Abstract

Background:

The health-care workers showed the highest risks of the adverse psychological reactions from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aim:

This study aimed to evaluate the structure and severity of psychological distress and stigmatization in different categories of health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods:

This study included two phases of online survey in 1800 Russian-speaking health-care workers (March 30 – April 5 and May 4 – May 10, 2020). The Psychological Stress Scale (PSM-25) and modified Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination scale (Cronbach's α = 0.74) were used. Dispersion analysis was performed with P = 0.05, Cohen's d, and Cramer's V calculated (effect size [ES]).

Results:

The psychological stress levels decreased in the second phase (ES = 0.13), while the stigma levels (ES = 0.33) increased. Physicians experienced more stress compared with nurses and paramedical personnel (ES = 0.34; 0.64), but were less likely to stigmatize SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals (ES = 0.43; 0.41). The increasing probability of contact with infected individuals was associated with higher levels of psychological stress (probable contact ES = 0.48; definite contact ES=0.97). The highest rates of contacts with COVID-19 patients were reported by physicians (χ2 = 123.0; P = 0.00, Cramer's V = 0.2), the youngest (ES = 0.5), and less experienced medical workers (ES = 0.33).

Conclusion:

Direct contact with coronavirus infection is associated with a significant increase in stress among medical personnel. The pandemic compromises the psychological well-being of the youngest and highly qualified specialists. However, the stigmatizing reactions are not directly associated with the risks of infection and are most prevalent among nurses and paramedical personnel.

Keywords: Anxiety, COVID-19, distress, health-care workers, stigma

INTRODUCTION

During the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection, health-care systems have faced a critical overload of their resources.[1] Other problems include the high risks for medical personnel's lives and constant feelings of real threat.[2] Previous outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS, 2003) caused a number of adverse psychological reactions among health-care workers.[3,4,5,6] The COVID-19 pandemic can also lead to an increase in stigma because it is a novel unknown infection.[7] Medical workers' stigmatizing attitudes toward patients could be the major obstacle to communication and adequate assistance.[8,9,10]

The aim of our study is to evaluate the structure and severity of psychological distress and stigmatization in different categories of health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research design

The data were obtained from the two phases of the online survey. The participants were proposed to complete a self-reported questionnaire via the Google Forms online platform, which on an average took about 15 min [the complete version is available in Appendix 1]. The questionnaire included sociodemographic characteristics and the history of chronic illnesses. A special form for health-care workers also included questions on the medical experience and specialization. The questionnaire was distributed through social media and via websites of public organizations and thematic communities (see acknowledgments).

Inclusion criteria were: age ≥18; ability to read and understand text in Russian; and consent to personal data processing. Noninclusion criterion was: Incomplete data in any section of the questionnaire. The study was performed in accordance with the WMA Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net/e/policy/17-c_e.html). The study was approved by the local institutional review board at V. M. Bekhterev National Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Neurology. All participants gave their consent to the processing of personal data before enrollment.

To verify the level of anxiety distress, the respondents completed a Psychological Stress Scale (PSM-25) (translated and adapted for the Russian-speaking population version).[11] An integral score of psychological stress is the total score, which allows to indicate three levels (high – the sum ≥155 points indicates maladaptation and the need for psychological correction; average –154–100 points; low – 100 points indicates psychological adaptation to stresses).

The statements describing the negative perception of individuals with the symptoms of respiratory infection (coughing, coryza, and sneezing) were based on the Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination section [PDD]).[12] The levels of agreement with the questionnaire statements were evaluated with the use of a 4-point Likert scale. The higher total scores corresponded to more severe stigma intensity (a maximum of 36 points and a minimum of 9 points).

Furthermore, the respondents could describe how often they requested information about a pandemic during the last week in the range from “never” to “every hour” (according to a 8-point scale).

The second phase of the survey included additional questions on whether the respondent had any contacts with people infected with SARS-CoV-2 and whether the respondent had been infected him-/herself.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data processing was carried out using the SPSS-16 software package (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL; USA). The descriptive statistics were used. Distribution normality test was performed using the skewness and kurtosis calculation. Dispersion analysis for data with nominal scales was performed using Pearson's Chi-square criterion, the data for ordinal scales were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis H-test and Mann–Whitney U-criterion, and the data for interval scales were analyzed using ANOVA. For the purpose of data presentation with uniformity, the results were given with the indication of average mean ± standard deviation, as well as median and interquartile range for nominal scales. Effect sizes obtained using Cohen's d and Cramer's V measures were calculated for groups, the differences between which had the significance level of P ≤ 0.05. Estimation of the effect size was made according to the following generally accepted criteria: weak (0.10–0.29), moderate (0.3–0.49), and strong (≥0.50). When comparing the nominal attributes with more than two gradations, the interpretation of the effect size was corrected for the number of degrees of freedom and the threshold values for a weak/medium/strong effect.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the studied sample

The final sample included 1800 records of health-care workers. A total of 223 were completed during the 1st week of recommended self-isolation in Russia (from March 30 to April 5), others in May 2020.

A total of 1434 residents from all Russian federal districts participated in the survey (45% of the sample during the first phase and 68% during the second phase). In addition, there was a significant number of respondents from federal cities (Moscow – 97 people [21% and 6% of the sample during the first and second phases, respectively] and St. Petersburg – 269 people [34% and 21%, respectively]). A total of 1459 women (79.5% of the first phase cohort and 89.5% of the second phase cohort) and 341 men were evaluated. The regional and gender variability of the sample differed significantly between the two study phases. The average age was 42 ± 12 years and the average work experience was 17 ± 12 years. During the second phase of the survey, 50% of the participants reported definite lack of contact with COVID-19 patients, 39% were unsure about it, and 11% reported definite contact. Physicians (84% of the subgroup, 16.5% of nurses and 1.5% of paramedical personnel, χ2 = 123.0, P = 0.00, Cramer's V = 0.2; considering the degrees of freedom n = 4, the size of the effect is average), youngest specialists (average age 36 ± 12 years; Cohen's d = 0.5), and least experienced health-care workers (13 ± 12 years; Cohen's d = 0.33) prevailed among those who had contacted coronavirus-infected patients. Moreover, 22 respondents (1.4%) reported that they themselves had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The history of chronic somatic diseases was reported by 743 participants (41%). More detailed sociodemographic data of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Number of respondents (percentage of the sample in stages 1 and 2) |

|---|---|

| Marital status | |

| Widowed | 67* (1.5/4) |

| Divorced | 211* (9.5/12) |

| Single | 347* (29.5/18) |

| Constant partner | 154* (13/8) |

| Officially married | 1021* (46.5/58) |

| Education | |

| Incomplete primary | 6* (0/0.5) |

| Primary | 29* (0/2) |

| Secondary | 588* (2/37) |

| Incomplete higher | 76* (6.5/4) |

| University degree | 980* (73/51.5) |

| Scientific degree | 121* (18.5/5) |

| Employment | |

| Unemployment | 11* (2/0.5) |

| Students/residents | 90* (11.5/4) |

| Business owners | 7* (2.5/0.5) |

| Personnel of private organizations | 75* (9/3.5) |

| Personnel of public organizations | 1617* (75/91.5) |

| Specialty | |

| Psychiatry | 524* (57/25) |

| Anesthesiology/ICU | 30* (0.5/2) |

| Epidemiology, infection diseases | 22* (1.5/1) |

| Internal medicine, pulmonology, general practice | 72* (5/4) |

| Other medical specialties | 485* (33.5/26) |

| Nurses | 604* (2/38) |

| Paramedical stuff | 63* (0.5/4) |

*In case of significant differences of percentages in Stages 1 and 2 (P<0.05). ICU – Intensive care unit

Characteristics of psychological and behavioral reactions of the respondents to the pandemic

The average level of psychological stress for the whole sample did not reach the threshold values of moderate intensity (77.1 ± 30.9 points according to the PSM-25 scale). Physicians experienced more intense stress (81.2 ± 31.0), compared to nurses (70.7 ± 30.0; Cohen's d = −0.34) and paramedical personnel (62.8 ± 26.1; Cohen's d = −0.64). Anesthesiologists and intensive care units (ICU) specialists were the most exposed to distress (103.0 ± 22.4 points; Cohen's d = 0.81). Their average stress level was higher compared even to that of coronavirus-infected respondents (96.5 ± 28.6; uninfected individuals – 72.3 ± 30.9; Cohen's d = 0.68). The increasing probability of the contact with infected individuals was associated with the higher levels of psychological stress (definitely no contact – 67.9 ± 29.0, probable contact – 81.8 ± 29.3, Cohen's d = 0.48; definite contact – 97.5 ± 31.0, Cohen's d = 0.97). An additional factor associated with greater psychological stress was the lack of a constant partner (87.4 ± 31.5), compared to widowed (67.7 ± 32.8; Cohen's d = 0.61), divorced (75.0 ± 29.7; Cohen's d = 0.41), and officially married respondents (74.0 ± 29.5; Cohen's d = 0.44).

Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (PDD), modified for this study, demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency of Cronbach's α = 0.74. In accordance with its total score, the level of stigmatization of individuals with respiratory symptoms also corresponded to medium values (17.5 ± 3.4 points). Physicians were less likely to stigmatize patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (16.9 ± 3.3 points) than nurses (18.3 ± 3.2 points; Cohen's d = 0.43) and paramedics (18.3 ± 3.5 points; Cohen's d = 0.41).

On an average, health-care workers searched the media for news about the pandemic once a day (median = 5, Q25 = 5, Q50 = 6), simultaneously used four of the six coronavirus preventive measures (median = 4; Q25 = 3, Q50 = 5), and reported three coronavirus-related concerns (median = 3, Q25 = 2, Q50 = 5). Overall, the reports of contact with SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals were associated with fewer practical protective measures (median = 4; Q25 = 3, Q50 = 5) and a greater number of pandemic concerns (median = 4; Q25 = 3, Q50 = 5), compared to the absence of coronavirus contact: number of protective measures (median = 5, Q25 = 4, Q50 = 5) and number of COVID-19 concerns (median = 3, Q25 = 2, Q50 = 5 (P < 0.05). Physicians on an average practiced significantly fewer strategies for infection prevention (median = 4; Q25 = 3, Q50 = 5), compared to nurses (median = 4; Q25 = 5, Q50 = 5).

Analysis of practiced infection prevention strategies in medical workers showed no dynamics between the first and second stages of the survey (washing hands – 94% and 95% of the sample; physical distancing – 73% and 74%) or a significant increase of usage (wearing masks – 64% and 89%; wearing gloves – 30% and 57%; and usage of sanitizer – 64% and 82%). Only self-isolation showed a decrease in usage frequency – 49% and 36%, respectively (χ2 = 16.0, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.1).

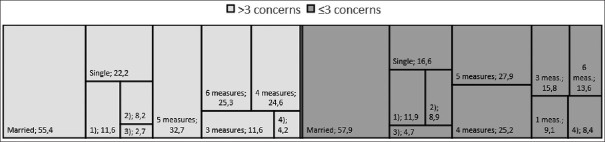

Factors associated with an increase in the number of pandemic's concerns

The sample was divided into two sub-cohorts according to the low and high numbers of concerns. Respondents with high number of concerns (on an average median = 5) exceeding the median value of the whole sample had significantly higher levels of psychological stress (82.7 ± 30.7 and 71.2 ± 30.1 scores, respectively; Cohen's d = 0.36). They also demonstrated slightly less increase of devaluation/discrimination index level (17.7 ± 3.4 and 17.2 ± 3.4 scores, respectively; Cohen's d = 0.15). This group had all types of pandemic-associated anxiety more often. Health-care workers in this subcohort practiced all the strategies of infection prevention more frequently and [Figure 1] used a high number of them simultaneously (χ2 = 99.2, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.24; n = 5, strong effect size). Those who are single or unmarried (χ2 = 12.7, P = 0.01, Cramer's V = 0.08; n = 4, weak effect size), young (39 ± 12 and 42 ± 12 years, respectively; Cohen's d = 0.24), and medical professionals with less working experience (15 ± 12 and 18 ± 12 years accordingly; Cohen's d = 0.21) tend to have different anxiety concerns more frequently.

Figure 1.

Marital status and number of practiced protection strategies in respondents according to their pandemic's concerns, % (χ2 = 99.2, P ≤ 0.05). (1) Divorced, (2) constant partner, (3) widowed, (4) 2 strategies

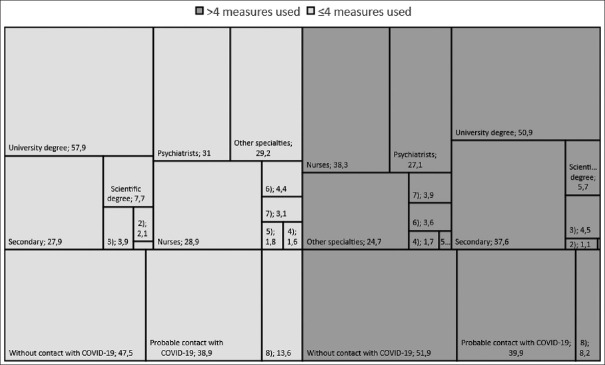

Factors associated with a high number of strategies for coronavirus infection prevention

The study participants, who practiced high number of COVID-19 preventive strategies (median = 5) compared to median value in the whole sample, stigmatized individuals with respiratory symptoms more frequently (17.9 ± 3.4 and 17.0 ± 3.3 points, respectively; Cohen's d = 0.27). They used all the infection protective strategies more often. At the same time [Figure 2], they were less confident in their contact with COVID-19 patients (χ2 = 12.1, P = 0.002, Cramer's V = 0.09; n = 2, weak effect size). The most common concern themes associated with COVID-19 in this group were: “virus contagiousness” (42.0% in participants practiced high number of preventive strategies and 25.2% in participants practiced low number of preventive strategies; χ2 = 59.9, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.18), “absence of specific treatment” (49.9% and 37.3%; χ2 = 29.1, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.13), “fear for own life” (49.1% and 29.8%; χ2 = 70.0, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.2), “threat to the lives and health of relatives and close people” (86.1% and 75.5%; χ2 = 32.6, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.13), and “lack of protection equipment for sale” (26.7% and 18.2%; χ2 = 18.7, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.1). Respondents who tend to use a high number of protection strategies had lower levels of education and more likely had secondary medical education (χ2 = 25.1, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.12; n = 5, weak effect size). Nurses were most prevalent in this subcohort (χ2 = 23.4, P = 0.001, Cramer's V = 0.11; n = 6, medium effect size). The respondents of this subcohort also were older (42 ± 12 and 40 ± 12 years, respectively The respondents of this subcohort also were older (42 ± 12 for participants practiced high number of preventive strategies and 40 ± 12 years for participants practiced low number of preventive strategies; P = 0.002; Cohen's d = 0.14) and had longer working experience (18 ± 13 and 17 ± 12 years, respectively; P = 0.00; Cohen's d = 0.19).

Figure 2.

Education, specialties, and probability of the contact with COVID-19 in respondents according to their number of practiced protective strategies % (χ2 = 25.1; 23.4; 12.1, P ≤ 0.05). *<1%, **<2%, (1) incomplete primary education, (2) primary education, (3) incomplete higher, (4) anesthesiology/ICU, (5) epidemiology/infectious diseases, (6) internal medicine/pulmonology/general practitioners, (7) paramedical stuff, (8) contact with COVID-19. ICU – Intensive care unit

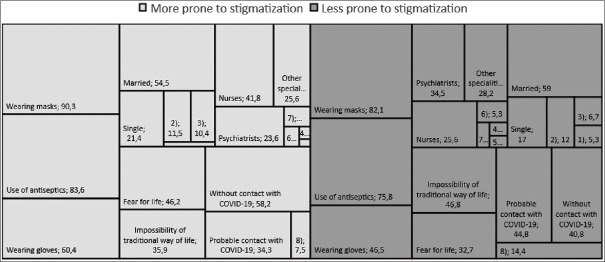

Factors associated with stigmatization of COVID-19 patients

The subcohort of respondents who were more willing to share discriminatory attitudes toward patients with coronavirus (average stigmatization rates were higher than median) had lower level of psychological stress (74.8 ± 31.6 in respondents willing to share discriminatory attitudes and 79.3 ± 30.1 scores in respondents who less willing to share discriminatory attitudes; Cohen's d = 0.15). Discrimination/devaluation of individuals with respiratory symptoms was typical for the vast majority of medical workers [Figure 3] who had no personal contact with this category of patients (χ2 = 52.7, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.18; n = 2, weak effect size). “Fear for own life” was more common concern theme for this subcohort than in overall sample (χ2 = 34.1, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.14), and “impossibility of traditional way of life” was the least common for these respondents (χ2 = 22.2, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.11). Health-care workers who tend to stigmatize patients with COVID-19 did not use several strategies for infection prevention simultaneously. On the contrary [Figure 3], they tend to use individual particular protection strategies more often (wearing masks [χ2 = 25.5, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.12], gloves [χ2 = 34.8, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.14], and using antiseptics [χ2 = 17.0, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.1]). In this subcohort, women (85.6% vs. 76.7% among nonstigmatizing respondents; χ2 = 23.0, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.11) and older health-care workers (43 ± 12 and 40 ± 12 years, respectively; P = 0.00; Cohen's d = 0.24), those with longer working experience (18 ± 12 and 16 ± 12 years, respectively; P = 0.00; Cohen's d = 0.21), nurses (χ2 = 71.9, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.2; n = 6, strong size effect), and widows and persons who live in de facto marriage (χ2 = 25.3, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.12; n = 4, weak effect size) were more prevalent.

Figure 3.

Marital status, specialties, probability of the contact with COVID-19, concerns about pandemic, and certain protective stages in respondents according to their tendency of stigmatization, % (χ2 = 25.3; 71.9; 52.7; 22.2–34.1; 17–34.8, P ≤ 0.05). *≤1,5%, **≤2,5%, (1) widowed, (2) divorced, (3) constant partner, (4) anesthesiology/ICU, (5) epidemiology/infectious diseases, (6) internal medicine/pulmonology/general practitioners, (7) paramedical stuff, (8) contact with COVID-19. ICU – Intensive care unit

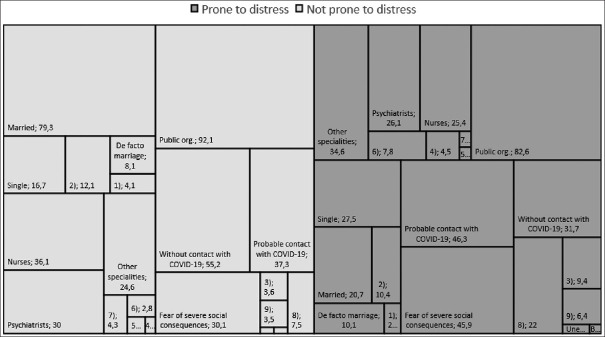

Distress type factors of medical health workers' response to the pandemic

Considering the exceptional practical importance, we separately analyzed a subcohort of health-care professionals who demonstrated a level of psychological stress that exceeded the threshold values (in total 23.6% – 425 respondents). These respondents demonstrated a relative decrease in the stigmatization level of individuals with respiratory symptoms (17.2 ± 3.4 and 17.5 ± 3.4 scores, respectively; Cohen's d = 0.09), despite the fact that these participants more often reported about direct contact with COVID-19 patients [Figure 4] or suspected such a contact (χ2 = 91.2, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.24; n = 2, medium effect size). There were also slightly more cases of medical workers infected with SARS-CoV-2 themselves (3.0% vs. 0.9% among those who had less level of stress; χ2 = 9.2, P = 0.002, Cramer's V = 0.08). The increase of psychological distress in respondents was associated with an increase (P < 0.05) in the number of simultaneously present concerns about coronavirus (median = 4; Q25 = 3, Q50 = 5). The most prevalent anxiety concern theme was “severe social consequences” (χ2 = 36.1, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.14).

Figure 4.

Marital status, specialties, employment, probability of the contact with COVID-19, and concerns about pandemic according to their distress, % (χ2 = 29.8; 82.4; 34.3; 91.2; 36.1, P ≤ 0.05). *<1%, **<1,5%, (1) widowed, (2) divorced, (3) students/residents, (4) anesthesiology/ICU, (5) epidemiology/infectious diseases, (6) internal medicine/pulmonology/general practitioners, (7) paramedical stuff, (8) contact with COVID-19, (9) unemployment, (10) private organizations. ICU – Intensive care unit

Health-care workers exposed to anxiety distress were more likely to have concomitant somatic disease (53.4% vs. 37.5% among persons with less level of stress; χ2 = 33.8, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.14). Individuals who had no family relationships or lived in de facto marriage were most prevalent in this subcohort (χ2 = 29.8, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.13; n = 4, weak effect size). Most of the distress-prone respondents were physicians of different specialties, especially anesthesiologists/ICU specialists and internal medicine specialists/pulmonologists (χ2 = 82.4, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.21; n = 6, strong effect size). In addition, this subcohort included the youngest respondents (37 ± 12 in distress-prone respondents and 42 ± 12 years in less distress-prone respondents; P = 0.00; Cohen's d = 0.50) with shorter working experience (13 ± 12 and 18 ± 12 years, respectively; P = 0.00; Cohen's d = 0.39). Respondents from a distress-prone subcohort more often worked in private health organizations or were getting an education than their more stress resistant colleagues (χ2 = 34.3, P = 0.000, Cramer's V = 0.14; n = 4, weak effect size).

Dynamics of health-care workers' response to the pandemic

The characteristics of health-care professionals' reactions in response to COVID-19 spread were not static. The cohort evaluated in the second phase of the study was characterized by a decrease in the average level of psychological stress (from 80.6 ± 31.0 to 76.6 ± 31.0; Cohen's d = 0.13). However, the respondents' score of the devaluation/discrimination scale increased from the first to the second phases (16.5 ± 3.3 vs. 17.6 ± 3.4; Cohen's d = 0.33). Respondents of the second phase practiced a higher number of strategies for infection prevention simultaneously (median = 4, Q25 = 3, Q50 = 5 vs. median = 5, Q25 = 4, Q50 = 5; Cramer's V = 0.16; n = 5, medium effect size). They also reported a decrease in the frequency of accessing news about the pandemic in the media (median = 6, Q25 = 5, Q50 = 6 vs. median = 5, Q25 = 5, Q50 = 6; Cramer's V = 0.21; n = 7, strong effect size).

DISCUSSION

Our study analyzed the miscellaneous parameters of health-care workers' psychological response to the pandemic. They included an integral score of psychological stress, reflecting the severity of emotional, cognitive, and somatized reactions; social and behavioral defense responses; and phenomenological aspects of anxiety. For the first time, data were obtained on the rates of stigmatization of patients with COVID-19 among Russian health-care professionals. The results of the study demonstrate that the adaptation of medical workers to the coronavirus infection spread is procedural in nature and their reactions to a pandemic change at different stages of the epidemic process.

During the 1st week of the anti-epidemic nonworking regime in Russia, the primary response to the novel coronavirus infection spread in the studied sample was associated with an active search for information about COVID-19 (average – daily). Stress response was normal and was not associated with an increase in the integral score of psychological stress according to PSM-25 (77.1 ± 30.9 points), which was lower than the threshold of average stress level. This score was also lower compared to the general Russian population scores during the 1st week of quarantine.[13] The adaptive type of response to a pandemic, in the form of a stress level reduction after 1 month, was probably associated with an increase in awareness of a new infection. This trend is characteristic not only for medical workers in Russia, but also for India[14] and China.[15,16] In the second stage of our study, this was confirmed by a decrease in the frequency of media requests by respondents. It is important that with a decrease in the levels of psychological stress, the scores of devaluation/discrimination increased among medical workers over time.

Despite the initially low and further decreased time level of stress in the cohort, stress scores were heterogeneous among different groups of specialists. The most vulnerable were internists, pulmonologists, anesthesiologists, and ICU specialists, who had the greatest risks of contact with SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, which is consistent with previously published materials.[17,18]

Like many literature sources, our data demonstrated that the most unfavorable distress type of response to a pandemic was characteristic for sub-cohorts of young specialists,[19,20,21] those with less medical experience,[22] primarily physicians,[22] those without social support in family relationships,[23,24] and those with a high risk of contact with COVID-19 patients.[21,25,26,27,28] Another important and expected[22,27,29,30] factor of anxious maladaptation was the history of chronic somatic illness.

At the same time, the part of Russian respondents vulnerable to distress (23.6%) in our study turned out to be lower compared with health-care workers in India (33%)[22] and China (mainly Hubei Province, 72%).[25] However, it was significantly higher than the prevalence of distress among medical specialists in a multinational study (9%),[30] as well as in the general adult population of the USA (14%).[31] The risks of an unfavorable response for health-care workers were associated with the mechanism of anxious distress. There was an increase in the number of types of concerns about COVID-19 and the predominance of a humanistic plot of excitement about the social consequences of the pandemic. The latter is probably generally characteristic of health-care professionals.[14,22]

The respondents' adaptive-compensatory responses to the pandemic included at the behavioral level a greater number of simultaneously practiced measures to prevent infection. However, the resource for an extensive increase in the number of protective measures among health-care professionals is limited. The medical workers in different stages of our study equally practiced routine preventive measures. However, self-isolation, the most effective measure of protection against coronavirus infection,[32] was not available to them due to professional duties. In the context of exhausting the battery of behavioral self-defense measures, the respondents experienced a breakdown in the mechanisms of psychological adaptation to a pandemic, which was clearly demonstrated in the sub-cohort of respondents who practiced the maximum number of infection prevention measures. They reported higher stigmatization of patients with COVID-19.

An alternative type of health-care workers response to the spread of COVID-19 was characterized by an increase in the stigmatization of patients, combined with the maximum number of practiced protective measures against infection with a significantly lower level of psychological stress. The increase in stigmatization attitudes turned out to be associated most of all with the fear of medical workers for their own lives.

Limitations

The results of the study were obtained on the basis of self-reports. In the research sample, women were more prevalent: 75% of physicians and 95% of nurses – the trend similar to the regular structure of Russian health-care system. Nevertheless, the unequal representation of both sexes in the cohort limits the conclusions about the specific reactions to a pandemic in men and women. Of the medical specialties, psychiatrists were most prevalent in the sample. This could have a significant effect on the average stigmatization rates in the physicians' sub-cohort because psychiatrists are more familiar with the concept of stigma.

At the first stage of the study, we did not consider the data on the contact of medical workers with patients with COVID-19 and self-infection. Despite the fact that the marital status was considered, we did not specify whether the respondents live permanently with elderly people, people with chronic illnesses, or children, which could affect their stress levels. The data obtained during the study (specifics of somatic diseases, a region of residence, and the current level of the epidemic process) were not considered in the current analysis because they require further dynamic evaluation.

CONCLUSION

Russian health-care workers in the extraordinary situation of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated similar psychological problems of medical workers worldwide. However, their manifestations of distress had specific dynamics. While there was a decrease in the level of psychological stress in medical workers, their devaluation/discrimination scores of individuals with respiratory symptoms increased over time. Thus, administrative strategies on the organization of workloads, workspaces, and the psychological assistance cannot be based only on the average stress severity scores and should consider factors predisposing to the distress (age, the duration of work experience, level of education, marital status, etc.). The risks of stigmatization attitudes of health workers toward patients also should be considered and properly addressed. In order to improve the adaptation of health workers and maximize the safety of their psychological/mental health during the pandemic, it is appropriate to leave a part of medical workers in the reserve in order to rotate personnel that impedes the failure of their adaptation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nongovernmental organization “Russian Society of Psychiatrists,” the Interregional Professional Union “Physicians' Alliance,” the educational portal “Psychiatry and Neurosciences,” and the information portal “Fontanka.”

Appendix 1: Stress-assessment questionnaire associated with the new pandemic infection COVID-19

-

Sociodemographic data

- Sex (male/female)

- Age

- Education level

- Family status

- Occupation

- City of residence

- What somatic disorders do you have (nothing or list)

- Medical specialty

- Working experience in medicine

Distress associated with COVID-19

| a) During the last 7 days I track COVID-19 information in the media and on the Internet |

|---|

| 8) Hourly |

| 7) 4-5 times a day |

| 6) 2 times daily (in the morning and in the evening) |

| 5) 1 time daily |

| 4) 4-5 times a week |

| 3) 2-3 times a week |

| 2) Once |

| 1) Never |

| b) In relation to the announced coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), you are most concerned about | ||

|---|---|---|

| Definitely not | Definitely yes | |

| Contagiousness of the virus | ||

| Risk of isolation | ||

| Absence of specific treatment for COVID-19 | ||

| Fear for own life | ||

| Risk to the lives and health of relatives | ||

| Possible financial difficulties | ||

| Severe social consequences | ||

| Lack of safety equipment for sale | ||

| Possible lack of medication for daily intake | ||

| Impossibility of traditional way of life | ||

| c) What methods of disease prevention do you use? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Wearing a mask or respirator | ||

| Use of gloves | ||

| Use of antiseptics | ||

| Hand washing | ||

| Social distance | ||

| Self isolation | ||

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 30]. Https://www.who.int . Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regardingthe-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- 2.Huang J, Liu F, Teng Z, Chen J, Zhao J, Wang X, et al. Care for the psychological status of frontline medical staff fighting against COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 3] Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa385. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1055–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:233–40. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua SE, Cheung V, Cheung C, McAlonan GM, Wong JW, Cheung EP, et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:391–3. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramaci T, Baratucci M, Ledda C, Rapisarda V. Social Stigma during COVID-19 and its Impact on HCWs Outcomes. Sustainability. 2020;12:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blixen CE, Kanuch S, Perzynski AT, Thomas C, Dawson NV, Sajatovic M. Barriers to self-management of serious mental illness and diabetes. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40:194–204. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.40.2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonadonna LV, Saunders MJ, Zegarra R, Evans C, Alegria-Flores K, Guio H. Why wait? The social determinants underlying tuberculosis diagnostic delay. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vodopjanova NE. Psihodiagnostika Stressa SPb: Piter. 2009:1–336. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Link B, Cullen F, Frank J, Wozniak J. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. Am J Soc. 1987;92:1461–500. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorokin MYu, Kasyanov ED, Rukavishnikov GV, Makarevich OV, Neznanov NG, Lutova NB, et al. Structure of anxiety associated with COVID-19 pandemic: The online survey results. Bull RSMU. 2020;3:70–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Y, Wang J, Yang Y, Wang Z, Wang G, Hashimoto K, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of medical staff in Chinese psychiatric hospitals regarding COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020;4:100064. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan R, Zhang L, Pan J. The anxiety status of Chinese medical workers during the epidemic of COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17:475–80. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1745–52. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorokin MYu, Kasyanov ED, Rukavishnikov GV, Makarevich OV, Neznanov NG, Semyonova NV, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers in Russia. Meditsinskaya Ethica [Medical Ethics] 2020;2:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Xu QH, Wang CM, Wang J. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112955. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Frank E, Zhao Z, Chen L, Wang Z, Burmeister M, et al. Mental health of young physicians in China during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010705. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taghizadeh F, Hassannia L, Moosazadeh M, Zarghami M, Taghizadeh H, Dooki AF, et al. Anxiety and depression in health workers and general population during COVID-19 epidemic in IRAN: A web-based cross-sectional study. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 27];medRxiv. 2020 20089292:21. doi: 10.1002/npr2.12153. Available from: https://wwwmedrxivorg/content/101101/2020050520089292v1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharyya R, Bhattacharyya S, Gupta S, Das S, Banerjee BB. Attitude, practice, behavior, and mental health impact of COVID-19 on doctors. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:257–65. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_333_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke M, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller S. COVID-19-pandemie: Belastungen des medizinischen personals. Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47:190–7. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, Lang Q, Liao C, Wang N, et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1002–9. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Özdin S, Bayrak Özdin Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:504–11. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chew NW, Lee GK, Tan BY, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;S0889-1591:30523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:93–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen S, Karaca-Mandic P, Georgiou A. Association of stay-at-home orders with COVID-19 hospitalizations in 4 states. JAMA. 2020;323:2522–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]