Abstract

Recent published studies suggest that increasing levels of ceramides enhance the chemo‐sensitivity of curcumin. Using in vitro approaches, we analyzed the impact of sphingosine kinase‐1 (SphK‐1) inhibition on ceramide production, and evaluated SphK1 inhibitor II (SKI‐II) as a potential curcumin chemo‐sensitizer in ovarian cancer cells. We found that SphK1 is overexpressed in ovarian cancer patients' tumor tissues and in cultured ovarian cancer cell lines. Inhibition of SphK1 by SKI‐II or by RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown dramatically enhanced curcumin‐induced apoptosis and growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells. SKI‐II facilitated curcumin‐induced ceramide production, p38 activation and Akt inhibition. Inhibition of p38 by the pharmacological inhibitor (SB 203580), a dominant‐negative expression vector, or by RNAi diminished curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration‐induced ovarian cancer cell apoptosis. In addition, restoring Akt activation introducing a constitutively active Akt, or inhibiting ceramide production by fumonisin B1 also inhibited the curcumin plus SKI‐II co‐administration‐induced in vitro anti‐ovarian cancer effect, suggesting that ceramide accumulation, p38 activation and Akt inhibition are downstream effectors. Our findings suggest that low, well‐tolerated doses of SKI‐II may offer significant improvement to the clinical curcumin treatment of ovarian cancer. (Cancer Sci, doi: 10.1111/j.1349‐7006.2012.02335.x, 2012)

Curcumin possesses wide‐ranging anti‐inflammatory, anti‐proliferative, anti‐angiogenic and anti‐cancer properties.1, 2 The chemotherapeutic potential of curcumin against ovarian and other cancers3, 4, 5 is due to its ability to induce cancer cell apoptosis, and to inhibit cancer growth and angiogenesis.6 However, the systematic use of curcumin is limited due to the poor bioavailability of curcumin after oral administration.7 As such, finding a curcumin sensitizer is crucial for improving chemo‐efficiency. Recent published studies demonstrate that curcumin induces ceramide generation to promote cancer cell apoptosis,8, 9, 10 and indicate that agents that enhance intracellular ceramide levels would enhance curcumin‐induced tumor cell cytotoxicity and apoptosis.10, 11

Metabolites of sphingolipids have emerged as key signaling molecules in cancer cell progression. Ceramides, sphingosine and sphingosine‐1‐phosphate (S1P) are three major plays of sphingolipids metabolites.12, 13 While ceramides and their precursor sphingosine cause cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, S1P promotes cell growth, proliferation and survival.12, 13 Therefore, the balance between ceramide/sphingosine and S1P levels is critical in determining cell fate. The master kinase that regulates this balance is sphingosine kinase‐1 (SphK1). Increased expression and/or activity of SphK1, which is seen in multiple types of cancer,13, 14, 15, 16, 17 lead to increased S1P levels and decreased sphingolipid/ceramide levels, promoting cancer progression. Inhibitors of SphK1 are expected not only to inhibit S1P production, but also to increase sphingosine/ceramides, pushing cancer cells toward apoptosis.13, 18 Here, we tested the expression level of SphK1 in ovarian tumor tissues and in cultured ovarian cancer cells. Using in vitro approaches, we also analyzed the impact of SphK‐1 inhibition on ceramide production and evaluated SphK1 inhibitor SKI‐II as a potential curcumin chemo‐sensitizer against ovarian cancer.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Curcumin, SKI‐II, fumonisin B1 and SB 203580 were obtained from Sigma (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA); Anti‐Akt1, tubulin, rabbit and mouse IgG‐HRP were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All other antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Bevery, MA, USA).

Cell culture

Ovarian cancer cell lines CaOV3, SKOV3 and A2780 were cultured as previous reported.19, 20 The normal ovarian epithelial cell line, the Moody cell, transfected with hTERT, was obtained from Shanghai Shajing Molecular Biotechnology (Shanghai, China), and was maintained in MCDB109/M199 medium supplemented with 20% FBS.

Clonogenicity assay

Ovarian cancer cells (4 × 104) were suspended in 1 mL of DMEM containing 0.5% agar (Sigma), 10% FBS and with indicated treatments or vehicle controls. The cell suspension was then added on top of a pre‐solidified 1% agar in a 100‐m culture dish. The medium was replaced every 3 days. After 12 days of incubation, colonies were photographed at 4×. Colonies larger than 50 μm in diameter were quantified using Image J Software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html).

Quantification of apoptosis by ELISA, analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide FACS, cell survival assay by “trypan blue“ staining and western blot, cell viability MTT assay, and analysis of cellular ceramide levels

Generation of a CaOV3 line stably expressing a dominant‐negative p38 mutant

The full length of p38 was cloned into pCB7 vector as a HindIIII fragment. This construct served as the template to replace threonine 180 and tyrosine 182 with alanine and phenylalanine, respectively. A C‐terminal FLAG tag was introduced to distinguish between endogenous and transfected p38. The hresulting fragment was cloned into vector pOPI3 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) as an NotI fragment. The p38 insert was sequenced on both strands to confirm the mutation. The plasmid was co‐transfected into CaOV3 with plasmid pCMVLacI (Stratagene), and stable transformants were isolated in the presence of hygromycin (10 μg/mL, Sigma); these p38‐DN CaOV3 were grown in the continuous presence of hygromycin.

Generation of a CaOV3 line stably expressing constitutively active Akt

As previously reported,21 a plasmid encoding a constitutively active Akt1 cDNA (Plasmid 16244) was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA). For transfection experiments, 4.0 μL PLUS Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was diluted in 90 μL of RNA dilution water (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 5 min at room temperature. Then, 2 μg of CA‐Akt plasmid or vector control were added to the PLUS Reagent, which was left for 5 min at room temperature. A total of 3.6 μL of Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) was then added to the complex. After 30 min incubation, the transfection complex was formed and added to each well containing 1.25 mL of medium for 48 h; puromycin (10 μg/mL) were added to select successfully transfected cells.

RNAi and plasmid transfection

SiRNA for SphK1 and p38 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. CaOV3 cells were seeded with 60% confluence. For RNAi experiments, 4.2 μL of PLUS Reagent (Invitrogen) was diluted in 90 μL of RNA dilution water for 5 min in room temperature. Then, 20–40 μL of siRNA (20 μM) or control siRNA (20 μM) was added to PLUS Reagent and left for 5 min at room temperature; 4.5 μL of Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) was added to the complex. After 30 min incubation, the transfection complex was added to the cells. SphK1 and p38 protein expression was determined by western blot 48 h after transfection and only successfully transfected cells were used for further experiments.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was the same as in our previous publication.22 Significance was chosen as P < 0.05. The combination index (CI) was calculated using CalcuSyn software (Version 2.0, purchased from Researchsoft.com.cn, Beijing, China), and CI < 1 indicates synergism.

Results

SphK1 inhibitor SKI‐II sensitizes curcumin‐induced growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells

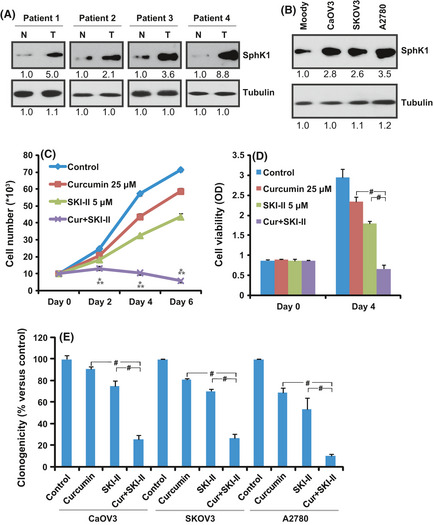

We first examined the expression level of SphK1 in clinical ovarian tumor tissues and in ovarian cancer cells. Ovarian tumor tissues and their surrounding normal ovarian epithelial tissues were surgical removed from five individuals (informed consent was received from these ovarian cancer patients), and were immediately sliced and lysed by tissue lysis buffer, followed by western blot testing for SphK1 and tubulin. We detected overexpressed SphK1 in four of the five ovarian tumor samples (T), compared to their surrounding normal ovarian epithelial tissues (N) (Fig. 1A). SphK1 was also overexpressed in at least three ovarian cancer cell lines (SKOV3, A2780 and CaOV3), compared to the normal ovarian epithelial cells (Moody) (Fig. 1B). We then used CaOV3 as a cell model to study SphK1. The impact of SphK1 inhibitor SKI‐II on curcumin's effect in CaOV3 cells was tested. Results in Figure 1C–E demonstrate that curcumin at 25 μM had a moderate effect on CaOV3 cell growth; adding 5 μM of SKI‐II dramatically enhanced curcumin's effect (Fig. 1C–E). Note that SKI‐II itself only slightly decreased CaOV3 cell proliferation (Fig. 1C–E). MTT results in Figure 1D show a 20.3% reduction in cell viability after 4 days (96 h) of curcumin (25 μM) treatment, and a 39.1% reduction with SKI‐II (5 μM) treatment; a combination the two caused a synergistic 77.3% cell viability loss (P < 0.05 versus control, combination index (CI) < 1). The synergistic anti‐cell proliferation effect of curcumin and SKI‐II was also seen in two other ovarian cancer cell lines, SKOV3 and A2780 (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Sphingosine kinase‐1 (SphK‐1) inhibitor SKI‐II sensitizes curcumin‐induced growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells. (A) Protein expression of SphK1 and tubulin in patients' ovarian tumor samples (T) and surrounding normal ovarian epithelial tissues (N). (B) protein expression of SphK1 and tubulin in normal ovarian epithelial cell line (Moody) and three different ovarian cancer cell lines. Western blot results were quantified by Image J software after normalized to tubulin and were expressed as fold change versus the lane labeled “1.0.” Ovarian cancer cells CaOV3, SKOV and A2780 were either left untreated or exposed to 25 μM of curcumin, 5 μM of SKI‐II or a combination of both agents; cell proliferation was analyzed by cell number count (C), “MTT” cell viability assay (D) and “clonogenicity” assay (E). The values in the figures are expressed as the means ± SD (same for the rest of the figures). All experiments were repeated three times and similar results were obtained (same for the rest of the figures). *P < 0.05 versus curcumin only group; **P < 0.05 versus SKI‐II only group, # P < 0.05. Statistical significance was analyzed by ANOVA (same for the rest of the figures).

SKI‐II sensitizes curcumin‐induced ovarian cancer cells cytotoxicity and apoptosis

CaOV3 cell death after indicated doses of curcumin and/or SKI‐II treatments was also tested by trypan blue staining (Fig. 2A). We decided to set the curcumin concentration at 25 μM and the SKI‐II concentration at 5 μM for further experiments, because at the set concentration each agent alone had a moderate effect on CaOV3 cell death, while a combination of the two caused a significant and synergistic anti‐CaOV3 cell effect. It was found that 25 μM of curcumin caused 13.8% cell death and 5 μM of SKI‐II resulted in 18.7% cell death, while a combination of the two caused 67.8% cell death (CI < 1). For Moody normal ovarian epitherial cells, cytotoxicity assay results in Figure 2B show that curcumin (25 μM) alone or SKI‐II (25 μM) alone had a very limited effect on Moody cell death (curcumin, 3.0% cell death; SKI‐II, 11.2% cell death), and a combination of the two did not significantly enhance cell death (13.9% cell death). SKI‐II and curcumin caused synergistic cell apoptosis in cultured ovarian cancer cells CaOV3 (Fig. 2C,D), SKOV3 and A2780 (Fig. 2D). The apoptosis percentage in CaOV3 cells after SKI‐II (5 μM) plus curcumin (25 μM) treatment increased to 27%, compared to 9% after SKI‐II only treatment and 4% for curcumin only treatment (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

SKI‐II sensitizes curcumin‐induced ovarian cancer cells cytotoxicity and apoptosis. Ovarian cancer cells and normal ovarian Moody cells were either left untreated (control) or exposed to indicated concentration of curcumin, SKI‐II or a combination of both for 48 h. Trypan blue staining was used to determine the percentage of remaining viable cells (A,B). Apoptosis in CaOV3 cells after 32 h of indicated treatments was also quantified of by histone‐DNA ELISA assay (C). Percentage of apoptotic ovarian cells was analyzed 36 h after treatments by FACS sorting PI stained cells (D). For experiments B–D, curcumin concentration is 25 μM and SKI‐II concentration is 5 μM. *P < 0.05 versus curcumin only group; # P < 0.05.

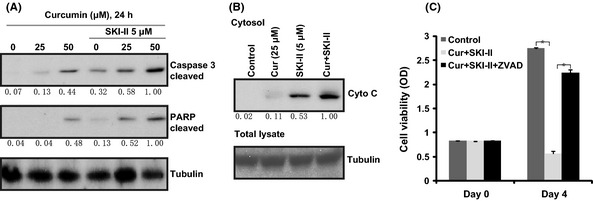

SKI‐II facilitates curcumin‐induced mitochondrial apoptosis pathways to inhibit ovarian cancer cell proliferation

Western blot results show that SKI‐II (5 μM) dramatically enhanced curcumin (25 μM)‐induced caspase 3 and PARP cleavage (Fig. 3A) and cytochrome c release (Fig. 3B). Caspase‐3 inhibitor z‐VAD‐fmk (60 μM) largely inhibited SKI‐II and curcumin co‐administration induced cell viability loss (Fig. 3C), suggesting that SKI‐II and curcumin co‐administration‐induced ovarian cancer cell growth inhibition might be due to caspase‐3 activation and mitochondrial apoptosis.

Figure 3.

SKI‐II facilitates curcumin‐induced mitochondrial apoptosis pathways to inhibit ovarian cancer cell proliferation. CaOV3 ovarian cancer cells were either left untreated (control) or exposed to curcumin (25/50 μM) with or without 5 μM of SKI‐II for 24 h. Cleaved‐caspase‐3, cleaved‐PARP (A), cytosol cytochrome c (B) and tubulin were analyzed by western blot. CaOV3 ovarian cancer cells were either left untreated (control) or exposed to curcumin (25 μM)+SKI‐II (5 μM) (Cur+SKI‐II) with or without z‐VAD‐fmk (ZVAD 60 μM) for 4 days. Cell proliferation was analyzed by “MTT” cell viability assay (C). Western blot results were quantified by Image J software after normalized to tubulin and were expressed as fold change versus the lane labeled “1.0.” *P < 0.05.

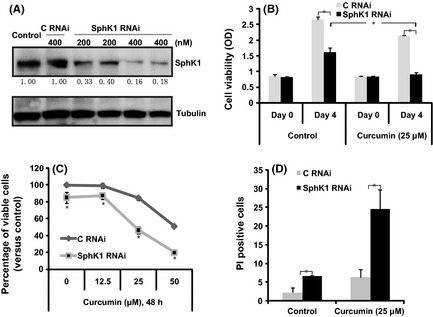

RNAi‐induced SphK1 knockdown sensitizes curcumin induced apoptosis and growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells

SiRNA was used to knock down SphK1 in ovarian cancer cells. Western blot results in Figure 4A show that 400 nM of SphK1 siRNA reduced the expression of SphK1 by 83% in CaOV3 cells, while the same concentration of scramble siRNA (C RNAi) had no effect. SphK1‐knocked‐down CaOV3 cells grew more slowly than scramble siRNA (C RNAi) transfected cells (Fig. 4B left). Knockdown of SphK1 significantly enhanced curcumin‐induced cell viability loss in CaOV3 cells (Fig. 4B right). Furthermore, SphK1 siRNA knockdown cells were more sensitive to curcumin‐induced cell death (Fig. 4C) and apoptosis (Fig. 4D). The curcumin (25 μM)‐induced cell death percentage increased from 15.3% in scramble siRNA transfected cells to 53.7% in SphK1 RNAi cells (Fig. 4C). The cell apoptosis percentage also increased, from 6.3 to 24.6% (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

RNAi‐induced sphingosine kinase‐1 (SphK‐1) knockdown sensitizes curcumin‐induced apoptosis and growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells. CaOV3 cells were transfected with scramble siRNA (C RNAi, 400 nM) or SphK1 siRNA (200/400 nM) for 48 h. Expression level of SphK1 and tubulin were analyzed (A). Scramble siRNA (C RNAi, 400 nM) or SphK1 siRNA (C RNAi, 400 nM)‐transfected CaOV3 ovarian cancer cells were either left untreated or treated with curcumin. Cell proliferation was analyzed by “MTT” assay after 48 h (B), the percentage of viable cells after indicated treatment/s was analyzed by trypan blue staining after 48 h (C) and percentage of apoptosis was analyzed by FACS sorting PI stained cells (D). *P < 0.05.

SphK1 inhibition facilitates curcumin‐induced ceramide production

Consistent with previous findings,10, 21 we observed a moderate ceramide accumulation after 24 h of curcumin (25 μM) treatment in CaOV3 cells (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of SphK1 by SKI‐II (5 μM, 24 h) also increased the ceramide level (Fig. 5A). Significantly, SKI‐II and curcumin synergistically increased the ceramide level (Fig. 5A). Similarly, knockdown of SphK1 by target RNAi increased the basal and curcumin‐induced ceramide level in CaOV3 cells (Fig. 5B). Fumonisin B1 (F‐B1, 25 μM), a de‐novo ceramide synthesis inhibitor,23 largely inhibited curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration‐induced ceramide accumulation (Fig. 5A) and cell apoptosis (Fig. 5C,D). Fumonisin B1 (25 μM) alone had no effect on ceramide accumulation and CaOV3 cell apoptosis (data not shown). We conclude that inhibition of SphK1 facilitated curcumin‐induced ceramide production to mediate ovarian cancer cell apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Sphingosine kinase‐1 (SphK‐1) inhibition facilitates curcumin‐induced ceramide production. Cellular ceramide level in CaOV3 cells with the following treatments: CaOV3 cells were either left untreated (control) or treated with curcumin (25 μM), SKI‐II (5 μM), curcumin+SKI‐II (Cur + SKI‐II), fumonisin B1 (25 μM) + curcumin + SKI‐II (F‐B1 + Cur + SKI) for 24 h, cellular ceramide level was analyzed and was normalized to the control level (lane 1). Cellular ceramide level in curcumin (25 μM, 24 h)‐treated CaOV3 with SphK1 RNAi or scramble RNAi is shown in (B). Effects of fumonisin B1 (F‐B1, 25 μM) on curcumin (25 μM)+SKI‐II (5 μM) (Cur+SKI‐II)‐induced cell death (48 h) and apoptosis (32 h) are shown in (C) and (D), respectively. *P < 0.05.

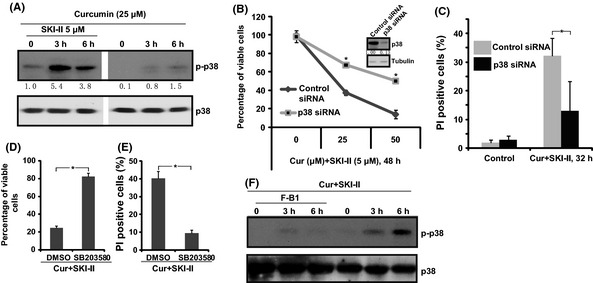

SKI‐II facilitates curcumin‐induced p38 activation to mediate ovarian cancer cell death and apoptosis

Consistent with previous findings,4, 24, 25 we also found moderate p38 activation after curcumin (25 μM) treatment in CaOV3 cells (Fig. 6A), and co‐administration with SKI‐II (5 μM) largely increased p38 activation (Fig. 6A). Importantly, p38 inhibition, either by target siRNA knockdown (Fig. 6B,C) or by pharmacological inhibitor SB 203580 (10 μM, Fig. 6D,E), inhibited curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration‐induced CaOV3 cell death and apoptosis, suggesting that activation of p38 is important for the process (Fig. 6B–E). Fumonisin B1 (25 μM) significantly inhibited p38 activation by curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration, indicating that ceramide production might be the upstream signal for p38 activation (Fig. 6F).

Figure 6.

SKI‐II facilitates curcumin‐induced p38 activation to mediate ovarian cancer cell death and apoptosis. CaOV3 ovarian cancer cells were either left untreated or exposed to curcumin (25 μM) with or without SKI‐II (5 μM) for 3 and 6 h. Total and phosphorylation levels of p38 were analyzed by western blot (A). CaOV3 ovarian cancer cells were transfected with scramble siRNA (control siRNA, 400 nM) or p38 siRNA (400 nM) for 48 h; p38 expression level was examined by western blot (B). Curcumin (25 μM) + SKI‐II (5 μM) induced CaOV3 cell death and apoptosis were analyzed in (B) and (C), respectively. The effect of p38 inhibitor SB 203580 (10 μM, 1 h pretreatment) on curcumin (25 μM) + SKI‐II (5 μM) induced CaOV3 cell death and apoptosis are shown in (D,E). The effect of fumonisin B1 (F‐B1, 25 μM, 1 h pretreatment) on curcumin (25 μM)+SKI‐II (5 μM) (Cur+SKI‐II)‐induced p38 activation was analyzed (F). *P < 0.05.

Dominant negative form of p38 inhibits curcumin and SKI‐II‐induced cytotoxicity

To further confirm the role of p38 in cancer cell cytotoxicity by curcumin and SKI‐II, a dominant negative form of p38 (FLAG tagged) was introduced to CaOV3 cells (Fig. 7A). Results in Figure 7B show that p38 mutation inhibited curcumin and/or SKI‐II‐induced cell death, further supporting the involvement of p38 activation in regulating CaOV3 cell death by curcumin and SKI‐II.

Figure 7.

Dominant negative form of p38 inhibits curcumin and SKI‐II‐induced cytotoxicity. CaOV3 were transfected with vector or FLAG‐taqqed dominant negative form of p38 (DN‐p38, 2 μg/mL, 48 h). Stable cell lines were selected by hydromycin. Expression of p38, FLAG‐p38 and tubulin were analyzed (A). Vector or dominant negative p38 (DN‐p38) transfected CaOV3 cells were treated with curcumin (25 μM) or with SKI‐II (5 μM). Survival cell percentage is shown in (B) *P < 0.05.

SKI‐II facilitates curcumin induced‐Akt inhibition

The fact that p38 inhibition inhibited, but did not reverse, curcumin and SKI‐II‐induced CaOV3 cell death suggests that other mechanisms may also be involved. Western blot results in Figure 8A show that curcumin (25 μM) only slightly reduced Akt activation in CaOV3 cells; co‐administration with SKI‐II (5 μM) caused significant Akt inhibition (Fig. 8A). Fumonisin B1 (25 μM) almost reversed Akt inhibition by curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration (Fig. 8B), suggesting that ceramide production is important for Akt inactivation. We introduced a constitutively active form of Akt (CA‐Akt) to CaOV3 cells, CA‐Akt restored Akt activation after curcumin and SKI‐II treatment, further, CA‐Akt inhibited SKI‐II plus curcumin‐induced anti‐CaOV3 cells effect. These results suggest that Akt inhibition is important for CaOV3 cell death by curcumin and SKI‐II (Fig. 8C–E).

Figure 8.

SKI‐II facilitates curcumin induced‐Akt inhibition. CaOV3 cells were either left untreated (control) or exposed to curcumin (25 μM) with or without SKI‐II (5 μM) for 24 h. Total and phosphorylation levels of Akt were analyzed (A). Effect of fumonisin B1 (F‐B1, 25 μM, 1 h pretreatment) on curcumin (25 μM) plus SKI‐II (5 μM) (Cur+SKI‐II)‐induced Akt activation (24 h) was analyzed (B). Vector or constitutively active Akt (CA‐Akt)‐transfected CaOV3 cells (C) were treated with curcumin (25 μM) or with SKI‐II (5 μM). The percentage of viable cells and PI stained cells are shown in (D) and (E). (F) The proposed signaling pathway. SKI‐II inhibits SphK1 activity to facilitate ceramide production by curcumin. Increased ceramides activate p38 and inhibit Akt activation to mediate ovarian cancer cell apoptosis and growth inhibition. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In the present paper, we propose that SphK1 might be a key potential oncogene for ovarian cancer, and that it is expressed in clinical ovarian tumor tissues and in cultured ovarian cancer cells. SphK1 inhibition, either by siRNA knockdown or through pharmacological inhibitor SKI‐II, inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth and facilitates curcumin‐induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis, which are associated with profound p38 activation and Akt inhibition (see Fig. 8F).

Recent published studies confirm that curcumin induces ceramide production to mediate cancer cell apoptosis.8, 10 Furthermore, exogenously added short‐chain ceramides (C6) sensitize curcumin‐induced melanoma cell death and apoptosis in vitro.11 1‐Phenyl‐2‐decanoylamino‐3‐morpholino‐1‐propanol (PDMP), a well‐known inhibitor of sphingolipid metabolism,26 facilitates curcumin‐induced ceramide production and tumor cell apoptosis.10 Here, we found that SphK1 inhibition by siRNA knockdown or by the pharmacological inhibitor SKI‐II facilitated curcumin‐induced ceramide production and cancer cell apoptosis, while inhibition of ceramides by fumonisin B1 diminished curcumin and SKI‐II's anti‐ovarian cancer effect in vitro.

Activation of p38 is as an important mediator of cell apoptosis in curcumin‐treated cancer cells;4, 24, 27, 28 however, the upstream signaling molecule has not been studied extensively. We found that SKI‐II, which facilitated curcumin‐induced ceramide production, also enhanced p38 activation, whereas the ceramide inhibitor fumonisin B1 largely inhibited curcumin or curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration‐induced p38 activation, suggesting that ceramides might be the key upstream signal for the activation of pro‐apoptotic p38 pathway in curcumin treated cells. As a matter of fact, several published studies have established that activation of p38 is critical for ceramide‐induced cell apoptosis,29, 30, 31 that ceramides cause apoptosis signal‐regulating kinase 1‐regulated p38 activation, and that pharmacologic or siRNA‐mediated inhibition of p38 reduces ceramide‐induced apoptosis.32 However, how exactly curcumin increases ceramide production to activate p38 requires further investigation.

Curcumin has been shown to effectively inhibit Akt/mTOR signaling in a number of cancer cells, but the mechanism remains unclear.3, 4, 33 Recent studies suggest that the phosphatase‐dependent mechanism might be responsible for Akt inhibition by curcumin.33 Previous studies, including ours,21 have indentified ceramide‐activated protein phosphatase (CAPP) as ceramide regulated enzymes. CAPP includes serine/threonine phosphatases 2A (PP2A)34, 35, 36 and protein phophatase‐1 (PP1).37 Increased levels of ceramide activates PP1 and PP2A, which de‐phosphorylate their target proteins, including Akt.34, 35, 36 Here, we found that SKI‐II facilitates curcumin‐induced ceramide production. The fact that inhibition of ceramide production by fumonisin B1 reversed curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration‐induced Akt inhibition suggests that activation of CAPP by ceramides might be responsible for Akt dephosphorylation after curcumin or curcumin and SKI‐II co‐administration treatment. The detailed mechanism, however, requires further investigation.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (810701297, 81101188, 30671894, 30972822 and 30801016), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD 2010–2013), the Health Promotion Project of Jiangsu Province (XK200719, XK200731, RC2007065 and RC2011071), and the Science & Technology Development Foundation of Nanjing Medical University (2010NJMUZ19), the People's Republic of China.

References

- 1. Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as “Curecumin”: from kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol 2008; 75: 787–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharma RA, Gescher AJ, Steward WP. Curcumin: the story so far. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41: 1955–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shi M, Cai Q, Yao L, Mao Y, Ming Y, Ouyang G. Antiproliferation and apoptosis induced by curcumin in human ovarian cancer cells. Cell Biol Int 2006; 30: 221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weir NM, Selvendiran K, Kutala VK et al Curcumin induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis in cisplatin‐resistant human ovarian cancer cells by modulating Akt and p38 MAPK. Cancer Biol Ther 2007; 6: 178–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin YG, Kunnumakkara AB, Nair A et al Curcumin inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in ovarian carcinoma by targeting the nuclear factor‐kappaB pathway. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 3423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bar‐Sela G, Epelbaum R, Schaffer M. Curcumin as an anti‐cancer agent: review of the gap between basic and clinical applications. Curr Med Chem 2010; 17: 190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garcea G, Jones DJ, Singh R et al Detection of curcumin and its metabolites in hepatic tissue and portal blood of patients following oral administration. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 1011–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moussavi M, Assi K, Gomez‐Munoz A, Salh B. Curcumin mediates ceramide generation via the de novo pathway in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2006; 27: 1636–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hilchie AL, Furlong SJ, Sutton K et al Curcumin‐induced apoptosis in PC3 prostate carcinoma cells is caspase‐independent and involves cellular ceramide accumulation and damage to mitochondria. Nutr Cancer 2010; 62: 379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu T, Li J, Qiu Y, Sun H. 1‐Phenyl‐2‐decanoylamino‐3‐morpholino‐1‐propanol (PDMP) facilitates curcumin‐induced melanoma cell apoptosis by enhancing ceramide accumulation, JNK activation, and inhibiting PI3K/AKT activation. Mol Cell Biochem 2012; 361: 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu T, Li J, Sun H. C6 ceramide potentiates curcumin‐induced cell death and apoptosis in melanoma cell lines in vitro. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010; 66: 999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogretmen B, Hannun YA. Biologically active sphingolipids in cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 604–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shida D, Takabe K, Kapitonov D, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting SphK1 as a new strategy against cancer. Curr Drug Targets 2008; 9: 662–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fuereder T, Hoeflmayer D, Jaeger‐Lansky A et al Sphingosine kinase 1 is a relevant molecular target in gastric cancer. Anticancer Drugs 2011; 22: 245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guan H, Liu L, Cai J et al Sphingosine kinase 1 is overexpressed and promotes proliferation in human thyroid cancer. Mol Endocrinol 2011; 25: 1858–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu G, Zheng H, Zhang Z et al Overexpression of sphingosine kinase 1 is associated with salivary gland carcinoma progression and might be a novel predictive marker for adjuvant therapy. BMC Cancer 2010; 10: 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madhunapantula SV, Hengst J, Gowda R, Fox TE, Yun JK, Robertson GP. Targeting sphingosine kinase‐1 to inhibit melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2012; 25: 259–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Scolan E, Pchejetski D, Banno Y et al Overexpression of sphingosine kinase 1 is an oncogenic event in erythroleukemic progression. Blood 2005; 106: 1808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ji C, Cao C, Lu S et al Curcumin attenuates EGF‐induced AQP3 up‐regulation and cell migration in human ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008; 62: 857–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ji C, Yang B, Yang YL et al Exogenous cell‐permeable C6 ceramide sensitizes multiple cancer cell lines to Doxorubicin‐induced apoptosis by promoting AMPK activation and mTORC1 inhibition. Oncogene 2010; 29: 6557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu QY, Wang Z, Ji C et al C6‐ceramide synergistically potentiates the anti‐tumor effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors via AKT dephosphorylation and alpha‐tubulin hyperacetylation both in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis 2011; 2: e117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ji C, Yang YL, He L et al Increasing ceramides sensitizes genistein‐induced melanoma cell apoptosis and growth inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012; 421: 462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Merrill AH Jr, van Echten G, Wang E, Sandhoff K. Fumonisin B1 inhibits sphingosine (sphinganine) N‐acyltransferase and de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in cultured neurons in situ. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 27299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu M, Du Q, Vancurova I et al Proapoptotic effect of curcumin on human neutrophils: activation of the p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 2571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balogun E, Hoque M, Gong P et al Curcumin activates the haem oxygenase‐1 gene via regulation of Nrf2 and the antioxidant‐responsive element. Biochem J 2003; 371: 887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shukla A, Radin NS. Metabolism of D‐[3H]threo‐1‐phenyl‐2‐decanoylamino‐3‐morpholino‐1‐propanol, an inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthesis, and the synergistic action of an inhibitor of microsomal monooxygenase. J Lipid Res 1991; 32: 713–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watson JL, Greenshields A, Hill R et al Curcumin‐induced apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells is p53‐independent and involves p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase activation and downregulation of Bcl‐2 and survivin expression and Akt signaling. Mol Carcinog 2010; 49: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Duvoix A, Blasius R, Delhalle S et al Chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of curcumin. Cancer Lett 2005; 223: 181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen CL, Lin CF, Chang WT, Huang WC, Teng CF, Lin YS. Ceramide induces p38 MAPK and JNK activation through a mechanism involving a thioredoxin‐interacting protein‐mediated pathway. Blood 2008; 111: 4365–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Willaime S, Vanhoutte P, Caboche J, Lemaigre‐Dubreuil Y, Mariani J, Brugg B. Ceramide‐induced apoptosis in cortical neurons is mediated by an increase in p38 phosphorylation and not by the decrease in ERK phosphorylation. Eur J Neurosci 2001; 13: 2037–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brenner B, Koppenhoefer U, Weinstock C, Linderkamp O, Lang F, Gulbins E. Fas‐ or ceramide‐induced apoptosis is mediated by a Rac1‐regulated activation of Jun N‐terminal kinase/p38 kinases and GADD153. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 22173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L et al Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor‐ PSD‐95 protein interactions. Science 2002; 298: 846–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yu S, Shen G, Khor TO, Kim JH, Kong AN. Curcumin inhibits Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling through protein phosphatase‐dependent mechanism. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7: 2609–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dobrowsky RT, Kamibayashi C, Mumby MC, Hannun YA. Ceramide activates heterotrimeric protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 15523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Law B, Rossie S. The dimeric and catalytic subunit forms of protein phosphatase 2A from rat brain are stimulated by C2‐ceramide. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 12808–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolff RA, Dobrowsky RT, Bielawska A, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Role of ceramide‐activated protein phosphatase in ceramide‐mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem 1994; 269: 19605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kishikawa K, Chalfant CE, Perry DK, Bielawska A, Hannun YA. Phosphatidic acid is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 and an inhibitor of ceramide‐mediated responses. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 21335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]