. To examine the exceptional AIE behavior, its emission spectra were acquired in the mixture solvent (H2O/THF) with increasing water fractions (fw). As shown in Figure 5a, Pz–Pz exhibits very poor emission (Φfl < 0.5%), and the solution remains almost dark before the water fraction goes up to fw = 50%. A rapid increase in the emission was then observed at 390 nm, and an apparent turn-on fluorescence occurred with the loss of transparency of solutions. As further increase of the water content approaches fw = 90%, a strongly emissive solution was visualized together with a dramatically enhanced fluorescence quantum yield (Φfl = 11%) in response to the increase of solvent polarity (Figure 5a, inset). The enhanced emission of Pz–Pz is attributed to the formation of aggregated states, fully consistent with the well-known AIE activity. As evidenced by dynamic light scattering (DLS) profiles (Figure 5c), the average size of aggregated particles was fast growing with the hydrodynamic diameter (D) increasing from ∼6 nm for fw = 0% to 460 nm for fw = 90%. These aggregates were also confirmed by the particles of 0.55 μm displayed in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image (Figure 5d). This AIE property might be a result of cooperative effects from the 3D rigid geometry of triptycene and the bulky, twisted sterics of the Pz donor.

Figure 5.

AIE behavior of Pz–Pz: (a) emission spectra of solutions in H2O/THF with increasing water fraction (c = 1.0 × 10–5 M, λex = 356 nm); (b) intensity changes in the two emission bands (λem = 390 and 550 nm) at various fw; (c) selected DLS profiles as a function of fw and (d) SEM image (H2O/THF, fw = 90%).

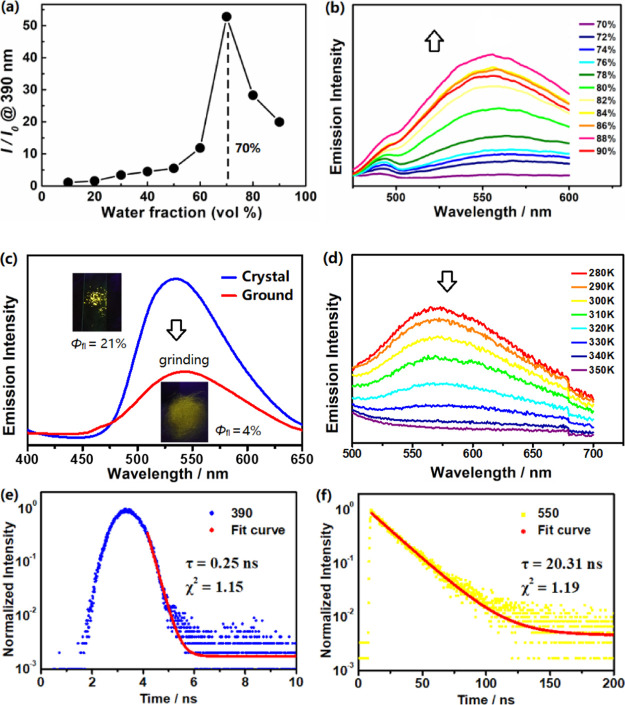

Interestingly, once fw exceeds 70%, further addition of water resulted in a remarkable decrease in emission of the initial band at 390 nm along with a highly red-shifted new broad emission band developed at 550 nm and gradually enhanced up to fw = 90% (Figures 5a,b and 6a,b). By comparison, the new band at 550 nm was similarly recorded for single crystals of Pz–Pz with a strong yellow emission (Φfl = 21%). We also found that grinding the crystals leads to a considerable emission quenching with the Φfl = 4% (Figure 6c). The variable temperature-dependent spectra indicated that the emission at 550 nm nearly disappeared when T was elevated to 350 K (Figure 6d). Based on these, we suspect that such a broad, highly bathochromically shifted (∼160 nm) and concentration-enhanced emission at 550 nm in aggregates and crystals could be similar to excimer-induced emission in the condensed states.17

Figure 6.

(a) Plot of I/I0 verse water fraction, I0 is the emission intensity in pure THF at 390 nm; (b) expansion of the new emission band developed at 550 nm with the water fraction ranging from 70 to 90% for Pz–Pz; (c) emission changes in response to mechanical force in the solid state of Pz–Pz. Inset: photographs of emission colors under the UV lamp (λex = 365 nm) before and after grinding the crystal; (d) temperature-dependent emission spectra at 550 nm for solution in H2O/THF (c = 1.0 × 10–5 M, fw = 85%, λex = 356 nm); (e,f) time-resolved fluorescence decay curves for Pz–Pz in H2O/THF monitored at λem = 390 and 550 nm.

To gain better understanding of the origin of dual emissions in Pz–Pz and support the excimer formation as a function of water fractions, we dissected its solid-state structural packing and spectroscopic analysis of the far-separated emissions at 390 and 550 nm assigned to the monomer and excimer, respectively. Compared with the Cz–Cz crystal structure, multiple types of intermolecular contacts (e.g. C–H···π, C–H···S, and π–π stacking) involved in Pz–Pz further strengthen the dimeric stabilization, in favor of the existence of the excimer in condensed states. A drop in the emission at 390 nm and an increment at 550 nm were the consequence of the increased molar ratio of the excimer/monomer upon fw > 70%. The excitation spectra monitored at the two emissions also show similar profiles, indicating a relationship of the precursor-successor between the monomer and excimer (Figure S36). Furthermore, the time-resolved emission decay of the longer-lived excited state at 550 nm gave a lifetime τav = 20.3 ns (Figure 6e,f), which is 80 times greater than that of τav = 0.25 ns for λem = 390 nm and is typically observed in excimer formation.17c,17d

Conclusions

In this work, we have designed and synthesized a series of triptycene-based D–A type luminescent materials. The use of intrinsically rigid and spatially disposed triptycene as an unusual steric spacer gave rise to new through-space charge-transfer molecular systems, resulting from the homoconjugation effect of the central triptycene core. These molecules are highly emissive, and the emission modulation was achieved over a wide range of 390–625 nm by fine tuning the electron-accepting strength (e.g. BMes, Npa, and NpaBr). Pz–Pz represents a new example of triptycene-based AIE molecules, and its emission was switched on by addition of water leading to aggregated excited states. The solid-state yellow emission showed pronounced changes in response to the mechanical stimulus. We envision that these triptycene derivatives may provide a new platform for future studies of high-performance luminescent materials with applications in sensing and electronic devices.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (no. 21772012). We also thank the Analysis and Testing Centre at the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) for all facilities.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03565.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Ostroverkhova O. Organic Optoelectronic Materials: Mechanisms and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13279–13412. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li R.; Xiao S.; Li Y.; Lin Q.; Zhang R.; Zhao J.; Yang C.; Zou K.; Li D.; Yi T. Polymorphism-dependent and piezochromic luminescence based on molecular packing of a conjugated molecule. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 3922–3928. 10.1039/c4sc01243g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Li R.; Wang S.; Li Q.; Lan H.; Xiao S.; Li Y.; Tan R.; Yi T. A fluorescent non-conventional organogelator with gelation-assisted piezochromic and fluoride-sensing properties. Dyes Pigments 2017, 137, 111–116. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Gao H.; Zhang X.; Chen C.; Li K.; Ding D. Unity Makes Strength: How Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens Advance the Biomedical Field. Adv. Biosyst. 2018, 2, 1800074. 10.1002/adbi.201800074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Huang H.; Zhou Y.; Wang M.; Zhang J.; Cao X.; Wang S.; Cao D.; Cui C. Regioselective Functionalization of Stable BN-Modified Luminescent Tetraphenes for High-Resolution Fingerprint Imaging. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10132–10137. 10.1002/anie.201903418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Brédas J.-L.; Beljonne D.; Coropceanu V.; Cornil J. Charge-Transfer and Energy-Transfer Processes in π-Conjugated Oligomers and Polymers: A Molecular Picture. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4971–5004. 10.1021/cr040084k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Müllen K.; Pisula W. Donor–Acceptor Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9503–9505. 10.1021/jacs.5b07015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Data P.; Pander P.; Okazaki M.; Takeda Y.; Minakata S.; Monkman A. P. Dibenzo[a, j]phenazine-Cored Donor-Acceptor-Donor Compounds as Green-to-Red/NIR Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Organic Light Emitters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5739–5744. 10.1002/anie.201600113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Batra A.; Kladnik G.; Vázquez H.; Meisner J. S.; Floreano L.; Nuckolls C.; Cvetko D.; Morgante A.; Venkataraman L. Quantifying through-space charge transfer dynamics in π-coupled molecular systems. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1086. 10.1038/ncomms2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li J.; Shen P.; Zhao Z.; Tang B. Z. Through-Space Conjugation: A Thriving Alternative for Optoelectronic Materials. CCS Chem. 2019, 1, 181–196. 10.31635/ccschem.019.20180020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Jiang X.; Rodríguez-Molina B.; Nazarian N.; Garcia-Garibay M. A. Rotation of a Bulky Triptycene in the Solid State: Toward Engineered Nanoscale Artificial Molecular Machines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8871–8874. 10.1021/ja503467e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang G.-W.; Li P.-F.; Meng Z.; Wang H.-X.; Han Y.; Chen C.-F. Triptycene-Based Chiral Macrocyclic Hosts for Highly Enantioselective Recognition of Chiral Guests Containing a Trimethylamino Group. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5304–5308. 10.1002/anie.201600911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Han Y.; Meng Z.; Ma Y.-X.; Chen C.-F. Iptycene-Derived Crown Ether Hosts for Molecular Recognition and Self-Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2026–2040. 10.1021/ar5000677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chen C.-F.; Han Y. Triptycene-Derived Macrocyclic Arenes: From Calixarenes to Helicarenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2093–2106. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Li P.; Li P.; Ryder M. R.; Liu Z.; Stern C. L.; Farha O. K.; Stoddart J. F. Interpenetration Isomerism in Triptycene-Based Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1664–1669. 10.1002/anie.201811263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Ishiwari F.; Nascimbeni G.; Sauter E.; Tago H.; Shoji Y.; Fujii S.; Kiguchi M.; Tada T.; Zharnikov M.; Zojer E.; Fukushima T. Triptycene Tripods for the Formation of Highly Uniform and Densely Packed Self-Assembled Monolayers with Controlled Molecular Orientation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5995–6005. 10.1021/jacs.9b00950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ferguson L. N.; Nnadi J. C. Electronic interactions between nonconjugated groups. J. Chem. Educ. 1965, 42, 529. 10.1021/ed042p529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kobayashi T.; Kubota T.; Ezumi K. Intramolecular orbital interactions in triptycene studied by photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 2172–2174. 10.1021/ja00346a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Harada N.; Uda H.; Nakasuji K.; Murata I. Interchromophoric Homoconjugation Effect and Intramolecular Charge-transfer Transition of the Triptycene System Containing a Tetracyanoquinodimethane Chromophore. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1989, 1449–1453. 10.1039/p29890001449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Menke E. H.; Lami V.; Vaynzof Y.; Mastalerz M. π-Extended Rigid Triptycene-Trisaroylenimidazoles as Electron Acceptors. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 1048–1051. 10.1039/c5cc07238g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasumi K.; Wu T.; Zhu T.; Chae H. S.; Van Voorhis T.; Baldo M. A.; Swager T. M. Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Materials Based on Homoconjugation Effect of Donor–Acceptor Triptycenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11908–11911. 10.1021/jacs.5b07932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ikai T.; Yoshida T.; Shinohara K.-i.; Taniguchi T.; Wada Y.; Swager T. M. Triptycene-Based Ladder Polymers with One-Handed Helical Geometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4696–4703. 10.1021/jacs.8b13865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ikai T.; Yoshida T.; Awata S.; Wada Y.; Maeda K.; Mizuno M.; Swager T. M. Circularly Polarized Luminescent Triptycene-Based Polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 364–369. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.8b00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhelev Z.; Ohba H.; Bakalova R. Single Quantum Dot-Micelles Coated with Silica Shell as Potentially Non-Cytotoxic Fluorescent Cell Tracers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6324–6325. 10.1021/ja061137d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bakalova R.; Zhelev Z.; Aoki I.; Ohba H.; Imai Y.; Kanno I. Silica-Shelled Single Quantum Dot Micelles as Imaging Probes with Dual or Multimodality. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 5925–5932. 10.1021/ac060412b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.; Xie Z.; Lam J. W. Y.; Cheng L.; Tang B. Z.; Chen H.; Qiu C.; Kwok H. S.; Zhan X.; Liu Y.; Zhu D. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1740–1741. 10.1039/b105159h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mei J.; Leung N. L. C.; Kwok R. T. K.; Lam J. W. Y.; Tang B. Z. Aggregation-Induced Emission: Together We Shine, United We Soar!. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11718–11940. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hong Y.; Lam J. W. Y.; Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5361–5388. 10.1039/c1cs15113d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kwok R. T. K.; Leung C. W. T.; Lam J. W. Y.; Tang B. Z. Biosensing by luminogens with aggregation-induced emission characteristics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4228–4238. 10.1039/c4cs00325j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ding D.; Li K.; Liu B.; Tang B. Z. Bioprobes Based on AIE Fluorogens. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2441–2453. 10.1021/ar3003464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li K.; Liu B. Polymer-Encapsulated Organic Nanoparticles for Fluorescence and Photoacoustic Imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6570–6597. 10.1039/c4cs00014e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Feng G.; Liu B. Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) Dots: Emerging Theranostic Nanolights. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1404–1414. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hu F.; Xu S.; Liu B. Photosensitizers with Aggregation-Induced Emission: Materials and Biomedical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801350. 10.1002/adma.201801350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu S.; Yuan Y.; Cai X.; Zhang C.-J.; Hu F.; Liang J.; Zhang G.; Zhang D.; Liu B. Tuning the Singlet-Triplet Energy Gap: A Unique Approach to Efficient Photosensitizers with Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) Characteristics. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5824–5830. 10.1039/c5sc01733e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu J.; Chen C.; Ji S.; Liu Q.; Ding D.; Zhao D.; Liu B. Long Wavelength Excitable Near-Infrared Fluorescent Nanoparticles with Aggregation-Induced Emission Characteristics for Image-Guided Tumor Resection. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2782–2789. 10.1039/c6sc04384d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ni J. S.; Min T.; Li Y.; Zha M.; Zhang P.; Ho C. L.; Li K. Planar AIEgens with Enhanced Solid-State Luminescence and ROS Generation for Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Treatment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10179–10185. 10.1002/anie.202001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a An B.-K.; Gierschner J.; Park S. Y. π-Conjugated Cyanostilbene Derivatives: A Unique Self-Assembly Motif for Molecular Nanostructures with Enhanced Emission and Transport. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 544–554. 10.1021/ar2001952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sinha N.; Stegemann L.; Tan T. T. Y.; Doltsinis N. L.; Strassert C. A.; Hahn F. E. Turn-On Fluorescence in Tetra-NHC Ligands by Rigidification through Metal Complexation: An Alternative to Aggregation-Induced Emission. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2785–2789. 10.1002/anie.201610971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen J. F.; Yin X.; Wang B.; Zhang K.; Meng G.; Zhang S.; Shi Y.; Wang N.; Wang S.; Chen P. Planar Chiral Organoboranes with Thermoresponsive Emission and Circularly Polarized Luminescence: Integration of Pillar[5]arenes with Boron Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11267–11272. 10.1002/anie.202001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ji G.; Wang N.; Yin X.; Chen P. Substituent Effect Induces Emission Modulation of Stilbene Photoswitches by Spatial Tuning of the N/B Electronic Constraints. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5758–5762. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu Q.; Wang S.; Chen P. Diazocine Derivatives: A Family of Azobenzenes for Photochromism with Highly Enhanced Turn-On Fluorescence. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 4025–4029. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chen J.-F.; Meng G.; Zhu Q.; Zhang S.; Chen P. Pillar[5]arenes: A New Class of AIEgen Macrocycles Used for Luminescence Sensing of Fe3+ Ions. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 11747–11751. 10.1039/c9tc03831k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Chen J.-F.; Chen P. Pillar[5]arene-Based Resilient Supramolecular Gel with Dual-Stimuli Responses and Self-Healing Properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 2224–2229. 10.1021/acsapm.9b00516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Shi Y.-g.; Mellerup S. K.; Yuan K.; Hu G.-F.; Sauriol F.; Peng T.; Wang N.; Chen P.; Wang S. Stabilising Fleeting Intermediates of Stilbene Photocyclization with Amino-borane Functionalisation: the Rare Isolation of Persistent Dihydrophenanthrenes and Their [1,5] H-shift Isomers. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3844–3855. 10.1039/c8sc00560e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Hou Q.; Liu L.; Mellerup S. K.; Wang N.; Peng T.; Chen P.; Wang S. Stimuli-Responsive B/N Lewis Pairs Based on the Modulation of B-N Bond Strength. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 6467–6470. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Chen P.; Yin X.; Baser-Kirazli N.; Jäkle F. Versatile Design Principles for Facile Access to Unstrained Conjugated Organoborane Macrocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10768–10772. 10.1002/anie.201503219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Chen P.; Li Q.; Grindy S.; Holten-Andersen N. White-Light-Emitting Lanthanide Metallogels with Tunable Luminescence and Reversible Stimuli-Responsive Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11590–11593. 10.1021/jacs.5b07394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Thapaliya E. R.; Swaminathan S.; Captain B.; Raymo F. M. Autocatalytic Fluorescence Photoactivation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13798–13804. 10.1021/ja5068383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen Z.; Bouffard J.; Kooi S. E.; Swager T. M. Highly Emissive Iptycene-Fluorene Conjugated Copolymers: Synthesis and Photophysical Properties. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 6672–6676. 10.1021/ma800486a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kim Y.; Bouffard J.; Kooi S. E.; Swager T. M. Highly Emissive Conjugated Polymer Excimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13726–13731. 10.1021/ja053893+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu Y.; Tao X.; Wang F.; Shi J.; Sun J.; Yu W.; Ren Y.; Zou D.; Jiang M. Intermolecular Hydrogen Bonds Induce Highly Emissive Excimers: Enhancement of Solid-State Luminescence. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 6544–6549. 10.1021/jp070288f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Chen Y.-H.; Tang K.-C.; Chen Y.-T.; Shen J.-Y.; Wu Y.-S.; Liu S.-H.; Lee C.-S.; Chen C.-H.; Lai T.-Y.; Tung S.-H.; Jeng R.-J.; Hung W.-Y.; Jiao M.; Wu C.-C.; Chou P.-T. Insight Into the Mechanism and Outcoupling Enhancement of Excimer-Associated White Light Generation. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3556–3563. 10.1039/c5sc04902d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Suk J.; Wu Z.; Wang L.; Bard A. J. Electrochemistry, Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence, and Excimer Formation Dynamics of Intramolecular π-Stacked 9-Naphthylanthracene Derivatives and Organic Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14675–14685. 10.1021/ja203731n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.