Abstract

Background

The covid-19 pandemic has dramatically changed lives of residents and medical students. In particular, the learning process has undergone widely changes, especially due to the rules of social distancing which have forced universities and various institutes to modify lessons, work shifts and internships.

Purpose

The purpose of our review is to evaluate how the various institutes have faced the covid-19 emergency and guaranteed the perpetuation of the learning process of resident and students.

Methods

A comprehensive search of the medical literature in PubMed and Google Scholar was performed including all the works explaining how the institutes have reorganized teaching for resident and undergraduate students.

Main findings

The use of internet for the dissemination of teaching material and educational meetings has built bridges, albeit virtual, between resident and teachers. New techniques for teaching and conducting exams have been introduced. The rotating team system allowed the continuation of the teaching activity in safety.

Conclusion

Thanks to remodulation of the teach modalities, the massive use of internet platforms, a wise distribution of work shifts, and others, universities and hospitals have not only reduced the impact on the learning process of resident and students but also turn this pandemic into a moment of personal and professional growth for the new generation of healthcare professionals.

Keywords: Covid-19, Learning, Resident, Trainee, Pandemic, Undergraduate students

Introduction

The novel Covid-19 pandemic marked our lives in an indelible way, changing the reality we were used to. It affected negatively the educational training for all students worldwide; Given the social distancing recommendations, the Coronavirus emergency has led to significant modification within hospitals, such as limiting the presence of residents who are on duty, cancelling elective procedures, decreasing the volume of acute care surgery following surgical professional societies guidelines, and cancelling lectures and educational conferences to adhere to social distancing recommendations.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Regarding teaching, in-person academic activities, including face-to-face teaching, and simulation laboratories have been interrupted, along with an interruption of the clinical rotation within the different areas of the same institution. The current pandemic emergency has imposed significant loads on universities and hospitals to promote continued safety, education, and quality patient care.1 , 5 , 6 The present article evaluated the methods used by the various institutions to overcome the difficulties that have arisen to allow continuation of training courses medical students and post-graduate medical trainees and identify possible differences between the various institutes.

Methods

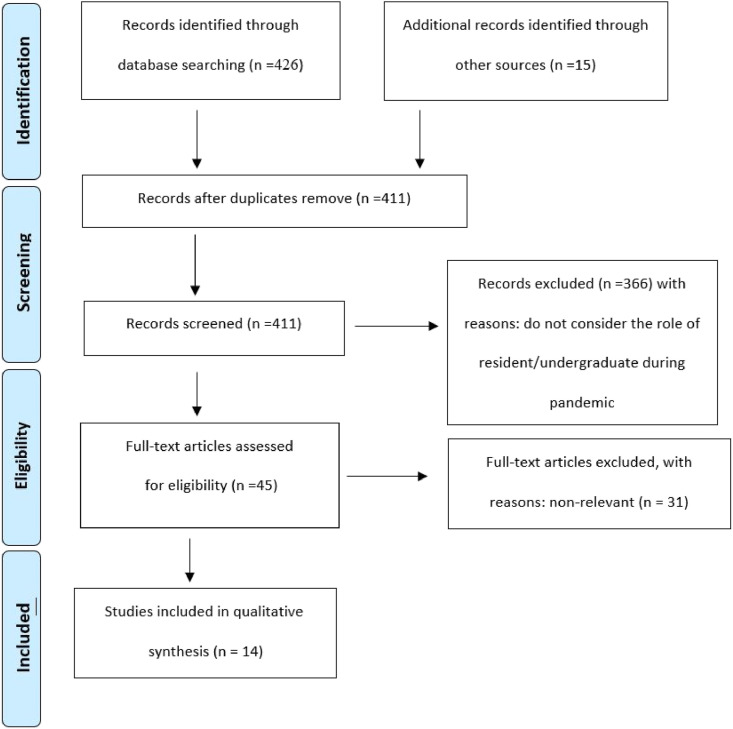

A comprehensive search of the medical literature in PubMed and Google Scholar was performed. The following Keywords were used in combination: “Covid-19/coronavirus, SARS/CoV-2, pandemic, virtual, rotation, telemedicine, skills, learning, distance, training, students, resident/trainee, webinar, undergraduate students”. We considered for inclusion only studies that clearly stated the methods and techniques used by institutes to ensure the safety and continuous education of its own students. Reviews, letters, expert opinion and commentaries were not eligible for inclusion. The Prisma guidelines were followed (Fig. 1 ). The results of the literature search are shown in Table .1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Residency covid-19 training impact on surgical, medical and services specialities.

| Authors (and affiliations) | Specialty | Learning tools | Reorganization of work shifts | Assessment method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okland et al.24 Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA; |

Otolaryngology | Surgical simulation, 3D printing, Surgical kits, 3D Take-home simulation | – | Pre and post surveys are provided to the residents to evaluate the utility of the exercise |

| Leck et al.33 Division of Neurosurgery, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. |

Neurosurgery |

|

Two separate teams of residents work 6 days on and 6 days off | – |

| Kogan et al.28 Rush University Medical Center, Chicago |

Orthopaedic & traumatology | Virtual learning – independent study – surgical simulation | Two groups of 15 resident: Home Team and Hospital Team. After a 2-week period, the Hospital team switches with the Home team, helping to ensure that at least half of the residents are healthy at any one time. | The Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS), Global Rating Scales, and ABOS Surgical Skills Assessment Program |

| Self-reported resident questionnaires | ||||

| Schartw et al.22 Department of Orthopaedics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia |

Orthopaedics & Traumatology | - Daily one-and-a-half-hour collaborative, faculty-ledinteractive learning sessions on a topic- musculoskeletal subspecialty visits performed via video-enabled tele-medicine- academic endeavors: clinical research projects, grant writing, quality improvement ventures | Two teams structured as “active-duty inpatient” and “remotely-working.” | Mcq about daily topic |

| Sabharwal et al.23 The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland |

Orthopaedic & Traumatology |

|

– | Chief resident-led teleconference: question review format, on earlier faculty-led topic completed independently |

| 2 teams: Team A (remote team) and Team B (on duty team) at each of 2 main hospitals that alternate clinical in-hospital duty every 14 days. | In-training exam question completion and review (50 questions) | |||

| Malhotra et al.14 All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India |

Orthopaedic & Traumatology | Online lectures, Seminars and Journal Clubs with live streaming and interaction | Divided into multiple teams (Teams A & D rotate with teams B & C every 4 weeks) Each team comprise of senior and junior level residents One team is assigned for COVID care 25% residents are kept as reserve Others manage operative, inpatient and outpatient services on rotational basis | – |

| Nassar et al.25 Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Pacific St, Seattle, WA |

General surgery | Inpatient Care: This team performs all in patient clinical duties, including daily rounds, new consult staffing, admissions and discharges, and documentation. Operating Care: This team coordinates the operative care of patients and participates in the operations. Clinical Care: This team participates in outpatient clinics through telehealth The 3 teams would theoretically never physically interact |

Three new larger teams called Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie. Each new team consisted of resident of all ranks, complemented by nurse practioners. The clinical workloaded and mandatory staffing needs were similarly divided into 3 patient care domains: inpatient, operative, and clinic |

– |

| Varga et al.26 Cleveland Clinic, Akron General Urology Program, Akron, OH |

Urology | 3-h daily check.in conducted on virtual platform:

|

|

After each meeting, a summary email is sent by program director or chief residents to all members of the residency program, serving both as a debriefing as well as a tracking system of our academic progress during this challenging time. |

| Chick et al.12 Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, Texas; and †University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California |

Surgical specialities | Flipped Virtual Classroom model | Avoid gatherings >10 people | – |

| Online practice questions | Avoid rotations between different sites | |||

| Academic conferences via teleconference | Cancel or postpone elective operations in a hospital setting | |||

| Telehealth clinics with resident involvement | Minimize nonessential personnel in the operating room | |||

| Facilitated use of surgical videos | Maintain disaster management and mass casualty triage principles | |||

| Almarzooq et al.11 Brigham and Women's Hospital, Heart and Vascular Center and Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis Street, Boston, Massachusetts |

Cardiology | Virtual educational Environment: Virtual Learning Platform | – | Mcq |

| Conroy et al.9 Yale University School of Medicine (MC, HA), New Haven, CT |

Psychiatry | AAGP COVID Curriculum: 30 online video modules, each delivered by an expert in the field. Lecture topics include a comprehensive range of subjects related to the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of the older adult patients, along with special topics, such as cultural psychiatry and a Psychiatry Resident-In-Training Examination (PRITE) review | – | Trainees will be able to view each lecture and receive a certificate of completion regardless of their decision to complete the survey questions |

| Recht et al.10 Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, New York |

Radiology | ‘'Simulated'' daily readout (SDR): SDR provided the opportunity to present uncommon pathology with high educational impact to the residents who normally would only read about such entities but would not encounter them in daily practice due to low disease prevalence. | The number of cases on each worklist varied according to the training level of the residents and the week of the rotation three | – |

| Barberio et al.8 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padua, Padua, Italy |

Gastroenterology | endoscopic training

|

– | |

| Pollom et al.30 Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, Stanford, California |

Oncology | Didactic sessions include lectures, case-based discussions, treatment planning sessions in Eclipse and Precision, and lectures adapted from the Radiation Oncology Education Collaborative Study Group curriculum material Medical students attend departmental quality assurance rounds, cancer center seminars, and multidisciplinary tumor boards that do not conflict with clerkship activities, which are all currently offered in a virtual environment. |

first week: didactic sessions second week: virtual clinics and give talks to the department For the virtual clinic experience, students are assigned to different services in teams of 2. Students work with the resident and faculty of their assigned service to see and present virtual clinic patients during the second week of the clerkship. |

Complete pre- and postcourse self-assessments Attend didactic sessions and complete postlecture assessments Participate in virtual clinic and submit completed consult notes Give a journal club talk to the department |

Results

After removal of duplicate records, 411 articles were assessed. Then, following inspection of the title and the abstracts, 366 articles were excluded because although considering hospital reorganization during covid-19 they do not focus on resident or undergraduate. A further screening excluded another 31 articles because they do not specifically consider how the teaching of trainee or undergraduate students has changed. A total of 14 articles were included.

Resident education

Given the quick spreading of the SARS-CoV-2 around the world, and the introduction of social distancing measures, many educational systems faced a mandatory closure of in-person activities. All universities suspended their frontal teaching, providing online lecture to guarantee students’ teaching and their right to study.7 The internet has represented the keystone to produce the necessary connections between students and teachers. We assisted to a transitional paradigm from an in-person training to an online-training. The pivot of this system was on-line meetings, which became the only moment of discussion and debate. Numerous platforms have been used for this purpose, including ZOOM™, GOTOMEETING™, MICROSOFT TEAM™ and many others. During the lockdown period, there was constant improvement of these programmes, improving their versatility and accessibility to students and teachers. These meetings gave the opportunity to learn and discuss topics between students, trainee, residents and clinical and academic staff, or webinars from third party organisations.8, 9, 10, 11 In this scenario, an innovative teaching method arose: the flipped classroom strategy. Using this innovative teaching method, learners were provided with didactic material, in the form of a pre-recorded video lecture, which they could watch prior to the online meeting. Students expressed high levels of satisfaction with pre-class video lectures because the videos can be accessed at any time and as often as they desire. Students also highly regarded the use of small group discussion-based activities in flipped classroom face-to-face sessions because these sessions increase their motivation to learn, and enhanced their level of engagement and interest in the subject matter.12 , 13 Especially for surgical trainee interactive platforms provide surgical anatomy reviews, surgical procedure walkthroughs, practice test questions, and intricate patient cases.12, 13, 14 However, their effectiveness in improving surgical performance remains limited.15, 16, 17, 18 The most popular video search engine for surgical trainees is YouTube™, whereas specialists tend to rely on videos from specialist surgical societies.16 , 19 Caution should be exerted when choosing videos, because there is no current peer-review process for publishing medical videos online, with many top-ranked videos showing suboptimal technique.20 Though virtual learning is able to support certain aspects of surgical education, it cannot obviously bridge certain gaps.12 , 21, 22, 23 It is difficult for the current virtual platforms to address the lack of intra-operative experiences. Models and instruments, such as suturing kits with felt or silicone “tissue” or FLS (Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery) box trainers, can be borrowed for technical practice. Written or verbal feedback can be provided remotely, either through faculty review of uploaded recordings or hosted virtual sessions in which residents focus their camera on their technical performance for faculty feedback in real-time.20 , 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Some obstacles related to the digital revolution in medical learning have been evidenced, including some teachers and educators struggling with new technologies, participants with poor bandwidth connections, and difficulties in viewing images. However, these limitations can be overcome with an investment of time and effort by staff suppliers who are familiar with these techniques.29

At the basis of surgical and medical education there is the theory of self-directed learning. In this transition period, trainees can use this time to reflect on their personal learning methodologies, establish a goal, such as improved in-service exam performance, or developing a deeper understanding of a certain topic using review materials textbooks, online review articles, and previously described virtual educational modules. In addition, students can use the time available for setting up or completing academic work and research projects.8 , 9 , 12, 13, 14 , 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 , 28 With regard to the evaluation methods, the most used are the multiple-choice questions concerning the topics covered during the lecture of the day or of the previous days accompanied by the discussion among the residents. This represents a fundamental moment in the path the learning of these students during the lockdown period, as it keeps attention alive and allows the comparison between resident with different attitudes and interests and at the same time helps to develop the critical sense necessary to face the more and more challenges.11 , 22 , 23 , 30

Impact Covid-19 on surgical assistance

In accordance with international guidelines, elective surgery was suspended, and only emergent and urgent cases could be operated. Consultations were accomplished mostly though a telemedicine platform. Exception was made for those patients with suspected of acute wound healing problems. Participation in these consultations provides continuity of clinical education without additional risk.31 , 32 The other operative cases were staffed by no more than a single faculty and a single resident to limit exposure. Consequently, the number of residents physically present in hospitals decreased significantly, helping to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Residents were divided into two or more groups: the home group focused on virtual teaching, the in-service group and sometimes a reserve group (composed of two or three resident who stayed at home and were ready to replace a colleague on duty in the event of illness). Trainees rotated from one group to the other every two or more weeks. The duties of in-service resident varied from assisting in ward rounds, helping to implement ventilator protocols, providing general intensive care unit care, responding to ancillary staff queries, providing updates to the family of the Covid-19 patient, and monitoring overall patient status. To protect residents, full personal protective gear respirator masks, eyewear/face-shields, and full head/body gowns was provided to each resident and faculty, along with infrared laser thermometers to record temperatures at the beginning and end of shifts.16 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 35 , 36

Impact of Covid-19 impact on undergraduates

During the Covid-19 lockdown, the life of an undergraduate medical student also underwent considerable upheaval. Those students away from their families and hometowns found themselves alone in full lockdown. Their education was interrupted, experiencing intense fear caused by uncertainty. More than half of medical students felt mentally unwell, as the corona virus outbreak determined high levels of anxiety.34

The Covid-19 pandemic introduced of new methods to provide education to medical students as well. Formal lectures were quickly converted into webinars available online, to be reached via the platforms mentioned in the previous section, in real time or recorded for later use by students wherever they were.35 Current online webinars include key clinical conditions, case studies, didactic lectures and examination questions.

The transition to online medical education also promoted changes in examination methods. Following the recent success of Imperial College London's first ever online exam for final year students, other medical schools adopted a similar approach to ensure students remain engaged with their studies, with many universities adopting an open-book examination (OBE) approach. This approach allows students to use all their material (books, notes etc.) during the test, and represent an alternative from previous exam-hall settings (closed book). OBEs have been reported to reduce student anxiety,36 although it is not possible to generalize as some students often overestimate the help they can receive from the open book with a detrimental effect on the retention of notions and performance on exams. In addition, anxiety levels do not always have a negative effect on the student's performance, sometimes helping them to try their best and develop a stronger and more confident personality. However, with a global level of heightened fear and apprehension during the current COVID-19 pandemic, an approach to examining students that can minimise the symptoms of stress is welcomed.38

During the lockdown period, some universities recruited students for hospital-based roles as either students or early graduated frontline workers, while others prohibited any patient interaction.37 , 38 Although medical students are a commendable source of help, their involvement must be carefully evaluated and their introduction to actual hospital clinical must be strictly controlled. Through their clinical attachments, they operate passively, shading teams, taking stories and observing procedures. Therefore, a well-structured program producing a stable learning environment does not guarantee that students will acquire the confidence and skills necessary to function properly during a pandemic; the lack of required knowledge and capability placed students, and patients, at risk during disaster situations.39 , 40 Similar concerns are raised with the use of spontaneous volunteers in post-disaster situations by non-governmental voluntary organisations.41 With constrained services, and national pleas for volunteers, there is potential for students to be misguided in their choice. In such situations, students can act as vectors for viral transmission, consume personal protective equipment and place an additional burden on teaching physicians.42 Medical education alone does not justify these risks. However, the training of young medical students can benefit from the considerable resources offered by virtual learning and independent study.43 , 44, 45, 46

Limitations

This work has several limitations. Firstly, the articles considered do not systematically analyse the characteristics and results of the measures introduced in this pandemic period, but merely report their experiences in a narrative manner. Second, most of the articles describe the organization of institutes of excellence in USA whose organization and economic availability is well above average, with few detailed testimonials from other countries. In some environments, internet connection does not reach the speed and stability required to guarantee the student an acceptable quality standard. For this reason, it will be the task of national governments to strengthen and extend broadband connections as much as possible in territories where distribution is poor. The extension of the network combined with the enhancement of educational systems, the use of virtual simulators, the establishment of databases of online lectures, the enhancement of access to on line libraries, will certainly require economic efforts that are not always sustainable in all parts of the world.14 , 22 , 27 , 36

Conclusion

The work highlights first the promptness and efficiency with which medical education institutes managed to organize the teaching and the shift of postgraduate trainees allowing the necessary decrease in the presence of staff within hospitals, without cutting the necessary resources in this pandemic period. The use of internet for the dissemination of teaching material and educational meetings has built bridges, albeit virtual, between resident and teachers. The rotating team system has made it possible to achieve a balance between the safe and isolation of the resident and a certain amount of in-service hours. This unprecedented circumstance will change the way in which we deliver medical teaching and represents an opportunity for residents not only to focus on the theoretical aspects of their discipline but also a invaluable education in crisis management on a large scale and an opportunity to grow a common sense of belonging to face such adversities. However, maintaining the effective organization described will require continuous innovation and cooperation on the part of educational program directors, and leadership on the part of our professional societies to maintain rigorous standards of education and training for resident and medical student.

References

- 1.An T.W., Henry J.K., Igboechi O., Wang P., Yerrapragada A., Lin C.A. How are orthopaedic surgery residencies responding to the COVID-19 pandemic? An assessment of resident experiences in cities of major virus outbreak. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020 Aug 1;28(15):e679–e685. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal P., Bingemann T.A., Greenhawt M., Mosnaim G., Nanda A., Oppenheimer J. Clinician wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic: extraordinary times and unusual challenges for the allergist/immunologist. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Jun;8(6):1781–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.001. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrel M.N., Ryan J.J. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 2020 Mar 31;12(3):e7492. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed H., Allaf M., Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;20(7):777–778. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30226-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cipollaro L., Giordano L., Padulo J., Oliva F., Maffulli N. Musculoskeletal symptoms in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) patients. J Orthop Surg. 2020 May 18:15. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01702-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coe T.M., Jogerst K.M., Sell N.M., Cassidy D.J., Eurboonyanun C., Gee D. Practical techniques to adapt surgical resident education to the COVID-19 era. Ann Surg. 2020;72:e139–e141. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sethi B.A., Sethi A., Ali S., Aamir H.S. Impact of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals. Pak J Med Sci. 2020 May;36(COVID19-S4):S6–S11. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barberio B., Massimi D., Dipace A., Zingone F., Farinati F., Savarino E.V. Medical and gastroenterological education during the COVID-19 outbreak. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun 1:1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0323-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy M.L., Garcia-Pittman E.C., Ali H., Lehmann S.W., Yarns B.C. The COVID-19 AAGP online trainee curriculum: development and method of initial evaluation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2020 Sep;28(9):1004–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Recht M.P., Fefferman N.R., Bittman M.E., Dane B., Fritz J., Hoffmann J.C. Preserving radiology resident education during the COVID-19 pandemic: the simulated daily readout. Acad Radiol. 2020 Aug;27(8):1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almarzooq Z.I., Lopes M., Kochar A. Virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a disruptive technology in graduate medical education. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 May 26;75(20):2635–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hew K.F., Lo C.K. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018 Mar 15;18(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramnanan C.J., Pound L.D. vol. 8. Dove Press; 2017. Advances in medical education and practice: student perceptions of the flipped classroom; pp. 63–73. (Advances in medical education and practice). [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chick R.C., Clifton G.T., Peace K.M., Propper B.W., Hale D.F., Alseidi A.A. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020 Jul 1;77(4):729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almaiah M.A., Al-Khasawneh A., Althunibat A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Inf Technol. 2020 May 22:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malhotra R., Gautam D., George J. Orthopaedic resident management during the COVID-19 pandemic – AIIMS model. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020 May;11:S307–S308. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pape-Koehler C., Immenroth M., Sauerland S., Lefering R., Lindlohr C., Toaspern J. Multimedia-based training on Internet platforms improves surgical performance: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2013 May;27(5):1737–1747. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2672-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaffar A.A. YouTube: an emerging tool in anatomy education. Anat Sci Educ. 2012 Jun;5(3):158–164. doi: 10.1002/ase.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mota P., Carvalho N., Carvalho-Dias E., João Costa M., Correia-Pinto J., Lima E. Video-based surgical learning: improving trainee education and preparation for surgery. J Surg Educ. 2018 Jun;75(3):828–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong C., Goh P.S. Twelve tips for the effective use of videos in medical education. Med Teach. 2015 Feb;37(2):140–145. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.943709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapp A.K., Healy M.G., Charlton M.E., Keith J.N., Rosenbaum M.E., Kapadia M.R. YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation. J Surg Educ. 2016 Dec;73(6):1072–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoopes S., Pham T., Lindo F.M., Antosh D.D. Home surgical skill training resources for obstetrics and gynecology trainees during a pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul;136(1):56–64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordano L., Oliviero A., Peretti G.M., Maffulli N. The presence of residents during orthopedic operation exerts no negative influence on outcome. Br Med Bull. 2019 19;130(1):65–80. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz A.M., Wilson J.M., Boden S.D., Moore T.J.J., Bradbury T.L.J., Fletcher N.D. Managing resident workforce and education during the COVID-19 pandemic: evolving strategies and lessons learned. JBJS Open Access. 2020 Jun;5(2) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabharwal S., Ficke J.R., LaPorte D.M. How we do it: modified residency programming and adoption of remote didactic curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okland T.S., Pepper J.-P., Valdez T.A. How do we teach surgical residents in the COVID-19 era? J Surg Educ. 2020 Sep-Oct;77(5):1005–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nassar A.H., Zern N.K., McIntyre L.K., Lynge D., Smith C.A., Petersen R.P. Emergency restructuring of a general surgery residency program during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: the university of Washington experience. JAMA Surg. 2020 Jul 1;155(7):624–627. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargo E., Ali M., Henry F., Kmetz D., Drevna D., Krishnan J. Cleveland clinic akron general urology residency program's COVID-19 experience. Urology. 2020 Jun;140:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aiyer A.A., Granger C.J., McCormick K.L., Cipriano C.A., Kaplan J.R., Varacallo M.A. The impact of COVID-19 on the orthopaedic surgery residency application process. JAAOS - J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28 doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kogan M., Klein S.E., Hannon C.P., Nolte M.T. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAAOS - J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020 Jun 1;28(11):e456. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehrlich H., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. We asked the experts: virtual learning in surgical education during the COVID-19 pandemic—shaping the future of surgical education and training. World J Surg. 2020 Jul 1;44(7):2053–2055. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05574-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollom E.L., Sandhu N., Frank J., Miller J.A., Obeid J.-P., Kastelowitz N. Continuing medical student education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: development of a virtual radiation oncology clerkship. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 May 19 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machado Júnior A.J., Pauna H.F. Distance learning and telemedicine in the area of Otorhinolaryngology: lessons in times of pandemic. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol Engl Ed. 2020 May 1;86(3):271–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon Y.S., Tabakin A.L., Patel H.V., Backstrand J.R., Jang T.L., Kim I.Y. Adapting urology residency training in the COVID-19 era. Urology. 2020 Jul;141:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leck E.D., MacLean M.A., Alant J. A Canadian perspective on coronavirus disease-19 and neurosurgical residency training. Surg Neurol Int. 2020;11:125. doi: 10.25259/SNI_250_2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong C., Tay W., Hap X., Chia F. Love in the time of coronavirus: training and service during COVID-19. Singap Med J. 2020 Jul;61(7):384–386. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapasia N., Paul P., Roy A., Saha J., Zaveri A., Mallick R. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020 Sep 1;116:105194. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kay D., Pasarica M. Using technology to increase student (and faculty satisfaction with) engagement in medical education. Adv Physiol Educ. 2019 Sep 1;43(3):408–413. doi: 10.1152/advan.00033.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stowell J.R., Bennett D. Effects of online testing on student exam performance and test anxiety. J Educ Comput Res. 2010;42(2):161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iacobucci G. Covid-19: medical schools are urged to fast-track final year students. BMJ. 2020 Mar 16:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.COVID-19: How the virus is impacting medical schools. American Medical Association.

- 42.Mortelmans L.J.M., Bouman S.J.M., Gaakeer M.I., Dieltiens G., Anseeuw K., Sabbe M.B. Dutch senior medical students and disaster medicine: a national survey. Int J Emerg Med. 2015 Sep 3:8. doi: 10.1186/s12245-015-0077-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gouda P., Kirk A., Sweeney A.-M., O'Donovan D. Attitudes of medical students toward volunteering in emergency situations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020 Jun;14(3):308–311. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauer L.M., Catlett C., Tosatto R., Kirsch T.D. The utility of and risks associated with the use of spontaneous volunteers in disaster response: a survey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2014 Feb;8(1):65–69. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2014.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller D.G., Pierson L., Doernberg S. The role of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Apr 7:M20–M1281. doi: 10.7326/L20-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandhu P., de Wolf M. The impact of COVID-19 on the undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2020 May 13;25(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1764740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]