Abstract

Cell growth demands new protein synthesis, which requires nucleolar ribosomal functions. Ribosome biogenesis consumes a large proportion of the cell's resources and energy, and so is tightly regulated through an intricate signaling network to guarantee fidelity. Thus, events that impair ribosome biogenesis cause nucleolar stress. In response to this stress, several nucleolar ribosomal proteins (RPs) translocate to the nucleoplasm and bind to MDM2. MDM2‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation of the tumor suppressor p53 is then blocked, resulting in p53 accumulation and the induction of p53‐dependent cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Nucleolar stress is therefore a quality control surveillance mechanism that monitors the synthesis and assembly of the rRNA and protein components of ribosomes. Although nucleolar stress signaling pathways have been extensively analyzed, critical questions remain about their regulatory mechanisms. For example, how do RPs translocate from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm to exert their functions, and do these p53‐regulating RPs influence the prognosis of human cancer patients? Our laboratory recently identified the nucleolar protein PICT1 as a novel regulator of nucleolar stress. PICT1 sequesters the ribosomal protein RPL11 in the nucleolus, preventing it from binding to MDM2. MDM2 is then free to degrade p53, favoring tumor cell growth. Accordingly, the level of PICT1 in a tumor is becoming a useful prognostic marker for human cancers. This review summarizes the evidence that links nucleolar stress to tumorigenesis, and casts PICT1 as an oncogenic player in human cancer biology. (Cancer Sci 2012; 103: 632–637)

Regulation of p53 in Response to Nucleolar Stress

p53 and Mdm2/Hdm2.

In response to cellular stress, the tumor suppressor p53 induces cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, DNA repair, or senescence. Inactivating mutations in the Tp53 gene encoding p53 thus contribute to tumorigenesis. p53 also functions in processes required for development, metabolism, stem cell renewal, and microRNA processing.1, 2 Therefore, the tight control of p53 levels is crucial for normal homeostasis. p53 regulation depends largely on the activity of Mdm2/Hdm2 (murine double minute 2; HDM2, human ortholog), an E3 ubiquitin ligase that polyubiquitinates the p53 protein and facilitates its proteasomal degradation.3 Thus, inhibition of Mdm2/Hdm2 leads to p53 stabilization and accumulation. At the genetic level, Tp53 deficiency completely rescues the lethal phenotype of Mdm2 knockout mice, confirming that the main physiological function of MDM2 is to control p53.4

Cellular stresses that activate the Mdm2/Hdm2‐p53 pathway also induce signaling responsible for its regulation, including cascades involving ATM‐Chk2 and ATR‐Chk1. In response to DNA damage (DNA stress), these checkpoint kinases phosphorylate Mdm2/Hdm2 and p53 such that their interaction is abrogated,5, 6 allowing p53 to arrest the cell until the damage is repaired. P53‐Mdm2/Hdm2 binding is also inhibited by interaction with p19Arf (p14Arf in humans), which is triggered by infection or the activation of oncogenes such as RAS or c‐myc (oncogenic stress).7, 8 Indeed, p14Arf is often mutated or silenced in human tumor cells. In addition, stresses that stimulate post‐translational modifications of p53 and Mdm2/Hdm2, such as ubiquitination, sumoylation, acetylation and/or phosphorylation, can also influence p53 activation.6

Nucleolar functions.

The nucleolus is the site of rRNA transcription, rRNA processing, and the assembly of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits. Because nucleolar functions consume large amounts of cellular energy and resources, they are highly regulated in a manner that ensures proper cell growth.9 During cell division, the nucleoli disassemble and later reform around the rDNA genes known as nucleolar organizing regions. The rDNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase I (PolI), and the resulting transcripts are processed to generate the 28S, 18S, and 5.8S rRNAs. Within the nucleolus, these rRNAs are assembled with ribosomal proteins (RPs) to form the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, which are exported into the cytoplasm and assembled into the 80S ribosome that carries out protein synthesis.9

Nucleolar stress.

Most types of cellular stress that result in increased p53 stability also disrupt nucleolar integrity, suggesting that the nucleolus may be a central hub for stress sensors.10 However, impaired ribosome biogenesis generates nucleolar stress that activates p53 without disrupting nucleolar integrity.11, 12 Thus, nucleolar disruption per se does not explain why p53 is activated by nucleolar stress. A clue may lie in the fact that the p53‐Mdm2/Hdm2 pathway is also regulated by free RPs. In response to nucleolar stress, the ribosomal components RPL11, RPL5, RPL23, and RPS7 are released from the nucleolus into the nucleoplasm where they associate with Mdm2/Hdm2, inhibiting its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity toward p53 and thus promoting p53 stabilization and activation.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 In addition, RPL26, which is ubiquitinated by MDM2, binds to the 5′‐UTR of p53 mRNA and increases its translation in response to DNA damage.18 Lastly, RPS3 interacts directly with p53 and protects it from Mdm2/Hdm2‐mediated ubiquitination induced by oxidative stress.19 Thus, both nucleolar and ribosome biogenesis‐related proteins are very important regulators in the nucleolar stress signaling cascade leading to p53 activation (Fig. 1).10, 20

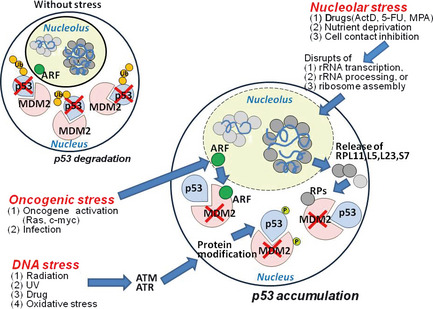

Figure 1.

Stress pathways leading to MDM2 inactivation and p53 accumulation. In a cell without stress, ribosomal proteins (RPs) and ARF are confined to the nucleolus, and MDM2 is active in the nucleus and facilitates the eventual degradation of p53 protein. In response to oncogenic stress, ARF binds to MDM2 and inhibits its E3 ligase activity, blocking p53 ubiquitination and eventual degradation. Similarly, in response to DNA stress, the checkpoint kinases ATM and ATR phosphorylate p53 and MDM2, blocking their interaction and promoting p53 accumulation. In response to stimuli causing nucleolar stress, nucleolar RPs such as RPL11, L5, L23, and S7 are released from nucleolus. These RPs translocate into the nucleoplasm and bind to MDM2, preventing p53 degradation. All three stress pathways result in p53 accumulation and activation that induces cell cycle arrest/apoptosis.

What is the physiological purpose of nucleolar stress? It may halt cell cycle progression until sufficient functional ribosomes are present, or may induce the p53‐mediated apoptosis/senescence of cells that cannot produce appropriate ribosomes. Thus, nucleolar stress can be considered a form of quality control surveillance that monitors the synthesis and assembly of rRNAs and RPs, much as DNA stress functions as a quality control surveillance mechanism for DNA damage. Multiple RPs may be required to scrutinize the various steps of nucleolar stress signaling, or to compensate for another RP's failure, so that the fidelity of ribosome biogenesis is ensured.20 Experimentally, the release of specific RPs from the nucleoli characteristic of nucleolar stress can be induced either by chemicals that disrupt ribosome biogenesis or by ablation of the genes involved in this process. However, aside from nutrient deprivation and cell contact inhibition,21 the mechanisms that cause nucleolar stress in vivo are undefined.

Mechanisms Triggering Nucleolar Stress

Inhibition of rRNA synthesis.

Inhibition of rRNA synthesis is a major mechanism of nucleolar stress induction. Such inhibition is caused by chemotherapeutic drugs that inhibit PolI or deplete nucleotide pools necessary for rRNA synthesis. Low concentrations of actinomycin D (ActD), which intercalates into rDNA and inhibits PolI‐mediated rRNA transcription, induces nucleolar stress and activates p53.15, 21 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) is metabolized into fluorouridine triphosphate that is misincorporated into RNA and blocks rRNA synthesis and processing. Similarly, mycophenolic acid (MPA) inhibits inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, depleting the guanine nucleotide pool and disrupting rRNA synthesis. Both 5‐FU and MPA enhance the association of RPL5 and RPL11 with Mdm2/Hdm2, thereby triggering nucleolar stress and p53 activation.22, 23

The importance of p53 activation induced by PolI inhibition has been highlighted by studies of mice and human cells deficient for either TIF‐IA, a transcription factor essential for PolI‐directed activity,24 or DHX33, a cell cycle‐regulated nucleolar protein that interacts with the PolI transcription factor UBF.25 In addition, zebrafish expressing mutated BAP28, a component of the U3 snoRNA‐containing RNP complex important for rDNA transcription/processing, exhibit nucleolar stress and p53 activation.26 Inhibited rRNA synthesis also results following DNA damage,27 hypoxia,28 viral infection,29 mTOR inactivation by nutrient deprivation or mTOR inhibitors,30 or epigenetic regulation of rRNA transcription.31 Inhibition of new rRNA synthesis in turn impairs ribosome assembly, triggering the release of free RPs that may be the drivers of the nucleolar stress signaling cascade.

Impaired rRNA processing.

Defects of rRNA processing may also induce nucleolar stress. The ablation of genes encoding rRNA processing factors or the expression of dominant‐negative forms of these factors can both activate p53. For example, expression of a dominant‐negative form of either the nucleolar protein Bop1, which is involved in 28S and 5.8S rRNA formation,32 or WDR12, a WD40 repeat protein that binds to the Pes1‐Bop1 complex essential for rRNA processing,33 causes nucleolar stress and p53 activation. Another nucleolar protein involved in rRNA processing and implicated in nucleolar stress responses is nucleophosmin (NPM)/B23. Under stress, NPM translocates to the nucleoplasm and promotes the interaction of p14Arf with Mdm2/Hdm2, thereby stabilizing p53.34, 35 Failure to activate the p14Arf‐NPM‐p53 pathway occurs in many human cancers, including AML, and NPM is often mutated in AML cells.36 Deficiency of murine Rbm19, an rRNA processing protein, elevates p53 activity and impairs early embryogenesis.37 Similarly, deficiency of the zebrafish rRNA processing protein Wrd36 activates p53.38 The rRNA processing molecules nucleolin.39 and nucleostemin also stabilize p53 by binding directly to MDM2. Interestingly, RNAi‐mediated knockdown of nucleostemin enhances the interaction of RPL5 and RPL11 with MDM2, promoting p53 activation.40 These findings imply that, without adequate processed rRNA to bind to newly synthesized RPs, these RPs may be free to leave the nucleolus and interact with Mdm2/Hdm2, stabilizing p53.20

Imbalance of RP proteins.

An imbalance in RP concentrations may also induce nucleolar stress. A decreased level of any RP, regardless of its role in p53 regulation, induces p53 accumulation (reviewed by Chakraborty et al.)41 In mouse models, RPL22 deficiency induces p53 upregulation that selectively arrests the development of αβ T cells.42 Mice bearing mutations of RPS19 or RPS20 display reduced body size and excessive pigmentation due to p53‐dependent Kit ligand expression.43 Mice with a T cell‐ or oocyte‐specific deficiency of RPS6 exhibit impaired T cell development44 or perigastrulation lethality,45 respectively. In the latter two cases, the RP‐deficient cells show p53 upregulation.

In RPS6‐deficient cells, p53 activation is associated with increased translation of RPL11 mRNA, even without nucleolar disruption.12 Thus, RPL11, which influences MDM2 function, may be a key factor controlling p53 accumulation. Importantly, neddylation of RPL11 by NEDD8 is required for RPL11 stabilization and nucleolar localization, and nucleolar stress can disrupt neddylation. Therefore, an increase in the non‐neddylated form of RPL11 during nucleolar stress may allow RPL11 to translocate to the nucleoplasm and interact with MDM2.46

Although a decreased RP level usually increases p53 accumulation, overexpression of some RPs induces p53 upregulation, and a reduction in or functional inactivation of some RPs can prevent p53 accumulation. For example, mice lacking RPL11 exhibit embryonic lethality due to excessive p53‐mediated apoptosis,47 but RNAi‐mediated deletion of RPL11, RPL5, RPS7, or RPS3,15, 19, 21 prevents p53 accumulation during drug‐induced nucleolar stress. Consistent with this observation, mice expressing MDM2 that cannot bind to RPL11 or RPL5 fail to activate p53 during nucleolar stress. Moreover, when these mutants were crossed with Eμ‐c‐Myc transgenic mice, the progeny developed more frequent lymphomas at an earlier time than parental Eμ‐c‐Myc mice.48 Finally, RPS29 overexpression in rat thymocytes or human HeLa cells induces p53‐mediated apoptosis.49 Collectively, these results show that RP imbalances can modulate p53 levels either up or down, depending on the specific molecule, mutation and/or cell type involved.

Nucleolar Stress and Human Disease

Diamond–Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a well‐studied human ribosomopathy characterized by erythroid aplasia due to congenital bone marrow failure. DBA patients usually present in infancy with a range of abnormalities, including craniofacial and cardiac defects. Although 25% of DBA patients carry a mutation in RPS19,50 mutations in RPL5, RPS10, RPL11, RPL35A, RPS26, RPS24, RPS7 and RPS17 have also been documented.51 Although the anemia induced by RPS19 mutation has been partly attributed to p53 accumulation,52 DBA patients are also predisposed to hematopoietic malignancies.

Another common human ribosomopathy “5q− myelodysplastic syndrome” is a preleukemic disease caused either by haploinsufficiency for RPS14 or by deletion of miR‐145 or miR146a. Patients exhibit macrocytic anemia, erythroid dysplasia, and mono‐lobulated megakaryocytes, apparently due to a progenitor cell defect associated with impaired p53 activation.53, 54, 55

Several other ribosomopathies that are quite rare have also been described. ‘X‐linked dyskeratosis congenita' is a rare ribosomopathy characterized by premature aging, skin abnormalities, bone marrow failure, and increased cancer risk. This disease is caused by mutations in the dyskeratosis congenita 1 (DKC1) gene encoding dyskerin, a pseudouridine synthase. Cells of these patients exhibit impaired rRNA processing and decreased telomerase activity.56 ‘Treacher Collins syndrome’, an autosomal dominant disorder of p53‐dependent craniofacial development, is caused by loss‐of‐function mutations in the Treacher Collins–Franceschetti syndrome 1 (TCOF1) gene, which is essential for the methylation and synthesis of rRNA.57 ‘Cartilage‐hair hypoplasia' is an autosomal recessive disorder featuring short‐limbed skeletal dysplasia, sparse hair, impaired immunity and erythropoiesis, and cancer predisposition. This disease is due to mutations in the RMRP gene that encodes an RNase important for rRNA processing.58 Autosomal recessive ‘Shwachman–Diamond syndrome' is characterized by bone marrow failure, leukemia predisposition, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, skeletal abnormalities and stunted growth. A mutation in the Shwachman–Bodian–Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene impairs the joining of ribosomal subunits and causes this disorder.59

The above work establishes that human RP defects are associated with increased cancer risk, but the types and frequencies of these malignancies vary greatly. Precisely how alterations of the nucleolar stress pathway contribute to cancer onset is unknown. It may be that loss of an RP either increases the amount/function of an oncogenic protein such as c‐myc.60, or decreases the amount/function of a tumor suppressor such as p53.61 These matters remain under investigation.

PICT1 as a New Pivotal Regulator of Nucleolar Stress

Until recently, a major unresolved issue in the field of nucleolar stress was the regulation controlling how and when RPs translocate from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm. What specialized mechanism prevents RP–MDM2 interaction under normal conditions? There is now evidence indicating that the status of the genes involved in this mechanism can affect p53 function and thus influence the prognosis of human cancer patients.

PICT1 as a RP regulator.

Our laboratory has discovered that the nucleolar protein PICT1 (protein interacting with the C terminus‐1) is a key regulator of nucleolar stress. PICT1 binds to RPL11 in the nucleolus and prevents it from interacting with MDM2, thus blocking p53 accumulation and activation.62 This finding arose from our analyses of PICT1‐deficient mice. To circumvent the early embryonic lethality of PICT1 null mice, we generated PICT1 −/− mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells that lacked endogenous PICT1 expression but expressed exogenous PICT1 in a doxycycline (Dox)‐regulatable manner such that PICT1 expression was turned “on” in the absence of Dox but turned off by Dox treatment. Studies of these cells revealed an inverse relationship between PICT1 expression and p53 accumulation (Fig. 2), in that PICT1‐deficient ES cells rapidly died in culture due to p53‐dependent apoptosis. Parallel p53‐dependent effects were observed in vivo in thymocytes of mice with conditional PICT1 inactivation, as well as in vitro in cultured cancer cell lines.62

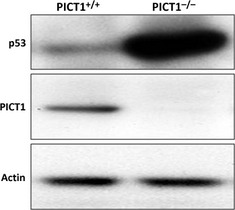

Figure 2.

PICT1 regulates p53 protein level. Immunoblot detecting p53 and Pict1 proteins in embryonic stem (ES) cells (PICT1tetTg+/PICT1Δ/−), which were left untreated (PICT1+/+) or treated with Dox (PICT1−/−) for 2 days.

After ruling out mechanisms known to induce p53 accumulation, including DNA damage, increased p19ARF, and decreased PTEN, we used mass spectrometry to define the molecular mechanism by which PICT1 deficiency leads to p53 activation. PICT1 binds to numerous RPs in the nucleolus, including RPL11, and PICT1 deficiency caused RPL11 to re‐distribute from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm (Fig. 3), a behavior exhibited by no other RP.62 Thus, PICT1 is specifically required for the nucleolar anchoring of RPL11. RNAi‐mediated knockdown of RPL11, but no other RP, reduced p53 accumulation in PICT1‐deficient cells, and RPL11 in the nucleoplasm bound to Mdm2/Hdm2, inhibiting its E3 ligase activity. Significantly, PICT1 protein was dramatically decreased during nucleolar stress induced by ActD or MPA.62

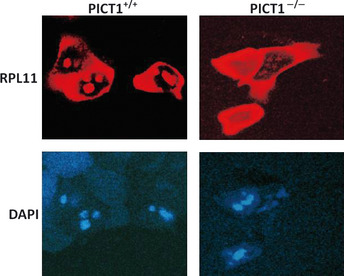

Figure 3.

PICT1 regulates nucleolar stress by sequestering RPL11 in the nucleolus. Embryonic stem (ES) cells (PICT1tetTg+/PICT11Δ/−) were transfected with RPL11‐DsRed. At 16 h post‐transfection, cells were left untreated (PICT1+/+) or treated with Dox (PICT1−/−), and RPL11 protein localization was determined by confocal microscopy. 4′6′‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) was used to counterstain nuclei.

PICT1 as an oncogenic regulator.

The PICT1 gene resides in human chromosome 19q13.32, which is often altered in human glioma and ovarian cancer.63, 64 It was originally reported that LOH in 19q13 correlated with a better prognosis for patients with oligodendrogliomas,65 but a later examination of the RNAi‐mediated knockdown of PICT1 in HeLa cells showed that PICT1 depletion led to PTEN degradation, cell proliferation, and anti‐apoptosis.66 Although this latter study suggested a putative tumor suppressor function for PICT1, subsequent studies have not supported this hypothesis. Humans with colon or esophageal cancers that harbor wild‐type p53 and low PICT1 show a better 5‐year survival rate than patients whose cancers have high PICT1 levels.62 Moreover, the development of chemical carcinogen‐induced skin tumors is delayed in PICT1 +/− mice, which show reduced PICT1 expression.62 These findings indicate that PICT1 is a vital new regulator of nucleolar stress whose deregulation can affect cancer development, particularly where p53 is intact. We believe that PICT1 normally sequesters RPL11 in the nucleolus, promoting the degradation of p53 by Mdm2/Hdm2 (Fig. 4) A lack of PICT1 therefore permits RPL11‐mediated p53 stabilization and activation. Conversely, excessive nucleolar PICT1 might prevent the mounting of an efficient p53 response to oncogenic stress, potentially driving neoplastic changes. It should be noted, however, that PICT1 overexpression in resting cells does not reduce basal p53 levels, implying the involvement of additional factors in stressed cells.

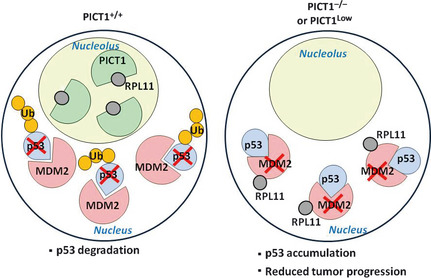

Figure 4.

Regulation of the nucleolar stress pathway via PICT1‐RPL11 binding. Left: When PICT1 is present in the nucleolus, RPL11 is retained in the nucleolus and MDM2 is free to ubquitinate p53, promoting its degradation. Right: When PICT1 is absent from the nucleolus or its expression is reduced, nucleolar RPL11 escapes into the nucleoplasm and binds to MDM2, blocking p53 ubiquitination. p53 accumulation in PICT1‐deficient or PICT1low tumor cells then slows tumor progression.

Remaining Questions

Some important questions remain concerning PICT1's physiological functions:

Can excessive PICT1 actively drive tumorigenesis, and is PICT1 amplified or activated in human tumors?

Are stress‐induced post‐translational modifications, such as neddylation of RPL11, involved in PICT1‐mediated regulation of the nucleolar stress response?

We found that Trp53 deletion could not prevent the embryonic death of PICT1‐null mice. Thus, a p53‐independent role of PICT1 exists but what is its nature?

What mechanism decreases PICT1 protein in response to stress stimuli?

Is PICT1 also involved in p53 accumulation following genotoxic (DNA) stress?

Why does PICT1 deficiency result in the release of only RPL11 into the nucleoplasm, even though PICT1 binds to all Mdm2/Hdm2‐interacting RPs?

Conclusion

This review has attempted to summarize evidence implicating ribosomal proteins, particularly RPL11, as potential tumor suppressors. We have shown that PICT1 is a key regulator of RPL11 and thus a major player in the prevention of nucleolar stress. Excessive PICT1 may therefore be oncogenic, rendering PICT1 level in human cancers a useful prognostic marker. Studies of factors influencing PICT1 expression/stability, and the identification of agents that interfere with PICT1‐RPL11 binding, may lead to new anticancer drugs, especially for Tp53‐intact tumors.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Vousden KH, Ryan KM. p53 and metabolism. Nat Rev 2009; 9: 691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suzuki HI, Yamagata K, Sugimoto K et al Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature 2009; 460: 529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A et al Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature 1997; 387: 296–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Montes de Oca Luna R, Wagner DS, Lozano G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2‐deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature 1995; 378: 203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maya R, Balass M, Kim ST et al ATM‐dependent phosphorylation of Mdm2 on serine 395: role in p53 activation by DNA damage. Genes Dev 2001; 15: 1067–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell 2009; 137: 609–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF‐INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell 1998; 92: 725–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pomerantz J, Schreiber‐Agus N, Liegeois NJ et al The Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, p19Arf, interacts with MDM2 and neutralizes MDM2's inhibition of p53. Cell 1998; 92: 713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perry RP. Balanced production of ribosomal proteins. Gene 2007; 401(1–2): 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rubbi CP, Milner J. Disruption of the nucleolus mediates stabilization of p53 in response to DNA damage and other stresses. EMBO J 2003; 22: 6068–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindstrom MS, Nister M. Silencing of ribosomal protein S9 Elicits a multitude of cellular responses inhibiting the growth of cancer cells subsequent to p53 activation. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fumagalli S, Di Cara A, Neb‐Gulati A et al Absence of nucleolar disruption after impairment of 40S ribosome biogenesis reveals an rpL11‐translation‐dependent mechanism of p53 induction. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11: 501–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lohrum MA, Ludwig RL, Kubbutat MH et al Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell 2003; 3: 577–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Wolf GW, Bhat K et al Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53‐dependent ribosomal‐stress checkpoint pathway. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23: 8902–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dai MS, Lu H. Inhibition of MDM2‐mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation by ribosomal protein L5. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 44475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dai MS, Zeng SX, Jin Y et al Ribosomal protein L23 activates p53 by inhibiting MDM2 function in response to ribosomal perturbation but not to translation inhibition. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 7654–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen D, Zhang Z, Li M et al Ribosomal protein S7 as a novel modulator of p53‐MDM2 interaction: binding to MDM2, stabilization of p53 protein, and activation of p53 function. Oncogene 2007; 26: 5029–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takagi M, Absalon MJ, McLure KG et al Regulation of p53 translation and induction after DNA damage by ribosomal protein L26 and nucleolin. Cell 2005; 123: 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yadavilli S, Mayo LD, Higgins M et al Ribosomal protein S3: a multi‐functional protein that interacts with both p53 and MDM2 through its KH domain. DNA Repair(Amst) 2009; 8: 1215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang Y, Lu H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell 2009; 16: 369–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhat KP, Itahana K, Jin A et al Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition‐induced p53 activation. EMBO J 2004; 23: 2402–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun XX, Dai MS, Lu H. 5‐fluorouracil activation of p53 involves an MDM2‐ribosomal protein interaction. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 8052–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun XX, Dai MS, Lu H. Mycophenolic acid activation of p53 requires ribosomal proteins L5 and L11. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 12387–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan X, Zhou Y, Casanova E et al Genetic inactivation of the transcription factor TIF‐IA leads to nucleolar disruption, cell cycle arrest, and p53‐mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell 2005; 19: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang Y, Forys JT, Miceli AP et al Identification of DHX33 as a mediator of rRNA synthesis and cell growth. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31: 4676–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azuma M, Toyama R, Laver E et al Perturbation of rRNA synthesis in the bap28 mutation leads to apoptosis mediated by p53 in the zebrafish central nervous system. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 13309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kruhlak M, Crouch EE, Orlov M et al The ATM repair pathway inhibits RNA polymerase I transcription in response to chromosome breaks. Nature 2007; 447: 730–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mekhail K, Rivero‐Lopez L, Khacho M et al Restriction of rRNA synthesis by VHL maintains energy equilibrium under hypoxia. Cell Cycle 2006; 5: 2401–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kao CF, Chen SY, Lee YH. Activation of RNA polymerase I transcription by hepatitis C virus core protein. J Biomed Sci 2004; 11: 72–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mayer C, Grummt I. Ribosome biogenesis and cell growth: mTOR coordinates transcription by all three classes of nuclear RNA polymerases. Oncogene 2006; 25: 6384–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murayama A, Ohmori K, Fujimura A et al Epigenetic control of rDNA loci in response to intracellular energy status. Cell 2008; 133: 627–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pestov DG, Strezoska Z, Lau LF. Evidence of p53‐dependent cross‐talk between ribosome biogenesis and the cell cycle: effects of nucleolar protein Bop1 on G(1)/S transition. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21: 4246–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holzel M, Rohrmoser M, Schlee M et al Mammalian WDR12 is a novel member of the Pes1‐Bop1 complex and is required for ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. J Cell Biol 2005; 170: 367–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kurki S, Peltonen K, Latonen L et al Nucleolar protein NPM interacts with HDM2 and protects tumor suppressor protein p53 from HDM2‐mediated degradation. Cancer Cell 2004; 5: 465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Itahana K, Bhat KP, Jin A et al Tumor suppressor ARF degrades B23, a nucleolar protein involved in ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. Mol Cell 2003; 12: 1151–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E et al Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 254–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang J, Tomasini AJ, Mayer AN. RBM19 is essential for preimplantation development in the mouse. BMC Dev Biol 2008; 8: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skarie JM, Link BA. The primary open‐angle glaucoma gene WDR36 functions in ribosomal RNA processing and interacts with the p53 stress‐response pathway. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: 2474–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daniely Y, Dimitrova DD, Borowiec JA. Stress‐dependent nucleolin mobilization mediated by p53‐nucleolin complex formation. Mol Cell Biol 2002; 22: 6014–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dai MS, Sun XX, Lu H. Aberrant expression of nucleostemin activates p53 and induces cell cycle arrest via inhibition of MDM2. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 4365–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chakraborty A, Uechi T, Kenmochi N. Guarding the ‘translation apparatus’: defective ribosome biogenesis and the p53 signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev 2011; 2: 507–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anderson SJ, Lauritsen JP, Hartman MG et al Ablation of ribosomal protein L22 selectively impairs alphabeta T cell development by activation of a p53‐dependent checkpoint. Immunity 2007; 26: 759–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McGowan KA, Li JZ, Park CY et al Ribosomal mutations cause p53‐mediated dark skin and pleiotropic effects. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 963–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sulic S, Panic L, Barkic M et al Inactivation of S6 ribosomal protein gene in T lymphocytes activates a p53‐dependent checkpoint response. Gene Dev 2005; 19: 3070–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Panic L, Tamarut S, Sticker‐Jantscheff M et al Ribosomal protein S6 gene haploinsufficiency is associated with activation of a p53‐dependent checkpoint during gastrulation. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 8880–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sundqvist A, Liu G, Mirsaliotis A et al Regulation of nucleolar signalling to p53 through NEDDylation of L11. EMBO Rep 2009; 10: 1132–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chakraborty A, Uechi T, Higa S et al Loss of ribosomal protein L11 affects zebrafish embryonic development through a p53‐dependent apoptotic response. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Macias E, Jin A, Deisenroth C et al An ARF‐independent c‐MYC‐activated tumor suppression pathway mediated by ribosomal protein‐Mdm2 interaction. Cancer Cell 2010; 18: 231–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Khanna N, Reddy VG, Tuteja N et al Differential gene expression in apoptosis: identification of ribosomal protein S29 as an apoptotic inducer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 277: 476–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Draptchinskaia N, Gustavsson P, Andersson B et al The gene encoding ribosomal protein S19 is mutated in Diamond‐Blackfan anaemia. Nat Genet 1999; 21: 169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gazda HT, Sheen MR, Vlachos A et al Ribosomal protein L5 and L11 mutations are associated with cleft palate and abnormal thumbs in Diamond‐Blackfan anemia patients. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 83: 769–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dutt S, Narla A, Lin K et al Haploinsufficiency for ribosomal protein genes causes selective activation of p53 in human erythroid progenitor cells. Blood 2011; 117: 2567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ebert BL, Pretz J, Bosco J et al Identification of RPS14 as a 5q‐ syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature 2008; 451: 335–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Barlow JL, Drynan LF, Hewett DR et al A p53‐dependent mechanism underlies macrocytic anemia in a mouse model of human 5q‐ syndrome. Nat Med 2010; 16: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Starczynowski DT, Kuchenbauer F, Argiropoulos B et al Identification of miR‐145 and miR‐146a as mediators of the 5q‐ syndrome phenotype. Nat Med 2010; 16: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mochizuki Y, He J, Kulkarni S et al Mouse dyskerin mutations affect accumulation of telomerase RNA and small nucleolar RNA, telomerase activity, and ribosomal RNA processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jones NC, Lynn ML, Gaudenz K et al Prevention of the neurocristopathy Treacher Collins syndrome through inhibition of p53 function. Nat Med 2008; 14: 125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martin AN, Li Y. RNase MRP RNA and human genetic diseases. Cell Res 2007; 17: 219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wong CC, Traynor D, Basse N et al Defective ribosome assembly in Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Blood 2011; 118: 4305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dai MS, Arnold H, Sun XX et al Inhibition of c‐Myc activity by ribosomal protein L11. EMBO J 2007; 26: 3332–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. MacInnes AW, Amsterdam A, Whittaker CA et al Loss of p53 synthesis in zebrafish tumors with ribosomal protein gene mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sasaki M, Kawahara K, Nishio M et al Regulation of the MDM2‐P53 pathway and tumor growth by PICT1 via nucleolar RPL11. Nat Med 2011; 17: 944–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim YJ, Cho YE, Kim YW et al Suppression of putative tumour suppressor gene GLTSCR2 expression in human glioblastomas. J Pathol 2008; 216: 218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Merritt MA, Parsons PG, Newton TR et al Expression profiling identifies genes involved in neoplastic transformation of serous ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2009; 9: 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC et al Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 1473–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Okahara F, Itoh K, Nakagawara A et al Critical role of PICT‐1, a tumor suppressor candidate, in phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5‐trisphosphate signals and tumorigenic transformation. Mol Biol Cell 2006; 17: 4888–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]