Abstract

The current global health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, has posed an unprecedented challenge to our health systems, economy, socio-political organizations, and the infrastructure of most countries and the world. This pandemic has affected physical health as well as mental health adversely. Several recent evidence suggests that health systems across the world have to improve their preparedness in context to infectious pandemics. The research on mental health aspects of COVID-19 and other related pandemics is lacking due to obvious reasons. This narrative review article, along with our personal views, is on various current and future mental health issues in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic focusing on various challenges and suggested solutions. The aim is also to update mental health strategies in the context of such rapidly spreading contagious illness, which can act as a resource for such a situation, currently and in future. We recommend that there is a need to facilitate mental health research to understand the psychiatric aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, include psychiatrists in the task force, and make available psychotropic and other medications with special attention to the deprived sector of the society.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, pandemic

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus pandemic is a global threat in the 21st century. Over the last 3 months, there has been a significant rise in the number of infected cases and mortality due to this infection. The coronavirus epidemic started from the Wuhan city of China and has subsequently spread across the globe.[1] It has been seen over the past few months that the routine health services, including mental health care, are adversely affected in many countries, including India. At the same time, several lay media reports are suggesting an increase in mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress-like symptoms, insomnia, and anger among the general population, health workers, as well as people who are kept in isolation (due to infection with coronavirus or contact with infected persons).[2] The rapidly emerging mental health issues may destabilize individuals' general well-being and have immense potential to influence the health system; hence, they need urgent and immediate attention and action. The community's mental health issues can be diverse and segregated as per the specific group of population. There are several risk factors that attribute to the development of psychological symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [Table 1].

Table 1.

Tentative list of risk factors for the development of psychological symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Type | Risk factor |

|---|---|

| Biological | Female gender[10,11,12] |

| Children[13] | |

| Elderly[14] | |

| Physical comorbidities[10] | |

| Family history of psychiatric illness[11] | |

| Social | Low socioeconomic status[10,15] |

| Students[10] | |

| Living alone[10,15] | |

| Physical attributes like a China-man[16] | |

| Lack of resources for recreation[10] | |

| Poor psychosocial support[17] | |

| Psychological | Previous poor mental health status[18] |

| Diagnosed cases of anxiety/depression[10] | |

| Bereavement of a loved one[19] | |

| Poor coping reserves[9,20] | |

| Economical | Poor economic condition[10,15] |

| Loss or potential loss of job[21] | |

| Uncertainties regarding economic conditions[15] | |

| Disease specific | Nonspecific flu symptoms[22] |

| Characteristics of COVID-19 | Rapidly spreading infection with the potential of serious illness and death[22] |

| Lack of effective treatment strategies[23] | |

| Lack of vaccine[23] | |

| Poor understanding leading to governmental and health-care guidelines[23] |

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES AMONG THE GENERAL POPULATION

Under reasonable stress, anyone can experience mental morbidity symptoms after a traumatic event and pandemics, which are capable of inducing a lot of stress among large populations. Several factors determine the likelihood of a person developing these conditions.[1,3] The conditions that precede the event; the nature of the traumatic event happening; the scenarios after the event; rapidity of event; level of uncertainty involved; the potential for personal risk and risk to the family or loved ones; and the overall impact on the economy, jobs, socio-political organizations, etc., are some of the factors determining the outcome.[4] A recently concluded systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of psychological morbidities among the general population, health-care workers, and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic reported that about half of the population faced psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.[5] Poor sleep quality (40%), stress (34%), and psychological distress (34%) were the most commonly reported problems across various studies.[1] An online Indian survey has reported that about 40.5% of the participants reported anxiety or depressive symptoms. About three-fourth (74.1%) of the participants reported a moderate level of stress, and 71.7% reported poor well-being.[6]

Stress has been invariably associated with precipitation and exacerbation of psychiatric illnesses, and the level of inflammatory cytokines is elevated in these conditions, especially psychosis. It is hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 infection and the stressors arising out of the illness and its related outcomes may increase the risk of developing psychiatric illness by disrupting the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and causing imbalance in glucocorticoid level (increasing cortisol), which subsequently result in immune dysfunction (increase in the cytokine levels).[7]

Generally, when a stressful event occurs, it has been found that certain sections of the population such as females, children, and the elderly are at a higher risk of experiencing difficulties.[8] Pretraumatic factors which could potentiate a psychiatric illness could comprise of past psychiatric illness or irresolvable loss or trauma and a history of sexual exploitation during childhood. Other risk factors are socioeconomic vulnerability, lack of education, and substance abuse. Perhaps not surprisingly, those suffering from other multiple personal problems are far more prone to respond negatively to a major stressful event. The issues suffered by the special populations have been discussed separately in this paper.

Profound psychological responses could be triggered by such incidents, which could comprise a life-safety risk, either actual or imaginary. Therefore, relatively close people to the event are inherently predisposed and may suffer from a greater number of major problems. Increased mental health issues are also impacted by the lack of support and cold responses from others.[9] When combined with a sense of regret and further amplified by a lack of community support or previous social dogmas, psychological distress increases multi-folds.

Psychological markers for posttraumatic stress reactions can be seen in the individual's emotionality, cognition, attitudes, and temperament. Symptoms such as sleep deprivation may also supersede. Some have tachycardia, trembling, sweating and fatigue, tiredness, fever, nonspecific somatic symptoms, and other symptoms of autonomic dysfunction.[3] Regardless of the degree of crisis, strategies must assure that those at risk are detected and provided with the resources they need.[8]

The concept of “hypochondriac concerns” (worry about being infected) can be established as the cause for developing anxiety and depression, the constant fear that the epidemic could be hard to control, with the unknown impacts on personal and social lives. Those who were well versed with precautionary measures, informed with ample material about the illness, tend to do better.

If a comparison is drawn between the psychological impact caused due to different pandemics (SARS, MERS, and Ebola) that occurred in the past, the risk factors remain similar; being, for experiencing anxiety symptoms and anger including symptoms during isolation, inadequate supplies (food, clothes, and accommodation), social networking activities (email, text, and the Internet), history of psychiatric illnesses, and financial loss. For long-term influence on mental health, the prevalence of any psychiatric disorder at 30 months post-SARS was 33.3%. Studies have reported that one-fourth of the patients had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and about 15% had depressive disorders, which included health-care professionals and general people.[5,10]

Increased levels of distress and preoccupation with the disease can be acknowledged due to a constant flow of information through media outlets regarding the spread of diseases.[22,10] Being influenced by the same, people tend to follow the untested treatments and remedies advertised. If they are tried by people with long-term health problems, they can cause more harm than good.[24] The specific mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic are listed below:

Emotional problems include fear, rage, edginess and mood swings, criticism, and blaming (self and others), frustration, depression, emotional numbness, and inability to cope[2,9]

Biological functioning such as impairment in sleep and sexual functioning[25,26]

Cognitive issues include poor concentration, poor memory, inability to make decisions, integrity loss, heightened alertness, perceptual distortions, intrusive and unwelcome memories, reduced self-esteem/confidence, and denial

Psychological and personality issues include emotional outbursts, anger, argumentativeness, and inability to settle. Withdrawal, lack of ability to interact with others, reduction/loss of appetite (or may be increased as a coping mechanism), reduction or loss of libido, inability to regulate substance use, and increased risk-taking behaviors

Variable responses depending on the level of stress perceived can be seen. Somatization often occurs in people who are unable to handle stress. The media portrayal of COVID-19 has led to a state of constant hypervigilance among the people, leading to the development of various somatic symptoms and panic levels of anxiety[27]

Suicides have been reported from various parts of the world concerning the COVID-19 pandemic.[28] The mental health impact of the disease in countries like India and Bangladesh regarding the fear of COVID-19 are seen from the case reports,[28,29] which warrant intervention from the psychiatry fraternity and strengthen protocols for crisis management targeted to the COVID-19 pandemic[29]

Another common phenomenon is paranoia and fear, which is further enhanced by the constant telephonic reminders and flash of news on the contamination of novel coronavirus, which are acting as a source for paranoid ideas[18]

Similar cognitive distortions can lead to obsessive contamination thoughts and can reinforce illness in vulnerable populations[30,31]

Patients with substance use disorder are likely to experience withdrawal symptoms due to lockdown and inaccessibility to substances. Similarly, spending most of the time at home due to lockdown increases the risk of excessive use of the Internet and binge-watching of television, which may later lead to technology addiction.[32,33]

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES OF PATIENTS ALREADY HAVING DIAGNOSED WITH PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESSES

The consequences of infection by a new virus, potentially lethal, can threaten patients with confirmed or suspected 2019-nCoV, and those under quarantine can feel anxiety, alienation, and frustration. In addition to these, symptoms such as fever, hypoxia, and cough, as well as adverse medication effects, such as corticosteroid-insomnia, can contribute to deteriorating anxiety and mental distress.[30,34]

In light of past experiences, as seen in the initial stages of the SARS epidemic in 2003, there was a rise in various psychiatric problems such as chronic depression, terror, panic attacks, psychomotor agitation, psychotic symptoms, delirium, and even suicide. Mandatory contact detection and the period of 14 days of quarantine may exacerbate patients' anxiety.[28,30,35]

A recent online survey from India reported that the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown, and resultant situations led to the marked disruption of mental health service provisions across the country involving brain stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, inpatient services, outpatient services, psychotherapy, etc., Even in services that continued to operate, there was a marked reduction in accessibility and utilization during this period.[36] Thus, feelings of loneliness and helplessness are enhanced by the inability to access health-care facilities and procure medications. The inability to access day-care centers, religious places, and community centers can further exacerbate seclusion and feelings of isolation, which could potentiate depressive symptoms. As the government is advising social distancing to people, for the patients suffering from depression, this can be detrimental. During the isolation period, as the days pass by, there is an increased sense of fear and death propagation among the mentally ill.[4,34,37,38] The widespread fear and anxiety associated with the pandemic may have an extremely negative impact on the mental status of people who are already suffering from anxiety disorders. They would need dose modifications and an increased number of consultations. Due to the inability and difficulties faced while contacting mental health professionals, this can further impact them, which can then increase the risk of iatrogenic drug dependence in patients.[30,39]

Due to social isolation and heightened fear, the mentally ill may face situations where access to therapy is lost. They may be along different stages of therapy, or have terminated it recently; they can feel a sudden enormous change in their lifestyle. Though this may be temporary, they may develop adjustment problems, increasing the burden of mental health issues.[31]

Many patients will face difficulty in the current time due to the loss or breakdown of their coping mechanisms about lockdown conditions, leading to rapidly mounting amounts of anxiety, and when placed in a dysfunctional family system, there may be an increase in the levels of expressed emotions due to increased global stress attributing to the COVID-19 pandemic. This interplay of different factors can lead to tension among the family, impacting all the family members.[7]

Patients with substance use disorders may face crises, especially after relapse, but patients currently under abstinence due to this lockdown can have a beneficial effect on their health, increasing the period of the abstinence and helping them focus on their families and recognizing their family support.[10]

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES AMONG HEALTH-CARE PROFESSIONALS

Health professionals, particularly those at medical facilities that take care of people with 2019-nCoV disease, are susceptible to a higher risk of illness as well as mental health issues. They may even feel afraid of the consequences that the illness could spread to their family, acquaintances, or co-workers.[40] Recent Indian and international studies have reported high rates of mental health-related issues and psychological morbidities.[6,4] The overall rates of psychological morbidities in health professionals were higher than that of the general population.[5] Health-care personnel in a quarantined facility in Beijing, operating with high-risk medical conditions such as SARS or witnessing a family or relative with SARS, had considerably more symptoms of posttraumatic stress than someone without these encounters.[10] Already during the current pandemic, there have been reports of health professionals isolating themselves in the underground garages of their homes, to prevent transmission to their family. The long-term psychological effects of such self-imposed isolation and lack of family contact are currently unknown.[41]

2019-nCoV has been repeatedly portrayed as a “killer virus” by media reports that have perpetuated people's perception of danger and confusion.[8] Many of the health professionals providing care to nCoV patients face discrimination from the society due to perceived carriers of the deadly virus, such as being forced to vacate rented accommodations.[4,10,41] The unavailability of proper personnel protective equipment (PPE) can be a cause of stress among the health-care providers, and international reports regarding the death of health-care providers can trigger fear and negative attitudes among the health-care personnel to provide proactive care to the patients and the community. The proper training in the health-care management of COVID-19 must include mental health management of the staff.[1,42] The training module should include resources and protocols that can help maintain their mental health throughout their working hours and during their quarantine period.[43,44] Some of the interested staff can be trained in crisis intervention and relaxation techniques to act as onsite sources of help.[12] The stigma and perceived burden of mental health care has been the main reason for distress among the people and health professionals.[40,41]

Still, during the times of such grave pandemic, many health-care professionals keep an altruistic attitude for the greater good. Such an approach helps reduce psychological comorbidity and is related negatively to stress levels.[15]

Challenges for health-care professionals

Workforce and resource constraints

Even before the pandemic, there was a global dearth of health workforce throughout the world. India has been struggling to manage their already-burdened health-care system.[45] The current pandemic is a global crisis, which resulted in exhaustion of healthcare resources, worldwide.[46] With the formation of various task forces and procurement of the PPE and public awareness, along with the use of high technology measures, the training is being provided to the people. Some of the Indian states are working together with public and private health-care systems to create mechanisms for fast screening and triage and testing. Armed forces and Railways in India[47] have cooperated and are creating mechanisms for setting up temporary care facilities and providing access to testing and treatment far and wide.[48]

Lack of preparedness

One of the most important challenges regarding COVID-19 was the lack of preparedness. The magnitude of the pandemic was estimated far less during the 1st phase in China, and even after it has declared, there was not enough researches and evidence to manage the problem. This led to a delay in the mobilization of the resources in various countries. The measures taken up for reduction were delayed in various countries, which helped the pandemic reach globally and cause fatalities. Due to the rapidity of spread, the coronavirus pandemic created challenges for the developed countries and developing countries equally, resulting into a lack of supplies for PPE, medicines, sanitizers, hand wash, and other livesaving facilities. The highly pathogenic nature of the illness leads to fast transmission and fatality of the health-care workers, creating issues of burnout and unsafe staffing, endangering the health of all categories of health professionals.[49] The pandemic placed a lot of demand for changing the conventional working style. Teleconsultations, online mediums of working, etc., are being proposed for continued working. Although this led to the maintenance of services, it also placed pressure on many health-care professionals in terms of getting acquainted with the technology, its use, procuring resources, and reorganizing services quite rapidly, specifically on persons who were not very adept to the use of technology earlier.[36]

Fear of contracting an infection from health-care settings

The most common concern among the health-care providers was the risk for cross-infection and contamination of novel coronavirus from the health-care settings. Among the health-care workers, it was found that their main concern was not infecting themselves but effecting their family members and close ones.[50] The public reaction toward health-care professionals also has been not favorable. Due to the fear of contracting the illness from the hospital setting, there have been negative attitudes in the general people as well as health-care professionals.[28,29,35] The effects of quarantine and isolation also associated with adverse mental health issues. Many health workers have perceived it stressful.[41,49]

Scarcity of preventive measures

The illnesses affecting humanity are studied systematically, but when a novel pathogen infection starts rising and spreading in an unprecedented way, there is chaos. The chaotic activities pervade all the areas of social life, workplace, and health of the population. This condition leads to a sudden rise in demand in health care, which had not been thought ahead of leading to scarcities of resources in all aspects (man, money, and material). This leads to a crisis of preventive measures like the case of a novel coronavirus; there are uncertainty and lack of knowledge leading to scarcity of measures available.[51,52,53] There is sudden inflation in the market and an upsurge of panic buying, leading to further scarcity of resources.[54] These issues lead to a scarcity of preventive measures and increase the psychological burden of disease.

Social distancing

The most effective method to prevent COVID-19 is social distancing. The COVID-19 disease spreads through direct human-to-human contact as well as through secondary contacts. This has led to the extensive and rapid spread of the disease throughout large landscapes of the world. Studies have suggested that effective social distancing can bring the curve of infection down significantly if practiced appropriately. Thus, the Nation supported and directed their people to follow social distancing in their daily lives. This measure was difficult to be imposed without strict regulations. Due to increasing fatalities, many countries across the world advanced into lockdowns. Protocols were developed and discussed internationally regarding social distancing. “Handshake” was replaced by “Namaste” and “Bow” to avoid the risk for contact a “Wuhan leg shake” was also instituted to avoid contact. Various studies from time to time have reported that social distancing is an effective way to reduce the transmission of influenza viruses.[22,55] The social-distancing protocol has been instituted in all the essential service areas, including hospitals and emergency care areas. Personal and social functions were asked to be canceled with the social-distancing protocol in place. Further, in order to avoid the infection and bring down the potential cases and fatalities, the social-distancing protocol was advanced into a lockdown of the urban areas, and that progressed to the grounding of the Aircrafts, halting of the Railway services, and stoppage of bus routes into a complete national lockdown. The effects of such measures in the past had proven in the reduction of communicable diseases.[55]

The effects of such measures on the psyche of the people can be profound. Various groups of people had varied responses to the social-distancing protocols.[37] The impact of COVID-19 on mental health has been significantly high. There are varied issues of the stress response, and the global phenomenon has triggered physical as well as psychological issues, thus adding to the burden on the health-care industry.[8]

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES OF PEOPLE AT RISK

People with overseas travel history, people with a history of exposure to COVID-19-positive or suspected cases, or people who have traveled from metropolitans to their native places during the lockdown, are being considered “at risk” patients for COVID-19. They are being advised to either quarantine at a governmental facility, home-self-isolation, or to undergo self-disclosure and testing for COVID-19. A range of reactions is being observed in these situations from proper adherence of advice to complete denial, active resistance, running away from lockdown, or breaking rules of self-isolation. Reasons for such reactions can also be related to the psychological understandings of individuals and the said surroundings. Improper understanding of illness, mode of transmission, and its impact, perceived stigma, lack of adequate understanding between people and administrators, fear, etc., maybe some of the psychological reasons associated. Others could be influence by people around, lack of faith in health facilities and the government, socio-economic status, literacy, and anxiety. There is a high chance for significant psychological stress among these people, stemming from such causes, which can further lead to undue psychiatric morbidities such as anxiety and depression.[23]

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES AMONG SPECIAL POPULATIONS

The mental health of the special populations is at very high risk in the case of COVID-19; within a matter of a few months, the illness affected people globally at a high rate. The demography of the developed countries has been affected very adversely to date.[29] The effect on the special populations due to COVID-19 is a matter of great concern as the natural history of the virus is completely unknown, and it is a novel virus leading to speculations and sporadic observations in certain situations.

-

Elderly: The elderly have been especially at risk regarding morbidity and mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic; they are already at risk due to their preexisting problems:

- Cardiovascular, neuromuscular, and neurocognitive disorders often are burdened by autoimmune disorders and compromised immunity due to lack of proper nutrition and more vulnerable in developing dementia and depression such disorders. In addition to the increased mortality, there are increased chances of psychological distress and exacerbation of the existing mental health conditions.[38] In light of the recent social isolation and enforced lockdowns, the risk of anxiety and depression in the elderly is elevated.[22] COVID-19 requires isolation for the peak hours to stop transmission. Provisions for delivering food and essential supplies to those people can be an essential component of care in the areas, where the elderly live on their own without younger children. Social distancing may affect the elderly in a different way than others as their only social contacts are outside their homes such as day-cares and friends and many may not have their spouse or children living with them. Encouraging community engagement and helping them by providing them their needs, may be useful to overcome from helplessness and hopelessness.[37,39]

Children and adolescents: COVID-19 is a never-before experience for most of the world. Children and adolescents can get affected by the pandemic in a very different way. Younger children may not be able to perceive the social isolation measures applied to them; their schools and play areas have been closed down; and their peer group, friends, sleepovers, and playdates have stopped. This can lead them to develop sadness and feelings of isolation. Children of health-care workers and emergency services may also be stranded home with both parents working, leading to difficulty being at home alone.[41] Children may also be living with the elderly, and both being at risk for infection; the social distancing protocols and lockdowns not only affect their perception of the pandemic but also may increase, fear, anxiety, behavioral abnormalities, irritability, and agitation. Children may be observed to regress and cry, and adolescents may try out substance use to cope. These unhealthy coping mechanisms can lead to the development of short-term and long-term mental health issues.[56,57] Prolonged periods of quarantine among children and adolescents may lead to the development of disorders such as anxiety and depression and may even lead to decreased immunity and development of somatic disorders as well.[44,58] Younger participants (<35 years) were more likely to develop anxiety and depressive symptoms in the pandemic situation.[22] These signs and symptoms were similar to those of a previous study in Taiwan during the SARS outbreak.[59] The average time participants spent focusing on the COVID-19 epidemic, such as watching the news and talking about it each day is a predictor of anxiety. It was found that people who spent too much time focusing on the epidemic (≥3 h) were more likely to develop anxiety symptoms.[56,60] The manifestation of this panic mood may be related to the body's normal protective response to the stress caused by the epidemic[8,51,58]

Pregnant women: Pregnant women are at severe risk from COVID-19 due to the sudden outbreak and unknown natural history of the disease. There has been a dearth of evidence how novel coronavirus can affect the pregnant women throughout the world.[59] The evidence from small-scale studies has reported that women who got infected with COVID-19 disease had mild symptoms and were approaching their time of delivery in the second half of the third trimester, and they had outcomes that were more or less healthy. The increasing duration of the disease will expose women in their early pregnancies to the disease, but there is no documented evidence regarding the use of C-section to deliver babies during the pandemic. The use of drugs in pregnancy requires a lot of testing, be it chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, and the use of corticosteroids has been an issue of serious concern.[61] Even the mental health status of pregnant women pose a grave situation, which should be treated seriously. Women in their initial phase of pregnancy are being exposed to the virus, which may lead to unknown complications and outcomes of pregnancy. Generally, pregnant women need support especially emotional during the times of pregnancy, but the social-distancing protocols may prevent them from the usual social support received by them. The issues are even greater when a woman who is a health-care worker becomes pregnant during such times. This can create undue stress to the already-burdened system and push the women under stress. Similar situations can happen when nuclear families with health-care workers and one of the partners are pregnant. It becomes difficult and puts a lot of burden on the pregnant woman as their spouse might pose a risk for infection for her as well as her unborn child. Mental health help and support from the workplace would be required during such times to provide quarantine and other basic facilities to pregnant women. Online mental health and online midwifery support can help those women tremendously and protect them from the harm of infection and help them maintain their health.

Marginalized communities: The indigenous and tribal people who have been marginalized from the communities also are at great risk, they usually do not have access to health-care needs and live in places where sanitary measures and health services are hard to reach during the normal times. COVID-19 can become a very big challenge to provide for such communities. The majority of such people work in jobs that are unsafe and are unable to avail paid leaves and face threat of eviction they may lose work and place to stay which makes them more vulnerable to the disease and push them toward mental ill-health. They may come across issues such as helplessness, hopelessness, and maybe forces to beg for essential sustainability.[62] The lockdown in India also has its impacts on the migrant labor populations, and people were forced to take very risky steps for survival, which could lead to severe community spread of the novel coronavirus. The COVID-19 pandemic has also affected the refugee population in the world, leading to further uncertainty vulnerability and risk for abuse from their places of refuge. They may not get access to health care during the times of crisis, leading to mental health issues in the already-troubled population.[63] Homeless, mentally ill persons are also having a high risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection due to higher vulnerability.[64]

People with comorbidities: The risk for already-sick people due to their medical comorbidities makes them very vulnerable to the novel coronavirus infection. This predisposes them to severe illness. Reports from China and Italy have shown that people who had medical comorbidities had increased severity of COVID-19, and mortality and morbidity was high among those people.[65,66] This leads to the perception of fear and anxiety among people with such conditions, thus affecting their ability to cope with the illness. Various protocols have been put in place for triaging the medical comorbidities with the COVID-19 disease; this can help clinicians to address their increased need for health care and effects on other bodily systems.[65] The mind and body relationship of the patient becomes very important while evaluating the comorbidities as both medical and psychological comorbidities affect the immune system in a significant way. The most commonly observed comorbidities along with COVID-19 were diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal diseases, cardiac diseases, systemic hypertension, and various malignancies. They pose great health risks for the sufferers and people with such illnesses. This leads to compromised immune status. When people with such conditions contact COVID-19, it leads to alteration in immune response and severe forms of the disease. The people with mental health comorbidity and preexisting anxiety and depression also have compromised immunity. Mental health affects the physical health of a person.[67] Thus, COVID-19, along with physical and psychological comorbidities, pose a significantly heightened risk for severe acute respiratory infection. Extra care is also required for people who are disabled. Due to disability, these people often require the assistance of others. As a result of which they are at higher risk of contracting the infection. To prevent the infection of disabled people, the Government of India has exempted them from the essential services, too, during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

STIGMA AND ATROCITIES ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19

Stigma is something that gets associated with all the people's belief systems and creates a certain attitude toward the phenomenon. Since the beginning of COVID-19, it was associated with devastation and death. This received a very negative global picture. There are a few reasons for all the negativity about COVID-19. The factors that attribute to higher stigma associated with COVID-19 are - highly contagious nature of the illness, tedious prevention measures, social distancing, non-availability of definite treatment options, prolonged quarantine, and the risk of serious complications and/or death. These features of the illness make it scary to be perceived by the general population;[68,69] an atmosphere of fear or a sense of impending doom is perceived among the health-care providers, patients, and general public; thus the issues of atrocities involving the family members of the affected persons, atrocities against the health professionals, and atrocities against racial or ethnic groups associated with the illness are present. The patients and family members have been reported to be discriminated against because of their serological status.[12,49,68] Health-care providers have been asked to vacate their houses to prevent infections in the communities. Chinese and Asian people have been mocked and bullied for being carriers of COVID-19 illness. Even in Indian states, people have been discriminated against and stigmatized due to their facial physical similarities to certain ethnic groups.[37,70] Due to the said stigma and the after-effects, people tend to hide their travel history, avoid testing, and resist government advisories, which are harmful to them and their communities, further propagating the pandemic. Doing more harm than good, stigma may lead to a downfall of the society as such.[12]

OPPORTUNITIES

Responses of the government: The COVID-19 pandemic is, by far, the most widespread and boundless human pandemic across the world, leading to the involvement of global organizations in the mitigation and management of the disease. The involvement of the world associations has brought about several changes in their functioning. The illness is extremely contagious and difficult to stop. It has infected many national and international leaders and has cost huge financial and economic burdens on nations. The reports from the United Nations and their Organizations and WTO have given extremely sad and unfortunate responses regarding the falling world economy and the threat of moving a huge number of the world population to poverty.[71] Various national governments have been reacting to the situation in various ways. The health-care system of the world is being tested globally. Medical, nursing, and paramedical workers are working to their capacities and often are facing a shortage of consumable items such as PPE and basic hygiene consumables such as hand wash and hand rubs. The nations throughout the world have virtually closed their borders and are not allowing movements across states as well. They have rolled out advisories and orders to maintain social distancing, and emergency and Militaries are being used to their fullest capacity to cope up with the pandemic situation. The international alliances are joining hands to help the developing nations and nations in crisis to cope and manage the pandemic situation[49]

Media response to COVID-19 and social distancing: The media tend to play a very important role in bringing people together in such difficult times. The media all over the world is taking the pandemic seriously with full coverage and rapid updates about the current situation. The Indian media has been especially supportive of the government in propagating correct measures of social distancing and encouraging the masses to maintain social-distancing protocols and creating online social engagement in support with the government.[8] Despite the efforts, the world's largest democracy, which had been facing issues, is now showing signs of adherence toward government advisories. In recent times, social media has been portraying an important role in the times of social distancing by encouraging and influencing the general population to stay home, giving in a sense that they are not alone in these dark times.[8,22] There had been efforts by the media to convey to the masses regarding the mental health issues. Some newspapers and radio channels are spreading the awareness through various talk shows, wherein they were able to interact and ask queries. The participation of Psychiatrists has been notable in helping the people out amid social distancing and quarantine of the people.[42]

Recommendations

Telepsychiatry: Currently, Telepsychiatry consultation gained popularity in view of lock-down, social distancing and fear of acquiring COVID-19 infection. The advancement of technology has brought about feasible access to health care through networking telephones and the Internet. These have widespread access to the majority public across states and nations; the current times are the best period to field test telepsychiatry measures as conventional visits pose a health risk to people and personnel. Various models of telepsychiatry can be put to use according to various national contexts. India has already started the use of mental health hotlines and helplines in place of the COVID-19 pandemic. The most common services during the COVID-19 pandemic can include the psychological first aid, identification of mental health issues, screening of psychological symptoms, and appropriate referrals. This can reduce the burden of work in the hospitals and will be an effective measure to reduce the footfall in the facilities, leading to maintenance of the social-distancing protocol. This may also help in making them feel that someone is always listening, and immediate help is available.[52] The Government of India has brought a telemedicine guideline for caring for the patients during this time, including the prescription of psychotropic medications using telemedicine services. This has been well received by the psychiatry community. For improving its practical utility, an official request was made to the Government of India by the Indian Psychiatric Society regarding the inclusion of certain otherwise prohibited psychotropic medication for telemedicine such as phenobarbitone, clobazam, and clonazepam for a prescription through telemedicine to which government readily agreed. This step is likely to be helpful for a wide variety of patients of psychiatric and neurological disorders

E-teaching: E-teaching is one of the best trends in vogue. The cost-effective internet prices and better technology have given rise to a great resource of healthcare-related knowledge. The E-teaching may be a great solution to complex problems during lockdowns and difficulties in taking physical classes; E-learning provides a platform for learning new materials.[43,55] Various schools in India and abroad have instituted E-class rooms. They are interactive and online methods that protect the children and teachers from contamination and help them get their lessons. This initiative in schools and medical professionals can also be prepared to target the interventions of COVID-19 and can upgrade their knowledge[43]

Resilience: Although everyone is suffering from the coronavirus pandemic and are unnerved and are trying to adapt, not everyone can cope effectively with stress and quickly adapts to new circumstances. Factors such as living conditions, deprivation, insufficient health-care access, possible future insecurity (i.e., career risk), genetic makeup, past experiences, social interactions,[72] and social assistance determine the resilience. Enhancing mental resilience will help combat the coronavirus[73] pandemic effectively.

Stress is a natural reaction to the pandemic. Potential stress-related responses to the coronavirus pandemic can involve inattention, irritability, anxiety, sleeplessness, reduced efficiency, and conflicts among members of the society. This may hold for the wider population, but especially to segments that are directly involved (e.g., health-care workers). It is necessary to emphasize that depression and anxiety are natural responses to a threatening situation.

In addition to the risk by the virus, there is certainly also a psychological distress effect of containment measures, thereby increasing the stress-related symptoms mentioned above. Somehow, the extent of these symptoms depends on the length and degree of quarantine, feelings of isolation, apprehension of infection, inadequate knowledge, and stigma.[74] For people with mental illness, stress from psychosocial dysfunction and health problems in the coronavirus pandemic will be a major concern. Global confusion, human health risks, and quarantine behavior can make symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, worse.

Furthermore, in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder and somatic symptoms and persons with a history of suicidal ideation, the risk of transmission may exacerbate the fear of contamination. While lockdown policies defend against coronavirus transmission, they encompass segregation and feeling of loneliness that cause extreme psychological distress and may cause or worsen mental illness.[75]

Under this context, the elderly should be given special consideration because they are more susceptible and separated from the rest of the population. The technological gap, i.e., the difference between generations that are aware of the currently emerging technologies and those who are not, might intensify the feelings of alienation and inadequacy among the older population. The inability to communicate on computers and mobile devices decreases social relationships. Besides that, normal accessibility to routine mental health services in most nations has also been greatly disrupted, and the compliance to pharmacological and psychological treatment modalities has been potentially decreased.

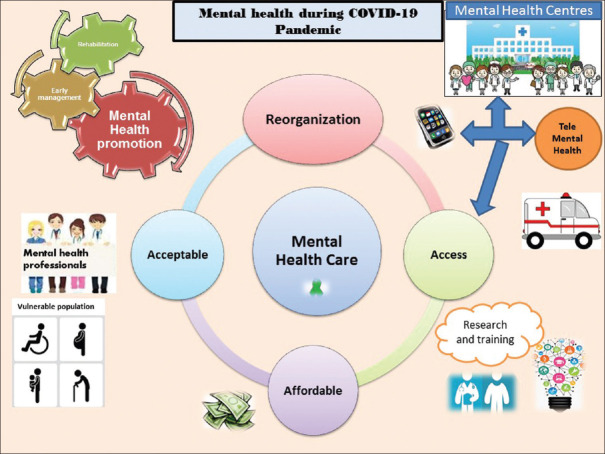

Other than the above recommendations, there is a need to improve the existing infrastructure, to avail essential medications, addressing the needs of the marginalized population, assessing the needs of health-care providers, removing stigma, and to keep a close watch on the aftermath of pandemic [Table 2]. The Figure 1 below depicts the mental health reorganization to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic by making it more acceptable, affordable, and accessible. Earlier, the only way for consultation was to attend conventional psychiatric clinics, which carried with it a stigma among the general population, especially in India. But now, with the beginning of telepsychiatry consultations, such stigma can be dealt with in a better way, and, also, other issues such as availability and affordability of consultation have improved. The aim is to improve the overall quality of mental health care by the inclusion of services such as telepsychiatry and placing emphasis on early detection and management and rehabilitation with special attention to the vulnerable population and improving research and training.

Table 2.

Summary of recommendations for COVID-19

| Summary of recommendations |

| Inclusion of psychiatrists in the task force to combat the COVID-19 pandemic in the country |

| Facilitating mental health research to understand the psychiatric aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Availability of psychotropic medications in hospital settings in adequate amount and ensuring uninterrupted supply of good-quality medicines |

| Addressing the mental health issues of the deprived sector of the society (migrated population, homeless people, slum people, refugees) |

| To keep strict vigilance on the aftermath of infection in the survivors of the corona pandemic |

Figure 1.

Reorganization of mental health to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li Z, Ge J, Yang M, Feng J, Qiao M, Jiang R, et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:916–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar SK, Sharma N, Verma SK, Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety and perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi W, Hall BJ. What can we do for people exposed to multiple traumatic events during the coronavirus pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102065. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102065. doi:101016/jajp2020102065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations [published correction appears in Gen. Psychiatr. 2020 Apr 27;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. e100213corr1. Gen Psychiatr 2020;33:e100213 Published 2020 Mar 6 doi:101136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 11] Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover S, Sahoo S, Mehra A, Avasthi A, Tripathi A, Subramanyan A, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 lockdown: An online survey from India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:354. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_427_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raony Í, de Figueiredo CS, Pandolfo P, Giestal-de-Araujo E, Oliveira-Silva Bomfim P, Savino W. Psycho-neuroendocrine-immune interactions in COVID-19: Potential impacts on mental health. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1170. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee D. The COVID-19 outbreak: Crucial role the psychiatrists can play. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;50:102014. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102014. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kar SK, Yasir Arafat SM, Kabir R, Sharma P, Saxena SK. Coping with Mental Health Challenges During COVID-19 Coronavirus Dis 2019. COVID-19. 2020:199–213. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horesh D, Kapel Lev-Ari R, Hasson-Ohayon I. Risk factors for psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: Loneliness, age, gender, and health status play an important role [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 13] Br J Health Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12455. 101111/bjhp12455 doi:101111/bjhp12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb L. COVID-19 lockdown: A perfect storm for older people's mental health [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 30] J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jpm.12644. 101111/jpm12644 doi:101111/jpm12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nursalam N, Sukartini T, Priyantini D, Mafula D, Efendi F. Risk factors for psychological impact and social stigma among people facing COVID-19: A systematic review. Syst Rev Pharm. 2020;11:1022–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pareek M, Bangash MN, Pareek N, Pan D, Sze S, Minhas JS, et al. Ethnicity and COVID-19: An urgent public health research priority. Lancet. 2020;395:1421–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coronavirus COVID-19 Disease. Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Society Register. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://presstoamuedupl/indexphp/sr/article/view/22506 .

- 18.Kavoor AR. COVID-19 in People with Mental Illness: Challenges and Vulnerabilities. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102051. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102051. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y, Bao Y, Lu L. Addressing mental health care for the bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:406–7. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, Kessler FHP, Ornell F, Schuch JB, et al. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42:232–5. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawohl W, Nordt C. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:389–90. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30141-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao Y, Torok ME. Taking the right measures to control COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:523–4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30152-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khosravi M. Perceived risk of COVID-19 pandemic: The role of public worry and trust. Electron J Gen Med. 2020;17:em203. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhav N, Oppenheim B, Gallivan M, Mulembakani P, Rubin E, Wolfe N. Pandemics: risks, impacts, and mitigation. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, et al., editors. Improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd ed. Vol. 9. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2018. Disease control priorities. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta R, Grover S, Basu A, Krishnan V, Tripathi A, Subramanyam A, et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:370. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee D, Rao TS. Sexuality, sexual well being, and intimacy during COVID-19 pandemic: An advocacy perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:418. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_484_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goyal K, Chauhan P, Chhikara K, Gupta P, Singh MP. Fear of COVID 2019: First suicidal case in India! Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;49:101989. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101989. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mamun MA, Griffiths MD. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren SY, Gao RD, Chen YL. Fear can be more harmful than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in controlling the corona virus disease 2019 epidemic. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:652–7. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Somani A. Dealing with corona virus anxiety and OCD. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102053. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kar SK, Arafat SMY, Sharma P, Dixit A, Marthoenis M, Kabir R. COVID-19 pandemic and addiction: Current problems and future concerns? Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102064. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102064. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zandifar A, Badrfam R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:101990. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixit A, Marthoenis M, Arafat SMY, Sharma P, Kar SK. Binge watching behavior during COVID 19 pandemic: A cross-sectional, cross-national online survey? Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113089. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113089. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhai Y, Du X. Mental health care for international Chinese students affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e22. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:23–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grover S, Mehra A, Sahoo S, Avasthi A, Tripathi A, D'Souza A, et al. State of mental health services in various training centers in India during the lockdown and COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:363. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_567_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kavoor AR, Chakravarthy K, John T. Remote consultations in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary experience in a regional Australian public acute mental health care setting? Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102074. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102074. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy D, Sinha K. Cognitive biases operating behind the rejection of government safety advisories during COVID19 Pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102048. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102048. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): The Impact and Role of Mass Media During the Pandemic Frontiers Research Topic. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://wwwfrontiersinorg/research-topics/13638/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-the-impact-and-role-of-mass-media-during-the-pandemic[Last accessed on]

- 41.Glenza J. US Medical Workers Self-Isolate Amid Fears of Bringing Coronavirus Home. The Guardian. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://wwwtheguardiancom/world/2020/mar/19/medical-workers-self-isolate-home-fears-coronavirus .

- 42.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saikia D. India's struggle with manpower shortages in the primary healthcare sector. Curr Sci. 2018;115:1033. [Google Scholar]

- 44.eLearning and COVID-19 Royal College of Psychiatrists. RC PSYCH R Coll Psychiatr. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://wwwrcpsychacuk/about-us/responding-to-covid-19/responding-to-covid-19-guidance-for-clinicians/elearning-covid-19-guidance-for-clinicians .

- 45.WHO Global Health Workforce Shortage to Reach 12. 9 Million in Coming Decades. WHO; [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alluri A. How India's Railways are Joining the Covid-19. Fight BBC News. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://wwwbbccom/news/world-asia-india-52212886 .

- 47.India Facing Shortage of 600,000 Doctors, 2 Million Nurses: Study-ET Health World. ETHealthworld.com. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. available from: https://health. economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/industry/india-facing-shortage-of-600000-doctors-2-million-nurses-study/68876861 .

- 48.Arabi YM, Murthy S, Webb S. COVID-19: A novel coronavirus and a novel challenge for critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:833–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05955-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohindra R, Ravika R, Suri V, Bhalla A, Singh SM. Issues relevant to mental health promotion in frontline health care providers managing quarantined/isolated COVID19 patients. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102084. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102084. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen ZL, Zhang Q, Lu Y, Guo ZM, Zhang X, Zhang WJ, et al. Distribution of the COVID-19 epidemic and correlation with population emigration from Wuhan, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(9):1044–1050. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000782. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, et al. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao S, Musa SS, Lin Q, Ran J, Yang G, Wang W, et al. Estimating the Unreported Number of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Cases in China in the First Half of January 2020: A Data-Driven Modelling Analysis of the Early Outbreak. J Clin Med. 2020;9:388. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020388. Published 2020 Feb 1. doi:10.3390/jcm9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Todd S, Diggle PJ, White PJ, Fearne A, Read JM. The spatiotemporal association of non-prescription retail sales with cases during the 2009 influenza pandemic in Great Britain. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004869. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004869. Published 2014 Apr 29. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caley P, Philp DJ, McCracken K. Quantifying social distancing arising from pandemic influenza. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5(23):631–639. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1197. doi:10.1098/rsif.2007.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhat R, Singh VK, Naik N, Kamath CR, Mulimani P, Kulkarni N. COVID 2019 outbreak: The disappointment in Indian teachers. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;50:102047. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102047. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh N, Gupta PK, Kar SK. Mental health impact of COVID-19 lockdown in children and adolescents: Emerging challenges for mental health professionals. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2020;16:194–8. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kar SK, Verma N, Saxena SK. Coronavirus infection among children and adolescents. In: Saxena SK, editor. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics. Singapore: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prevalence of Psychiatric Morbidity and Psychological Adaptation of the Nurses in a Structured SARS Caring Unit During Outbreak: A Prospective and Periodic Assessment Study in Taiwan – Science Direct. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 07]. Available from: https://wwwsciencedirectcom/science/article/pii/S0022395605001561 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Perceived Risk, Anxiety, and Behavioural Responses of the General Public During the Early Phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) Pandemic in the Netherlands: Results of three Consecutive Online Surveys Springer Link. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 07]. Available from: https://linkspringercom/article/101186/1471-2458-11-2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Luo Y, Yin K. Management of pregnant women infected with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:513–4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30191-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.RRH: Rural and Remote Health Article: 1179-Pandemic Influenza Containment and the Cultural and Social Context of Indigenous Communities. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 07]. Available from: https://wwwrrhorgau/journal/article/1179 . [PubMed]

- 62.Refugee and Migrant Health in the COVID-19 Response-The Lancet. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 07]. Available from: https://www thelancetcom/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736 (20) 30791-1/fulltextdgcid=hubspot_email_newsletter_tlcoronavirus20&utm_campaign=tlcoronavirus20&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=85659804&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-9AOxncNHTK1GIhH6-FENNTUYXO0qrXAeBcoOE7ZvvkScMmb748HVE9sSwVrNFvc5dWezuiXJT1×9F2uHeL7X29_VA5AgEHpxsTcWJKwTfmrA1jojQ&_hsmi=85659804 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Kar SK, Arafat SMY, Marthoenis M, Kabir R. Homeless mentally ill people and COVID-19 pandemic: The two-way sword for LMICs. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102067. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102067. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Comorbidities and Multi-Organ Injuries in the Treatment of COVID-19-The Lancet. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 07]. Available from: https://wwwthelancetcom/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736 (20) 30558-4/fulltext . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Lisi G, Campanelli M, Spoletini D, Carlini M. The possible impact of COVID-19 on colorectal surgery in Italy. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:641–2. doi: 10.1111/codi.15054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.D’Acquisto F. Affective immunology: Where emotions and the immune response converge. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19:9–19. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.1/fdacquisto. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Brakel WH, Cataldo J, Grover S, Kohrt BA, Nyblade L, Stockton M, et al. Out of the silos: Identifying cross-cutting features of health-related stigma to advance measurement and intervention. BMC Med. 2019;17:13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1245-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:228–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Onyeaka HK, Zahid S, Patel RS. The unaddressed behavioral health aspect during the coronavirus pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12:e7351. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7351. Published 2020 Mar 21 doi:107759/cureus7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.COVID-19 Pandemic Most Challenging Crisis Since Second World War: UN Chief; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://economictimesindiatimescom/news/international/world-news/covid-19-pandemic-most-challenging-crisis-since-second-world-war-un-chief/articleshow/74923642cms .

- 71.Speech-DDG Alan Wolff-DDG Wolff: COVID-19 Crisis Calls for Unprecedented Level of International Cooperation. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 08]. Available from: https://wwwwtoorg/english /news_e/news20_e/ddgaw_26mar20_ehtm .

- 72.The Science of Resilience: Implications for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression Science. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 07]. Available from: https://sciencesciencemagorg/content/338/6103/79abstract .

- 73.The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine. Available from: https://wwwnaturecom/articles/s41591-020-0820-9fbclid=IwAR1Nj6E-XsU_N6IrFN1m9gCT-Q7app0iO2eUpN5x7OSi-l_q6c1LBx8-N24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vahia IV, Blazer DG, Smith GS, Karp JF, Steffens DC, Forester BP, et al. COVID-19, mental health and aging: A need for new knowledge to bridge science and service. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:695–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]