Abstract

Flowering time and mating system divergence are two of the most common adaptive transitions in plants. We review recent progress toward understanding the genetic basis of these adaptations in new model plant species. For flowering time, we find that individual crosses often reveal a simple genetic basis, but that the loci involved almost always vary within species and across environments, indicating a more complex genetic basis species-wide. Similarly, the transition to self-fertilization is often genetically complex, but this seems to depend on the amount of standing variation and time since species divergence. Recent population genomic studies also raise doubts about the long-term adaptive potential of self-fertilization, providing evidence that purifying selection is less effective in highly selfing species.

Introduction

Heterogeneity across the natural landscape provides a rich substrate for adaptation among plant populations. Reciprocal transplant experiments in numerous taxa have shown that plants are strongly adapted to their local environments [1,2], and this may be particularly true with regards to traits that influence the timing [3,4] or system of reproduction. In recent years, studies of wild plant systems, many of which are highly tractable for field experiments, have made significant strides toward identifying the genetic architecture of ecologically important adaptive shifts. In addition to addressing the question of whether adaptive traits diverge by major or minor steps, these studies have begun to address fundamental questions about the repeatability of evolutionary transitions. In this review, we focus on progress from these new models on the genetics of two traits that are also important axes of adaptive divergence between plant populations and species: flowering time and mating system. For both of these key quantitative traits, we highlight the strong influence of complex environments on their evolution. For example, even when flowering time loci have major phenotypic effects, they are often polymorphic and only locally distributed within species. We also point to differences in the origin of mating system transitions that may affect genetic architecture. Lastly, we discuss new studies that indicate a shift in mating system (i.e., from outcrossing to self-fertilization) may limit the long-term adaptive potential of affected plant lineages. We conclude by underscoring the need for quantitative genetics field experiments across the native ranges of plant populations and species that differ in flowering behavior and mating system.

Genetic basis of divergence in flowering phenology, a key component of local adaptation

In angiosperms, the initiation of flowering is a complex trait that is highly dependent on edaphic and climatic conditions, with the decision to flower regulated by an integrated genetic network responding to both autonomous signals and environmental cues [5]. The timing of reproduction is critically important for plant fitness, and natural selection can optimize flowering phenology to coincide with locally favorable conditions. Over evolutionary time, this process leads to divergence among plant populations in how they respond to the length of winter (vernalization), temperature, photoperiod, and/or nutrient levels [6•,7,8••]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, studies of natural accessions have identified a number of genes that contribute to quantitative variation in flowering time [9,10], but until quite recently, little was known about the genetic basis of flowering phenotypes in other wild plant species.

One of the more striking results to emerge from studies of new plant model systems is the degree to which genes for flowering behavior are influenced by complex natural environments. In Boechera stricta, a perennial relative of A. thaliana found along a broad elevational gradient in the Rocky Mountains, recombinant inbred lines grown under field and controlled laboratory conditions display dramatically different flowering times and utilize distinct sets of quantitative trait loci (QTL) to initiate reproduction [11]. Similarly, in crosses between diverged populations of the perennial Arabidopsis lyrata [12], flowering time QTL identified in greenhouse and field environments are not identical (a disconnect between laboratory and field QTL has also been seen in A. thaliana [13]). These studies have led to awareness that, going forward, field experiments in species’ native habitats will be critical for determining the genetic basis of adaptation in ecologically relevant contexts.

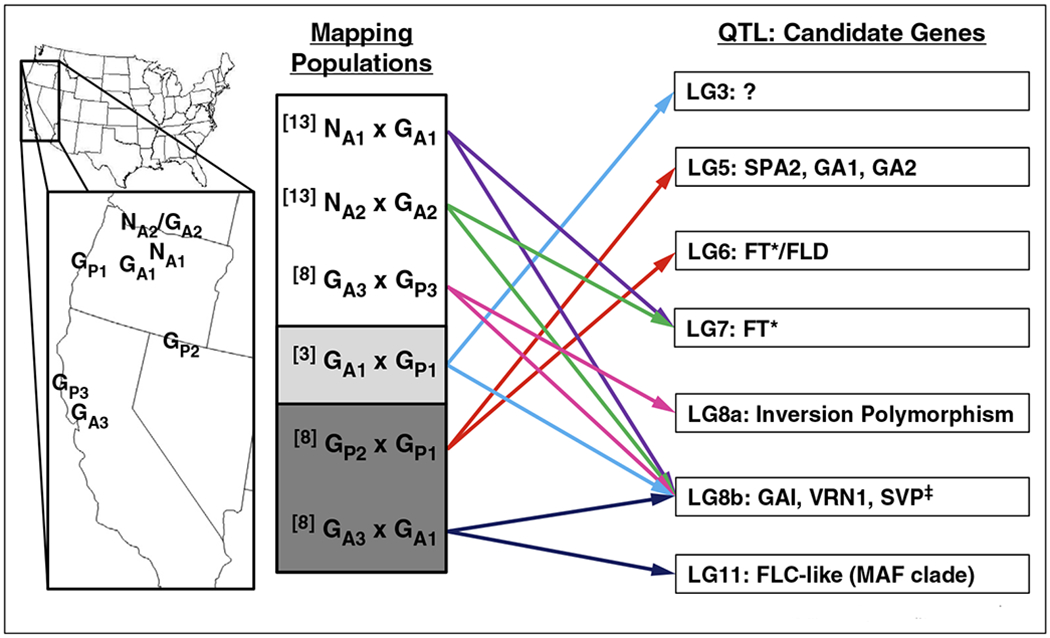

A number of recent studies in diverse plant taxa have detected loci with major effects on flowering time divergence among natural populations. Many of these same loci also co-localize with genes from the flowering time network. In B. stricta, variation in flowering time is partly explained by a major-effect QTL centered on the genomic region containing an ortholog of the Arabidopsis floral integrator gene FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) [14]. Similarly, an ortholog of another key flowering time gene, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) underlies the vernalization requirement for flowering Arabis alpina, an arcticalpine perennial crucifer [6•,12]. QTL mapping in the yellow monkeyflowers of the Mimulus guttatus species complex has also detected loci with major effects on flowering responses to both critical photoperiod and vernalization (Figure 1, [8••,15••]). Members of the M. guttatus group vary widely in life history (small, selfing, and facultatively annual to large and perennial), and occupy diverse habitats across a range of elevations and latitudes. For the highly selfing M. nasutus, which is often found in drier microhabitats where it co-occurs with M. guttatus [16], early flowering is likely an adaptive strategy to avoid drought [17,18]. Flowering time variation between these two Mimulus species is almost entirely explained by only two QTL, suggesting that this evolutionary transition to short-day flowering may have occurred rapidly [15••]. Interestingly, a simple genetic architecture for flowering time divergence also appears to be the rule in A. thaliana: only a handful of loci explain much of the variation in flowering behavior across a diverse collection of accessions [10].

Figure 1.

Variation in the genetic basis of flowering time behavior within and between Mimulus species. Major effect QTL for flowering time in Mimulus were identified in three QTL mapping studies performed in the greenhouse [15,19] or growth chambers [8••]. The map shows collection sites for parental lines used in mapping experiments (NA2/GA2 is a sympatric site). Crosses indicate annual M. guttatus (GA), perennial M. guttatus (GP), or annual M. nasutus (NA), with numbers corresponding to distinct parental lines. Shading indicates flowering cue being tested: no shading = critical photoperiod, light grey = long-day flowering, and dark-grey = vernalization requirement under long days. Only two major effect QTL were identified in each population (colored arrows), indicating a simple genetic basis. QTL (linkage group: candidate genes) are listed on right. Notice that some QTL (LG7 and LG8b) are observed in multiple crosses, whereas all others vary with genotype and/or environment. Candidate genes: SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA 2 (SPA2), GIBBERELIC ACID REQUIRING 1 (GA1), GIBBERELLIC ACID REQUIRING 2 (GA2), FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), GIBBERELLIC ACID INSENSITIVE (GAI), VERNALIZATION1 (VRN1), SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP), FLOWERING LOCUS D (FLD), FLOWERINC LOCUS C (FLC), MADS-BOX AFFECTING (MAF). *The M. guttatus reference genome contains 8 full/partial copies of FT. ‡Three paralogous copies of SVP underlie this QTL.

At the same time that major effect mutations have been found in individual crosses, it has become clear that flowering behavior at a species-wide scale might often be genetically heterogeneous. In Mimulus, unique sets of QTL for short-day flowering have been mapped in each of six distinct crosses between ecotypes [8••,19] and species [15••], suggesting that this parallel transition does not always share a common genetic basis (Figure 1). Of the few QTL that have been identified in multiple Mimulus crosses, one spans a genomic region with several flowering time candidates [8••,15••], including three copies of SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP) family genes; in A. thaliana, functional copies of SVP repress FT to prevent short-day flowering, whereas nonfunctional alleles confer short-day flowering [20]. The phenotypic effects of this common QTL appear to differ among parental lines of Mimulus (it has been mapped alternately as a vernalization and critical photoperiod QTL) [8••,15••], consistent with the idea that it is underlain by multiple independent alleles, as was recently discovered for several flowering time QTL in A. thaliana [10]. Similarly, in the perennial A. alpina, natural accessions that lack a vernalization requirement carry different loss-of-function mutations in the same FLC ortholog (PERPETUAL FLOWERING 1), implying at least five evolutionary origins of this flowering phenotype [6•]. Although for most plant systems the molecular variants that contribute to natural variation in flowering behavior have not yet been identified, it is clear that flowering time loci often vary within species. A key question for future studies is if local adaptation to specific habitats limits the geographic distribution of particular flowering time alleles.

Genetic basis of mating system evolution

Like flowering time, mating system is a key determinant of plant fitness and can also contribute to reproductive isolation between species [21]. Additionally, mating system divergence sometimes occurs across similar environmental gradients and/or is coincident with shifts in flowering time (e.g., early flowering, highly selfing M. nasutus typically inhabits drier habitats than outcrossing M. guttatus [16]). The shift from outcrossing to self-fertilization is perhaps the most frequent evolutionary transition in angiosperms [22,23]. Natural selection may favor the evolution of selfing for several reasons, including its ability to provide reproductive assurance, improve colonization ability, and increase allele transmission (see [24]). Reductions in flower size, flower number, antherstigma separation, and pollen/ovule ratio often accompany mating system shifts [25,26], but whether these phenotypic changes precede or follow the evolution of selfing is often unclear. In a handful of systems — particularly Mimulus and Capsella — complementary genetic mapping experiments and population genomic analyses are beginning to reveal new details about the tempo and dynamics of mating system evolution.

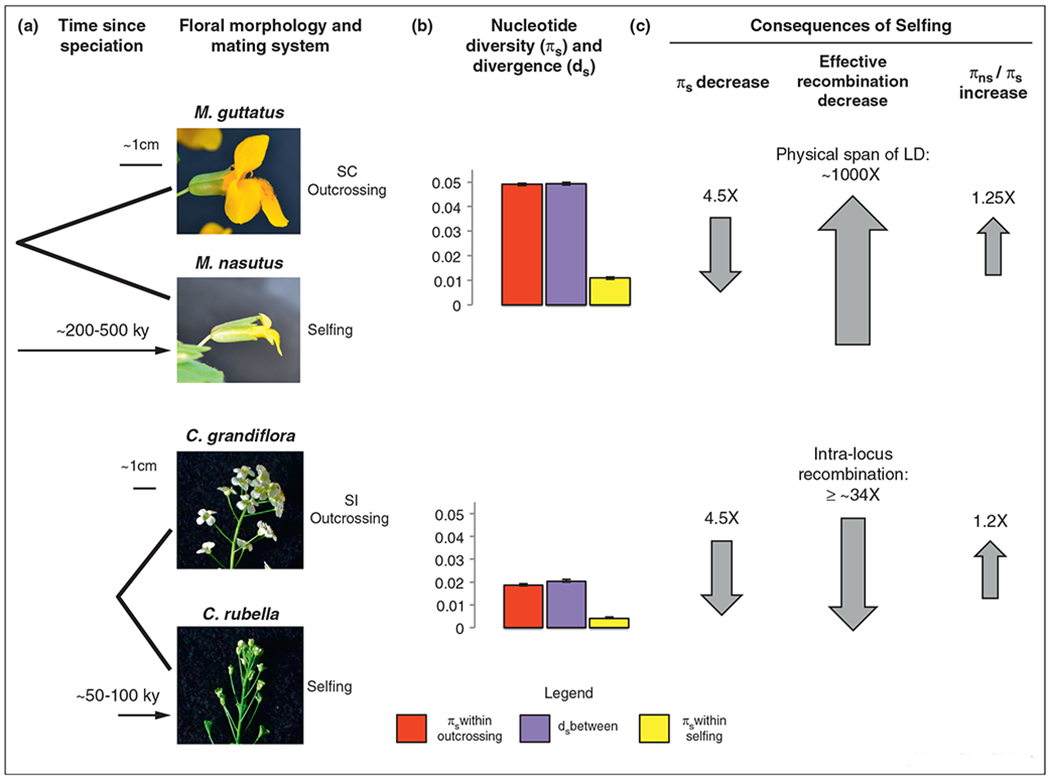

Several QTL mapping studies in diverse systems including Mimulus [27], Leptosiphon [28], and wild Oryza [29] suggest that traits distinguishing selfing and outcrossing species are generally due to many genes of small to moderate effect. In Mimulus, the evidence is particularly striking: 11–15 QTL contribute to each floral trait measured between the highly selfing M. nasutus and the predominantly outcrossing M. guttatus, with the vast majority accounting for only minor phenotypic effects [27]. In contrast to these studies, recent work in Capsella (a close relative of Arabidopsis) suggests that floral traits associated with mating system divergence can sometimes involve relatively few genes of large effect [30,31••]. Differences in flower size and stamen/style length between the highly selfing Capsella rubella and the self-incompatible C. grandiflora are due to only 2–5 QTL, with most explaining greater than 25% of the species difference [31••]. Why this difference in the genetic architecture of floral traits between Mimulus and Capsella? One simple explanation might be the timing of species divergence: M. nasutus evolved from M. guttatus roughly two hundred thousand years ago (Brandvain et al., unpublished data), whereas C. rubella evolved from C. grandiflora about fifty thousand years ago [32,33••,34] (Figure 2). Perhaps Capsella species have not yet had sufficient time to accumulate a comparable number of minor-effect substitutions.

Figure 2.

Recent speciation and the genomic consequences of mating system divergence in young species pairs of Mimulus and Capsella. (a) Speciation occurred recently and was associated with a transition to selfing and floral divergence in both species pairs ([32,33••,34], Brandvain et al., unpublished data). M. nasutus evolved from self-compatible, predominantly outcrossing M. guttatus, while C. rubella evolved from self-incompatible C. grandiflora. (b) M. guttatus, M. nasutus’ likely ancestor, contains more than twice the level of synonymous nucleotide diversity than C. grandiflora, the progenitor of C. rubella (Brandvain et al., unpublished data, [33••]). Levels of nucleotide divergence are similar to nucleotide diversity within the outcrossing species in both species pairs. (c) The evolution of selfing in Mimulus and Capsella resulted in proportional reductions in genomic variation and increases in putatively deleterious variation (Brandvain et al., unpublished data, [33••]), as well as extreme reductions in effective recombination (Brandvain et al., unpublished data, [32]). The upper and lower arrows represent genomic changes in the highly selfing M. nasutus relative to M. guttatus, and the highly selfing C. rubella relative to C. grandiflora, respectively. Because the median intra-locus recombination estimate was zero in C. rubella, the ratio of effective recombination was calculated using the median in C. grandiflora (0.131) and the mean in C. rubella (0.0038); the ratio is >65× if calculated using the mean in C. grandiflora (0.26).

Photo credits: Mimulus: Andrea L. Sweigart. Capsella: Young Wha Lee and Gavin Douglas.

Another, non-mutually exclusive possibility is that Capsella and Mimulus have taken different routes to self-fertilization. Distinct genetic architectures might reflect fundamental differences between selfing species that arise through the loss of self-incompatibility systems (e.g., Capsella) and those that evolve when self-compatible populations shift from predominant outcrossing to autonomous selfing (e.g., Mimulus, Leptosiphon, Oryza). In the former case, the evolution of selfing might be relatively rapid, particularly if there is also strong selection due to mate limitation. Indeed, in C. rubella, it appears that the evolution of self-compatibility was likely due to fixation of a single nonfunctional S-locus haplotype that was segregating within C. grandiflora [34,35]. On the other hand, the tempo of mating system evolution may proceed more slowly when selfing evolves through a gradual increase in inbreeding from a self-compatible ancestor like M. guttatus. Moreover, because selfing rates often vary considerably among populations of self-compatible species, these groups might carry more standing genetic variation for key floral traits than do self-incompatible species. There is abundant genetic variation for mating system traits within M. guttatus populations [36]. Also, genomic diversity at synonymous sites is nearly twice as high in M. guttatus as it is in C. grandiflora (Figure 2, [33••,37••], Brandvain et al., unpublished data).

Of course, a key question for these plant systems is what factors cause the initial evolution of self-fertilization. Extreme reductions in genomic diversity (i.e., beyond what is expected as a result of the 50% drop in effective population size associated with selfing [38]) in the selfing species of Mimulus and Capsella (Figure 2, [33••,37••], Brandvain et al., unpublished data) suggest that reproductive assurance may have been involved. The idea is that after a population bottleneck — perhaps due to demographic expansion — self-fertilization ensures that plants produce seeds even when pollinators and/or potential mates are rare. In Mimulus, pollen limitation experiments in the field [39] and greenhouse [36] have shown natural selection for reduced floral morphology, providing further support for a role for reproductive assurance. A related issue is whether ecological adaptation facilitates the evolution of selfing, or vice versa. If smaller flowers are favored in resource-limited environments, for example, self-fertilization might evolve after the reduction of floral structures — for reproductive assurance in the absence of pollinators and/or because anthers and stigmas are now in closer proximity. Alternatively, if selfing evolves first, a reduction in flower size may optimize fertilization efficiency or resource allocation, allowing selfing species to colonize marginal environments. Distinguishing between these scenarios will require field experiments that investigate the fitness effects of particular floral traits and QTL across native habitats.

Long-term consequences of self-fertilization

Despite the short-term advantages of selfing, and its role in promoting ecological divergence and speciation [40,41], new studies suggest that the long-term genomic consequences of inbreeding may ultimately limit the evolutionary potential of selfing lineages. In addition to halving the effective population size (Ne) and reducing effective recombination, selfing can further decrease Ne due to a combination of founding events, demographic stochasticity and/or linked selection (reviewed in [42]). Consistent with these predictions, recent analyses have discovered dramatic reductions in nucleotide variation in several young, highly selfing taxa including C. rubella [32,33••,37••], Clarkiaxantiana ssp. parviflora [43], Collinsia rattanii [44•], Mimulus nasutus (Brandvain et al., unpublished data), and one selfing lineage of Leavenworthia alabamica [45].

Low Ne in selfing species is predicted to reduce the efficacy of purifying selection (see [42]), but empirical support for this idea has been lacking [46]. New genomewide studies have found strong evidence that selfing populations/species accumulate more putatively deleterious alleles than their outcrossing relatives. For example, C. rubella [33••,37••], C. rattanii [44•], M. nasutus (Brandvain et al., unpublished data), and selfing populations of Eucalyptus paniculata [47] all contain elevated ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous nucleotide variation. Strikingly, M. nasutus carries 30% more premature stop codons than its sister species M. guttatus (Brandvain et al., unpublished data). Studies in C. rubella [32,33••,37••] and M. nasutus (Brandvain et al., unpublished data) particularly illustrate how long-term reductions in Ne and effective recombination may increase genetic drift and/or linked selection, and drive down the efficacy of purifying selection (Figure 2).

Although these studies suggest a rather negative outlook for selfing species, consistent with recent evidence for greater rates of extinction in selfing vs. outcrossing lineages [41], more research is needed to fully understand the complex consequences of selfing on genomic variation. For example, it is not clear to what extent the lower nucleotide diversity in selfing species reflects a general reduction in additive genetic variation [48,49], which is what might limit the potential for selfing lineages to respond to selection [50]. Additionally, we do not yet know the true fitness effects in selfing species of what are assumed to be deleterious alleles (i.e., non-synonymous mutations and premature stop codons), or where these fall on the spectrum between a healthy plant and complete genetic degradation. Moreover, non-synonymous variants in selfing species may reflect a release from selective constraint, instead of a reduction in the efficacy of purifying selection per se. Another possibility is that selfing could mitigate potentially deleterious processes that occur in outcrossing species (e.g., the effect of GC conversion bias on preferred codon use and proliferation of selfish genetic elements), but these effects need to be quantified [51]. Finally, low levels of introgression from outcrossing species into their selfing relatives (e.g., as in M. nasutus, Brandvain et al., unpublished data) may contribute additional genetic variation and/or limit the extent of deleterious allele accumulation in selfing species.

Conclusions

Our understanding of the genetic basis of adaptive traits is rapidly expanding and we can now begin to explore the evolutionary forces that affect individual loci in nature. A major question remains regarding the role of locally adapted genes in ongoing divergence. If QTL for flowering time or mating system traits exhibit fitness tradeoffs between different environments, they should remain distinct between populations connected by some gene flow, and thus contribute to population divergence and speciation. Field studies, in combination with genetic dissection of parallel phenotypic changes, will elucidate whether heterogeneity in the genes and/or alleles underlying divergence is due to selection favoring certain loci in different environments. Moreover, integrating the genetic basis of adaptation with population genomics will improve our understanding of the forces acting during and after major evolutionary transitions.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Leimu R, Fischer M: A meta-analysis of local adaptation in plants. PLoS ONE 2008, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hereford J: A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. Am Nat 2009, 173:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall MC, Lowry DB, Willis JH: Is local adaptation in Mimulus guttatus caused by trade-offs at individual loci? Mol Ecol 2010, 19:2739–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhoeven KJF, Poorter H, Nevo E, Biere A: Habitat-specific natural selection at a flowering-time QTL is a main driver of local adaptation in two wild barley populations. Mol Ecol 2008, 17:3416–3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andres F, Coupland G: The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13:627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.•.Albani MC, Castaings L, Wotzel S, Mateos JL, Wunder J, Wang RH, Reymond M, Coupland G: PEP1 of Arabis alpina is encoded by two overlapping genes that contribute to natural genetic variation in perennial flowering. PLoS Genet 2012, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper indicates that the PEP1 gene in Arabis alpina has been repeatedly targeted by selection on flowering time variation. In most cases variation appears to be due to gene duplication – indicating a possible role for gene duplication in the evolution of adaptive traits.

- 7.Grillo MA, Li CB, Hammond M, Wang LJ, Schemske DW: Genetic architecture of flowering time differentiation between locally adapted populations of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 2013, 197:1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.••.Friedman J, Willis JH: Major QTLs for critical photoperiod and vernalization underlie extensive variation in flowering in the Mimulus guttatus species complex. New Phytol 2013, 199:571–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors of this paper present a comprehensive assessment of flowering time variation in an ecologically diverse panel of populations and species in the Mimulus guttatus complex. In addition, they identify major-effect QTL for vernalization requirement and critical photoperiod among ecotypes of M. guttatus, with unique QTL explaining differences in vernalization requirement in different crosses.

- 9.Shindo C, Aranzana MJ, Lister C, Baxter C, Nicholls C, Nordborg M, Dean C: Role of FRIGIDA and FLOWERING LOCUS C in determining variation in flowering time of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2005, 138:1163–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salome PA, Bomblies K, Laitinen RAE, Yant L, Mott R, Weigel D: Genetic architecture of flowering-time variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 2011, 188:421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leinonen PH, Remington DL, Leppala J, Savolainen O: Genetic basis of local adaptation and flowering time variation in Arabidopsis lyrata. Mol Ecol 2013, 22:709–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang RH, Farrona S, Vincent C, Joecker A, Schoof H, Turck F, Alonso-Blanco C, Coupland G, Albani MC: PEP1 regulates perennial flowering in Arabis alpina. Nature 2009, 459:423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brachi B, Faure N, Horton M, Flahauw E, Vazquez A, Nordborg M, Bergelson J, Cuguen J, Roux F: Linkage and association mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana flowering time in nature. PLoS Genet 2010, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson JT, Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T: Life-history Qtls and natural selection on flowering time in Boechera stricta, a perennial relative of Arabidopsis. Evolution 2011, 65:771–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.••.Fishman L, Sweigart AL, Kenney AM, Campbell S: Major quantitative trait loci control divergence in critical photoperiod for flowering between selfing and outcrossing species of monkeyflower (Mimulus). New Phytol 2014, 201:1498–1507 10.1111/nph.12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper illustrates that two major-effect QTL for critical photoperiod explain nearly all variation in flowering time between allopatric and sympatric pairs of sister taxa Mimulus guttatus and M. nasutus, which likely contribute to prezygotic reproductive isolation nature.

- 16.Kiang YT, Hamrick JL: Reproductive isolation in the Mimulus guttatus–M. nasutus complex. Am Midland Nat 1978, 100:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CA, Lowry DB, Nutter LI, Willis JH: Natural variation for drought-response traits in the Mimulus guttatus species complex. Oecologia 2010, 162:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivey CT, Carr DE: Tests for the joint evolution of mating system and drought escape in Mimulus (vol 109, pg 583, 2012). Ann Bot 2012, 109:1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall MC, Basten CJ, Willis JH: Pleiotropic quantitative trait loci contribute to population divergence in traits associated with life-history variation in Mimulus guttatus. Genetics 2006, 172:1829–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendez-Vigo B, Martinez-Zapater JM, Alonso-Blanco C: The flowering repressor SVP underlies a novel Arabidopsis thaliana QTL interacting with the genetic background. PLoS Genet 2013, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry DB, Modliszewski JL, Wright KM, Wu CA, Willis JH: The strength and genetic basis of reproductive isolating barriers in flowering plants. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2008, 363:3009–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stebbins G: Flowering Plants: Evolution Above the Species Level. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 1974, . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett SCH, Ness RW, Vallejo-Marin M: Evolutionary pathways to self-fertilization in a tristylous plant species. New Phytol 2009, 183:546–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwillie C, Kalisz S, Eckert CG: The evolutionary enigma of mixed mating systems in plants: occurrence, theoretical explanations, and empirical evidence. Ann Rev Ecol Evol Syst 2005, 36:47–79. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ornduff R: Reproductive biology in relation to systematics. Taxon 1969:121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwillie C, Sargent RD, Eckert CG, Elle E, Geber MA, Johnston MO, Kalisz S, Moeller DA, Ree RH, Vallejo-Marin M et al. : Correlated evolution of mating system and floral display traits in flowering plants and its implications for the distribution of mating system variation. New Phytol 2010, 185:311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fishman L, Kelly AJ, Willis JH: Minor quantitative trait loci underlie floral traits associated with mating system divergence in Mimulus. Evolution 2002, 56:2138–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwillie C, Ritland C, Ritland K: The genetic basis of floral traits associated with mating system evolution in Leptosiphon (Polemoniaceae): an analysis of quantitative trait loci. Evolution 2006, 60:491–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grillo MA, Li CB, Fowlkes AM, Briggeman TM, Zhou AL, Schemske DW, Sang T: Genetic architecture for the adaptive origin of annual wild rice, Oryza nivara. Evolution 2009, 63:870–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sicard A, Stacey N, Hermann K, Dessoly J, Neuffer B, Baurle I, Lenhard M: Genetics, evolution, and adaptive significance of the selfing syndrome in the genus Capsella. Plant Cell 2011, 23:3156–3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.••.Slotte T, Hazzouri KM, Stern D, Andolfatto P, Wright SI: Genetic architecture and adaptive significance of the selfing syndrome in Capsella. Evolution 2012, 66:1360–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors of this paper find that relatively few loci of large effect underlie floral traits associated with mating system divergence between Capsella rubella and C. grandiflora, in contrast to previous studies that found a highly polygenic basis of selfing. In addition, population genetic variation in genes near identified QTL support a history of directional selection driving floral divergence.

- 32.Foxe JP, Slotte T, Stahl EA, Neuffer B, Hurka H, Wright SI: Recent speciation associated with the evolution of selfing in Capsella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106:5241–5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.••.Brandvain Y, Slotte T, Hazzouri KM, Wright SI, Coop G: Genomic identification of founding haplotypes reveals the history of the selfing species Capsella rubella. PLoS Genet 2013, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, the authors use a novel haplotype approach to elucidate the evolutionary history of the highly selfing species Capsella rubella. They infer that C. rubella likely originated from multiple founding individuals and did not experience an initial bottleneck, but that subsequent genetic drift and linked selection have drastically reduced the effective population size since C. rubella’s evolution ~50–100 kya.

- 34.Guo YL, Bechsgaard JS, Slotte T, Neuffer B, Lascoux M, Weigel D, Schierup MH: Recent speciation of Capsella rubella from Capsella grandiflora, associated with loss of self-incompatibility and an extreme bottleneck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106:5246–5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo YL, Zhao X, Lanz C, Weigel D: Evolution of the S-locus region in Arabidopsis relatives. Plant Physiol 2011, 157:937–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roels SAB, Kelly JK: Rapid evolution caused by pollinator loss in Mimulus guttatus. Evolution 2011, 65:2541–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.••.Slotte T, Hazzouri KM, Agren JA, Koenig D, Maumus F, Guo YL, Steige K, Platts AE, Escobar JS, Newman LK et al. : The Capsella rubella genome and the genomic consequences of rapid mating system evolution. Nat Genet 2013, 45:831–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In addition to publishing the Capsella rubella reference genome, this paper finds evidence for parallel changes in gene expression associated with the evolution of selfing in Capsella and Arabidopsis. The authors also detect an accumulation of non-synonymous variation in C. rubella relative to its outcrossing sister species, C. grandiflora, consistent with a reduced efficacy of purifying selection.

- 38.Pollak E: On the theory of partially inbreeding finite populations. 1. Partial selfing. Genetics 1987, 117:353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fishman L, Willis JH: Pollen limitation and natural selection on floral characters in the yellow monkeyflower, Mimulus guttatus. New Phytol 2008, 177:802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossenbacher DL, Whittall JB: Increased floral divergence in sympatric monkeyflowers. Evolution 2011, 65:2712–2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg EE, Igic B: Tempo and mode in plant breeding system evolution. Evolution 2012, 66:3701–3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright SI, Kalisz S, Slotte T: Evolutionary consequences of self-fertilization in plants. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2013, 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettengill JB, Moeller DA: Tempo and mode of mating system evolution between incipient Clarkia species. Evolution 2012, 66:1210–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.•.Hazzouri KM, Escobar JS, Ness RW, Killian Newman L, Randle AM, Kalisz S, Wright SI: Comparative population genomics in Collinsia sister species reveals evidence for reduced effective population size, relaxed selection, and evolution of biased gene conversion with an ongoing mating system shift. Evolution 2013, 67:1263–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper found that highly selfing Collinsia rattanii has less than half the level of nucleotide variation than its outcrossing sister species C. linearis, and has accumulated more deleterious alleles, consistent with a reduced efficacy of purifying selection. Comparisons of gene expression and function suggest a role for changes in expression underlying floral divergence.

- 45.Busch JW, Joly S, Schoen DJ: Demographic signatures accompanying the evolution of selfing in Leavenworthia alabamica. Mol Biol Evol 2011, 28:1717–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glemin S, Bazin E, Charlesworth D: Impact of mating systems on patterns of sequence polymorphism in flowering plants. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2006, 273:3011–3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ness RW, Siol M, Barrett SCH: Genomic consequences of transitions from cross- to self-fertilization on the efficacy of selection in three independently derived selfing plants. BMC Genomics 2012, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B: Quantitative genetics in plants – the effect of the breeding system on genetic-variability. Evolution 1995, 49:911–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartkowska MP, Johnston MO: Quantitative genetic variation in populations of Amsinckia spectabilis that differ in rate of self-fertilization. Evolution 2009, 63:1103–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stebbins GL: Self fertilization and population variability in the higher plants. Am Nat 1957, 91:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wright SI, Ness RW, Foxe JP, Barrett SCH: Genomic consequences of outcrossing and selfing in plants. Int J Plant Sci 2008, 169:105–118. [Google Scholar]