Abstract

Background

The lack of diversity in the cardiovascular physician workforce is thought to be an important driver of racial and sex disparities in cardiac care. Cardiology fellowship program directors play a critical role in shaping the cardiology workforce.

Methods and Results

To assess program directors’ perceptions about diversity and barriers to enhancing diversity, the authors conducted a survey of 513 fellowship program directors or associate directors from 193 unique adult cardiology fellowship training programs. The response rate was 21% of all individuals (110/513) representing 57% of US general adult cardiology training programs (110/193). While 69% of respondents endorsed the belief that diversity is a driver of excellence in health care, only 26% could quote 1 to 2 references to support this statement. Sixty‐three percent of respondents agreed that “our program is diverse already so diversity does not need to be increased.” Only 6% of respondents listed diversity as a top 3 priority when creating the cardiovascular fellowship rank list.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that while program directors generally believe that diversity enhances quality, they are less familiar with the literature that supports that contention and they may not share a unified definition of "diversity." This may result in diversity enhancement having a low priority. The authors propose several strategies to engage fellowship training program directors in efforts to diversify cardiology fellowship training programs.

Keywords: disparities, diversity in cardiology, implicit bias, training program directors

Subject Categories: Ethics and Policy

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Thirty‐one percent of cardiology fellowship program director survey respondents are uncertain or do not believe that physician diversity enhances quality of care.

Sixty‐three percent of cardiology fellowship program director survey respondents do not think that diversity needs to be increased in their program.

Only 6% of cardiology fellowship program director survey respondents rank diversity/ability to enhance cultural competency as a “top 3” priority when making their fellowship rank list.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Underrepresented minority and female patients are less likely than majority patients to receive guideline‐based, quality cardiovascular care.

Female and underrepresented minority physicians are more likely to follow evidence‐based clinical guidelines and provide care for underserved patients, respectively.

More diversity in cardiology can reduce cardiovascular healthcare disparities.

Multiple studies have documented racial and sex disparities in cardiovascular care since the 1990s. Women and minorities are less likely than White males to receive implantable defibrillators, biventricular pacemakers, coronary revascularization procedures, and guideline‐based medical therapy post myocardial infarction when clinically indicated. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 One potential driver of these and other disparities is the lack of diversity in the cardiovascular physician workforce. 1

Studies suggest that female physicians are more likely to provide patient‐centered communication and health counseling compared with male physicians, 6 , 7 and patients with female providers were more likely to receive guideline‐recommended treatment for heart failure and diabetes mellitus 6 , 8 and may have better clinical outcomes. 9 Other publications have consistently shown that underrepresented minority (URMs; Hispanic, Black, American Indian, Native Alaskan, Native Hawaiian, Native Pacific Islander) physicians are more likely to care for underserved, Medicaid, and poor patients compared with majority physicians, 10 , 11 , 12 that URM patients prefer race‐concordant physicians and associate them with more empathy for their condition, 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 and that URM patients are more likely to consent to both preventive health services and heart surgery if the recommending physician is also a URM. 17 , 18 Nearly 2 decades ago the Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) recommended diversifying the physician workforce as 1 strategy to reduce healthcare disparities. 19

In 2015, fewer than 6% of practicing cardiologists self‐identified as URMs and only 13.2% were female. 20 , 21 Among cardiology fellows in 2018, 11.6% self‐identified as URM. 22 These numbers stand in stark contrast to the US population in 2015 which was 17.6% Hispanic, 13.3% Black, 1.2% American Indian, and 50.8% female. 23 We firmly believe that racial and sex disparities in cardiovascular care will not be eliminated until we have a cardiology workforce that more closely represents the diversity in this nation. Cardiology fellowship program directors and their selection committees serve as gatekeepers for the specialty.

We surveyed adult cardiology fellowship training program directors and associate program directors to determine their perceptions on diversity and identify barriers to increasing diversity among cardiology trainees. We use these findings to propose actions that may prove useful in diversifying cardiology training programs.

METHODS

Survey Development and Distribution

The full survey is included in the supplementary material (Data S1). Raw data and statistical analyses that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author via email upon reasonable request.

A 12‐question survey (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, CA) was developed by the American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Training Committee Diversity working group (survey included in Data S1). The working group consisted of 10 members and displayed significant diversity (40% female, 20% Black, 10% Hispanic, and 20% Asian/Southeast Asian descent). Additionally, 80% of the working group represented 8 academic university‐based programs (12.5% Professors, 62.5% Associate Professors, and 25% Assistant Professors) and 20% represented 2 private, community‐based practices. Areas of clinical expertise included critical care, cardiovascular imaging, general cardiology, adult congenital heart disease, electrophysiology, and interventional cardiology. The group also consisted of 1 chief of cardiology, 1 program director, 2 associate program directors, 2 echocardiography laboratory directors, 1 Associate Director for Undergraduate Medical Education, and 1 Associate Dean for Medical School Admissions.

Program and associate program directors of adult general and subspecialty cardiology training programs were emailed the survey in October 2016 via a LISTSERVE maintained by the American College of Cardiology. The survey was open to responses for 3 weeks and closed in November 2016. Survey responses were anonymized to encourage honest feedback. For this survey, underrepresented minorities were defined as those self‐identifying as Hispanic, Black, or American Indian.

The study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval according to the American College of Cardiology’s policy of survey‐based studies.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages of the specified group.

RESULTS

Demographics

Program or associate program directors (n=513) representing 193 unique adult general cardiology training programs were emailed the survey. Of these, 110 (21% of all individuals surveyed representing 57% of unique general cardiology training programs) completed the survey. Of the respondents, 92 (84%) reported that female and minority cardiology faculty were underrepresented at their institution as defined by fewer than one third women, <10% URM, or both.

Perceptions on the Benefit of Diversity

Of survey respondents, 69% believed that the following statement was true: “Diversity is a driver of excellence in healthcare delivery (in other words, the more diversity represented amongst healthcare providers, the better the care delivered to patients)”. Of these, 26% could quote 1 to 2 references to support this statement.

Interest in Increasing Diversity in Cardiology Training Programs

When asked about their position on increasing diversity in their cardiology training program, 63% of program directors chose “our program is diverse already so diversity does not need to be increased.” The remaining 37% of respondents want to increase diversity in their program. Of program directors who feel their program is diverse enough, two thirds selected “ability to fit in/team player” as a top 3 criterion considered when generating the rank list for the National Residency Matching Program.

Of the 37% of program directors interested in increasing diversity in their programs, less than half stated they have a plan to achieve this goal. Plans listed to increase diversity included: having current fellows (including URMs) directly recruit diverse applicants; increasing the total number of applicants interviewed to interview more female and URM applicants; actively placing a URM candidate higher when ranking 2 similarly qualified candidates (URM and non‐URM); creating a website for minority candidates to go to for information; increasing the number of female faculty on staff and including female faculty members in recruitment efforts; increasing the number of URM faculty; intentionally including women and a diverse spectrum of cultural backgrounds when selecting candidates to interview; targeting candidates who represent the cultural, ethnic, and sex‐base of the community; coordinating with the institution’s diversity office to offer second‐look interviews including a meet and greet with trainees and diverse faculty in leadership roles; interview all qualified URM candidates; reaching out to program directors at other institutions to encourage URM applicants to apply; and encouraging home institution URM residents to apply to cardiology.

Recruitment and Ranking Practices

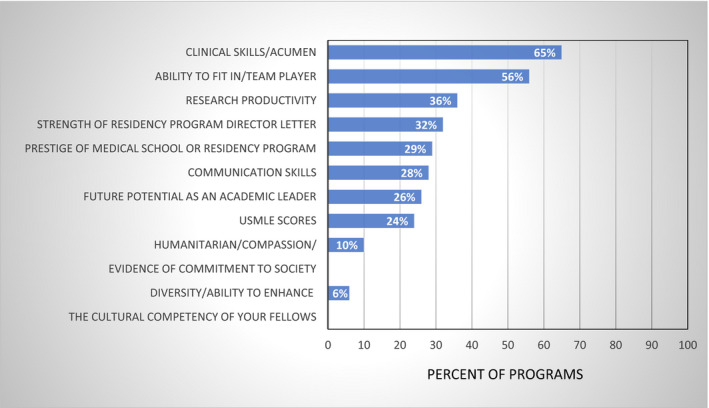

During meetings to rank cardiology fellowship applicants, 55% of program directors stated that both women and URM faculty are present. However, 45% said that either women (4%), URMs (31%), or both (10%) are not present at the meeting to rank cardiology fellowship applicants. The top 3 criteria considered when ranking candidates for the cardiology fellowship “rank list” are listed in Figure. The top 3 criteria were clinical skills/acumen (in the top 3 of 65% of respondents), ability to fit in/team player (in the top 3 of 56% of respondents), and research productivity (in the top 3 of 36% of respondents). Interestingly, of the 84% of respondents who said women or URMs were significantly underrepresented among the faculty at their institution, two thirds listed “ability to fit in well/team player” as a top 3 consideration when creating the fellowship rank list. Only 6% of respondents listed "diversity/ability to enhance cultural competency of the program" as one of the top 3 criteria considered when creating the rank list.

Figure 1. Top 3 criteria considered when ranking candidates (% of respondents who considered criterion a “top 3” priority, n=110).

USMLE indicates United States Medical Licensing Exam.

With respect to recruitment, among the survey respondents, 82% stated their programs participate in recruitment activities. The most frequently reported recruitment activity was keeping the website updated (72%), followed by having current fellows reach out to candidates to answer questions (54%). A few programs offered second interviews (15%) or used social media (5%).

DISCUSSION

This report on cardiology program director perceptions on diversity has several important findings. In a specialty where diversity is severely lacking among practitioners and trainees, 63% of program director respondents feel that diversity in their programs is adequate and does not need to be increased. A sizable minority (31%) of respondents are uncertain whether diversity among healthcare providers enhances quality of care and a large majority (74%) of those who believe that diversity enhances quality are unable to cite studies supporting that contention. Finally, among those interested in increasing diversity in their training programs, many are uncertain of how to do so. Our findings suggest that opportunities exist to engage and partner with cardiology training program directors and cardiology divisions to increase diversity in training programs. We propose several strategies to engage program directors in efforts to diversify the profession and pipeline of cardiology training programs.

The barriers identified by our survey with proposed action items are outlined in Table 1. The uncertainty about the impact of a diverse workforce on the quality of care and lack of familiarity with the relevant literature indicate an opportunity for education.

Table 1.

Barriers to Increasing Diversity and Proposed Actions

| Barriers/Misperceptions | Actions |

|---|---|

| Lack of familiarity with diversity literature | Required readings/modules for PDs/APDs |

| “Diversity does not need to be enhanced …” | Compare program demographics to local/target community |

| Diversity not a priority when ranking | Make “diversity/ability to enhance cultural competency” a top 3 priority when ranking |

| PDs indifferent to “recruiting” | Recruit actively for diversity in immediate pipeline |

| Develop “deep pipeline” of talent from local HS and universities |

APD indicates Associate Program Director; HS, high school; and PD, Program Director.

We propose that cardiology divisions offer lectures, online learning modules, workshops/discussions, and journal clubs to disseminate information on the benefits of diversity in medicine, and that such scholarly articles be considered required readings for program directors and fellowship selection committee members. Tables 2 and 3 provide key references on the impact of URM and female physicians on quality and equitable patient care.

Table 2.

Key References on the Benefits of Female Physicians

Table 3.

Key References on the Benefits of URM Physicians

| Minority Physicians More Likely to Serve the Underserved; Minority Patients Prefer Race‐Concordant Physicians and More Likely to Comply With Recommendations by Minority Physicians |

|---|

| Jackson. Public Health Rep. 2014 10 |

| Marrast. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 11 |

| Brotherton. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 12 |

| Cooper. Ann Intern Med. 2003 13 |

| Gordon. Cancer. 2006 15 |

| Traylor. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 16 |

| Alsan. Am Econ Rev. 2019 17 |

| Saha. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 18 |

URM indicates underrepresented minority.

To address the perception that individual program diversity does not need to be increased, we suggest that individual programs compare their demographics against the national and local population in the community they serve. When asked to prioritize attributes of fellowship candidates when making the rank list, only 6% of respondents selected "diversity/ability to enhance cultural competency of the program" as a top 3 priority. We propose that, consistent with recently updated accreditation standards of the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education, 24 programs consider making diversity a high priority throughout the application cycle and when making the final rank lists. Doing so can be an important part of a strategy to enhance diversity in cardiology training programs. 25

Survey responses regarding recruiting strategies, such as having diverse fellows reach out to applicants or keeping the program website updated, appear to focus on the immediate pipeline of internal medicine residents. Since women now make up more than half of all medical students and nearly 50% of internal medicine residents, these tactics can be an important part of an overall strategy to increase the number of female cardiologists. However, URM talent is severely underrepresented all along the pipeline. Accordingly, the American College of Cardiology Diversity and Inclusion Task Force recommends engagement with talent in the "deep pipeline." 26 We endorse this recommendation, and propose that cardiology training programs and their cardiology divisions partner with colleges, high schools, and even elementary schools to expose minorities and girls/women to cardiology as a profession.

Barriers to women entering adult cardiology training programs have been reported and include sex disparities in pay, promotion, and grant funding. 27 , 28 , 29 These findings have led to a perception that cardiology is unwelcoming to women. 30 Implicit and explicit bias in the selection process may also put women and URM candidates at a disadvantage. Our finding that respondents who feel their program is "diverse enough" tended to select “ability to fit in/team player” as a top 3 criterion when ordering the rank list, which suggests that candidates who look, act, or think differently than a program’s typical fellows may be at a disadvantage.

A recent study found that male and female surgeons were more likely to unconsciously associate women with "homemakers" and men with "professionals" and male doctors with “surgeon” and female doctors with “family physician.” 31 Such implicit biases may influence advisors to steer young women towards non‐procedure‐based specialties. To overcome these barriers, we recommend active efforts to promote a culture that is more inclusive of women, including the following: implicit bias mitigation training of cardiology faculty, fellowship program directors, selection committee members, and senior leaders of the organization; highlighting female faculty and fellows on websites and promotional literature marketing the fellowship program; early mentorship for female medical students and residents and junior faculty members; and providing specific information about radiation exposure during training, a topic that concerns some women who might consider cardiology. These strategies also hold promise to enhance URM diversity.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, our survey response was 21% of those individuals surveyed. However, these respondents represented 57% of adult cardiology training programs. Second, we did not ask respondents to identify whether they were program directors or associate program directors. As a result, we cannot say what portion of our respondents were program directors versus associate program directors. However, associate program directors play a prominent role in recruiting, evaluating, and ranking fellowship applicants. Also, because our survey was anonymous we cannot correlate individual responses with specific program attributes. Finally, our survey was limited to perceptions about diversity with regard to URMs and women. We did not specifically address other underrepresented populations in cardiology such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning populations, those with disabilities, or international medical graduates.

Conclusions

Many medical and surgical specialties lack racial and sex diversity and multiple recent publications propose strategic initiatives to enhance diversity. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 To our knowledge, this is the first to focus on program directors’ perceptions of diversity and barriers to increasing diversity. Our survey of cardiology program directors and associate program directors found that (1) a sizable minority of respondents are uncertain about the benefits of diversity; (2) that a majority were unfamiliar with the published literature citing the benefits of diversity; and (3) that many did not prioritize increasing diversity during recruitment in 2016. We propose several strategies that may assist training programs as they work to follow the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education recommendation to enhance diversity in training programs. Such actions are critical to ongoing efforts to eliminate racial and sex disparities in cardiovascular care.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by the American College of Cardiology.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017196 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017196.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 6.

References

- 1. Capers Q IV, Sharalaya Z. Racial disparities in cardiovascular care: a review of culprits and potential solutions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, McNamara RL, Webster TR, Magid DJ, Blaney M, Peterson ED, Canto JG, Pollack CV, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in time to acute reperfusion therapy for patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2004;292:1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sheifer SE, Escarce JJ, Schulman KA. Race and sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2000;139:848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sonel AF, Good CB, Mulgund J, Roe MT, Gibler WB, Smith SC Jr, Cohen MG, Pollack CV, Ohman EM, Peterson ED, et al. Racial variations in treatment and outcomes of black and white patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines?). Circulation. 2005;111:1225–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathews R, Chen AY, Thomas L, Wang TY, Chin CT, Thomas KL, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Differences in short-term versus long-term outcomes of older black versus white patients with myocardial infarction: findings from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines (CRUSADE). Circulation. 2014;130:659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumhakel M, Muller U, Bohm M. Influence of gender of physicians and patients on guideline-recommended treatment of chronic heart failure in a cross-sectional study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:299–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and Patient‐centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmittdiel JA, Traylor A, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Ferrara A, Subramanian U. The association of Patient‐physician gender concordance with cardiovascular disease risk factor control and treatment in diabetes. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18:2065–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson CS, Gracia JN. Addressing health and health- care disparities: the role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl 2):57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brotherton SE, Stoddard JJ, Tang SS. Minority and nonminority pediatricians' care of minority and poor children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, Ford DE. Race, gender, and partnership in the Patient‐physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gordon HS, Street RL Jr, Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors' information-giving and patients' participation. Cancer. 2006;107:1313–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does Patient‐provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1172–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109:4071–4111. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saha S, Beach MC. Impact of physician race on patient decision-making and ratings of physicians: a randomized experiment using video vignettes. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1084–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Table 8. 2017. Available at: http://aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/section-v-additional-detailed-tables/-tab8. Accessed October 17, 2017.

- 21.Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/458712/1-3-chart.html. Accessed October 17, 2017.

- 22. Santosh L, Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1920482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. US Census Data . Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/. Accessed October 17, 2017.

- 24.Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020. Accessed February 29, 2020.

- 25. Auseon AJ, Kolibash AJ Jr, Capers Q. Successful efforts to increase diversity in a cardiology fellowship training program. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Douglas PS, Williams KA, Walsh MN. Diversity matters. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1525–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jagsi R, Biga C, Poppas A, Rodgers GP, Walsh MN, White PJ, McKendry C, Sasson J, Schulte PJ, Douglas PS. Work activities and compensation of male and female cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:529–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, Yeh DD, Sarma A, Schmidt ACS, Wood M, Jena AB. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation. 2017;135:506–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaatz A, Lee YG, Potvien A, Magua W, Filut A, Bhattacharya A, Leatherberry R, Zhu X, Carnes M. Analysis of National Institutes of Health R01 application critiques, impact, and criteria scores: does the sex of the principal investigator make a difference? Acad Med. 2016;91:1080–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Douglas PS, Rzeszut AK, Bairey Merz CN, Duvernoy CS, Lewis SJ, Walsh MN, Gillam L. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:682–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Salles A, Awad M, Goldin L, Krus K, Lee JV, Schwabe MT, Lai CK. Estimating implicit and explicit gender bias among health care professionals and surgeons. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e196545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adelani MA, Harrington MA, Montgomery CO. The distribution of underrepresented minorities in U.S. orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Nkanyezi NF, Hu S, Ortega-Loayza AG, Lim HW. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Derm. 2018;79:337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Silvestre J, Serletti JM, Chang B. Racial and ethnic diversity of US plastic surgery trainees. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. March JA, Adams JL, Portela RC, Taylor SE, McManus JG. Characteristics and diversity of ACGME accredited emergency medical services fellowship programs. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23:551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1