Abstract

Introduction:

As COVID-19 develops around the world, numerous publications have described the psychiatric consequences of this pandemic. Although clinicians and healthcare systems are mainly focused on managing critically ill patients in an attempt to limit the number of casualties, psychiatric disease burden is increasing significantly. In this scenario, increased domestic violence and substance abuse have been recently reported.

Objective:

The objective of this study is to perform a systematic review of the literature regarding the consequences of severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV-2 infection in terms of domestic violence and substance abuse, and compare incidences found.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a literature search using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines. The keywords included “domestic violence,” “substance abuse” AND “COVID-19,” including multiple variants from December 2019 through June 2020. An extensive bibliographic search was carried out in different medical databases: Pubmed, EMBASE, LILACS, medRxiv, and bioRxiv. Titles and abstracts were reviewed according to the eligibility criteria. The risk of bias in the retrieved articles was assessed by the Joanna Briggs Institute's critical assessment instrument.

Results:

A total of 1505 papers were initially retrieved after consulting the selected databases. After browsing through titles and abstracts, 94 articles were initially included considering the predefined eligibility criteria. After a more detailed analysis, only six scientific articles remained in our selection. Of these, three were evaluating domestic violence against children, while the other three were about substance abuse.

Conclusion:

There is not enough evidence to support the concept that COVID-19 has led to an increase in the rates of domestic violence and substance abuse. The initial decrease in violence reports might not translate into a real reduction in incidence but in accessibility. Apparently, there has been a slight increase in alcohol and tobacco abuse, especially by regular users, which also requires confirmatory studies. The inconsistency between expert opinon articles and the actual published data could be a result of the limited time since the beginnging of the crisis, the fact that psychitaric patients have been chronically exposed to stressful situatons, and a possible stimulated increase in demand for psychatric consultations.

Keywords: Alcohol drinking, coronavirus infection, COVID-19, domestic violence, social isolation, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has shocked the world with unprecedented consequences in different health and economic aspects.[1] As it develops around the world, numerous publications have described its psychiatric consequences.[2,3,4] Although clinicians and health-care systems are mainly focused on managing critically ill patients in an attempt to limit the number of casualties, psychiatric disease burden is increasing significantly.[5,6] In this scenario, greater substance abuse and increased domestic violence are expected, according to experience obtained from the previous natural catastrophes.[7,8] It has also been postulated that social distancing and quarantines might be an additional contributor to the aggravation of such conditions.[9]

Domestic violence is often defined as physical or emotional violence that might encompass intimate partner violence, elderly violence, child abuse, and pet abuse.[10] It affects many individuals, regardless of age and represents the leading cause of feminicide. It is known that domestic violence has several long-term consequences, being a risk factor numerous mental health conditions such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance or alcohol abuse.[11] It has also been demonstrated that exposure to violence during young years either active or passive is detrimental to mental and physical health and increases the odds of self-harm or suicidal ideation in the future.[10,12] There are reports demonstrating that violence in the domestic setting could also be associated with the development of general health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, sleep disturbances, gastrointestinal problems, sexually transmitted infections, and traumatic brain injury.[11]

Substance abuse is usually considered a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a recurring desire to continue taking the drug despite harmful consequences.[13] It is a known fact that substance abuse and its related consequences are a significant public health problem for young adults impacting the society as a whole.[14] It is a prevalent global public health concern with prevalence estimates of 20%–25% of individuals aged 12 or older.[15] Alcohol is the most commonly used substance, with one out of three young adults reporting excessive drinking habits.[16] Dysfunctional alcohol use is one of the most significant medical burdens, while marijuana is the second most used substance and is also often found in victims of fatal automobile accidents, highlighting the potential negative consequences of the drug. In addition, among first-time substance users, about 25% of them use nonmedical psychotherapeutics, 6.3% use inhalants, and 2% use hallucinogens.[16] It contributes to morbidity and mortality in the population of young individuals with significant consequences, including criminality and violence.[16,17]

Therefore, increasing incidence of domestic violence and substance abuse might have a significant impact on public health in the long term. It is essential that these issues receive enough attention from the authorities, while preventive measures be taken to mitigate their potential negative consequences. Although there have been numerous publications evaluating the developments of psychiatric conditions in the midst of COVID-19, many of them are primarily speculative. The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review of the literature regarding the consequences of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV-2 infection in terms of substance abuse and domestic violence, and compare incidences found.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search strategy

We conducted a literature search using preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.[18,19] The virtual scientific information bases consulted were Medline through Pubmed, EMBASE, LILACS, medRxiv, and bioRxiv. We also perfomred search in unpublished evidence and manual search (reference of references). The databases were searched simultaneously and the concepts of AND, OR, NOT, and combinations were applied when searching key terms.

The following search strategy was performed: #1: Substance-related disorders OR drug abuse OR drug dependence OR drug addiction OR substance use disorders OR substance use disorder OR drug use disorder OR substance abuse OR substance abuses OR substance dependence OR substance addiction OR drug habituation OR alcohol-induced disorders OR alcohol-related disorders OR alcoholic intoxication OR alcoholism OR drug overdose OR inhalant abuse OR marijuana abuse OR narcotic-related disorders OR opioid-induced constipation OR opioid-related disorders; #2: Domestic violence OR child abuse OR elder abuse OR spouse abuse; #3: COVID OR COV OR coronavirus OR SARS; #4: #1 AND #2; #5: #1 AND #3; #6: #2 AND #3; #7: #4 OR #5 OR #6; #8: #7 AND Filters: From 2019 to 2020.

Study selection

The following eligibility criteria for the articles included were considered: (a) World population exposed to substance abuse (alcohol or other legal or illegal drugs) and/or domestic violence, during COVID-19; (b) study design: Case series, observational studies (case-control, cross-sectional, or cohort); (c) time period limited from December 2019 to June 2020; (d) languages limited to English, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian; (e) full text summary with data available for review.

The retrieved studies were initially accessed by title and abstract, and in view of the eligibility criteria, their full texts were consulted. The data collected from the selected studies were inserted to appropriate spreadsheets for the later description and analysis of the results.

Data extraction and synthesis

The extracted data were described by means of prevalence expressed by absolute numbers and percentages. The main outcome measures were the prevalence or incidence rates of aggression or domestic violence, especially to vulnerable groups, and abuse of alcohol, other legal, or illegal drugs. The confidence level was set at 95%. The risk of bias in the case series was assessed by the Joanna Briggs Institute's critical assessment instrument.

RESULTS

Characteristics of selected studies

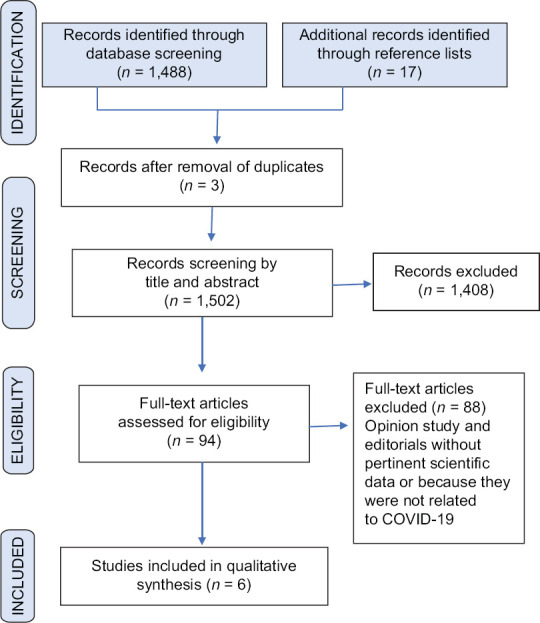

A total of 1,505 papers were initially retrieved after consulting the selected databases [Figure 1]. After browsing through titles and abstracts considering the predefined eligibility criteria, 94 papers were initially considered eligible. After a more detailed analysis, we were left with six scientific articles [Tables 1 and 2]. Of these, three were evaluating domestic violence, while the other three were about substance abuse. Violence against children was the subject of three articles. One of these articles consisted of a documentary from the Chicago Police Department evaluating the number of arrests in residential areas during COVID-19, which analyzed a more comprehensive concept of domestic violence during the Pandemic. All the articles about substance abuse evaluated alcohol consumption, and only one also looked at the change in smoking habits.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review

Table 1.

Selected articles for domestic violence

| Author/year/country | Journal | Methods | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Sample | |||

| Bhopal, et al./2020/England | Arch Dis Child | Documentary | n=407 (152 assessments in 2018; 156 assessments in 2019; 99 assessments in 2020) | The 28 assessments from child protective services done in March 2020 was lower than in 2018 (36 assessments) or 2019 (43 assessments). This was drastically lower in April 2020 after institution of ‘lockdown’ when there were only 13 assessments compared with 50 in April 2018 and 30 in April 2019. The total number of assessments from January to April was 152 in 2018, 156 in 2019 and 99 in 2020, a reduction of approximately one third |

| Molly and McLay/2020/Saint Louis | MedRxiv | Documentary study collected from the Chicago Police Department | n=4.618 | During the pandemic period, cases with arrests were 3% less likely to have occurred, and cases at residential locations were 22% more likely to have occurred. During the shelter-in-place period, cases at residential locations were 64% more likely to have occurred, and cases with child victims were 67% less likely to have occurred |

| Sidpra J, Abomeli D, Hameed/2020/London | Arch Dis Child | Cross-seccional | n=10 children (six boys, four girls) | This equates to a 1493% Increase in cases of abusive head trauma. All families live in areas with a higher than average Index of Multiple Deprivation (national mean 15 200; cohort mean 19 867), and 70% of parents had significant underlying vulnerabilities: two had previous criminal histories, three had mental health disorders, and four had financial concerns |

Table 2.

Selected articles for substance abuse

| Author/year/country | Journal | Methods | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Sample | |||

| Balhara1 et al./2020 | Psychiatry Clin Neurosci | Cross-seccional | n=73 men | The average duration of alcohol use disorder was 8.66 (SD 6.20) years. Twenty percent (16) related to alcohol consumption during confinement. Ten of them (62.5%, n=16) managed to acquire the same at least once. Five patients (6.6%) reported abstinence from alcohol since the beginning of the block. In the binary logistic regression model, days since the last use of alcohol (OR 0.90 [0.84-0.97], P=0.007) was the only variable independently associated (inverse association) to the attempt to seek alcohol during the blocking period |

| Chodkiewicz, et al./2020/Poland | Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health | A longitudinal study | n=443 (78.6% women and 21.4% men) | Alcohol was the most commonly used psychoactive substance (73%) identified. More than 30% changed their drinking habits because of the pandemic, with 16% actually drinking less, whilst 14% did so more. The former group was significantly younger than the latter. Amongst the stress-related coping strategies, it was found that current alcohol drinkers were significantly less able to find anything positive about the pandemic situation (positive reframing) and were mentally less able to cope. Those drinking more now were found to have been drinking more intensively before the pandemic started |

| Yan Sun, et al./2020/Beijing, China | The American Journal on Addictions | Cross-sectional (survey/self-report questtionaire) | n=6416 (47% males and 53% females) | The overall rate of alcohol drinking and smoking among the 6416 participants increased only marginally during the COVID-19 pandemic from 31.3% (n=2006) to 32.7% (n=2098) for drinking and from 12.8% (n=822) to 13.6% (n=873) for smoking. However, addictive behaviors increased substantially in two areas: (a) 18.7% of 331 ex-drinkers and 25.3% of 190 ex-smokers had relapsed; (b) 32.1% of 137 regular drinkers and 19.7% of 412 regular smokers reported an increased amount of alcohol drinking or cigarette smoking |

SD – Standard deviation; CI – Confidence interval

Most of the excluded manuscripts were mainly opinion-based articles discussing theories but without scientific data. Other excluded papers had data, but the timeframe was not within the preestablished criteria or were not related to COVID-19. All selected articles consisted of reports of noncontrolled case series. The quality of the evidence was classified as very low due to the design of clinical research. However, biases risk assessment regarding these studies considered them as low risk for bias.

DISCUSSION

Since there is an escalating preoccupation with acquiring a potentially deadly infectious disease associated with job insecurity and social isolation, it is only expected that the psychiatric burden of the pandemic will increase.[20] It has already been reported that anxiety levels have increased significantly, with a potential compromise of mental health.[4] However, this systematic review examined only six studies published during the times of COVID-19. The paucity of high-quality data analyzing the consequences of the pandemic has prevented us from drawing more definitive conclusions. It is a fact that since the outbreak of the coronavirus crisis, there have been numerous publications analyzing its health and psychiatric consequences.[21,22,23,24,25] However, this article has highlighted that most of these publications are not data-driven and mostly based on expert opinion and experience from previous epidemics.

There might be numerous explanations for this inconsistency between expert opinon and the actual published data. First, the aumont of time in whch all these global health issues have developed is relatively short. Studies from previous natural catastrophes have estimated that it should take at least 1 year for a more profound understanding of the postpandemic phenomena.[9,21] Therefore, the scientific community will definitely need more time so that more well-desgined studies with a more robust patient population are published. Another important issue to take into account is that individuals at risk for domestic violence and substance abuse are chronically exposed to elevated anxiety levels, highly stressful enviroments and unfavorable economic situations. In such vulnerable populations, the current aggravation could be less impactful. Finally, the high demand for psychiatric evaluation and follow-up during COVID-19 might have led mental health professionals to overestimate its psychiatric impact. As a significant proportion of the population had to abstain from work, it has become more convenient to search for medical consultations. Not to mention the development of recommendations and the creation of mechanisms that stimulate notification and help-seeking behavior by psychiatric patients and family members.

Regardless of the chaotic scenario brought about by COVID-19, domestic violence has always been a matter of public health. The long-term adverse effects of domestic violence are well established.[26,27,28] Furthermore, natural disasters are expected to generate the family violence risk factors such as an increase in anxiety and stress, the sudden change in routine, unemployment, the closing of schools, decrease in access to coping resources, among others.[9] The fact is that some individuals find themselves confined with their aggressors with limited contact to their supporting environment.[8,9,20] Studie s have shown that while other forms of violent crime may or may not be influenced by global epidemics, domestic violence often reports substantially increase after the catastrophic event.[7,9]

One of the studies included in our review has reported that there was a 3% decrease in arrests during the Pandemic. During the lockdown period, police occurrences at residential locations in the Chicago area were 64% more likely to have occurred, while cases involving child violence were 67% less likely to have occurred.[29] Another study has performed a comparative assessment of child protective services in the past years.[30] The authors have demonstrated that the use of this service was significantly reduced in March 2020 in comparison with the two previous. Moreover, the number of requirements of this service was lowest during lockdown that happened in April 2020, with a reduction of approximately 33%. In contrast, a British study has shown a significant increase in abusive head trauma in children, although 70% of parents had significant underlying vulnerabilities, including prior criminal histories.[31]

This controversy has already been acknowledged. Many child welfare organizations have mentioned a significant decrease in reports of child abuse or neglect. However, it has been hypothesized that this drop could be a consequence of restricts opportunities for detection rather than real describes in violence. The closure of schools and other essential community resources has limited the overall ability to detect and report different kinds of abuse toward children.[13] Other forms of violence, including intimate partner violence, elder violence, or pet violence, have not been reported yet, limiting the ability to make considerable statements.

Regarding substance abuse, the published studies included in the current review have focused solely on alcohol and tobacco consumption. Other illicit drugs and prescription medication, which could also be potentially affected by the Pandemic, have not been evaluated at this time. Although abusers of different substances tend to share similar risk factors, it is not possible to extrapolate the current findings.

A longitudinal study evaluating 442 individuals demonstrated that alcohol was the most commonly reported psychoactive substance consumed by participants (73%). The authors revealed that over a third of participants changed their drinking habits during the Pandemic: Sixteen percent reported drinking less while 14% admitted to drinking more often. Interestingly, those drinking more were found to have been drinking more intensively even before the Pandemic started.[32] In a cross-sectional study with 73 individuals with a previous history of alcohol abuse, Balhara et al. have found that 20% of them admitted to alcohol consumption. Days since the last use of alcohol was the only variable that demonstrated an independent and inverse association to the attempt to alcohol consumption during times of COVID-19 (odds ratio 0.90; 95% confidence interval 0.84–0.97, P = 0.007) in a logistic regression model.[33] Another study included in this review assessed 6416 participants during COVID-19 and found that the overall rate of alcohol and tobacco had only a slight increase. According to the authors, rates went from 31.3% to 32.7%, for drinking and from 12.8% to 13.6% for smoking.[34] In this study, there was indications of addictive behavior, in which known users reported an increased intake, and there was a significant relapse from ex-users (18% for drinkers and 25% for smokers).[34]

This systematic review is not without limitations. As previously mentioned, our main limitation is the low quality of studies found in our literature search. This fact has prevented us from having a more transparent overview of the studied phenomena. On the other hand, we have performed a well-designed review with preestablished scientific questions and a sound methodology. We have strictly followed the PRISMA guidelines. Moreover, we have also search for databases with prepeer-reviewed papers, which could potentially mitigate the publication bias.

CONCLUSION

There is not enough evidence to support the concept that COVID-19 has irrefutably led to an increase in the rates of domestic violence and substance abuse. Because it is a very new situation, published studies lack more robust designs being limited to editorials and cross-sectional studies. There is no irrefutable evidence demonstrating an increase in cases of domestic violence. The initial decrease in violence reports, might not translate into a real reduction in incidence but in accessibility. Apparently, there has been a slight increase in alcohol and tobacco abuse, especially by regular users, which also requires confirmatory studies.

The inconsistency between expert opinon articles and the actual published data about the psychiatric impact of COVID-19 could be a result of the limited time since the beginnging of the crisis, the fact that psychitaric patients have been chronically exposed to stressful situatons, and a possible stimulated increase in demand for psychatric consultations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diab Metab Syndrome. 2020;14:779–88. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lima CK, Carvalho PM, Lima IA, Nunes JV, Saraiva JS, de Souza RI, et al. The emotional impact of coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease) Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112915. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L, et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1732–8. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM. 2020:hcaa202. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson D. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: An australian case study. J Interpers Violence. 2019;34:2333–62. doi: 10.1177/0886260517696876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerna-Turoff I, Fischer HT, Mayhew S, Devries K. Violence against children and natural disasters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative evidence. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;2:100089. doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazza M, Marano G, Lai C, Janiri L, Sani G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113046. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Serag R, Thurston RC. Matters of the heart and mind: Interpersonal violence and cardiovascular disease in Women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015479. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.015479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke A, Olive P, Akooji N, Whittaker K. Violence exposure and young people's vulnerability, mental and physical health. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:357–66. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01340-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou Z, Wang H, d'Oleire Uquillas F, Wang X, Ding J, Chen H. Definition of substance and Non-substance addiction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1010:21–41. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5562-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shillington AM, Woodruff SI, Clapp JD, Reed MB, Lemus H. Self-reported age of onset and telescoping for cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana across eight ears of the national longitudinal survey of youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21:333–48. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.710026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Howard MO, Garland EL, McGovern P, Lazar M. Mindfulness treatment for substance misuse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:62–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazemi DM, Borsari B, Levine MJ, Li S, Lamberson KA, Matta LA. A systematic review of the mHealth interventions to prevent alcohol and substance abuse. J Health Commun. 2017;22:413–32. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1303556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jutras-Aswad D. Substance use and misuse: Emerging epidemiological trends, new definitions, and innovative treatment targets. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:134–5. doi: 10.1177/0706743716632513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, Moher D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and extensions: A scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:263. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0663-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warburton E, Raniolo G. Domestic abuse during COVID-19: What about the boys? Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113155. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–60. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang YT, Zhao YJ, Liu ZH, Li XH, Zhao N, Cheung T, et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: Managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1741–4. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai YL, Ren L, He N. The effects of domestic violence on violent prison misconduct, health status, and need for post-release assistance among female drug offenders in Taiwan. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2018;62:4942–59. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18801487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang LHG, Thomas SJ. Exposure to domestic violence during adolescence: Coping strategies and attachment styles as early moderators and their relationship to functioning during adulthood. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2020;13:185–98. doi: 10.1007/s40653-019-00279-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor J, Bradbury-Jones C, Lazenbatt A, Soliman F. Child maltreatment: Pathway to chronic and long-term conditions? J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:426–31. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLay MM. When “Shelter-in-Place” Isn't Shelter That's Safe: A rapid analysis of domestic violence case differences During the COVID-19 Pandemic and stay-at-home orders medRxiv. 2020. Available from: https://wwwmedrxivorg/content/101101/2020052920117366v1fullpdf . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bhopal S, Buckland A, McCrone R, Villis AI, Owens S. Who has been missed Dramatic decrease in numbers of children seen for child protection assessments during the pandemic. Arch Dis Child. 2020 Jun 18; doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319783. archdischild-2020-319783 doi: 101136/archdischild-2020-319783 Epub ahead of print PMID: 32554510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidpra J, Abomeli D, Hameed B, Baker J, Mankad K. Rise in the incidence of abusive head trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. 2020 Jul;2:archdischild. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319872. doi: 10.1136/ Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32616522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chodkiewicz J, Talarowska M, Miniszewska J, Nawrocka N, Bilinski P. Alcohol Consumption Reported during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Initial Stage. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 29;17(13):4677. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134677. doi: 10.3390/ijerph1713 PMID: 32610613; PMCID: PMC7369979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balhara YP, Singh S, Narang P. Effect of lockdown following COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol use and help-seeking behavior: Observations and insights from a sample of alcohol use disorder patients under treatment from a tertiary care center. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:440–1. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Y, Li Y, Bao Y, Meng S, Sun Y, Schumann G, et al. Brief report: increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Am J Addict. 2020;29:268–70. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]