Abstract

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is a rare and aggressive variant of endometrial carcinoma. Little is known about the pathological and biological features of this tumor. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and hormone receptor (HR) expression have an important role in tumor behavior and clinical outcome, but their relevance in UPSC is not clear. In the present study, the immunohistochemical expression of HER2 and HR was assessed in 27 patients with Stage I disease, 13 with Stage II disease, 25 with Stage III disease, and 6 with Stage IV disease. Correlations between HER2 and HR expression and the clinicopathological parameters of UPSC were evaluated using Cox's univariate and multivariate analyses. For all patients, the 5‐year recurrence‐free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were 51% and 66%, respectively; in patients with Stage I, II, III and IV disease, the RFS and OS were 67%/81%, 59%/77%, 43%/54% and 0%/0%, respectively. Of all 71 patients, 14% (10/71) were positive for HER2 and 52% (37/71) were positive for HR. Overexpression of HER2 was correlated with lower OS (P = 0.01), whereas HR overexpression was correlated with higher OS (P = 0.008). In multivariate models, HER2, HR, and histologic subtype were identified as independent prognostic indicators for RFS (P = 0.022, P = 0.018, and P = 0.01, respectively), but HR was the only independent factor associated with OS (P = 0.044). Thus, HER2 and HR are prognostic variables in UPSC, with HR an independent prognostic factor for OS. (Cancer Sci 2012; 103: 926–932)

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecological malignancy in the US and its occurrence in Japan has increased recently.1, 2 Endometrial carcinomas are conventionally divided into two subgroups, Types I and II. Type I endometrial carcinomas is associated with a hyperestrogenic state and tends to be well differentiated, whereas Type II endometrial carcinomas is not associated with a hyperestrogenic status and is high grade.3 Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC), initially described by Hendrickson et al.,4 is one of the Type II endometrial carcinomas. It comprises <10% of all endometrial carcinomas, but accounts for over 50% of all recurrences and deaths caused by this disease.5, 6, 7 Despite aggressive treatment, locoregional and distant failures are common, even in patients treated by surgery for early stage disease.5, 8, 9, 10 One study reported a 5‐year overall survival (OS) rate for 129 patients with UPSC of 45.9%, with recurrence even occurring in four of 21 (19%) patients with Stage IA.7 Nonetheless, there is little information regarding the molecular basis for the aggressive biological behavior of UPSC.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) is a well‐established tumor biomarker that is overexpressed in a wide variety of carcinomas, including breast, ovary, prostate, and lung.11, 12 Overexpression of HER2 is a significant factor in aggressive tumor behavior and poor clinical outcome.13

Estrogen and progesterone are important hormones secreted by the ovary that act through specific receptors, namely the estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptors. The expression of ER and PR is important in endometrial cancers, especially in low‐grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma,14, 15, 16, 17 but the relevance of ER and PR expression in UPSC is not known.

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of HER2, ER, and PR status in a large cohort of UPSC patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients and tissue samples

The present study was performed in 71 patients with UPSC (mean age 63.6 years; range 47–81 years). Patients with serous adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix were excluded from the study. No patient was lost to follow‐up. All subjects initially underwent surgery in the Gynecology Division of the National Cancer Center Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) between 1997 and 2008. All patients underwent hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy, and pelvic lymph node evaluation. Staging was according to the 1988 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO, http://www.figo.org/files/figo-corp/docs/staging_booklet.pdf, accessed 01 Jul 2011) surgical staging system. Following primary surgical treatment, asymptomatic patients underwent pelvic examination, Pap smear, ultrasound, and serial determination of tumor markers (carbohydrate antigen [CA] 125, CA19‐9 and carcinoembryonic antigen) every 2–6 months. Symptomatic patients underwent the appropriate examinations, as indicated, including chest radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

For the present study, all surgically removed pathology samples were reviewed by two gynecological pathologists. Postoperative classification was according to the 2002 revision of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM classification of malignant tumors.18 Based on World Health Organization classification,19 at least 10% of the tumor area had to have serous papillary features for inclusion in the present study. Cases were identified as pure UPSC if the serous component occupied all of the tumor area. Otherwise, cases were identified as mixed UPSC. Of the 71 patients included in the present study, 50 were determined to have pure‐type UPSC, whereas 21 had mixed‐type UPSC. The clinicopathological factors examined included patient age, histologic subtype of UPSC (pure or mixed), FIGO stage, myometrial invasion, lymph node status, and lymph‐vascular space involvement (LVSI).

Immunohistochemistry

After being formalin fixed and embedded in paraffin, all tumor tissue specimens were cut into 4‐μm serial sections for immunohistochemical staining, in addition to the usual H&E staining. The present study was performed with the approval of the Internal Review Board (Division of Gynecology, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan) on Ethical Issues. The antibodies and test kits used for immunohistochemistry were as follows: the Hercep Test (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), anti‐ER mouse monoclonal antibody (Clone 1D5; Dako), and anti‐PR mouse monoclonal antibody (Clone PgR636; Dako). An autoimmunostainer (Autostainer Link 48; Dako) was used for immunohistochemical staining of HER2/neu, ER, and PR.

Scoring of the results

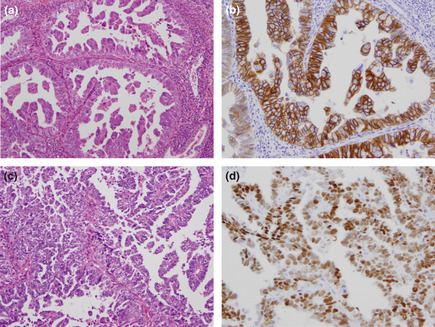

The results of the immunohistochemical staining were evaluated as the percentage of positively stained neoplastic cells. In mixed‐type tumors, only the serous component was evaluated. Immunoreactivity for HER2 was scored semiquantitatively as follows: 0, no immunostaining or membrane staining in <10% of cells; 1+, weak or barely perceptible staining in >10% of cells, with the cells stained in only part of the membrane; 2+, weak or moderate staining in the whole membrane in >10% of tumor cells; and 3+, strong staining in the whole membrane in >10% of tumor cells. Scores of 2+ and 3+ were defined as HER2 positive (Fig. 1a,b). Hormone receptor (HR) expression was scored by assigning proportion and intensity scores according to procedures described by Allred et al.20 Briefly, the proportion score represented the estimated proportion of tumor nuclei staining positive: 0, no immunostaining; 1, <1% immunostaining; 2, 1–10% immunostaining; 3, 11–33% immunostaining; 4, 34–66% immunostaining; and 5, 67–100% immunostaining. The intensity score represented the average intensity of positive nuclei: 0, no immunostaining; 1, weak immunostaining; 2, moderate immunostaining; and 3, strong immunostaining. The proportion and intensity scores were then summed to obtain a total score, which could range from 0 to 8. In the present study, samples were defined as HR positive when either total scores for either ER or PR were >4 (Fig. 1c,d). Immunohistochemical evaluations were performed independently by two observers (ST and YS), with the median value used in analyses.

Figure 1.

Histopathological presentation of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. (a,c) Hematoxylin and eosin staining, original magnification ×200. (b) Immunohistochemical staining showing overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2; score 3+). Original magnification ×200. (d) Immunohistochemical staining showing expression of the estrogen receptor (Allred score 5 + 3 = 8). Original magnification ×200.

Statistical analysis

Inter‐group comparisons were made using the Chi‐squared test. Recurrence‐free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and differences were analyzed by log‐rank test. Independent prognostic significance was computed using Cox's proportional hazards general linear model for RFS and OS. The relative risk for relapse or death was estimated by hazard ratios (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered significant. These analyses were performed for all 71 cases of UPSC and for the 50 cases of pure‐type UPSC.

Results

Patients' clinicopathological information is presented in Table 1. Based on the FIGO classification system, 27, 13, 25 and 6 patients had Stage I, II, III, and IV disease, respectively. Of all 71 patients, 10 (14%) were HER2 positive and 37 (52%) were HR positive. Seven of 10 (70%) HER2‐postivite cases had FIGO Stage III or IV disease, compared with 24 of 61 (39%) HER2‐negative cases (P = 0.04). Furthermore, the recurrence rate was significantly higher in the HER2‐positive group than in the HER2‐negative group (P = 0.0024). In contrast, the incidence of lymph node metastasis, LVSI, and recurrence was significantly lower in HR‐positive patients (P = 0.005, P = 0.012, and P = 0.024, respectively) than in HR‐negative patients. There were no significant differences between the HER2‐positive and HER2‐negative groups with regard to histologic type, myometrial invasion, lymph node status, and LVSI. Similarly, there were no significant differences between the HR‐positive and HR‐negative groups regarding histologic type, stage, and myometrial invasion.

Table 1.

Correlation between clinicopathological parameters in uterine papillary serous carcinoma and human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 and hormone receptor status

| Total no. patients | HER2 | Hormone receptor* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 10) | Negative (n = 61) | P‐value | Positive (n = 37) | Negative (n = 34) | P‐value | ||

| Histologic subtype | |||||||

| Pure | 50 | 8 (80) | 42 (69) | 0.46 | 26 (70) | 24 (71) | 0.98 |

| Mixed | 21 | 2 (20) | 19 (31) | 11 (30) | 10 (29) | ||

| FIGO stage | |||||||

| I | 27 | 1 (10) | 26 (42) | 0.04 | 14 (38) | 13 (38) | 0.27 |

| II | 13 | 2 (20) | 11 (18) | 7 (19) | 6 (18) | ||

| III | 25 | 7 (70) | 18 (30) | 15 (40) | 10 (29) | ||

| IV | 6 | 0 (0) | 6 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (15) | ||

| Myometrial invasion (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 10 | 0 (0) | 10 (16) | 0.10 | 7 (19) | 3 (9) | 0.12 |

| <50 | 28 | 3 (30) | 25 (41) | 17 (46) | 11 (32) | ||

| >50 | 33 | 7 (70) | 26 (43) | 13 (35) | 20 (59) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||||

| Positive | 13 | 2 (20) | 11 (18) | 0.35 | 2 (6) | 11 (32) | 0.005 |

| Negative | 30 | 6 (60) | 24 (39) | 16 (43) | 14 (41) | ||

| Unknown | 28 | 2 (20) | 26 (43) | 19 (51) | 9 (27) | ||

| Lymph–vascular space involvement | |||||||

| Positive | 35 | 7 (70) | 28 (46) | 0.15 | 13 (35) | 22 (65) | 0.012 |

| Negative | 36 | 3 (30) | 33 (54) | 24 (65) | 12 (35) | ||

| Recurrence | |||||||

| Yes | 34 | 9 (90) | 25 (41) | 0.0024 | 13 (35) | 21 (62) | 0.024 |

| No | 37 | 1 (10) | 36 (59) | 24 (65) | 13 (38) | ||

Data show the number of patients in each group, with percentages given in parentheses. *Hormone receptor expression was classified as positive when the patient was positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

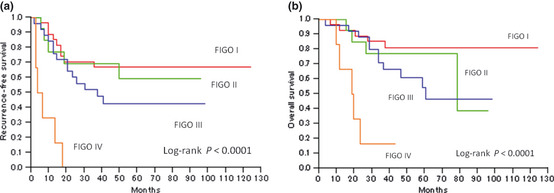

The median follow‐up time for all patients was 49.7 months (range 4–125 months). During this time, recurrence occurred in 34 patients (48%). Initial recurrence sites, either single or multiple, were as follows: lung (n = 12 patients), abdominal wall or cavity (n = 9), para‐aortic lymph nodes (n = 8), cervical or supraclavicular lymph nodes (n = 6), vagina (n = 3), liver (n = 3), bone (n = 3), pelvic cavity (n = 2) and brain (n = 1). Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for RFS and OS stratified according to FIGO stage. The RFS rates after 3 and 5 years were 56% and 51%, respectively, with 5‐year RFS significantly better for patients with early stage disease (Stage I, 67%; Stage II, 59%) than those with advanced stages of the disease (Stage III, 43%; Stage IV, 0%; P < 0.0001). The OS rates after 3 and 5 years were 73% and 66%, respectively; after 5 years, OS was again significantly higher in patients with early stage disease (Stage I, 81%; Stage II, 77%) than in patients at advanced stages of the disease (Stage III, 54%; Stage IV, 0%; P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma stratified according to International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages. Significant differences were observed between the groups for both (a) recurrence‐free survival and (b) overall survival (P < 0.0001, log‐rank test).

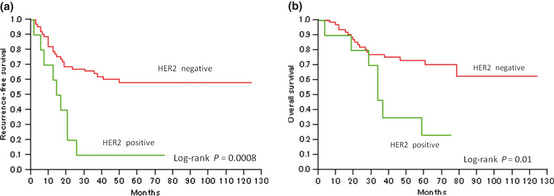

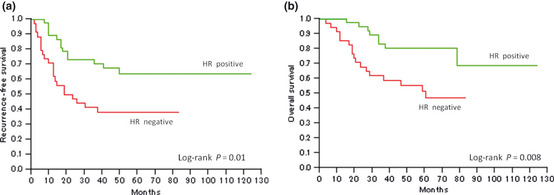

Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for RFS and OS in the HER2‐positive and ‐negative groups. Patients with HER2‐positive tumors had a significantly lower RFS and OS than patients with HER2‐negative tumors (P = 0.0008 and P = 0.01, respectively). In contrast, patients with HR‐positive tumors had significantly higher RFS and OS than patients with HR‐negative tumors (P = 0.01 and P = 0.008, respectively; Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma stratified according to human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) status. Significant differences were observed between the groups for both (a) recurrence‐free survival (P < 0.0008) and (b) overall survival (P = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma stratified according to hormone receptor (HR) status. Note, HR expression was classified as positive when the patient was positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors. Significant differences were observed between the groups for both (a) recurrence‐free survival (P = 0.01) and (b) overall survival (P = 0.008).

Patients were stratified into four groups according to both HER2 and HR status. The clinical outcome was best for patients in the HER2‐negative HR‐positive group, followed by the HER2‐negative HR‐negative group, the HER2‐positive HR‐positive group, and finally the HER2‐positive HR‐negative group, with corresponding 5‐year RFS/OS rates in these four groups of 68%/86%, 45%/58%, 43%/51%, and 0%/20%, respectively. The OS of HER2‐positive HR‐negative patients and HER2‐negative HR‐positive patients differed significantly (P = 0.0004). Similarly, OS for HER2‐negative HR‐negative patients and HER2‐positive HR‐negative patients differed significantly (P = 0.02). However, there were no significant differences in OS between the HER2‐negative HR‐negative group and any of the three other groups. The results of univariate analysis of the effects of various clinicopathological factors on RFS are given in Table 2. All factors examined, except lymph node status, were significantly associated with a worse patient outcome. We also performed multivariate analysis using Cox's proportional hazards model including HER2, HR, histologic type, stage, myometrial invasion, and LVSI. Multivariate analysis identified HER2, HR, and histologic type as independent prognostic factors for RFS (P = 0.022, P = 0.018, and P = 0.01, respectively). The results of univariate analysis of the effects of various clinicopathological factors on OS are given in Table 3. All factors examined, except lymph node status, were significantly associated with a worse patient outcome. We also performed multivariate analysis including HER2, HR, histologic type, stage, myometrial invasion, and LVSI. This analysis revealed that HR was the only independent factor associated with OS (P = 0.044).

Table 2.

Cox model estimates of the prognostic significance of each parameter for recurrence‐free survival

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‐value | HR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| HER2 | ||||||

| Positive | 3.43 | 1.50–7.23 | 0.005 | 2.94 | 1.18–6.90 | 0.022 |

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Hormone receptora | ||||||

| Positive | 0.41 | 0.20–0.82 | 0.011 | 0.41 | 0.18–0.86 | 0.018 |

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Histologic subtype | ||||||

| Pure | 1.00 | 0.013 | 0.01 | |||

| Mixed | 0.58 | 0.34–0.90 | 0.54 | 0.30–0.87 | ||

| FIGO stage | ||||||

| I or II | 1.00 | 0.013 | 1.00 | 0.19 | ||

| III or IV | 1.54 | 1.09–2.19 | 1.28 | 0.88–1.88 | ||

| Myometrial invasion (%) | ||||||

| ≤50 | 1.00 | 0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.97 | ||

| >50 | 2.00 | 1.40–2.97 | 1.02 | 0.49–1.98 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| Positive | 1.86 | 1.07–3.03 | 0.085 | |||

| Negative | 1.00 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.78 | 0.48–1.24 | ||||

| Lymph–vascular space involvement | ||||||

| Positive | 1.87 | 1.31–2.77 | 0.0005 | 1.51 | 0.80–3.06 | 0.21 |

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

Hormone receptor expression was classified as positive when the patient was positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors. HR, hazards ratio; CI, confidence interval; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Table 3.

Cox model estimates of the prognostic significance of each parameter for overall survival

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‐value | HR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| HER2 | ||||||

| Positive | 3.00 | 1.15–7.01 | 0.026 | 2.06 | 0.77–5.04 | 0.144 |

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Hormone receptora | ||||||

| Positive | 0.34 | 0.14–0.76 | 0.0084 | 0.41 | 0.16–0.98 | 0.044 |

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Histologic subtype | ||||||

| Pure | 1.00 | 0.039 | 1.00 | 0.087 | ||

| Mixed | 0.60 | 0.32–0.98 | 0.63 | 0.33–1.07 | ||

| FIGO stage | ||||||

| I or II | 1.00 | 0.011 | 1.00 | 0.246 | ||

| III or IV | 1.68 | 1.13–2.59 | 1.29 | 0.84–2.05 | ||

| Myometrial invasion (%) | ||||||

| ≤50 | 1.00 | 0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.385 | ||

| >50 | 2.65 | 1.68–4.60 | 1.45 | 0.64–3.38 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| Positive | 2.08 | 1.14–3.59 | 0.062 | |||

| Negative | 1.00 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.63 | 0.34–1.10 | ||||

| Lymph–vascular space involvement | ||||||

| Positive | 2.38 | 1.51–4.13 | 0.0001 | 1.47 | 0.68–3.47 | 0.344 |

| Negative | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

Hormone receptor expression was classified as positive when the patient was positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors. HR, hazards ratio; CI, confidence interval; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Separate univariate and multivariate analyses using the Cox's proportional hazards model were also performed for the 50 cases of pure‐type UPSC (data not shown). In these patients, HER2, HR, and LVSI were identified as independent prognostic factors for RFS (P = 0.006, P = 0.018, and P = 0.04, respectively). Similarly, HR tended towards being an independent prognostic factor for OS (P = 0.06).

Discussion

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma is an aggressive variant of endometrial carcinoma but, because it is so rare, little is known about the prognostic markers for this disease. In the present study, we found that HER2 and HR were prognostic markers of UPSC.

In the present study, the 5‐year OS rate after initial surgery for UPSC was 66%; furthermore, the 5‐year OS was significantly better for patients in the early stages of the disease (Stages I and II) than in the advanced stages (Stages III and IV). Other studies have reported OS rates of 37–57%, with better rates for patients in the early stages of the disease.7, 21, 22 Based on the FIGO annual report,23 76.5% of endometrial cancer patients are alive at 5 years. We confirmed the poor prognosis of UPSC compared with endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus. Assessing patterns of recurrence revealed that lung and abdominal failure occurred frequently. Wang et al.24 reported that more than half of the patients who developed recurrence had abdominal failure. Furthermore, UPSC has a propensity to recur at distant sites, with metastases including lung, lymph nodes, liver, bone, and brain. In contrast, vaginal recurrence is less frequent than in endometrioid adenocarcinomas. An interesting aspect of UPSC is that even patients with no myometrial invasion have extrauterine disease.7, 8, 10, 25, 26 In the present series, 40% (4/10) of patients without myometrial invasion had extrauterine disease. Therefore, it is very important to perform accurate surgical staging for all patients with UPSC, regardless of the extent of myometrial invasion.

Overexpression of HER2 is frequently associated with more aggressive disease in cancer patients27 and a worse prognosis in breast cancer.28, 29, 30 However, there is little information regarding the relationship between HER2 expression and prognosis in patients with UPSC. In the present study, the frequency of HER2 overexpression in UPSC was found to be 14% (10/71). Halperin et al.31 reported that 45% (10/22) of UPSC samples were positive for HER2. Santin et al.32 noted HER2 expression in 16 of 26 (62%) UPSC samples. In the present study, we observed a low rate of HER2 overexpression compared with the rates reported in these earlier, smaller studies. Other larger scale studies have also reported a lower rate of HER2 overexpression, similar to the findings in the present study. For example, Slomovitz et al.33 and Konecny et al.34 have reported HER2 overexpression in only 18% (12/68) and 17% (18/105) of tumors.

With regard to clinicopathological parameters, patients in the HER2‐positive group were at more advanced stages of the disease and experienced a higher rate of recurrence than patients in the HER2‐negative group. Furthermore, the HER2‐positive group had lower RFS and OS than the HER2‐negative group. Few other studies have evaluated the prognostic value of HER2 in UPSC. Slomovitz et al.33 reported that HER2 overexpression was associated with a lower OS (P = 0.008). They also reported that, in multivariate analysis, HER2 overexpression, lymph node status, and stage were each correlated with OS (P < 0.05).33

In our multivariate analysis, HER2 overexpression was an independent prognostic factor for RFS (HR 2.94; 95% CI 1.18–6.90; P = 0.022), but not for OS. The latter negative result may have been due to the small number of UPSC patients in the follow‐up, and the small number with HER2 overexpression (10 cases).

Both ER and PR are present in normal endometrial tissue as well as in endometrial carcinoma. It is known that HR‐positive breast cancers and Type I endometrial carcinomas, both associated with a hyperestrogenic state, have a better clinical outcome than HR‐negative breast cancers and Type II endometrial cancers, which are not associated with a hyperestrogenic state. In endometrial cancers, the absence of HRs is considered an indicator of aggressive tumor growth and poor patient prognosis.16, 35, 36, 37 Therefore, we propose that Type II endometrial carcinoma with HR expression is associated with a good prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated the prognostic value of ER and PR in UPSC. The present study is the largest correlating ER and PR expression with the clinical outcome of UPSC patients. The frequency of HR expression in our UPSC cohort was 52% (37/71). Reported frequencies of ER and PR expression in previous studies from 23.8% to 50% for ER and from 19% to 45.5% for PR.38, 39, 40 Therefore, UPSC frequently express ER and PR despite being unrelated to estrogenic stimulation.

In terms of clinicopathological parameters, the HR‐positive group did not have pelvic lymph node metastasis and had negative LVSI and lower recurrence rates than the HR‐negative group. Moreover, HR expression was significantly associated with higher RFS and OS. Fukuda et al.15 reported that ER/PR‐positive cases had significantly higher disease‐free survival rates in endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus. However, there appears to be no information in the literature regarding the significance of HRs as prognostic parameters in UPSC. In the present study, multivariate analysis revealed that HR expression was an independent prognostic indicator for RFS (HR 0.41; 95% CI 0.18–0.86; P = 0.018) and OS (HR 0.41; 95% CI 0.16–0.98; P = 0.044). Furthermore, HR expression was the only independent favorable prognostic factor for OS: Other factors, such as FIGO stage, histologic subtype, myometrial invasion, lymph node status, and LVSI, lost their prognostic significance. No other studies have investigated HR expression as a prognostic factor for RFS and OS in patients with UPSC. In the present study, HRs were expressed less frequently in UPSC than reported for endometrioid carcinoma,38, 40 but still seem clinically useful for prognosis.

In the present study, there were 21 cases (30%) of mixed‐type UPSC. Mixed serous and endometrioid carcinomas containing at least 25% of the serous component have been shown to behave in the same way as pure serous carcinomas.41 Using univariate and multivariate analyses, we also showed that HER2 and HR were important prognostic factors for pure‐type UPSC. We assume that the results of the present study hold true for both pure‐ and mixed‐type UPSC.

The breast cancer group that lacks ER and PR expression and has HER2 protein overexpression is classified as the “triple‐negative” subtype, with the tumors characterized as aggressive and more likely to recur and metastasize than those of other subtypes.42 Kothari et al.3 reported that the triple‐negative phenotype in endometrial cancer was also associated with poor prognostic factors. However, in the present study, the prognosis of patients with triple‐negative UPSC was intermediate between those with HR‐positive HER2‐negative UPSC and HR‐negative HER2‐positive UPSC.

In conclusion, UPSC is an aggressive variant of endometrial carcinoma and the optimal therapy for this condition has not yet been developed. The significance of HER2 and HR for prognosis in UPSC was not sufficiently clear, but the present study has demonstrated that clinicopathological factors and molecular biological prognostic factors, such as HER2 and HR, are related to RFS and/or OS in patients with UPSC. Although UPSC is a rare tumor, it is mandatory to establish novel therapies, including chemotherapy, endocrine therapy and molecular‐targeted drug therapy, based on the findings of the status of these molecular biological markers.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any financial relationships relevant to this publication.

References

- 1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E et al Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 2006; 56: 106–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakao Y, Yokoyama M, Hara K et al MR imaging in endometrial carcinoma as a diagnostic tool for the absence of myometrial invasion. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 102: 343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kothari R, Morrison C, Richardson D et al The prognostic significance of the triple negative phenotype in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 118: 172–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel PJ, Cox RS, Martinez A, Kempson R. Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: analysis of 256 cases with carcinoma limited to the uterine corpus. Pathology review and analysis of prognostic variables. Gynecol Oncol 1982; 13: 373–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel P, Martinez A, Kempson R. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a highly malignant form of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1982; 6: 93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicklin JL, Copeland LJ. Endometrial papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of spread and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1996; 39: 686–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slomovitz BM, Burke TW, Eifel PJ et al Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC): a single institution review of 129 cases. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 91: 463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bristow RE, Asrari F, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Extended surgical staging for uterine papillary serous carcinoma: survival outcome of locoregional (Stage I–III) disease. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 81: 279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carcangiu ML, Chambers JT. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a study on 108 cases with emphasis on the prognostic significance of associated endometrioid carcinoma, absence of invasion, and concomitant ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1992; 47: 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grice J, Ek M, Greer B et al Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: evaluation of long‐term survival in surgically staged patients. Gynecol Oncol 1998; 69: 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meric‐Bernstam F, Hung MC. Advances in targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor‐2 signaling for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 6326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rabindran SK. Antitumor activity of HER‐2 inhibitors. Cancer Lett 2005; 227: 9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Friedlander E, Barok M, Szollosi J, Vereb G. ErbB‐directed immunotherapy: antibodies in current practice and promising new agents. Immunol Lett 2008; 116: 126–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Creasman WT. Prognostic significance of hormone receptors in endometrial cancer. Cancer 1993; 71: 1467–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fukuda K, Mori M, Uchiyama M, Iwai K, Iwasaka T, Sugimori H. Prognostic significance of progesterone receptor immunohistochemistry in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1998; 69: 220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nyholm HC, Christensen IJ, Nielsen AL. Progesterone receptor levels independently predict survival in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1995; 59: 347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pertschuk LP, Masood S, Simone J et al Estrogen receptor immunocytochemistry in endometrial carcinoma: a prognostic marker for survival. Gynecol Oncol 1996; 63: 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sobin LH, Wittekind C, eds. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 6th edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silverberg S, Mutter GL, Kurman RJ, Kubik‐Huch RA, Nogales F, Tavassoli FA. Tumours of the uterine corpus In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press, 2003; 224–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol 1998; 11: 155–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goldberg H, Miller RC, Abdah‐Bortnyak R et al Outcome after combined modality treatment for uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a study by the Rare Cancer Network (RCN). Gynecol Oncol 2008; 108: 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Low JS, Wong EH, Tan HS et al Adjuvant sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 97: 171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003; 83(Suppl. 1): ix–xxii, 1–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang W, Do V, Hogg R et al Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of failure and survival. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 49: 419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bristow RE, Duska LR, Montz FJ. The role of cytoreductive surgery in the management of Stage IV uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 81: 92–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goff BA, Kato D, Schmidt RA et al Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of metastatic spread. Gynecol Oncol 1994; 54: 264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Odicino FE, Bignotti E, Rossi E et al HER‐2/neu overexpression and amplification in uterine serous papillary carcinoma: comparative analysis of immunohistochemistry, real‐time reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction, and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008; 18: 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Konecny G, Pauletti G, Pegram M et al Quantitative association between HER‐2/neu and steroid hormone receptors in hormone receptor‐positive primary breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95: 142–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Menard S, Valagussa P, Pilotti S et al Response to cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in lymph node‐positive breast cancer according to HER2 overexpression and other tumor biologic variables. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 329–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER‐2/neu oncogene. Science 1987; 235: 177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Halperin R, Zehavi S, Habler L, Hadas E, Bukovsky I, Schneider D. Comparative immunohistochemical study of endometrioid and serous papillary carcinoma of endometrium. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2001; 22: 122–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santin AD, Bellone S, Van Stedum S et al Determination of HER2/neu status in uterine serous papillary carcinoma: comparative analysis of immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 98: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Slomovitz BM, Broaddus RR, Burke TW et al Her‐2/neu overexpression and amplification in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Konecny GE, Santos L, Winterhoff B et al HER2 gene amplification and EGFR expression in a large cohort of surgically staged patients with nonendometrioid (Type II) endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 100: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ferrandina G, Ranelletti FO, Gallotta V et al Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2), receptors for estrogen (ER), and progesterone (PR), p53, ki67, and neu protein in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 98: 383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jazaeri AA, Nunes KJ, Dalton MS, Xu M, Shupnik MA, Rice LW. Well‐differentiated endometrial adenocarcinomas and poorly differentiated mixed mullerian tumors have altered ER and PR isoform expression. Oncogene 2001; 20: 6965–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kadar N, Malfetano JH, Homesley HD. Steroid receptor concentrations in endometrial carcinoma: effect on survival in surgically staged patients. Gynecol Oncol 1993; 50: 281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alkushi A, Irving J, Hsu F et al Immunoprofile of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas using a tissue microarray. Virchows Arch 2003; 442: 271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alkushi A, Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Gilks CB. High‐grade endometrial carcinoma: serous and Grade 3 endometrioid carcinomas have different immunophenotypes and outcomes. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2010; 29: 343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kounelis S, Kapranos N, Kouri E, Coppola D, Papadaki H, Jones MW. Immunohistochemical profile of endometrial adenocarcinoma: a study of 61 cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sherman ME, Bitterman P, Rosenshein NB, Delgado G, Kurman RJ. Uterine serous carcinoma. A morphologically diverse neoplasm with unifying clinicopathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol 1992; 16: 600–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Badve S, Dabbs DJ, Schnitt SJ et al Basal‐like and triple‐negative breast cancers: a critical review with an emphasis on the implications for pathologists and oncologists. Mod Pathol 2011; 24: 157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]