Abstract

d-myo-Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are Ca2+ channels activated by the intracellular messenger inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3, 1). The glyconucleotide adenophostin A (AdA, 2) is a potent agonist of IP3Rs. A recent synthesis of d-chiro-inositol adenophostin (InsAdA, 5) employed suitably protected chiral building blocks and replaced the d-glucose core by d-chiro-inositol. An alternative approach to fully chiral material is now reported using intrinsic sugar chirality to avoid early isomer resolution, involving the coupling of a protected and activated racemic myo-inositol derivative to a d-ribose derivative. Diastereoisomer separation was achieved after trans-isopropylidene group removal and the absolute ribose–inositol conjugate stereochemistry assigned with reference to the earlier synthesis. Optimization of stannylene-mediated regiospecific benzylation was explored using the model 1,2-O-isopropylidene-3,6-di-O-benzyl-myo-inositol and conditions successfully transferred to one conjugate diastereoisomer with 3:1 selectivity. However, only roughly 1:1 regiospecificity was achieved on the required diastereoisomer. The conjugate regioisomers of benzyl derivatives 39 and 40 were successfully separated and 39 was transformed subsequently to InsAdA after amination, pan-phosphorylation, and deprotection. InsAdA from this synthetic route bound with greater affinity than AdA to IP3R1 and was more potent in releasing Ca2+ from intracellular stores through IP3Rs. It is the most potent full agonist of IP3R1 known and .equipotent with material from the fully chiral synthetic route.

Introduction

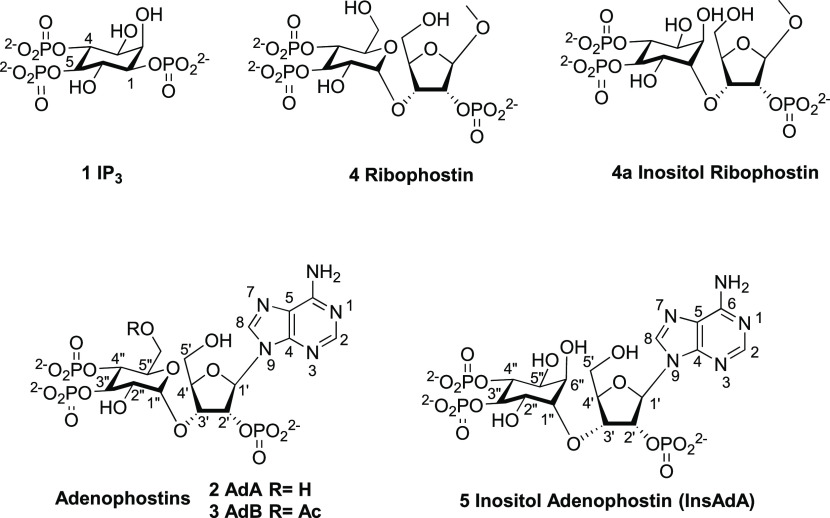

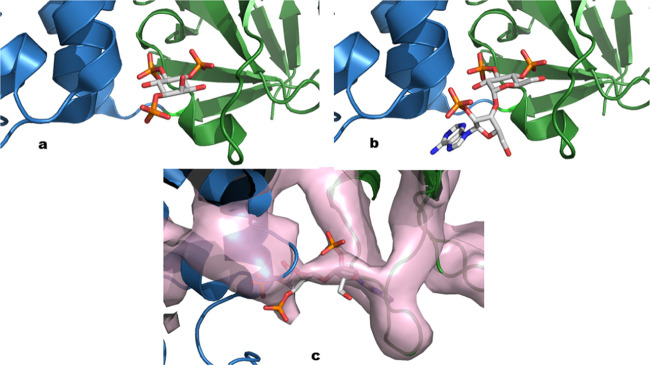

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are intracellular Ca2+ channels. In most animal cells, IP3Rs release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in response to the many extracellular stimuli that evoke formation of d-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3, 1, Figure 1). IP3Rs thereby generate Ca2+ signals that regulate diverse cellular processes.1 IP3R activation is initiated by IP3 binding to the IP3-binding core (IBC, residues 224–604) of each subunit of the tetrameric receptor.2 The two domains (α and β) of the IBC form a clam-shaped structure, lined by conserved residues that coordinate IP3 (Figure 2a).3 The 4-phosphate of IP3 interacts primarily with IBC-β, whereas the 1- and 5-phosphates interact predominantly with residues in IBC-α. Interaction of the critical vicinal 4- and 5-phosphates4,5 with opposing sides of the clam allows IP3 to partially close the clam.6−8 This initial conformational change then propagates through putative Ca2+-binding sites to the pore, where the movement of occluding hydrophobic residues within the pore opens a path for Ca2+ to leak from the ER lumen to the cytosol.1,8

Figure 1.

InsAdA (5) and other potent IP3R agonists.

Figure 2.

Binding of IP3 and AdA to the IBC. (a) Interaction of IP3 with the IBC based on the X-ray crystal structure of the IBC of IP3R1 in complex with IP3 (adapted from the Protein Data Bank, 1N4K). The α- and β-domains are shown in blue and green, respectively. (b) Model of AdA bound to the IBC of IP3R115 (adapted from the Protein Data Bank, 1N4K). (c) AdA bound to the IBC of IP3R1 and matching electron density map revealed by cryo-EM16 (adapted from the Protein Data Bank, 6MU1).

Although an extensive understanding of the structure–activity relationships (SARs) of IP3 analogues and other non-inositol-based derivatives has been established, there is still much ongoing interest in the structure-based design of new ligands of IP3Rs.9−12 Adenophostin A (AdA, 2) and its acetate analogue, adenophostin B (AdB, 3), are highly potent IP3R agonists isolated from Penicillium brevicompactum.13 Both compounds bind to IP3Rs with about tenfold greater affinity than IP3, and they stimulate Ca2+ release with about tenfold higher potency than IP3.1414 These compounds and their analogues have elicited much synthetic and biological interest.1,4,5

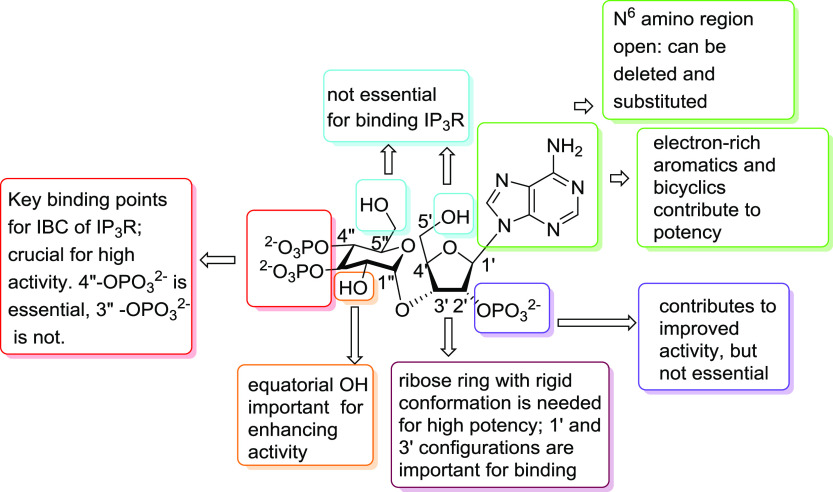

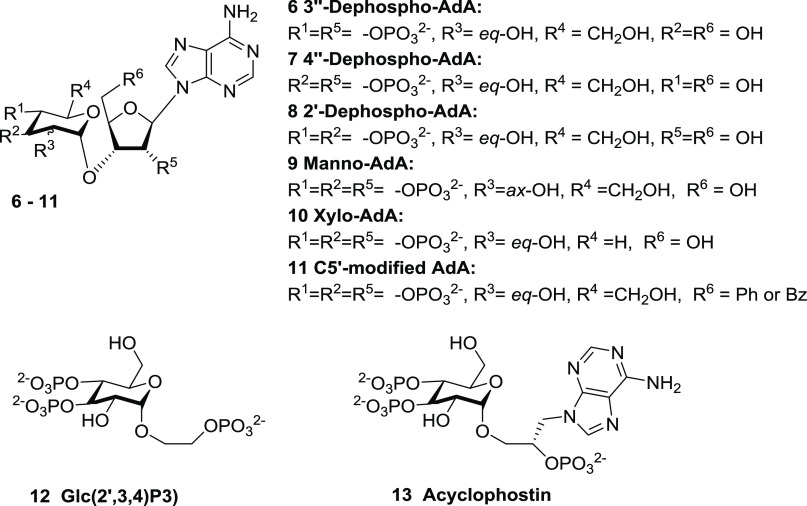

The vicinal 3″,4″-bisphosphate motif in AdA resembles the critical 4,5-bisphosphate moiety in IP3. SAR considerations show that the 3″,4″-bisphosphates in AdA (Figure 5, red area), although not essential for Ca2+ release,5 are important since 3″-dephospho-AdA (Figure 3, compound 6) is almost 10 000-fold less potent than AdA, and 4″-dephospho-AdA (Figure 3, compound 7) is inactive.5,18 Loss of the 6-OH group from IP3 causes a ca. 100-fold decrease in potency.4 The 2″-hydroxyl of AdA may partially mimic the 6-OH of IP3 since manno-AdA (Figure 3, compound 9), in which the C2″ configuration is inverted, is 5–10-fold less potent than AdA.10,14 The enhanced potency of AdA was proposed to be due to its adenosine moiety, causing a better positioning of the 2′-phosphate relative to the 1-phosphate of IP3, but this was not confirmed17 (vide infra). The 80-fold loss of potency after removing the 2′-phosphate from AdA to give 8 (Figure 3) is less than the 200-fold loss of potency associated with loss of the 1-phosphate from IP3.1818 An attempt to move the 1-phosphate of IP3 further from the ring did not enhance activity.19

Figure 5.

Structural determinants of AdA activity.

Figure 3.

Structure of AdA analogues with varied phosphates or hydroxyls.

Removing the CH2OH group from the C5″-position of the glucose unit has a minimal effect as indicated for xylo-AdA (Figure 3, compound 10), which is approximately twofold less potent than AdA.20 The C5′ hydroxyl is also unimportant, as indicated by analogues with aromatic groups conjugated at the C5′-position (Figure 3, compound 11), both of which are equipotent with AdA.21 This allowed attachment of a large fluorescent moiety, providing both a potent fluorescent analogue of AdA and a means of measuring low concentrations of IP3.2222

An intact ribose ring is important for maintaining AdA in a conformation for binding to the IBC. Early efforts to simplify the structure of AdA led to glucopyranoside 2′,3,4-trisphosphate (Figure 3, compound 12),23,24 a full agonist with tenfold lesser potency than IP3, indicating the likely importance of the more constrained ribose moiety to keep its phosphate group in the correct position. Acyclophostin (Figure 3, compound 13) was also designed to provide an analogue with an opened ribose ring,25 with the adenine base attached to the anomeric position of glucose via a flexible three-carbon chain. Acyclophostin has a slightly higher affinity than IP3, but its Ca2+-mobilizing activity is pH-dependent.25 Most recently, polyphosphorylated analogues derived from both d- and l-glucose were synthesized, some of which can be viewed as truncated analogues of AdA that refine SAR understanding.26

Removal of the adenine moiety or an electron-rich aromatic ring from the C1′-position of AdA leads to analogues (Figure 4, compounds 4, 14, 15) with reduced potency.10,17 Furanophostin (15) and ribophostin (4), in which the adenine is replaced with a H or methoxyl group, respectively, have similar potency to IP3, revealing the minimal substitution at C1′ to achieve potent receptor activation.27,28 Introduction of an imidazole ring at C1′ led to imidophostin (14), equipotent with IP3.2929 Further expansion into a simple purine base gave purinophostin 16 (Figure 4, X = H), nearly as potent as AdA, showing that the N6-position may be removed.29 A bulky group is also tolerated at the N6-position, consistent with the purine moiety being in a rather open area of the IBC.15 Similarly, guanophostin (Figure 4, compound 17) is also equipotent with AdA.30 However, when the adenine is replaced with an indole, compounds (Figure 4, compound 18) show reduced binding affinity; interestingly, however, the 4-fluoroindole derivative (Figure 4, compound 18, X = F) is IP3R1-selective.31

Figure 4.

Structures of AdA analogues with modified substituents at the C1′-position.

More recently, a triazole ring replacement for adenine led to triazolophostins (Figure 4, compound 19), potent agonists of IP3R.32 Triazolophostin (19, X = H) is almost as potent as AdA in releasing Ca2+ through IP3R1. While the imidazole analogue (Figure 4, compound 14) is only slightly more potent than IP3, the triazole equivalent (19, X = H) is 13 times better, suggesting subtle effects on the binding. Dimer analogues (Figure 4, compound 20) are broadly equipotent to AdA.33

SAR and modeling studies suggest the potential for enhanced binding of the adenine ring with Arg504 in the IBC through a cation−π interaction (Figure 2b).15,34 Studies with a mutated IP3R1 with Arg504 replaced by glutamine revealed reduced activity for both IP3 and AdA; however, the detrimental effect is more marked for AdA than for IP3 (353-fold vs 13-fold17). This concurs with the observation that Arg504 plays a far more important role in AdA binding, potentially via the cation−π interaction.17,18 Recent analysis using single-particle cryo-EM, however, suggested a different binding mode for AdA (Figure 2c), one in which the adenine ring interacts with residues from R265 to S277 of β-TF2.16 Further investigations are needed to validate this binding mode, however, as the ligand of the model presents incorrect configurations on both glucose and ribose rings and clashes between the adenine and residues in β-TF2 were observed (PDB 6MU1). Thus, the exact binding mode of AdA at IP3R is controversial, but our best working model is still that shown in Figure 2b.

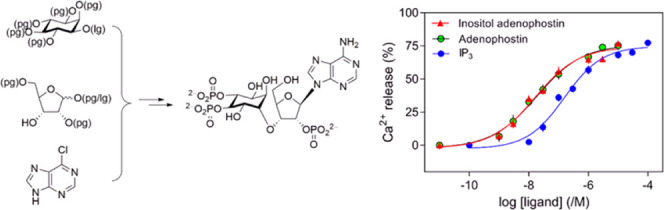

Despite this extensive SAR insight, most studies have addressed iterative variations in the base, ribose, phosphate, and glucose moieties that are synthetically accessible (Figure 5). While it has long been hypothesized that in AdA the glucopyranoside moiety directly mimics inositol, direct replacement with an inositol surrogate has remained unexplored until recently when we synthesized the novel InsAdA (Figure 1) through conjugation of a protected and activated chiral myo-inositol derivative with a protected chiral ribose unit, followed by further elaboration, phosphorylation, and deblocking.35 InsAdA, with a d-chiro-inositol substituting for an α-d-glucose moiety, was interestingly slightly more potent than AdA itself. Importantly, the extra 6″-axial hydroxyl group replacing the AdA pyranoside ring oxygen and the overall conserved high activity offer new potential for wider synthetic elaboration than just AdA itself. Moreover, although missing the adenine base, the corresponding d-chiro-inositol ribophostin counterpart (Figure 1, compound 4a) is the most potent small-molecule IP3 receptor agonist without a nucleobase yet synthesized, with potency and binding affinity for IP3R approaching those of AdA.36

We now report an alternative synthetic strategy employing intrinsic d-ribose chirality and involving the separation of the diastereoisomers of a suitably protected chiro-inositol-ribonucleoside conjugate derived from a racemic myo-inositol building block. Optimal conditions for regio-monobenzylation on the inositol ring of protected conjugates and for the removal of different protecting groups were also explored. InsAdA was evaluated biologically, both for its IP3R1 affinity in equilibrium competition binding assays and its ability to release Ca2+ from intracellular stores of permeabilized cells, and was directly compared with material from the earlier synthetic route.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

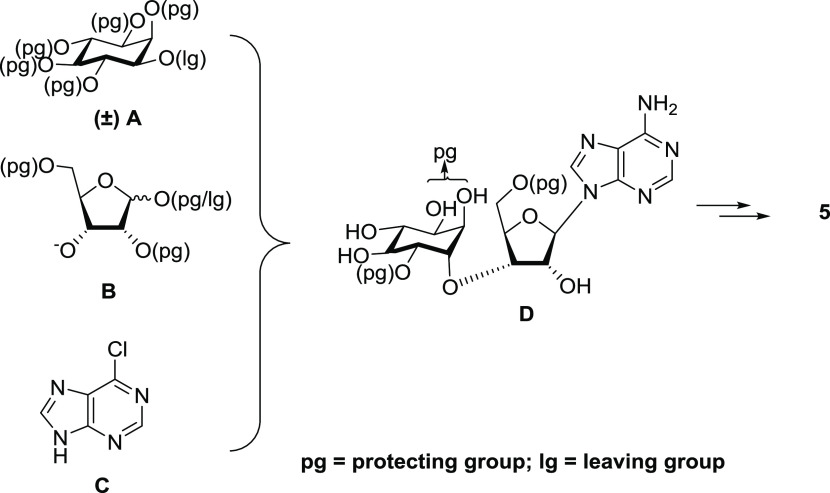

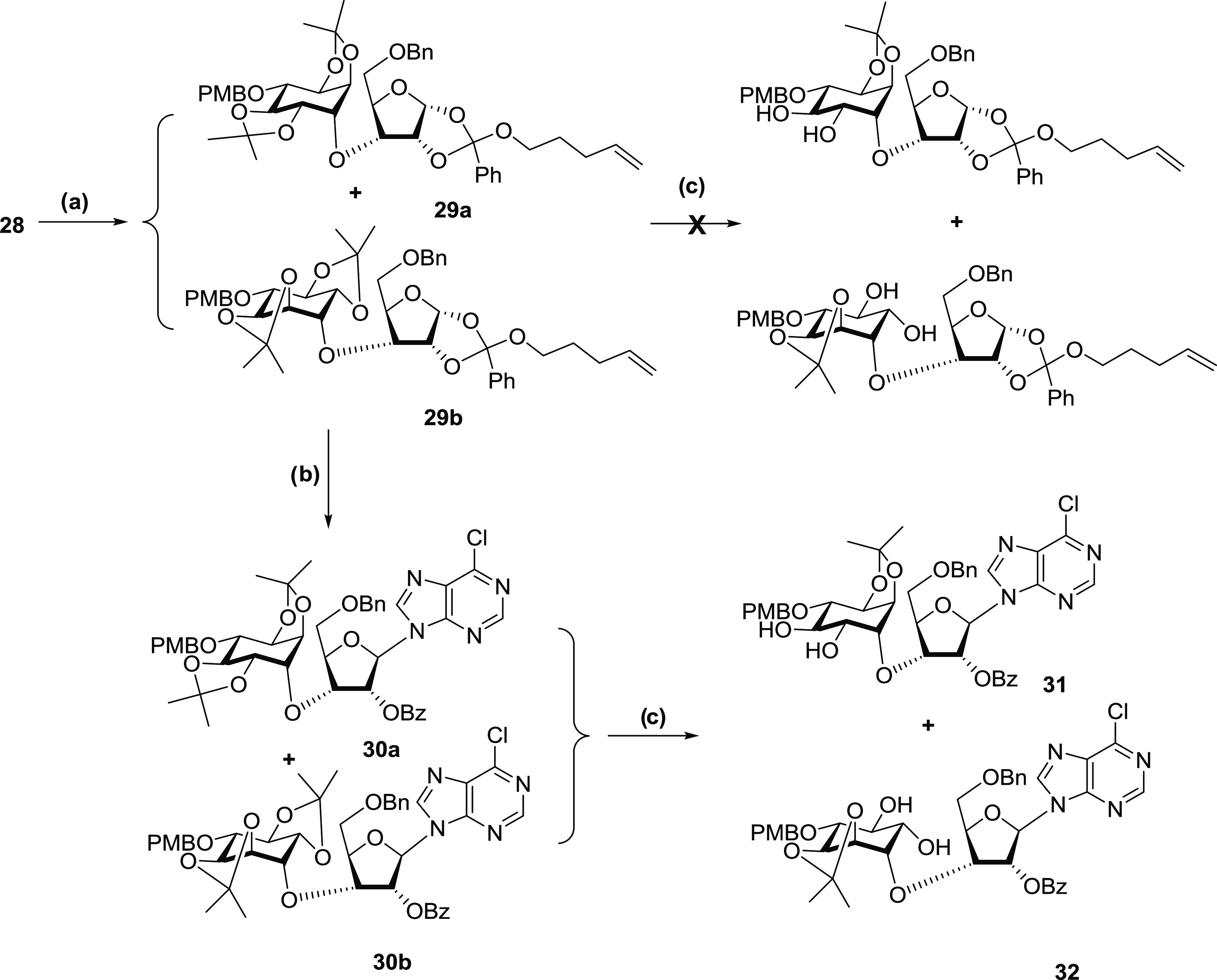

Our synthetic route for InsAdA involved coupling a suitably protected and activated racemic myo-inositol derivative (Figure 6A) to a protected d-ribose derivative (Figure 6B) using a Williamson ether synthetic approach, followed by the introduction of a purine base (Figure 6C) and subsequent separation of the diastereoisomers of the resulting fully protected conjugates. Configurational inversion upon coupling led to the conversion of the myo-inositol motif into a chiro-inositol component. Thus, the nucleoside conjugates possess both d- and l-chiro-inositol. The assignment of the absolute configuration of diastereoisomers was achieved by comparison of NMR data for material synthesized through the route using chiral precursors.35 Conditions for regioselective protection of specific hydroxyl groups on the inositol ring were explored using a stannylene-mediated reaction. The fully protected conjugated isomers with benzyl protection at adjacent positions of the d-chiro-inositol ring were separated successfully and transformed subsequently to InsAdA after amination, removal of para-methoxybenzyl (PMB) protection, pan-phosphorylation, and deprotection. Note, as earlier,35 that no N6 amino protection of the adenine moiety before the phosphorylation was planned for the synthetic route.

Figure 6.

Convergent synthetic strategy for InsAdA (5) synthesis. (A) Protected (±)-myo-inositol moiety, (B) protected d-ribose moiety, (C) 6-chloropurine, and (D) protected InsAdA precusor.

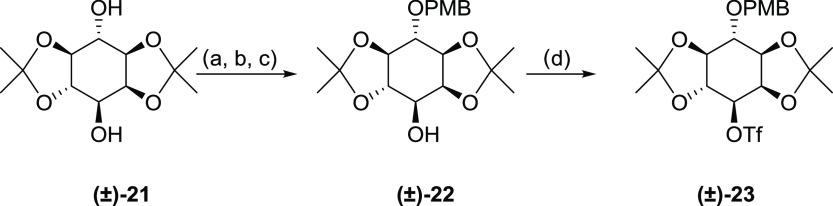

The six secondary hydroxyl groups of myo-inositol possess similar reactivity.37 However, the reactivity of free cyclitol hydroxyls differs depending on several factors including ring conformation, hydrogen-bonding interactions with neighboring groups, and the conditions used for protection.4,38 A commonly used strategy is acid-mediated ketalization of vicinal-diol groups.37,39 Diketal (±)-1,2:4,5-di-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (Scheme 1, 21) can be synthesized from myo-inositol by a simple two-step process.40,41 The 1,2:4,5-diketal structure forces the ring into a rigid conformation, facilitating selective individual protection of the other two free hydroxyls as a 6-O-PMB derivative and 3-O-triflate for activation. This conformational rigidity stabilizes the triflate from undergoing β-elimination under alkaline conditions.35 Less rigid combinations failed in the subsequent coupling step.35

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Racemic myo-Inositol Building Block (±)-(23).

Reagents and conditions: (a) tosyl imidazole (1.01 equiv), CsF (1.2 equiv), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), room temperature (rt), 18 h; (b) PMBCl (1.1 equiv), NaH (1.2 equiv), DMF, rt, 16 h; (c) Mg (20 equiv), dichloromethane (DCM)/MeOH 1/1, reflux, 30 min, then rt, 3 h; and (d) Tf2O (1.2 equiv), pyridine, DCM, 0–25 °C.

To tether the protected myo-inositol moiety (Figure 6A) to the ribose moiety (Figure 6B) in a second-order nucleophilic substitution (SN2) fashion, a triflate leaving group needs to be introduced at the 3-position of 21. The C3–OH position of 21 was initially protected via a substantially selective tosylation using 1-(p-toluenesulfonyl)imidazole in the presence of CsF. The 3-mono-tosyl product and 3,6-di-tosyl byproduct were obtained in a respective 6:1 ratio, and the mixture subsequently subjected to para-methoxybenzylation, followed by detosylation using magnesium in methanol and dichloromethane42 to give (±)-22. In the process, the 3,6-di-tosyl byproduct was converted back to (±)-21 that can be easily removed. All reactions could be achieved in an efficient one-pot process, and we found that combining these three steps without separating byproducts greatly improves efficiency. The reaction of (±)-22 with triflic anhydride in the presence of pyridine in DCM generated the desired activated precursor (±)-23 (Scheme 1).

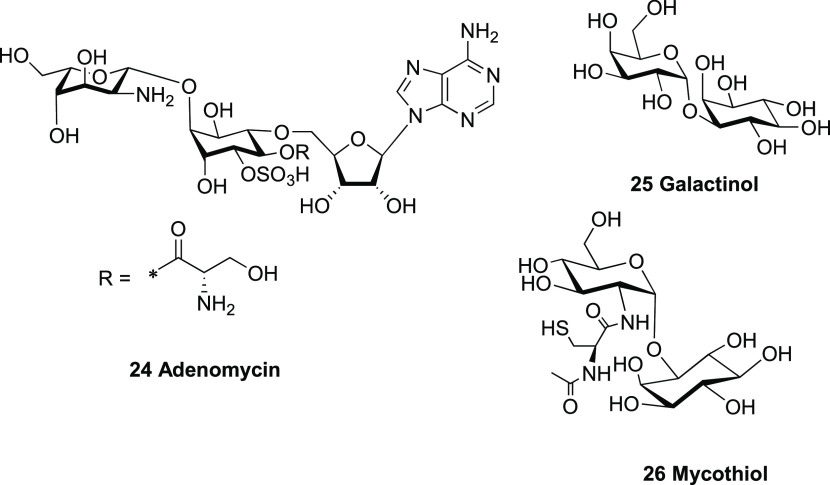

The synthesis of the diastereoisomeric conjugate between the protected dl-myo-inositol and d-ribose building blocks involved a secondary–secondary SN2 ether formation between the 3-oxyanion of the ribose derivative and the 3′-O-triflate group of the myo-inositol unit. The structural feature of a chiro-inositol–ribose conjugate is found in the nucleoside antibiotic molecule adenomycin (24), produced by Streptomyces griseoflavu(43,44) (Figure 7). However, in this case, the inositol is attached to the primary alcohol of the ribose. Other sugar–inositol conjugates found in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells include small molecules such as galactinol (25),45 mycothiol (26)46 and more complex molecules such as glycosylphosphatidylinositols (GPIs),47−49 acting as anchors for cell-surface proteins. As the inositol moiety is tethered to the anomeric position of the sugar molecule, these compounds can usually be prepared via a straightforward O-glycosylation reaction onto the sugar donor.50−52 The structural feature of an inositol–sugar conjugate with a highly functionalized sec–sec ether linkage as seen in InsAdA is, however, rarely reported in the literature and therefore a unique synthetic route was needed.

Figure 7.

Representative natural compounds containing the sugar–cyclitol moiety.

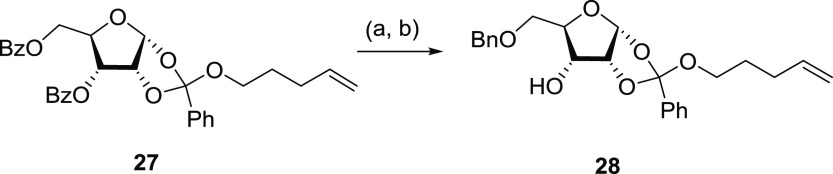

The d-ribose moiety (Figure 6B) needs not only to be fully protected on all hydroxyl groups except the 3-OH, but also to behave like an N-glycosylation donor for the nucleoside synthesis. Numerous methodologies have been developed to prepare a nucleoside via an N-glycosylation reaction.53 Among them, commonly used strategies include (a) using protected sugar halide as a donor to react with a metal salt of the nucleobase,54,55 (b) using per-acylated sugars as a donor to react with the base under fusion conditions,56 and (c) the silyl-Hilbert–Johnson method, modified by Vorbrüggen, that has now become the preferred methodology.57,58 This latter procedure involves a silylated heterocycle reacting with protected sugar acetate in the presence of a Lewis acid such as SnCl4 or trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf). To further improve selectivity and yield, more efficient methodologies were devised.59 Fraser-Reid developed a versatile n-pentenyl orthoester donor system, initially used in the synthesis of an oligosaccharide.60,61 This was later adapted into a reverse synthetic strategy for preparing ribonucleosides, which allows different structural modifications on the ribose moiety before the N-glycosylation occurs in very mild conditions.62 3′,5′-Dibenzoyl-d-ribofuranose-1′,2′-n-pentenyl orthoester (27) was prepared62 and after removing benzoyl groups, the primary alcohol was selectively protected with a benzyl group using silver carbonate63 in more than 90% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the d-Ribose Building Block (28).

Reagents and conditions: (a) CH3ONa and MeOH and (b) BnBr, Ag2CO3, and toluene.

The sec–sec ether formation between 28 and racemic 23 was achieved by reacting the C3′-alkoxide of 28 with triflate (±)-23 under very mild conditions. The C3 SN2 substitution of the myo-inositol moiety generated the desired conjugate of dl-chiro-inositol and d-ribose (29a, 29b) as a pair of diastereoisomers in a 1:1 ratio in 79% yield (Scheme 3). Initial attempts to separate the diastereoisomers before N-glycosylation were unsuccessful, as the removal of the 2,3-trans-O-isopropylidene resulted in ring opening of the orthoester group (Scheme 3). The reaction of 29a and 29b with p-toluenesulfonic acid (pTSA) and ethylene glycol in DCM only generated a mixture of polar byproducts. Therefore, the required 6-chloropurine base element was introduced at this stage through an N-glycosylation reaction promoted by iodonium ion generated in situ from N-iodosuccinimide.62,64 Reacting the silylated 6-chloropurine with 29a and 29b in the presence of N-iodosuccinimide, ytterbium triflate, and 3 Å molecular sieve in acetonitrile at room temperature produced compounds 30a and 30b in good yields (Scheme 3). We found that adding molecular sieve powder to the system significantly improved the yield. The diastereoisomers of 30a and 30b could not be separated with silica-based chromatography in varied solvent systems. However, selective removal of the 2″,3″-trans-O-isopropylidene group generated the diols 31 and 32 that could be differentiated slightly by silica-based thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The separation of 31 and 32 was difficult using chromatography on a silica column. The optimal separation was eventually achieved by a gradient solvent system of acetone and DCM on a silica column with a loading ratio of 1:133 (w/w, sample/silica). The identification of the less polar isomer 31 as possessing the d-chiro-inositol motif was performed by comparing the NMR data with those of the same compound obtained through a synthetic route with completely chiral precursors.35

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the d- and l-chiro-Inositol Nucleoside Derivatives (31, 32).

Reagents and conditions: (a) (±)-23, NaH, hexamethylphosphoric triamide (HMPA), tetrahydrofuran (THF), rt, 12 h; (b) Yb(OTf)3, NIS, silylated 6-chloropurine, CH3CN, rt, 24 h; (c) pTSA, ethylene glycol, DCM, rt, 30 min; and column separation.

The selective benzylation of the inositol C2″–OH in the presence of C3″–OH needs to be conducted under mild conditions, as the purine base cannot tolerate alkylating reagents under basic conditions.65 This was illustrated by our failed attempts to benzylate the hydroxyl groups directly in the presence of NaH, DMF/THF, and BnBr. With both C2″ and the C3″ hydroxyls being equatorial, they are positioned in a very similar environment in terms of stereochemistry and hydrogen-bonding capacity.66 Several conditions for the regioselective alkylation of sugar molecules have been reported using an organic metal reagent as an activator, including an organotin,67 nickel complex,68 silver salt,63 and, more recently, an iron complex.69 Organotin compounds such as dibutyltin oxide and tributyltin oxide are still widely used for selective manipulation of carbohydrate molecules,70,71 despite their potential toxicity. Regioselective alkylations were achieved through the preactivation of the two adjacent hydroxyl groups by forming a cyclic dioxolane-like intermediate with the organotin reagent. It was noted, however, that tin-mediated benzylation reactions on trans-diols are less selective as those on cis-diols.72

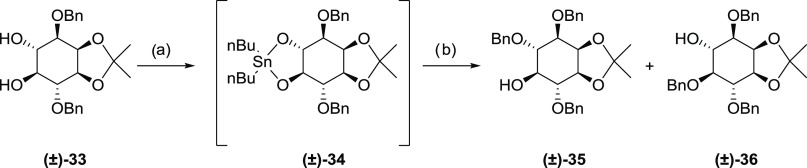

To establish suitable conditions for the monobenzylation on the desired 31, we used the myo-inositol derivative racemic 33 as a model for optimizing the tin-mediated reaction (Scheme 4). Benzylation of 33 had been previously performed under either strongly basic conditions73 or via tin-mediated one-pot reaction conditions.74 We used a two-phase reaction condition, i.e., isolation of the stannylene-ketal intermediate 34 before adding BnBr, to avoid possible benzylation on the purine moiety. Initially, the reaction was performed in a mixed solvent of toluene and methanol for both phases (Table 1, entry 1). However, no product was observed when the second phase was conducted at room temperature after 3 days. Even though products 35 and 36 could be obtained in 40% and 20% yields, respectively, after refluxing the reaction mixture for 32 h, this condition is not suitable for the target molecule 31 due to potential interference with the purine ring. We changed the solvent for the second phase to DMF and used CsF (Table 1, entry 2) or CsF/TBAI (Table 1, entry 3) as catalysts. Compound 35 was obtained in 20% and 27% yields; however, the other regioisomer 36 was also produced in 16–20% yield, indicating low selectivity. Increasing both dibutyltin oxide and BnBr to 2 equiv and changing the solvent for the first phase to acetonitrile improved the selectivity slightly to 2:1 (Table 1, entry 4). The reaction was then conducted with 3 Å molecular sieves added to the system on the second phase and, with benzyl bromide increased to 3 equiv, compound 35 was obtained in 57% yield with a preference ratio of 3.5:1 (Table 1, entry 5).

Scheme 4. Optimization of the Monobenzylation of trans-Diol (33).

Reagents and conditions: (a) Bu2SnO, CH3CN, and reflux and (b) BnBr, CsF, TBAI, 3 Å molecular sieves, DMF, and rt.

Table 1. Conditions for the Monobenzylation of (±)-33.

| entry | Bu2SnO (equiv) | BnBr (equiv) | conditions | yield 35 (%) | yield 36 (%) | 33 (%) recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | mixed solvent of CH3OH and tolulene, refluxing, phase two, TBAI, refluxing | 40 | 20 | 25 |

| 2 | 1.1 | 1.5 | phase one solvent: toluene, refluxing; phase two solvent: DMF, CsF, –10 °C | 20 | 16 | 23 |

| 3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | phase one solvent: toluene, refluxing; phase two solvent: DMF, CsF, TBAI, rt | 27 | 20 | 10 |

| 4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | phase one solvent: CH3CN, refluxing; phase two solvent: DMF, CsF, TBAI, rt | 35 | 18 | 25 |

| 5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | phase one solvent: CH3CN, refluxing; phase two solvent: DMF, CsF, TBAI, 3 Å molecular sieves, rt | 57 | 16 | 17 |

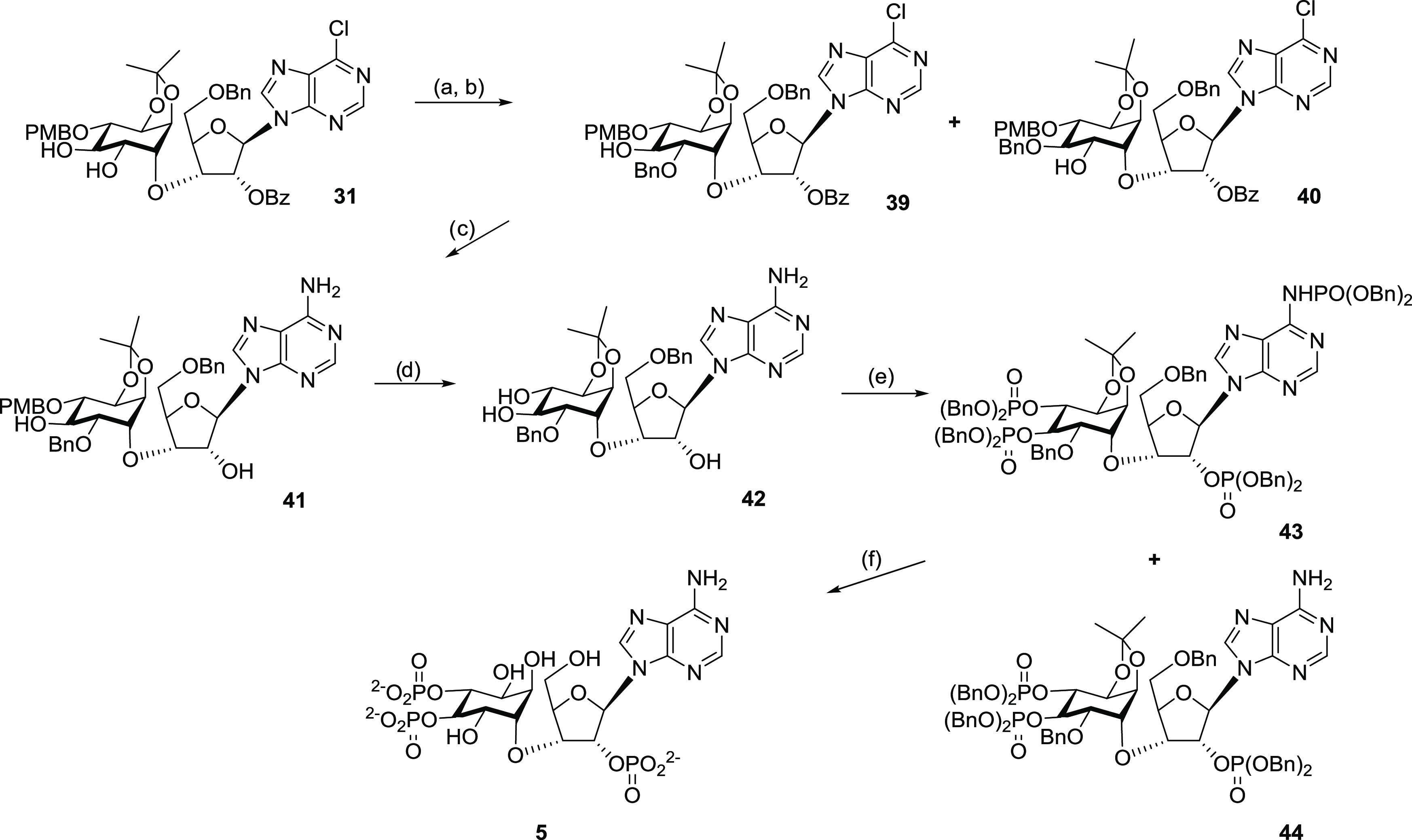

The benzylation conditions from Table 1, entry 5 were translated to the “undesired” diastereoisomer (32) containing the l-chiro-inositol motif as a model (Scheme 5). The monobenzylated products 37 and 38 were obtained in 58% yield. 1H NMR spectroscopy indicated that the two regioisomers were present in a 3:1 ratio. These two compounds were inseparable by a silica-based chromatography system. The same benzylation condition was then used on the “desired” d-chiro-inositol derivative 31. However, the benzylation was unfortunately much slower and less selective. Compounds 39 and 40 were obtained in 26% and 31% yields, respectively, with 27% of the starting material 31 recovered (Scheme 6). It was hypothesized that the behavioral difference toward the benzylation process between the two diastereoisomers 31 and 32 was due to stereo effects positioning the two adjacent hydroxyl groups in 31 in a hindered location. An AMMP force field minimization and conformational search were conducted for 31 with the VEGA ZZ program (version 3.1.1).75 With torsions set for C–O–C linker between the ribose and inositol parts and O-benzoyl group on the ribose ring, the lowest energy conformers with ribose in both 2′-C-endo and 3′-C-endo conformations indicated that the two hydroxyl groups were positioned between the inositol ring and the benzoyl ring, whereas for the “undesired” diastereoisomer 32, the two adjacent hydroxyl groups were positioned in a more exposed area.

Scheme 5. Monobenzylation of the Conjugate Containing the l-chiro-Inositol Motif (32).

Reagents and conditions: (a) Bu2SnO, CH3CN, and reflux and (b) BnBr, CsF, TBAI, 3 Å molecular sieves, DMF, and rt.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of InsAdA (5).

Reagents and conditions: (a) Bu2SnO, CH3CN, reflux, 18 h; (b) BnBr, CsF, TBAI, 3 Å molecular sieves, DMF, rt, 16 h; (c) NH3, C2H5OH, 78 °C, 20 h; (d) 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), DCM, rt, 4 min; (e) (BnO)2PN(i-Pr)2, imidazolium triflate, DCM/CD2Cl2, rt, 1 h, then tert-BuOOH (70%), −78 °C to rt in 30 min; and (f) 20% Pd(OH)2/C, cyclohexene, MeOH/H2O, reflux, 18 h.

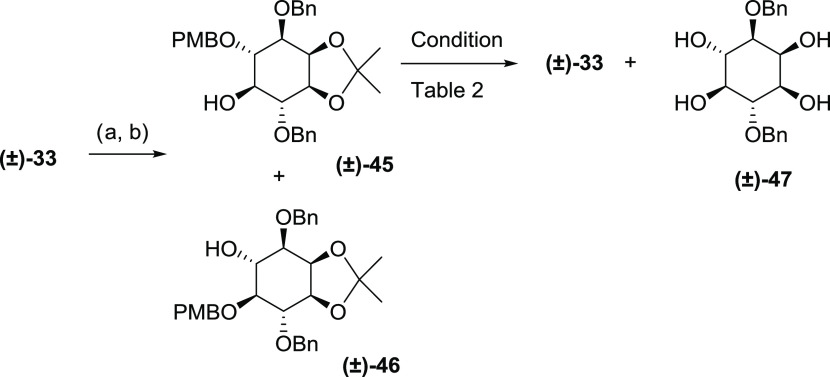

Removal of the para-methoxybenzyl (PMB) group can be achieved by an oxidative process using 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyanobenzoquinone (DDQ)76 or ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN).77 The conditions of 10% TFA in DCM have been successfully employed to remove PMB groups from sugar molecules without affecting the glycosidic linkage.78 Because of the presence of the sensitive 2,3-O-isopropylidene group, we initially avoided acidic conditions when deprotecting the model molecule 45(74) (Scheme 7). However, the oxidative process using CAN only generated the target compound 33 in low yield, along with the fully hydrolyzed byproduct 47 (Table 2, entry 1). The same reaction performed using a phosphate buffer system only improved the yield slightly (Table 2, entry 2). Using DDQ instead of CAN in the buffer system gave a significantly improved yield of 55% without the detection of byproduct 47 (Table 2, entry 3). However, the messy procedure of working up the DDQ reaction prompted us to try the TFA deprotection method78 on racemic 45. Surprisingly, the PMB ether of 45 was cleaved in as short a time as 3–4 min and gave an 80% yield of the product 33 (Table 2, entry 4). Longer reaction times even at lower temperatures generated more byproduct 47 (Table 2, entry 5). Therefore, using the same conditions in Table 2, entry 4, compound 41 was converted to the desired precursor 42 in 63% yield.

Scheme 7. PMB Removal Model Reaction.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Bu2SnO, CH3CN, and reflux and (b) PMBCl, CsF, TBAI, 3 Å molecular sieves, DMF, and rt.

Table 2. Conditions for PMB Removal from (±)-45.

| entry | conditions | (33) yield (%) | (47) yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CAN, CH3CN/H2O, rt. 45 min | 19 | 13 |

| 2 | CAN, CH3CN/H2O, Na2HPO4–NaH2PO4, buffer, pH 7.4, rt, 40 min, 0 °C | 25 | |

| 3 | DDQ, DCM/H2O, Na2HPO4–NaH2PO4, buffer, pH 7.4, rt, 1.5 h, 0 °C | 55 | |

| 4 | 10% TFA/DCM dried over 3 Å molecular sieves, rt, 3 min | 80 | |

| 5 | 10% TFA/DCM dried over 3 Å molecular sieves, 0 °C, 10 min | 55 | 25 |

The protected phosphate groups at the C2′-position of the ribose component and the 3″,4″-positions of the inositol component could be introduced via a phosphitylation reaction, followed by oxidation of the resulting P(III) intermediate to the corresponding P(V) triphosphate. Phosphoramidites are among the most widely used phosphitylation reagents with the advantage of being highly reactive, easily accessible, and, importantly, being able to react with hydroxyl groups under very mild conditions.79 Phosphoramidite reagents are usually activated by weak acids such as 1H-tetrazole;80 5-(p-nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole;81 4,5-dicyanoimidazol;82 benzimidazolium triflate;83 or imidazolium, anilinium, and pyridinium salts.84 Some activators such as pyridinium hydrochloride with aniline85 or imidazolium triflate86 could selectively promote O-phosphorylation over N-phosphorylation, therefore avoiding the necessity of protecting NH2 of nucleotide base.

Part of our strategy was not to protect the amino group of adenine. However, when 42 was reacted with 5.3 molar equiv of dibenzyl N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite, preactivated with imidazole triflate, and the product subsequently oxidized with tert-butyl hydroperoxide, no significant selectivity between OH groups and the adenine NH2 was observed; a mixture of tetrakisphosphate 43 and the desired trisphosphate 44 was obtained in a respective 4:3 ratio (Scheme 6). N6-phosphoramidate was distinguished easily from the other phosphotriesters by its 1H NMR resonance at 8.67 ppm for NH and a 31P NMR broad peak at 0.90 ppm. Nonselectivity was most likely due to an excess amount of phosphoramidite, which was used to ensure the complete hydroxyl phosphorylation.

N-Phosphoramidates can be hydrolyzed using strongly acidic,87−90 strongly basic, or metallic reagents.91 Hydrogenation of N-phosphate benzyl ester generated partially deprotected phosphoramidate that could be further converted to the fully deblocked free amino compound under controlled mild acidic conditions.92 Our final deprotection step was performed using a catalytic hydrogen transfer reaction with Pd(OH)2 as a catalyst and cyclohexene as a hydrogen source. After refluxing the mixed tris-O-phosphate-mono-N-phosphoramidate benzyl esters 43 in a mixture of methanol–water–cyclohexene over Pd(OH)2 on charcoal for 18 h, all protecting groups were removed, leading to the final target compound 5 in its free acid form. The concomitant removal of the N-phosphate and O-isopropylidene groups, attributed to the intrinsic acidity of the free phosphate groups, was observed in our earlier work.35 The strategy of removing four different types of protecting groups efficiently in a single step is particularly useful in solution-phase nucleotide synthesis to avoid cumbersome extra N-protection methods. Furthermore, the strategy is more suitable when the availability of only small amounts of material might preclude the easy use of phosphoramidite activators, e.g., imidazolium triflate for selective O- vs N-phosphitylation since this requires very careful titration of reagents and rigorous exclusion of water.93 Purification using semipreparative reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with 0.1 M tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB)–MeCN as an eluant gave the target InsAdA as its triethylammonium salt as a colorless glass after evaporation of buffer in vacuo.

In comparison with our earlier synthetic method using a chiral inositol building block as a precursor,35 the alternative approach reported here achieved the fully chiral target molecule using just the intrinsic protected d-ribose unit chirality to avoid resolution at an early stage, thus saving several steps. The present synthetic route should therefore offer a somewhat more economical and practical approach than that reported earlier,35 especially to the now anticipated further analogues of this highly potent ligand and those exploiting substitutions on the 6″-axial hydroxyl group that replaces the pyranoside ring oxygen of AdA. Equally, this broad synthetic approach may also be applicable to such analogues of d-chiro-inositol ribophostin (Figure 1, compound 4a),36 a related and simpler ligand that showed unexpectedly potent InsP3R activity in comparison to its disaccharide counterpart ribophostin and worthy of further development.

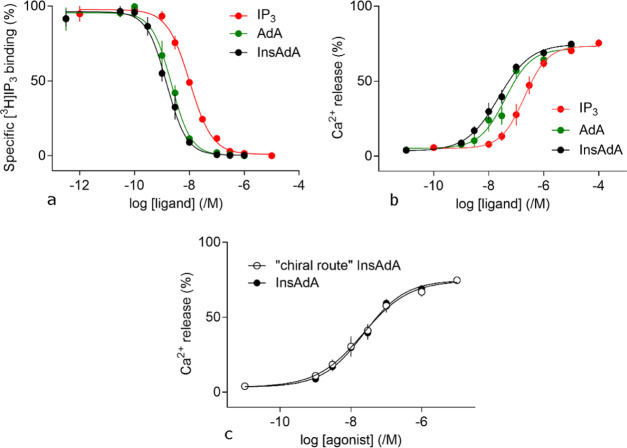

Biology

We assessed the ability of InsAdA to bind with IP3R and stimulate Ca2+ release. In equilibrium competition binding assays using [3H]–IP3, InsAdA bound to the full-length IP3R1 of cerebellar membranes with greater affinity than IP3, and its affinity was slightly, but not significantly, higher than that of AdA (Figure 8a and Table 3). The shared features of InsAdA and AdA provide likely explanations for the high affinity of InsAdA. The cyclitol ring of InsAdA most likely adopts a conformation that locates the critical 3″,4″-bisphosphates in the same area as that of the 3″,4″-bisphosphates of AdA, and the C2″–OH of inositol sits in the area occupied by the 2″-OH of AdA. The rigidity of the ribose unit plays a key role in keeping the geometrical relationship of the cyclitol and adenine rings, which is critical for the electron-rich adenine ring to interact with positively charged residues in the IBC and presumably Arg504. The exposed cis-diols in InsAdA are unlikely to have a substantial impact on the binding affinity; however, they may function as versatile handles to attach other groups for further SAR study and antagonist design.

Figure 8.

(a) Equilibrium competition binding to cerebellar membranes using [3H]–IP3 (1.5 nM) and the indicated concentrations of related ligands. Results are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. Summary results in Table 3. (b) Concentration-dependent effects of IP3, AdA, and InsAdA on Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Results (% of Ca2+ content, means ± SEM, n = 6) show Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores of permeabilized HEK-IP3R1 cells evoked by the indicated concentrations of ligands. Summary of the results presented in Table 4. (c) Concentration-dependent effects of InsAdA obtained via two different synthetic routes on Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Results (%, means ± SEM, n = 6) show Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores of permeabilized HEK-IP3R1 cells evoked by the indicated concentrations of InsAdA and “chiral route” InsAdA. There were no significant differences between the ligands in the values for Ca2+ release (%) or pEC50 (P < 0.05). pEC50 = 7.65 ± 0.14 and 7.67 ± 0.14 for InsAdA and “chiral route” InsAdA, respectively. Ca2+ release (%) = 74 ± 2 and 72 ± 3 for InsAdA and “chiral route” InsAdA, respectively. (A) Data for IP3 and AdA (Ca2+ assays) are adapted in part with permission from ref (35). Copyright 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry. (B) Data for IP3 and AdA (binding assays) are adapted in part from ref (36). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society; further permissions related to the material excerpted should be directed to the ACS. (C) Data for InsAda “chiral route” are adapted in part with permission from ref (35). Copyright 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Table 3. Effects of Ligands on [3H]–IP3 Binding to Cerebellar Membranesa.

| ligand | pKd | Kd (nM) | h |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP3 (1) | 8.06 ± 0.03 | 8.71 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| AdA (2) | 8.86 ± 0.14 | 1.38 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| InsAdA (5) | 8.90 ± 0.11 | 1.26 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

Results are means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (pKd and h) and means (Kd) from three independent experiments. Kd, equilibrium dissociation constant; pKd, −log Kd; h, Hill coefficient. There were no significant differences between the ligands in the values for h. The pKd values were significantly different (P < 0.05), for IP3 vs AdA and IP3 vs InsAdA. Values for IP3 and AdA (as all ligands were run in parallel in binding assays) are from ref (36).

In assays of Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores of permeabilized HEK cells expressing only IP3R1 (HEK-IP3R1 cells), maximally effective concentrations of IP3, AdA, or InsAdA released the same fraction (∼70%) of the intracellular Ca2+ stores. However, InsAdA was more potent than either AdA or IP3 (Figure 8b and Table 4). The potency of InsAdA was the same as that determined for compounds obtained via a totally chiral synthetic route (“chiral route” InsAdA, Figure 8c).35 IP3 and AdA are full agonists;94 we therefore used the ratio of the concentrations of ligand required to evoke half-maximal Ca2+ release (EC50) and to occupy 50% of IP3Rs (equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd), the EC50/Kd ratio, as an indication of agonist efficacy, which is the ability of the ligand to activate the IP3R once it has bound to it. The EC50/Kd ratios were similar for all three ligands (Table 5), suggesting that InsAdA is a full agonist of IP3R.

Table 4. Effects of Ligands on Ca2+ Release from the Intracellular Stores of Permeabilized HEK-IP3R1 Cellsa.

| ligand | pEC50 | EC50 (nM) | Ca2+ release (%) | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP3 (1) | 6.73 ± 0.13 | 186 | 73 ± 2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| AdA (2) | 7.45 ± 0.16 | 35 | 71 ± 3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| InsAdA (5) | 7.65 ± 0.14 | 22 | 74 ± 2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

Results are means ± SEM (pEC50, Ca2+ release (%), and h) and means (EC50) from six independent experiments each performed in duplicate. EC50, half-maximally effective concentration. There were no significant differences between the ligands in the values for Ca2+ release (%) or h. The pEC50 values were significantly different (P < 0.05) for IP3 vs AdA, IP3 vs InsAdA, and AdA vs InsAdA. Values for IP3 and AdA are taken from ref (35).

Table 5. EC50/Kd Ratios of IP3, AdA, and InsAdAa.

| ligand | EC50/Kd (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| IP3 (1) | 22 (8–59) |

| AdA (2) | 25 (6–100) |

| InsAdA (5) | 18 (6–58) |

EC50/Kd ratio is used as an indication of efficacy. There were no significant differences between the ligands in the values for the EC50/Kd ratios (mean with 95% confidence interval, n = 6), suggesting that like IP3 and AdA, InsAdA is a full agonist of the IP3R.

Thus, we have shown that a convergent synthetic route can achieve the target InsAdA, fully active in two biological assays, using the intrinsic chirality of a d-ribose building block and without an early resolution step. InsAdA prepared by this route is biologically equipotent with that from the synthetic route using only chiral precursors.35 Now that the high potency of InsAdA has been reaffirmed, this ligand also provides importantly and, unlike its parent AdA, an axial cyclitol hydroxyl group for potential further synthetic elaboration. As will be noted from the position of the pyranoside oxygen of AdA in the binding model in Figure 2a, its replacement with an axial hydroxyl,35 if mirrored by InsAdA binding, should offer through suitably substituted derivatives, the potential for direct targeting of the IBC clam cleft that may be useful in the future antagonist design.

It is naturally tempting to speculate why InsAdA is slightly more potent than AdA and how this might relate to the simple replacement of a glucose with chiro-inositol. This is clearly the first example of such an analogue, and even though this might be viewed as a relatively conservative modification, the consequences at an SAR level are likely to be multifactorial and the SAR profiles rehearsed above may not be definitive enough to rationalize its activity. This may best be tackled when further such InsAdA analogues with modifications to the chiro-inositol ring are synthesized and evaluated biologically. Activity ideally needs to be benchmarked to more members of a closely related structural series and perhaps also in concert with studies on IP3R-binding site mutants. For the present, however, we might reasonably assume that InsAdA could bind in a similar fashion to AdA, with its vicinal bisphosphates engaging the same receptor elements as for AdA and IP3 and its adenine still interacting specifically with Arg504 as for AdA, and according to our working model (Figure 2b). Previously rehearsed possibilities for mimicry of the 1′-phosphate of IP3 by the 2″-phosphate of AdA involving Arg56814,17 of the α-domain may also be valid. Conformational flexibility, however, is likely to be impacted through the broad structural change initiated in InsAdA. We should also note that InsAdA represents two pharmacophoric components conjoined through an ether linkage and not via the disaccharide linkage of AdA. Overall conformation might be influenced by exo-anomeric and other steric effects different from AdA and conformational populations presented to the IP3R could differ between the two ligands. For the present, it is encouraging to note that the high potency of AdA has been closely maintained in the new analogue, which importantly offers slightly more synthetic diversity for development. Thus, the potential for using InsAdA to design further ligands of interest is recognized, although the obvious difficulty and length of the synthetic procedures to access InsAdA analogues may well be a limiting factor in progressing this series.

Conclusions

We have developed an alternative synthetic strategy for InsAdA (5), a molecule that combines many structural features of IP3, the native ligand of IP3R, with AdA, the most potent agonist of IP3R. The core structural template with a d-chiro-inositol tethered to a ribonucleoside via a sec–sec ether linkage is rarely found in the literature. The chiro-inositol-ribonucleoside diastereoisomers (31, 32) from coupling of a suitably protected and activated racemic myo-inositol building block to a suitably protected ribose derivative were successfully separated after purine glycosidation and partial deprotection; the desired d-chiro-inositol-ribonucleoside conjugate (31), after configurational assignment, was subsequently converted to the target compound through monobenzylation of the vicinal inositol trans-diol, amination of chloropurine, PMB removal, pan-phosphorylation, and finally full deblocking of all protection. InsAdA was shown to be a high-affinity full agonist of IP3R1, more potent than AdA 2 in releasing Ca2+ from intracellular stores and equipotent to the same material synthesized via a totally chiral route.35 InsAdA is the most potent simple IP3R agonist known and provides a novel structural template for further exploitation of potential IP3R agonists/antagonists. In particular, future synthetic elaboration of the axial hydroxyl of InsAdA could provide high potency ligands that may directly target the IBC cleft and thus offer a novel approach to ligand design not achievable with AdA. A full understanding of the activity of InsAdA must ideally await the synthesis of further members of this new structural series but, most encouragingly, the corresponding d-chiro-inositol ribophostin analogue (Figure 1, compound 4a) has already shown unusually high potency in comparison to ribophostin, its disaccharide counterpart.36

Experimental Section

Materials for Biological Analyses

HEK-293 cells in which the genes for all three IP3R subtypes had been disrupted using the CRISPR-Cas9 technique (HEK-3KO)2 were from Kerafast (Boston). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient mixture F-12 with GlutaMAX (DMEM/F-12 GlutaMAX) and Mag-fluo-4 AM were purchased from Thermo Fisher. G418 was from Formedium (Norfolk, U.K.). TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent was from Geneflow (Elmhurst, Lichfield, U.K.). Most chemicals and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, U.K.). IP3 was from Enzo (Exeter, U.K.) and [3H]–IP3 was from PerkinElmer. Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) was from Tocris (Bristol, U.K.). Half-area 96-well black-walled plates were from Greiner.

[3H]–IP3 Binding

Cerebellar membranes, which are enriched in IP3R1, were prepared from the cerebella of adult Wistar rats as previously described.94 Equilibrium competition binding assays (4 °C, 5 min) were performed in medium (500 μL) comprising 50 mM Tris, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 8.3 with 3H–IP3 (19.3 Ci/mmol, 1.5 nM), cerebellar membranes, and competing ligands.94 Bound and free ligands were separated by centrifugation (20 000g, 5 min, 4 °C). Nonspecific binding, determined by the addition of 10 μM IP3 or by extrapolation of competition curves to infinite IP3 concentration, was <10% of total binding.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 GlutaMAX medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C in 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged or used for experiments when they reached confluence. HEK cells expressing only IP3R1 (HEK-IP3R1 cells) were generated by transfecting HEK-3KO cells with the gene encoding rat IP3R1 (lacking the S1 splice site) cloned into pcDNA3.1(−)/Myc-His B plasmid using TransIT-LT1 reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions. To generate stable cell lines, cells were passaged 48 h after transfection in a medium with G418 (1 mg/mL) and the selection was maintained for 2 weeks. Monoclonal cell lines were selected by plating cells (∼1 cell/well) into 96-well plates in a medium containing G418 (1 mg/mL). After 4 days, wells with only one cell were identified, and cells were grown to confluence. After expansion, expression of IP3R1 was confirmed by western blotting using an antibody specific for IP3R1.94

Ca2+ Release from Intracellular Stores

Mag-fluo 4, a low-affinity fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, was used to monitor free [Ca2+] within the ER lumen93 of HEK-IP3R1 cells. Cells were loaded with an indicator by incubating cells with Mag-fluo 4 AM (20 μM, 60 min, 22 °C) in N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered saline (HBS; 135 mM NaCl, 5.9 mM KCl, 11.6 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 11.5 mM glucose, 1.2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.3) as described.95 After washing and permeabilization with saponin (10 μg/mL, 37 °C, 2–3 min) in Ca2+-free cytosol-like medium (Ca2+-free CLM), cells were centrifuged (650g, 3 min) and incubated for 7 min in Ca2+-free CLM to ensure stores were fully depleted of Ca2+. Cells were further centrifuged (650g, 3 min) and resuspended in Mg2+-free CLM supplemented with CaCl2 to give a final free [Ca2+] of 220 nM after the addition of 1.5 mM MgATP. Ca2+-free CLM comprised 20 mM NaCl, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 20 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES), and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0. Cells (∼3 × 106/well) were attached to poly-l-lysine-coated 96-well black-walled plates (Greiner Bio-One, Stonehouse, U.K.), and fluorescence (excitation and emission at 485 and 520 nm, respectively) was recorded at intervals of 1.44 s using a FlexStation III plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). MgATP (1.5 mM) was added to initiate Ca2+ uptake, and when the ER had loaded to steady state (∼2.5 min), cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μM) was added to inhibit the ER Ca2+ pump. IP3 and related ligands were added after a further 60 s. The amount of Ca2+ released was calculated as a percentage of the fluorescence signal from fully loaded stores (Ffull) minus the signal from nonloaded stores (Ffull – Fempty).

Chemistry

Chemical reagents were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, U.K.) or Alfa Aesar (Heysham, U.K.). AR-grade solvents and anhydrous solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, U.K.) or Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, U.K.) and used as supplied unless specified individually. Superdry DCM and MeCN were prepared by distillation over CaH2 and stored over 3 Å molecular sieves. (±)-1,2:4,5-Di-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (21) was synthesized from myo-inositol following a literature process.40,41 The ribose analogue 28 was prepared using methods reported previously.35 Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using precoated plates (Merck aluminum sheets silica 60 F254) and visualized under a UV lamp (254 nm) and/or by staining in ethanolic phosphomolybdic acid (PMA) or aqueous potassium permanganate (KMnO4), followed by heating. Flash column chromatography was performed on a CombiFlash Rf Automated Flash Chromatography System (Teledyne Isco, Lincoln, NE) equipped with a UV detector using RediSep Rf disposable silica gel columns or high-performance GOLD silica columns. Analytical HPLC analyses were carried out on a Waters 2695 Alliance module equipped with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector (210–350 nm). The chromatographic system consisted of a Hichrom Guard Column for HPLC and a Phenomenex Synergi 4 μm MAX-RP 80 Å column (150 × 4.60 mm2), eluted at 1 mL/min with 0.05 M TEAB–MeCN (95:5 → 35:65 v/v) over 15 min. Semipreparative HPLC purifications were carried out on a Waters 2525 Binary Gradient Module with flex inject equipped with a Waters 2487 dual-wavelength detector. The chromatographic system consisted of a Security Guard Column for HPLC and a Phenomenex Gemini 5 μm C18 110 Å column (250 × 10 mm2), eluted at 5 mL/min with 0.1 M TEAB–MeCN (95:5 → 35:65 v/v) over 25 min. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVIII HD 400 spectrometer at 400, 100, and 162 MHz, respectively. 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra of compound 5 were recorded with a Bruker Avance III HD 500 MHz Spectrometer at 500, 126, and 202 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the solvent residual peaks as internal standards. (1H NMR: CDCl3 7.26 ppm; acetone-d6 2.05 ppm; dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 2.50 ppm; methanol-d4 3.31 ppm; D2O 4.79. 13C NMR: CDCl3 77.16 ppm; acetone-d6 29.84 ppm; DMSO-d6 39.52 ppm). All NMR data were collected at 23 °C. High-resolution time-of-flight mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent single quadrupole spectrometer with CTC-PAL autosampler or a Bruker Daltonics micrOTOF mass spectrometer using electrospray ionization (ESI).

dl-1,2:4,5-Di-O-isopropylidene-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-myo-inositol (22)

To a mixture of 1-(p-toluenesulfonyl)-imidazole (4.16 g, 18.7 mmol) and 21 (4.8 g, 18.5 mmol) in DMF (20 mL) was added CsF (3.372 g, 22.2 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt under argon for 18 h and evaporated in vacuo. The resulting syrup was partitioned between CH2Cl2 (400 mL) and water (400 mL), and the organic layer was filtered through a bed of celite and evaporated to provide a white solid (6.91 g) that was identified by 1H NMR as a mixture of monotosylate (yield 74%) and ditosylate (yield 12%). The mixture was dissolved in DMF (40 mL). NaH (95%, 413 mg, 16.5 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. p-Methoxybenzyl chloride (2.32 g, 15.1 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 16 h. Water (200 mL) was added to the mixture, and the solid was collected and partitioned between DCM (200 mL) and water (200 mL). The organic solution was filtered through a bed of celite, dried, and evaporated. The resulting solid was washed with EtOAc/petroleum ether (4:1) to give an off-white solid (7.04 g). The above-described material and magnesium powder (6.58 g, 274.2 mmol) in MeOH (200 mL) and DCM (200 mL) were stirred in a flask with a reflux condenser. After 20–30 min, the solvent temperature was increased to reflux. The mixture was stirred for another 3 h cooling to rt. The solvents were then evaporated to dryness to give a light-gray solid, which was suspended in DCM (400 mL). HCl solution (0.2 M, 200 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a bed of celite and washed with DCM. The organic solvent was separated from the aqueous layer, and the solvent was evaporated to give a white solid. The remaining celite/magnesium salt mixture was air-dried overnight and further washed with DCM and dried (MgSO4). The combined mixture was then purified by flash column chromatography (DCM to DCM/EtOAc 1:1) to afford compound 22 (4.39 g, 63% overall from 21). 1H and 13C NMR data were identical to the previously reported data for the material prepared by the chiral route.35

dl-3-O-Trifluoromethylsulfonyl-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-1,2:4,5-di-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (23)

Compound 22 (4.39 g, 11.5 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (55 mL) and pyridine (5 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Trifluoromethane sulfonic anhydride (13.8 mL, 13.8 mmol, 1 M in CH2Cl2) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at 0 °C and then warmed up to rt for 2 h. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (200 mL), washed with water (200 mL), and brine was added (20 mL). The organic layer was dried by filtration through solid NaCl and concentrated in vacuo to give compound 23 as a pale beige amorphous solid (5.72 g, 97%). 1H and 13C NMR data were identical to the previously reported data for the material prepared by the chiral route.35

3-O-[2′,3′:5′,6′-O-Diisopropylidene-4′-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-dl-chiro-inosityl]-5-O-benzyl-β-d-ribofuranose-1,2-pent-4-enyl orthobenzoate (29a, 29b)

To a solution of 28(35) (740 mg, 1.79 mmol) in dry THF (3 mL) was added dry hexamethylphosphoramide (8 mL), followed by NaH (90 mg, 95%, 3.6 mmol). The mixture was stirred under argon at rt for 20 min and cooled to 0 °C. (±)-1,2:4,5-Di-O-isopropylidene-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-3-O-trifluoromethane sulfonyl-myo-inositol (±-23, 1.2 g, 2.34 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h and concentrated in vacuo. The mixture was then partitioned between ethyl ether (80 mL) and saturated ammonium chloride solution (60 mL). The organic solution was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The crude product was purified using a Combiflash and eluted with a solvent gradient of petroleum ether to 20% EtOAC/petroleum ether to give a clear oil. (1.1 g, 79%). 1H NMR indicated the two diastereoisomers were in a 1:1 ratio. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.62–7.67 (m, 2 × 2H), 7.25–7.36 (m, 2 × 10H), 6.86 (dt, 2 × 2H, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz), 6.08 (d, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 5.99 (d, 1H, J = 4.1 Hz), 5.77 (m, 2 × 1H), 5.02 (dd, 1H, J = 4.3, 1.9 Hz), 4.97 (dd, 1H, J = 4.6, 2.0 Hz), 4.93–4.96 (m, 2 × 1H), 4.90–4.93 (m, 2 × 1H), 4.76 (s, 2H), 4.74 (s, 2H), 4.60 (d, 1H, J = 12.2 Hz), 4.51 (s, 2H), 4.46 (d, 1H, J = 12.1 Hz), 4.32–4.39 (m, 2 × 2H), 4.23 (t, 1H, J = 2 Hz), 4.09–4.21 (m, 1H + 2 × 2H), 4.00 (dd, 1H, J = 9.3, 4.9 Hz), 3.92 (t, 1H, J = 10.0 Hz), 3.80 (br s, 2 × 3H), 3.74 (t, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 3.71 (t, 1H, J = 2.8 Hz), 3.57–3.66 (m, 2 × 2H), 3.52 (dd, 1H, J = 11, 5.5 Hz), 3.49 (dd, 1H, J = 11.5, 5.0 Hz), 3.31–3.43 (m, 2 × 2H), 2.09 (m, 2 × 2H), 1.59–1.69 (m, 2 × 2H), 1.56 (s, 3H), 1.48 (s, 3H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.30 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C44H55O12 775.3688, found 775.3712.

6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[2″,3″:5″,6″-di-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-dl-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (30a, 30b)

6-Chloro-9-(trimethylsilyl)-9H-purine was prepared by refluxing 6-chloropurine (284 mg, 1.8 mmol) in hexamethyldisilazane (8 mL) for 1.5 h, followed by concentration in vacuo. The yellow residue was mixed with acetonitrile (4 mL) and added to a solution of the diastereoisomers 29a and 29b (1.0 g, 1.3 mmol) in acetonitrile (4 mL) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred over molecular sieves (3 Å, 500 mg) at 0 °C for 20 min. A solution of Yb(OTf)3 (360 mg, 0.58 mmol) and N-iodosuccinimide (450 mg, 2 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 mL) was also stirred with molecular sieves (3 Å, 500 mg) at room temperature for 20 min. The two suspensions were mixed and stirred under argon at room temperature for 24 h. DCM (50 mL) was added, and the mixture was partitioned between DCM (100 mL) and sodium bisulfate solution (4%, 60 mL). The organic solution was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The crude product was purified with a CombiFlash and eluted with a solvent gradient of DCM to 20% EtOAC/DCM to give a white foamy product (0.78 g, 78%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.76 (s, 1H), 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.69 (s, 2 × 1H), 8.12 (dd, 2H, J = 8.2, 1.2 Hz), 8.06 (dd, 2H, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz), 7.65 (ddd, 2 × 1H, J = 8.6, 4.9, 2.4 Hz), 7.50 (td, 2 × 2H, J = 7.8, 1.9 Hz), 7.44 (t, 2 × 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.38 (td, 2 × 2H, J = 7.8, 7.3, 1.8 Hz),7.32 (m, 1H), 7.28 (m, 1 + 2 × 2H), 6.89 (dd, 2 × 2H, J = 8.6, 1.8 Hz), 6.62 (dd, 2 × 1H, J = 6.7, 5.0 Hz), 6.29 (t, 1H, J = 4.6 Hz), 6.17 (t, 1H, J = 5.5 Hz), 5.21 (t, 1H, J = 5.3 Hz), 4.96 (dd, 1H, J = 5.0, 3.1 Hz), 4.76 (d, 2 × 1H, J = 12.2 Hz), 4.69–4.73 (m, 2 × 1H), 4.67 (m, 1H), 4.65 (s, 2H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 4.59 (dt, 1H, J = 5.8, 3.1 Hz), 4.47 (d, 2 × 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.42 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 4.38 (dd, 1H, J = 5.6, 2.1 Hz), 4.12 (t, 1H, J = 5.8 Hz), 4.08 (t, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.00 (td, 2 × 1H, J = 11.0, 3.1 Hz), 3.88–3.96 (m, 2 × 2H), 3.78 (s, 2 × 3H), 3.68–3.75 (m, 2 × 1H), 3.60 (ddd, 2 × 1H, J = 10.2, 6.2, 1.2 Hz), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 3H), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C44H48ClN4O11 843.3003, found 843.3026.

6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-d-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (31) and 6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-l-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (32)

To a solution of the diastereoisomers 30a and 30b (1.2 g, 1.45 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (25 mL) was added ethylene glycol (144 mg, 2.3 mmol), followed by pTSA (25 mg). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min and partitioned between DCM (50 mL) and 5% NaHCO3 (50 mL). The organic solution was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give a foam (1.1 g). The crude product was divided into 300 mg portions, and each portion was subjected to repeated flash chromatography and eluted with a gradient solvent of DCM to 15% acetone/DCM. Compound 31, the less polar product on TLC (40% acetone/DCM), was obtained as a clear oil (480 mg, 42%). The compound was identified as the d-chiro-inositol derivative (31) by comparing the NMR spectra with those of the same material prepared by the chiral route.34 [α]D23 = +4.0° (c = 0.5; CH3CN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 7.99–8.15 (m, 2H), 7.63 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.2, 1.2 Hz), 7.46–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.39– 7.44 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.33 (m, 3H), 6.87 (dt, 2H, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz), 6.60 (d, 1H, J = 4.5 Hz), 6.15 (t, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.16 (t, 1H, J = 5.0 Hz), 4.76 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.76 (d, 1H, J = 12.0 Hz), 4.70 (dd, 1H, J = 12.0, 7.5 Hz), 4.64 (d, 1H, J = 11.5 Hz), 4.57 (dt, 1H, J = 5.0, 3.1 Hz), 4.44 (dd, 1H, J = 6.7, 5.3 Hz), 4.25 (dd, 1H, J = 8.2, 6.6 Hz), 4.10 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz), 4.08 (dd, 1H, J = 5.3, 2.6 Hz), 3.99 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 2.9 Hz), 3.92 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5.0, 3.5 Hz), 3.92 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 3.80 (ddd, 1H, J = 5.6, 4.0, 2.6 Hz), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.69–3.75 (m, 1H), 3.39 (t, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3H). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C41H44ClN4O11 803.2690, found 803.2718. Compound 32, the more polar product on TLC (40% acetone/DCM), was obtained as a clear oil (500 mg, 43%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 7.99–8.14 (m, 2H), 7.64 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz), 7.57–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.27 (d, 1H, J = 8.9 Hz), 6.80–6.91 (m, 2H), 6.61 (d, 1H, J = 5.7 Hz), 6.07 (t, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 5.05 (dd, 1H, J = 5.2, 3.7 Hz), 4.72 (d, 2H, J = 11.6 Hz), 4.71 (s, 2H), 4.67 (d, 1H, J = 3.3 Hz), 4.60 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.24–4.27 (m, 1H), 4.22 (d, 1H, J = 5.7 Hz), 4.21 (d, 1H, J = 5.7 Hz), 4.14 (dd, 1H, J = 3.5, 1.9 Hz), 4.04 (dd, 1H, J = 7.3, 5.8 Hz), 3.99 (dd, 1H, J = 10.5, 3.1 Hz), 3.94 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 3.1 Hz), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.72–3.75 (m, 2H), 1.31 (s, 4H), 1.04 (s, 3H). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C41H44ClN4O11 803.2690, found 803.2662.

Monobenzylation Model Reaction: dl-1,4,6-Tri-O-benzyl-2,3-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (35) and dl-1,4,5-Tri-O-benzyl-2,3-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (36)

To a solution of 33(96) (200 mg, 0.50 mmol) in dry CH3CN (25 mL) was added Bu2SnO (390 mg, 1.1 mmol). The mixture was refluxed in a flask equipped with a Soxhlet extractor containing molecular sieve powder (3 Å) under nitrogen. After 15 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. DMF (5 mL) was added to the residue, followed by CsF (266 mg, 1.75 mmol), TBAI (37 mg, 0.09 mmol), molecular sieves (3 Å, 120 mg), and BnBr (0.18 mL, 1.47 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature under argon for 18 h, diluted with DCM (50 mL), and filtered through celite. The filtrate was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give a clear oil. The crude product was subjected to flash chromatography and eluted with a gradient solvent of petroleum ether to 60% EtOAc/petroleum ether. Compound 35, the less polar product on TLC (50% EtOAc/petroleum ether), was obtained as a clear oil, which turned into a waxy solid (140 mg, 57%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.17–7.50 (m, 15H), 4.88 (d, 1H, J = 11.9 Hz), 4.81 (s, 2H), 4.79 (d, 1H, J = 11.7 Hz), 4.76 (d, 1H, J = 10.8 Hz), 4.71 (d, 1H, J = 11.2 Hz), 4.53 (dd, 1H, J = 6.0, 3.7 Hz), 4.22 (d, 1H, J = 3.7 Hz), 4.19 (dd, 1H, J = 7.0, 6.0 Hz), 3.82 (dd, 1H, J = 7.4, 3.7 Hz), 3.73 (t, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz), 3.70 (d, 1H, J = 7.0 Hz), 3.58 (ddd, 1H, J = 9.8, 7.6, 4.1 Hz), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H). Compound 36, the more polar product on TLC (50% EtOAc/petroleum ether), was obtained as a clear oil, which solidified into a waxy solid (40 mg, 16%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.25–7.45 (m, 15H), 4.86 (d, 1H, J = 11 Hz), 4.85 (d, 1H, J = 10.8 Hz), 4.79 (d, 1H, J = 11.8 Hz), 4.77 (s, 2H), 4.76 (d, 1H, J = 11.8 Hz), 4.55 (dd, 1H, J = 5.7, 3.8 Hz), 4.38 (d, 1H, J = 3.5 Hz), 4.22 (dd, 1H, J = 6.9, 5.7 Hz), 4.01 (td, 1H, J = 8.5, 3.9 Hz), 3.73 (m, 2H), 3.38 (t, 1H, J = 9.3 Hz), 1.44 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H). Starting material 33 was recovered as a white solid (35 mg, 17%).

6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[2″-O-benzyl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-l-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (37) and 6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[3″-O-benzyl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxy-benzyl)-1″-l-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (38)

The title compounds were prepared from 32 using the same method as that for 35 and 36. Compounds 37 and 38 were obtained as clear oils (an inseparable mixture in ratio of 3:1, 58% yield). 1H NMR signals are from the combination of the two regioisomers. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.70 (s, 0.3H), 8.68 (s, 0.3H), 8.01–8.10 (m, 2 + 0.6H), 7.60–7.70 (m, 1 + 0.3H), 7.46– 7.55 (m, 2 + 0.6H), 7.37–7.44 (m, 2 + 0.6H), 7.22–7.38 (m, 10 + 3H), 6.86 (t, 2 + 0.6H, J = 8.5 Hz), 6.61 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 6.58 (d, 0.3H, J = 5.3 Hz), 6.09 (t, 1 + 0.3H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.08 (dd, 1H, J = 5.2, 4.2 Hz), 5.05 (dd, 1 + 0.3H, J = 5.1, 4.1 Hz), 4.66–4.85 (m, 5 + 1.5H), 4.51–4.61 (m, 2 + 0.6H), 4.41 (d, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.37 (d, 0.3H, J = 4.0 Hz), 4.27 (dd, 1H, J = 6.2, 4.0 Hz), 4.22 (dd, 0.3H, J = 4.3, 2.4 Hz), 4.16 (dd, 1 + 0.3H, J = 7.4, 6.1 Hz), 4.07–4.13 (m, 1 + 0.3H), 3.86–3.99 (m, 3 + 1H), 3.77 (s, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.69 (dd, 0.3H, J = 7.1, 2.4 Hz), 3.59–3.65 (m, 1 + 0.3H), 3.49 (dd, 1H, J = 8.6, 7.5 Hz), 3.41 (t, 0.3H, J = 8.1 Hz), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.30 (s, 2H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 1H).

6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[2″-O-benzyl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-d-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (39) and 6-Chloro-9-{2′-O-benzoyl-5′-O-benzyl-3′-O-[3″-O-benzyl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-d-chiro-inosityl]-β-d-ribofuranosyl}purine (40)

To a solution of diol 31 (150 mg, 0.19 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN (15 mL) was added Bu2SnO (150 mg, 0.60 mmol). The mixture was refluxed in a flask equipped with a Soxhlet extractor containing activated molecular sieve powder (3 Å) under nitrogen. After 18 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. DMF (3 mL) was added to the residue, followed by CsF (150 mg, 0.99 mmol), TBAI (20 mg, 0.05 mmol), molecular sieves (3 Å, 120 mg), and BnBr (0.1 mL, 0.82 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature under argon for 16 h, diluted with DCM (50 mL), and filtered through celite. The filtrate was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give a clear oil. The crude product was subjected to flash chromatography and eluted with a solvent gradient of petroleum ether to 60% EtOAc/petroleum ether. Compound 39, the less polar product on TLC (50% EtOAc/petroleum ether), was obtained as a clear oil (43 mg, 26%). [α]D23 = −3.0° (c = 0.5; CH3CN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.03 (dd, 2H, J = 8.4, 1.3 Hz), 7.62 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz), 7.19–7.47 (m, 14H), 6.87 (dt, 2H, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz), 6.64 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 6.12 (t, 1H, J = 5.0 Hz), 5.12 (t, 1H, J = 4.9 Hz), 4.77 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.64–4.71 (m, 4H), 4.50–4.57 (m, 3H), 4.27–4.32 (m, 2H), 4.08 (dd, 1H, J = 6.4, 2.2 Hz), 4.00 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 2.9 Hz), 3.92 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 3.4 Hz), 3.86 (dd, 1H, J = 7.1, 3.6 Hz), 3.79 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.65 (dd, 1H, J = 3.4, 2.2 Hz), 3.43 (dd, 1H, J = 8.8, 7.0 Hz), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.32 (s, 3H). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C48H50ClN4O11 893.3153, found 893.3161. Compound 40, the more polar product on TLC (50% EtOAc/petroleum ether), was obtained as a clear oil (52 mg, 31%). [α]D23 = +4.3° (c = 0.4; CH3CN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 7.96–8.15 (m, 2H), 7.62 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz), 7.45–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.37 (m, 10H), 6.85 (dt, 2H, J = 8.9, 2.1 Hz), 6.63 (d, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 6.13 (dd, 1H, J = 5.2, 4.3 Hz), 5.18 (t, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.65–4.75 (m, 3H), 4.61 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.57 (dt, 1H, J = 5.7, 3.0 Hz), 4.47 (dd, 1H, J = 7.2, 5.2 Hz), 4.46 (d, 1H, J = 11.2 Hz), 4.43 (d, 1H, J = 11.6 Hz), 4.32 (t, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, J = 3.2 Hz, OH), 3.91–4.02 (m, 4H), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.53 (dd, 1H, J = 7.7, 3.2 Hz), 3.49 (dd, 1H, J = 8.3, 7.2 Hz), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 3H). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C48H50ClN4O11 893.3153, found 893.3160. Starting material 31 was recovered as a clear oil (38 mg, 25%).

3′-O-[2″-O-Benzyl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-4″-O-(p-methoxybenzyl)-1″-d-chiro-inosityl]-5′-O-benzyl adenosine (41)

Ammonia gas was bubbled into a solution of 39 (50 mg, 0.056 mmol) in anhydrous EtOH (8 mL) in a pressure tube at 0 °C for 30 min. The tube was sealed and heated to 78 °C. After stirring for 20 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. The crude product was subjected to flash chromatography and eluted with a solvent gradient of DCM to 5% MeOH/DCM. Compound 41 was obtained as a clear oil (30 mg, 61%). [α]D23 = +3.6° (c = 0.25, CH3CN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.20 (s, 1H), 8.19 (s, 1H), 7.18–7.45 (m, 12H), 6.89 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.63 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.04 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz), 4.90 (d, 1H, J = 11.8 Hz), 4.81 (d, 1H, J = 9.9 Hz), 4.78 (d, 1H, J = 3.8 Hz), 4.77 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 4.61–4.73 (m, 4H), 4.59–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.39 (dd, 1H, J = 5.8, 3.8 Hz), 4.30–4.17 (m, 3H), 4.03 (t, 1H, J = 8.7Hz), 3.85 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 3.3 Hz), 3.78 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.75–3.79 (m, 1H), 3.74 (dd, 1H, J = 8.1, 2.9 Hz), 3.48 (dd, 1H, J = 8.7, 7.4 Hz), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 160.14, 157.17, 153.83, 150.71, 140.03, 139.38, 139.17, 132.18, 130.26, 129.30, 129.20, 129.00, 128.58, 128.52, 128.49, 120.63, 114.31, 110.15, 89.50, 84.69, 82.32, 80.26, 80.15, 79.91, 78.18, 76.47, 74.55, 74.51, 73.99, 73.63, 72.77, 70.23, 55.56, 28.33, 26.30. HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C41H48N5O10 770.3390, found 770.3390.

dl-1,4-Di-O-benzyl-6-O-(para-methoxybenzyl)-2,3-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (45) and dl-1,4-Di-O-benzyl-5-O-(para-methoxybenzyl)-2,3-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (46)

The title compounds were prepared from 33 (300 mg, 0.75 mmol) using the same method as for compounds 35 and 36. Compound 45 was obtained as a waxy solid (230 mg, 59%) 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.20–7.52 (m, 12H), 6.77–6.92 (m, 2H), 4.89 (d, 1H, J = 11.9 Hz), 4.79 (d, 1H, J = 11.9 Hz), 4.75 (d, 1H, J = 11.5 Hz), 4.73 (s, 2H), 4.70 (d, 1H, J = 11.5 Hz), 4.50 (dd, 1H, J = 6.0, 3.6 Hz), 4.18 (dd, 1H, J = 7.0, 6.0 Hz), 4.14 (d, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.68–3.88 (m, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.50–3.61 (m, 1H), 1.45 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 160.09, 140.26, 139.95, 132.18, 130.23, 129.04, 128.92, 128.61, 128.37, 128.18, 128.04, 114.32, 109.98, 83.13, 81.80, 79.89, 78.45, 75.13, 74.87, 74.28, 73.76, 72.95, 55.51, 27.96, 26.02. Compound 46 was obtained as a waxy solid (52 mg, 13%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 7.21–7.47 (m, 12H), 6.73–6.92 (m, 2H), 4.85 (d, 1H, J = 11.8 Hz), 4.77 (s, 2H), 4.70–4.81 (m, 3H), 4.54 (dd, 1H, J = 5.7, 3.8 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, J = 3.5 Hz), 4.20 (dd, 1H, J = 6.9, 5.7 Hz), 3.99 (td, 1H, J = 8.5, 3.6 Hz), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.66–3.75 (m, 2H), 3.35 (dd, 1H, J = 9.3, 8.2 Hz), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 160.04, 140.20, 140.13, 132.34, 130.24, 128.99, 128.92, 128.55, 128.43, 128.13, 128.06, 114.25, 109.89, 83.30, 80.08, 78.86, 74.85, 74.77, 74.06, 73.17, 73.06, 72.81, 55.49, 28.12, 26.04.

PMB Removal Model Reaction: dl-1,4-Di-O-Benzyl-2,3-O-isopropylidene-myo-inositol (33)

To a solution of 45 (60 mg, 0.115 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (5 mL) was added a solution of TFA (0.5 mL) in anhydrous DCM (0.5 mL). After stirring at room temperature for 4 min, the reaction was quenched with Et3N (1 mL) and concentrated to dryness in vacuum. DCM (20 mL) was added to the residue and stirred for 5 min. The mixture was then filtered and rinsed with DCM (2 × 5 mL). The filtrate was evaporated and subjected to flash chromatography and eluted with a gradient solvent of DCM to 70% EtOAc/DCM. Compound 33 was obtained as a white solid (37 mg, 80%). mp 158–158 °C (lit96 160–161 °C). 1H NMR was identical to the standard sample.

3′-O-(2″-O-Benzyl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene)-1″-d-chiro-inosityl]-5′-O-benzyl Adenosine (42)

To a solution of 41 (45 mg, 0.058 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (0.5 mL) was added a solution of TFA (114 mg, 1 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (0.5 mL). After stirring at room temperature for 4 min, the reaction mixture was quenched with NH3–CH3OH (7 N, 2 mL) and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. DCM (20 mL) was added to the residue, and the mixture stirred for 5 min. The mixture was then filtered and solid residue rinsed with DCM (2 × 5 mL). The filtrate was evaporated and subjected to flash chromatography and eluted with a solvent gradient of DCM to 10% MeOH/DCM. Compound 42 was obtained as a clear oil (24 mg, 63%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 8.21 (s, 1H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.21–7.46 (m, 10H), 6.66 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.05 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz), 4.89 (d, 1H, J = 11.8 Hz), 4.81 (d, 1H, J = 11.8 Hz), 4.76 (t, 1H, J = 4.1 Hz), 4.69 (dd, 1H, J = 6.0, 4.9 Hz), 4.64 (d, 1H, J = 12.0 Hz), 4.60 (d, 1H, J = 12.0 Hz), 4.36 (dd, 1H, J = 5.7, 3.7 Hz), 4.27 (dt, 1H, J = 5.7, 3.5 Hz), 4.21 (t, 1H, J = 3.3 Hz), 4.10 (dd, 1H, J = 7.6, 5.7 Hz), 3.90 (t, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 3.85 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 3.3 Hz), 3.77 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 3.8 Hz), 3.70 (dd, 1H, J = 8.4, 3.0 Hz), 3.56 (dd, 1H, J = 8.9, 7.5 Hz), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3COCD3) δ 157.14, 157.0, 153.82, 150.69, 140.01, 139.34, 139.12, 129.28, 129.17, 129.00, 128.55, 128.49, 128.48, 109.94, 89.45, 82.34, 80.23, 80.22, 80.00, 78.29, 77.14, 76.32, 74.53, 74.47, 73.98, 73.22, 70.21, 28.40, 26.30. HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C33H40N5O9 650.2815, found 650.2816.

5′-O-Benzyl-2′-O-dibenzylphosphoryl-6-N-dibenzylphosphoryl-3′-O-(2″-O-benzyl-3″,4″-dibenzylphosphoryl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-1″-d-chiro-inosityl)adenosine (43) and 5′-O-Benzyl-2′-O-dibenzylphosphoryl-3′-O-(2″-O-benzyl-3″,4″-dibenzylphosphoryl-5″,6″-O-isopropylidene-1″-d-chiro-inosityl)adenosine (44)

The mixture of imidazolium triflate (44 mg, 0.2 mmol) and bis(benzyloxy)diisopropylamino-phosphine (66 mg, 0.19 mmol) in DCM (0.75 mL) and CD2Cl2 (0.75 mL) was stirred under argon at room temperature. After 20 min, the solution was added to a flask containing compound 42 (24 mg, 0.037 mmol). The mixture was stirred for another 1 h under the same conditions. 31P NMR spectroscopy indicated reaction completeness. The reaction was quenched by adding a drop of water and cooled to −78 °C. tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (0.3 mL, 70% water solution) was added, and the mixture was brought to room temperature. After stirring for 30 min, the reaction was quenched by adding Na2SO3 (5 mL, 10% water solution), followed by DCM (60 mL). After separation, the organic phase was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give a clear oil. The crude product was subjected to flash chromatography and eluted with a solvent gradient of DCM to 7% MeOH/DCM. Compound 43 was obtained as a clear oil (25 mg, 40%). [α]D23 = −5.5° (c = 0.22, CH3CN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3): δ 8.67 (br, 1H, NH), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.40 (s, 1H), 7.18–7.44 (m, 50H), 6.39 (d, 1H, J = 4.6 Hz), 5.62 (dt, 1H, J = 8.0, 4.7 Hz), 5.22–5.32 (m, 4H), 5.06–5.19 (m, 8H), 4.99 (dd, 2H, J = 8.7, 1.9 Hz), 4.92 (dd, 2H, J = 8.3, 2.4 Hz), 4.83 (t, 1H, J = 4.7 Hz), 4.69–4.76 (m, 4H), 4.60–4.67 (m, 3H), 4.51 (dd, 1H, J = 9.4, 7.1 Hz), 4.46 (dd, 1H, J = 4.9, 2.7 Hz), 4.44 (d, 1H, J = 1.8 Hz), 4.22 (dd, 1H, J = 6.7, 2.1 Hz), 3.89 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 2.7 Hz), 3.82 (dd, 1H, J = 11.0, 3.3 Hz), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H). 31P NMR (162 MHz, 1H-decoupled, CD3COCD3): δ −0.90, −1.17, −1.50, −1.50. HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C89H92N5O21P4 1690.5225, found 1690.5187. Compound 44 was obtained as a glassy residue (17 mg, 32%). [α]D23 = −10.0° (c = 0.15; CH3CN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3): δ 8.20 (s, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H,), 7.19–7.44 (m, 40H), 6.65 (br, 2H, NH2), 6.39 (d, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 5.60 (dt, 1H, J = 7.9, 4.7 Hz), 5.04–5.22 (m, 8H), 4.99 (s, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H), 4.91 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 4.89 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz), 4.81 (t, 1H, J = 4.7 Hz), 4.63–4.75 (m, 7H), 4.51 (dd, 1H, J = 9.4, 7.1 Hz), 4.44 (dt, 2H, J = 6.5, 2.3 Hz), 4.22 (dd, 1H, J = 6.8, 2.1 Hz), 3.88 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 2.8 Hz), 3.81 (dd, 1H, J = 10.9, 3.3 Hz), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.26 (s, 3H). 31P NMR (162 MHz, 1H-decoupled, CD3COCD3): δ −1.26, −1.51, −1.53. HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M + H]+ C75H79N5O18P3 1430.4622, found 1430.4594.

3′-O-(1″-d-chiro-Inosityl)adenosine 2′,3″,4″-trisphosphate (d-chiro-Inositol adenophostin) (5)

To a solution of 43 (23 mg, 0.013 mmol) in methanol–water (4–0.5 mL) was added cyclohexene (1 mL), followed by Pd(OH)2 (80 mg, 20% Pd on charcoal, 50% water). The mixture was refluxed for 18 h, cooled to room temperature, and filtered through a syringe membrane filter (Whatman, PTEF-S, 0.2 μm). The filter was washed repeatedly with methanol–water. The filtrate was evaporated in vacuo at 35 °C to give a clear residue (8 mg, 78%). The product was subjected to purification on a semiprep HPLC system. Appropriate fractions identified by analytical HPLC were collected, evaporated in vacuo, and then coevaporated with water (×2) to give the title compound in TEAB salt form as a colorless glass (4.8 μmol by UV quantification at the max wavelength of 259 nm, 37% yield for deprotection and purification). 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 6.21 (d, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz), 5.31 (dt, 1H, J = 7.7, 5.5 Hz), 4.61 (q, 2H, J = 9.6 Hz), 4.28 (q, 1H, J = 9.0 Hz), 4.23 (q, 1H, J = 3.0 Hz), 3.92–4.11 (m, 4H), 3.86 (dd, 1H, J = 12.4, 3.0 Hz), 3.75 (dd, 1H, J = 12.5, 3.1 Hz). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 157.45, 153.55, 150.52, 142.14, 120.83, 89.63, 86.78, 81.40, 80.93, 78.64, 78.12, 76.80, 73.08, 72.88, 71.82, 63.52. 31P NMR (202 MHz, 1H-decoupled, MeOD): δ 2.75 (s), 1.54 (s), 0.54 (s). 31P NMR (202 MHz, 1H-coupled, MeOD) δ 2.76 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 1.54 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 0.54 (d, J = 7.9 Hz). HRMS-ESI (m/z) required for [M – H]− C16H25N5O18P3 668.0413, found 668.0415; UV (H2O, pH 7), λmax 259 nm (ε 15 400).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust. BVLP and CWT are Wellcome Trust Senior Investigators (grant nos. 101010 and 101844, respectively). A.M.R. is a Fellow at Queens’ College, Cambridge. We thank Dr. A. M. Riley for highly constructive discussions during this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- IP3R

d-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- IP3

d-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- AdA

glyconucleotide adenophostin A

- InsAdA

d-chiro-inositol adenophostin

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- IBC

IP3-binding core

- PMB

p-methoxybenzyl

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- CAN

ceric ammonium nitrate

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- TBAI

tetrabutylammonium iodide

- DDQ

2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-p-benzoquinone

- TMSOTf

trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate

- pTSA

toluene-4-sulfonic acid

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c04145.

1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra for all novel compounds and intermediates; high-resolution MS; and HPLC data (PDF)

Author Contributions

X.S., W.D., and S.J.M. contributed equally to this work. B.V.L.P. conceived and designed the overall study with focused chemical strategies elaborated by X.S., W.D., and S.J.M. X.S. and W.D. synthesized and characterized all compounds. J.M.W. purified and characterized the final compound. A.M.R. performed Ca2+ flux and binding assays with C.W.T. X.S. and B.V.L.P. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supporting Information files.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rossi A. M.; Taylor C. W. IP3 receptors - lessons from analyses ex cellula. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 132, jcs222463 10.1242/jcs.222463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzayady K. J.; Wang L.; Chandrasekhar R.; Wagner L. E. 2nd; Van Petegem F.; Yule D. I. Defining the stoichiometry of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate binding required to initiate Ca2+ release. Sci. Signaling 2016, 9, ra35 10.1126/scisignal.aad6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosanac I.; Alattia J.-R.; Mal T. K.; Chan J.; Talarico S.; Tong F. K.; Tong K. I.; Yoshikawa F.; Furuichi T.; Iwai M.; Michikawa T.; Mikoshiba K.; Ikura M. Structure of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding core in complex with its ligand. Nature 2002, 420, 696. 10.1038/nature01268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter B. V. L.; Lampe D. Chemistry of Inositol Lipid Mediated Cellular Signaling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1995, 34, 1933–1972. 10.1002/anie.199519331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]