Abstract

Arecoline, the major alkaloid of areca nut, has been shown to cause strong genotoxicity and is considered a potential carcinogen. However, the detailed mechanism for arecoline‐induced carcinogenesis remains obscure. In this study, we noticed that the levels of p21 and p27 increased in two oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines with high confluence. Furthermore, when treated with arecoline, elevated levels of p21 and p27 could be downregulated through the reactive oxygen species/mTOR complex 1 (ROS/mTORC1) pathway. Although arecoline decreased the activity of mTORC1, the amounts of autophagosome‐like vacuoles or type II LC3 remained unchanged, suggesting that the downregulation of p21 and p27 was independent of autophagy‐mediated protein destruction. Arecoline also caused DNA damage through ROS, indicating that the reduced levels of p21 and p27 might facilitate G 1/S transition of the cell cycle and subsequently lead to error‐prone DNA replication. In conclusion, these data have provided a possible mechanism for arecoline‐induced carcinogenesis in subcytolytic doses in vivo. (Cancer Sci 2012; 103: 1221–1229)

Oral cancer is one of the most common cancers, resulting in 128 000 deaths worldwide in 2008.1 Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is frequently found on the tongue and buccal, as well as gingival areas and accounts for more than 90% of oral cancer incidence.2 In addition to cigarettes and alcohol, betel quid is a risk factor of oral cancer.1 Betel quid is composed of areca nut, lime, and Piper betle leaf. Being a major alkaloid in areca nut, arecoline has long been considered a potential carcinogen. Several reports showed that arecoline may increase reactive oxygen species (ROS), retard the cell cycle, and induce apoptosis.3, 4 Arecoline was also proved to enhance unscheduled DNA synthesis that caused strong genotoxicity in mouse germ cells.5 In addition, arecoline impeded DNA repair and mitotic spindle assembly.6, 7, 8 Recently, arecoline was suggested to regulate the expression of certain genes through epigenetic control.9

Cell cycle progression is dependent on sequential coordination among multiple proteins. In particular, cyclin levels can oscillate in different stages and interact with cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDKs), forming the cyclin/CDK complexes for promoting cell cycle progression.10 In contrast, p21 and p27 belong to the kinase inhibitor protein family and regulate the cell cycle in response to various stresses, such as DNA damage, hypoxia, and confluence stress.10, 11, 12, 13 For example, once activated by DNA damage sensors like ataxia telangiectasia mutated, p53 enhances p21 transcription to arrest cell cycle before G1/S transition for DNA repair.10

Reactive oxygen species consists of various radicals that are triggered by a range of agents and may exert different effects on downstream signaling pathways, including the levels of p21 and p27.14, 15 Deregulated ROS levels are strongly implicated in cancers.16 Reactive oxygen species can induce DNA damage that results in genomic instability and contributes to carcinogenesis.17, 18

The mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) is composed of mTOR, raptor, and GβL and is controlled by multiple pathways, such as PI3K‐Akt signaling. Activated mTORC1 facilitates protein synthesis through controlling various downstream factors including 4E‐BP1, p70S6K, and eEF2K, thus allowing release of eIF4E for translation initiation and activation of elongation factor 2 (eEF2) for translation elongation.19 Another important role of mTORC1 is to regulate autophagy. In conditions like energetic stress, mTORC1 may be inhibited by AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) to allow autophagy induction.20

This study was initiated from an interesting observation: upregulation of p21 and p27 in OSCC cells with high confluence could be downregulated by arecoline treatment. In 2003, the International Agency for Research on Cancer announced that betel quid and areca nut chewing were carcinogenic to humans. Arecoline is one of the most abundant alkaloids of areca nut, suggesting its potential role in carcinogenesis. Here, we show the mechanism behind arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27, which may be important for betel quid chewing oral carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Two OSCC cell lines, OCSL and OC2, derived from two Taiwanese men with habits of drinking alcohol, smoking, and areca nut chewing,21 were maintained in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells from a Japanese oral cancer cell line, Ca9‐22, were maintained in DMEM/F12 with similar supplements. Cells were routinely cultured in a 37°C incubator supplied with 5% CO2. 12–16 h after seeding, experiments were carried out when cell confluence reached 95% (high) or approximately 30–40% (low).

Reagents and antibodies

Arecoline, N‐acetylcysteine (NAC), nocodazole, 2′‐7′‐dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA), NH4Cl, and DMSO were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against phospho‐eEF2 (T56), eEF2K, phospho‐eEF2K (S366), phospho‐p70S6K (T389), phospho‐S6 (S235/236), LC3, and rapamycin were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against p21, p53, and phospho‐histone H3 (S10) were from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA, USA). Antibody against phospho‐4E‐BP1 (T45) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Antibody against p27 was from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and antibody against γH2AX was from Abnova (Walnut, CA, USA).

Areca nut extract (ANE) was prepared from fresh nuts. In brief, the nuts were chopped into 0.5–1 cm3 pieces by a blender and the water‐soluble ingredients were extracted at 4°C overnight. The supernatant was harvested and concentrated by −70°C lyophilisation. The powder derived from water extract was weighed, redissolved in ddH2O, and stored at −20°C before experimental use.

Cell lysate preparation and Western blot analysis

Cells in 24‐well plates were washed twice with PBS and lysed with 70 μL 4× Laemmli loading buffer, followed by boiling for 10 min. Equal amounts of samples were run on SDS‐PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Expression of individual proteins was detected using corresponding antibodies, followed by the secondary antibody conjugated with HRP. After incubation with ECL, the membranes were exposed to X‐ray film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Cell proliferation assay

Cells with 30–40% or more than 95% confluence were treated with the indicated reagents. One or 2 days later, MTT reagent (Sigma) with 1 mg/mL final concentration was added to each well. Plates were swirled gently for 5 s and cultured continuously for 3 h. After incubation, medium was removed. Cells were washed twice with PBS and MTT metabolic product was resuspended in 500 μL DMSO. After swirling for seconds, 50 μL supernatant from each well was transferred to optical plates for detection at 595 nm.

Detection of ROS

The OSCC cells were treated with 0.5 mM arecoline. After 6 or 12 h, medium was removed and cells were incubated in PBS containing 10 μM DCFDA for approximately 30 min. Cells were observed using a fluorescence microscope and photographed. For quantifying the level of ROS, cells cultured in 24‐well plates were treated with arecoline as indicated, and 50 μM DCFDA was added 30 min before harvesting cells. Cells were finally washed once with PBS and dissolved in 200 μL DMSO containing 1 mM NAC for quenching reaction. After swirling for 5–10 s, 50 μL supernatant was transferred for fluorescence evaluation.

Real‐time PCR

Cells were harvested for RNA extraction using TriPure reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) 24 h after treatment with 0.5 mM arecoline. After cDNA synthesis, the reaction was carried out as previously described.22

Cell cycle analysis

Cells seeded in six‐well plates were treated with or without 0.5 mM arecoline for 24 h. The detailed procedures of cell cycle analysis were as described.6

Incorporation of BrdU

After attachment, cells were starved in serum‐free medium for 1 day. Subsequently, cells were cultured in fresh medium containing 10% FBS with or without 0.5 mM arecoline for 24 or 30 h. Twelve hours after addition of FBS, BrdU was added at final concentration 10 μM. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and fixed in ice‐cold 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 20 min. After washing with PBS again, cells were incubated in 1 N HCl for 30 min, followed by washing with Tris buffer (pH 7.4) three times, and stained with anti‐BrdU antibodies at 4°C with gentle swirling overnight. After PBS washing, cells were then incubated with second antibodies conjugated with Alexa 555 at room temperature for 3–4 h. After final washing, incorporation of BrdU was observed using a fluorescence microscope and photographed. For quantification, treated cells were harvested by trypsinization and fixed with 70% ice‐cold ethanol, followed by the procedures above except that different secondary antibodies were used. Cells were finally sent for flow cytometry analysis after propidium iodide staining.

Results

Arecoline downregulates p21 and p27 in OSCC cells with high confluence

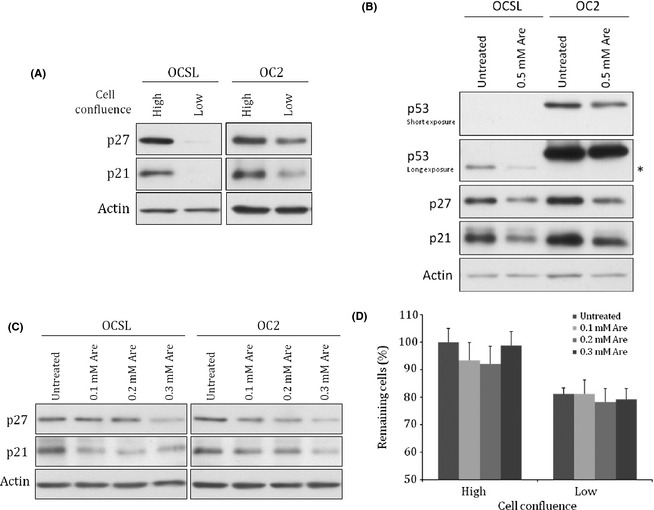

Two OSCC cell lines, OCSL and OC2, were established from patients from middle Taiwan.21 In attempt to evaluate the effect of arecoline on these two cell lines, we noticed that the protein levels of p21 and p27 fluctuated dramatically depending on the confluence of harvested cells (Fig. 1A). Arecoline (0.5 mM) downregulated p21 and p27 in high‐confluence OSCC cells (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of arecoline was not significant at a lower confluence (Fig. S1). Cell cycle regulators such as CDK inhibitors p21 and p27 in cultured cells at high density are usually increased to induce cell cycle arrest contact inhibition. In contrast, reduction of p21 and/or p27 may decrease the sensitivity to contact inhibition and facilitate continuous cell growth.23, 24, 25, 26 We therefore speculated that downregulation of p21 and/or p27 could play a role in carcinogenesis of betel quid‐dependent oral cancers. However, 0.5 mM arecoline also caused detectable cell death (data not shown). Thus, we adopted lower doses of arecoline to rule out possible cytotoxic effects. Arecoline at lower concentrations had no effect on cell growth but still decreased p21 and p27 in OSCC cells with high confluence (Fig. 1C,D, Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Protein levels of p21 and p27 were upregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells with high confluence and were downregulated by arecoline. (A) OCSL and OC2 cells with different percentages of confluence were harvested for analyzing the protein levels of p21 and p27 by Western blot. (B) OCSL and OC2 cells with high confluence were mock treated or treated with 0.5 mM arecoline (Are) for 24 h and harvested for analyzing p21 and p27. *Truncated form of p53. (C) OC2 cells treated with lower concentrations of arecoline (0.1–0.3 mM) were harvested for analyzing p21 and p27. (D) OC2 cells were treated with low doses of arecoline when cell confluence reached 95% (high) or 30–40% (low) and were harvested for MTT assay 24 h later. Actin protein was used as the loading control in panels A–C.

Arecoline enhances ROS in OSCC cells

To ask how arecoline could downregulate p21 and p27, we first checked the endogenous level of p53. Interestingly, OCSL showed weak expression of a truncated form of p53 and OC2 cells possessed mutant p53 (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the downregulation of p21 and p27 was mediated through a p53‐independent pathway.27

Arecoline had been proven to positively induce ROS in various cell types,4, 28 so we hypothesized that arecoline regulated the levels of p21 and p27 through a ROS‐dependent pathway. In order to prove this hypothesis, we examined arecoline‐induced ROS in these two OSCC cells. Production of ROS in both OCSL and OC2 cells was enhanced in the presence of arecoline using the fluorescent ROS detector DCFDA (Fig. 2A). Treating the cells with different concentrations of arecoline induced ROS in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner, with the exception for the highest dose (2.5 mM) that caused cytotoxicity (Fig. 2B,C). To confirm the effect of arecoline on ROS, NAC (a ROS quencher) was used to block the function of ROS. As shown in Figure 2D, the growth‐inhibitory effect of arecoline could be significantly counteracted in the presence of NAC.

Figure 2.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by arecoline (Are). (A) OCSL and OC2 cells were treated with 0.5 mM arecoline for 6 and 12 h, respectively, and stained with 2′‐7′‐dichlorofluorescin diacetate for ROS detection using a fluorescence microscope. For ROS quantification, OC2 cells were treated with different doses of arecoline for 2 h (B) or 0.5 mM arecoline for indicated time periods (C). Relative ROS levels were assayed using untreated samples in each time point as 1. *Significant difference from untreated cells (P < 0.05). (D) OSCC cells with low confluence were treated with 0.5 mM arecoline in combination with or without 2 mM N‐acetylcysteine (NAC) for 48 h and cell numbers were evaluated using MTT assay. Data were obtained from three independent experiments, each of which was done in triplicate. *Significant difference from untreated cells (DMSO) (P < 0.05).

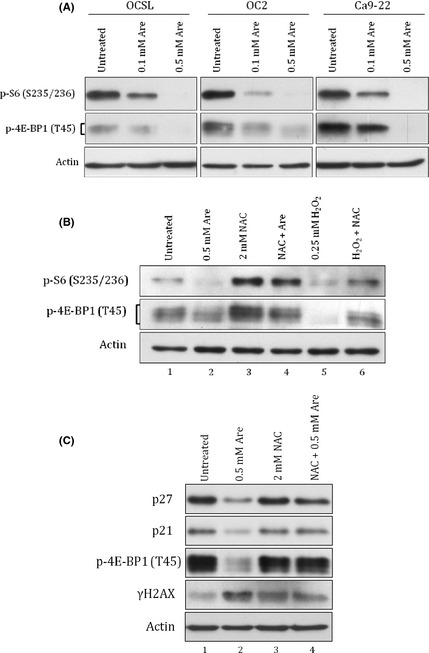

Arecoline strongly inhibits mTORC1 signaling

Previous studies also indicated that synthesis and activity of p21 and p27 were regulated by mTORC1.29, 30, 31, 32 To test if arecoline downregulated p21 and p27 through the mTORC1 pathway, we examined the effect of arecoline on mTORC1 activity. Arecoline strongly inactivated mTORC1 activity in all three tested OSCC cell lines as evidenced by the decreased amounts of phosphorylated 4E‐BP1 and S6 (Fig. 3A). Downregulation of other mTORC1 downstream factors including p70S6K, eEF2, and eEF2K further confirmed the inhibitory effect of arecoline on mTORC1 activity (Fig. S2). To verify whether this inhibitory effect was linked to the ROS pathway, mTORC1 activities were examined in OCSL cells cotreated with arecoline and NAC. The NAC completely abolished the inhibitory effect of arecoline and rescued mTORC1 activity (Fig. 3B, lane 2 vs lane 4), highly suggesting that arecoline inhibited mTORC1 through a ROS‐dependent pathway. We then used the mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin, to confirm that p21 and p27 expression could be regulated by mTORC1 signaling in OSCC cells. Indeed, rapamycin alone was sufficient to decrease p21 and p27 (Fig. S3A), whereas arecoline failed to downregulate p21 or p27 after treatment with NAC (Fig. 3C, lane 2 vs lane 4). Interestingly, treatment using arecoline did not decrease transcripts of p21 but increased transcripts of p27 significantly, suggesting that arecoline regulated p21 and p27 in a post‐transcriptional way (Fig. S3B). In addition, PI3K‐Akt and AMPK signaling are two well‐known upstream regulators of mTORC1.33 Unexpectedly, arecoline had no effect on PI3K‐AKT activation despite the strong inhibition in S6 phosphorylation (Fig. S4). Unlike PI3K‐Akt, activated AMPK was reported to inhibit mTORC1.33 However, arecoline inactivated the activity of AMPK as evidenced by the decrease of AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. S5A).4 Inhibition of AMPK by compound C also caused no significant influence on p21 and p27 (Fig. S5B). Taken together, these data indicate that arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 in OSCC cells was mediated through a novel, ROS/mTORC1‐dependent, but Akt‐ and AMPK‐independent pathway.

Figure 3.

Arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 was mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)‐dependent. (A) Oral squamous cell carcinoma cells (OCSL and OC2) and gingival cells (Ca9‐22) were treated with indicated doses of arecoline (Are) for 24 h and harvested for detecting mTORC1 activities by monitoring the phosphorylation of S6 and 4E‐BP1. (B) OCSL cells treated with 0.5 mM arecoline or 0.25 mM H2O2 in combination with or without 2 mM N‐acetylcysteine (NAC) were examined for mTORC1 activities. (C) OC2 cells treated with 0.5 mM arecoline in combination with or without 2 mM NAC were examined for levels of p21, p27, p‐4E‐BP, and γH2AX. Actin protein was used as the loading control.

Arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 might be autophagy‐independent

mTORC1 has been shown to promote protein translation but inhibit autophagy.20 Autophagy was reported to play roles in degradation of cytosolic proteins, organelles, or pathogens in a non‐selective manner.34 Accumulating evidence suggests that autophagy could be involved in the selective degradation of proteins through p62‐mediated ubiquitination.35, 36 Areca nut extracts have been reported to induce autophagy in OSCC cells,37, 38 suggesting that downregulation of p21 and p27 might be through autophagy‐mediated protein degradation. Thus, it was critical to understand whether arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 involved the autophagy pathway. Surprisingly, as shown in Figure 4(A), ANE but not arecoline strongly induced autophagosome‐like vacuoles in OC2 cells. Arecoline‐induced autophagosome‐like vacuoles were not significant even under the blockade of autophagic flow by NH4Cl (Fig. 4B). Therefore, we further investigated whether arecoline or ANE could induce production of type II LC3 (LC3‐II), a common indication of autophagy induction. Consistently, accumulation of LC3‐II was only observed in cells treated with ANE (Fig. 4C, lanes 4 and 5). However, arecoline but not ANE efficiently reduced phosphorylation of S6 (Fig. 4C, lane 3 vs lane 5). This result was confirmed by examining the phosphorylations of 4E‐BP and S6 in another oral cancer cell line Ca9‐22 (Fig. S6). Therefore, we concluded that arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 was not mainly through mTORC1‐dependent autophagy.

Figure 4.

Arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 was autophagy‐independent. Oral squamous cell carcinoma OC2 cells were photographed 24 h after treatment with indicated doses of arecoline (Are) or areca nut extracts (ANE) (A) and after treatment with 5 mM NH4Cl in combination with arecoline or ANE (B). (C) Phospho‐S6 and type II LC3 (LC3‐II) were examined in oral squamous cell carcinoma OCSL cells. Actin protein was used as the loading control. Magnification 200×. Rapa, rapamycin.

Arecoline‐treated cells bypass G 1/S checkpoint in spite of DNA damage

Both p21 and p27 play important roles in maintaining genome integrity during cell cycle progress. It is known that p21 and p27 can be upregulated to arrest cells mainly at the G1/S checkpoint for genome repair.10 As ROS is thought to cause DNA damage,39 we speculated that arecoline‐induced p21 and p27 downregulation may result in a less stringent G1/S checkpoint, and thus increased the possibility of error‐prone DNA replication, leading to arecoline‐induced carcinogenesis. Indeed, arecoline induced DNA damage as indicated in the increase of γH2AX (Fig. 3C, lane 1 vs lane 2) and enhanced cell populations at the G2/M stage in unsynchronized OC2 cells (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, arecoline also increased the cell population in S stage in addition to the G2/M stage. This increase is also indirect evidence for enhanced G1/S transition. However, using BrdU incorporation assay, we found that DNA replication in synchronized OC2 cells was not obviously affected by arecoline as compared to the serum starvation control (Fig. 5B). Under such conditions, the strong increase of γH2AX indicated that arecoline treatment induced DNA damage but still allowed cell transition into G2/M as evidenced by the increase of histone H3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5C, lane 1 vs lane 2). Consistently, synchronized cells treated with arecoline for a longer time clearly increased the population retarded at G2/M with completed DNA replication, as evidenced by a higher percentage of incorporated BrdU and phosphorylated H3 (Fig. 5D). These results suggested that genome replication still proceeded in spite of DNA damage.

Figure 5.

Arecoline bypassed the G 1/S checkpoint in spite of DNA damage in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. (A) The effect of arecoline (Are) on the cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h after treatment. (B) Synchronized OC2 cells were harvested for BrdU labeling (B) or Western blot analysis (C) for phospho‐histone H3 and γH2AX. Actin protein was used as the loading control. (D) OC2 cells were harvested for flow cytometry analysis using propidium iodide (PI)–BrdU dual labeling or PI–phospho‐H3 dual labeling 30 h after arecoline treatment.

Discussion

In this study, we showed an interesting observation that the levels of p21 and p27 were obviously upregulated, particularly in high confluence of OSCC cells. Several studies have indicated that cell confluence affects protein expression or function in malignant cells. For example, accumulation of HSP27 during high confluence increases resistance against anticancer drugs in colon cancer cells.40 CD26 also has a confluence‐dependent expression pattern in colon adenocarcinoma cell lines HCT‐116 and HCT‐15.41 Therefore, the arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 in confluent cells might play an important role in regulating the mechanism of oral carcinogenesis. Here, we illustrated the potential roles of p21 and p27 in arecoline‐induced oral carcinogenesis.

Several factors could affect the cellular levels of p21 and p27, including gene expression, stability, and intracellular localization.42, 43 For example, active p53 increases the expression of p21 and p27 to arrest cells.44, 45 In human epithelial cells, arecoline was reported to decrease p53–p21 signaling and repress DNA repair.6 Given that p53 was either weakly expressed or mutated in the two oral cancer cell lines, it is conceivable that p53 was not the major factor accounting for arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 (Fig. 1B).27 Instead, we showed that mTORC1 played an important role in this biological effect.

However, the detailed mechanism by which mTORC1 regulates the levels of p21 and p27 remains unclear. One possible mechanism is through the autophagy degradation pathway. However, 10 nM rapamycin is sufficient to downregulate p21 and p27 but fails to increase autophagosome‐like vacuoles or LC3‐II simultaneously (data not shown and Fig. 4C, lane 8), highly suggesting that downregulation of p21 and p27 might not be through the mTORC1‐dependent autophagy degradation pathway. The other possible mechanism is through protein synthesis, as arecoline affected translational machinery like S6 (Fig. 3A,B) and eEF2, which is known to mediate GTP‐dependent translocation of synthesizing peptide chain from A‐site to P‐site in ribosomes.46 In addition, mTORC1 was reported to phosphorylate SGK1 and modulate the function of p27.31

As important regulators at cell cycle checkpoints, p21 and p27 are frequently considered as tumor suppressors. Reduction of p21 and/or p27 possibly facilitates deregulated proliferation or insensitive to contact inhibition.23, 26, 47 Several studies have indicated the prognostic potential of p27 in various cancers, including oral cancers.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 It was shown that p27 could induce senescence in cancer cells and was considered a checkpoint for limiting the progression of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive cancer.54 Unlike p27, the role of p21 remains controversial.55, 56 Previous studies regarding the prognostic application of p21 in different stages of OSCC were inconsistent.48, 57, 58, 59, 60 It remains unclear whether these inconsistencies result from p21 polymorphism, which may be associated with oral malignancy.61

Long‐term exposure of betel quid, which is composed of areca nut, lime, and Piper betle leaf, is frequently associated with the induction of carcinogenesis in the oral cavity.1 However, the detailed mechanism behind betel quid chewing carcinogenesis is still elusive. Arecoline is the major alkaloid in areca nut. According to previous studies, the detected concentration of arecoline in betel quid chewers' saliva was approximately 0.3 mM or 0.1–10 μg/mL, with the sudden peak concentration of approximately 100 μg/mL during betel quid chewing.6, 62 This urged us to propose a model as shown in Figure 6: the arecoline concentration in the oral cavity of betel quid chewers may fluctuate dramatically in vivo. The sudden impact of high concentrations of arecoline may induce DNA damage through the ROS pathway and prevent increases of p21 and p27 through the ROS/mTORC1 pathway simultaneously, leading to a bypass of the G1/S checkpoint. Once betel quid is removed, cells are allowed to continue proliferation through G2/M presumably without genomic integrity. Finally, in combination with other unidentified factors, such as p53 mutation, arecoline leads to the deregulated growth of surviving cells, accounting for the mechanism of arecoline‐induced carcinogenesis.

Figure 6.

Proposed model for arecoline‐induced carcinogenesis. Arecoline induced reactive oxygen species (ROS), followed by downregulation of p21 and p27 through mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and increased susceptibility to DNA damage. Low amounts of p21 and p27 may result in a less stringent G 1/S checkpoint and the ensuing error‐prone DNA replication, leading to deregulated growth of cells.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Effects of arecoline on p21 and p27 in OCSS cells with different cell confluence.

Fig. S2. Inhibition of mTORC1 activity by arecoline.

Fig. S3. (A) Rapamycin (10 nM) was sufficient to downregulate levels of p21 and p27. (B) Relative transcription levels of p21 and p27 after 0.5 mM arecoline treatment for 24 h.

Fig. S4. Independence of PI3K‐Akt signaling on arecoline‐mediated mTORC1 inhibition.

Fig. S5. Independence of AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling on arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells.

Fig. S6. Strong inhibition of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) activities by arecoline rather than by areca nut extract (ANE).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Chun‐Jen Wang for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan (97‐2311‐B‐194‐001‐MY3 and NSC‐99‐2314‐B‐705‐002‐MY2).

References

- 1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen YK, Huang HC, Lin LM, Lin CC. Primary oral squamous cell carcinoma: an analysis of 703 cases in southern Taiwan. Oral Oncol 1999; 35: 173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tseng SK, Chang MC, Su CY et al Arecoline induced cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and cytotoxicity to human endothelial cells. Clin Oral Investig 2011; doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0604-1 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yen CY, Lin MH, Liu SY et al Arecoline‐mediated inhibition of AMP‐activated protein kinase through reactive oxygen species is required for apoptosis induction. Oral Oncol 2011; 47: 345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sinha A, Rao AR. Induction of shape abnormality and unscheduled DNA synthesis by arecoline in the germ cells of mice. Mutat Res 1985; 158: 189–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsai YS, Lee KW, Huang JL et al Arecoline, a major alkaloid of areca nut, inhibits p53, represses DNA repair, and triggers DNA damage response in human epithelial cells. Toxicology 2008; 249: 230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiang SL, Jiang SS, Wang YJ et al Characterization of arecoline‐induced effects on cytotoxicity in normal human gingival fibroblasts by global gene expression profiling. Toxicol Sci 2007; 100: 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang YC, Tsai YS, Huang JL et al Arecoline arrests cells at prometaphase by deregulating mitotic spindle assembly and spindle assembly checkpoint: implication for carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol 2010; 46: 255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin PC, Chang WH, Chen YH, Lee CC, Lin YH, Chang JG. Cytotoxic effects produced by arecoline correlated to epigenetic regulation in human K‐562 cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2011; 74: 737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN. The cell cycle: a review of regulation, deregulation and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Prolif 2003; 36: 131–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gardner LB, Li Q, Park MS, Flanagan WM, Semenza GL, Dang CV. Hypoxia inhibits G1/S transition through regulation of p27 expression. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 7919–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steinman RA, Wentzel A, Lu Y, Stehle C, Grandis JR. Activation of Stat3 by cell confluence reveals negative regulation of Stat3 by cdk2. Oncogene 2003; 22: 3608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cuadrado M, Gutierrez‐Martinez P, Swat A, Nebreda AR, Fernandez‐Capetillo O. p27Kip1 stabilization is essential for the maintenance of cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 8726–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaneto H, Kajimoto Y, Fujitani Y et al Oxidative stress induces p21 expression in pancreatic islet cells: possible implication in beta‐cell dysfunction. Diabetologia 1999; 42: 1093–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deng X, Gao F, May WS Jr. Bcl2 retards G1/S cell cycle transition by regulating intracellular ROS. Blood 2003; 102: 3179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gibellini L, Pinti M, Nasi M et al Interfering with ROS metabolism in cancer cells: the potential role of quercetin. Cancers 2010; 2: 1288–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pelicano H, Carney D, Huang P. ROS stress in cancer cells and therapeutic implications. Drug Resist Updat 2004; 7: 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manda G, Nechifor MT, Neagu T‐M. Reactive oxygen species, cancer and anti‐cancer therapies. Curr Chem Biol 2009; 3: 342–66. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang X, Proud CG. The mTOR pathway in the control of protein synthesis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006; 21: 362–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ 2005; 12(Suppl 2): 1509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang TT, Chen JY, Tseng CE et al Decreased GRP78 protein expression is a potential prognostic marker of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2010; 109: 326–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pang PH, Lin YH, Lee YH, Hou HH, Hsu SP, Juan SH. Molecular mechanisms of p21 and p27 induction by 3‐methylcholanthrene, an aryl‐hydrocarbon receptor agonist, involved in antiproliferation of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol 2008; 215: 161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. St Croix B, Sheehan C, Rak JW, Florenes VA, Slingerland JM, Kerbel RS. E‐Cadherin‐dependent growth suppression is mediated by the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor p27(KIP1). J Cell Biol 1998; 142: 557–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levenberg S, Yarden A, Kam Z, Geiger B. p27 is involved in N‐cadherin‐mediated contact inhibition of cell growth and S‐phase entry. Oncogene 1999; 18: 869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang JQ, Rudiger JJ, Hughes JM et al Cell density and serum exposure modify the function of the glucocorticoid receptor C/EBP complex. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008; 38: 414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang ZY, Wu Y, Hedrick N, Gutmann DH. T‐cadherin‐mediated cell growth regulation involves G2 phase arrest and requires p21(CIP1/WAF1) expression. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23: 566–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fan LC, Chiang WF, Liang CH et al alpha‐Catulin knockdown induces senescence in cancer cells. Oncogene 2011; 30: 2610–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hung TC, Huang LW, Su SJ et al Hemeoxygenase‐1 expression in response to arecoline‐induced oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J Cardiol 2011; 151: 187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Law M, Forrester E, Chytil A et al Rapamycin disrupts cyclin/cyclin‐dependent kinase/p21/proliferating cell nuclear antigen complexes and cyclin D1 reverses rapamycin action by stabilizing these complexes. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 1070–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beuvink I, Boulay A, Fumagalli S et al The mTOR inhibitor RAD001 sensitizes tumor cells to DNA‐damaged induced apoptosis through inhibition of p21 translation. Cell 2005; 120: 747–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hong F, Larrea MD, Doughty C, Kwiatkowski DJ, Squillace R, Slingerland JM. mTOR‐raptor binds and activates SGK1 to regulate p27 phosphorylation. Mol Cell 2008; 30: 701–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee M, Theodoropoulou M, Graw J, Roncaroli F, Zatelli MC, Pellegata NS. Levels of p27 sensitize to dual PI3K/mTOR inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther 2011; 10: 1450–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2005; 17: 596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seglen PO, Gordon PB, Holen I. Non‐selective autophagy. Semin Cell Biol 1990; 1: 441–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 2010; 330: 1344–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: ubiquitin‐mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12: 836–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin MH, Hsieh WF, Chiang WF et al Autophagy induction by the 30‐100kDa fraction of areca nut in both normal and malignant cells through reactive oxygen species. Oral Oncol 2010; 46: 822–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu HH, Kao SY, Liu TY et al Areca nut extract induced oxidative stress and upregulated hypoxia inducing factor leading to autophagy in oral cancer cells. Autophagy 2010; 6: 725–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiseman H, Halliwell B. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer. Biochem J 1996; 313(Pt 1): 17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garrido C, Ottavi P, Fromentin A et al HSP27 as a mediator of confluence‐dependent resistance to cell death induced by anticancer drugs. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 2661–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abe M, Havre PA, Urasaki Y et al Mechanisms of confluence‐dependent expression of CD26 in colon cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer 2011; 11: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liang J, Zubovitz J, Petrocelli T et al PKB/Akt phosphorylates p27, impairs nuclear import of p27 and opposes p27‐mediated G1 arrest. Nat Med 2002; 8: 1153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhou BP, Liao Y, Xia W, Spohn B, Lee MH, Hung MC. Cytoplasmic localization of p21Cip1/WAF1 by Akt‐induced phosphorylation in HER‐2/neu‐overexpressing cells. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3: 245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. He G, Kuang J, Huang Z et al Upregulation of p27 and its inhibition of CDK2/cyclin E activity following DNA damage by a novel platinum agent are dependent on the expression of p21. Br J Cancer 2006; 95: 1514–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. He G, Siddik ZH, Huang Z et al Induction of p21 by p53 following DNA damage inhibits both Cdk4 and Cdk2 activities. Oncogene 2005; 24: 2929–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaul G, Pattan G, Rafeequi T. Eukaryotic elongation factor‐2 (eEF2): its regulation and peptide chain elongation. Cell Biochem Funct 2011; 29: 227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Motti ML, Califano D, Baldassarre G et al Reduced E‐cadherin expression contributes to the loss of p27kip1‐mediated mechanism of contact inhibition in thyroid anaplastic carcinomas. Carcinogenesis 2005; 26: 1021–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fillies T, Woltering M, Brandt B et al Cell cycle regulating proteins p21 and p27 in prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oncol Rep 2007; 17: 355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chu IM, Hengst L, Slingerland JM. The Cdk inhibitor p27 in human cancer: prognostic potential and relevance to anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8: 253–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Slingerland J, Pagano M. Regulation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and its deregulation in cancer. J Cell Physiol 2000; 183: 10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nickeleit I, Zender S, Kossatz U, Malek NP. p27kip1: a target for tumor therapies? Cell Div 2007; 2: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kudo Y, Kitajima S, Ogawa I, Miyauchi M, Takata T. Down‐regulation of Cdk inhibitor p27 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2005; 41: 105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kuo MY, Hsu HY, Kok SH et al Prognostic role of p27(Kip1) expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan. Oral Oncol 2002; 38: 172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Majumder PK, Grisanzio C, O'Connell F et al A prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia‐dependent p27 Kip1 checkpoint induces senescence and inhibits cell proliferation and cancer progression. Cancer Cell 2008; 14: 146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gartel AL. Is p21 an oncogene? Mol Cancer Ther 2006; 5: 1385–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 400–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tatemoto Y, Osaki T, Yoneda K, Yamamoto T, Ueta E, Kimura T. Expression of p53 and p21 proteins in oral squamous cell carcinoma: correlation with lymph node metastasis and response to chemoradiotherapy. Pathol Res Pract 1998; 194: 821–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nemes JA, Nemes Z, Marton IJ. p21WAF1/CIP1 expression is a marker of poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med 2005; 34: 274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Buim MEC, Fregnani JH, Lourenço SV, Nagano CP, Carvalho AL, Soares FA. Prognostic value of cell cycle proteins in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity. J Mol Biomark Diagn 2011; 2: 111–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schoelch ML, Regezi JA, Dekker NP et al Cell cycle proteins and the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 1999; 35: 333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ralhan R, Agarwal S, Mathur M, Wasylyk B, Srivastava A. Association between polymorphism in p21(Waf1/Cip1) cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor gene and human oral cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6: 2440–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cox S, Vickers ER, Ghu S, Zoellner H. Salivary arecoline levels during areca nut chewing in human volunteers. J Oral Pathol Med 2010; 39: 465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Effects of arecoline on p21 and p27 in OCSS cells with different cell confluence.

Fig. S2. Inhibition of mTORC1 activity by arecoline.

Fig. S3. (A) Rapamycin (10 nM) was sufficient to downregulate levels of p21 and p27. (B) Relative transcription levels of p21 and p27 after 0.5 mM arecoline treatment for 24 h.

Fig. S4. Independence of PI3K‐Akt signaling on arecoline‐mediated mTORC1 inhibition.

Fig. S5. Independence of AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling on arecoline‐induced downregulation of p21 and p27 in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells.

Fig. S6. Strong inhibition of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) activities by arecoline rather than by areca nut extract (ANE).