Abstract

Aims

Bone demonstrates good healing capacity, with a variety of strategies being utilized to enhance this healing. One potential strategy that has been suggested is the use of stem cells to accelerate healing.

Methods

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, CENTRAL, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, WHO-ICTRP, ClinicalTrials.gov, as well as reference checking of included studies. The inclusion criteria for the study were: population (any adults who have sustained a fracture, not including those with pre-existing bone defects); intervention (use of stem cells from any source in the fracture site by any mechanism); and control (fracture healing without the use of stem cells). Studies without a comparator were also included. The outcome was any reported outcomes. The study design was randomized controlled trials, non-randomized or observational studies, and case series.

Results

In all, 94 eligible studies were identified. The clinical and methodological aspects of the studies were too heterogeneous for a meta-analysis to be undertaken. A narrative synthesis examined study characteristics, stem cell methods (source, aspiration, concentration, and application) and outcomes.

Conclusion

Insufficient high-quality evidence is available to determine the efficacy of stem cells for fracture healing. The studies were heterogeneous in population, methods, and outcomes. Work to address these issues and establish standards for future research should be undertaken.

Cite this article: Bone Joint Open 2020;1-10:628–638.

Keywords: systematic review, stem cells, Fracture

Introduction

Bone demonstrates excellent healing capacity, although the process by which this occurs is not well understood. The healing process is broadly split into three overlapping phases, inflammation, bone production and bone remodelling. A number of growth factors and various signalling molecules are responsible for bone healing. In all, 20 million people worldwide suffer from bone loss either from trauma or disease, leading to five million interventions.1

Overall, 10%of fractures may not heal and require further intervention.2 Delayed union and nonunion are expensive and burdensome to both patients and the healthcare system, with patients experiencing psychological distress and physical dysfunction, leading to a loss of working days. The estimated cost of treating nonunion is substantial across many healthcare settings.3-5

Multiple strategies can be employed to enhance bone healing; stability of bony construct, good bony contact and adequate vascularity to deliver cells, and growth factors. Alternate systemic and local therapies are developed to further augment the bone healing.6

The option of stem cells to enhance the rate of bone healing in acute fractures and improve bone healing in delayed/nonunion or in bone defects is of great interest to clinicians but not well understood. The osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells has been proven repeatedly in a number of human and animal studies,7 it has been shown that these cells are found in not only bone marrow but also adipose, periosteum, synovium and muscle tissue. One strategy that has been developed is the diamond concept which couples the current strategies of bone healing with the use stem cells in to a four part method.6

We undertook this systematic review with the aim of assessing the evidence regarding the use of stem cells in fracture healing and to establish what measures are being used to assess patient outcomes, in order to inform future research.

This review addressed four main questions:

What evidence is currently available assessing the effect of injection/implantation of stem cells on bone healing in fractures?

What interventions are being evaluated in terms of cell source, preparation and method of administration?

What methods do studies use to assess qualitative/quantitative bone healing/callus formation?

What other outcome measures do studies use?

Methods

Prior to finalizing search criteria a protocol was written and prospectively registered on PROSPERO, with the registration ID CRD42019142041.

Study selection

Studies that matched the following criteria were eligible for inclusion:

Adults with any form of fracture, who did not have pre-existing bone defects.

Utilization of stem cells to aid fracture healing, where stem cells could be from any source and provided by any mechanism. Fracture healing without the use of stem cells. Studies with no control group were also included.

Studies where any other interventions were provided to both control and intervention arms were eligible.

Outcomes

Any outcomes were acceptable as an objective of this review was to map the outcomes used in studies. Key outcomes of interest were fracture healing, time to fracture healing, delayed or nonunion, the strength of bone post resolution, stem cell regeneration at the fracture site, functional outcome (e.g. range of movement or patient-reported outcomes), quality of life, complications, and adverse events.

Study design

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized or observational studies, and case series in any publication format were included in the study. We also included research registrations and protocols for these designs to identify ongoing research.

Searches were developed and performed by an information specialist (MH). A search strategy was developed in Ovid MEDLINE consisting of a set of terms for bone fractures combined with a set of terms for stem cells. Both text word searches in the title and abstracts of records and subject headings were included in the strategy. The wider review team were consulted during the drafting of the search strategy to ensure all relevant terms were included. No date or language limits were applied and the searches were designed to retrieve all study types. The strategy was tested in MEDLINE to ensure retrieval of key known studies and then adapted for use in all other resources searched. The following databases were searched from inception to 9 July 2019: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Wiley), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Wiley), clinicaltrials.gov, and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO-ICTRP) to identify published, unpublished, and ongoing studies. The full search strategy for all sources is provided in the supplementary material.

The results of the searches were de-duplicated using EndNote X8 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) and uploaded to Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for the screening process. Titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria by two independent researchers, with any discrepancies between the decisions being resolved through discussion. Full-texts were obtained for those that were potentially eligible and these were screened against the eligibility by two independent researchers, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion. Any additional references identified in reviews or included papers that had not been previously identified were also screened.

Two members of the team (AMo, AMi) developed and pilot tested a data extraction form using Google Forms (Mountain View, California, USA), designed around the study objectives. Once finalized, each eligible study was extracted by two independent researchers, with a third resolving any discrepancies.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessments were completed based on study design, with case series being assessed against the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for case series,8 observational and non-randomised studies were assessed against the ROBINS-I assessment tool,9 and RCTs were assessed against the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool.10 Each study was assessed by one researcher, with another researcher checking the first assessment. Where only a protocol or registration was available an assessment was not completed.

Synthesis of results

A narrative synthesis of studies together with tabulation of study characteristics and results was undertaken. Full details of the intervention characteristics were described including stem cell type, preparation and mode of administration as well as outcomes assessed and follow-up duration.

The key subgroups of interest were the source of stem cells, timing ,and method of administration.

Results

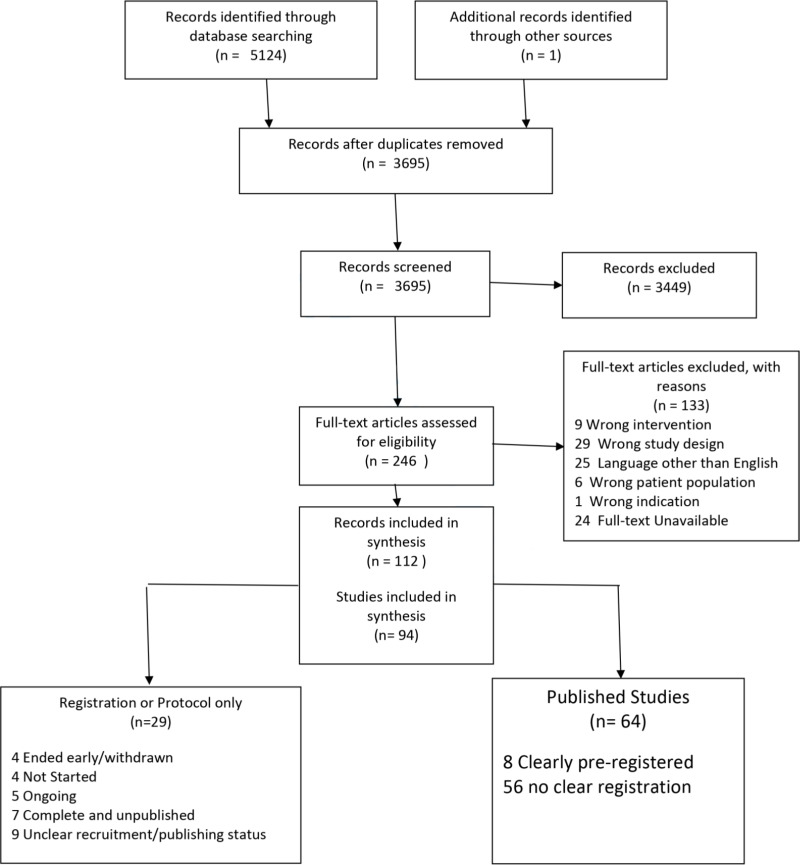

A total of 5,125 records were identified, and following de-duplication 3,695 records were identified for screening. A summary of the number of records at each stage of the review can be found in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study records.

There were 94 eligible studies,11-104 of these 26 were RCTs, 26 were observational/non-randomised studies, and 42 were case-series (19 prospective, 23 retrospective). A summary of study characteristics is provided in the supplementary material. The studies included acute fractures (23 studies), nonunion or pseudoarthrosis (66 studies), with five studies having a combination of these (Table I). The earliest study was published in 2005. Of the eligible studies, 29 (18 RCTs, nine observational/non-randomized, two case series) were identified as protocols or registrations and thus no results were available.

Table I.

Site and type of fracture in included studies (n = 94).

| Bone | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Any bone | |

| Acute | 1 (1.1) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 1 (1.1) |

| Combination | 2 (2.1) |

| Any long bone | |

| Acute | 1 (1.1) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 10 (10.6) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Tibia | |

| Acute | 8 (8.5) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 40 (42.5) |

| Combination | 1 (1.1) |

| Fibula | |

| Acute | 2 (2.1) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 8 (8.5) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Humerus | |

| Acute | 3 (3.2) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 19 (20.2) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Mandible | |

| Acute | 3 (3.2) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 0 (0) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Ulna | |

| Acute | 1 (1.1) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 14 (14.9) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Radius | |

| Acute | 1 (1.1) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 10 (10.6) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Metatarsal | |

| Acute | 5 (5.3) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 1 (1.1) |

| Combination | 0 (0) |

| Any ankle bone | |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 2 (2.1) |

| Other (clavicle, scaphoid, pelvis) | |

| Acute | 1 (1.1) |

| Nonunion/pseudoarthrosis | 2 (2.1) |

The quality assessment of the case series (online supplementary material) indicated that 66.7% (28/42) provided clear eligibility criteria, 54.7% (23/42) reliably applied the eligibility criteria, and 88.1% (37/42) clearly reported outcomes.

The quality assessments of the observational studies indicated all those with published data were at either moderate or serious risk of bias.

The quality assessments of the RCTs indicated that for all available trials there were either some concerns regarding potential bias or a high risk of bias. All quality assessment results are available in the supplementary material.

We also assessed the funding or support received for conduct of these studies, 65 studies did not report any details regarding support or funding, 23 reported funding for the study, and six reported partial support (provision of equipment, writing support, or other).

Eight of the 26 RCTs for which we identified published results; these eight had populations, methods, and outcomes that were too heterogeneous for meta-analyses to be appropriate (Table II). We therefore completed a narrative synthesis.

Table II.

Included trials with published results.

| Author (year) | Source of cells | Age for inclusion (years) | Type of fracture | Site of fracture | Number of participants | Healing definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang (2018)14 | Bone | 18 to 50 | Nonunion | Tibia | 25 | Specified only union |

| Zhai (2016)15 | Bone | > 18 | Nonunion | Humerus, ulna, femur, tibia, radius | 63 | Blurred fracture line, no pain on percussion, and functionality is suitable after removal of external fixation |

| Yuan (2010)16 | Bone | Not reported | Nonunion | Tibia/humerus | 140 | Callus Formation |

| Liebergall (2013)35 | Bone | 18 to 65 | Acute | Tibia | 24 | lack of pain during weight-bearing and bridging of three out of four cortices |

| Muthian (2018)38 | Bone | Not reported | Combination | Tibia | 55 | Specified only union |

| Mannelli(2017)42 | Bone | > 65 | Acute | Mandible | 36 | No healing outcome |

| Kim (2009)43 | Bone | Not reported | Acute | Any long bone | 64 | Study Specific Score base on callus formation |

| Castillo-Cardiel (2017)59 | Adipose | 17 to 59 | Acute | Mandible | 20 | Voxel counting of CT image |

Stem cell specific technique

The techniques related to the stem cells that are employed in the included studies varied in a number of aspects.

Bone marrow derived stem cells were used in 84 studies (89.4%), seven used adipose derived cells (7.4%), and three used umbilical cord derived cells (3.2%). Two studies reported using more than one source of cells. Three studies (3.2%) did not report the source of the cells.

For those that used bone or adipose the majority used autologous cells with a small number using allografts. Details of donors of allografts was not specified in five studies, in one study donor eligibility was provided for all three types of tissue (bone, adipose, and umbilical) and one study used cadaveric donor tissue. Table III summarises the sources of the cells used in the included studies.

Table III.

Cell Sources reported in included studies (n = 94).

| Source | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Bone | |

| Autograft | 74 (78.7) |

| Allograft | 3 (3.2) |

| Unreported/unclear | 5 (5.3) |

| Both | 2 (2.1) |

| Adipose | |

| Autograft | 4 (4.2) |

| Allograft | 3 (3.2) |

| Unreported/unclear | 0 (0) |

| Umbilical | 3 (3.2) |

| Unreported | 3 (3.2) |

Of the included studies that used bone marrow as a source of stem cells there were 64 (76.2%) that used the ilium, one (1.2%) used the tibia, one (1.2%) used a combination of these, and 18 (21.4%) did not report the source of the bone marrow used.

The methods used to aspirate cells were Reamer-irrigator-Aspirator (three, 3.2%), Jamshidi (seven; 7.4%), trocar (three; 3.2%), needle (24; 25.5%), other (two; 2.1%), and was unreported in 55 (58.5%) studies. The method of aspiration was reported only in studies using bone as the source of cells.

Table IV summarizes the methods of aspiration, concentration, and application of the cells used from the different sources.

Table IV.

Aspiration, concentration, and application of the stem cells based on the source of the cells.

| Variable | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone (n = 83) |

Adipose (n = 7) |

Umbilical (n = 3) |

Overall (n = 94) |

|

| Volume of aspirate, ml * | ||||

| Number of studies | 50 | 3 | 2 | 52 |

| Mean (SD) | 103.3 (119.6) | 91.7 (72.2) | 45.0 (7.1) | 103.6 (117.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 60 (35.0 to 105.0) | 50 (50.0 to 175.0) | 45 (40 to 50) | 60 (37.5 to 115.0) |

| Min to max | 4 to 500 | 50 to 175 | 40 to 50 | 4 to 500 |

| Method of concentration, n | ||||

| Centrifuge | 46 | 2 | 1 | 48 |

| Culture | 17 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| SECCS | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Not reported | 20 | 3 | 1 | 25 |

| Volume of concentrated cells, ml * | ||||

| Number of studies | 36 | 0 | 1 | 36 |

| Mean (SD) | 15.1 (13.5) | NA | 4.0 (N/A) | 15.1 (13.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (6.75 to 20.0) | NA | 4.0 (4.0 to 4.0) | 10 (6.75 to 20.0) |

| Min to max | 1.5 to 50 | N/A | 4.0 to 4.0 | 1.5 to 50 |

| Method of application, n | ||||

| Injection | 34 | 1 | 2 | 37 |

| Implant | 27 | 2 | 1 | 30 |

| On scaffold | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Unreported | 9 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

Some studies reported more than one method and some studies did not report the method so the sum of the figures in the three method columns do not necessarily equal the overall.

For each study a range or point estimate was taken, the mean of the ranges was taken to give a point estimate for each study, these were then used to calculate the mean, median, and standard deviation.

IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation; SECCS, screen-enrich-combine circulating system.

Where reported, the type of centrifuge based system varied between the studies: Harvest System (eight; 16.7%), Cobe (five; 10.4%), Magellan (three; 6.3%), Sepax (three; 6.3%), Aastrom (two; 4.2%), Sorvall (two; 4.2%), Lymphodex (two; 4.2%), Angel (one; 2.1%), Regen (one; 2.1%), Cellution (one; 2.1%), Kubota (one; 2.1%), and Percoll (one; 2.1%). Four studies noted the use of the Ficoll-Paque standard.

Concurrent interventions

Surgical fixation was the most common concurrent intervention provided with the stem cell intervention. Internal fixation was used in 28 studies, external fixation in 25 studies, 33 studies specified only the use of nailing, nine studies specified only screws, and one used a Kirschner wire.

Six studies reported using the diamond concept (this includes stem cells (osteogenic cells), osteoconductive scaffold, growth factors, and the mechanical environment), other studies did not use the diamond concept but did apply individual aspects of it alongside the stem cells.

Other interventions included: Mattie-Russe method, collagen scaffold, Hydroxyapatite scaffold, segmental excision, intermedullary rod, platelet lysate product, platelet rich fibrin, demineralized bone marrow, lypholised bone chips, osteotomy, beta-TCP, osseous matrix implantation, low-intensity pulsed ultrasound, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy.

In all, 26 studies provided details of further treatment required or the guidelines that were used to guide further treatment.

Outcomes used

Overall, 89 of the included studies reported use of a healing outcome. Time-to-healing was reported in 28 of these, proportion healed at a given time point was reported in 40, 14 reported both of these, four provided an average measured healing score for at least one time point, and three did not make clear the how the measure was defined despite specifying the outcome.

Healing outcomes fell into three broad categorisations: only radiological outcomes (51 studies), only clinical outcomes (two studies), and combined radiological and clinical outcomes (31 studies); five studies did not provide a clear enough healing definition to be categorized. Table V summarises the frequency of the components used to assess healing.

Table V.

Summary of the frequency of healing outcome components (n = 89).

| Measure | Number of studies (% of studies reporting healing) |

|---|---|

| No specific radiological measure or definition given* | 27 (30.3) |

| Qualitative radiological evaluation without scoring | |

| Blurred fracture or no fracture line | 9 (10.1) |

| Callus formation | 28 (31.5) |

| Cortices bridging (75%) | 22 (24.7) |

| Qualitative radiological evaluation with scoring | |

| Radiological Union Scale in Tibial fractures (RUST)105 | 2 (2.2) |

| Lane and Sandhu criteria106 | 2 (2.2) |

| Tiedemann criteria107 | 1 (1.1) |

| Study specific criteria | 2 (2.2) |

| Assessment of callus blood supply with contrast enhanced ultrasound | 1 (1.1) |

| Quantitative radiological evaluation | |

| Voxel or pixel counting | 1 (1.1) |

| Callus volume measure | 2 (2.2) |

| Hounsfield units | 4 (4.5) |

| New bone ratio | 1 (1.1) |

| Bone mineral content | 2 (2.2) |

| Qualitative clinical evaluation | |

| No pain on compression, palpatation, or percussion | 3 (3.4) |

| Weightbearing/partial weightbearing | 13 (14.6) |

| Removal of external fixation | 4 (4.5) |

| Qualitative clinical evaluation with scoring | |

| Specific threshold on pain scale | 3 (3.3) |

Includes studies that defined healing as “bony fusion”, “union”, “consolidation”, or “bone formation” as these are all non-specific.

Outcomes other than healing were grouped into seven categories: quality of life, pain, injury/population specific, range of movement, adverse events, and cellular categorization. Table VI records the number of studies using patient reported outcomes and range of movement measures.

Table VI.

Patient-reported outcomes and range of movement.

| Outcome | Number of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Quality of life | |

| EQ-5D | 6 (6.4) |

| SF-36 or SF-12 or SF-HLQ | 8 (8.5) |

| Satisfaction (any rating scale) | 2 (2.1) |

| Visual analogue scale | 1 (1.1) |

| No specified measure | 1 (1.1) |

| Pain | |

| Visual analogue scale | 15 (16.0) |

| PROMIS (interference) | 1 (1.1) |

| Numeric rating scale | 1 (1.1) |

| Other | 2 (2.1) |

| Injury or population-specific measures * | n = 14 |

| DASH | 5 (5.3) |

| OSS | 1 (1.1) |

| LEFS | 3 (3.2) |

| FAOS | 2 (2.1) |

| FAAM | 2 (2.1) |

| SMFA | 1 (2.1) |

| KOOS | 1 (1.1) |

| Time to return to sport | 2 (2.1) |

| Time to return to daily activities | 1 (1.1) |

| Range of movement* | 6 (6.4) |

These outcomes would not be an appropriate measure for all studies.

DASH, Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand; EQ-5D, EuroQol- 5 Dimension; FAAM, Foot and Ankle Ability Measure; FAOS, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome; LEFS, Lower Extremity Function Score; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SF-12, 12-item Short Form Survey; SF-36, 36-item Short Form Survey; SF-HLQ, Short Form-Health and Labour Questionnaire; SMFA, Short Musculoskeletal Functional Assessment.

Adverse events

The method used for adverse event reporting was reported in 46 (48.9%) studies. However, only 7 (7.4%) studies provided clear definitions for how events would be classified.

Reactions to stem cells were assessed in five studies, complications at the harvest site were assessed in 24 studies, infection at the administration site was assessed in 35 studies and complications with metalwork were assessed in 12 studies. Of the five studies assessing reaction to stem cells one study reported any immediate reaction, with one study reporting an allergic skin reaction in one patient.14 This occurred after the participant received an injection of 20 ml of autologous bone marrow concentrated by centrifuge for their tibial nonunion, no details are provided regarding the timing of this event. It is noted that it was managed with oral antihistamine.

Other adverse events that were reported to be assessed by other studies, although did not necessarily occur, were: refracture (one study), haematoma (four studies), oedema (two), fistula development (one), pulmonary embolism (two), anaphylaxis (one), neoplasm/malignancy (four), wound dehiscence (two), nerve injury (two), nerve palsy (one), malunion (two), chronic pain at administration site (one), amputation (one), charcot arthropathy (one), skin necrosis (one), compartment syndrome (one), deep vein thrombosis (one), avascular necrosis (one), arthrofibrosis (one), heart failure (one), and excessive bone formation (one).

Cellular categorization

Attempts to categorize or identify the cells that were isolated and used was made in 33 (35.1%) of the included studies.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

We identified 94 studies that reported the use of stem cells for fracture healing in adults by searching literature databases and research registries; of these, 29 had yet to publish any results. Only eight RCTs were available with results. For the randomized evaluations that had available results, the eligibility criteria, methods relating to the intervention, and outcomes were too heterogeneous to enable meta-analyses.

Of the studies with reported results the quality assessment suggested that all RCTs and observational studies had some concerns regarding bias or were at high risk of bias. Therefore, there is not yet sufficient high-quality evidence for us to draw any conclusions regarding the efficacy of stem cells for fracture healing. The studies that were included were able to provide details regarding the study populations, methods, and outcomes that will be valuable in the design of future studies that can be used to assess efficacy.

Many of the issues identified here correspond with those raised by the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) regarding the use of stem cell therapies and other systematic reviews on the topic.108-110 The ISCT identified that many cellular therapies do not have sufficient evidence from basic lab work to clinical evaluation and often they lack a standardized approach to confirm the quality and consistency of the cells used. Our review both confirms these issues and adds to this evidence that for studies assessing stem cells in fracture healing there is also a lack of comparable outcomes for assessment of fracture healing.

Stem cell technique

The majority of studies utilized autologous bone marrow sourced from the ilium, centrifugation of the aspirated marrow for concentration of cells, and injected or implanted the concentrated cells with no scaffold. However, even among these studies there was heterogeneity in the methods of cellular aspiration, concentration methodology (varying centrifuge technology), and concurrent interventions.

The heterogeneity of these methods is unlikely to change in future research, as the availability of different commercial kits will only increase. Therefore, in order to provide a more standardized and comparable intervention there is a need for better and more consistent categorization of the type and amount of concentrated cells used in any study and for this to be reported.

Some studies have also suggested that the availability and the regenerative potential of cells change with age and that this may differ with the source of the cells.111,112 Future studies should consider the age, source, and the available quantity and quality of the cells, this would allow clinicians to make decisions on the appropriate approach for patients of different ages.

Reporting of key aspects of the intervention in the included studies was poor. Given that the source, preparation, and application of these cells are likely to impact upon the efficacy of the intervention this information should be a minimum reporting requirement for any future studies. As well as this a larger focus should be given to the type, quantity and quality of the cells used in these studies. One way this could be done is to use the guidelines produced by the ISCT, these outline the criteria for defining a mesenchymal stem cell and the appropriate classification and reporting of these interventions.113,114

Healing outcomes

Increased rates of healing are beneficial as it reduces the need for further intervention, complications, and nonunions. One of the purported benefits of using stem cells is that it will accelerate the healing process. Therefore, time-to-healing may be an important measure of healing. Time-to-healing data is presented in 28 of the included studies however few reported follow-up schedules that would allow reasonable analyses to be undertaken to assess differences between groups. While it is possible to use an appropriate analysis for interval-censored data, such as this, there are issues that arise when the outcome has both radiological and clinical aspects and as the length of time between follow-ups increases.115 Any future studies considering a time-to-healing outcome should carefully consider the study follow-up schedule required to assess any differences in time-to-healing between groups in the relevant bone.

Nearly one-third (n = 27; 30.3%) of the included studies did not provide a specific definition of healing and the healing definitions that were most utilized were subjective. The use of quantitative assessment was low. Healing outcomes should be more well defined and further research is required to define and validate these outcomes.

The most appropriate methods for assessing fracture healing may differ with the site and type of fracture. However, even bone specific reviews and fracture healing reviews have found that there is heterogeneity of outcomes with similar characteristics to those included in our review.116,117 A well developed core outcome set (COS) that covers the appropriate outcomes, in terms of assessment and measure that can be used across fractures or for specific populations would reduce this heterogeneity for future research.118 One previous attempt at developing a COS for fracture healing in osteoporosis notes the need for measuring time to union but recognizes identical issues that are raised in this review regarding the heterogeneity of potential outcomes.119 The need for identifying the appropriate outcomes was the top research requirement in a recent James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership project regarding fractures in older people.120 The development of a COS must be done in alignment with pre-existing international standards and taking into consideration patient and public opinion.121

Other outcomes

The other measures used in the included studies covered the main domains that might be expected in fracture trials (pain, quality of life, outcomes specific to the injury, and range of movement). However, the vast majority of studies did not report these outcomes, especially when compared to the large number that reported a healing outcome. Had more included studies provided a measure of pain or quality of life these could have provided an indication of effectiveness of stem cells on these outcomes.122 The development and uptake of a COS with the involvement of patients and the public would resolve this.

Strengths and limitations

Our review provides a comprehensive overview of the methods being used to evaluate the use of stem cells for fracture healing. We included studies that are yet to be published or that were never completed. While these studies could not provide data on the efficacy of the intervention this allowed us to assess the full range of methods that are being utilized in these studies.

It should be noted that a large number of studies were identified (but excluded) that utilized a bone graft or bone marrow aspiration and injection without concentration. These grafts may have contained stem cells but the authors made no reference to the preparation, isolation, or inclusion of stem cells. This intervention was used as a control intervention to compare to concentrated stem cells in some studies, therefore studies using this intervention alone were not included as they cannot provide details related to the specific intervention objectives of this review. These studies may have been able to provide some information about the extraction of bone marrow and the outcomes used for fracture healing.

A large number of studies were also excluded for not being available in English. This may limit the comprehensiveness of this review. This may be especially important as international regulatory requirements for stem cell research differ quite widely, especially with regards to the sourcing and preparation of such cells.123,124

There is a clear need for standardization across studies and work is required to enable this before future research is conducted. Such work may include the development of a COS, minimum reporting standards, and co-ordination of research into different populations. This should be done in alignment with international standards and patient and public opinion.

Take home message

- There are few high-quality published studies assessing the use of stem cells for fractures.

- Future studies need to ensure that there is appropriate standardisation of procedures and categorisation of cells, as well as meeting international standards for the conduct and reporting of these studies.

Supplementary material

Tables showing search strategies, study characteristics, Joanna Briggs Institute case series assessments, ROBIS assessments of non-randomized and observational studies, and ROB2 assessments of randomized controlled trials.

Footnotes

Author contributions: A. Mott: Undertook design, screening, extraction, quality assessment, synthesis, and interpretation, Drafted the manuscript.

A. Mitchell: Undertook design, screening, extraction, synthesis, and interpretation, Drafted the manuscript.

C. McDaid: Undertook design and interpretation.

M Harden: Undertook searching.

R. Grupping: Undertook design and screening, Interpreted the results, Reviewed the manuscript.

A. Dean: Undertook screening, extraction, and quality assessment.

A. Byrne: Undertook screening, extraction, and quality assessment.

L. Doherty: Undertook extraction and quality assessment.

H. Sharma: Undertook design, literature search, and interpretation.

Funding statement: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical review statement: Registration ID: CRD42019142041

References

- 1. Habibovic P. Strategic Directions in Osteoinduction and Biomimetics. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23(23-24):1295–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Fracture healing: mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(1):45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giorgio Calori M, Capanna R, Colombo M, et al. Cost effectiveness of tibial nonunion treatment: a comparison between rhBMP-7 and autologous bone graft in two Italian centres. Injury. 2013;44(12):1871–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. The health economics of the treatment of long-bone non-unions. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl 2):S77–S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antonova E, Le TK, Burge R, Mershon J. Tibia shaft fractures: costly burden of nonunions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giannoudis PV, Einhorn TA, Marsh D. Fracture healing: the diamond concept. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl 4):S3–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liao Y, Zhang X-L, Li L, Shen F-M, Zhong M-K. Stem cell therapy for bone repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies with large animal models. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(4):718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. JBI Reviewer’s Manual. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Toro G, Lepore F, Calabrò G, et al. Humeral shaft non-union in the elderly: results with cortical graft plus stem cells. Injury. 2019;50 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S75–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thua THL, Pham DN, Le QNB, et al. Mini-invasive treatment for delayed or nonunion: the use of percutaneous autologous bone marrow injection. Biomed Res Ther. 2015;2(11). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhuang Y, Gan Y, Shi D, Zhao J, Tang T, Dai K. A novel cytotherapy device for rapid screening, enriching and combining mesenchymal stem cells into a biomaterial for promoting bone regeneration. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang H, Xue F, Jun Xiao H. Ilizarov method in combination with autologous mesenchymal stem cells from iliac crest shows improved outcome in tibial non-union. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2018;25(4):819–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhai L, Ma X-L JC, Zhang B, Liu S-T, Xing G-Y. Human autologous mesenchymal stem cells with extracorporeal shock wave therapy for nonunion of long bones. Indian J Orthop. 2016;50(5):543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yuan J-G, Zhou Z-L, Liu Y-F, Zhu Z-A. Autologous bone marrow stem cell transplant versus autologous iliac bone graft for bone nonunion treatment. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Research. 2010;14(1):183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wittig O, Romano E, González C, et al. A method of treatment for nonunion after fractures using mesenchymal stromal cells loaded on collagen microspheres and incorporated into platelet-rich plasma clots. Int Orthop. 2016;40(5):1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weel H, Mallee WH, van Dijk CN, et al. The effect of concentrated bone marrow aspirate in operative treatment of fifth metatarsal stress fractures; a double-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang X, Chu W, Zhuang Y, et al. Bone mesenchymal stem cell-enriched β-Tricalcium phosphate scaffold processed by the Screen-Enrich-Combine circulating system promotes regeneration of diaphyseal bone non-union. Cell Transplant. 2019;28(2):212–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seebach C, Henrich D, Meier S, Nau C, Bonig H, Marzi I. Safety and feasibility of cell-based therapy of autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells in plate-stabilized proximal humeral fractures in humans. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gasbarra E, Rao C, Feola M, Tempesta V, Tarantino U. Bone marrow concentrate as an osteogenic support in the treatment of forearm nonunions. In-Depth Oral Presentations and Oral Communications. 2013:S67. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sugaya H, Mishima H, Aoto K, et al. Percutaneous autologous concentrated bone marrow grafting in the treatment for nonunion. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(5):671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pozza S, De Marchi A, Albertin C, et al. Technical and clinical feasibility of contrast-enhanced ultrasound evaluation of long bone non-infected nonunion healing. Radiol Med. 2018;123(9):703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Malley M, DeSandis B, Allen A, Levitsky M, O'Malley Q, Williams R. Operative treatment of fifth metatarsal Jones fractures (zones II and III) in the NBA. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(5):488–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scaglione M, Fabbri L, Dell’Omo D, Gambini F, Guido G. Long bone nonunions treated with autologous concentrated bone marrow-derived cells combined with dried bone allograft. Musculoskelet Surg. 2014;98(2):101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rush SM, Hamilton GA, Ackerson LM. Mesenchymal stem cell allograft in revision foot and ankle surgery: a clinical and radiographic analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48(2):163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodriguez-Collazo ER, Urso ML. Combined use of the Ilizarov method, concentrated bone marrow aspirate (cBMA), and platelet-rich plasma (PrP) to expedite healing of bimalleolar fractures. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2015;10(3):161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giannoudis PV. Tibial Fracture - Platelet-rich Plasma and Bone Marrow Concentrate (T-PAC). ClinicialTrials.gov. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT03100695 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 29. Granell Álex. Mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of non-union fractures of long bones. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02230514 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 30. Saxer & Jakob Effectiveness of adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells as osteogenic component in composite grafts (robust). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01532076 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 31. Hauzeur M. Treatment of atrophic nonunion by Preosteoblast cells. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2012. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT00916981 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 32. Rosset Percutaneous autologous bone-marrow grafting for open tibial shaft fracture (IMOCA). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT00512434 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 33. Machi E, Pamelin E, Bertolotti M. Scaphoid non-union treatment with corticocancellous bone graft and stem cells from bone marrow. Chir Main. 2011;30(6):453. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lovy AJ, Kim JS, Di Capua J, et al. Intramedullary nail fixation of atypical femur fractures with bone marrow aspirate concentrate leads to faster Union: a case-control study. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(7):358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liebergall M, Schroeder J, Mosheiff R, et al. Stem cell-based therapy for prevention of delayed fracture Union: a randomized and prospective preliminary study. Mol Ther. 2013;21(8):1631–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Labibzadeh N, Emadedin M, Fazeli R, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells implantation in combination with platelet lysate product is safe for reconstruction of human long bone nonunion. Cell J. 2016;18(3):302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ojeda AG. Bone regeneration with mesenchymal stem cells. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02755922 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 38. Muthian S, Sundararaj GD, Lee VN. Percutaneous autologous bone marrow injection in fracture healing. Orthopaedic Proceedings The British Editorial Society of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2008:337–337. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murawski CD, Kennedy JG. Percutaneous internal fixation of proximal fifth metatarsal Jones fractures (zones II and III) with Charlotte Carolina screw and bone marrow aspirate concentrate: an outcome study in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1295–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mishima H, Sugaya H, Yoshioka T, et al. 2. The effect of combined therapy, percutaneous autologous concentrated bone marrow grafting and low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS), on the treatment of Non-Unions. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(8):S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Memeo A, Panuccio E, Verdoni F. In-Depth oral presentations and oral communications. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10195-013-0258-7 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 42. Mannelli G, Arcuri F, Conti M, Agostini T, Raffaini M, Spinelli G. The role of bone marrow aspirate cells in the management of atrophic mandibular fractures by mini-invasive surgical approach: single-institution experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45(5):694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim S-J, Shin Y-W, Yang K-H, et al. A multi-center, randomized, clinical study to compare the effect and safety of autologous cultured osteoblast(Ossron) injection to treat fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jäger M, Jelinek EM, Wess KM, et al. Bone marrow concentrate: a novel strategy for bone defect treatment. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2009;4(1):34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jäger M, Herten M, Fochtmann U, et al. Bridging the gap: bone marrow aspiration concentrate reduces autologous bone grafting in osseous defects. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(2):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ismail HD, Phedy P, Kholinne E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in atrophic nonunion of the long bones. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5(7):287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guimarães JAM, Duarte MEL, Fernandes MBC, et al. The effect of autologous concentrated bone-marrow grafting on the healing of femoral shaft non-unions after locked intramedullary nailing. Injury. 2014;45 Suppl 5(Suppl 5):S7–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gross J-B, Diligent J, Bensoussan D, Galois L, Stoltz J-F, Mainard D. Percutaneous autologous bone marrow injection for treatment of delayed and non-union of long bone: a retrospective study of 45 cases. Biomed Mater Eng. 2015;25(1 Suppl):187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Giannoudis PV, Gudipati S, Harwood P, Kanakaris NK. Long bone non-unions treated with the diamond concept: a case series of 64 patients. Injury. 2015;46 Suppl 8(Suppl 8):S48–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Giannoudis PV, Ahmad MA, Mineo GV, Tosounidis TI, Calori GM, Kanakaris NK. Subtrochanteric fracture non-unions with implant failure managed with the "Diamond" concept. Injury. 2013;44 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S76–S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Garnavos C, Mouzopoulos G, Morakis E. Fixed intramedullary nailing and percutaneous autologous concentrated bone-marrow grafting can promote bone healing in humeral-shaft fractures with delayed Union. Injury. 2010;41(6):563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Garnavos C. Intramedullary nailing with a Suprapatellar approach and condylar bolts for the treatment of Bicondylar fractures of the tibial plateau. JB JS Open Access. 2017;2(2):e0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ebraheim NA, Buchanan GS, Liu X, et al. Treatment of distal femur nonunion following initial fixation with a lateral locking plate. Orthop Surg. 2016;8(3):323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Desai P, Hasan SM, Zambrana L, et al. Bone mesenchymal stem cells with growth factors successfully treat Nonunions and delayed unions. Hss J. 2015;11(2):104–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Denaro V, Di Martino A, Vadala G, et al. Iliac crest harvested bone marrow centrifugate, allograft and platelet derived gel in trauma: our experience with a technique of intraoperative tissue engineering. In-Depth Oral Presentations and Oral Communications. 2011:89–123. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dallari D, Rani N, Sabbioni G, Mazzotta A, Cenacchi A, Savarino L. Radiological assessment of the PRF/BMSC efficacy in the treatment of aseptic nonunions: a retrospective study on 90 subjects. Injury. 2016;47(11):2544–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gouse & Cherian Blood and blood products in treatment of bone healing related to fractures. Clinical Trials Registry - India. 2007. http://ctri.nic.in (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 58. Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Heyberger C, Bouthors C, et al. Osteogenic progenitors in bone marrow aspirates have clinical potential for tibial non-unions healing in diabetic patients. Int Orthop. 2016;40(7):1375–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Castillo-Cardiel G, López-Echaury AC, Saucedo-Ortiz JA, et al. Bone regeneration in mandibular fractures after the application of autologous mesenchymal stem cells, a randomized clinical trial. Dent Traumatol. 2017;33(1):38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Carney D, Chambers MC, Kromka JJ, et al. Jones fracture in the elite athlete: patient reported outcomes following fixation with BMAC. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(7_suppl4):2325967118S:2325967118S0016. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Calori GM, Colombo M, Mazza E, et al. Monotherapy vs. polytherapy in the treatment of forearm non-unions and bone defects. Injury. 2013;44 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S63–S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bhattacharjee A, Kuiper JH, Roberts S, et al. Predictors of fracture healing in patients with recalcitrant nonunions treated with autologous culture expanded bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Orthop. Res.. 2019;37(6):1303–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bastos Filho R, Lermontov S, Borojevic R, Schott PC, Gameiro VS, Granjeiro JM. Cell therapy of pseudarthrosis. Acta Ortop Bras. 2012;20(5):270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Berger M. Osseous setting improvement with Co-implantation of osseous matrix and mesenchymal progenitors cells from autologous bone marrow. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2009. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT00557635 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 65. Rozen N. Enhancement of bone regeneration and healing in the extremities by the use of autologous BonoFill-II. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT03024008 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 66. Hadassah Medical Organization Mononucleotide autologous stem cells and demineralized bone matrix in the treatment of non Union/Delayed fractures. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01435434 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 67. Dilogo I. Allogenic mesenchymal stem cell for bone defect or non Union fracture (AMSC). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02307435 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 68. Segur JM. Allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in elderly patients with hip fracture. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02630836 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 69. peivandi mohammadtaghi. Evaluation the treatment of nonunion of long bone fracture of lower extremities (femur and tibia) using mononuclear stem cells from the iliac wing within a 3-D tissue engineered scaffold. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01958502 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 70. Lee P-Y. Autologous bone marrow concentration for femoral shaft fracture Union. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT03794622 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 71. Qu Z, Fang G, Cui Z, Liu Y. Cell therapy for bone nonunion: a retrospective study. Minerva Med. 2015;106(6):315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Royan Institute Autologous BM-MSC transplantation in combination with platelet lysate (PL) for nonunion treatment. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02448849 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 73. Richardson J. Autologous stem cell therapy for fracture non-union healing. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02177565 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 74. Marsh D. Using autologous mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) to treat human fractures. ISRCTNregistry. 10.1186/ISRCTN09755245 (date last accessed 8 September 2020). [DOI]

- 75. Aghdami N. evaluation of efficacy and side effects of implantation of bone marrow- derived mesenchymal stromal cells in combination with platelet lysate product in reconstruction of human nonunion of tibia fractures/a phase2 & 3 clinical trial. Clinical Trial Protocol Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials. https://en.irct.ir/trial/32 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 76. Le Nail L-R, Stanovici J, Fournier J, Splingard M, Domenech J, Rosset P. Percutaneous grafting with bone marrow autologous concentrate for open tibia fractures: analysis of forty three cases and literature review. Int Orthop. 2014;38(9):1845–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lareau CR, Hsu AR, Anderson RB. Return to play in national football League players after operative Jones fracture treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(1):8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hernigou P, Trousselier M, Roubineau F, et al. Local transplantation of bone marrow concentrated granulocytes precursors can cure without antibiotics infected nonunion of polytraumatic patients in absence of bone defect. Int Orthop. 2016;40(11):2331–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hernigou P, Poignard A, Beaujean F, Rouard H. Percutaneous autologous bone-marrow grafting for nonunions. Influence of the number and concentration of progenitor cells. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1430–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hernigou P, Guissou I, Homma Y, et al. Percutaneous injection of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for ankle non-unions decreases complications in patients with diabetes. Int Orthop. 2015;39(8):1639–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hernigou P, Desroches A, Queinnec S, et al. Morbidity of graft harvesting versus bone marrow aspiration in cell regenerative therapy. Int Orthop. 2014;38(9):1855–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Royan Institute Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in tibial closed diaphyseal fractures. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02140528 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 83. Gómez-Barrena E, Rosset P, Gebhard F, et al. Feasibility and safety of treating non-unions in tibia, femur and humerus with autologous, expanded, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells associated with biphasic calcium phosphate biomaterials in a multicentric, non-comparative trial. Biomaterials. 2019;196:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gómez-Barrena E, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Avendaño-Solá C, et al. A multicentric, open-label, randomized, comparative clinical trial of two different doses of expanded hBM-MSCs plus biomaterial versus iliac crest autograft, for bone healing in nonunions after long bone fractures: study protocol. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018(2):6025918–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Delclos LO, Soler Rich R. Cell therapy applied to the locomotor system. Conferences Institut de Ter pia Regenerativa Tissular (ITRT)”-Centro Médico Teknon, 2010:S23. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Colombo M, Mazza E, Malagoli E, Mazzola S, Calori GM. In-depth oral presentations and oral communications - S18. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014;15(Suppl 1):1–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chu W, Wang X, Gan Y, et al. Screen-enrich-combine circulating system to prepare MSC/β-TCP for bone repair in fractures with depressed tibial plateau. Regen Med. 2019;14(6):555–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fernandez-Bances I, Perez-Basterrechea M, Perez-Lopez S, et al. Repair of long-bone pseudoarthrosis with autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells combined with allogenic bone graft. Cytotherapy. 2013;15(5):571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Emadedin M, Labibzadeh N, Fazeli R, et al. Percutaneous autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell implantation is safe for reconstruction of human lower limb long bone atrophic nonunion. Cell J. 2017;19(1):159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jimenez M, Goulet J, Lyon T N. Feasibility study of Aastrom tissue repair cells to treat non-union fractures. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT00424567 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 91. South China Research Center for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Safety and exploratory efficacy study of UCMSCs in patients with fracture and bone nonunion. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02815423 (date last accessed 8 September 2020).

- 92. Jiang Z-K, Zhou B-H, Chen F-Q, et al. Percutaneous subperiosteum injection of osteoblasts for the treatment of delayed fracture healing and bone nonunion: an analysis of 26 cases. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Research. 2009;13(15):2988–2990. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mojaver A. Effects of 3D scafold containing BMD cells for treatment of femoral and tibial nonunion. Clinical Trial Protocol Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial. [Google Scholar]

- 94. A phase I-II clinical trial to assess the effect of HC-SVT-1001 in the surgical treatment of nonunions fractures of long bones Eu clinical trials register. 2013. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2013-000930-37/ES

- 95. Clinical Trial phase I-II Multicentic of the application of TRC in the surgical treatment of Non-Hypertrophic pseudoarthrosis and complex fractures of long bones Ensayo Clínico Fase I-II, multicéntrico de la Aplicación de las TRC* en El Tratamiento Quirúrgico de Pseudoartrosis no Hipertróficas Y Fracturas Complejas de Huesos Largos *Células Progenitoras de Médula Ósea Autóloga expandidas Con El sistema AastromReplicell TM. EU clinical trials register. 2005. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2005-001755-38/ES

- 96. mohammad taghi peivandi The efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells for stimulate the Union in treatment of Non-united tibial and femoral fractures in Shahid Kamyab Hospital. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01788059

- 97. Gan Y. A randomized controlled clinical trial of rapidly prepared bioactive materials as bone graft using bone marrow stem cells screen-and-enrich-and-combine(-biomaterials) circulating system(SECCS) versus autologous bone graft for bone regeneration. Chinese Clinical trial Registry. 2016. http://www.chictr.org.cn/hvshowproject.aspx?id=10517

- 98. Dallari D, Rani N, Del Piccolo N, Stagni C, Carubbi C, Giunti A. Treatment of long bone nonunion using bone grafting, autologous bone marrow stromal cells and platelet gel. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(1):23–88. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rampoldi M, Viscito R, Atrophic forearm nonunion: Analysis on 44 cases . In-Depth Oral Presentations and Oral Communications. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S47–S82. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mondanelli N, De Biase P, Cuomo P, et al. Diaphyseal and metaphyseal nonunions treated with bone morphogenetic protein BMP-7 and autologous bone-marrow concentrate. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(1):23–88. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Donati DM, Cevolani L, Frisoni T, et al. The use of the demineralized bone matrix (DBM), platelet rich fibrin (Prf) and bone marrow concentrated (BMC) increases healing in patients with non-union. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(1):23–88. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Thua THL, Bui DP, Nguyen DT, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cells combined with allograft cancellous bone in treatment of nonunion. Biomed Res Ther. 2015;2(12). [Google Scholar]

- 103. Giannotti S, Trombi L, Bottai V, et al. Use of autologous human mesenchymal stromal cell/fibrin clot constructs in upper limb non-unions: long-term assessment. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e73893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Beguin Treatment of atrophic nonunion fractures by autologous mesenchymal stem cell percutaneous grafting. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01429012

- 105. Whelan DB, Bhandari M, Stephen D, et al. Development of the radiographic Union score for tibial fractures for the assessment of tibial fracture healing after intramedullary fixation. J Trauma. 2010;68(3):629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lane JM, Sandhu HS. Current approaches to experimental bone grafting. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18(2):213–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Tiedeman JJ, Lippiello L, Connolly JF, Strates BS. Quantitative roentgenographic densitometry for assessing fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;253:279???286–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Killington K, Mafi R, Mafi P, Khan WS. A systematic review of clinical studies investigating mesenchymal stem cells for fracture non-union and bone defects. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;13(4):284–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Imam MA, Holton J, Ernstbrunner L, et al. A systematic review of the clinical applications and complications of bone marrow aspirate concentrate in management of bone defects and nonunions. Int Orthop. 2017;41(11):2213–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Dominici M, Nichols K, Srivastava A, et al. Positioning a scientific community on unproven cellular therapies: the 2015 International Society for cellular therapy perspective. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(12):1663–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Beane OS, Fonseca VC, Cooper LL, Koren G, Darling EM. Impact of aging on the regenerative properties of bone marrow-, muscle-, and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Narbonne P. The effect of age on stem cell function and utility for therapy. Cell Med. 2018;10(3):2155179018773756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, et al. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: the International Society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7(5):393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Dugué AE, Pulido M, Chabaud S, Belin L, Gal J. How to deal with Interval-Censored data Practically while assessing the progression-free survival: a step-by-step guide using SAS and R software. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(23):5629–5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Morris R, Pallister I, Trickett RW. Measuring outcomes following tibial fracture. Injury. 2019;50(2):521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Corrales LA, Morshed S, Bhandari M, Miclau T. Variability in the assessment of fracture-healing in orthopaedic trauma studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(9):1862–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Goldhahn J, Scheele WH, Mitlak BH, et al. Clinical evaluation of medicinal products for acceleration of fracture healing in patients with osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;43(2):343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sheehan WJ, Williams MA, Paskins Z, et al. Research priorities for the management of broken bones of the upper limb in people over 50: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e030028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Chevance A, Tran V-T, Ravaud P. Controversy and debate series on core outcome sets. paper 1: improving the generalizability and credibility of core outcome sets (COS) by a large and international participation of diverse stakeholders. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020(125):206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Yordanov Y, Dechartres A, Atal I, et al. Avoidable waste of research related to outcome planning and reporting in clinical trials. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Board on Health Sciences Policy, Board on Life Sciences, Division on Earth and Life Studies, Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences Comparative regulatory and legal frameworks: National Academies Press (US), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 124. Sleeboom-Faulkner M, Chekar CK, Faulkner A, et al. Comparing national home-keeping and the regulation of translational stem cell applications: an international perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]