Abstract

Dietary restriction (DR) increases life span and improves health in most model systems tested, including non-human primates. In C. elegans, as in other models, DR leads to reprogramming of metabolism, improvements in mitochondrial health, large changes in expression of cytoprotective genes and better proteostasis. Understandably, multiple global transcriptional regulators like transcription factors FOXO/DAF-16, FOXA/PHA-4, HSF1/HSF-1 and NRF2/SKN-1 are important for DR longevity. Considering the wide-ranging effects of p53 on organismal biology, we asked whether the C. elegans ortholog, CEP-1 is required for DR-mediated longevity assurance. We employed the widely-used TJ1 strain of cep-1(gk138). We show that cep-1(gk138) suppresses the life span extension of two genetic paradigms of DR, but two non-genetic modes of DR remain unaffected in this strain. We find that two aspects of DR, increased autophagy and up-regulation of the expression of cytoprotective xenobiotic detoxification program (cXDP) genes, are dampened in cep-1(gk138). Importantly, we find that background mutation(s) in the strain may be the actual cause for the phenotypic differences that we observed and cep-1 may not be directly involved in genetic DR-mediated longevity assurance in worms. Identifying these mutation(s) may reveal a novel regulator of longevity required specifically by genetic modes of DR.

Introduction

Dietary restriction (DR) extends longevity and imparts health benefits to a wide range of metazoans. Research over the past decades, using Caenorhabditis elegans, has revealed the role of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors like FOXA/PHA-4 [1–4], NRF2/SKN-1 [5], HIF1/HIF-1 [6], TFEB/HLH-30 [7], HNF4/NHR-49 [2], HSF1/HSF-1 [8] and FOXO/DAF-16 [9] in the regulation of the transcriptional landscape required to ensure long life span of DR animals. The mechanisms by which DR affects life span are diverse and depends on the mode of implementation. In C. elegans, DR may be implemented by genetic means as well as through non-genetic dietary interventions. For example, the eat-2 mutants that have defective pharyngeal pumping is considered the classical genetic models of DR [10]. We have recently shown that knocking down a serine-threonine kinase gene drl-1 using RNAi leads to a DR-like phenotype that extends life and health span [2]. Non-genetically, DR can be implemented by diluting bacteria in liquid media [1, 5] or on solid media plates [9, 11], by peptone restriction [12], by feeding a non-hydrolysable glucose analog [13] or even by complete depletion of bacterial feed [14]. Interestingly but quite expectedly, the transcription factor requirements also vary with the model of DR. For example, the key transcription factor required in DR regime on solid plates is DAF-16 while for eat-2 mutants, drl-1 KD worms and for bacterial dilution in liquid, PHA-4 is required [1, 2, 9]. On the other hand, a DR regime in liquid media on solid support requires SKN-1 [5] while increased life span on complete removal of food is dependent on HSF-1 [14]. These observations point to the complex modalities of gene regulation brought about by nutrient signalling and DR implemented by various regimes that still need to be elucidated, including identifying new transcriptional regulators.

The p53 protein is a well-known tumour suppressor that has an important role in maintaining genome integrity by inducing DNA repair, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to genotoxic stress [15]. Various model organisms like mice [16, 17], flies [18, 19] and worms [20, 21] have been exploited to investigate the role of p53 in the aging process. In C. elegans, CEP-1 is the functional ortholog of p53. Interestingly, knocking down cep-1 by mutation or RNAi leads to a small but significant increase in life span, in a context dependent manner [20, 21]. The cep-1(gk138) allele has been widely used in studies on cep-1. The TJ1 strain was prepared by backcrossing cep-1(gk138) ten times with wild-type N2 [21] and is available from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC). In this study, we asked whether TJ1 cep-1(gk138) produced life span extension when grown under different DR regimes. We found that the genetic modes of DR, namely drl-1 KD and eat-2 mutant, failed to extend life span in TJ1. However, non-genetic DR regimes, namely BDR and 2-DOG were unaffected. We show that under genetic DR, two important cellular processes, autophagy induction and cytoprotective response, through the activation of the xenobiotic detoxification program (cXDP) gene expression, fail to get upregulated in TJ1 cep-1(gk138). Also, TJ1 differentially affects the two genetic models of DR in terms of regulation of fat storage. However, we found that after backcrossing the TJ1 allele 2 times, or on using two other mutant alleles, life span extension on drl-1 RNAi became independent of the absence of cep-1, suggesting that background mutation(s) in the TJ1 strain may suppress genetic DR-mediated longevity extension. Interestingly, cep-1(gk138) TJ1 as well as the 12X backcrossed mutant consistently enhanced dauer formation in the insulin signalling defective daf-2(e1370), suggesting that it may be a bona fide property of cep-1. Since TJ1 differentially influences the two genetic models of DR, it will be interesting to identify the background mutation(s).

Results

Cep-1(gk138) (TJ1) suppresses life span of genetic paradigms of DR

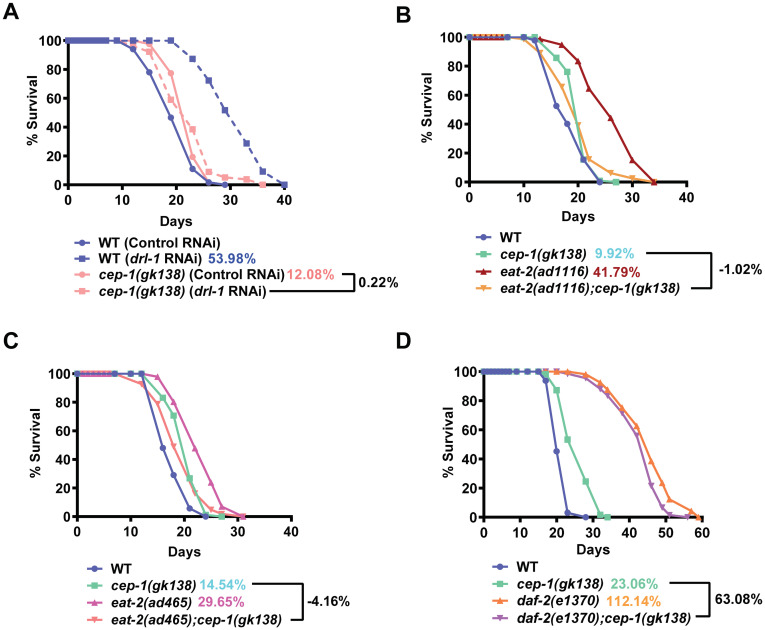

The gk138 allele (TJ1; 10x backcrossed) was obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) and has a 1660 bp deletion in the cep-1 gene. In our lab, we are characterizing a genetic model of DR where knocking drl-1 kinase gene leads to a DR-like phenotype, resulting in a dramatic increase in life span [2]. We found that drl-1 KD worms failed to show life span extension in TJ1 cep-1(gk138) (Fig 1A) [to be called cep-1(gk138)]. The eat-2 mutants represent the classical genetic models of DR [10]. We compared the life span of eat-2(ad1116) with the long-lived eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138) and found that the life span of the former is completely suppressed (Fig 1B). Similar results were observed with another allele, the eat-2(ad465) (Fig 1C). Together, we found that TJ1 cep-1(gk138) mutant suppresses life spans of two genetic paradigms of DR, the eat-2 mutants as well as the worms grown on drl-1 RNAi.

Fig 1. In cep-1(gk138), genetic paradigms of Dietary Restriction fail to extend life span.

(A) The life span extension upon drl-1 KD in WT is suppressed when cep-1(gk138) is used. (B) The extended life span of eat-2(ad1116) is supressed in eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138). (C) The extended life span of eat-2(ad465) is supressed in eat-2(ad465);cep-1(gk138). (D) The life span of daf-2(e1370) is partially suppressed when combined with cep-1(gk138), as in daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138). Life spans were performed at 20 °C. Details of life span are provided in S1 Table. Mantel-Cox log rank test using OASIS software available at http://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis [22] was used for statistical analysis. Life spans in 1B and 2B have identical controls as they were part of the same experiment (also see S1 Fig).

We next asked whether other longevity pathways are influenced by cep-1(gk138). We analysed the effect on the long life span of the reduced Insulin/IGF-1 signalling (IIS) mutant, daf-2(e1370). The daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138) showed a partial reduction compared to the life span of daf-2(e1370) (Fig 1D), showing that the effect was more robust in case of DR. Interestingly however, the dauer formation of daf-2(e1370) was dramatically enhanced in daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138) (S1 Fig). This shows that life span and dauer development is differentially regulated in the IIS pathway mutant in combination with TJ1 cep-1(gk138).

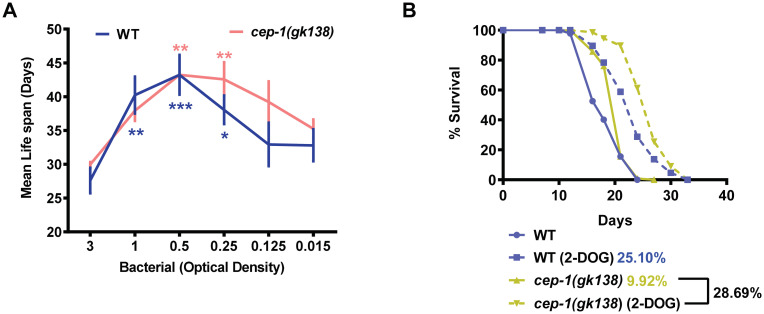

DR may be initiated non-genetically in worms either by diluting the bacterial feed (BDR) [1] or by using a non-hydrolysable glucose analog, 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG) [13]. We asked if the cep-1(gk138) disrupts the life span extension of the non-genetic paradigms of DR as well. We observed that bacterial dilution also generated the typical bell-shaped curve in the BDR assay of cep-1(gk138), as seen in WT worms, when average life spans were plotted against the bacterial dilutions (Fig 2A). Likewise, on supplementation of 2-DOG, cep-1(gk138) showed life span extension similar to WT worms (Fig 2B). Overall, both the non-genetic DR paradigms in TJ1 cep-1(gk138) could increase life span, indicating that it only affects the genetic modes of DR.

Fig 2. The life span extension on non-genetic modes of DR remain unaffected in cep-1(gk138).

(A) A bell-shaped curve is observed when WT or cep-1(gk138) worms are grown on different dilutions of bacterial feed and the average life span plotted against the OD600. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N = 3 independent experiments. Two-way Annova was used for statistical analysis. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001. (B) Supplementation of 2-DOG extends life span in cep-1(gk138) mutant similar to WT. Life span were performed at 20°C and details are provided in S1 Table. Mantel-Cox log rank test using OASIS software available at http://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis [22] was used for statistical analysis.

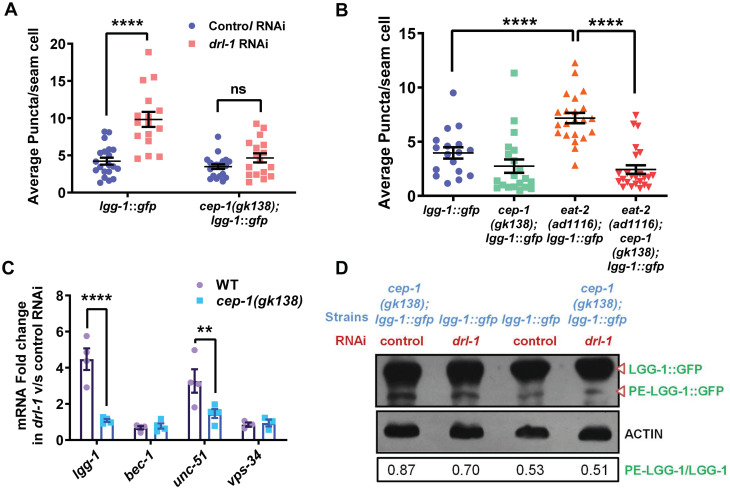

Autophagy fails to be upregulated in cep-1(gk318) (TJ1) undergoing DR

A prominent marker for long-lived mutants is increased autophagy. DR-induced autophagy requires the transcription factors FOXA/PHA-4 and HLH-30, implying that autophagy is transcriptionally regulated during DR [7, 23]. We asked whether autophagy is mis-regulated in the TJ1 cep-1(gk138) undergoing the genetic paradigms of DR, providing a possible reason for life span suppression. We observed that the increase in autophagosome number, as determined by the number of puncta in the seam cells of the L3 stage lgg-1::gfp transgenic worms, after knocking down drl-1 in WT background, was completely suppressed in cep-1(gk138) (Fig 3A, S2A Fig). Next, we found that the increased puncta in eat-2(ad1116);lgg-1::gfp was also suppressed in eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138);lgg-1::gfp (Fig 3B, S2B Fig). Basal levels of autophagy were unchanged in cep-1(gk138), compared to WT. This implies that cep-1(gk138) influences autophagy in the two genetic models of DR.

Fig 3. Cep-1(gk138) regulates autophagy during DR.

(A) Increased autophagosome formation in lgg-1::gfp grown on drl-1 RNAi is suppressed in cep-1(gk138); lgg-1::gfp. Quantification of GFP puncta for one of three independent experiments is shown. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. No. of animals analysed, n≥16. Two-way Annova with Sidak’s multiple comparison tests was used for statistical analysis. ****P≤0.0001, ns = non-significant. (B) The increased autophagosome formation in eat-2(ad1116) is suppressed in eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138). Quantification of GFP puncta for one of three independent experiments is shown. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. No. of animals analysed, n≥17. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was used for statistical analysis. ****P≤0.0001. Source data is provided in S1 File. (C) Transcript levels of autophagy genes, lgg-1, bec- 1, unc-51, vps-34 in WT and cep-1(gk138) on control and drl-1 RNAi. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N≥3 independent experiments. Two-way Annova with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. **P≤0.01, ****P≤0.0001. (D) Western blot using anti-GFP antibody to detect the unmodified LGG-1 or PE-LGG-1. The lgg-1::gfp or cep-1(gk138);lgg-1::gfp worms were grown on control or drl-1 RNAi. Densitometric quantification of protein bands were performed using ImageJ and ratio of PE-LGG-1/LGG-1 is shown. β-ACTIN was used as a loading control. One representative blot out of the two independent experiments is shown. Experiments were performed at 20 °C. Uncropped blots are provided in S1 File (also see S2 Fig).

We next followed up this observation by determining the expression levels of four of the important autophagy genes (lgg-1, bec-1, vps-34, and unc-54) under control and drl-1 KD conditions, using wild-type and cep-1(gk138). We observed a transcriptional up-regulation of lgg-1 and vps-34 on knock-down of drl-1 as compared to control RNAi, and this increase was reduced in cep-1(gk138) (Fig 3C). To biochemically determine the level of autophagy up-regulation, the extent of PE-LGG-1 formation was evaluated using western blot analysis. We observed that on drl-1 KD, there was an increase in the PE-LGG-1 band intensity, corresponding to the increased autophagosome numbers seen in the puncta assay. In line with the autophagosome assay, the PE- LGG-1 band intensity reduced in cep-1(gk138) as compared to wild-type on drl-1 KD (Fig 3D).

In order to find whether the regulation of autophagy in cep-1(gk138) was specific to the modes of DR used in this study, we determined whether autophagy induction in daf-2(e1370) is also influenced by the TJ1 cep-1(gk138). In agreement with previous data [24], we also found that reduced IIS led to increased autophagic puncta. However, this increase was maintained in the cep-1(gk138) background (S2C–S2E Fig). These observations show that TJ1 cep-1(gk138) regulates autophagy in response to genetic modes of DR, but not on lowering IIS signalling.

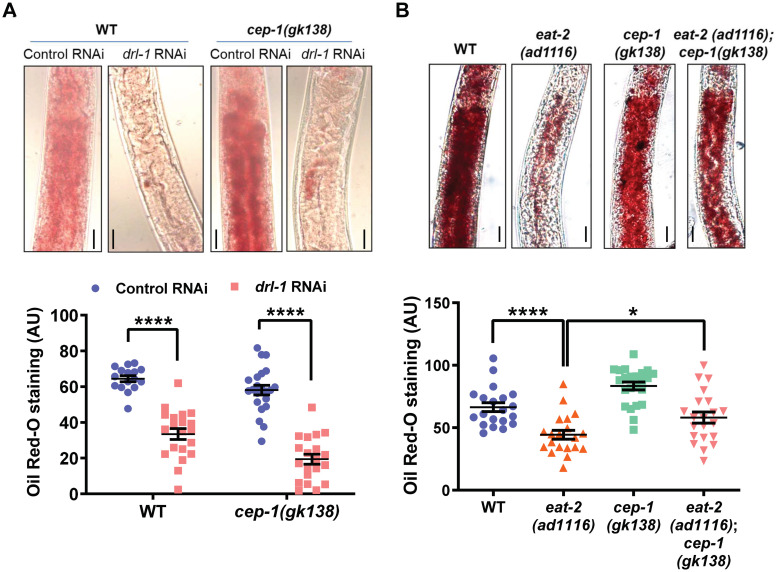

Fat storage is differentially affected in the two genetic DR models by cep-1(gk138)

One of the hallmarks of DR is metabolic reprogramming towards increased fatty acid oxidation that leads to depletion of stored fat [2]. We asked whether cep-1(gk138) would have differences in depletion of stored fat in the two genetic models of DR. We found that on drl-1 KD in both WT and TJ1 cep-1(gk138), fats stores were depleted, as measured by Oil Red O staining of fixed worms (Fig 4A). Surprisingly, in the eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138), the reduced fat stores of eat-2(ad1116) was partially restored (Fig 4B). Similar observations were made for eat-2(ad465);cep-1(gk138) (S3 Fig). Together, TJ1 cep-1(gk138) responds differently to the two genetic modes of DR.

Fig 4. Fat storage is differentially regulated by cep-1(gk138).

(A) Oil Red O staining of WT or cep-1(gk138) grown on control or drl-1 RNAi. Lowering of fat storage takes place in both the strains grown on drl-1 RNAi. Representative images (upper panel) and quantification (lower panel) for one of three independent experiments is shown. Images were captured at 400X magnification. Scale bar is 20 μm. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. No. of animals analysed, n≥16. Two-way Annova with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. ****P≤0.0001. (B) Oil Red O staining of eat-2(ad1116) or eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138). Lowering of fat storage in eat-2(ad1116) is attenuated in eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138). Representative images (upper panel) and quantification (lower panel) for one of three independent experiments is shown. Images were captured at 400X magnification. Scale bar is 20 μm. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. No. of animals analysed, n≥20. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was used for statistical analysis. ****P≤0.0001, *P≤0.05. Experiments were performed at 20 °C. Representative images presented in Fig 4B and S3 Fig are from the same experiment and thus, have the same control panels. Source data is provided in S1 File (also see S3 Fig).

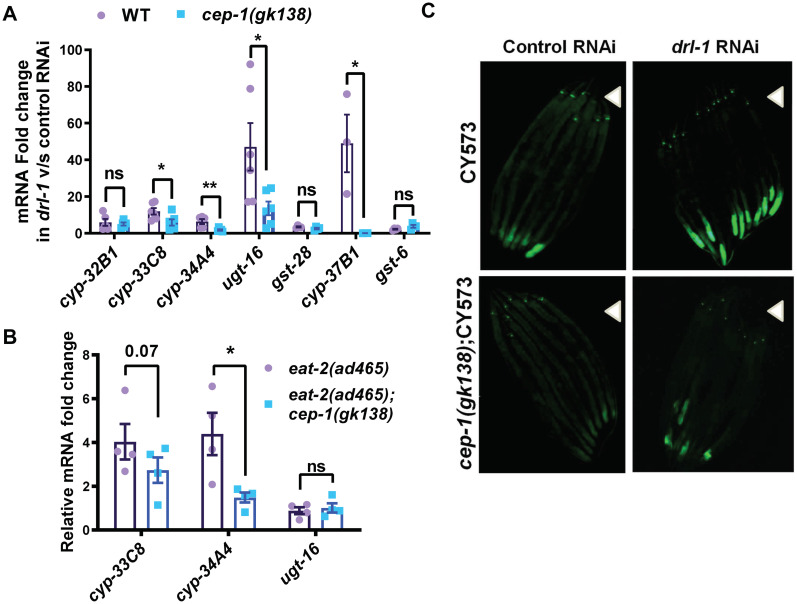

Suppression of cytoprotective gene activation in cep-1(gk138) undergoing genetic DR

Previous study from our lab has shown that drl-1 KD leads to upregulation of the cytoprotective xenobiotic detoxification pathway (cXDP) genes to ensure DR-mediated life span enhancement [2]. This up-regulation requires the conserved transcription factors like PHA-4, NHR-8 and AHR-1. Since CEP-1 is also known to regulate detoxification genes like gst-4 [25], we asked whether the cXDP genes are optimally upregulated in TJ1 cep-1(gk138) undergoing genetic modes of DR. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that the phase I and phase II cXDP were up-regulated in wild-type on drl-1 KD. However, the extent of upregulation of some of these genes, like cyp-33, cyp-35, cyp-37 and ugt-16 was significantly reduced in cep-1(gk138) grown on drl-1 RNAi. Other genes, like cyp-32 and gst-28 were downregulated but not significantly (Fig 5A). The transcript levels of three of these genes were also determined in eat-2 mutant and two were found to be reduced in the TJ1 background (Fig 5B).

Fig 5. The increased expression of cXDP genes in cep-1(gk138), undergoing genetic DR, is partially attenuated.

(A) The mRNA levels of cXDP genes are increased in WT grown on drl-1 RNAi, but partially suppressed in cep-1(gk138). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N≥3 independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ns = not significant. (B) The increased levels of cXDP genes in eat-2(ad465) is reduced in eat-2(ad465);cep-1(gk138). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N≥3 independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical anaysis. *P≤0.05, ns = not significant. (C) Representative images of one of two independent experiments, showing increase in pcyp-35B1:gfp expression on drl-1 KD in WT, which abrogated in cep-1(gk138). n≥20. Multiple overlapping images were captured at 100X to cover the length of whole worm and then stitched together to generate a contiguous image. Arrow heads point towards the head of the worms. Experiments were performed at 20 °C.

We also used the transcriptional reporter-containing transgenic strain, Pcyp- 35B1::gfp that has the promoter of Cyp-35B1, a gene of phase I XDP, driving the expression of GFP in the intestine. When drl-1 is knocked down in Pcyp-35b1::gfp, the expression of GFP increases but this was suppressed in cep-1(gk138);Pcyp35b1::gfp (Fig 5C). Together, these results show that the optimal expression of cXDP genes during DR is hampered in TJ1 cep-1(gk138).

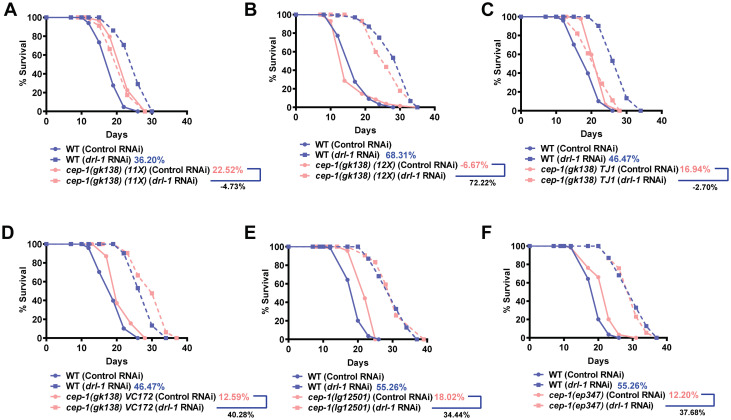

Background mutation(s) in TJ1 cep-1(gk138) may be responsible for suppressing DR life span

The TJ1 strain obtained from CGC is 10x backcrossed. We observed that while the original 10x (Fig 1A) as well as the 11x backcrossed [the CGC TJ1 cep-1(gk138) backcrossed once] strains showed complete suppression of life span when grown on drl-1 RNAi (Fig 6A), the 12X strain [the CGC TJ1 cep-1(gk138) backcrossed twice] failed to do so (Fig 6B). We reordered the stains from CGC along with VC172 that is 0X backcrossed. We found that the newly acquired TJ1 strain still led to complete suppression of drl-1 RNAi life span extension (Fig 6C) while similar observation was not seen with the VC172 (Fig 6D). Further, we tested two other alleles of cep-1, namely cep-1(ep347) and cep-1(lg12501) as well as another 12X backcrossed line generated earlier [20] and found that life span was not suppressed as before (Fig 6E and 6F, S4A Fig). Together, we believe that a background mutation(s) in the 10X TJ1 strain of cep-1(gk138) suppresses the positive effects of the two different genetic modes of DR. Interestingly though, the dauer enhancement phenotype of daf-2(e1370) is still retained in the daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138)(12X) (S4B Fig), suggesting either that this phenotype is specific to cep-1 or that the mutation is closely linked to daf-2 locus. Future studies to characterize and identifying the mutation(s) may lead to finding novel regulators of DR life span.

Fig 6. Background mutation(s) in cep-1(gk138) may be responsible for suppressing life span of genetic paradigms of DR.

(A) Life span analysis of TJ1 cep-1(gk138) 11X backcrossed strain, (B) 12X backcrossed strain, (C) TJ1 strain reordered from CGC, (D) VC172 cep-1(gk138) 0X backcrossed strain, (E) cep-1(lg12501) and (F) cep-1(ep347) along with WT, grown on control or drl-1 RNAi. Life span was performed at 20°C and details are provided in S1 Table. Mantel-Cox log rank test using OASIS software available at http://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis [22] was used for statistical analysis. Life spans in Fig 6C-6D and 6E-6F have identical controls as they were part of the same experiment (also see S4 Fig).

Discussion

P53 is a multi-functional transcription factor that directs the regulation of various biological processes such as DNA repair, apoptosis, cellular senescence and autophagy in response to diverse stresses like DNA damage, oxidative stress, and nutrient deprivation. P53 regulates aging in a wide range of species, ranging from flies, worms, mice and humans [26]. As a guardian of the genome, it protects against malignancy, but this tumour suppressor activity comes as a trade-off to accelerated aging. Transgenic mice overexpressing p44, the short isoform of p53 shows reduced incidences of cancer, but with premature aging phenotypes [17]. On the other hand, the “super p53” mice model with constitutively activate p53 has lesser risk of cancer but shows no longevity benefits [27]. In Drosophila melanogaster (Dm), reduction of Dmp53 activity by expressing the dominant negative (DN) form of p53 in insulin producing cells (IPCs), a subset of neurons (equivalent to mammalian pancreatic beta- cells) leads to lower levels of dILP2 mRNA as well as reduced IIS pathway in fat body and thus, extends life span [19]. Life span extension by DN-Dmp53 also requires 4E-BP, a downstream component of mTOR pathway [18]. Interestingly, p53 exhibits the phenomenon of antagonistic pleiotropy in a development stage-specific and sex-specific manner. It favours survival at younger stages by acting as a tumour suppressor while it promotes cellular senescence at later stages of life, limiting survival [28]. A delicate balance in the activation status of p53 and a threshold of stress may determine the transition from favourable to detrimental effects on longevity. In addition, flies expressing DN-p53 do not show further life span extension either by calorie restriction or by over-expressing dSir2, suggesting the involvement of p53 in the calorie restriction pathway [29].

Knocking down the C. elegans ortholog of p53, cep-1 leads to increased life span in a DAF-16/FOXO-dependent manner [21]. The extended life span of cep-1(gk138) mutant is dependent on the autophagy gene, bec-1 [30]. In addition, cep-1 inactivation in the mitochondrial ETC mutants shortens the life span of the long-lived isp-1 mutant exhibiting severe mitochondrial stress while extending life span in response to mild stress, as in the short-lived mev-1 mutant [20].

In this study, we investigated the role of the C. elegans ortholog of p53, cep-1, in DR-mediated longevity assurance. We employed the commonly-used allele, TJ1 cep-1(gk138) that is 10X backcrossed and available from CGC. Although we found that the strain prevented genetic modes of DR from increasing life span, the effect may be the result of background mutation(s). The TJ1 strain has been widely used to study the role of cep-1 in aging in C. elegans. The TJ1 strain has a significantly enhanced life span [21] and the increased life span was dependent on functional autophagy [31]. Ventura et al., also used TJ1 to show that cep-1 mediates the life span effects of the mitochondrial mutants, depending on the mitochondrial bioenergetic stress [32]. In the TJ1 strain, mild genetic mitochondrial perturbations that are known to increase life span failed to do so. Additionally, the life span shortening effects of severe mitochondrial disruption also required cep-1 [32]. The TJ1 strain was also used in a later study which further characterized the opposing effects of cep-1 on life span of mitochondrial mutants [20]. However, in that study the TJ1 strain was backcrossed two times with wild-type.

P53 is a complex biological molecule that has both pro- as well as anti-aging properties that depend on the physiological context [33]. It is the dominant tumour suppressor that facilitates DNA repair by halting cell cycle. It also directly impacts the activity of DNA repair systems [34]. Understandably, loss of p53 would lead to accumulation of mutations in the DNA. The TJ1 cep-1(gk138) allele may have accumulated unlinked mutations due to the absence of the p53 ortholog. As a result, the strain may show additional phenotypes that are not linked to cep-1. Although Drosophila studies indicate that DmP53 may increase life span in a manner similar to caloric restriction [18, 29], our study in C. elegans suggests that it may be due to background mutation(s). Considering our results, the role of p53 in DR may not have evolved in C. elegans or other nematodes. In future, one has to carefully design experiments to decouple the role of background mutation(s) in the highly mutable strain lacking p53, to decipher the real biological function of this important transcription factor on longevity. It will be prudent to experiment with additionally backcrossed TJ1 as well as validating the outcomes parallelly in other alleles like cep-1(lg12501) and cep-1(ep347).

Experimental procedures

Strains

All the strains were maintained at 20°C, unless otherwise stated, on a lawn of E. coli (OP50) bacteria seeded on standard Nematode Growth Media (NGM) plates [35]. The E. coli bacteria were grown overnight in Luria Bertani (LB) media at 37 °C, and 200 or 1000 μl of the culture was seeded on 60 or 90 mm NGM agar plates, respectively. The plates were set at room temperature for 2–3 days to allow the bacteria to grow.

Strains used in the study are

N2 Bristol as wild-type, TJ1 cep-1(gk138) I, eat- 2(ad1116) II, eat-2(ad465) II, daf-2(e1370) II, adIs2122 [lgg-1p::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6(su1006)], CY573-bvIs5 [cyp-35B1p::GFP + gcy-7p::GFP], XY1054 cep-1(lg12501) I, VC172 cep-1(gk138) I, CE1255 cep-1(ep347).

Double mutants generated in the study are

eat-2(ad1116);cep-1(gk138),eat-2(ad465); cep-1(gk138), daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138), cep-1(gk138);adIs2122, eat-(ad1116); cep-1(gk138);adIs2122, eat-(ad1116);adIs2122, daf-2(e1370); cep-1(gk138);adIs2122, daf-2(e1370);adIs2122, cep-1(gk138);bvIs5 [named cep-1(gk138);CY573].

Preparation of RNAi plates

Nematode Growth Media (NGM) was supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 2 mM IPTG to prepare RNAi plates. E. coli HT115 was transformed with the L4440 plasmid or drl-1 cloned in L4440 plasmid. A single colony of bacteria was grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth containing 100 μg/ml Ampicillin and 12.5 μg/ml Tetracycline, overnight at 37°C in a shaker incubator. Next day, this culture was used as primary inoculum for sub-culturing in a fresh batch of LB media containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin at a ratio of 1:100 and grown until OD600 reached 0.6 at 37°C. The bacterial cells were then harvested at 5000 rpm, 4°C and resuspended in 1X M9 buffer (at a dilution of 1:10) containing 100 μg/ml Ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG. This bacterial suspension was then seeded onto the RNAi plates and dried at room temperature for 2 days before use.

Life span assay

Gravid adult hermaphrodite worms were bleached, washed and the eggs collected by centrifugation. These eggs were allowed to hatch on plates containing the OP50 feed or RNAi bacteria. When they reached young adult stage, they were transferred to NGM OP50 or RNAi plates, overlaid with FUDR (final concentration of 0.1 mg per ml). Worms were scored as dead or alive by prodding them with a platinum wire every 2–3 days. Unhealthy worms or worms that crawled to the sides of the plates were censored from the population. Life span graph was plotted as percentage survival on Y axis and the number of days on the X axis. Life spans are expressed as average life span ± SEM for all the life span experiments. Life span data summary is reported in S1 Table. Some of the life span assays were performed together and as a result, have same controls. For example, Figs 1B and 2B, 6C, 6D, 6E and 6F.

BDR life span assay

BDR was performed as published earlier [1, 2]. Briefly, E. coli HT115 with L4440 plasmid (referred to as control RNAi) was streaked on a LB agar plate, supplemented with Ampicillin (100 μg per ml) and Tetracycline (12.5 μg per ml) and incubated at 37°C for 14–16 hours. A single colony was chosen from this plate and inoculated into 200 ml LB containing Ampicillin (100 μg per ml) in a 2-litre flask and grown at 37°C for 12 hours in an incubator shaker. The bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 rpm, 4°C for 10 minutes, which was then resuspended in S-basal-cholesterol-antibiotics solution (cholesterol 5 μg per ml, Carbenicillin 50 μg per ml, Tetracycline 1 μg per ml, Kanamycin 10 μg per ml) supplemented with 2 mM IPTG. This was then diluted to the required optical density (OD600) using S-basal-cholesterol antibiotics solution, forming different dilutions of bacteria which were kept at 4°C for a maximum of 2 weeks.

Gravid adult worms maintained on OP50 bacterial feed were bleached and eggs were kept on a 60 mm control RNAi-seeded NGM RNAi plate. On reaching young adult stage, FUDR (100 μg per ml) was added to each plate to prevent progeny development. After about 24 hours, approximately 10–15 worms were transferred to each well of a 12-well plate containing 1 ml of S-basal-cholesterol-antibiotics solution with FUDR (100 μg per ml). The plate was kept on a shaker for 1h to remove adhering bacteria. Meanwhile, the diluted bacterial suspensions were aliquot to separate 12-well cell culture plates, 1 ml solution per well along with FUDR at 100 μg per ml. After the worms were washed off the bacteria, 10–12 worms were moved from the S-Basal to the diluted bacterial suspension with the help of a glass pipette connected to a P200 pipette. Every 3–4 days, worms were moved to fresh bacterial solutions. Before this transfer, they were scored for movement by prodding using a platinum wire. FUDR supplementation in diluted bacterial suspension was only required for the first 8 days. Worms that did not respond to gentle prodding with a worm pick were scored as dead and removed. During experiments, the temperature was maintained at 20°C with continuous rotation of plates at 100rpm in an incubator shaker (Innova 42 incubator shaker, New Brunswick Scientific, New Jersey, USA). Bacterial dilutions had OD600 ranging from 3.0, 1.0, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125 and 0.015625. Life span summary is reported in S1 Table. Statistical analysis was performed using Two-way Annova.

Life span assay with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG)

Plates for performing 2-DOG life span were prepared from the same batch of NGM agar as the control plates except that the 2-DOG (Sigma-Aldrich, D8375) was added in the media to a final concentration of 5 mM from a sterile 0.5 M stock solution made in water. Synchronized egg population (100–150) obtained by sodium hypochlorite treatment of gravid worms grown on E. coli OP50, was exposed to control plates (without 2- DOG). At YA stage, approximately 50 worms were transferred to the plates containing 2-DOG and plates without 2-DOG, overlaid with FUDR, in three technical replicates. Worms were scored every alternate day as mentioned above.

Dauer assay

Gravid adult worms were bleached and eggs were kept on OP50-seeded plates and upshifted to 22.5°C in an incubator. After 72h, worms were counted as adults or dauers. Percentage dauers for each strain was calculated and plotted. Two biological repeats, each with at least two technical repeats, were used for averaging.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real time PCR

Eggs were synchronized by overnight starvation. These L1s were then allowed to grow till YA stage. YA worms were collected in M9 buffer after washing thrice to get rid of bacteria and then frozen in Trizol (Invitrogen, USA). The frozen worms were passed through two freeze-thaw cycles and lysed by vigorous vortexing. RNA was extracted by phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol followed by ethanol precipitation. RNA was dissolved in DEPC-treated MQ water and denatured at 65°C for 10 min. The concentration of the RNA was then determined using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, USA). The integrity of the RNA was checked by electrophoresis on a denaturing formaldehyde gel.

First strand cDNA was synthesized using 2.5 μg RNA, employing Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) reaction was set up using DyNAmo Flash SYBR Green master mix (Thermo Scientific, USA) in a Realplex PCR system (Eppendorf, USA), according to manufacturer’s specifications. The gene expression was represented as relative fold change determined after normalizing the ΔCt values to actin, the housekeeping gene. Two-way Annova with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test and Unpaired two-tailed t-test was applied as statistical analysis by using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California).

Autophagosome quantification

Gravid adult worms expressing lgg-1::gfp were bleached and eggs were hatched on OP50 or RNAi bacteria. When they reach the L3 larval stage, worms were anesthetised with 20 mM sodium azide on 2% agarose slides and imaged at 630X using an AxioImager M2 microscope fitted with Axiocam MRc camera (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The autophagosomes were manually scored as GFP puncta in the hypodermal seam cells, seen only at L3stage. At least 15 worms were examined for approximately 3–10 seam cells in each one of them. The total number of puncta per seam cells for each worm was calculated and averaged out. Assay was repeated three times.

Western blotting

Ten micrograms of protein for each sample was resolved on a 15% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked with 5% w/v skimmed milk protein prepared in 0.1% TBST (room temperature, 1 hr). Subsequently, the membrane was incubated overnight with anti-GFP antibody (Novus, USA—Cat. No. NB100-2220; 1:1000 dilution in 0.1% TBST) at 4°C on a rocker-shaker. Following three washes of 5 minutes each in 0.1% TBST, anti-mouse secondary antibody (Abcam, UK—Cat. No. ab6728; 1:5000 dilution in 0.1% TBST) was added to the membrane and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, with rocking. The membrane was then washed three times with 0.1% TBST, each for 5 minutes, at RT on a rocker-shaker. The blot was developed using an ECL reagent (Millipore, USA), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Uncropped blots are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Quantification of fat content by Oil Red O staining

Fat content of worms was determined according to previously published protocols [2, 36]. Prepared in advance (Oil Red O working solution): Oil Red O stain was prepared as 5mg/ml stock in isopropanol and equilibrated on a rocker shaker for a week. The working stock of Oil Red O was prepared by diluting equilibrated stock to 60% with water. Stock was mixed thoroughly and filtered using a 0.22μm filter to remove any particles.

Eggs extracted from gravid adults by sodium hypochlorite treatment were grown till L4 or YA stage. The worms were washed in 1X PBS to remove any attached bacteria and resuspended in 120μl 1X PBS. To this an equal volume of 2X MRWB buffer (160mM KCl, 40mM NaCl, 14 mMNa2EGTA, PIPES pH 7.4, 1mM Spermidine, 0.4mM Spermine, 2% Paraformaldehyde, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol) was added and incubated for 45 minutes on a rocker shaker. The worms were stored at -80°C after slow freezing using liquid nitrogen. For staining, the frozen worms were thawed on ice, then pelleted and washed thrice with 1XPBS. An 120μl aliquot of the working solution of Oil Red O was added to the fixed worms and incubated for an hour on a shaker at room temperature. Following staining, worms were washed thrice with 1X PBS and mounted on 2% agarose slides for visualization using an AxioImager M2 microscope fitted with Axiocam MRc camera. ImageJ software was used to quantify fat stores in the intestine of worms.

Statistical analysis

All p-values were calculated (by unpaired two-tailed t-test or two-way Annova) and graphs were plotted using Graph pad Prism. For life span analysis, Mantel-Cox log rank test using OASIS software available at http://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis [22] was used.

Supporting information

Dauer assay was performed at 22.5 °C. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N = 2 independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis. **P≤0.01.

(PDF)

Representative images showing autophagosomes as GFP puncta in the hypodermal seam cells of L3-staged (A) lgg::gfp and cep-1(gk138);lgg::gfp worms on control or drl-1 RNAi, (B) eat-2(ad116);lgg-1::gfp and eat-2(ad116);cep-1(gk138);lgg-1:gfp, (C) daf-2(e1370);lgg-1::gfp and daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138);lgg-1::gfp. Images were captured at 630X magnification. Inset images represent zoomed-in areas showing one seam cell. Arrows point to autophagosome puncta. Scale bar is 10 μm. (D) The increased autophagosome formation in daf-2(e1370);lgg-1:gfp is unaffected in daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138);lgg-1::gfp. Quantification of GFP puncta for one of two independent experiments is shown. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N = 2 independent experiments. No. of animals analysed n≥17. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was used for statistical analysis. ****P≤0.0001, ns = non-significant. Source data is provided as source data file. (E) Western blot using anti-GFP antibody to detect the unmodified LGG-1 or PE-LGG-1 in daf-2(e1370);lgg-1::gfp and daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138);lgg-1::gfp. β-ACTIN was used as a loading control. One representative blot out of four independent experiments is shown. Experiments were performed at 20°C. Uncropped blots are provided in Supplementary Information file.

(PDF)

Lowering of fat storage in eat-2(ad465) is attenuated in eat-2(ad465);cep-1(gk138). Representative images (upper panel) and quantification (lower panel) for one of four independent experiments is shown. Images were captured at 400X magnification. Scale bar is 20 μm. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N = 2 independent experiments. No. of animals analysed n≥20. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was used for statistical analysis. ****P≤0.0001. Experiments were performed at 20 °C. Source data is provided as source data file.

(PDF)

(A) Life span analysis of cep-1(gk138) (12X-AB) generated earlier [20] as well as WT, grown on control or drl-1 RNAi. Life span was performed at 20°C and details are provided in S1 Table. Mantel-Cox log rank test using OASIS software available at http://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis [22] was used for statistical analysis. (B) The percentage of dauer formed in daf-2(e1370) is enhanced in the genetic double daf-2(e1370);cep-1(gk138) 12X. Dauer assay was performed at 22.5 °C. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. N = 3 independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis. **P≤0.01.

(PDF)

This file contains source data for experimental replicates used in the study and shown in Figs 3A, 3B, 4A and 4B, as well as S2D and S3 Figs. It also contains uncropped blots used in Fig 3D and S2E Fig.

(XLSX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the Molecular Aging lab for their scientific inputs and Dr. Sylvia Lee for reagents. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, University of Minnesota, USA.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The research was supported in part by the National Bioscience Award for Career Development (BT/HRD/NBA/38/04/2016) and SERB-STAR award (STR/2019/000064) to AM, DBT’s Twinning Programme for the NE (BT/PR16823/NER/95/304/2015) to AM and AB, and core funding from the National Institute of Immunology to AM. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by National Institute of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

References

- 1.Panowski SH, Wolff S, Aguilaniu H, Durieux J, Dillin A. PHA-4/Foxa mediates diet-restriction-induced longevity of C. elegans. Nature. 2007;447(7144):550–5. 10.1038/nature05837 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamoli M, Singh A, Malik Y, Mukhopadhyay A. A novel kinase regulates dietary restriction-mediated longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2014;13(4):641–55. 10.1111/acel.12218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabrez SS, Sharma RD, Jain V, Siddiqui AA, Mukhopadhyay A. Differential alternative splicing coupled to nonsense-mediated decay of mRNA ensures dietary restriction-induced longevity. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):306 10.1038/s41467-017-00370-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matai L, Sarkar GC, Chamoli M, Malik Y, Kumar SS, Rautela U, et al. Dietary restriction improves proteostasis and increases life span through endoplasmic reticulum hormesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(35):17383–92. 10.1073/pnas.1900055116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop NA, Guarente L. Two neurons mediate diet-restriction-induced longevity in C. elegans. Nature. 2007;447(7144):545–9. 10.1038/nature05904 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen D, Thomas EL, Kapahi P. HIF-1 modulates dietary restriction-mediated lifespan extension via IRE-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(5):e1000486 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lapierre LR, De Magalhaes Filho CD, McQuary PR, Chu CC, Visvikis O, Chang JT, et al. The TFEB orthologue HLH-30 regulates autophagy and modulates longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2267 10.1038/ncomms3267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinkraus KA, Smith ED, Davis C, Carr D, Pendergrass WR, Sutphin GL, et al. Dietary restriction suppresses proteotoxicity and enhances longevity by an hsf-1-dependent mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2008;7(3):394–404. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00385.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greer EL, Dowlatshahi D, Banko MR, Villen J, Hoang K, Blanchard D, et al. An AMPK-FOXO pathway mediates longevity induced by a novel method of dietary restriction in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2007;17(19):1646–56. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakowski B, Hekimi S. The genetics of caloric restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13091–6. 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Z, Isik M, Moroz N, Steinbaugh MJ, Zhang P, Blackwell TK. Dietary Restriction Extends Lifespan through Metabolic Regulation of Innate Immunity. Cell Metab. 2019;29(5):1192–205.e8. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosono R, Nishimoto S, Kuno S. Alterations of life span in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans under monoxenic culture conditions. Exp Gerontol. 1989;24(3):251–64. 10.1016/0531-5565(89)90016-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz TJ, Zarse K, Voigt A, Urban N, Birringer M, Ristow M. Glucose restriction extends Caenorhabditis elegans life span by inducing mitochondrial respiration and increasing oxidative stress. Cell Metab. 2007;6(4):280–93. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaeberlein TL, Smith ED, Tsuchiya M, Welton KL, Thomas JH, Fields S, et al. Lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans by complete removal of food. Aging Cell. 2006;5(6):487–94. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00238.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolliffe AK, Derry WB. The TP53 signaling network in mammals and worms. Brief Funct Genomics. 2013;12(2):129–41. 10.1093/bfgp/els047 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature. 2002;415(6867):45–53. 10.1038/415045a . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maier B, Gluba W, Bernier B, Turner T, Mohammad K, Guise T, et al. Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev. 2004;18(3):306–19. 10.1101/gad.1162404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer JH, Chang C, Bae G, Morris SN, Helfand SL. Dominant-negative Dmp53 extends life span through the dTOR pathway in D. melanogaster. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131(3):193–201. 10.1016/j.mad.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer JH, Chang C, Morris SN, Hozier S, Andersen S, Waitzman JS, et al. Expression of dominant-negative Dmp53 in the adult fly brain inhibits insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(33):13355–60. 10.1073/pnas.0706121104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baruah A, Chang H, Hall M, Yuan J, Gordon S, Johnson E, et al. CEP-1, the Caenorhabditis elegans p53 homolog, mediates opposing longevity outcomes in mitochondrial electron transport chain mutants. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(2):e1004097 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arum O, Johnson TE. Reduced expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans p53 ortholog cep-1 results in increased longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(9):951–9. 10.1093/gerona/62.9.951 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han SK, Lee D, Lee H, Kim D, Son HG, Yang JS, et al. OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56147–52. 10.18632/oncotarget.11269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen M, Chandra A, Mitic LL, Onken B, Driscoll M, Kenyon C. A role for autophagy in the extension of lifespan by dietary restriction in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(2):e24 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melendez A, Talloczy Z, Seaman M, Eskelinen EL, Hall DH, Levine B. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science. 2003;301(5638):1387–91. 10.1126/science.1087782 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung CK, Empinado H, Choe KP. Depletion of a nucleolar protein activates xenobiotic detoxification genes in Caenorhabditis elegans via Nrf /SKN-1 and p53/CEP-1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(5):937–50. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.12.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matheu A, Maraver A, Klatt P, Flores I, Garcia-Cao I, Borras C, et al. Delayed ageing through damage protection by the Arf/p53 pathway. Nature. 2007;448(7151):375–9. Epub 2007/07/20. 10.1038/nature05949 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Cao I, Garcia-Cao M, Martin-Caballero J, Criado LM, Klatt P, Flores JM, et al. "Super p53" mice exhibit enhanced DNA damage response, are tumor resistant and age normally. EMBO J. 2002;21(22):6225–35. 10.1093/emboj/cdf595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waskar M, Landis GN, Shen J, Curtis C, Tozer K, Abdueva D, et al. Drosophila melanogaster p53 has developmental stage-specific and sex-specific effects on adult life span indicative of sexual antagonistic pleiotropy. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1(11):903–36. 10.18632/aging.100099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer JH, Poon PC, Glatt-Deeley H, Abrams JM, Helfand SL. Neuronal expression of p53 dominant-negative proteins in adult Drosophila melanogaster extends life span. Curr Biol. 2005;15(22):2063–8. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.051 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavernarakis N. Ageing and the regulation of protein synthesis: a balancing act? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18(5):228–35. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.02.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tavernarakis N, Pasparaki A, Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Kroemer G. The effects of p53 on whole organism longevity are mediated by autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4(7):870–3. 10.4161/auto.6730 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ventura N, Rea SL, Schiavi A, Torgovnick A, Testi R, Johnson TE. p53/CEP-1 increases or decreases lifespan, depending on level of mitochondrial bioenergetic stress. Aging Cell. 2009;8(4):380–93. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00482.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Keizer PL, Laberge RM, Campisi J. p53: Pro-aging or pro-longevity? Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2(7):377–9. 10.18632/aging.100178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams AB, Schumacher B. p53 in the DNA-Damage-Repair Process. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(5). 10.1101/cshperspect.a026070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. 2006:1–11. 10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Rourke EJ, Soukas AA, Carr CE, Ruvkun G. C. elegans major fats are stored in vesicles distinct from lysosome-related organelles. Cell Metab. 2009;10(5):430–5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]