Abstract

Background:

Students pursuing higher education are subject to high stress levels which could be associated with dysfunctional coping. Maladaptive coping is known to be operative in manifesting as psychopathology as depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse. This study aimed to elaborate the psychological morbidity among professional undergraduates in general and medical students in particular, its evolution over the years and its psychosocial correlates.

Methodology:

The study examined medical students (n = 202) and age-matched engineering students (n = 145) belonging to the first and final year for psychological stress and coping, educational stress, domestic and professional concerns, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Psychometric scales along with demographic questionnaire were used to assess and quantify stress and psychological morbidity.

Results:

Medical students had higher levels of stress (psychological and education related) and higher psychological morbidity (depression and anxiety). Stress scores correlated positively with depression and anxiety scores and negatively with substance use score. Psychological stress other than educational stress was noted to be predictors of alcohol use in the sample.

Conclusion:

Our study elucidates that medical students face higher levels of psychological and education-related stressors and have higher levels of psychological morbidity than students from engineering colleges. Psychoactive substances are used as a form of self-medication to alleviate stress.

Keywords: Anxiety, coping, depression, educational stress, medical students, substance use

The goal of medical education is to train knowledgeable, competent, and professional physicians equipped to care for the infirm, advance the science of medicine, and promote public health. Medical students face a large number of stressors in their daily lives. Stress in medical school add onto the usual stress that all students experience. There are various stressors among students, for example, physical, psychological, familial, financial, social, academic, and clinical.[1] Majority of the studies have revealed a high prevalence of psychological distress in the medical students.[2,3,4,5,6] Moreover, the stress level is higher in medical students compared to the students in other courses.[7,8] A systematic review[9] estimated a prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms of 28.8% in the medical workforce (ranging from 20.9% to 43.2%). A recent systematic review[10] from India noted that the pooled prevalence rate of depression was 39.2%, that for anxiety was 34.5%, and for stress the rate was 51.3%. The final year students were significantly more stressed than the 1st year students,[11,12] and the risk factors associated with higher perceived stress were female gender,[13] vastness of academic curriculum, fear of failure or poor performance in the examination, lack of recreation, academic curriculum, frequency of examinations, performance in examinations, competition with peers, high parental expectations, and psychosocial factors.[12,14,15] A systematic review of substance use among medical students[16] noted that, with the exception of alcohol in some areas of the Western world, medical students use substances less than university students in general and the general population. The substances used were mainly alcohol (24%), tobacco (17.2%), and cannabis (11.8%). The use of hypnotic and sedative drugs was also common (9.9%) with the rates of use of other drugs being low (stimulants [7.7%], cocaine [2.1%], and opiates [0.4%]). Very high levels of substance use (up to 91.3% alcohol users and 26.2 cannabis users) were noted in a recent study among medical students in 49 medical colleges.[17] A recent Indian study,[18] however, found the prevalence of substance abuse to be 20.43% among medical students with an increase in use observed in the latter years of medical education and the most common reasons for substance use was relief from psychological stress (72.4%). Most of the above studies reported prevalence and factors associated with stress, dysfunctional coping, and psychological morbidity among medical students. The study sought to elaborate the psychological morbidity among professional undergraduates in general and medical students in particular, its evolution over the years in medical school and its psychosocial correlates. Engineering colleges provide an environment similar to the medical colleges (both being professional colleges) that may be used for the comparison.

METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional study was carried out at a medical college, with sample population being all the available 1st year (n = 108) and final year (n = 94) students. Undergraduates of first (n = 73) and final year (n = 72) from an engineering college in the same city run by the same administration and providing similar academic and hostel facilities were sampled for comparison. Approval was taken from the administration in both the colleges; informed consent was obtained from the students, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at the medical college. The primary hypothesis is that educational stress increases from 1st to the 4th year of college and is associated with increase in psychological morbidity.

The students were administered the following set of psychometric scales:

Demographic questionnaire

It consisted of a number of questions pertaining to the individual’s personal sphere as well as his family. It also enquired about the habits pertaining to substance use in the family, history of psychiatric and physical illnesses, recent demise in the family or the social circle, interpersonal relationships, and certain concerns of the individual regarding his stay in the college (measured on a Likert scale).

Self Rating Depression Scale of Zung

The Zung’s self-rating depression scale (SDS) used to screen adults for the potential presence of depressive disorders,[19] consisting of 20 questions comprising of 10 symptomatically negative and a similar number of positive questions based on a Likert scale scored from 1 to 4. The cutoff Zung’s SDS index for possible depressive disorders used in this study is 50.

Self Rating Anxiety Scale of Zung

The Zung’s Self-Rating Anxiety scale (SAS)[20] is a self-rating scale used to screen adults for the potential presence of anxiety disorders consisting of twenty questions related to the frequency of various symptoms. The cutoff SAS index for possible anxiety disorders used in this study is 45.

Rhode Island Stress and Coping Inventory

The Rhode Island Stress and Coping Inventory (RISCI)[21] is a measure for examining perceived stress and coping independent of specific stress situations. It consists of 12 items evaluated on a Likert scale measured from 0 to 5 containing 7 items to measure stress and 5 items for coping.

Higher Education Stress Inventory

The Higher Education Stress Inventory (HESI)[3] is an inventory to measure the stress of higher education among students. The HESI is designed to capture a wide variety of stressful aspects and is applicable within different higher educational settings. It comprises 33 statements indicating the presence or absence of stressful aspects, to be rated on a 4-point Likert scale.

Michigan Alcohol Screening Test

The Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST)[22] is a 25-item screening instrument designed to identify and assess alcohol abuse and dependence. The optimal cutoff for the MAST is 13, however, a lower cut off of >5 has been used in this study to identify harmful drinking.

Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale

The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS)[23] is a multifactorial instrument to assess tobacco dependence. The 19-item scale is evaluated on a Likert scale with values ranging from 1 to 5 capturing the essential elements of excessive tobacco use. A cutoff score of 40 was used for assessing possible nicotine dependence.

Drug Abuse Screening Test

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)[24] is a standard screening test for drug use comprising of 28 questions to be answered as Yes or No. A score of >5 indicates a drug problem.

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normality. The qualitative data were evaluated using the Chi-square test, whereas the quantitative data were tested using parametric tests. Linear regression was used to test the primary hypothesis. Statistical analysis was carried out using R version 3.5.0. Level of significance was kept at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The demographics of the sample population are tabulated in Tables 1–3. The medical students scored higher marks in Class 10th (χ2= −8.3, P < 0.01) and 12th (χ2= −5.2, P < 0.01), and their parents were also more educated than those in the engineering stream (P < 0.01) [Table 1]. With respect to substance, more number of fathers in the engineering cohort consumed alcohol than the medical students (Z = −4.32, P < 0.01). Within the medical stream, more number of 1st year had scored higher than the 4th year in Classes 10th (χ2 = 3.42, P < 0.01) and 12th (χ2 = 2.66, P < 0.01). Furthermore, parents of the 1st year were more educated and had higher income than those of the 4th year [Table 2]. Furthermore, more number of fathers and siblings of 4th year students consumed alcohol than among the 1st year. Within the engineering stream [Table 3], the students were similar in most respects, except father’s education where more number fathers of 4th year were postgraduates and alcohol use in father where 1st year had more number of fathers with alcohol use.

Table 1.

Demographic variation between the engineering and medical streams

| Variable | Engineering (n=145) | Medical (n=242) | Statistic (χ2) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20.0±1.93 | 20.2±1.73 | −1.1a | 0.27 |

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 119 | 157 | 1.0 | 0.32 |

| Females | 26 | 45 | ||

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Rural | 50 | 53 | 2.7 | 0.098 |

| Urban | 95 | 149 | ||

| Marks 10th | 80.7±9.19 | 87.6±6.32 | −8.3a | <0.01 |

| Marks 12th | 79.7±8.82 | 84.2±7.16 | −5.2 | <0.01 |

| Father’s education | ||||

| Middle school | 2 | 1 | 22.9 | <0.01 |

| High school | 13 | 8 | ||

| Intermediate | 22 | 10 | ||

| Graduate | 63 | 78 | ||

| Postgraduate | 45 | 105 | ||

| Father’s occupation | ||||

| Skilled workers | 35 | 4 | 65 | 0.16 |

| Clerical/shop | 13 | 55 | ||

| Semiprofessional | 44 | 99 | ||

| Professional | 53 | 44 | ||

| Father’s income (Rs.) | ||||

| 11,000-15,000 | 23 | 31 | 2.1 | 0.58 |

| 15,000-30,000 | 69 | 111 | ||

| >30,000 | 53 | 60 | ||

| Mother’s education | ||||

| Middle school | 27 | 12 | 20.8 | <0.01 |

| High school | 21 | 16 | ||

| Intermediate | 20 | 26 | ||

| Graduate | 42 | 81 | ||

| Postgraduate | 35 | 67 | ||

| Mother’s occupation | ||||

| Unemployed | 121 | 120 | 30.8 | <0.01 |

| Clerical/shop | 12 | 68 | ||

| Professional | 12 | 14 | ||

| Family history of depression | 2 | 6 | 0.9 | 0.28 |

| Family history of suicide | 2 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol use in father | 36 | 12 | 28.5 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use in siblings | 3 | 2 | 3.5 | 0.66 |

| Negative events | 46 | 61 | 1.9 | 0.17 |

Chi-square test. at-test

Table 2.

Demographic variation between the 1st and 4th year medical students

| Variable | Medical 1st year (n=108) | Medical 4th year (n=94) | Statistic (χ2) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 83 | 25 | 0.1 | 0.87 |

| Females | 74 | 20 | ||

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Rural | 23 | 85 | 2.93 | 0.06 |

| Urban | 30 | 64 | ||

| Marks 10th | 80.7±9.19 | 89.0±5.42 | 3.42a | <0.01 |

| Marks 12th | 79.7±8.82 | 85.4±6.52 | 2.66a | <0.01 |

| Father’s education | ||||

| Middle school | 0 | 1 | 9.6 | <0.01 |

| High school | 3 | 5 | ||

| Intermediate | 3 | 7 | ||

| Graduate | 36 | 42 | ||

| Postgraduate | 66 | 39 | ||

| Father’s occupation | ||||

| Skilled worker | 1 | 3 | 2.4 | 0.85 |

| Clerical/shop | 27 | 28 | ||

| Semiprofessional | 57 | 42 | ||

| Professional | 23 | 21 | ||

| Father’s income (Rs.) | ||||

| 11,000-15,000 | 11 | 20 | 5.16 | 0.03 |

| 15,000-30,000 | 61 | 50 | ||

| >30,000 | 36 | 24 | ||

| Mother’s education | ||||

| Middle school | 3 | 9 | 6.84 | 0.02 |

| High school | 8 | 8 | ||

| Intermediate | 12 | 14 | ||

| Graduate | 43 | 38 | ||

| Postgraduate | 42 | 25 | ||

| Mother’s occupation | ||||

| Unemployed | 70 | 50 | 3.58 | 0.06 |

| Clerical/shop | 33 | 35 | ||

| Professional | 5 | 9 | ||

| Family history of depression | 2 | 6 | 0.9 | 0.28 |

| Family history of suicide | 2 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol use in father | 36 | 12 | 28.5 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use in siblings | 3 | 2 | 3.5 | 0.66 |

| Negative events | 46 | 61 | 1.9 | 0.17 |

Chi-square test. at-test

Table 3.

Demographic variation between the 1st and 4th year engineering students

| Variable | Engineering 1st year (n=108) | Engineering 4th year (n=94) | Statistic (χ2) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 62 | 57 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| Females | 11 | 15 | ||

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Rural | 25 | 25 | 1.00 | 0.952 |

| Urban | 48 | 47 | ||

| Marks 10th | 80.3±9.47 | 81.1±8.94 | −0.52a | 0.60 |

| Marks 12th | 79.2±9.35 | 80.3±8.28 | −0.71a | 0.48 |

| Father’s education | ||||

| Middle school | 0 | 2 | 12.20 | 0.02 |

| High school | 9 | 4 | ||

| Intermediate | 7 | 15 | ||

| Graduate | 39 | 24 | ||

| Postgraduate | 18 | 27 | ||

| Father’s occupation | ||||

| Skilled worker | 21 | 14 | 5.70 | 0.13 |

| Clerical/shop | 3 | 10 | ||

| Semi professional | 24 | 20 | ||

| Professional | 25 | 28 | ||

| Father’s income (Rs.) | ||||

| 11,000–15,000 | 10 | 13 | 0.57 | 0.75 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 35 | 34 | ||

| >30,000 | 28 | 25 | ||

| Mother’s education | ||||

| Middle school | 3 | 15 | 3.79 | 0.44 |

| High school | 12 | 12 | ||

| Intermediate | 9 | 8 | ||

| Graduate | 25 | 17 | ||

| Postgraduate | 15 | 20 | ||

| Mother’s occupation | ||||

| Unemployed | 68 | 53 | 3.58 | 0.06 |

| Clerical/shop | 3 | 9 | ||

| Professional | 2 | 10 | ||

| Family history of depression | 2 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.28 |

| Family history of suicide | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol use in father | 24 | 12 | 28.5 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use in siblings | 2 | 1 | 3.5 | 0.66 |

| Negative events | 46 | 61 | 1.9 | 0.17 |

Chi-square test. at-test

Medical students had significantly higher concerns about the standards of academic achievement and teaching as compared to the engineering students. Among the 1st year, medical students had significantly higher concerns related to achievement in academic attainment, living and teaching standards than the engineering students. However, this difference was not seen among the students of the 4th year of either stream except for concerns in standards of teaching which were seen to be more among the medical students.

Intragroup analysis of the medical students revealed that 4th year medical students had significantly higher concerns about academic (Z = −3.21, P < 0.01), living (Z = −1.99, P < 0.01), eating (Z = −3.69, P < 0.01), and hostel issues (Z = −2.71, P < 0.01) compared to the 1st year students.

The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among the undergraduates is tabulated in Tables 4-6. Overall, the students in either stream did not differ on scores of SDS, SAS, NDSS, and DAST. The medical students scored higher on both SDS and SAS scales in the senior years than their counterparts in the engineering stream. Intragroup analysis of the medical students showed that the level of anxiety increased significantly among the 4th year medical students than the 1st year [Table 6]. Intragroup analysis of engineering students Table 7 revealed no significant difference in psychological morbidity between the 1st and 4th year.

Table 4.

Prevalence of psychological morbidity among the undergraduates

| Scale | Engineering 1st year (n=73), n (%) | Medical 1st year (n=108), n (%) | Engineering 4th year (n=72), n (%) | Medical 4th year (n=94), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (SDS index) | 23 (31.5) | 29 (26.9) | 20 (27.8) | 34 (36.2) |

| Anxiety (SAS index) | 10 (13.7) | 10 (9.3) | 9 (12.5) | 24 (25.5) |

| Problem drinking (MAST score) | 34 (46.6) | 25 (23.1) | 27 (37.5) | 24 (25.5) |

| Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | 14 (19.2) | 14 (13.0) | 14 (19.4) | 9 (9.6) |

| Problem Drug use (DAST score) | 4 (5.5) | 5 (4.6) | 6 (8.3) | 7 (7.4) |

The values indicate the number of students (and their percentage) scoring above the cut off that delineates possible psychiatric disorder. SDS – Zung’s self-rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self-rating scale for anxiety; MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; NDSS – Nicotine dependence syndrome scale; DAST – Drug abuse screening test

Table 6.

Comparison of psychological morbidity among 1st year versus 4th year medical students

| Scales | t | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (SDS score) | −1.371 | 200 | 0.17 |

| Anxiety (SAS score) | −2.564 | 200 | 0.01 |

| Problem drinking (MAST score) | −0.376 | 200 | 0.71 |

| Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | 0.457 | 200 | 0.65 |

| Problem drug use (DAST score) | 0.510 | 200 | 0.61 |

| Social stress score | −1.78 | 200 | 0.08 |

| RISCI score (stress component) | −9.42 | 200 | <0.01 |

| HESI score (educational stress) | −5.00 | 200 | <0.01 |

SDS – Zung’s self-rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self-rating scale for anxiety; MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; NDSS – Nicotine dependence syndrome scale; DAST – Drug abuse screening test; RISCI – Rhode island stress and coping inventory; HESI – Higher education stress inventory

Table 7.

Comparison of psychological morbidity among 1st year versus 4th year engineering students

| Scales | t | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (SDS score) | 0.545 | 143 | 0.587 |

| Anxiety (SAS score) | 0.427 | 143 | 0.670 |

| Problem drinking (MAST score) | 1.500 | 143 | 0.136 |

| Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | 0.350 | 143 | 0.727 |

| Problem drug use (DAST score) | −1.514 | 143 | 0.132 |

| Social stress score | −3.277 | 143 | 0.001 |

| RISCI score (stress component) | 0.033 | 143 | 0.974 |

| HESI score (educational stress) | 0.547 | 143 | 0.585 |

SDS – Zung’s self-rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self-rating scale for anxiety; MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; NDSS – Nicotine dependence syndrome scale; DAST – Drug abuse screening test; RISCI – Rhode island stress and coping inventory; HESI – Higher education stress inventory

Overall, medical students had significantly higher social (t = −3.1, P < 0.01) and psychological stress (t = −3.3, P < 0.01), but no difference was detected in educational stress (t = −1.4, P > 0.05) [Table 5]. Among the 1st year, medical students had significantly higher social stress (t = −3.3, P < 0.01) than the engineering students, but no difference was detected in the psychological and educational stress. Among the 4th year, the medical students had significantly higher psychological (t = −6.3, P < 0.01) and educational stress (t = −3.7, P < 0.01) than the engineering students, but no difference was noted in the social stress. Furthermore, 4th year medical students had significantly higher perceived psychological stress (t = −9.4, P < 0.01) and educational stress (t = −5.0, P < 0.01) compared to 1st year students [Table 6]. Within the engineering stream, the students scored more on social stress, whereas RISCI stress score and educational stress were not significantly different.

Table 5.

Comparison of psychological morbidity between engineering and medical students

| Scales | t | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (SDS score) | −1.776 | 345 | 0.077 |

| Anxiety (SAS score) | −1.314 | 345 | 0.190 |

| Problem drinking (MAST score) | 2.583 | 345 | 0.010 |

| Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | 2.055 | 345 | 0.041 |

| Problem drug use (DAST score) | −0.967 | 345 | 0.334 |

| Social stress score | −3.259 | 345 | 0.001 |

| RISCI score (stress component) | −3.126 | 345 | 0.002 |

| HESI score (educational stress) | −1.369 | 345 | 0.172 |

SDS – Zung’s self-rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self-rating scale for anxiety; MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; NDSS – Nicotine dependence syndrome scale; DAST – Drug abuse screening test; RISCI – Rhode island stress and coping inventory; HESI – Higher education stress inventory

Correlations were tested among the scores of stress, depression, anxiety, and substance use that revealed that the psychological stress scores [Table 8] correlated positively with the scores on SDS (r = 0.44), SAS (r = 0.51), RISCI (stress component) (r = 0.27), and HESI (r = 0.47). The psychological stress scores correlated negatively with the tobacco use (r = −0.17) and drug use scores (−0.19). Similarly, the educational stress scores also correlated positively with the SDS and SAS scores but not with the substance use scores. Among the 4th year students [Table 9], the psychological stress showed higher positive correlation with the scores on SDS (r = 0.52), SAS (r = 0.59), and higher negative correlation with the MAST (r = −0.26), NDSS (r = −0.24), and DAST scores (r = −0.21). Educational stress also correlated positively with scores of SDS (r = 0.27) and SAS (r = 0.37), but correlation was not significant for substance use scores.

Table 8.

Correlations between stress, psychological morbidity, and substance use in the total sample (n=347)

| Variable | Depression (SDS score) | Anxiety (SAS score) | RISCI score (stress component) | HESI score (educational stress) | Problem drinking (MAST score) | Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | Problem drug use (DAST score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (SDS score) | 1.00 | 0.70** | 0.44** | 0.27** | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety (SAS score) | 0.70** | 1.00 | 0.51** | 0.37** | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| RISCI score (stress component) | 0.44** | 0.51** | 1.00 | 0.47** | −0.10 | −0.17** | −0.19** |

| HESI score (educational stress) | 0.27** | 0.37** | 0.47** | 1.00 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

| Problem drinking (MAST score) | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.10 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.50** | 0.48** |

| Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.17** | −0.01 | 0.50** | 1.00 | 0.43** |

| Problem Drug use (DAST score) | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.19** | 0.07 | 0.48** | 0.43** | 1.00 |

Pearson’s correlation *Significance P<0.05, **Significance P<0.01. SDS – Zung’s self rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self rating scale for anxiety; MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; NDSS – Nicotine dependence syndrome scale; DAST – Drug abuse screening test; RISCI – Rhode island stress and coping inventory; HESI – Higher education stress inventory

Table 9.

Correlations between stress, psychological morbidity and substance use among 4th year students of both streams (n=166)

| Variable | Depression (SDS score) | Anxiety (SAS score) | RISCI score (stress component) | HESI score (educational stress) | Problem drinking (MAST score) | Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | Problem drug use (DAST score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (SDS score) | 1 | 0.76** | 0.52** | 0.27** | −0.22** | −0.09 | −0.08 |

| Anxiety (SAS score) | 0.76** | 1 | 0.59** | 0.37** | −0.25** | −0.08 | −0.08 |

| RISCI score (stress component) | 0.52** | 0.59** | 1 | 0.50** | −0.26** | −0.24** | −0.21** |

| HESI score (educational stress) | 0.27** | 0.37** | 0.50** | 1 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.09 |

| Problem drinking (MAST score) | −0.22** | −0.25** | −0.26** | −0.02 | 1 | 0.61** | 0.55** |

| Tobacco use disorder (NDSS score) | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.24** | −0.01 | 0.61** | 1 | 0.52** |

| Problem drug use (DAST score) | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.21** | 0.09 | 0.55** | 0.52** | 1 |

Pearson’s correlation *Significance P<0.05, **Significance P<0.01. SDS – Zung’s self-rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self rating scale for anxiety; MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; NDSS – Nicotine dependence syndrome scale; DAST – Drug abuse screening test; RISCI – Rhode island stress and coping inventory; HESI – Higher education stress inventory

A linear regression [Table 10] was performed to examine the predictors for alcohol use and the predictor variables used were age, gender, family history of depression or suicide, substance use in the father and scores of psychological stress, educational stress, depression, and anxiety. At the end of model 8, both psychological stress and educational stress were found to be significant predictors of alcohol use.

Table 10.

Linear regression to examine the predictors of alcohol use in the total sample (n=347)

| Model | Coefficientsa | t | Significant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients Beta | |||||

| B | SE | |||||

| 7 | Constant | 4.53 | 3.34 | 1.36 | 0.18 | |

| HESI score | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 3.19 | 0.00 | |

| RISCI score | −0.13 | 0.07 | −0.14 | −1.99 | 0.05 | |

| SDS_score | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.90 | |

| SAS_score | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.11 | −1.42 | 0.16 | |

| Age | −0.09 | 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.57 | 0.57 | |

| Gender | −0.64 | 0.65 | −0.05 | −0.98 | 0.33 | |

| Depr_Fam | −0.09 | 1.05 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.93 | |

| Suicide_Fam | −0.64 | 1.18 | −0.03 | −0.54 | 0.59 | |

| Subsuse_Father | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 1.40 | 0.16 | |

| 8 | (Constant) | 1.45 | 1.03 | 1.40 | 0.16 | |

| HESI score | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 2.88 | <0.01 | |

| RISCI score | −0.18 | 0.06 | −0.19 | −3.10 | <0.01 | |

aDependent variable: MAST scores. Predictor variables – age, gender, family history of depression, family history of suicide, history of substance abuse in father, educational stress (HESI score), psychological stress (RISCI score), depression scores, and anxiety scores, MAST – Michigan alcohol screening test; RISCI – Rhode island stress and coping inventory; HESI – Higher education stress inventory; SDS – Zung’s self-rating scale for depression; SAS – Zung’s self-rating scale for anxiety; SE – Standard error\

DISCUSSION

Demographics

The students in both the engineering and the medical streams were similar with respect to the age gender, urbanicity, socioeconomic status, however, differed slightly in the education of the parents which was higher in the medical cohort. Furthermore, the medical students had scored more at the board examinations in the 11th and 12th standards. The demographic questionnaire also enquired about recent negative events in the form of recent loss of a family member, friend or failures at school that were not found to be significantly different between the four groups.

Psychiatric morbidity

A large number of studies have found the prevalence of depression ranging from 8.7% to 71.3% among medical students.[10] Our study found that 30.5% students suffered from depression (SDS index score >40) [Table 3]. Among the medical students, more number of 4th year students (36.2%) was depressed than the 1st year (26.9%); however, the findings were not statistically significant. No gender or familial differences were found. A number of studies have found anxiety levels in the medical students to be higher than the general population.[25,26] The present study found that almost 15.3% students had significant levels of anxiety (SAS score >45) [Table 3]. Fourth-year medical students had a significantly higher level of anxiety than the 1st year.

Studies have found that a significant number of students use alcohol, with the prevalence ranging from 19.13%[18] to 41.46%[27] and 0%–17% use tobacco.[16] The most common illicit drug being used was cannabis[16] (4%–11.8%). Our study noted that the prevalence of “problem drinking” was around 31.7%, whereas 14.4% used tobacco and 6.3% used some drug in the college, the most common being recreational use of cannabis [Table 3]. These figures are comparative to those published in other studies. The substance use was significantly less among the females with only 9/45 females among the medical students admitting to substance use (alcohol – 5, tobacco – 2, drugs [cannabis] – 2). The engineering students had a significantly higher use of alcohol than medical students (that may be attributed to genetic influence and parental modeling). Among the medical students, substance use was not significantly different.

Stress and coping

A more nuanced interpretation of stress among students was measured using the various scales and questionnaires. First were about the different concerns of the students regarding their expectations from the college and the reality. These concerns ranged from academic to financial concerns, concerns about the family, hostel, living and eating standards in the hostel and were measured on a Likert scale. Second, psychological stress and coping were measured by the RISCI scale, and third, stress specific to higher education was measured using the HESI. Among medical students, the concerns about finances, difficulty in studying, unsupportive learning environment, work load, and time management challenges have been found to impact the students and have been brought out as major stressors apart from the educational stress with higher levels of dysfunctional coping.[28,29,30,31,32] In the current study, medical students had major concerns related to academics and teaching standards that gave way to psychological and educational stress by the 4th year indicating the way priorities change over the course of the curriculum. Furthermore, within the same course, medical students accumulated stress over the period of 4 years that led to dysfunctional coping in the form of overt psychopathology [Table 6]. Furthermore, 4th year students had more dysfunctional coping (Z = −2.25, P < 0.05) than the 1st year. On the other hand, among engineering students, 1st year perceived more psychological stress (RISCI stress score); however, other variables did not differ. On measures of coping, it was noted that the medical and engineering students did not differ. The important derivation from the above findings is that medical students are indeed stressed out. The levels of stress are significant in the final years of college and are much more than observed in the other technical college.

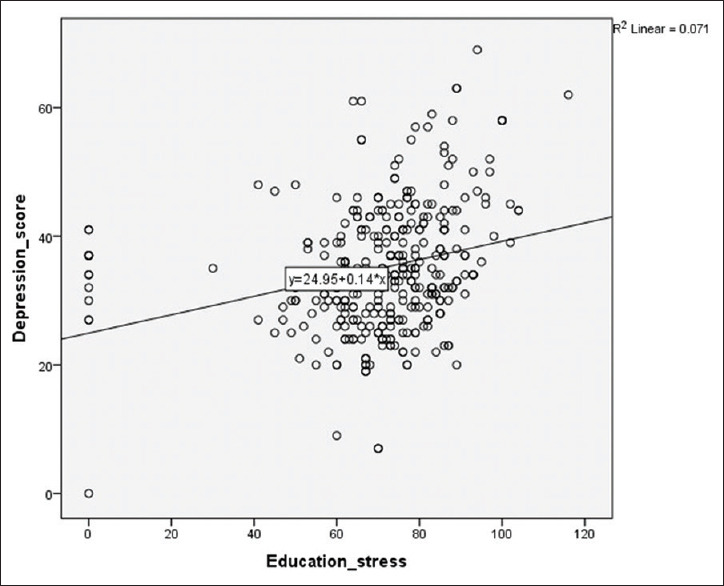

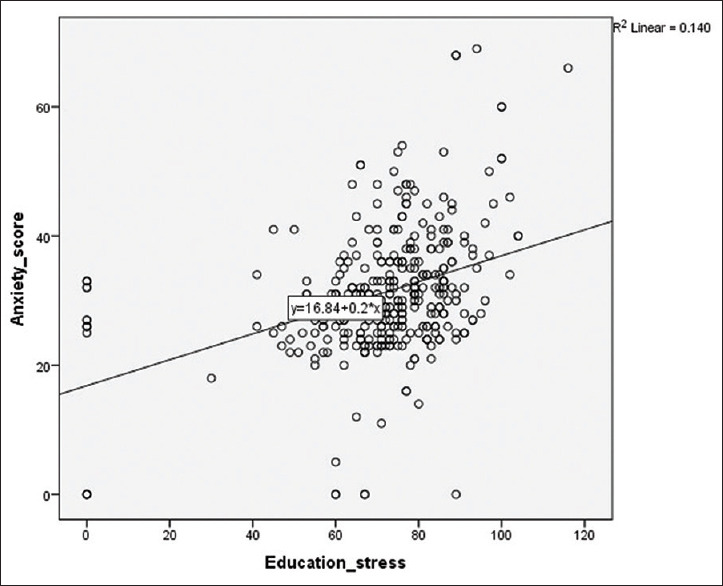

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were generated to examine the relationship between stress, psychopathology, and substance use. As was expected, stress, both psychological and educational was found to be positively correlated with depression [Figure 1] and anxiety [Figure 2]. The surprising finding was that stress correlated negatively with the substance use scores. This may be explained by the fact that substance users do experience a temporary well-being that may be associated with drug use. A similar picture was noted when correlations were tested within the medical students cohort. Since educational stress was not associated with substance use, perhaps, substance use takes a different pathway through increased psychological stress that may involve relationships with peers, family and teachers and other concerns. The linear regression examined the predictors of alcohol use from a host of factors. At the end of the model, two factors remained significant, psychological and educational stress. The two have been examined separately based on different scales that have been used; however, there may be a lot of overlap between the two.

Figure 1.

Graph showing correlation between educational stress and depression scores

Figure 2.

Graph showing correlation between educational stress and anxiety scores

The findings of the study confirm that the psychological morbidity and educational stress is much more common among medical students, and it is higher than in engineering students. Furthermore, the psychological morbidity and educational stress are higher among final year students than 1st year. This psychological morbidity leads to dysfunctional coping with temporary alleviation in stress perception with the use of substances which could later vitiate the cycle of increasing morbidity.

The strength of the study was in the sample size (347) and the comparison of medical students with students of another professional college. The main limitation of the study was that, being a cross-sectional study, it could only get a snapshot of the psychological stress and morbidity among the undergraduates. Furthermore, in the absence of a clinical interview by a mental health professional, the scores of depression and anxiety indicate possible psychological morbidity but do not confirm the diagnosis. Early childhood adversity and temperamental factors have not been included in the study that may be major confounding variables. Furthermore, it has been presumed that the environment may be similar in the two colleges which may be a major limiting factor. A follow-up of these students when they graduate from medical school may help in assessing the impact of educational stress on their psychological health in the long term.

CONCLUSION

A number of studies have been conducted in the last few decades that showed that medical students do have high educational stress and psychological morbidity. The peculiarity of the present study is that it not only evaluated stress and morbidity among the medical students, but it also compared it with students in a similar scenario except the differences in kind of education imparted and the socio-developmental trajectories therein. The study confirms the fact that medical students have higher levels of educational stress which is associated with psychological morbidity and substance abuse. Psychoactive substances were possibly being used as a measure to alleviate psychological stress which is again a form of dysfunctional coping. In light of the above results, the current mental health scenario needs a relook at the stress busting interventions in place. There is an urgent need for revision in existing protocols within medical schools to periodically evaluate mental health status along with targeted activities to reduce psychiatric morbidity through primary and secondary prevention that may go a long way in alleviating stress among the healers of the society.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chew-Graham CA, Rogers A, Yassin N. I wouldn’t want it on my CV or their records: Medical students’ experiences of help-seeking for mental health problems. Med Educ. 2003;37:873–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sreeramareddy CT, Shankar PR, Binu VS, Mukhopadhyay C, Ray B, Menezes RG. Psychological morbidity, sources of stress and coping strategies among undergraduate medical students of Nepal. BMC Med. 7 doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-26. Educ 200726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39:594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johari AB, Hashim IN. Stress and coping strategies among medical students in National University of Malaysia, Malaysia University of Sabah and University Kuala Lumpur Royal College of Medicine Perak. J Community Health. 2009;15:106–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusoff MS, Liew YY, Ling HW, Tan CS, Loke HM, Lim XB, et al. A study on stress, stressors and coping strategies among Malaysian medical students. Int J Stud Res. 2011;1:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaid ZA, Chan SC, Ho JJ. Emotional disorders among medical students in a Malaysian private medical school. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:895–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aktekin M, Karaman T, Senol YY, Erdem S, Erengin H, Akaydin M. Anxiety, depression and stressful life events among medical students: A prospective study in Antalya, Turkey. Med Educ. 2001;35:12–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko SM, Kua EH, Fones CS. Stress and the undergraduate. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:627–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314:2373–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar S, Gupta R, Menon V. A systematic review of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students in India. J Ment Health Hum Behav. 2017;22:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kundapur R, Shetty SM, Kempaller VJ, Kumar A, Anurupa M. Violence against Educated women by intimate partners in urban Karnataka, India. Indian J Community Med. 2017;42:147–50. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_41_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satheesh BC, Prithviraj R, Prakasam PS. A study of perceived stress among undergraduate medical students of a Private Medical College in Tamil Nadu. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4:994–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah M, Hasan S, Malik S, Sreeramareddy CT. Perceived stress, sources and severity of stress among medical undergraduates in a Pakistani medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saipanish R. Stress among medical students in a Thai Medical School. Med Teach. 2003;25:502–6. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000136716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supe AN. A study of stress in medical students at Seth GS Medical College. J Postgrad Med. 1998;44:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roncero C, Egido A, Rodríguez-Cintas L, Pérez-Pazos J, Collazos F, Casas M. Substance use among medical students: A literature review 1988-2013. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2015;43:109–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayala EE, Roseman D, Winseman JS, Mason HR. Prevalence, perceptions, and consequences of substance use in medical students. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1392824. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1392824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora A, Kannan S, Gowri S, Choudhary S, Sudarasanan S, Khosla PP. Substance abuse amongst the medical graduate students in a developing country. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143:101–3. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.178617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zung WW. A self-reported scale for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fava JL, Ruggiero L, Grimley DM. The development and structural confirmation of the Rhode Island stress and coping inventory. J Behav Med. 1998;21:601–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1018752813896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selzer ML. The Michigan alcoholism screening test (MAST): The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickcox M. The nicotine dependence syndrome scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:327–48. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gavin DR, Ross HE, Skinner HA. Diagnostic validity of the drug abuse screening test in the assessment of DSM-III drug disorders. Br J Addict. 1989;84:301–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassi R, Sharma S, Kaur M. A study of correlation of anxiety levels with body mass index in new MBBS students. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;4:208–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shete A, Garkal K. A study of stress, anxiety, and depression among postgraduate medical students. CHRISMED J Health Res. 2015;2:119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garg A, Chavan BS, Singh GP, Bansal E. Patterns of alcohol consumption in medical students. J Indian Med Assoc. 2009;107:151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aamir IS. Stress level comparison of medical and nonmedical students: A cross sectional study done at various professional colleges in Karachi, Pakistan. Acta Psychopathol. 2017;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg K, Agarwal M, Dalal PK. Stress among medical students: A cross-sectional study from a North Indian Medical University. Indian J Psychiatry. 20W1;;59:2017–8. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_239_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinen I, Bullinger M, Kocalevent RD. Perceived stress in first year medical students – Associations with personal resources and emotional distress. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill MR, Goicochea S, Merlo LJ. In their own words: Stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med Educ Online. 2018;23:1530558. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1530558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balaji NK, Murthy PS, Kumar DN, Chaudhury S. Perceived stress, anxiety, and coping states in medical and engineering students during examinations. Ind Psychiatry J. 2019;28:86–97. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_70_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]