Abstract

Introduction:

Given the paucity of research on how COVID-19 pandemic-associated lockdowns have affected the access to inpatient treatment, the present study was carried out.

Aims:

This study aims to describe (1) the characteristics of patients who accessed inpatient treatment, (2) the length of inpatient stay and readmissions, and (3) the quality and safety of care as indicated by the type of admission (voluntary/compulsory) and seclusion use during the lockdown period.

Materials and Methods:

For this comparative database study conducted at North West Area Mental Health Service, the study group included patients who had an admission between March 16, 2020 (starting of social distancing measures in Victoria) and May 12, 2020 (when easing [Stage 1] of social restrictions started). The control group included patients admitted between March 16, 2019, and May 12, 2019. The hospital databases were sources of information.

Results:

The study and control groups included 104 and 109 patients, respectively. Compared to the control group, the study group had significantly more patients with separated relationship status, a lower number of severe mental illnesses (SMIs), a higher number of substance use disorders, and lower readmissions. A subanalysis within the lockdown period showed more voluntary admissions in the initial phase whereas more compulsory admissions in the later phase at trend significance.

Conclusion:

Patients with a separated relationship status and a substance use disorder sought inpatient treatment more than others. Aside from exploring the reasons for these findings, it is also important to investigate why SMIs and readmissions decreased during the lockdown period through further studies.

Keywords: Access, COVID-19, inpatient, lockdown, pandemic

INTRODUCTION

The current coronavirus infection has affected the world tremendously. Governments have implemented lockdowns and strict social distancing measures to control the spread of the pandemic, and it is not without negative consequences on peoples' lives. The novel coronavirus named COVID-19 was first reported to the WHO from Wuhan, China, in December 2019. By January 30, 2020, it had spread to 21 countries with 9976 cases, when it was called a public health emergency of international concern. On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak, “a global pandemic” when cases had exceeded 100,000. Australia recorded its first case of COVID-19 on January 25, 2020. A total of 7461 cases have thus far been detected in Australia with 1836 identified in the state of Victoria with a total number of deaths at 102 on June 20, 2020[1] and continues to increase. To date, there are almost 9 million identified cases worldwide and 467,350 deaths related to the novel coronavirus.[2] To stop the spread of the coronavirus (“flatten the curve”), the Australian government introduced physical distancing rules and lockdowns. These rules were implemented on March 16, 2020 in the state of Victoria.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19, there has been a growing body of research around the psychological impact of COVID-19 infection, fear associated with infections in the general population, and quarantine itself. It is clear at this stage that quarantine has a negative impact on the mental health of individuals and most people can present with depression, stress, low mood, irritability, insomnia, posttraumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger as the predominant symptoms related.[3,4] A survey of the general public in Wuhan, China, during the early lockdown period suggested that more than half of the respondents rated the psychological impact of COVID-19 as moderate-to-severe, and about one-third reported moderate-to-severe anxiety.[5] Another study in India showed nearly three-fourths of the participants reporting moderate level of stress and low level of wellbeing and also a third reported anxiety.[4]

Studies examining the effects of quarantine in patients already experiencing mental illness revealed a much higher severity of concerns about their general health, anger, impulsivity, and strong suicidal ideation. Although the symptoms remained almost similar, the severity was significantly high.[6] Further, studies have noted differential effects of the pandemic and quarantine – patients with anxiety and mood disorders presenting with much higher perceived stress and somatic symptoms whereas it made little impact on patients having a schizophrenic illness.[7] A retrospective review from Germany revealed decreased utilization of psychiatric services by up to 26.6%. The study further revealed decreased utilization of inpatient services and in-hospital consultations during the periods of lockdown.[8]

Most reports on inpatient psychiatric treatment since the onset of the pandemic have been focused on the challenges associated with managing psychiatric patients in the acute inpatient settings due to lockdowns and around containment of infection if there is an eventual outbreak of infection within the unit.[9,10,11,12] To date, we found only one study reporting the rate of admission to an inpatient unit from the Lombard region of Italy, which noted a reduction of voluntary admission but a similar rate of compulsory admissions during the lockdown period. The authors attributed the decrease in voluntary admissions to fear of hospitals which are seen as possible sites of contagion, or families and clinicians not raising concerns regarding behavioral changes in patients.[13]

In the Australian context, mental health care is delivered by public services which are funded by state and private services that are subsidized by Medicare. However, inpatient services differ in that private inpatient services cater to only people voluntarily seeking help and are supported by private health insurance. Hence, patients who cannot afford private health insurance and all patients who need compulsory inpatient treatment receive treatment at public services. The care is provided in step-up and step-down pattern involving community teams and inpatient units and supported by prevention and recovery care (PARCs) for subacute presentations. It is fair to assume that the impact of the pandemic is still ongoing and may affect the clinical presentations reflected by changes to lockdowns and restrictions. We believe that an understanding of the profile of patients needing inpatient treatment during the pandemic will provide valuable information to develop policies and processes and help to tailor the focus of inpatient care. To date, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no study that has looked into characteristics of patients utilizing inpatient psychiatric care during the current pandemic in comparison to the previous years. We hypotheses that patients with severe mental illnesses (SMIs) would have sought the inpatient treatment less often whereas patients with poor coping with social stresses sought inpatient treatment more often during the lockdown period.

Aims

The aims were to examine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic-associated lockdown on:

The characteristics of patients accessing inpatient treatment

Any changes to bed-flow parameters such as length of stay (LOS) and readmissions, and

Quality and safety measures: legal status on admission (voluntary vs. compulsory admissions) and use of a key restrictive intervention, i.e., seclusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a comparative study with retrospective observational design. For this study, we included patients of North West Area Mental Health Service (NWAMHS), which is a part of Melbourne Health. NWAMHS is a state-funded public mental health service providing community-based and inpatient services to the residents of Hume and Moreland councils of Melbourne, Victoria. These two councils are located in the North West Region of Metropolitan Melbourne and cover about half a million people. The service runs a 25-bedded inpatient unit called Broadmeadows inpatient psychiatric unit (BIPU), two (Hume and Moreland) community clinics, prevention and care (PARC), and a community care unit. The service maintains a database derived from a state-wide database for admissions, discharges, community contacts, diagnosis, and legal status (voluntary vs. compulsory). The service also maintains a database derived from the state-wide service of Riskman which captures information about critical events including the use of seclusion.

BIPU provides inpatient services to patients aged 18–64 years and it receives referrals from the emergency department and community teams. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, patients needed to be screened through a questionnaire and if necessary, tested for COVID-19 before admission. If any patient developed COVID-19 symptoms, they would be isolated and monitored in a designated area within the intensive care area of the ward with support from the Victorian infectious disease service. Such patients are generally transferred to medical wards. Since the lockdown period, the hospital policy has been modified to stop visitors to the unit and to cancel day leaves. All staff needs to undergo a COVID-19 screen and temperature check when they enter the ward for their shifts. A key performance index (KPI) of the inpatient unit is 28-day readmission. In terms of service requirements, another KPI for the unit is to organize a minimum of two discharges per day. Patients are referred to the community services and their private provider for follow-ups. Following the lockdown measures, the community teams within the service have changed their model of care by reducing work hours, the use of telepsychiatry, reduced home visits and allowing some staff to work from home.

The Victorian government implemented the lockdown of nonessential services along with strict social distancing measures on the March 16, 2020. Following the “flattening of the curve” of the COVID-19 pandemic spread, the government started to ease the lockdown on the May 12, 2020. These two dates were used to define the study period. For comparison, the control period chosen was March 16, 2019–May 12, 2019.

Three sets of service delivery-related parameters were collected from the databases. These are (1) information about the nature of patients who accesses inpatient treatment: age, sex, marital status, and diagnosis, (2) admission flow: LOS and readmissions, and (3) quality and safety measures: the use of the Mental Health Act reflected as voluntary versus compulsory admissions and seclusion use as a marker of use of restrictive interventions. Data were extracted into Excel format.

The Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study as a quality assurance project. Data were de-identified and secured to meet privacy and confidentiality requirements. Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics (Chi-square test and independent t-test) with alpha (significance) level <0.05 were carried out through SPSS Ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Of the total of 213 patients, 109 were in the control period and 104 in the study period. On patient characteristics, groups were not different in age and gender but in relationship status that never married and married groups were more in the control period whereas the separated (including widowed and divorced) group was more in the study period (χ2= 9.38; P = 0.025) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison between control and study periods

| Variables | Groups | χ2/t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (2019) n (%)/mean±SD | Study (2020) n (%)/mean±SD | ||

| Age in years | 39.03±11.04 | 38.32±11.49 | NS |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 56 (51.4) | 56 (53.8) | NS |

| Female | 53 (48.6) | 48 (46.2) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 67 (61.5) | 55 (52.9) | χ2=9.379; |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 11 (10.1) | 27 (26.0) | P=0.025 |

| Married (includes de facto) | 22 (20.2) | 15 (14.4) | |

| Not stated | 9 (8.3) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Primary diagnosis – ICD10 | |||

| F10-19 | 5 (4.6) | 15 (14.4) | NS |

| F20-29 | 56 (51.4) | 41 (39.4) | |

| F30-39 | 24 (22.0) | 25 (24.0) | |

| F40-48 | 13 (11.9) | 8 (7.7) | |

| F50-59 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | |

| F60-69 | 10 (9.2) | 11 (10.6) | |

| Others | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Primary diagnosis - groups | |||

| Severe mental illness | 80 (73.4) | 66 (63.4) | χ2=6.25; |

| Nonsevere mental illness | 24 (22.0) | 23 (22.2) | P=0.04 |

| Substance use disorders | 5 (4.6) | 15 (14.4) | |

| LOS (in days) | 13.21±14.69 | 11.37±8.84 | NS |

| Readmission | |||

| No | 93 (85.3) | 95 (94.1) | χ2=4.268; |

| Yes | 16 (14.7) | 6 (5.9) | P=0.039 |

| Admission type | |||

| Voluntary | 74 (67.9) | 77 (74.0) | NS |

| Compulsory | 35 (32.1) | 27 (26.0) | |

| Seclusion | |||

| No | 106 (97.2) | 102 (98.1) | NS |

| Yes | 3 (2.8) | 2 (1.9) | |

ICD10 – International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; LOS – Length of stay; NS – Nonsignificant; SD – Standard deviation

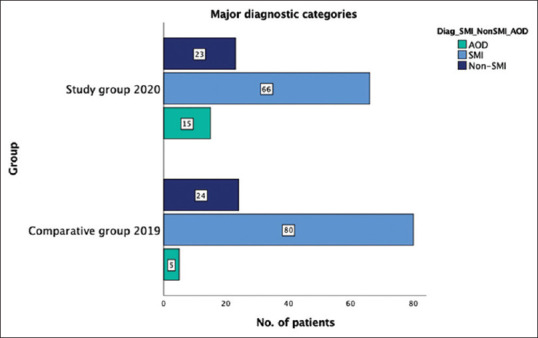

There was no group difference in broader International Classification of Diseases 10 diagnostic categories. However, when diagnoses were grouped into three major groups such as SMIs (F20–29 and F30–39), non-SMIs (all except F10–19, F20–29 and F30–39), and substance use disorder (F10–19), there was a significant group difference (P = 0.044) that in the study period, SMIs were about 10% less whereas substance use disorders were up by 10% [Figure 1]. There was no group difference in the LOS but readmissions were significantly less in the study period (χ2= 4.268, P = 0.039). On service quality and safety parameters, there was no group difference in seclusion rate [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Group comparison on major diagnostic groups. AOD – Alcohol and drug; SMI – Severe mental illnesses; Non-SMI – Nonsevere mental illnesses

A subsequent analysis was done by dividing the study period into two equal periods of 29 days, i.e., the first (i.e., March 16, 2020–April 13, 2020) and the second (i.e., April 14, 2020–May 12, 2020) period of strict social measures. Groups did not differ in all the study variables except a trend significance of the higher rate of voluntary admissions in the first period (81.5% vs. 66%) whereas compulsory admissions were more in the second part (18.5% vs. 34%) (χ2= 3.237, P = 0.07) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison between first and second parts of the lockdown period

| Variables | Lockdown period | χ2/t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First part n (%)/mean±SD | Second part n (%)/mean±SD | ||

| Age in years | 38.87±11.39 | 37.72±11.68 | NS |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 29 (53.7) | 27 (54.0) | NS |

| Female | 25 (46.3) | 23 (46.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 27 (50.0) | 28 (56.0) | NS |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 14 (25.9) | 13 (26.0) | |

| Married (includes de facto) | 10 (18.5) | 5 (10.0) | |

| Not stated | 3 (5.6) | 4 (8.0) | |

| Primary diagnosis – ICD10 | |||

| F10-19 | 8 (14.8) | 7 (14.0) | NS |

| F20-29 | 20 (37.0) | 21 (42.0) | |

| F30-39 | 14 (25.9) | 11 (22.0) | |

| F40-48 | 4 (7.4) | 4 (8.0) | |

| F50-59 | 1 (1.9) | 0 | |

| F60-69 | 7 (13.0) | 4 (8.0) | |

| Others | 0 | 3 (6.0) | |

| Primary diagnosis - groups | |||

| Severe mental illness | 34 (63.0) | 32 (64.0) | NS |

| Nonsevere mental illness | 12 (22.2) | 11 (22.0) | |

| Substance use disorders | 8 (14.8) | 7 (14.0) | |

| LOS (in days) | 11.74±9.99 | 10.87±7.37 | NS |

| Readmission | |||

| No | 49 (90.7) | 46 (97.9) | NS |

| Yes | 5 (9.3) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Admission type | |||

| Voluntary | 44 (81.5) | 33 (66.0) | χ2=3.24; |

| Compulsory | 10 (18.5) | 17 (34.0) | P=0.07 |

| Seclusion | |||

| No | 53 (98.1) | 49 (98.0) | NS |

| Yes | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.0) | |

ICD10 – International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; LOS – Length of stay; NS – Nonsignificant; SD – Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

Both the study and control groups had a nearly comparable total number of admissions. This is in contrast to a German study that showed a decline in the use of psychiatric services including inpatient admissions during the lockdown period.[8] The potential reasons for our finding could be the hospital KPI that directs two discharges per day, a lower bed to population ratio in Victoria and thus there is a constant demand for inpatient beds, and a low threshold for admission because of the reduced functioning of the community mental health teams during the lockdown.

The main finding of our study was a near 10% drop in admissions associated with SMIs that paralleled about a 10% increase in admissions for substance use disorders. We do not know the exact reason for this finding, but we suspect that patients with SMIs did not feel the effect of lockdown as they commonly experience social isolation even before the lockdown[14] and they might have fallen in the gaps because of reduced functioning of community teams due to lockdown measures.

In general, patients who accessed the inpatient treatment during the lockdown and the control periods were comparable in their age and gender. However, our study found patients with separated (including divorced and widowers) relationship status more than those who are single or in a stable relationship in the study period. On one hand, separated relationship status could suggest that this group of patients would have felt the effect of lockdown mode because of double stress (i.e., lockdown and loss of relationship) and thus sought admission. Besides, those who were separated from their partners could have experienced additional psychosocial stresses such as financial hardships and loss of viable accommodation during the lockdown which could have further affected their mental health.

Another key finding was the decrease in readmissions. It is a favorable finding as readmissions are a marker of quality and efficiency of healthcare services.[15] However, a spontaneous decrease in readmissions by over 50% can result from patients' avoiding subsequent admissions because of fear of catching an infection in the ward as reported elsewhere.[8] Further, it is also possible that the lack of visits from family and friends and lack of day leaves might have acted as a deterrent for further hospital admissions, particularly for voluntary patients. In our study, there was no significant group difference in the LOS and seclusion episodes. These findings were within the KPIs[16] and it suggests that there was no change in the quality of care received.

A previous study at Lombardy in Italy reported a reduction in voluntary admissions because of fear of hospital-acquired infection.[13] While there was no significant difference in voluntary versus compulsory admissions between the study and control groups, our study found a potentially significant increase in the voluntary admissions during the early phase of the lockdown. It is possible that the lower number of COVID-19 cases in Australia might have reassured the population that the hospitals are safe and thus enabled individuals who experienced psychological stress and associated mental health conditions to seek hospital care during the early period of the lockdown. There were no other significant differences between the early and later part of lockdown periods.

There are limitations to our study. These include retrospective study design, availability of a limited number of sociodemographic and clinical variables only, and not measuring patients' perception of the quality of care and psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 period. Nonetheless, our study is unique in exploring the effect of the current pandemic on acute access and thus our findings will add to the literature on this topic.

CONCLUSION

Our study has shown that individuals with SMIs are less likely to receive inpatient care during the pandemic whereas individuals with substance use disorders are more likely to use inpatient admission. The reasons for individuals with SMIs seeking inpatient care comparatively less frequently need exploration, for example, access issues, psychopathology affecting them feel more paranoid to be in the hospital during the pandemic, and systemic factors. A further study with a prospective design, larger sample size, and assessing patients' experiences through a standardized instrument will help to confirm our findings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Bing Xue Toh for supporting with data extraction from the databases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers. Department of Health, Australian Government. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 28]. Available from: https://wwwhealthgovau/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers .

- 2.World Health Organisation Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 28]. Available from: https://covid19whoint .

- 3.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover S, Mehra A, Avasthi A, Tripathi A, Subramanyan A, Pattojoshi A, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 lockdown: An online survey from India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:354–62. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_427_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020:17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hölzle P, Aly L, Frank W, Förstl H, Frank A. COVID-19 distresses the depressed while schizophrenic patients are unimpressed: A study on psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113175. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoyer C, Ebert A, Szabo K, Platten M, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kranaster L. Decreased utilization of mental health emergency service during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01151-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, Gearin P, Olcott W, Shankar V, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113069. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang YT, Zhao YJ, Liu ZH, Li XH, Zhao N, Cheung T, et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: Managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1741–4. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skelton L, Pugh R, Harries B, Blake L, Butler M, Sethi F. The COVID-19 pandemic from an acute psychiatric perspective: A London psychiatric intensive care unit experience. BJPsych Bull. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2020.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Zhang Y. Mental healthcare for psychiatric inpatients during the COVID-19 epidemic. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100216. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clerici M, Durbano F, Spinogatti F, Vita A, de Girolamo G, Micciolo R. Psychiatric hospitalization rates in Italy before and during COVID-19: did they change? An analysis of register data. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eglit GML, Palmer BW, Martin AS, Tu X, Jeste DV. Loneliness in schizophrenia: Construct clarification, measurement, and clinical relevance. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian commission on safety and quality in health care. Avoidable hospital readmissions: Report on Australian and international indicators, their use, and the efficacy of interventions to reduce readmissions. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Information VAfH. Adult Mental Health Performance Indicator Report 2019-20-Quarter 1 Healthvicgovau. 2020:9. [Google Scholar]