Summary

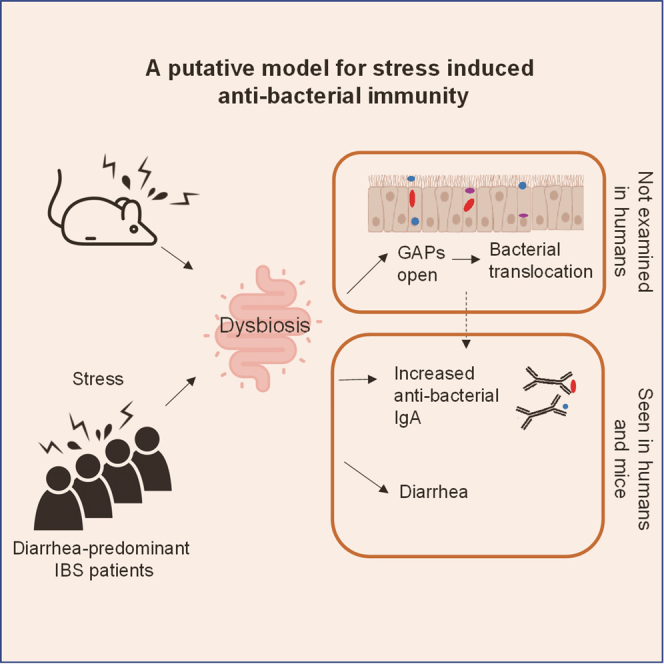

Stress is a known trigger for flares of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); however, this process is not well understood. Here, we find that restraint stress in mice leads to signs of diarrhea, fecal dysbiosis, and a barrier defect via the opening of goblet-cell associated passages. Notably, stress increases host immunity to gut bacteria as assessed by immunoglobulin A (IgA)-bound gut bacteria. Stress-induced microbial changes are necessary and sufficient to elicit these effects. Moreover, similar to mice, many diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) patients from two cohorts display increased antibacterial immunity as assessed by IgA-bound fecal bacteria. This antibacterial IgA response in IBS-D correlates with somatic symptom severity and was distinct from healthy controls or IBD patients. These findings suggest that stress may play an important role in patients with IgA-associated IBS-D by disrupting the intestinal microbial community that alters gastrointestinal function and host immunity to commensal bacteria.

Keywords: stress, host:commensal immunity, IgA, irritable bowel syndrome

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

Stress in mice causes diarrhea, dysbiosis, barrier defect, increased antibacterial IgA

Stress-induced microbial changes are sufficient to elicit the above effects

IBS-D patients from two cohorts display increased and unique antibacterial IgA

Antibacterial IgA in IBS-D correlates with patient symptom severity

Rengarajan et al. show that stress in mice causes fecal dysbiosis, which is sufficient to induce diarrhea, intestinal barrier defect, and increased antibacterial IgA. IBS-D patients also display fecal dysbiosis and increased antibacterial IgA that is unique from healthy or IBD patients. This IgA response correlates with somatic symptom severity.

Introduction

The intestinal tract harbors trillions of commensal bacteria that provide beneficial functions to the host, including nutrient metabolism and protection from infection by pathogenic organisms. The close proximity of these bacteria presents a unique challenge to the immune system, as it must develop appropriately tolerogenic responses against commensal organisms while generating inflammatory reactions against pathogenic bacteria.1, 2, 3 Homeostasis involves peripheral regulatory T (Treg) cells4, 5, 6 and protective immunoglobulin responses7, 8, 9, 10 that react to commensal bacterial antigens. Thus, immune interactions with gut bacteria play an important role in maintaining proper homeostasis and preventing intestinal disease.

Although host genetics and microbial composition are most often thought of as being important for host:commensal interactions, physiologic stress has been hypothesized to play a role in contributing to immune-mediated gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. For example, stress is reported to trigger flares of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).11,12 Murine studies have also supported the notion that stress can affect gut homeostasis. The induction of stress via physical restraint or social stressor exposure has been shown to induce alterations in the gut microbial community and increase susceptibility to intestinal infections.13, 14, 15 Thus, evidence from humans and mice suggests that stress can modulate immune-mediated intestinal disease.

In addition, stress is well established as a potential trigger for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS),16, 17, 18 a common human GI disorder that is characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel patterns. Like IBD, alterations in the intestinal microbiota have been reported in IBS patients.19,20 In fact, a recent report showed that the transfer of fecal microbiota from diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) patients into germ-free (GF) mice leads to the transference of altered gut motility, intestinal barrier dysfunction, and anxiety-like behaviors,21 suggesting that microbial alterations may have mechanistic relevance to some of the symptoms of IBS-D. Thus, IBS-D is a condition associated with stress, microbial changes, and abnormal GI function.

In contrast to IBD, IBS-D occurs in the absence of an overt inflammation or other abnormality seen by intestinal biopsy, radiography, or serum laboratory studies.16,22 Research studies have suggested some alterations in gut immune homeostasis in IBS. For example, a subset of IBS patients display increased intestinal permeability.19,20 Similarly, increases in mast cells and other immune cell populations have also been described in small studies.23,24 Approximately 10% of IBS patients have symptoms following an episode of infectious diarrhea. In these post-infection IBS patients, host gene expression studies from rectal biopsies showed alterations in the pathways of cell junction integrity and general inflammatory response.25,26 Finally, antibodies to vinculin and cytolethal distending toxin B (CdtB) have been reported to be increased in IBS patients.27 However, there exists relatively little evidence for host immune activation against gut bacteria in IBS in comparison to IBD.

Given the reported association of stress with alterations in the gut microbiota, we hypothesized that stress could modulate the host immune response to gut microbes. To test this, we used a murine restraint stress model.28 We found that stress induced alterations in the gut community, signs of diarrhea, translocation of live gut resident bacteria, and evidence of increased immune responses against gut bacteria, with increased immunoglobulin A (IgA) bound to luminal bacteria. Human IBS-D patients exhibited many of the features seen in stressed mice, such as diarrhea and altered microbiota. Notably, a subset of patients showed increased IgA-bound bacteria, which were unique as compared to IgA-bound bacteria of control or IBD patients. In summary, our human and mouse data suggest a model by which stress induces gut community changes that trigger intestinal immune responses and altered GI physiology.

Results

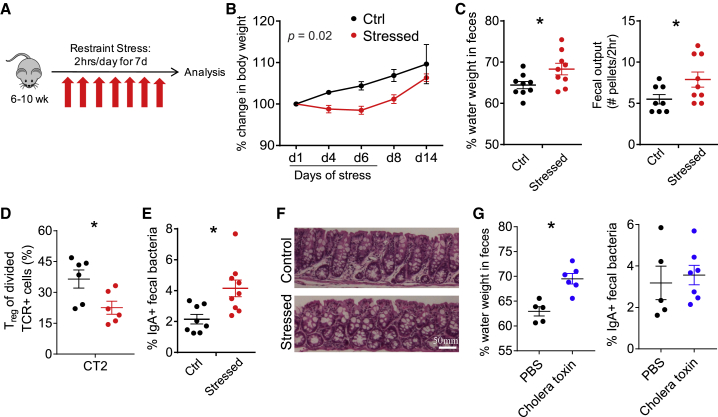

Murine Stress Leads to Alterations in GI Motility and Antibacterial Immunity

To study the effects of stress on the intestinal microbiota and immune system, we used a previously characterized restraint model that does not physically harm the animal and is reported to alter the gut bacterial composition.13,15 This model also induces characteristics of physiologic stress, including increased corticosteroid levels, behavioral alterations in mice, and decreased weight gain.29 As restraint prevents access to food and water, we implemented a 2-h/day restraint period (Figure 1A) to minimize the impact of altered feeding patterns on the microbiota. Consistent with previous studies,30 we observed delayed weight gain during the period of stress (Figure 1B). We also noted that stressed mice had softer stool, consistent with diarrhea, which we quantified by observing an increase in the percentage of water in feces and an increase in fecal pellets output over 2 h (Figure 1C). Thus, this stress model induced alterations in GI physiology with diarrheal features.

Figure 1.

Murine Stress Induces Weight Loss and Features of Diarrhea

(A) Murine restraint stress model. 50 mL conical tubes with airholes were used for restraint for 2 h/day for 7 days. Food and water were withheld from control mice.

(B–F) Effects of stress model.

(B) Body weight (% change, n = 8–9, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA).

(C) GI function: percentage of fecal water weight and number of fecal pellets expelled in 2-h duration on day 8 (n = 8–9).

(D) Peripheral Treg cell induction to Helicobacter. 5 × 104 naive congenically marked CT2 TCR transgenic cells were transferred on day 5 of stress and analyzed 3 days later for the induction of Foxp3IRES-GFP in the cdMLN (n = 6). Mice were stressed for the usual 7 days.

(E) Fraction of IgA-bound fecal bacteria (d8, n = 8-9).

(F) Colon histology. Representative sections from day 8 stressed versus control mice are shown (n = 5).

(G) Cholera toxin-induced diarrhea. Cholera toxin (10 μg) per rectum (p.r.) was administered on days 1 and 4 and analyzed on day 7 for fecal water weight and %IgA+ fecal bacteria (n = 5–7).

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Two to three independent experiments were performed and ∗p < 0.05 using Student’s t test unless otherwise indicated. See also Figure S1.

We next examined whether stress affected the adaptive mucosal immune system. We did not observe marked changes in the frequency of effector CD44hi or Foxp3+ Treg populations in the distal cecum/colon draining mesenteric lymph node (cdMLN) or the more proximal small intestinal draining mesenteric lymph nodes (siMLNs) (Figure S1A). However, there were changes in the development of naive T cells reactive to Helicobacter, a mucosally dominant bacteria in our mice that are continuously exposed to the adaptive immune system.31 The transfer of naive Helicobacter-reactive CT2 T cell receptor (TCR) Tg cells32 on day 5 of stress revealed decreased peripheral Treg (pTreg) cell induction in the cdMLN with stress (Figures 1D and S1B). This decreased conversion did not appear to be due to differences in antigen exposure, as CT2 cells divided to the same degree in both control and stressed animals (Figure S1C). Thus, while the overall proportion of effector to Treg cells appears to be maintained, stress limits peripheral Treg cell generation to at least one commensal bacterial species.

We then assessed the effect of stress on gut B cell responses by analyzing the frequency of intestinal bacteria bound in situ to IgA or IgG via flow cytometry.33, 34, 35 Notably, we observed an increase in the frequency of IgA-bound bacteria in stressed mice (Figures 1E and S1D). This increase was not simply a reflection of increased IgA secretion or accumulation in the feces, as free fecal IgA was unchanged (Figure S1E). The inhibition of pTreg cell selection and increased IgA responses could be secondary to intestinal inflammation. However, we did not observe overt signs of inflammation such as ulceration, edema, or increased mononuclear cell infiltrates by histology (Figure 1F). We did not attempt to elicit immunopathology with further stress, as stress is not thought to directly cause immune-mediated diseases, even though it likely modulates them.16,22 We also asked whether diarrheal-like symptoms that occurred after stress could themselves lead to increased IgA responses to gut bacteria. However, the administration of cholera toxin, which leads to a secretory diarrhea as evidenced by increased fecal water weight (Figure 1G) in the range seen in our stress protocol (Figure 1C), did not markedly increase the frequency of IgA+ fecal bacteria (Figure 1G). Thus, these murine data suggest that stress can induce immune activation to gut bacteria without overt intestinal inflammation.

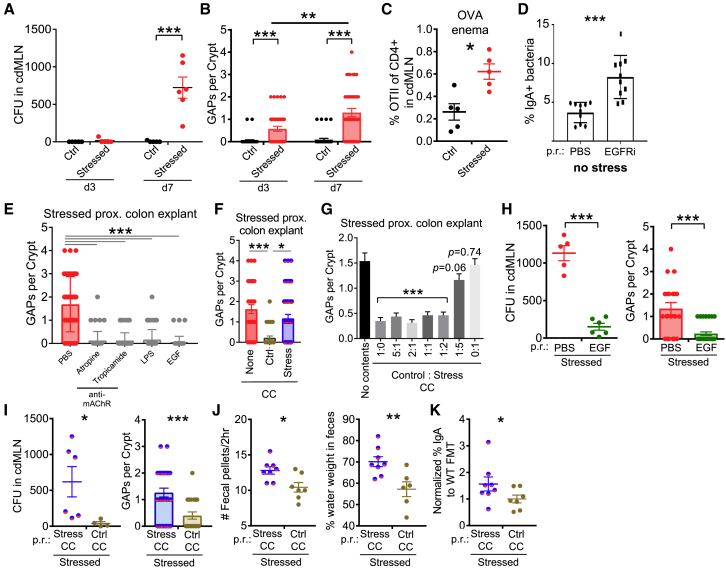

Murine Stress-Induced Dysbiosis Leads to Colonic Barrier Dysfunction through Open Colonic GAPs

The increase in IgA-bound bacteria implied that experimental stress promoted bacterial interactions with the adaptive immune system. This interaction could be mediated by decreased mucosal barrier function, which has previously been reported for murine stress models.36 We therefore tested whether stress could directly lead to bacteria translocating across the mucosal barrier and into the MLNs. Whereas control mice had sterile cdMLNs, we consistently observed 200–1,200 aerobic colony-forming units (CFUs) from stressed mice (Figure 2A). As histology did not suggest a marked barrier breach due to epithelial cell damage after stress (Figure 1F), we evaluated whether colonic goblet cell-associated passages (GAPs) could be a mechanism for bacterial transport across the epithelium.37 Colonic GAPs are normally inhibited by goblet cell-intrinsic Myd88-dependent sensing of the gut microbiota, which suppresses the ability of goblet cells to respond to acetylcholine (ACh), the stimulus driving GAP formation at steady state.38 In stressed mice, colonic GAPs were readily observed by day 3, increasing in frequency by day 7 in the proximal colon (Figure 2B). Open GAPs in the colon have been associated with increased luminal antigen delivery.39 Consistent with this, we observed the increased expansion of OTII cells in response to ovalbumin administered per rectum (p.r.) in stressed mice (Figures 2C and S1F). Furthermore, when GAP formation was induced in the absence of stress using an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (EGFRi),38 there was a significant increase in bacteria targeted by IgA (Figure 2D). Thus, these data show that stress induces GAP formation and bacterial translocation and that in a physiologic state, GAP opening can lead to increased antibacterial IgA.

Figure 2.

Stress-Induced Dysbiosis Leads to GAP-Mediated Bacterial Translocation and Diarrheal Signs

(A) Stress-induced bacterial translocation. Aerobic colony-forming units (CFUs) were assessed in the cdMLN on the indicated days 1 h after stress (n = 4–6).

(B) Stress-induced GAPs. Number of open GAPs per crypt from the proximal colon of stressed mice on the indicated days were assessed by rhodamine-dextran staining (n = 4–6).

(C) Presentation of GAP-dependent luminal antigens to T cells. Naive congenically marked OTII cells (105) were transferred on day 6 of stress, followed by 25 mg ovalbumin p.r. on day 7, and analysis 3 days later for the percentage of OTII cells of all CD4 T cells in cdMLN (n = 5).

(D) Increased IgA+ fecal bacteria in non-stressed mice with open GAPs. GAP formation induced via intraperitoneal EGFRi injection for 7 days and IgA+ fecal bacteria assessed on day 8 (n = 10, 3 experiments).

(E) Closure of GAPs via modulation of ACh/Myd88 pathway. Proximal colon explants, obtained from stressed mice 1 h after the last cycle on day 7, were treated with pan or selective cholinergic antagonists (atropine, tropicamide), LPS, or EGF, and assessed for the number of open GAPs per crypt (n = 4–5).

(F and G) Closure of GAPs ex vivo by control cecal contents (CCs). Colon explants of stressed mice were treated with vehicle, control, or stressed CC (F) or varying ratios of control and stressed CCs (G), and then assessed for GAPs (n = 4–6; Student’s t test comparing different ratios to vehicle treatment).

(H) EGF rescues GAP opening and bacterial translocation during stress. EGF was administered p.r. to mice after 2 h of stress every day, and on day 8 bacterial translocation (CFUs in cdMLN) and open GAPs in proximal colon explants were assessed (n = 5–6, 2 expts).

(I–K) Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) partially rescues the effects of stress. Stressed mice were given repeated FMT p.r. of either stressed or control CCs daily after each stress cycle and assessed for the following (n = 6–8): (I) bacterial translocation by CFUs in cdMLN and number of open GAPs in proximal colon assessed 1–2 h after the last day of stress on day 7; (J) diarrhea signs by number of fecal pellets expelled during the 2-h stress cycle (average of days 6 and 7) and percentage of fecal water weight assessed on day 7 before stress; and (K) frequency of IgA+ bacteria normalized to each experiment’s control FMT average assessed on day 7 before stress.

The data are presented as means ± SEMs and Student’s t test. Two to three independent experiments for all of the panels. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, and ∗∗∗p < 0.0005.

We next sought to understand how stress may lead to the opening of colonic GAPs. Using colon tissue explants from stressed mice, we found that blockade of the ACh pathway using muscarinic AChR antagonists led to GAP closure (Figure 2E). In addition, GAPs could also be closed via the activation of the EGFR, either directly via EGF or indirectly by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced MyD88 signaling, which inhibits responses to ACh in goblet cells to form GAPs.38 These findings suggested that the open GAPs in stressed mice could still be inhibited normally by the MyD88 bacterial sensing pathway, leading to the hypothesis that stressed microbiota is unable to close colonic GAPs. Using ex vivo explants of colonic segments from stressed mice as described above, we found that cecal contents (CC) collected from control mice closed GAPs, whereas CC from day 7 stressed mice were ineffective (Figure 2F). A 1:2 mixture of control and stressed CC was still capable of closing GAPs (Figure 2G), suggesting that stressed CC did not contain signals that dominantly opens GAPs, but rather are missing signals that close GAPs. To assess whether the ACh/MyD88 pathway for GAPs was operant in vivo with stress, we performed intra-rectal administration of EGF after every stress period. EGF treatment inhibited GAP formation and reduced bacterial translocation to the cdMLN (Figure 2H). Thus, these data suggest that stress directly or indirectly leads to a loss of luminal signals that normally mediate GAP closure, resulting in bacterial translocation.

We then assessed whether cecal contents from non-stressed mice were directly involved in GAP formation in vivo. We administered CC p.r. daily immediately after each stress. Notably, stressed mice receiving CC from non-stressed control donors showed fewer open GAPs and lower levels of bacterial translocation to the cdMLN (Figure 2I), suggesting that microbial changes and not increased ACh signaling with stress40 may be the dominant factor leading to open GAPs in stressed mice. Stressed mice receiving CC from control mice also displayed a decreased frequency of IgA-targeted bacteria and diarrhea features suggested by a lower fecal water weight and fecal output (Figures 2J and 2K). Thus, these data suggest that the microbial dysbiosis that arises during stress leads to open GAPs and bacterial translocation, which provides a potential mechanism to explain the increased immune responses to gut bacteria.

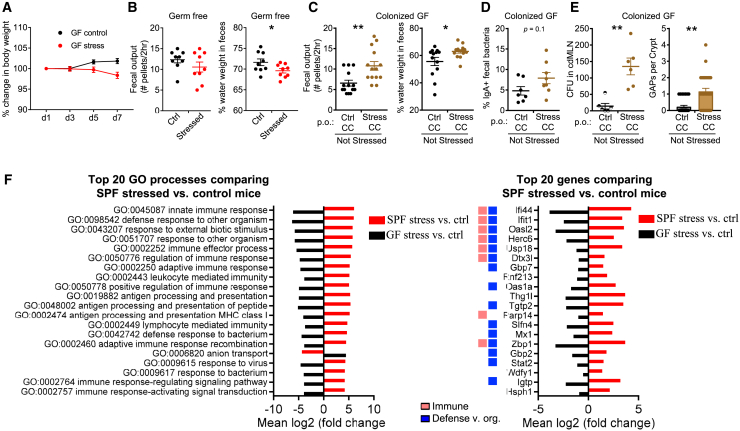

Transplant of Stressed Microbiota Is Sufficient to Increase Antibacterial Immunity and Alter Gut Function

The above data suggested that the effects of stress in the gut are largely mediated by the microbiome. To directly confirm this, we stressed GF mice, which are reported to have an exaggerated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to restraint stress.41 Stressed GF mice exhibited a systemic physiological change to stress as assessed by weight loss, albeit slower than specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice (Figure 3A). Notably, GI features of diarrhea such as increased fecal water weight and fecal output were not observed; instead stressed mice actually exhibited decreased fecal water weight (Figure 3B). Thus, the presence of commensal bacteria is essential to observe the diarrheal effects of stress.

Figure 3.

Dysbiosis Induced by Stress Drives Intestinal and Immunological Alterations

(A and B) Effect of stress on germ-free (GF) mice. Stressed GF mice were assessed for the following: (A) change in body weight (n = 5, 1 expt.) and (B) GI function assessed by the number of fecal pellets expelled in a 2-h duration and percentage of fecal water weight on day 8 (n = 10, 2 expts.).

(C–E) Microbiota are sufficient to induce features of stress. GF mice were transplanted via oral gavage with stressed or control CCs without concurrent stress and assessed 7 days later for the following: (C) number of fecal pellets expelled in a 2-h duration and percentage of fecal water weight (n = 13, 2 expts); (D) percentage of IgA-bound fecal bacteria (n = 7–8, 2 expts); and (E) number of GAPs per crypt in the proximal colon and CFUs in cdMLN (n = 8–13, 1 expt).

(F) Stress-induced biological processes in the colon. GF and SPF mice were stressed for 7 days. The following day, the entire colon and cecum with respective unstressed controls was analyzed by RNA-seq (n = 3/group, 1 expt). The top 20 Gene Ontology processes created with Pathview with GAGE padj < 0.05 comparing SPF stressed versus control mice were chosen for display in red. The fold change for the same pathways (padj < 0.05) in GF stressed versus control mice is displayed for comparison (black). The top 20 most significant genes (padj < 0.05) that were upregulated or downregulated in SPF stressed versus control mice, with colors indicating the Gene Ontology processes categories in legend. All of the pathways with the category designations and involved genes can be found in Data S2.

The data are presented as means ± SEMs, Student’s t test, and 2–3 independent experiments for all of the panels unless otherwise specified. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, and ∗∗∗p < 0.0005. See also Figures S2 and S3.

The effect of dysbiosis on the gut could be dependent on neuroendocrine effects of stress such as the induction of ACh,42 which can also lead to opening of GAPs.38 To test whether dysbiosis alone is sufficient, we performed fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) of stressed or control fecal microbiota into GF mice without any concurrent restraint stress. Compared to GF mice that received control CC, mice that received stressed CC displayed diarrheal features with increased fecal water weight and fecal output on day 7 after the FMT (Figure 3C). Stressed FMT mice also displayed a trend toward increased fecal antibacteria IgA (Figure 3D). Notably, microbiota from stressed, as compared to control, mice were not as efficient at closing colonic GAPs generally open in GF mice,38 allowing more bacterial translocation (Figure 3E). Dysbiotic microbiota from stressed mice alone is therefore sufficient to phenocopy a number of features of stress when introduced into GF mice. In total, these data suggest a model in which stress induces gut microbial dysbiosis, which in turn triggers altered gut motility, altered antibacterial immunity, and colonic barrier alterations.

We further probed the role of the intestinal microbiome in the response of the host to stress through a global analysis of host gene transcription in colonic tissues during stress in SPF and GF mice. In SPF mice, stress induces an increase in transcriptional pathways involved in innate and adaptive immunity and defense against organisms when compared with control SPF or GF mice (Figures 3F and S3). In contrast, stress in GF mice compared to non-stressed GF mice leads to the significant downregulation of the same immune and defense pathways (Figures 3F and S3A). These pathways included cytokine responses (Ifi44, Ifit1, Gbp7, Ifit3, and Ifit3b), antigen processing (Rnf213), and microbial defense (Parp14 and Slfn4) (Figure 3F). Although we do not examine this issue further, stress is correlated with decreased GO:anion transport in SPF mice (Figures 3F and S3B), which we speculate results in decreased water resorption and increased fecal water. Conversely, stress in GF mice increases anion transport, which is correlated with decreased fecal water weight (Figure 3B). These results suggest that the microbiota is crucial in driving gut immune responses during stress.

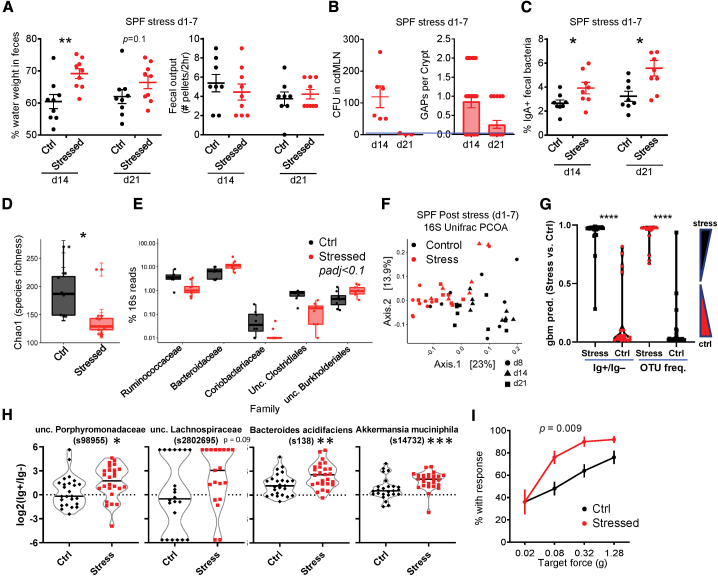

Persistence of Bacterial Dysbiosis after Stress

These data suggested a model by which physiologic stress alters the microbiota that acutely leads to GAP opening, enhanced adaptive immune responses, and features of diarrhea. We then asked whether these biological effects persisted beyond the period of stress. While fecal output normalized by 7 days after the last stress period (day 14), fecal water weight was still increased until day 14 post-stress (day 21; Figure 4A). Bacterial translocation occurred 7 days after stress (day 14), but resolved by day 21, which correlated with the closing of GAPs (Figure 4B). Notably, the increase in IgA-targeted bacteria persisted 14 days after stress (day 21; Figure 4C). Thus, the effects of stress on the mucosal immune system and GI function persist after stress is removed.

Figure 4.

The Effects of Stress on the Microbiota and Host Immunity Persist

(A–C) Persistent effects of stress. SPF mice stressed daily on days 1–7 as per Figure 1A were assessed on days 14 and 21 for the following: (A) percentage of fecal water weight and number of fecal pellets expelled in a 2-h duration (n = 8–9); (B) number of GAPs (n = 3–6) and bacterial translocation to the cdMLN (n = 3–6); and (C) frequency of IgA-bound bacteria (n = 8).

(D–F) Dysbiosis in stressed mice. Fecal pellet 16S rRNA was sequenced and analyzed for day 8 stress versus control mice (n = 8–9). (D) Chao1 alpha diversity index and (E) differentially enriched (Mann-Whitney U padj < 0.1) bacterial families. Boxes indicate the first and third quartiles (25th to 75th percentiles) and the whiskers extend from the box hinge to the largest or smallest value no further than 1.5∗interquartile range (IQR). (F) PCoA plots on unweighted Unifrac distance of microbial composition from 16S rRNA sequences from stress and control mice at days 8, 14, and 21 (n = 8–9).

(G) Machine learning prediction using OTU frequency versus IgA enrichment ratio. A gradient boosted model (GBM, see Method Details) was generated on a random 75% of the dataset (OTU frequency or IgA ratio for all days: 8, 14, and 21) and tested on the remaining 25%. The data shown are the average prediction values of 160 runs, or 40/sample (25%). The IgA ratio (IgA+/IgA−) is calculated as log2(%IgA+/%IgA−) (see Method Details). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s (n = 24–28).

(H) IgA-enriched OTUs after stress. OTUs are selected based on being IgA enriched by both DESeq2 and LEfSe analysis (see Figure S4B) using data for all days (Mann-Whitney U; n = 24–28; samples with 0 in IgA+ and IgA− subsets not plotted).

(I) Stress-induced abdominal hypersensitivity. Shown are the percentage of mice with response for each von Frey filament at the indicated target forces on day 8 (n = 10 males), 2-way ANOVA p value.

Student’s t test was used unless otherwise indicated and 2–3 independent experiments for all of the panels unless otherwise specified. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, and ∗∗∗p < 0.0005. See also Figure S4.

As the effect of stress on the GI tract was dependent on the microbiota, we analyzed the changes in taxonomy by 16S rRNA sequencing (rRNA-seq).43 We observed that 7 days of stress leads to significant decreases in species richness, a component of alpha diversity (Figure 4D), as well as overall microbial composition, with an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes families (Figure 4E; PERMANOVA = 0.001). These changes were consistent with previous work using different periods of restraint stress.13 Notably, these changes in bacterial composition persisted after the period of stress (Figures 4F and S4A).

We also examined whether the IgA+ bacteria fraction changed during stress. We therefore used gradient boosted modeling (GBM, see Method Details) to ask whether IgA enrichment can predict stress as the experimental variable. Analysis of the combined data from all three time points (days 8, 14, and 21) using GBM revealed that the effect of stress had a clearly discernable effect on operational taxonomic unit (OTU) frequency (i.e., dysbiosis), or IgA enrichment (log2 (% OTU in IgA+/% in IgA−)) (Figure 4G).

Examination of individual OTUs that were different between the IgA+ and IgA− 16S rRNA-seq data by both DESeq2 and LEfSe analyses35 revealed several OTUs that showed increased IgA binding with stress—particularly, Akkermansia mucinophila (Figures 4H and S4B). In summary, these 16S rRNA data support the model that stress in mice leads to alteration in the microbiota, which is associated with changes in immunity to gut bacteria.

IBS-D Patients, Like Stressed Mice, Often Have Increased IgA+ Bacteria

Although caution should be exercised in extrapolating results in mice to humans, we noted that the murine stress model exhibits many features of IBS-D, with increased fecal water weight and fecal output (Figure 1C), microbial changes (Figures 4D–4F), and a lack of overt features of inflammation on histology (Figure 1F).16,22 We also observed that stressed mice demonstrated abdominal hyperalgesia to von Frey filament application (Figure 4I), which may be equivalent to the increased visceral hypersensitivity described in IBS patients. These data suggest that experimental stress in mice can induce phenotypic somatosensory and GI effects reminiscent of human IBS-D.

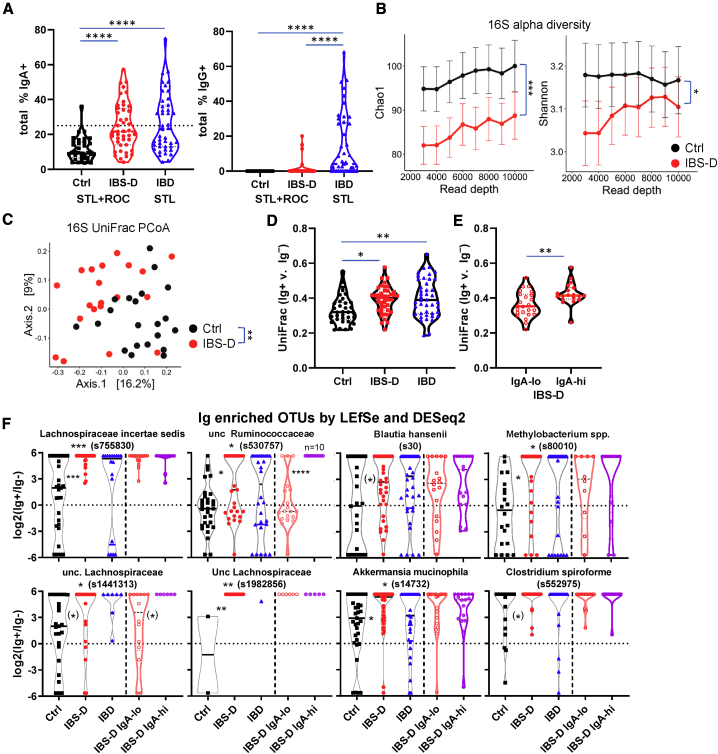

In view of these similarities, we asked whether IBS-D patients also demonstrated altered antibacterial IgA responses similar to those observed in stressed mice. Enhanced IgA and IgG binding to fecal bacterial has been reported for IBD.33,35 We analyzed IgA binding to fecal bacteria by flow cytometry from IBS-D patients compared to age, gender, and geographically matched healthy controls (Ctrl) from two geographical cohorts, St. Louis, Missouri (STL) and Rochester, Minnesota (ROC).44

Notably, IBS-D patients displayed significantly higher IgA-bound fecal bacteria than healthy individuals (Figure 5A), as well as patients with intestinal (celiac sprue) and non-intestinal (rheumatoid arthritis) immune disorders (Figure S5A). The STL and ROC cohorts exhibited similar distributions of IgA-bound bacteria (Figure S5B), suggesting that enhanced IgA targeting is not dependent on geographic location. More important, these data show that the enhanced IgA response in IBS-D is reproducible between two different medical centers, which can be a major issue, given the reliance on symptom-based criteria to make the diagnosis of IBS.45 In addition to IgA-bound bacteria, IBS-D patients showed increased free fecal IgA (Figure S5C). Notably, IBS-D patients showed a non-significant decrease in the frequency of IgA-bound bacteria, but very little to no IgG-bound bacteria compared to IBD patients (data from Rengarajan et al.35) (Figure 5A). We hypothesize that these differences are due to the lack of overt inflammation and frank mucosal barrier breaches in IBS-D patients, which would permit IgG to access the intestinal lumen.35 While our work was under review, a study from China was published that also showed increased IgA-bound bacteria in IBS-D patients compared to control.46 Thus, these data confirm an enhanced intestinal immune response to commensal bacteria in a subset of IBS-D patients reminiscent of that seen in stressed mice.

Figure 5.

IBS-D Patients Show Fecal Dysbiosis and Increased Ig Responses to Fecal Bacteria

(A–F) Fecal samples from patient cohorts from St. Louis (STL) and Rochester (ROC) were analyzed by flow and 16S rRNA sequencing (Ctrl = 34, IBS-D = 43, IBD = 43).

(A) Increased IgA-bound bacteria in IBS-D. Percentage of IgA- and IgG-bound fecal bacteria seen by flow cytometry (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test). Each dot represents a fecal specimen from one patient.

(B) Decreased microbial diversity in IBS-D. Chao1 alpha diversity index (means ± SEM). Chao1 p value calculated with mixed effects testing with read depth as the random effect.

(C) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plots on Unifrac distance of microbial composition for Ctrl and IBS-D.

(D and E) Greater differences in IgA-bound versus unbound bacteria in IBS-D. Unifrac distances between IgA+ and IgA− 16S rRNA sequencing for each patient is shown in (D) (ANOVA with Tukey’s) and for IgA-hi/lo subsets of IBS-D in (E) (Student’s t test; IgA-lo = 24, IgA-hi = 19).

(F) IgA-enriched OTUs in IBS-D. OTUs are selected based on being IgA enriched by both DESeq2 and LEfSe analysis. See also Figures S5F and S5G. Note that the samples with 0 in IgA+ and IgA− subsets are not plotted.

Kruskal Wallis with Dunn’s test, and in parentheses, Mann-Whitney U between Ctrl and IBS-D; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, and ∗∗∗p < 0.0005. Each experiment on each patient performed once. See also Figure S5.

IBS-D Patients Show Altered IgA Responses to Fecal Bacteria

Consistent with prior reports,21,47 we observed bacterial alterations in STL IBS-D patients compared with controls, as assessed by both a decrease in alpha diversity and changes in compositional beta diversity based on principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of UniFrac distances between individuals (PERMANOVA p < 0.001 for both) (Figure 5B and 5C). We observed a decrease in several families belonging to the Firmicutes phylum (unclassified [unc.] Clostridiales, unc. Firmicutes, and Erysipelotrichaceae) and an increase in one belonging to the Bacteroidetes phylum (Porphyromonadaceae) (Figure S5D). Interestingly, a similar contraction of Firmicutes and expansion of Bacteroidetes was also observed in our stressed animals (Figure 4E). Thus, IBS-D patients exhibit microbial differences compared to healthy individuals, which in some cases, corresponded with taxonomic differences observed in stressed animals.

We next asked whether there were differences in the Ig-bound (IgA or IgG) versus unbound bacterial in IBS-D patients (STL + ROC). Analysis of Renyi entropy, an assessment of alpha diversity, revealed that IBS-D patients exhibited decreased diversity in both the Ig-bound and unbound fractions (Figure S5E), similar to that seen with the analysis of the total input 16S rRNA-seq (Figure 5B). Comparison of the UniFrac distances between an individual’s Ig+ versus Ig− microbial populations revealed significant increases in IBS-D or IBD patients compared with control patients (Figure 5D), suggesting that these diseases are associated with Ig specific to certain taxa, leading to greater differences between the Ig-bound and unbound fractions. Consistent with this hypothesis, the Unifrac distance between an individual’s Ig+ versus Ig− fractions varied by the IgA+-bound frequency. IgA-hi IBS-D patients, which we classified at >25% based on the control population (Figure 5A, mean + 2× SD), showed significant increases in the Unifrac distance between Ig+ and Ig− fractions compared with the IgA-lo IBS-D patients (Figures 5E and S5F). Notably, the IgA-lo IBS-D subset was not clearly distinguishable from control patients by this metric (Figure 5D versus Figure 5E). Thus, these data suggest that IBS-D patients, and in particular those with an IgA-hi phenotype, show altered Ig targeting of specific bacteria.

To determine the OTUs that were enriched in the Ig+ subset in control or IBS-D (STL + ROC) patients, we compared the Ig+ and Ig− 16S rRNA-seq data per group using LEfSe and DESeq2. We focused on the intersection of these Ig-enriched OTUs with both methods using the reasoning that they would represent the most reliably Ig-enriched OTUs (Figure S5G). Many of these OTUs were Ig enriched in both control and IBS-D patients (Figures S5G and S5H), as expected based on previous results in other patient groups.33, 34, 35 However, there were a number of OTUs specifically Ig enriched in IBS-D versus control patients, including 6 from the Clostridiales order (Figure 5F; Lachnospiraceae, Clostridium, Blautia, and Ruminococcaceae), of which 4 are Lachnospiraceae (including Blautia). Subgroup analysis of IBS-D IgA-hi and IgA-lo (Figure S5G) revealed that 2 OTUs, in particular an unc. Ruminococcaceae, were preferentially Ig enriched in the IgA-hi subgroup (Figure 5F; 2nd in top row, 1st in bottom row). However, these IgA-enriched OTUs in our IBS-D patients were not related to taxa identified by Liu et al.46 of genus Escherichia-shigella, Granulicatella, and Haemophilus (Figure S5I). This may be attributed to differences between the studies related to our use of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) versus magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS),46 as well as the geography of the patient cohorts affecting diet and genetics.

Notably, the IgA-enriched OTUs by LEfSe/DESeq2 showed no overlap between IBS-D (Figure S5G) and IBD35 if the OTUs IgA enriched in controls were excluded. Two taxa were increased in IgA targeting in both murine stress and human IBS-D: Verrucomicrobiaceae (genus Akkermansia) and Lachnospiraceae (genus unc. and Blautia) (Figures 4H and 5F). Thus, these OTU level analyses suggest that IBS-D is associated with a specific Ig response against bacterial taxa that is different than that seen in control or IBD patients and with some overlap with murine stress model.

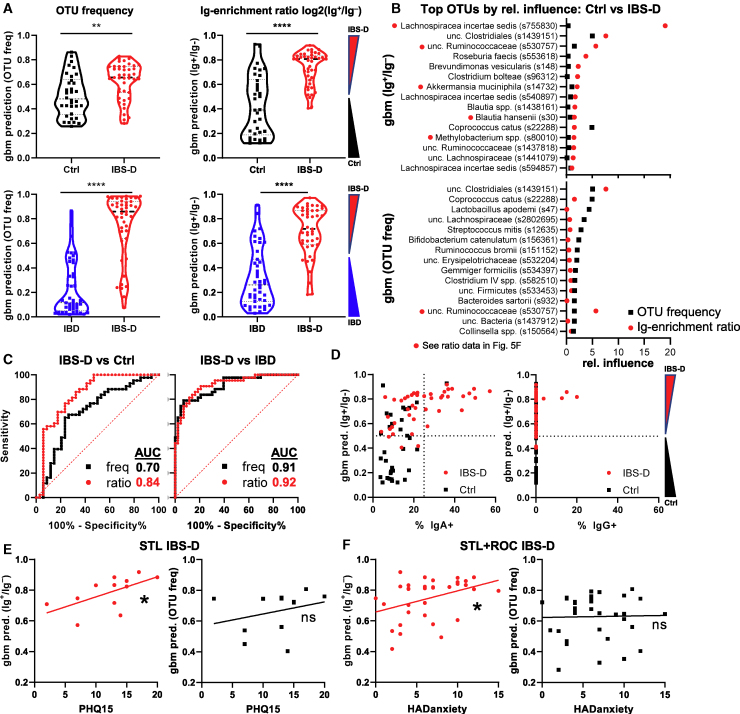

IgA Antibacterial Immunity Is Better than Dysbiosis as a Predictor of IBS-D

After finding differences between IBS-D and controls in the microbial communities and the host:commensal response (Figures 5A and 5D–5F), we sought to understand whether individual OTUs or taxa have a predictive ability in delineating clinical populations. Anticipated limitations to this approach included the realization that this approach would not be applicable to individuals that do not harbor the bacteria, an important issue in the human population. Moreover, analysis of OTUs individually would not reveal coordinated Ig responses within a patient against a set of bacteria. We therefore turned to machine learning to test whether Ig enrichment can be used to predict disease. As discussed above, we used GBM to generate prediction values for binomial outcomes, which range from 0 to 1 for a given comparison, with values closer to 0 or 1 representing a greater “confidence” of prediction (i.e., control versus IBS-D).

We assessed the ability of GBM to distinguish between IBS-D and control patients using OTU frequency or Ig-enrichment ratios (log2(% Ig+/% Ig−); see Method Details). While it was clear that the distribution of GBM prediction values were statistically different between diseases, there was a substantial overlap when OTU frequency values (i.e., analysis for dysbiosis) were used (Figures 6A, upper left, and S6A). By contrast, prediction values based on Ig-enrichment ratios were more distinct, allowing for clearer separation between control and IBS-D patients (Figure 6A, upper right). It is notable that a subset of control patients have predictions that overlap with those from IBS-D patients, which is consistent with the potential for underreporting IBS in the general population, the known mechanistic and clinical heterogeneity of IBS-D, and the lack of objective testing to establish a diagnosis of IBS-D.16,22 A difference between IBS-D and control patients was also seen when dada2 amplicon sequence variant (ASV) data were used (Figure S6B). Interestingly, the clustering of ASVs improved GBM discrimination between IBS-D and control, suggesting that closely related 16S rRNA ASVs behaved similarly (Figure S6B). Thus, these data suggest that there are clearly discernable features of Ig-enriched bacteria in IBS-D patients as compared to control patients.

Figure 6.

Predictive Value of IgA Response for IBS-D

(A–F) Machine learning (GBM) evaluation of IBS-D using OTU frequency versus Ig ratio data (see Method Details) using data from Figure 5.

(A) Average prediction values for OTU frequency and Ig-enrichment ratios for Ctrl versus IBS-D, and IBS-D versus IBD (Student’s t test). Note that Ig enrichment is used as IBD patients have IgG+IgA− bacteria.

(B) OTUs with the greatest relative influence differ between GBM modeling using OTU frequency versus Ig ratios. Average relative influence values are shown for Ctrl versus IBS-D comparisons with the indicated dataset. The red dots by the OTU name indicate bacteria identified as IgA enriched (Figure 5F).

(C) IgA ratios have a higher area under the curve (AUC) than the OTU frequency for predicting IBS-D versus Ctrl. AUC curves are shown for the indicated comparisons between patient groups using the OTU frequency or Ig ratio data.

(D) Association of IgA frequency with correct disease prediction. GBM prediction values are plotted against IgA/G-bound bacterial percentage.

(E) Correlation of IBS-D prediction with PHQ-15 and HADS anxiety scores. Linear regression analysis of PHQ-15 (subset of STL, n = 12 patients who returned survey) or HADS anxiety (STL + ROC, n = 12 + 22 patients who returned survey) scores versus GBM prediction values from OTU frequency or IgA ratios is shown.

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.00005. Each experiment on each patient performed once. See also Figures S6 and S7.

The OTUs that formed the basis of these predictions (relative influence) mostly differed between OTU frequency versus Ig-enrichment ratios, with only 3 OTUs shared among the top 15 for relative influence (Figure 6B). Many of the OTUs exerting the highest relative influence for Ig enrichment (Figure 6B; red dots by taxonomy) were also seen by direct comparisons of Ig+ versus Ig− OTU frequencies using LEfSe/DESeq2 (Figure 5F). Moreover, Ig-enrichment ratios reveal more distinct changes between IBS-D and control patients than analysis of dysbiosis using OTU frequency, with a substantially higher area under the curve (AUC; 0.84 versus 0.7, respectively; Figure 6C). Lastly, the frequency of IgA+ and IgG+ bacteria in the feces was clearly associated with stronger IBS-D prediction values, as only IBS-D patients with normal frequencies of Ig-bound bacteria would be classified as control patients by GBM (Figure 6D). The correlation between Ig-bound bacterial frequency and the ability of GBM to predict IBS-D using Ig-enrichment ratios further supports the notion that host:commensal immunity is altered in IBS-D. These data therefore suggest that Ig-enrichment ratios can offer a different perspective on host:commensal interactions independent of assessments of dysbiosis using OTU frequency.

Clear Differences in Bacterial Composition and Ig Reactivity between IBS-D and IBD

By contrast, IBS-D was easily distinguished from IBD using OTU frequency as well as Ig-enrichment ratios (Figure 6A, bottom). The OTUs with highest relative influence in this model differ from control versus IBS-D analysis, consistent with the notion that these are distinct disease entities (Figure S6C). However, there was a small subset of IBS-D patients who appeared to be classified as IBD based on OTU frequency and/or Ig enrichment (Figures 6A and S6D). It is currently unclear whether this is due to the known set of IBD patients who are thought to have concurrent IBS,48,49 thus affecting our prediction modeling algorithm, a pre-disease state (antibody without overt disease),50 and/or normal heterogeneity among IBS-D patients such that some have Ig enrichment and/or dysbiosis consistent with IBD, and vice versa. However, the vast majority of IBS-D and IBD patients exhibit clearly distinguishing features in OTU frequency and Ig enrichment, with AUC both >0.9 (Figure 6C). In summary, these data suggest that the dysbiosis and the targets of the antibacterial B cell response in IBD is distinct from that seen in IBS-D.

Association of Host:Commensal Immunity with Stress in IBS-D

Since our murine studies suggested that stress-induced dysbiosis can lead to increase IgA-bound bacteria and induce signs of diarrhea—all features observed in IBS-D patients—we asked whether we could quantify stress in humans and correlate that with features of IBS-D. We noted that the assessment of somatization (Patient Health Questionnaire-15 [PHQ-15], STL, n = 12 patients who returned the survey) or anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] anxiety, STL + ROC, n = 12 and 22 patients, respectively, who returned the survey) correlated with the GBM prediction value for IBS-D derived from Ig-enrichment ratios but not OTU frequency (Figures 6E and 6F). This correlation was not seen with a measure of depression (HADS depression, STL + ROC, n = 12 and 18, respectively) or symptom severity score (SSscore, STL + ROC, n = 14 and 19, respectively) (Figure S7A). Antidepressant use was associated with stronger IBS-D GBM prediction values (Figure S7B). There were too few cases of post-infectious IBS-D for interpretation (Figure S7C). However, there was no clear association of age, body mass index (BMI), or year of diagnosis with GBM prediction (Figures S7C and S7D). Nonetheless, the data from IBS-D patients show notable parallels with experimental stress in mice and support the model that stress can lead to alterations in gut bacteria and host homeostasis, physiology, and immunity.

Discussion

These data from both murine models and human disease suggest that physiologic stress can alter intestinal host:commensal homeostasis and immunity. First, we observed that a murine stress model can induce significant changes in the microbiota. Dysbiosis is also seen in IBS-D, a syndrome associated with stress. Second, stress-induced dysbiosis in mice is sufficient to induce signs of diarrhea. Bacteria from IBS-D patients have also been shown to induce features of IBS-D when transferred into mice.21 Third, stress-induced dysbiosis in mice triggered the development of bacterial translocation via GAPs and increased IgA responses to commensal bacteria. IBS-D patients also exhibited increased IgA responses compared with control patients. Finally, stress in mice induced an antigen-specific immune response in a select group of commensal bacteria. IBS-D patients also exhibited increased IgA responses to bacteria in related taxa. Although IBD also shows increased IgA-bound bacteria, the taxa targeted by IBS-D is mostly distinct from that of IBD, suggesting a different pathophysiology. Notably, the anticommensal IgA response was a better predictor of IBS-D than bacterial frequency and was better correlated with surrogate indicators of widespread pain experiences and anxiety.

Using a murine restraint model, we showed that stress induces dysbiosis and bacterial translocation. These data are consistent with prior publications on the microbiota13,51 and bacterial translocation,36,52,53 although it is notable that markedly longer periods of stress—up to 8 h/day—were used than the 2 h used in our study. We link these observations together by showing that stress-induced dysbiosis leads to the opening of GAPs, a mechanism that is well established to result in bacterial translocation and an enhancement of adaptive immune responses to luminal substances. While our data suggest that dysbiosis itself is sufficient to induce these changes, it remains probable that stress contributes to alterations in gut homeostasis via direct effects on the nervous system, neuromodulators such as ACh, which could affect gut motility, hypersensitivity, or permeability,54, 55, 56 and immunomodulators such as corticosteroids, which could affect immunity and inhibit bacterial killing.57 In addition, it is unknown whether GAPs open during human stress or in human IBS-D, and if so, how long after the period of stress, or whether they are associated with symptoms. Finally, it is not clear whether these enhanced immune responses in IBS-D directly contribute to GI dysfunction as in IBD or represent a response to it. Thus, much remains to be discovered regarding the mechanisms by which stress disrupts host:commensal homeostasis leading to dysbiosis, bacterial translocation, and altered antibacterial immunity.

An unexpected observation of this study was that stress could induce easily detectable immunologic changes as measured by IgA bound to fecal bacteria in mice. Moreover, IgA-bound bacteria was clearly elevated in almost half of our IBS-D patients and was consistent with a study by Liu et al.46 Antibacterial IgA responses in IBS-D were further supported by the machine learning analysis of fecal IgA-enriched bacterial OTUs. These metrics showed a 0.82 and 0.84 AUC for %IgA and machine learning, respectively, in the comparison between IBS-D and control patients. This is in line with other biomarker studies in IBS, including antibodies to CdtB and vinculin (AUC 0.81)58 and performed better than fecal microbial analysis in one study (AUC 0.74).59 We speculate that the subset of patients associated with enhanced IgA+ frequency and/or altered IgA-bound bacteria by machine learning represents a distinct IBS-D subset with stress-induced immunity to gut bacteria. We predict that these IgA-associated IBS-D patients may exhibit differential responsiveness to treatment such as antimicrobial therapy22 that may decrease the microbial stimulation of the immune system. Future clinical studies with larger cohorts and multiple medical centers will be required to confirm these results and determine whether this subset of IgA-associated IBS-D patients overlap with those expressing anti-CdtB/vinculin antibodies or exhibit a different pathophysiology, and whether this may be useful for directing clinical therapy.

The increase in IgA binding to bacteria in IBS-D or murine stress was also associated with changes in the taxa targeted by the adaptive immune system. This included taxa from several different families, some of which were shared between mouse and human. One of these bacteria, A. mucinophila, is notable as it has been reported to facilitate tumor immunotherapy in murine cancer models.60 Akkermansia was also shown to induce adaptive effector T cell and IgG1 responses during homeostasis in mice.61 It is intriguing to speculate that this species may exhibit continual host:commensal interactions that could be altered by stress. Alterations in the T and B cell immune response to Akkermansia may then have prolonged effects on gut homeostasis and physiology.

In addition to IBS-D, stress has been associated with disease activity in IBD.11,62 However, we observed little overlap between the IgA-targeted bacteria in IBS-D and IBD. This would be consistent with the marked differences in pathophysiology, as only IBD is associated with frank mucosal inflammation. Nonetheless, it may be speculated that the effect of stress on increased bacterial translocation and immunity seen in mice may be exacerbated pathogenic antibacterial immune responses in human IBD patients. Thus, these data may be useful to reframe the discussion of the effects of stress and somatization on the body to include the potential for microbiota-driven physiologic and immunologic effects that may break homeostasis in not only IBS-D but also IBD and other autoimmune diseases that may be affected by the gut microbiota.63,64

Limitations of the Study

In this study, we use a stressor in mice that appears to phenocopy human IBS-D. However, we cannot be certain that this model recapitulates the human experience. First, we acknowledge that the diarrheal phenotype observed may be modest, but it is unknown whether increasing stress would more faithfully mimic human disease. Second, while both human IBS-D patients and stressed mice exhibit dysbiosis, the mechanisms by which this occurs may differ and this is not addressed by this study. Third, while fecal transplant of stressed microbiota into GF mice can recapitulate many of the effects of stress in mice on our measured parameters, we did not test for increased visceral hypersensitivity, which may be similar to the increased anxiety-like behavior seen in mice transplanted with human IBS-D microbiota.21 Finally, while GAPs likely play a role in immune activation during murine stress, it is unclear the extent GAPs contribute to GI dysfunction in mice, and whether GAPs are involved in human IBS-D. Thus, while the murine model provides proof of principle that stress can induce features of IBS-D, caution must be exercised in making causal claims to human disease.

Our human studies were performed on a relatively small number of patients, limiting our ability to generalize these results. Although the increased frequency of IgA+ bacteria in IBS-D was supported by another study from China,33 the IgA-targeted taxa appeared to differ. Another unresolved question is whether stress/anxiety itself is sufficient to trigger increased IgA-bound bacteria without IBS-D symptoms. Finally, the immune changes in IBS-D as reflected by IgA-bound bacteria clearly occur in a subset of patients, but their impact on triggering or maintaining the symptoms of IBS-D remains unclear. Thus, future studies are required to address these questions on the role of stress on host:commensal immunity and GI function.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CD4 BV711 | Biolegend | Cat#100550 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.1 A700 | Biolegend | Cat#110724 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.2 PE | Biolegend | Cat#109807 |

| Anti-mouse CD25 APC | Biolegend | Cat#102012 |

| Anti-mouse CD62L APC-Cy7 | Biolegend | Cat#104428 |

| Anti-mouse CD44 BV605 | Biolegend | Cat#103047 |

| Anti-mouse TCR Va2 APC-Cy7 | Biolegend | Cat#127818 |

| Anti-mouse CD25 PerCP-Cy5.5 | Biolegend | Cat#102030 |

| Anti-mouse CD44 AF430 | Biolegend | Cat#103047 |

| Anti-mouse Thy1.1 PECy7 | Biolegend | Cat#105326 |

| Goat IgG FITC isotype control | Abcam | Cat#37374 |

| Goat anti-human IgA Dylight 650 | Abcam | Cat#98556 |

| Goat anti-human IgG PE | Abcam | Cat#98596 |

| Cell trace violet cell proliferation kit | Invitrogen | Cat#34557 |

| ELISA Goat anti-human kappa IgA | Southern Biotech | Cat# SB 2061-01 |

| ELISA IgA standard | Southern Biotech | Cat# SB 0155K-01 |

| ELISA HRP anti-human IgA | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 109-035-011 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Human stool in St. Louis: control, IBS-D, IBD, RA | Collected for this paper | https://research.wustl.edu/core-facilities/biobank-core-digestive-disease-research-core-center/ |

| Human stool in Baltimore, Celiac sprue | Collected by Alessio Fasano | N/A |

| Human stool in Rochester: control and IBS-D | Collected by Purna Kashyap | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Ovalbumin | Sigma | Cat# A5503 |

| N-acetyl-cysteine | Sigma | Cat# A7250 |

| DAPI | Sigma | Cat# D9542 |

| Cholera toxin | Sigma | Cat# C8052 |

| Lysine fixable tetramethylrhodamine labeled 10 kd dextran | Invitrogen | Cat# D1817 |

| Atropine chloride | Sigma | Cat# A0132 |

| Tropicamide | Sigma | Cat# T9778 |

| LPS | Sigma | Cat# L2630 |

| Murine EGF | Shenandoah | Cat# 200-53AF |

| Murine EGFRi (Tryphostin AG 1478) | Sigma | Cat# T4182 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| SMARTer Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit – Hi Mammalian | Takara | www.takara.com |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data (16s rRNA sequencing and RNA seq) | This paper | ENA Accession # PRJEB40130 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse; C56 BL/6J Foxp3IRES-GFP | Jackson | Cat# 6769 |

| Mouse; OTII | Jackson | Cat# 4149 |

| Mouse; Rag1–/– | Jackson | Cat# 2216 |

| Mouse; C57BL/6J gnotobiotic | Author’s facility | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 16s primer: F-5′-GGTGAATACGTTCCCGG-3′ and R-5′-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′ | Kostic et al.65 | IDT DNA |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| UPARSE | Edgar66 | https://www.drive5.com/usearch/manual/uparseotu_algo.html |

| Seqmatch RDP v2.6 | Wang et al.67 | https://rdp.cme.msu.edu/ |

| Phyloseq v1.19.1 | McMurdie and Holmes68 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gbm/gbm.pdf |

| Vegan | Oksanen et al.69 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html |

| DESeq2 v1.24 | Love et al.70 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| GBM v2.1.5 | Greenwell et al.71 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gbm/gbm.pdf |

| pROC v1.10.0 | Robin et al.72 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pROC/pROC.pdf |

| STAR v2.0.4b | Dobin et al.73 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| Sailfish v0.6.3 | Patro et al.74 | http://www.cs.cmu.edu/∼ckingsf/software/sailfish/ |

| RSeQC v2.3 | Wang et al.75 | http://rseqc.sourceforge.net/ |

| EdgeR | Robinson et al.,76 McCarthy et al.77 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html |

| GAGE | Luo et al.,91 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/gage.html |

| Pathview | Luo and Brouwer78 | https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/pathview/inst/doc/pathview.pdf |

| Prism v8 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| R v3.6 | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| QIIME v1.9.1 | Caporaso et al.79 | http://qiime.org |

| Limma | Ritchie et al.80 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Chyi-Song Hsieh (chsieh@wustl.edu).

Materials Availability

STL stool specimens used in this study, where available, can be obtained via requests to and approval from the Washington University DDRCC BioBank core: https://ddrcc.wustl.edu/scientific-cores/biobank-core/. Mayo stool samples in this study are not available due to IRB restrictions but all the data from these samples has been recently published44 and deposited in public databases.

Data and Code Availability

16S rRNA sequencing and RNaseq data is available at the European Nucleotide Archive (Accession # PRJEB40130). The programs supporting the current study are publicly available.

Experimental Model And Subject Details

Animals

Experiments were performed in an SPF or GF facility in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington University in St. Louis. Host mice were housed together and interbred to maintain microbial integrity. Male and female 6-10 week old C57 BL/6J Foxp3IRES-GFP (Jackson #006769) or wild-type littermate hosts were used for all SPF experiments unless specified otherwise. Foxp3IRES-GFP OTII Rag1–/– mice were bred from mice obtained from Jackson (#6769, #4194, #2216, respectively). C57BL/6J gnotobiotic mice were maintained in flexible plastic isolators on a strict 12h light cycle and mice were weaned onto autoclaved, standard mouse chow diet (Lab Diet 5053). Cages were changed every week by husbandry staff. All cages were randomly assigned into different treatment groups. Males and females were used equally in all experiments except for abdominal hypersensitivity due to availability at the contributing authors’ facility. No analysis on influence of sex was performed due to inadequate sample sizes. All experiments were performed independently at least two times unless otherwise stated.

Human subjects

All human stool specimen and medical data were collected with institutional review board compliance at Washington University in St. Louis, MO, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, and Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Inclusion criteria for Celiac Sprue, Rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients were physician’s diagnosis of disease supported by appropriate laboratory measures. Inclusion criteria for IBS-D subjects included patient symptoms of abdominal pain associated with diarrheal-predominant bowel pattern, consistent with Rome III diagnostic criteria.81 Exclusion criteria for all IBS and controls included antibiotic treatment in the last month and diagnosis of any other concurrent gastrointestinal disease, including intestinal resections. We attempted to obtain the PHQ15,82 IBS-symptom severity score (IBS-SSS)83 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)84 from all IBS patients; however, only a random subset returned these questionnaires. Cohort data are detailed in Tables S1 and S2 and Data S1.

Method Details

OTII expansion

FACS-purified 105 naive (CD4+Foxp3-CD25-CD62LhiCD44lo) Rag1–/– OTII from cdMLN cells were injected retro-orbitally, followed by 25 mg/mouse ovalbumin enema the following day, and analyzed 3 days later by flow cytometry. Cells from the cdMLN were stained with anti-CD4 BV700 (Biolegend), anti-CD45.1 A700 (Biolegend), anti-Va2 APC-Cy7 (Biolegend) and anti-CD45.2 PE (Biolegend), and analyzed on a FACSAria IIu.

CT2 transfers

FACS-purified 105 naive (CD4+Foxp3-CD25-CD62LhiCD44lo) from CD45.2 Foxp3Thy1.1Rag1−/− TCR Tg mice (CT2) were injected retro-orbital in stressed mice on d5 of stress into congenic CD45.1 Foxp3gfp mice, and analyzed 3 days later by flow cytometry. Cells from cdMLN were stained with anit-CD4 BV700 (Biolegend), anti-CD45.2 PE (Biolegend), anit-CD45.1 A700 (Biolegend), cell trace violet PB (Invitrogen), anti-Thy1.1 PECy7 (Biolegend), anti-CD25 PerCP-Cy5.5 (Biolegend), anti-CD44 AF430 (Biolegend), anti-CXCR3 (APC). Divided transferred cells were identified as CD4+CD45.2+CD45.1-Va2+PB+ . Treg of divided TCR+ cells identified as % of Thy1.1+ cells among transferred cells. Host T cells were identified as CD4+CD45.1+CD45.2- .

Bacterial FACS and sequencing

Mouse terminal fecal pellets were frozen at −80°C in screw-cap tubes until FACS-sorting. For human fecal specimens, a ~20mg chip of stool was obtained from a stool aliquot stored at −80°C. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry as described.35 Briefly, fecal samples dissolved in PBS by vortexing and sonication. After centrifugation, the supernatant was frozen for free fecal IgA measurements by IgA ELISA as described.35 The pellet was resuspended in 5 mM N-acetyl-cysteine to break disulfide bonds in mucus and release bacteria. After washing, the samples were blocked with 20% FBS, then stained with DAPI, IgG FITC isotype, anti-IgA(APC), and IgG(PE) antibodies (Abcam), filtered through a 35 μm filter and analyzed by flow cytometery (FACSAria IIu). 200,000 events in the input were used for OTU frequency analysis, and 30,000 Ig-bound and unbound fractions were FACS-sorted for each sample. Sort-purity for Ig-bound bacteria was generally between 65 - 75%. To decrease contamination, ethanol was run through the cytometer during fluidics shutdown and autoclaved PBS was used as sheath fluid. Sheath fluid was also sorted and sequenced separately to identify any contaminant OTUs which were removed during data processing. A Pseudomonas spp. S27630 was the predominant contaminant in sheath fluid and was removed from all analysis as it is not a common gut inhabitant.85 A PCR reaction was set up in triplicate using 2 μL of concentrated bacteria/tube to amplify bacterial V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA using barcoded primers described previously.43 Pooled PCR products were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 250-bp paired-end reads).

16S rRNA analysis

OTU picking was performed as before35 using UPARSE (usearch v9, radius = 3%)66 based on a calculated OTU frequency that combines the sequencing data with the proportions obtained by flow cytometry per specimen. Taxonomy was based on species designations with > 97% confidence using Seqmatch or from the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP v2.6)67 classifier using default settings. 16S microbial composition analysis was performed on input sorted fraction using the using phyloseq (v1.19.1)68 in R after rarefaction. Unifrac or Bray-Curtis distance matrixes were calculated in phyloseq. Significance was calculated using the adonis call in vegan (v2.4-4 in R).69 For a subset of analyses, dada2 ASVs (v.1.12)86 were used. Clustering of ASVs was performed by size using UPARSE.

Analysis of Ig-enriched taxa

IgA-enrichment of a particular taxa is calculated as: Log2(% OTU in IgA+ /% OTU in IgA–). IgA-enrichment indices were arbitrarily capped at 5.61 (log2(ratio of 49)) or −5.61 for taxa present only in IgA+ or IgA– fraction. For taxa that were entirely absent in a fecal specimen, an “NA” was assigned. To account for sequencing errors and imperfect bacterial sorting purity, only OTUs with frequency > = 1/5000 counts were analyzed. To study generally relevant bacteria, only taxa present in > 25% of individuals in the group were analyzed. DESeq2 (v1.24 in R; using sfType = ”poscounts”)70 and LEfSe87 were used to compare Ig+ and Ig– sequencing data within sample.

Gradient boosted machine

Random forest is a machine learning algorithm commonly used to look at differences in the microbiome between groups,88 but does not handle NAs (not available) in the data intrinsically. While this is not an issue with absent taxa in the analysis of OTU frequency as it would be 0, absent taxa in IgA enrichment data would be represented by an NA. We therefore used gradient boosted machine modeling (gbm R package v2.1.5)71 to evaluate the bernoulli distribution with 5 fold cross-validation for all 16S or Ig enrichment data between two disease groups. To ensure that the approach was applicable across all the data, multiple trials were performed in which each trial was trained with a random 75% of the fecal specimens without replacement and tested against the remaining 25%. Optimization of n.minobsinnode, bag.fraction, and interaction.depth for area under the curve (AUC, pROC v 1.10.0)72 was performed on 20-40 trials for each set of parameters. N.trees was set at 10000, which was typically > two-fold higher than the optimum number determined by gbm. The final analysis used 160 trials to generate average prediction values per sample from ~40 trials as each sample is only in 1/4 of the trials in the test fraction, whereas relative influence of OTUs are from 160 trials.

Abdominal Mechanical Sensitivity

Somatic hyperalgesia was assessed by von Frey filaments as described previously.65,89 Briefly, the abdomen was shaved prior to the start of restraint stress. One day after the last stress, animals were placed on a metal screen mesh in individual enclosures. After 1 hour of acclimation in the presence of white noise, mice received 5 separate stimulations with each von Frey filament (North Coast Medical Inc.; 0.02, 0.08, 0.32 and 1.28 g), with > 15 s pauses between stimulations and > 5 m when switching filament size. The assessor of response to stimulation was blinded to the experimental group.

Modulation of motility and stress

To induce diarrhea, mice were administered 10 μg cholera toxin (Sigma) in 100 μL of PBS or PBS alone on d1 and d4 per rectal enema using a flexible 1.5” IV catheter. Mice were subjected to experimental stress through physical restraint in 50ml conical tubes with adequate ventilation for 2 hours/day on 7 consecutive days.28 During those 2 hours, food and water were withheld from control mice.

FMT experiments

Cecal contents were pooled between 3-5 mice, resuspended in 2ml of sterile PBS, filtered with a 70 μM filter. Bacterial load was standardized between stressed and control contents by 16S real time PCR with F-5′-GGTGAATACGTTCCCGG-3′ and R-5′-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′ primers.65 FMTs in stressed SPF mice were performed per-rectum at the end of the 2 hour stress cycle for all 7 days. FMT in GF mice were performed by a single oral gavage of 100 μL of cecal contents.

Diarrhea signs

Fecal output was measured counting the number of pellets produced by individual mice after 2 hours in an empty ice-cream container covered with a cage top for adequate ventilation. To calculate fecal water weight, a terminal fecal pellet was immediately stored in a sealed screw-cap tube, weighed on aluminum foil soon after collection, and then re-measured after drying at 80°C degrees overnight. The percentage of water is obtained from the ratio of dry/pre-baked weights.

Colon histology

Mouse colons were harvested and luminal contents removed with PBS washing, fixed, and stained by H&E. Colons were assessed for histologic inflammation (ulceration, mononuclear cell infiltration and edema) in a blinded fashion by a gastroenterologist and digital photographs were taken.

Bacterial translocation

As previously described,90 lymph nodes were homogenized in a Bullet Blender (Next Advance) for 3 minutes. 100 μL of homogenate was plated onto aerobic Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates and incubated at 37°C overnight prior to colony counting.

GAP measurement

GAPs were measured as previously described.38 Briefly, colon tissue was incubated with 100 μg lysine fixable tetramethylrhodamine labeled 10 kd dextran (Invitrogen) prior to fixation, blocking, DAPI staining, and sectioning. GAPs were identified as dextran-filled columns traversing the epithelium and containing a nucleus. In some experiments atropine chloride (pan-mAChR antagonist 500 μg/ml Sigma-Aldrich), tropicamide (mAChR4 selective antagonist, 100 μg/ml Sigma-Aldrich), LPS (10 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), recombinant murine epidermal growth factor (10 μg/ml Shenandoah), or cecal contents was added to the colonic explant culture. For EGF treatments, mice were administered per-rectum with either 100ul volume of PBS or 1ug of EGF (Shenandoah Biotech) in 100ul PBS at the end of the 2 hour stress cycle for all 7 days. For EGFRi experiments, unstressed adult mice were given intraperitoneal EGFRi (500ug/kg tryphostin AG 1478) injections or PBS vehicle for 7 days and then fecal pellets collected on day 8 for bacterial FACS.

RNA seq

Whole colon and cecum were harvested from mice, luminal contents removed, and tissue washed thoroughly with PBS before snap freezing at 100 mg tissue/ml of TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA was prepared using the Takara SMARTer Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit – Hi Mammalian for sequencing on a HiSeq 3000 (50bp single end). RNA-seq reads were aligned to the Ensembl release 76 top-level assembly with STAR v2.0.4b.73 Gene counts were derived from the number of uniquely aligned unambiguous reads by Subread:featureCount version 1.4.5. Transcript counts were produced by Sailfish version 0.6.3.74 Sequencing performance was assessed for total number of aligned reads, total number of uniquely aligned reads, genes and transcripts detected, ribosomal fraction known junction saturation and read distribution over known gene models with RSeQC version 2.3.75 All gene-level and transcript counts were then imported into the R/Bioconductor package EdgeR76,77 and TMM normalization size factors were calculated to adjust samples for differences in library size. Genes or transcripts not expressed in any sample or less than one count-per-million in the minimum group size minus one were excluded from further analysis. The TMM size factors and the matrix of counts were then imported into R/Bioconductor package Limma80 and weighted likelihoods based on the observed mean-variance relationship of every gene/transcript and sample were then calculated for all samples with the voomWithQualityWeights function. Gene/transcript performance was assessed with plots of residual standard deviation of every gene to their average log-count with a robustly fitted trend line of the residuals. Generalized linear models were then created to test for gene/transcript level differential expression. To enhance the biological interpretation of the large set of transcripts, grouping of genes/transcripts based on functional similarity and generation of pathway maps on known signaling and metabolism pathways curated by GO, was achieved using the R/Bioconductor packages GAGE91 and Pathview.78

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism v8, R v3.6, QIIME v1.9.179 were used for statistical and graphical analysis. Student’s t test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal Wallis test, generalized linear model (GLM), Pearson’s correlations were used for between-subjects and continuous data analyses. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal Wallis tests were used only on 16S data where normal distribution cannot be assumed. Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction, as noted by padj, were performed using the base stats package in R. Each figure legend details the statistical test use, value of n and SD if applicable, how significance was defined (∗ for p < 0.05, ∗∗ for p < 0.005, ∗∗∗ for p < 0.0005, unless otherwise specified).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and relatives who contributed samples to this collection and the team of research staff including Kelly Monroe and Darren Nix (Digestive Diseases Research Cores Center, Washington University School of Medicine) who contributed to subject recruitment and specimen acquisition. We would also like to thank Jessica Hoisington-Lopez at the Center for Genome Sciences and Systems Biology at Washington University School of Medicine for Miseq sequencing expertise and Jingquin Luo (Division of Biostatistics, Washington University) for advice regarding the statistical analyses. We thank the Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine for help with the genomic analysis. We would like to thank Ryan McDonough and Natalia Jaeger for assistance and expertise with the GF experiments.

The Washington University Digestive Disease Research Cores Center is supported by NIH grant P30DK052574. C.-S.H. is supported by NIH grants 1R01AI140755 and 1R01AI136515, BWF, ICTS (Washington University), and the Wolff Professorship. M.A.C. is supported by DK109384, CA206039, and the Daniel H. Present Senior Research Award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. A.L.K. is supported by NIAID K08 AI113184 and the AAAAI Foundation. V.K.S. is supported by NIDDK R01DK116178 to R.W.G. IV, the Urology Care Foundation Research Scholars Program, the Kailash Kedia Research Scholar Award, and NIDDK Career Development Award K01 DK115634. P.C.K. is supported by NIH grant DK114007, P.C.K. and D.K. are supported by the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics. The Center for Genome Sciences and Systems Biology at Washington University in St. Louis is partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center and by ICTS/CTSA grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. S.R. and E.V.R.-G. are supported by NIH grant T32 GM007200-42.

Author Contributions

S.R., K.A.K., G.S.S., R.W.G. IV, A.L.K., M.A.C., R.D.N., and C.-S.H. conceived the project and/or designed the experiments. A.F. provided the celiac sprue fecal specimens. D.K. and P.C.K. provided ROC IBS fecal specimens. A.R., P.R., G.S.S., M.A.C., and R.D.N. designed and assisted in patient recruitment and specimen collection in STL. A.L.K. also assisted with GF expertise. S.R., K.A.K., A.R., J.N.C., J.G.G., V.K.S., and E.V.R.-G. performed experiments and S.R., K.A.K., A.R., J.N.C., J.G.G., and V.K.S. analyzed the data. S.R. and C.-S.H. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests. D.K. serves as Senior Scientific Advisor to Diversigen, a company involved in the commercialization of microbiome analysis. Diversigen is now a wholly owned subsidiary of OraSure. P.C.K. is on the advisory board of Novome Biotechnologies and is an ad hoc consultant for Pendulum Therapeutics, IP Group, and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. These interests have been reviewed and managed by the respective institutions in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies.

Published: October 20, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100124.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Imam T., Park S., Kaplan M.H., Olson M.R. Effector T Helper Cell Subsets in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1212. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shale M., Schiering C., Powrie F. CD4(+) T-cell subsets in intestinal inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2013;252:164–182. doi: 10.1111/imr.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blander J.M., Longman R.S., Iliev I.D., Sonnenberg G.F., Artis D. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:851–860. doi: 10.1038/ni.3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Shima T., Imaoka A., Kuwahara T., Momose Y., Cheng G., Yamasaki S., Saito T., Ohba Y. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lathrop S.K., Bloom S.M., Rao S.M., Nutsch K., Lio C.W., Santacruz N., Peterson D.A., Stappenbeck T.S., Hsieh C.S. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 2011;478:250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu M., Pokrovskii M., Ding Y., Yi R., Au C., Harrison O.J., Galan C., Belkaid Y., Bonneau R., Littman D.R. c-MAF-dependent regulatory T cells mediate immunological tolerance to a gut pathobiont. Nature. 2018;554:373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature25500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch M.A., Reiner G.L., Lugo K.A., Kreuk L.S., Stanbery A.G., Ansaldo E., Seher T.D., Ludington W.B., Barton G.M. Maternal IgG and IgA Antibodies Dampen Mucosal T Helper Cell Responses in Early Life. Cell. 2016;165:827–841. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macpherson A.J., McCoy K.D., Johansen F.E., Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:11–22. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pabst O. New concepts in the generation and functions of IgA. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:821–832. doi: 10.1038/nri3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagarasan S., Honjo T. Intestinal IgA synthesis: regulation of front-line body defences. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:63–72. doi: 10.1038/nri982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews J.M., Holtmann G. IBD: stress causes flares of IBD--how much evidence is enough? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;8:13–14. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sgambato D., Miranda A., Ranaldo R., Federico A., Romano M. The Role of Stress in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017;23:3997–4002. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170228123357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey M.T., Dowd S.E., Parry N.M., Galley J.D., Schauer D.B., Lyte M. Stressor exposure disrupts commensal microbial populations in the intestines and leads to increased colonization by Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:1509–1519. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00862-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karl J.P., Hatch A.M., Arcidiacono S.M., Pearce S.C., Pantoja-Feliciano I.G., Doherty L.A., Soares J.W. Effects of Psychological, Environmental and Physical Stressors on the Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2013. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao X., Cao Q., Cheng Y., Zhao D., Wang Z., Yang H., Wu Q., You L., Wang Y., Lin Y. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E2960–E2969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720696115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtmann G.J., Ford A.C., Talley N.J. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;1:133–146. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett E.J., Tennant C.C., Piesse C., Badcock C.A., Kellow J.E. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1998;43:256–261. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]