Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that PRMT5, a protein arginine methyltransferase, is involved in tumorigenesis. However, no systematic research has demonstrated the cell‐transforming activity of PRMT5. We investigated the involvement of PRMT5 in tumor formation. First, we showed that PRMT5 was associated with many human cancers, through statistical analysis of microarray data in the NCBI GEO database. Overexpression of ectopic PRMT5 per se or its specific shRNA enhanced or reduced cell growth under conditions of normal or low concentrations of serum, low cell density, and poor cell attachment. A stable clone that expressed exogenous PRMT5 formed tumors in nude mice, which demonstrated that PRMT5 is a potential oncoprotein. PRMT5 accelerated cell cycle progression through G1 phase and modulated regulators of G1; for example, it upregulated cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) 4, CDK6, and cyclins D1, D2 and E1, and inactivated retinoblastoma protein (Rb). Moreover, PRMT5 activated phosphoinositide 3‐kinase (PI3K)/AKT and suppressed c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK)/c‐Jun signaling cascades. However, only inhibition of PI3K activity, and not overexpression of JNK, blocked PRMT5‐induced cell proliferation. Further analysis of PRMT5 expression in 64 samples of human lung cancer tissues by microarray and western blot analysis revealed a tight association of PRMT5 with lung cancer. Knockdown of PRMT5 retarded cell growth of lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1299. In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, we have characterized the cell‐transforming activity of PRMT5 and delineated its underlying mechanisms for the first time.

Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) was cloned during a search for proteins that interacted with the chloride channel protein pICln or with Janus kinase.1, 2 PRMT5 acts as a protein arginine methyltransferase2, 3, 4 and catalyzes the transfer of two methyl groups symmetrically to the arginine residue of protein substrates. PRMT5 is involved in a variety of biological processes, such as the regulation of gene expression through various mechanisms that include histone modification,5, 6, 7 chromatin remodeling,8 mRNA splicing,9, 10, 11 and protein biosynthesis.12 PRMT5 also functions in DNA replication and repair,13 formation of the Golgi apparatus14 and ribosomes,15, 16 cell cycle checkpoints,17 cell migration,18 cell reprogramming,19, 20 development,21, 22 liver metabolism,23 and the circadian clock.24, 25

Several lines of evidence suggest that PRMT5 contributes to tumorigenesis. For instance, PRMT5 is upregulated in mantle cell lymphoma,26, 27 gastric cancer,28 and germ cell tumors.29 PRMT5 is required for cell proliferation26 and cell cycle progression,30 stimulates anchorage‐independent growth,31 mediates cyclin‐D1‐induced neoplastic growth,32 regulates autoactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),33 inhibits apoptosis,34, 35 and represses tumor suppressor genes.26, 27, 31, 36 High levels of PRMT5 expression are correlated with a poor prognosis for breast cancer.37 In contrast, it has also been noted that some activities of PRMT5 are detrimental to the development of cancer.38, 39 Although an increasing amount of data suggest the involvement of PRMT5 in tumorigenesis, the role of PRMT5 in cell transformation remains largely unclear.

To elucidate the contribution of PRMT5 to cell transformation, we investigated: (i) the association of PRMT5 with human cancer; (ii) the cell‐transforming activities of PRMT5; and (iii) the molecular mechanisms by which PRMT5 accelerates progression through the cell cycle and supports cell growth.

Materials and Methods

Chemical, reagents, and plasmids

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), DMEM, penicillin, streptomycin, and Lipofectamine were purchased from Gibco‐BRL (Bethesda, MD, USA). The antibody against β‐actin, polyhema (poly[2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate]), propidium iodide, Giemsa solution, and MTT were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The antibodies against importin β1, HA, GFP, actin, and PRMT5, secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, and luminol reagent were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The antibodies against the phosphoinositide 3‐kinase (PI3K)/AKT and MAPK pathways, various cyclins, and cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDKs) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Secondary antibodies against mouse or rabbit IgG conjugated with HRP were from PerkinElmer–Cetus (Norwalk, CT, USA). Nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl phosphate (BCIP) were from Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA, USA). The expression vectors, such as pEGFP and pcDNA3.1 with an HA tag, were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Aurora‐A siRNA was from Ambion (Austin, TX, USA). pSUPER‐Aurora‐A and pSUPER‐HURP had been prepared by us previously.40 The shRNA for PRMT5 (TRCN 107086) was obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility located at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica, supported by the National Core Facility Program for Biotechnology Grants of National Science Council (NSC) (NSC 100‐2319‐B‐001‐002). The GFP‐PRMT5 MD mutant was a gift from Dr Shilai Bao (Key Laboratory of Molecular and Developmental Biology, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing).14

Tissue procurement and microarray analysis

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Taichung and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. No patient had previously received any neoadjuvant treatment such as chemotherapy before surgery. All patients gave informed consent and signed the consent form individually. The study samples were obtained after surgery from a non‐necrotic area of the tumor and from adjacent non‐tumorous tissue from neighboring sites outside the tumor. Both tumor and adjacent non‐tumor tissues were confirmed by pathologists (Table S1). The tissue samples were placed immediately in cryovials, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis by microarray and western blotting. The microarray data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible through GEO accession number GSE27262 (currently private). Statistically significant differences in PRMT5 between the pairwise tissue samples were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. All analyses were carried out using the SPSS version 13.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA).

Cell cultures, transfection and RNA interference

The 293T cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, and grown in DMEM that contained 5% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Downregulation of PRMT5 was achieved by RNA interference using a vector‐based small hairpin RNA (shRNA) with the sequence ccgggcccagtttgagatgccttatctcgagATAAGGCATCTCAAACTGGGCtttttg where upper case letters indicate siRNA sequence. Retroviral constructs were transfected into GP293 packaging cells, and viral supernatant isolated 48 h after transfection. Infection of target cells was carried out in the presence of 10 μg/mL polybrene.

Preparation of cell extracts and Western blotting

To prepare cell‐free extracts, cells were lysed in extraction buffer, which consisted of 50% lysate buffer (20 mM PIPES pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, 10% sucrose, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 10 μg/mL each of leupeptin, aprotinin, chymostatin, and pepstatin) and 50% IP washing buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 0.1% Triton X‐100, and 40 mM β‐glycerol phosphate). After incubation at 4°C for 30 min, cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 16 100g for 90 min in an Eppendorf centrifuge. The protein concentration was assayed using the Bradford assay (Bio‐Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). Aliquots of the cell extracts were loaded onto a 10% SDS‐polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk in PBST (0.1% Tween‐20 in PBS). Antibodies were incubated with the membranes at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed with PBST at room temperature for 30 min three times. Secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase or HRP were added for 1 h at room temperature and then the membranes were washed three times with PBST for 30 min. NBT and BCIP or luminol reagent were added to develop the signal on the membranes.

MTT‐based cell proliferation assay

Cells seeded in 96‐well plates with 5% or 0.5% FBS were incubated with 100 μL of 2 mg/mL MTT solution at 37°C for 3 h. Subsequently, the medium was removed and 100 μL of DMSO were added for 5 min to extract the purple‐colored product that is generated by living cells. The end product was quantified with a spectrophotometer (Model 680; BioRad, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Data were normalized against the value of OD570 that was obtained on day 1 of culture for each stable clonal cell line.

Flow cytometry

Cells (106) were washed with PBS and fixed in cold methanol. The cells were then incubated with 100 μg/mL RNase at 37°C for 30 min, stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/mL), and analyzed on a FACScan flowcytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle was analyzed using Cell‐FIT software (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instruments Systems, Sparks, MD, USA).

Focus formation assay

Cells (2 × 103) were seeded in 10‐cm dishes and cultured for 10 days. Cell foci were fixed with methanol and stained with 5% Giemsa solution. The number of foci was then counted.

Polyhema‐based anchorage‐independent growth

Polyhema (2.5 mg/mL) was added to 6‐cm dishes and heated on a hotplate until most of the solution had evaporated. The coated dishes were sterilized with UV irradiation before use. Cells (5 × 105) were then seeded onto the dishes and allowed to attach and proliferate for 2 days. The cells were trypsinized and counted with a hemocytometer.

Tumor formation assay

Twelve BALB/C nude mice were divided randomly into four groups of three mice each. The four groups were injected with a clonal cell line that expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) ± Matrigel or a clonal cell line that expressed EGFP‐PRMT5 ± Matrigel. Suspensions of 107 cells in PBS (100 μL) were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of 5‐week‐old male BALB/C nude mice at day 0. The mice were monitored for 4 (Matrigel groups) or 11 (no Matrigel groups) successive weeks and the dimensions of the resultant tumors were measured weekly with calipers. The tumor volume was calculated as length × width × height. At 4 weeks after injection for the Matrigel groups or 11 weeks for the no‐Matrigel groups, all the mice were killed and the subcutaneous tumors or those that grew in secondary regions were removed, measured, and photographed.

In vitro kinase assay for the activities of CDKs

Various CDKs isolated by immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies were incubated with the recombinant GST‐tagged Histone‐H1 or Rb in the kinase buffer containing 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 and 20 mM MgCl2, 100 μM ATP and [γ‐32P]‐ATP (1 mCi/mL) (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of SDS sample buffer and heating at 95°C for 10 min prior to SDS‐PAGE.

Results

PRMT5 possesses cell‐transforming activity

To establish whether PRMT5 is involved in human cancer, we screened the expression of PRMT5 on a genome‐wide scale in cancer tissues using the NCBI GEO database, and found significant upregulation of PRMT5 (P ≤ 0.05) in lung, gastric, and bladder cancer (Table 1). Expression of PRMT5 was also higher in metastatic colon cancer than in primary cancer tissues.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of the differential upregulation of PRMT5 in various primary and metastatic cancers using NCBI GEO datasets

| Disease | Probeset of PRMT5 | Variable | Sample number | P‐value | GSE Acc# | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | 217786_at | Normal | 5 | 0.004* | GSE3268 | 44 |

| Disease | 5 | |||||

| Gastric cancer | AF015913_at | Normal | 8 | 0.001* | GSE2685 | 45 |

| Disease | 22 | |||||

| Bladder cancer | 217786_at | Normal | 9 | 0.000* | GSE3167 | 46 |

| Transitional cell carcinoma with CIS | 13 | |||||

| Bladder cancer | 217786_at | Normal | 9 | 0.000* | GSE3167 | 46 |

| Transitional cell carcinoma without CIS | 15 | |||||

| Colon | 217786_at | Primary | 3 | 0.006* | GSE1323 | 47 |

| Metastatic | 3 |

*Indicates the static significance of PRMT5 expression level between normal and cancerous tissues.

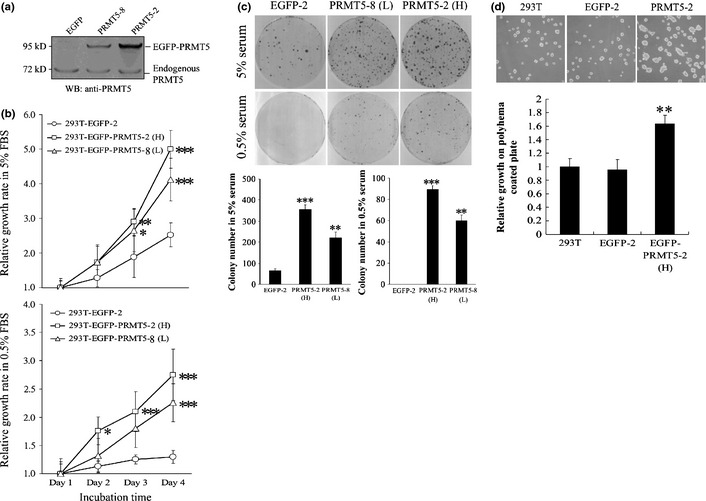

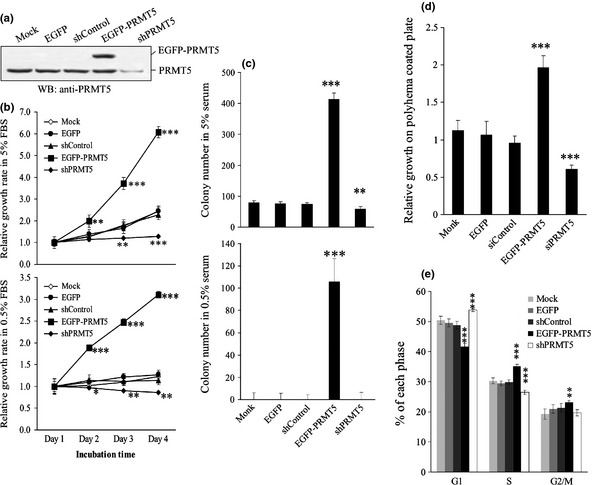

The association of upregulation of PRMT5 with human cancer prompted us to investigate the potential cell‐transforming activities of PRMT5. Stable clonal cell lines that expressed EGFP‐PRMT5 were established in 293T cells. The two stable cell lines both expressed a higher level of exogenous PRMT5 than endogenous PRMT5, although the level of PRMT5 expression was higher in clone 2 than clone 8 (Fig. 1a). A cell line that expressed EGFP was used as a control. The PRMT5 clonal cell lines grew much faster in 5% serum than the cell line that expressed EGFP (Fig. 1b). The PRMT5 clones also grew in the presence of low levels of serum (0.5%), unlike the EGFP clone. Moreover, PRMT5 stimulated the formation of foci of transformed cells in 5% serum (Fig. 1c), and even in 0.5% serum, in which the level of growth factors was extremely low and no cell foci were induced by EGFP. Finally, PRMT5 promoted anchorage‐independent cell growth, using a polyhema‐based assay (Fig. 1d). On the contrary, knockdown of PRMT5 by its specific shRNA but not scrambled control reduced cell growth in media containing normal or low serum, in polyhema‐coated plates, and trapped cells in G1 (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

PRMT5 induces cell proliferation at low serum concentrations and under anchorage‐independent conditions. (a) Stable 293T clonal cell lines that expressed EGFP or EGFP‐PRMT5 at higher (clone 2, H) or lower levels of expression (clone 8, L) were subjected to western blotting with an antibody against PRMT5. (b) Clonal cell lines that expressed EGFP or PRMT5 were subjected to the MTT assay in 5% (upper) or 0.5% (lower) serum for 1–4 days. (c) Clonal cell lines that expressed EGFP or PRMT5 were subjected to a cell foci formation assay in 5% or 0.5% serum. Cell foci were fixed and stained with Giemsa solution. The number of foci were counted and plotted. (d) Clonal cell lines that expressed EGFP or PRMT5 were subjected to a polyhema‐based anchorage‐independent growth assay. The cells were allowed to grow for 2 days on polyhema plates and subsequently were trypsinized and counted with a hemocytometer. The number of cells in each group at day 2 was normalized against the number of cells that were seeded originally (i.e. 5 × 105). *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance by Student's t‐test with P < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively.

Figure 2.

The effects of PRMT5 shRNA on cell growth in 293T cells. (a) 293T cells harboring nothing (Mock), EGFP, EGFP‐PRMT5, PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled shRNA were applied to Western blot adopting anti‐PRMT5 antibody. (b) 293T cells harboring nothing, EGFP, EGFP‐PRMT5, PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled shRNA were applied to MTT‐based cell growth assay in 5% or 0.5% serum for 1–4 days. (c) 293T cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were applied to focus formation assay in 10% or 0.5% serum. (d) 293T cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were subjected to polyhema‐based anchorage‐independent growth assay. (e) 293T cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were analyzed by flowcytometer. The percentage cells residing in each specific phase were calculated and plotted. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance by Student's t‐test with P < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively.

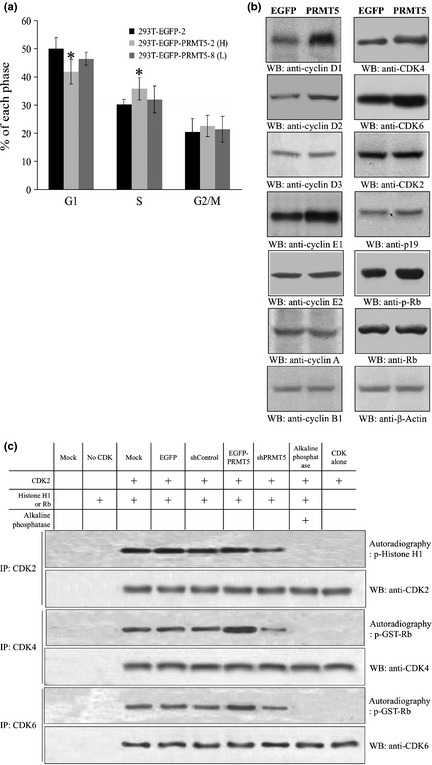

PRMT5 modulates regulators of G1 phase

The rapid cell growth that was detected in Figure 1 suggested that PRMT5 might regulate cell cycle progression. This was confirmed by flow cytometry, which showed that the proportion of cells in the G1 phase was significantly lower in the two PRMT5 clones than in the EGFP clone. In addition, clone 2 had a shorter G1 phase than clone 8 (Fig. 3a), which agreed with the finding that clone 2 grew faster than clone 8, and EGFP clone was the slowest one. To investigate further how PRMT5 accelerated the G1 phase, we examined regulators of the cell cycle in PRMT5 clone 2 and the EGFP clone by western blotting. Interestingly, the protein level of positive regulators of G1, such as cyclin D1, cyclin D2, cyclin E1, CDK4, and CDK6, was increased in the PRMT5 clone, whereas negative regulators of G1 phase, such as retinoblastoma (Rb) protein, were inhibited through protein phosphorylation (Fig. 3b). Consistently, the activities of CDK4 and CDK6, but not CDK2, were increased in PRMT5 cells and decreased in PRMT5 shRNA cells (Fig. 3c). Regulators of S and G2/M, such as cyclin A and cyclin B1, were unaffected in the PRMT5 and EGFP clones, which suggested that PRMT5 exerts a specific regulatory effect on G1 phase.

Figure 3.

PRMT5 accelerates progression through G1 and upregulates regulators of G1 phase. (a) The EGFP and PRMT5 clonal cell lines were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the percentage of cells in each specific phase was calculated and plotted. (b) The protein level of various cell cycle regulators in the EGFP and PRMT5 clonal cell lines was analyzed by western blotting. Antibodies against cyclins A, B1, D1–D3, E1, and E2; CDK2, 4, and 6; p19; Rb protein; phospho‐Rb protein; and β‐actin were used for western blotting. (c) The kinase activities of various CDKs were assayed by performing in vitro kinase reaction where CDK2, CDK4 or CDK6 was isolated by immunoprecipitation employing specific antibodies from cells harboring nothing, EGFP empty vector, EGFP‐PRMT5, PRMT5 shRNA, or scrambled shRNA. Recombinant Histone H1 or Rb was used as substrate and incubated with CDKs in kinase reaction buffer in the presence of [γ‐P 32]‐ATP. *Statistical significance by Student's t‐test with P < 0.05.

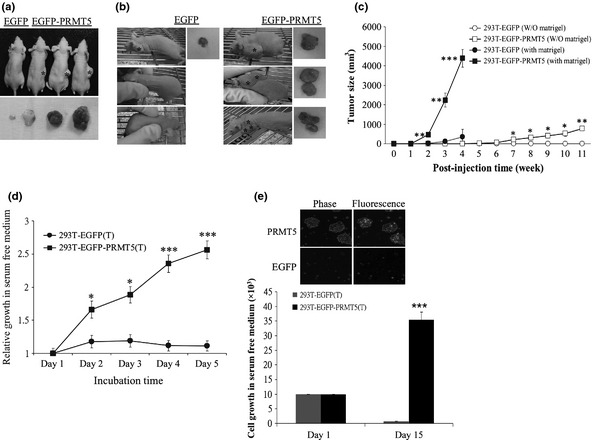

The PRMT5 clone induces tumors in nude mice

As mentioned above, overexpression of PRMT5 enhanced the growth of cultured cells. It was of importance to investigate whether PRMT5 stimulated cell growth in animals. The EGFP clone or the EGFP‐PRMT5 clone (clone 2) was injected into nude mice in the absence (Fig. 4a) or presence (Fig. 4b) of Matrigel, and the size of the resultant tumors was measured every week for 11 (without Matrigel) or 4 (with Matrigel) successive weeks (Fig. 4c). The PRMT5 clone formed tumors regardless of whether Matrigel was present, although Matrigel accelerated tumor formation. Surprisingly, the PRMT5 tumor cells that were isolated from nude mice continued to proliferate in serum‐free medium for 5 days (Fig. 4d). After 5 days, the PRMT5 tumor cells became detached from the Petri dish, and survived and even proliferated for 15 days, whereas the EGFP tumor cells did not proliferate (Fig. 4e).

Figure 4.

PRMT5 induces tumor formation in nude mice. (a–c) PRMT5 clonal cells formed tumors in nude mice. EGFP clonal cells or EGFP‐PRMT5 (clone 2) clonal cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice in the absence (a) or presence (b) of Matrigel. Tumor size was measured weekly (c). (d,e) Cells from the PRMT5‐induced tumor grew in the absence of serum. PRMT5‐induced tumor cells taken from nude mice were subjected to the MTT assay (d) or counted with a hemocytometer (e) in serum‐free medium. *, **, and *** represent statistical significance by Student's t‐test with P < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively.

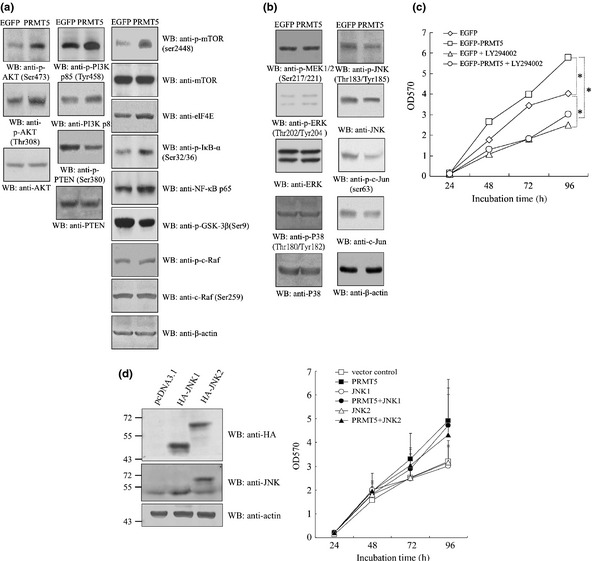

PRMT5 activates the PI3K/AKT survival pathway

The survival and cell growth in serum‐free medium suggested that survival pathways had been activated in the PRMT5 tumor cells. Western blotting showed that the level of phosphorylation at serine 308 or serine 473 of AKT was increased in the PRMT5 clones. Analysis of the upstream regulators of AKT revealed that phosphorylation of PI3K p85 was also increased in the PRMT5 clones. Consistently, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is a negative regulator of AKT, was inactivated due to a decrease in phospho‐PTEN in the PRMT5 clones. The PRMT5‐activated AKT signal was transmitted via mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/elF4E, inhibitor of κB (IκB)‐α/nuclear factor (NF)‐κB p65, and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)‐3β, rather than through c‐Raf (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

PRMT5 activates AKT but suppresses JNK signaling cascades. EGFP and PRMT5 clonal cells were subjected to western blotting using antibodies against (a) AKT signaling molecules, including phospho‐ and total PI3K p85, PI3K p110, phospho‐PDK1, phospho‐ and total PTEN, phospho‐ and total AKT, mTOR, phospho‐mTOR, elF4E, phospho‐IκB‐α, NF‐κB p65, phospho‐GSK‐3β, c‐Raf, phospho‐c‐Raf and β‐actin, and (b) MAPK signaling factors including phospho‐MEK1/2, phospho‐ and total ERK, phospho‐ and total p38, phospho‐ and total JNK, phospho‐ and total c‐Jun, and β‐actin. (c) An inhibitor of PI3K suppressed the growth of PRMT5 clonal cells. EGFP and PRMT5 clonal cells were subjected to the MTT‐based cell proliferation assay in the absence or presence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 1–4 days. (d) Overexpression of JNK1 or JNK2 did not alter the rate of cell proliferation induced by PRMT5. EGFP and PRMT5 clonal cells transfected with HA‐JNK1 or HA‐JNK2 were subjected to Western blot adopting anti‐HA, ‐pan JNK or ‐actin antibody, or the MTT assay for 1–4 days. *Statistical significance by Student's t‐test with P < 0.05.

We also examined the MAPK signaling cascades. The level of active ERK or p38 remained unchanged in PRMT5 clones. However, the JNK pathway was suppressed (Fig. 5b).

To understand further whether upregulation or downregulation of PI3K or JNK was essential for PRMT5‐dependent cell growth, the effect of inactivation of PI3K (Fig. 5c) or overexpression of ectopic JNK1/2 (Fig. 5d) on the growth of the PRMT5 clone was investigated. Intriguingly, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 blocked the stimulation of cell growth by PRMT5. In contrast, overexpression of JNK1 or JNK2 did not significantly inhibit the growth of the PRMT5 clone. The results indicated that PI3K, and not JNK, plays a major role in mediating PRMT5‐induced cell growth.

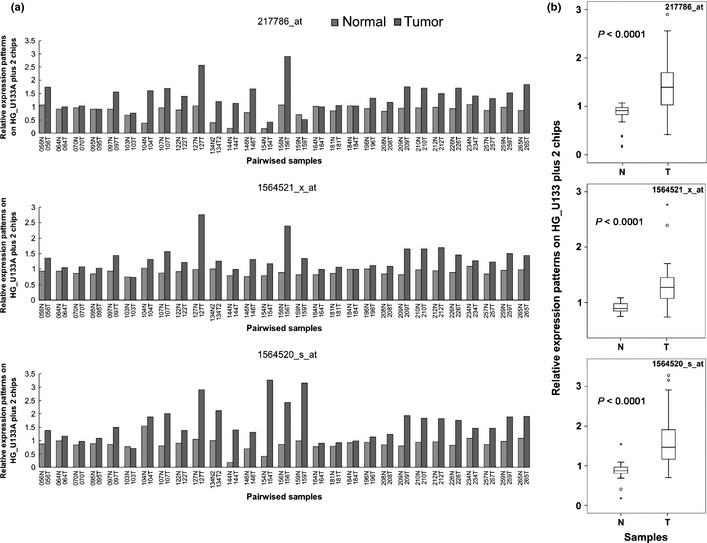

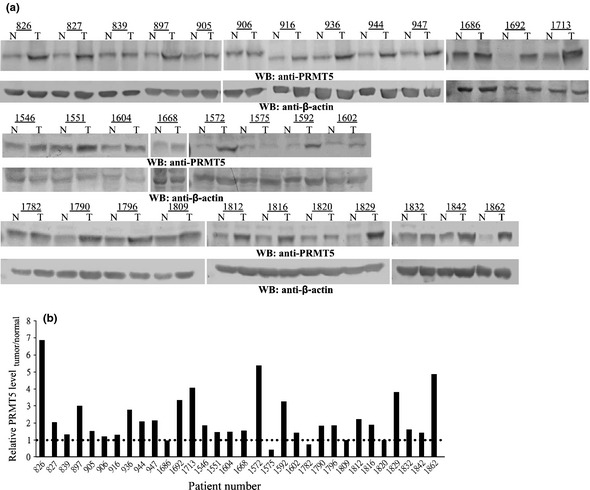

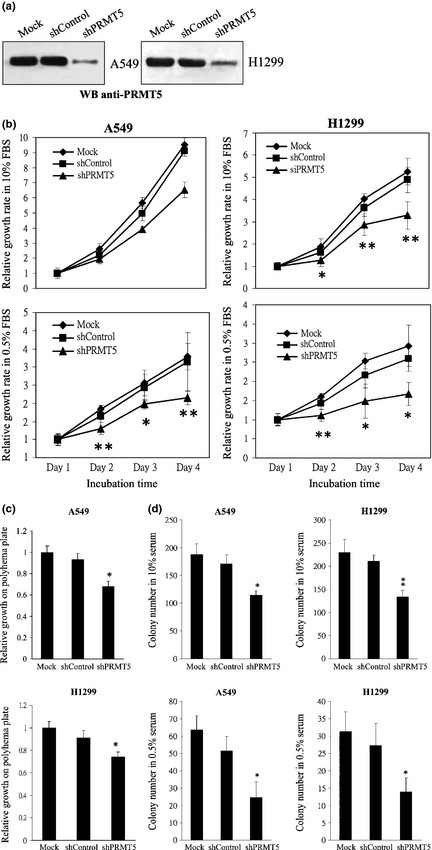

PRMT5 is upregulated in the majority of human lung cancer tissues

On the basis of our analyses, PRMT5 induced cell growth in medium with a low concentration of serum or even in serum‐free medium, under conditions of poor cell attachment, and in nude mice. Moreover, PRMT5 upregulated regulators of G1 and activated the PI3K/AKT signaling cascade. All these findings reveal a strong cell‐transforming activity of PRMT5, and predict a high prevalence of overexpression of PRMT5 in cancer tissues. Our statistical analysis of the NCBI GEO database revealed that PRMT5 was upregulated in human cancer, including lung cancer. Consequently, we performed microarray analysis with three different probes that detected PRMT5 transcripts using 29 pairs of samples of cancerous and adjacent normal tissues from patients with lung cancer. The microarray data were normalized by quantile normalization using the Robust Multichip Average to produce expression signals for the transcripts that were based on corresponding pairs of oligonucleotide probes. Figure 6(a) shows that the level of the PRMT5 transcript was increased in most of the samples from patients with lung cancer, regardless of which probe was used. Furthermore, the distribution of data in the grouping classification indicated a significant difference statistically (P < 0.0001) between tumor and normal tissues from the same patient (Fig. 6b). Subsequently, we examined the expression of PRMT5 protein in another collection of 32 samples of lung cancer tissue by western blotting with an antibody against PRMT5 (Fig. 7). Similarly, the level of PRMT5 protein was increased in 15 out of 32 of the samples and was twofold higher in cancerous tissues than in adjacent normal tissues. Moreover, knockdown of PRMT5 in lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1299 retarded cell proliferation, inhibited anchorage‐independent cell growth and reduced focus formation (Fig 8), revealing the cell transforming activity of PRMT5 in lung cancers.

Figure 6.

PRMT5 is overexpressed in patients with lung cancer. (a) The level of PRMT5 mRNA in samples from 29 patients with lung cancer was determined by microarray analysis. Overexpression of PRMT5 was observed in all three probesets (217786_at, 1564521_x_at, and 1564520_s_at). The numbers on the X axis represent the codes of the patients. (b) Box plot shows the distribution of data in grouping classification and a statistically significant difference (P < 0.0001) between tumor tissues and adjacent non‐tumor tissues from the same lung cancer patients. T, tumor tissue; N, adjacent non‐tumor tissue.

Figure 7.

Protein expression of PRMT5 in 32 samples of lung cancer tissue. (a) Biopsies from paired lung tumor (T) and adjacent normal tissues (N) were subjected to western blotting using an antibody against PRMT5 or actin. The numbers on the X axis represent the codes of the patients. Actin served as a loading control. (b) The levels of PRMT5 and actin were quantified by densitometry. The level of PRMT5 protein in each paired tissue was normalized against that of actin. The ratio of normalized PRMT5 in the tumor to that in normal tissue was calculated and plotted.

Figure 8.

Effects of PRMT5 shRNA on the cell growth of A549 and H1299 cells. (a) A549 cells or H1299 cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were applied to Western blot adopting anti‐PRMT5 antibody. (b) A549 or H1299 cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were applied to MTT‐based cell growth assay in 10% or 0.5% serum for 1–4 days. (c) A549 or H1299 cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were subjected to polyhema‐based anchorage‐independent growth assay. (d) A549 or H1299 cells harboring PRMT5 shRNA or scrambled control were applied to focus formation assay in 10% or 0.5% serum. * and ** represent statistical significance by Student's t‐test with P < 0.05 and 0.01 respectively.

Discussion

There is increasing evidence to show that PRMT5 is involved in tumorigenesis. However, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate the cell‐transforming activity of PRMT5, and the ability of PRMT5 to induce cell growth under conditions of normal or low concentrations of serum, low cell density, and poor cell attachment. The cell line that expressed ectopic PRMT5 survived and grew in nude mice. Moreover, PRMT5 activated PI3K/AKT signaling and G1 cyclins/CDKs to survive in extreme conditions or to stimulate cell growth.

PRMT5 is essential for progression through G1 because knockdown of PRMT5 has been shown previously to arrest cell growth in G1 phase,30 and, in the present study, overexpression of PRMT5 accelerated G1 progression. A recent study has reported that PRMT5 is activated by CDK4/cyclin D1 through phosphorylation of the PRMT5‐interacting protein MEP50.32 Activation of PRMT5 leads to methylation and stabilization of the replication‐licensing protein CDT1,32 upregulation of which induces a more rapid entry into S phase.41 The results of the present study demonstrated that PRMT5 upregulates cyclin D1, cyclin D2, CDK4, and CDK6, which are regulators of early G1, as well as cyclin E1, which regulates late G1. This indicates that PRMT5 accelerates progression through G1 by upregulating G1 cyclins and CDKs, and also reveals that PRMT5 might act upstream of CDK4/cyclin D1.

PRMT5 activated AKT by inducing hyperphosphorylation of the upstream positive regulator PI3K and hypophosphorylation of the negative regulator PTEN. The AKT signal activated the downstream targets mTOR/eIF4E and inactivated GSK‐3β. eIF4E is a positive regulator42 and GSK‐3β a negative regulator43 of the level of cyclin D, which explains the increase in cyclin D protein that was induced by PRMT5. In addition, PRMT5 regulated MAPK signaling by selectively suppressing JNK, rather than ERK or p38. However, overexpression of JNK1/2 reduced cell growth of the PRMT5 clone only slightly, whereas inactivation of PI3K significantly blocked cell proliferation of the PRMT5 clone, which indicated that PI3K plays a major role in mediating PRMT5‐dependent cell growth.

A PRMT5 mutant that had lost methyltransferase activity could not induce anchorage‐independent growth (Fig. S1a), which suggested that the cell‐transforming activity of PRMT5 is relayed through downstream substrates. However, the results of the present study showed that PRMT5 interfered with the phosphorylation of several cellular factors, which suggested that the methylation of proteins by PRMT5 might affect protein phosphorylation. Overexpression of PRMT5 caused global changes in protein phosphorylation in cells (Fig. S1b), which further suggested the ability of PRMT5 to modulate protein phosphorylation. As a consequence, it is likely that elucidating the contribution of crosstalk between protein methylation and phosphorylation to cell transformation will become one of the main challenges in cancer biology.

By statistical analysis of the NCBI GEO database, we showed that the level of the PRMT5 transcript was increased in many human cancers, including lung cancer. This upregulation was supported further by microarray analysis and western blotting, which showed that PRMT5 mRNA or protein was elevated in tissue samples from 64 patients with cancer. Consistently, the DNA region covering the PRMT5 locus (14q11.2 according to NCBI) in human cancer also reveals amplification of 14q11.2 in many cancer tissues (Table S2). In addition, we found that PRMT5 was upregulated significantly in metastatic colon cancer as compared with primary cancer, which suggested that PRMT5 regulates cell migration. This is supported by the observation that PRMT5 is involved in the control of cell migration through methylation of EGFR.33 However, it has also been reported that PRMT5 regulates cell attachment via methylation of the membrane protein srGAP2.13 To clarify the effect of PRMT5 on cell migration, PRMT5 was overexpressed in 293T cells for a wound healing assay. PRMT5 was found not to exert a significant effect on cell migration compared to EGFP cells (Fig. S2), which implied that, overall, PRMT5 does not significantly influence cell migration.

In summary, we present evidence to show the association of PRMT5 with lung cancer, and to demonstrate that PRMT5 possesses cell‐transforming and tumorigenic activities. Further analyses revealed that these activities can be explained by the ability of PRMT5 to accelerate progression through G1, upregulate G1 cyclins/CDKs, suppress Rb protein, and activate AKT signaling cascades. Hence, Elucidation of the involvement of PRMT5 in the cell cycle provides the possibility of a new approach to fighting cancer by targeting the functions of this protein.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. PRMT5 methyltransferase dead mutant cannot induce anchorage‐independent growth, and PRMT5 affects protein phosphorylation. Fig. S2. PRMT5 did not induce migration of 293T cells. Table S1. The diagnostic information of lung cancer patients. Table S2. The PRMT5 locus is amplified in human cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technical supports provided by Core Facilities for High Throughput Experimental Analysis of Institute of Systems Biology and Bioinformatics, College of Science, National Central University (supported by the Aim of Top University Project from the Ministry of Education), and Li‐Wen Lee and Jen Miao in Taichung Veterans General Hospital. The work was supported by the National Science Council (NSC 99‐2112‐M‐008‐012, NSC 100‐2314‐B‐075‐004‐MY2, NSC 100‐2314‐B‐075‐004‐MY2), Taichung Veterans General Hospital/National Chi Nan University Joint Research Program (TCVGH‐NCNU1017903), and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V100C‐160).

(Cancer Sci, 2012; 103: 1640–1650)

References

- 1. Krapivinsky G, Pu W, Wickman K, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. pICln binds to a mammalian homolog of a yeast protein involved in regulation of cell morphology. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 10811–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pollack BP, Kotenko SV, He W, Izotova LS, Barnoski BL, Pestka S. The human homologue of the yeast proteins Skb1 and Hsl7p interacts with Jak kinases and contains protein methyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 31531–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee JH, Cook JR, Pollack BP, Kinzy TG, Norris D, Pestka S. Hsl7p, the yeast homologue of human JBP1, is a protein methyltransferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 274: 105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rho J, Choi S, Seong YR, Cho WK, Kim SH, Im DS. Prmt5, which forms distinct homo‐oligomers, is a member of the protein‐arginine methyltransferase family. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 11393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng Y, Wang J, Asher S et al Histone H4 acetylation differentially modulates arginine methylation by an in Cis mechanism. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 20323–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu X, Hoang S, Mayo MW, Bekiranov S. Application of machine learning methods to histone methylation ChIP‐Seq data reveals H4R3me2 globally represses gene expression. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11: 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao Q, Rank G, Tan YT et al PRMT5‐mediated methylation of histone H4R3 recruits DNMT3A, coupling histone and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16: 304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dacwag CS, Ohkawa Y, Pal S, Sif S, Imbalzano AN. The protein arginine methyltransferase Prmt5 is required for myogenesis because it facilitates ATP‐dependent chromatin remodeling. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27: 384–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chuang TW, Peng PJ, Tarn WY. The exon junction complex component Y14 modulates the activity of the methylosome in biogenesis of spliceosomal small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 8722–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deng X, Gu L, Liu C et al Arginine methylation mediated by the Arabidopsis homolog of PRMT5 is essential for proper pre‐mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 19114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meister G, Fischer U. Assisted RNP assembly: SMN and PRMT5 complexes cooperate in the formation of spliceosomal UsnRNPs. EMBO J 2002; 21: 5853–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jung GA, Shin BS, Jang YS et al Methylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 induced by basic fibroblast growth factor via MAPK. Exp Mol Med 2011; 43: 550–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo Z, Zheng L, Xu H et al Methylation of FEN1 suppresses nearby phosphorylation and facilitates PCNA binding. Nat Chem Biol 2010; 6: 766–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou Z, Sun X, Zou Z et al PRMT5 regulates Golgi apparatus structure through methylation of the golgin GM130. Cell Res 2010; 20: 1023–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Majumder S, Alinari L, Roy S et al Methylation of histone H3 and H4 by PRMT5 regulates ribosomal RNA gene transcription. J Cell Biochem 2010; 1009: 553–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ren J, Wang Y, Liang Y, Zhang Y, Bao S. Xu Z. Methylation of ribosomal protein S10 by protein‐arginine methyltransferase 5 regulates ribosome biogenesis. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 12695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hendrix ND, Wu R, Kuick R, Schwartz DR, Fearon ER, Cho KR. Fibroblast growth factor 9 has oncogenic activity and is a downstream target of Wnt signaling in ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 1354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo S, Bao S, srGAP2 arginine methylation regulates cell migration cell spreading through promoting dimerization. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 35133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nagamatsu G, Kosaka T, Kawasumi M et al A germ cell‐specific gene, Prmt5, works in somatic cell reprogramming. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 10641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tee WW, Pardo M, Theunissen TW et al Prmt5 is essential for early mouse development and acts in the cytoplasm to maintain ES cell pluripotency. Genes Dev 2010; 24: 2772–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim SJ, Yoo BC, Uhm CS, Lee SW. Posttranslational arginine methylation of lamin A/C during myoblast fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1814: 308–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pei Y, Niu L, Lu F et al Mutations in the Type II protein arginine methyltransferase AtPRMT5 result in pleiotropic developmental defects in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiol 2007; 144: 1913–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanamaluru D, Xiao Z, Fang S et al Arginine methylation by PRMT5 at a naturally occurring mutation site is critical for liver metabolic regulation by small heterodimer partner. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31: 1540–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hong S, Song HR, Lutz K, Kerstetter RA, Michael TP, McClung CR. Type II protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) is required for circadian period determination in Arabidopsis thaliana . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 21211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanchez SE, Petrillo E, Beckwith EJ et al A methyl transferase links the circadian clock to the regulation of alternative splicing. Nature 2010; 468: 112–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pal S, Baiocchi RA, Byrd JC, Grever MR, Jacob ST, Sif S. Low levels of miR‐92b/96 induce PRMT5 translation and H3R8/H4R3 methylation in mantle cell lymphoma. EMBO J 2007; 26: 3558–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang L, Pal S, Sif S. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 suppresses the transcription of the RB family of tumor suppressors in leukemia and lymphoma cells. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 6262–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim JM, Sohn HY, Yoon SY et al Identification of gastric cancer‐related genes using a cDNA microarray containing novel expressed sequence tags expressed in gastric cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 473–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eckert D, Biermann K, Nettersheim D et al Expression of BLIMP1/PRMT5 and concurrent histone H2A/H4 arginine 3 dimethylation in fetal germ cells, CIS/IGCNU and germ cell tumors. BMC Dev Biol 2008; 8: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scoumanne A, Zhang J, Chen X. PRMT5 is required for cell‐cycle progression and p53 tumor suppressor function. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37: 4965–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pal S, Vishwanath SN, Erdjument‐Bromage H, Tempst P, Sif S. Human SWI/SNF‐associated PRMT5 methylates histone H3 arginine 8 and negatively regulates expression of ST7 and NM23 tumor suppressor genes. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 9630–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aggarwal P, Vaites LP, Kim JK et al Nuclear cyclin D1/CDK4 kinase regulates CUL4 expression and triggers neoplastic growth via activation of the PRMT5 methyltransferase. Cancer Cell 2010; 18: 329–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsu JM, Chen CT, Chou CK et al Crosstalk between Arg1175 methylation and Tyr1173 phosphorylation negatively modulates EGFR‐mediated ERK activation. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13: 174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanaka H, Hoshikawa Y, Oh‐hara T et al PRMT5, a novel TRAIL receptor‐binding protein, inhibits TRAIL‐induced apoptosis via nuclear factor‐kappaB activation. Mol Cancer Res 2009; 7: 557–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yang M, Sun J, Sun X, Shen Q, Gao Z, Yang C. Caenorhabditis elegans protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT‐5 negatively regulates DNA damage‐induced apoptosis. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tae S, Karkhanis V, Velasco K et al Bromodomain protein 7 interacts with PRMT5 and PRC2, and is involved in transcriptional repression of their target genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39: 5424–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Powers MA, Fay MM, Factor RE, Welm AL, Ullman KS. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 accelerates tumor growth by arginine methylation of the tumor suppressor programmed cell death 4. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 5579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fabbrizio E, El Messaoudi S, Polanowska J et al Negative regulation of transcription by the type II arginine methyltransferase PRMT5. EMBO Rep 2002; 3: 641–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu F, Zhao X, Perna F, Wang L et al JAK2V617F‐mediated phosphorylation of PRMT5 downregulates its methyltransferase activity and promotes myeloproliferation. Cancer Cell 2011; 19: 283–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu CT, Hsu JM, Lee YC, Tsou AP, Chou CK, Huang CY. Phosphorylation and stabilization of HURP by Aurora‐A: implication of HURP as a transforming target of Aurora‐A. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 5789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arentson E, Faloon P, Seo J et al Oncogenic potential of the DNA replication licensing protein CDT1. Oncogene 2002; 21: 1150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosenwald IB, Kaspar R, Rousseau D et al Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E regulates expression of cyclin D1 at transcriptional and post‐transcriptional levels. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 21176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kong DX, Yamori T. ZSTK474, a novel phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase inhibitor identified using the JFCR39 drug discovery system. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2010; 31: 1189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wachi S, Yoneda K, Wu R. Interactome‐transcriptome analysis reveals the high centrality of genes differentially expressed in lung cancer tissues. Bioinformatics 2005; 21: 4205–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hippo Y, Taniguchi H, Tsutsumi S et al Global gene expression analysis of gastric cancer by oligonucleotide microarrays. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dyrskjøt L, Kruhøffer M, Thykjaer T et al Gene expression in the urinary bladder: a common carcinoma in situ gene expression signature exists disregarding histopathological classification. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 4040–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Provenzani A, Fronza R, Loreni F, Pascale A, Amadio M, Quattrone A. Global alterations in mRNA polysomal recruitment in a cell model of colorectal cancer progression to metastasis. Carcinogenesis 2006; 27: 1323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. PRMT5 methyltransferase dead mutant cannot induce anchorage‐independent growth, and PRMT5 affects protein phosphorylation. Fig. S2. PRMT5 did not induce migration of 293T cells. Table S1. The diagnostic information of lung cancer patients. Table S2. The PRMT5 locus is amplified in human cancer.