Abstract

Background

Impaired global coronary flow reserve (g‐CFR) is related to worse outcomes. Inflammation has been postulated to play a role in atherosclerosis. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between pre‐procedural pericoronary adipose tissue inflammation and g‐CFR after the urgent percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with first non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Methods and Results

Phase‐contrast cine‐magnetic resonance imaging was performed to obtain g‐CFR by quantifying coronary sinus flow at 1 month after percutaneous coronary intervention in a total of 116 first non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome patients who underwent pre‐percutaneous coronary intervention computed tomography angiography. On proximal 40‐mm segments of 3 major coronary vessels on computed tomography angiography, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation was assessed by the crude analysis of mean computed tomography attenuation value. The patients were divided into 2 groups with and without impaired g‐CFR divided by the g‐CFR value of 1.8. There were significant differences in age, culprit lesion location, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide levels, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP) levels, mean pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation between patients with impaired g‐CFR and those without (g‐CFR, 1.47 [1.16, 1.68] versus 2.66 [2.22, 3.28]; P<0.001). Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that age (odds ratio [OR], 1.060; 95% CI, 1.012–1.111, P=0.015) and mean pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation (OR, 1.108; 95% CI, 1.026–1.197, P=0.009) were independent predictors of impaired g‐CFR (g‐CFR <1.8).

Conclusions

Mean pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation, a marker of perivascular inflammation, obtained by computed tomography angiography performed before urgent percutaneous coronary intervention, but not hs‐CRP, a marker of systemic inflammation was significantly associated with g‐CFR at 1‐month after revascularization. Our results may suggest the pathophysiological mechanisms linking perivascular inflammation and g‐CFR in patients with non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, coronary flow reserve, inflammation, microvascular resistance, non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome

Subject Categories: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CS

coronary sinus

- CSF

coronary sinus flow

- FFR

fractional flow reserve

- g‐CFR

global coronary flow reserve

- hs‐CRP

high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein

- LGE

late gadolinium enhancement

- PCATA

pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation

- PC‐CMR

phase‐contrast cine‐magnetic resonance imaging

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

pre‐percutaneous coronary intervention pericoronary adipose tissue inflammation assessed by pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation derived from computed tomography angiography was significantly associated with global coronary flow reserve evaluated by phase‐contrast cine‐magnetic resonance imaging at 1 month after urgent percutaneous coronary intervention, independent of myocardial injury by the index non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome.

This relationship is independent of high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, a marker of systemic inflammation, and conventional risk factors.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation obtained at admission may be useful to stratify high‐risk patients of future cardiac events early after admission before urgent intervention in non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome patients.

Future therapeutic strategies directed towards reducing pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation that represent the specific inflammatory status of the cardiovascular system may potentially provide a novel management option in patients with non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Incidence of non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE‐ACS) has been reported to increase and show a wide heterogeneity in its presentation. 1 , 2 Although early revascularization is shown to be associated with improved outcomes for NSTE‐ACS, NSTE‐ACS is still associated with higher rates of major adverse cardiac events compared with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction, even after successful revascularization. 2 , 3 Given this background, tools for early identifying patients with NSTE‐ACS at high risk for worse outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are increasingly needed.

Phase‐contrast cine‐magnetic resonance imaging (PC‐CMR) allows non‐invasive quantification of myocardial blood flow and global coronary flow reserve (g‐CFR) by quantifying coronary sinus flow (CSF) without need for ionizing radiation, radioactive tracers, gadolinium, or intravascular catheterization myocardial blood flow and g‐CFR are important predictors for worse outcomes in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease (CAD). 4 , 5 , 6

Recently, it has been reported that the pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation (PCATA) on computed tomography angiography (CTA) was also associated with cardiac mortality. 7 The mean computed tomography (CT) attenuation values of pericoronary adipose tissue have been demonstrated to be linked with adipocyte lipid content quantified by histology and 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography, indicating that PCATA is significantly associated with perivascular inflammation. 8 Inflammation has long been postulated to play an important role in the atherosclerotic progression and the rupture of vulnerable coronary plaque and subsequent acute coronary syndrome. 9 , 10 , 11 The Canakinumab Antiinflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study randomized trial further helped our understanding of the inflammatory hypothesis of CAD by showing the link with anti‐inflammatory therapy and the reduction of recurrent cardiovascular events. 12 To date, no study has been reported on PCATA and g‐CFR in patients with NSTE‐ACS undergoing urgent PCI.

Thus, the hypothesis tested was that pre‐PCI pericoronary vascular inflammation is associated with g‐CFR at 1‐month post‐PCI in successfully revascularized patients with NSTE‐ACS. To test this hypothesis, the present study was undertaken in patients with first NSTE‐ACS who underwent pre‐PCI CTA and successful urgent PCI within 48 hours from admission.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This study was a post‐hoc analysis of prospectively, but non‐consecutively enrolled patients in NSTE‐ACS CTA registry at Tsuchiura Kyodo General Hospital, which tested the hypothesis that CTA before invasive coronary angiography may provide the diagnostic information of atherosclerotic burden, lesion location and procedural planning of revascularization with a relatively low dose of radiation and contrast in patients with suspected NSTE‐ACS. In this study, 351 patients with suspected ischemic chest pain and stable hemodynamics underwent CTA from April 2017 to March 2019. A total of 183 patients with suspected first NSTE‐ACS who underwent pre‐PCI CTA and subsequent coronary angiography with ad‐hoc successful PCI and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) were enrolled in the present study. Of these 183 patients, 121 patients gave written informed consent for the present study to undergo PC‐CMR at 1 month (28±4 days) and were studied. We included patients aged at least 20 years who were admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of NSTE‐ACS within 48 hours of the last appearance of symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia and/or ST‐T segment change in at least 2 leads, and who underwent successful PCI with an early invasive strategy <48 hours after admission. 3 We included patients with unstable angina pectoris and non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction when the single culprit lesion was identifiable and considered suitable for PCI. We excluded patients with significant left main CAD, chronic total occlusion, unidentifiable culprit lesions, significant valvular disease, previous coronary artery bypass grafting, previous myocardial infarction, significant arrhythmia, renal insufficiency with a baseline serum creatinine level >1.5 mg/dL, and contraindication to CMR (eg, pacemaker, internal defibrillator, or other incompatible intracorporeal foreign bodies, pregnancy, and claustrophobia). Patients with visible side branch occlusion (>1.5 mm) and those with ST‐segment elevation after PCI were also excluded. Patients with a thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade 2 after PCI were included if they met none of the exclusion criteria. We defined successful and uncomplicated PCI as a reduction of the minimum stenosis diameter <20% without the no‐reflow phenomenon (TIMI flow grade risk score of 0 or 1) and clinical improvement of symptoms and/or ST‐T segment change. Patients with multi‐vessel CAD, who exhibited additional angiographic stenosis >50% in at least 1 coronary artery other than the culprit vessel were eligible for inclusion. When the non‐infarct‐related coronary arteries had lesions with diameter stenosis of 30% to 90% by visual estimation, the fractional flow reserve (FFR) was measured. Non‐culprit lesions were considered significant in the case of either FFR ≤0.80 or a visually assessed diameter stenosis ≥90%, and these significant non‐infarct‐related artery stenoses were considered as candidates for revascularization at the time of the index urgent PCI or as a planned staged procedure during the index hospitalization. Unsuitable lesions for PCI, including heavily calcified lesions, diffuse lesions, and lesions with small subtended myocardial mass, were left untreated on the consensus of the institutional heart team. The second‐stage procedure was performed between 3 and 7 days after the index procedure. CMR imaging was performed after non‐infarct‐related lesion revascularization in all patients. Prompt optimal medical therapy was initiated in all patients after enrollment. We applied a standardized protocol to measure systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate twice in the left arm of seated subjects between 8 and 11 am, following the recommendations of The American Heart Association, and the mean values of 3 to 5 days after urgent PCI were used for the analysis. The study protocol agreed with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment in this study.

Cardiac Catheterization

Invasive coronary angiography and revascularization of the infarct‐related artery were performed with ad‐hoc PCI via the routine use of drug‐eluting stents with a 6‐Fr system. Before the PCI procedure, all patients received a loading dose of 200 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel or 20 mg prasugrel. Coronary angiograms were analyzed quantitatively using a QAngio XA system (Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, The Netherlands). The stent type and procedure strategy selected were at the operator's discretion. To avoid aggressive stent expansion, online quantitative coronary angiography was used to determine the correct stent size. After reperfusion therapy, standard dual antiplatelet therapy was started according to current guidelines. Physiological measurements (FFR) were performed for all lesions showing intermediate stenosis (visual estimation between 30% and 90% diameter stenosis). All patients were instructed to strictly refrain from ingesting caffeinated beverages after admission. FFR was determined using a Radi Analyzer Xpress instrument with a Certus coronary pressure wire (Abbott Vascular, St. Paul, MN, USA). FFR was calculated as the ratio of the mean distal coronary pressure to the mean aortic pressure during stable hyperemia induced by intravenous adenosine (140 μg/kg per minute through a central vein).

Coronary CTA Acquisition

CT imaging was performed using a 320‐slice CT scanner (Aquilion ONE; Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Tochigi, Japan) in accordance with the society of cardiovascular CT guidelines. 13 When needed, oral and/or intravenous beta‐blockers were administered to achieve a target heart rate ≤65 bpm. A non‐contrast enhanced CT‐scan for the assessment of coronary artery calcification, prospectively triggered at 75% of the RR‐interval with 3 mm slice thickness, was followed by CTA. Immediately before CTA scanning, 0.3 or 0.6 mg of sublingual nitroglycerine was administered. The scan was triggered using an automatic bolus‐tracking technique with a region of interest placed in the ascending aorta. Images were acquired after a bolus injection of 40 to 60 mL contrast (iopamidol, Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Japan) at a rate of 3–6 mL/s, using prospective ECG‐triggering or retrospective ECG gating with tube current modulation. Acquisition and reconstruction parameters for the patients in our study were 120 kVp, tube current of 50 to 750 mA, gantry rotation speed of 350 ms per rotation, helical pitch of 8 to 18, field matrix of 512×512, and scan thickness of 0.5 mm. All scans were performed during a single breath‐hold. Images were reconstructed at a window centered at 75% of the R‐R interval to coincide with left ventricular diastasis. In the present study, CTA images were blindly analyzed by the 2 independent engineers at the institutional imaging and physiology laboratory immediately after the CTA examination and the results were reported to the attended physicians and interventionalists.

Analysis of PCATA

The proximal right coronary artery has been used in prior studies for CTA attenuation analysis and represents a standardized model for pericoronary inflammation analysis. 7 , 8 In the present study, crude analysis of PCATA of all 3 main coronary vessels was performed and the mean PCATA of 3 main coronary vessels was used for the analysis. PCATA analysis was performed using a dedicated workstation (Aquarius iNtuition Edition version 4.4.13; TeraRecon Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). The proximal 40 mm segments of the left anterior descending artery and left circumflex artery and the proximal 10 to 50 mm segment of the right coronary artery were traced, as previously described. 7 CT measurement of PCATA was fully automated with an additional minor manual optimization. PCAT was sampled in 3‐dimensional layers, moving radially outwards from the outer vessel wall equal to the diameter of the coronary vessel.

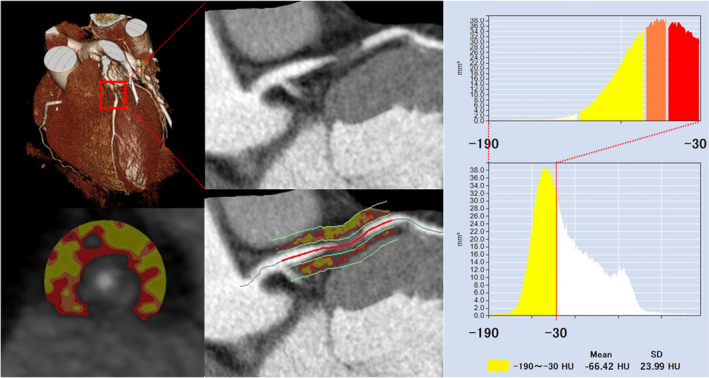

Adipose tissue was defined as all voxels with attenuation between −190 HU and −30 HU, and the PCATA was defined as the average CT attenuation in Hounsfield units of the adipose tissue within the defined volume of interest (Figure 1). PCATA analysis was separately performed as a post‐hoc analysis blinded to the results of angiography findings and clinical data at the institutional imaging and physiology laboratory by the expert investigator for PCATA analysis.

Figure 1. Representative coronary computed tomography angiography image of pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation around the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery.

Pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation is defined as the mean computed tomography attenuation value (−190 to −30 HU) within a radial distance equal to the diameter of the vessel. CT indicates computed tomography; and LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery.

CT‐Derived Left Ventricular Mass Index and Cardiac Mass at Risk

Quantitative assessments of left ventricular (LV) mass were performed using the Aquarius iNtuition Workstation Edition version 4.4.13 (TeraRecon Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) at mid‐diastole phase as previously described. 14 , 15 The cardiac mass was calculated as the LV myocardial volume derived by manually corrected automated delineation of the epicardial and endocardial contours and multiplied with the specific gravity of myocardial tissue (×1.055 g/mL). Papillary muscles were not included in the calculation of LV mass. LV mass was indexed by body surface area (LV mass/body surface area; left ventricular mass index).

Coronary artery–based myocardial segmentation was performed to evaluate a coronary lesion‐specific cardiac mass by using the same dedicated software (Aquarius iNtuition Edition version 4.4.13; TeraRecon Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) by the expert investigator masked to the clinical, angiographic, and physiological data as a post‐hoc analysis. The coronary tree and LV myocardium were extracted semi‐automatically, and the cardiac mass at risk was defined as the myocardial mass subtended distal to the culprit lesion identified by using CTA. The percentage cardiac mass at risk was defined as the percentage ratio of the subtended cardiac mass to the LV myocardial mass. The myocardial territories of the 3 coronary arteries and subtended myocardium by the functionally significant stenotic lesion were assigned using the 3‐dimensional Voronoi algorithm.

CMR Image Acquisition and Coronary Sinus Flow Measurement

The coronary sinus (CS) was identified in the atrioventricular groove using the basal slices of the short‐axis stack. The plane for flow measurement by PC‐CMR was positioned perpendicular to the CS at 1 to 2 cm from the ostium. 16 Velocity‐encoded images were acquired using retrospective ECG gating during 15‐second breath holds, and the imaging parameters were as follows: repetition time/echo time, 7.3/4.4 ms; flip angle, 10°; field of view, 250×250 mm2; acquisition matrix, 128×128; 20 phases per cardiac cycle; encoding, 50 cm/s; and slice thickness, 6 mm. PC‐CMR of the CS flow measurements was performed during maximal hyperemia and at rest. Maximal stable hyperemia was induced by intravenous adenosine (140 μg/kg per minute through a central vein). The duration between the end of hyperemia and the resting image acquisition was 10 minutes. All patients were instructed to strictly refrain from caffeinated beverages for >24 hours before CMR examinations. The total CMR examination time for a standard cine‐CMR and CSF measurement was about 20 minutes.

G‐CFR Measurement by CMR

The CSF quantitative analyses were performed in a masked fashion by 2 expert investigators (H. H and Y. K), using proprietary software (Philips View Forum, Best, The Netherlands). The CS contour was traced on the magnitude images throughout the cardiac cycle. The CSF was quantified by integrating the flow rates from each cardiac cycle and multiplying them by the mean heart rate during the acquisition period. The resting CSF value was corrected using rate pressure products as follows 16 , 17 ; rate pressure product=systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)×heart rate; corrected CSF=(CSF/rate pressure product)×10 000; and corrected CSF (mL/min per g)=corrected CSF/LV mass (g). G‐CFR was evaluated by CSF reserve, which was calculated as CSF during maximal hyperemia divided by resting CSF. Coronary vascular resistance was defined as the mean arterial blood pressure (mm Hg) divided by corrected CSF (mL/min).

Statistical Analysis

The patients were divided into 2 groups by the lowest quartile of the g‐CFR (1.8). Clinical characteristics, CTA‐derived data, and CMR‐derived variables were compared between these 2 groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages and compared by Chi‐square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. Continuous data were expressed as median (interquartile range) and analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test and ANOVA for variables with non‐normal distribution and normal distribution to evaluate the difference between the group with and without impaired g‐CFR, respectively. Correlations between 2 variables were assessed using Pearson correlation analysis. Univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to determine predictive factors of g‐CFR (stepwise‐forward method; P<0.05). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were also performed to predict g‐CFR <1.8 (impaired g‐CFR, lowest quartile g‐CFR group) The Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic was applied to assess model calibration. The prediction model for g‐CFR <1.8 was constructed to determine the incremental discriminatory and reclassification performance of physiological parameters for mean PCATA by using relative integrated discrimination improvement and category‐free net reclassification index.

Results

Patient Characteristics

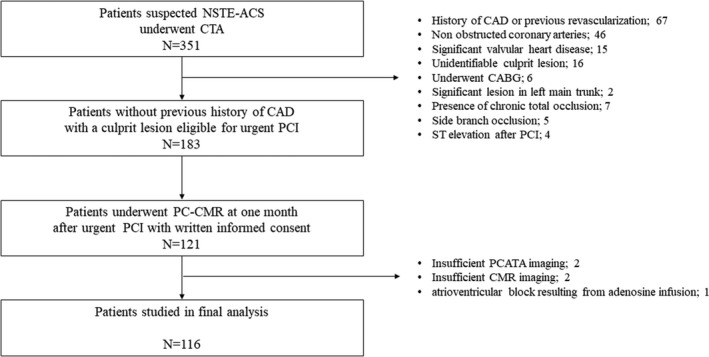

From initially studied 121 patients, 2 patients were excluded from the final analysis because of suboptimal CTA image quality for PCATA analysis, and 2 patients were also excluded because of unsatisfactory CMR data acquisition. One other patient could not complete the CMR examination because of the atrioventricular block and bradycardia resulting from adenosine infusion. Thus, the final analysis was done by 116 patients in the present study (Figure 2). The patients' baseline characteristics in the 2 groups divided by the presence or absence of impaired g‐CFR (g‐CFR; 1.47 [1.16, 1.68] versus 2.66 [2.22, 3.28]; P<0.001) are summarized in Table 1. In a total of 116 patients, the median door‐to‐balloon time was 6.8 [4.0–24] hours, and 60 (51.7%) patients showed multi‐vessel disease (angiographic diameter stenosis >50%). In these patients, 42 patients showed 46 functionally significant lesions and 38 lesions of 34 patients underwent successful non‐infarct‐related vessel PCI. PCI was deferred in the remaining 8 patients based on the institutional heart team decisions. Age, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) levels, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP) levels, and mean PCATA of 3 major vessels were greater in the group with impaired g‐CFR compared with those without (P=0.029, 0.030, 0.010, 0.026, respectively). There was a significant difference in culprit lesion location (P=0.026). Baseline CSF was significantly higher and hyperemic absolute flow was significantly lower, resulting in lower g‐CFR in the impaired g‐CFR group. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), LV ejection fraction, and the levels of peak cardiac marker elevation were not different between the 2 groups.

Figure 2. Study flowchart.

Figure shows the screening and enrollment process with a total of 116 patients in final analysis. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CTA, computed tomography angiography; NSTE‐ACS, non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome; PC‐CMR, phase‐contrast cine‐magnetic resonance imaging; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With and Without Impaired g‐CFR (g‐CFR <1.8)

| Total (n=116) | With Impaired g‐CFR (n=29) | Without Impaired g‐CFR (n=87) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 65±11 | 69±12 | 64±10 | 0.03 |

| Male, n (%) | 92 (79.3) | 25 (83.3) | 59 (81.9) | 0.6 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.698 (1.568–1.816) | 1.652 (1.506–1.747) | 1.722 (1.584–1.839) | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure at presentation, mm Hg | 122±11 | 121±12 | 123±11 | 0.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at presentation, mm Hg | 71±9 | 69±9 | 71±10 | 0.2 |

| Mean blood pressure at presentation, mm Hg | 88±9 | 86±8 | 89±9 | 0.2 |

| Heart rate at presentation, bpm | 69±11 | 67±12 | 70±11 | 0.2 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 78 (67.2) | 19 (65.5) | 59 (67.8) | 0.8 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 61 (52.6) | 16 (55.2) | 45 (51.7) | 0.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 42 (36.2) | 10 (34.5) | 32 (36.8) | 0.8 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 46 (39.7) | 10 (34.5) | 36 (41.4) | 0.5 |

| Family history, n (%) | 12 (10.3) | 1 (3.4) | 11 (12.6) | 0.2 |

| Prescription at admission | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 23 (19.8) | 7 (24.1) | 16 (18.4) | 0.9 |

| Statin, n (%) | 25 (21.6) | 7 (24.1) | 18 (20.7) | 0.7 |

| ACE‐I or ARB, n (%) | 40 (34.5) | 8 (27.6) | 32 (36.8) | 0.4 |

| β‐blocker, n (%) | 8 (6.9) | 3 (10.3) | 5 (5.7) | 0.4 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 45 (38.8) | 13 (44.8) | 32 (36.8) | 0.4 |

| NSTE‐ACS presentation | ||||

| NSTEMI/UAP, n (%) | 86 (74.1)/30 (25.9) | 22 (75.9)/7 (24.1) | 64 (73.6)/23 (26.4) | 0.8 |

| Killip class, n (%) | 0.1 | |||

| I | 109 (94.0) | 25 (86.2) | 84 (96.6) | |

| II | 4 (3.4) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (2.3) | |

| III | 3 (2.6) | 2 6.9) | 1 (1.1) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| GRACE score | 124 (106–146) | 126 (110–153) | 123 (104–143) | 0.3 |

| Coronary angiography | ||||

| Culprit lesion location; RCA/LAD/LCx, n (%) | 32 (27.6)/56 (48.3)/28 (24.1) | 13 (44.8)/13 (44.8)/3 (10.3) | 19 (21.8)/43 (49.4)/25 (28.7) | 0.03 |

| TIMI flow grade at baseline, n (%) | 0.06 | |||

| 0 | 14 (12.1) | 7 (24.1) | 7 (80) | |

| 1 | 6 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.9) | |

| 2 | 27 (23.3) | 5 (17.2) | 22 (2.3) | |

| 3 | 89 (59.5) | 17 (58.6) | 52 (59.8) | |

| TIMI flow grade at final, n (%) | 0.2 | |||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 8 (6.9) | 3 (10.3) | 5 (5.7) | |

| 3 | 108 (93.1) | 26 (89.7) | 82 (94.3) | |

| Multi‐vessel disease, n (%) | 60 (51.7) | 17 (58.6) | 43 (49.4) | 0.4 |

| ad‐hoc PCI of the non‐infarct‐related artery during the index procedure, n (%) | 8 (6.9) | 3 (10.3) | 5 (5.7) | 0.4 |

| Staged PCI of the non‐infarct‐related artery during the index hospitalization, n (%) | 26 (22.4) | 8 (27.6) | 18 (20.7) | 0.4 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| T‐chol, mg/dL | 192 (165–214) | 199 (179–209) | 187 (160–217) | 0.4 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 114 (91–148) | 114 (103–150) | 114 (89–142) | 0.7 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 46 (40–54) | 48 (42–60) | 45 (40–53) | 0.2 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 116 ([78–183) | 109 (72–188) | 122 (81–180) | 0.7 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.79 (0.64–0.91) | 0.85 (0.70–0.96) | 0.77 (0.63–0.88) | 0.03 |

| eGFR, mL·min−1·1.73m−2 | 74.2 (62.2–86.5) | 66.1 (60.1–80.1) | 75.4 (64.2–87.9) | 0.1 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.1 (5.6–7.0) | 6.2 (5.7–6.7) | 6.1 (5.6–7.0) | 0.8 |

| NT‐proBNP, ng/L | 244.5 (113.5–842.0) | 472.0 (154.8–1182.5) | 222.0 (103.0–594.8) | 0.03 |

| cTnI at presentation, ng/L | 149.5 (30.0–1097.5) | 230.0 (28.3–4847.8) | 137.0 (30.0–499.8) | 0.3 |

| Peak CK, IU/L | 248 (126–688) | 306 (171–740) | 216 (119–642) | 0.2 |

| Peak CK‐MB, IU/L | 24 (13–58) | 32 (17–63) | 19 (12–55) | 0.2 |

| hs‐CRP, mg/dL | 0.175 (0.065–0.585) | 0.320 (0.128–1.785) | 0.130 (0.060–0.367) | 0.01 |

| CT data | ||||

| Whole LV mass volume, cm3 | 153.1 (125.2–173.3) | 143.6 (122.6–184.3) | 155.0 (125.6–166.9) | 1.0 |

| Whole LV mass volume, g | 161.5 (135.1–182.9) | 151.5 (129.3–194.5) | 163.5 (132.5–176.0) | 1.0 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 90.4 (80.0–108.3) | 94.1 (78.5–123.2) | 89.3 (80.5–107.1) | 0.4 |

| Area at risk mass volume, % | 27.5 (18.7–34.6) | 26.6 (14.5–31.5) | 27.5 (19.1–36.2) | 0.2 |

| Area at risk mass volume, cm3 | 39.6 (25.9–53.7) | 36.3 (22.9–48.8) | 42.4 (27.2–54.3) | 0.3 |

| Area at risk mass volume, g | 41.8 (27.3–56.6) | 38.3 (24.2–51.5) | 44.7 (28.7–57.3) | 0.3 |

| Mean PCATA | −70.5 (−75.0 to −65.2) | −69.6 (−72.5 to −61.5) | −70.95 (−75.3 to −67.2) | 0.03 |

| Highest PCATA among major 3 vessels | −64.1 (−70.5 to −59.9) | −62.5 (−67.1 to −57.8) | −65.1 (−71.3 to −60.7) | 0.07 |

| Culprit‐vessel PCATA | −70.3 (−75.3 to −63.6) | −69.7 (−75.7 to −59.1) | −70.6 (−75.1 to −65.1) | 0.4 |

| RCA PCATA | −72.9 (−78.3 to −67.1) | −70.0 (−75.7 to −62.4) | −73.5 (−79.3 to −68.9) | 0.03 |

| CMR indices | ||||

| EDV, mL | 111.5 (92.4–129.0) | 106.6 (94.8–135.7) | 113.5 (92.2–128.4) | 0.9 |

| ESV, mL | 43.8 (34.4–54.2) | 44.1 (34.8–62.6) | 43.4 (34.4–53.6) | 0.8 |

| EF, % | 59.8 (55.2–66.6) | 59.6 (49.4–67.5) | 59.8 (56.3–65.9) | 0.5 |

| CSF at rest, mL/min | 110.2 (88.9–133.3) | 129.2 (106.8–174.9) | 104.416 (87.6–126.6) | <0.01 |

| CSF at rest, mL·min−1 g−1 | 0.79 (0.62–1.04) | 0.95 (0.74–1.19) | 0.75 (0.61–0.96) | <0.01 |

| Corrected CSF at rest, mL·min−1 | 132.3 (99.8–167.9) | 154.4 (115.8–189.4) | 129.0 (93.6–158.5) | <0.01 |

| Corrected CSF at rest, mL·min−1 g−1 | 0.94 (0.75–1.22) | 1.09 (0.81–1.46) | 0.90 (0.74–1.14) | <0.01 |

| CSF at hyperemia, mL·min−1 | 314.5 (245.9–391.1) | 200.9 (166.3–272.1) | 347.7 (294.4–409.3) | <0.01 |

| CSF at hyperemia, mL·min−1 g−1 | 2.41 (1.67–2.94) | 1.51 (0.97–2.03) | 2.61 (2.06–3.17) | <0.01 |

| g‐CFR | 2.81 (2.12–3.66) | 1.61 (1.30–2.03) | 3.32 (2.50–4.24) | <0.01 |

| Corrected g‐CFR | 2.32 (1.80–2.93) | 1.47 (1.16–1.68) | 2.66 (2.22–3.28) | <0.01 |

| Raw coronary vascular resistance at rest, mm Hg·min·mL−1 | 0.88 (0.70–1.09) | 0.76 (0.59–0.93) | 0.91 (0.75–1.14) | <0.01 |

| Corrected coronary vascular resistance at rest, mm Hg·min·mL−1 | 0.73 (0.57–1.00) | 0.58 (0.45–0.92) | 0.80 (0.60–1.04) | <0.01 |

| Coronary vascular resistance at hyperemic, mm Hg·min·mL−1 | 0.27 (0.24–0.37) | 0.43 (0.33–0.58) | 0.26 (0.22–0.32) | <0.01 |

| LGE volume, cm3 | 2.05 (0.00–7.35) | 3.90 (0.08–7.98) | 1.40 (0.00–7.05) | 0.1 |

| MVO volume, cm3 | 0 (0.0–0.0) | 0 (0.0–0.0) | 0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.7 |

ACE‐I indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CK, creatine kinase; CSF, coronary sinus flow; CT, computed tomography; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESV, end‐systolic volume; g‐CFR, global coronary flow reserve; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; LVM, left ventricular mass; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MVO, microvascular obstruction; NSTE‐ACS, non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; T‐chol, total cholesterol; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; and UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

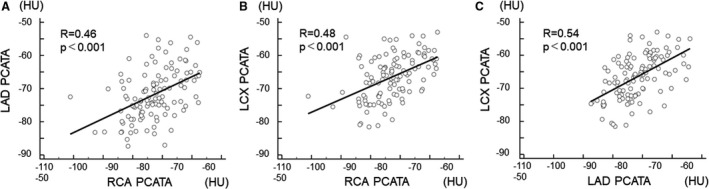

No significant association was observed between PCATA and hs‐CRP (P=0.28). These results were similar when 8 patients with untreated functionally significant lesions were excluded from the analysis (Table 2). Significant mutual relationships among right coronary artery, left anterior descending artery, and left circumflex coronary artery PCATA were observed (Figure 3), which was in line with the previous report. 7

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With and Without Impaired g‐CFR (g‐CFR <1.8) in 108 Patients Without Untreated Functionally Significant Lesions

| Total (n=108) | With Impaired g‐CFR (n=26) | Without Impaired g‐CFR (n=82) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 65±11 | 68±13 | 63±10 | 0.05 |

| Male, n (%) | 85 (78.7) | 19 (73.1) | 66 (80.5) | 0.4 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.706 (1.568–1.816) | 1.685 (1.511–1.754) | 1.724 (1.579–1.836) | 0.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure at presentation, mm Hg | 122±11 | 120±11 | 123±11 | 0.3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at presentation, mm Hg | 71±10 | 69±9 | 72±10 | 0.3 |

| Mean blood pressure at presentation, mm Hg | 88±9 | 86±8 | 89±9 | 0.3 |

| Heart rate at presentation, bpm | 69±11 | 67±12 | 69±11 | 0.4 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 72 (66.7) | 17 (65.4) | 55 (67.1) | 0.9 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 57 (52.8) | 15 (57.7) | 42 (51.2) | 0.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 37 (34.3) | 9 (34.6) | 28 (34.1) | 1 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 42 (38.9) | 8 (30.8) | 34 (41.5) | 0.3 |

| Family history, n (%) | 11 (10.2) | 1 (3.8) | 10 (12.2) | 0.2 |

| Prescription at admission | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 19 (17.6) | 6 (23.1) | 13 (15.6) | 0.6 |

| Statin, n (%) | 22 (20.4) | 7 (26.9) | 15 (18.3) | 0.3 |

| ACE‐I or ARB, n (%) | 36 (33.3) | 8 (30.8) | 28 (34.1) | 0.8 |

| β‐blocker, n (%) | 6 (5.6) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (3.7) | 0.1 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 40 (37.0) | 12 (46.2) | 28 (34.1) | 0.3 |

| NSTE‐ACS presentation | ||||

| NSTEMI/UAP, n (%) | 78 (72.2)/30 (27.8) | 19 (73.1)/7 (26.9) | 59 (72.0)/23 (28.0) | 0.9 |

| Killip class, n (%) | 0.5 | |||

| I | 98 (90.7) | 24 (92.3) | 80 (97.5) | |

| II | 4 (3.7) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (2.4) | |

| III | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| GRACE score | 123 (104–144) | 126 (108–151) | 122 (104–142) | 0.6 |

| Coronary angiography | ||||

| Culprit lesion location; RCA/LAD/LCx, n (%) | 31 (28.7)/52 (48.1)/25 (23.1) | 13 (50.0)/10 (38.5)/3 (11.5) | 18 (22.0)/42 (51.2)/22 (26.8) | 0.02 |

| TIMI flow grade at baseline, n (%) | 0.09 | |||

| 0 | 12 (11.1) | 6 (23.1) | 6 (7.3) | |

| 1 | 4 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.9) | |

| 2 | 25 (23.1) | 4 (15.4) | 21 (25.6) | |

| 3 | 67 (62.0) | 16 (61.5) | 51 (62.2) | |

| TIMI flow grade at final, n (%) | 0.5 | |||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 7 (6.7) | 3 (11.5) | 4 (4.9) | |

| 3 | 101 (93.5) | 23 (88.5) | 78 (95.1) | |

| Multi‐vessel disease, n (%) | 52 (48.1) | 14 (53.8) | 38 (46.3) | 0.5 |

| ad‐hoc PCI of the non‐infarct‐related artery during the index procedure, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Staged PCI of the non‐infarct‐related artery during the index hospitalization, n (%) | 25 (23.1) | 7 (26.9) | 18 (22.2) | 0.6 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| T‐chol, mg/dL | 192 (165–215) | 200 (177–209) | 189 (160–217) | 0.5 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 114 (90–145) | 114 (98–147) | 115 (89–142) | 0.9 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 46 (41–55) | 50 (43–61) | 45 (40–53) | 0.06 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 123 (81–183) | 120 (72–196) | 123 (81–175) | 0.9 |

| eGFR, mL·min−1·1.73m−2 | 74.2 (61.8–86.5) | 67.1 (60.2–81.1) | 75.1 (63.1–87.7) | 0.3 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.1 (5.6–7.0) | 6.0 (5.7–7.1) | 6.0 (5.6–7.0) | 0.6 |

| NT‐proBNP, ng/L | 226.0 (107.5–706.5) | 426.5 (148.0–897.0) | 216.5 (99.0–588.0) | 0.07 |

| cTnI at presentation, ng/L | 139.5 (30.0–1097.5) | 188.5 (23.0–5156.0) | 135.5 (30.0–500.0) | 0.6 |

| Peak CK, IU/L | 225 (121–624) | 297 (182–651) | 214 (113–585) | 0.3 |

| Peak CK‐MB, IU/L | 23 (13–57) | 32 (14–62) | 19 (12–54) | 0.2 |

| hs‐CRP, mg/dL | 0.165 (0.060–0.400) | 0.295 (0.120–0.960) | 0.120 (0.040–0.340) | 0.02 |

| CT data | ||||

| Whole LV mass volume, cm3 | 152.6 (123.9–168.4) | 144.2 (123.0–184.1) | 144.2 (123.0–184.1) | 0.8 |

| Whole LV mass volume, g | 161.0. (130.8–177.6) | 152.1 (129.8–194.2) | 152.1 (129.8–194.2) | 0.8 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 90.3 (79.2–105.8) | 95.3 (76.1–122.1) | 95.3 (76.1–122.1) | 0.3 |

| Area at risk mass volume, % | 27.5 (18.8–34.9) | 25.2 (14.0–31.0) | 25.2 (14.0–31.0) | 0.04 |

| Area at risk mass volume, cm3 | 39.9 (25.9–54.2) | 35.1 (20.3–45.9) | 35.1 (20.3–45.9) | 0.1 |

| Area at risk mass volume, g | 42.1 (27.3–57.1) | 37.0 (21.4–48.4) | 37.0 (21.4–48.4) | 0.1 |

| Mean PCATA | −70.9 (−75.2 to −65.5) | −69.8 (−73.1 to −61.4) | −71.1 (−75.6 to −67.7) | 0.05 |

| Highest PCATA among major 3 vessels | −65.1 (−71.0 to −60.1) | −64.4 (−68.40 to −58.5) | −65.6 (−71.4 to −60.7) | 0.1 |

| Culprit‐vessel PCATA | −70.5 (−75.7 to −63.7) | −71.0 (−75.8 to −59.2) | −70.5 (−75.2 to −65.3) | 0.6 |

| RCA PCATA | −73.4 (−79.1 to −68.5) | −71.0 (−75.8 to −62.0) | −73.7 (−80.2 to −69.2) | 0.05 |

| CMR indices | ||||

| EDV, mL | 110.9 (92.3–128.4) | 106.4 (95.6–129.9) | 112.8 (92.1–128.3) | 0.9 |

| ESV, mL | 42.95 (34.4–53.4) | 43.4 (35.6–54.4) | 42.9 (34.4–53.3) | 0.9 |

| EF, % | 59.8 (55.7–66.6) | 59.7 (50.6–68.0) | 59.9 (56.8–65.9) | 0.5 |

| CSF at rest, mL/min | 109.0 (88.8–131.0) | 124.2 (107.8–180.7) | 101.8 (87.0–125.2) | <0.01 |

| CSF at rest, mL·min−1·g−1 | 0.79 (0.62–1.03) | 0.95 (0.78–1.19) | 0.75 (0.60–0.96) | <0.01 |

| Corrected CSF at rest, mL/min | 130.5 (99.8–166.0) | 157.5 (116.0–206.0) | 127.9 (92.8–156.9) | <0.01 |

| Corrected CSF at rest, mL·min−1·g−1 | 0.94 (0.75–1.22) | 1.13 (0.84–1.40) | 0.90 (0.74–1.13) | <0.01 |

| CSF at hyperemia, mL/min | 314.4 (257.4–388.9) | 198.4 (166.6–290.0) | 338.9 (293.9–408.2) | <0.01 |

| CSF at hyperemia, mL·min−1·g−1 | 2.41 (1.67–2.91) | 1.56 (1.01–2.12) | 2.58 (2.06–3.06) | <0.01 |

| g‐CFR | 2.84 (2.17–3.70) | 1.67 (1.36–2.11) | 3.33 (2.56–4.25) | <0.01 |

| Corrected g‐CFR | 2.32 (1.80–2.99) | 1.54 (1.17–1.71) | 2.68 (2.21–3.30) | <0.01 |

| Raw coronary vascular resistance at rest, mm Hg·min·mL−1 | 0.89 (0.71–1.11) | 0.72 (0.56–0.92) | 0.95 (0.77–1.15) | <0.01 |

| Corrected coronary vascular resistance at rest, mm Hg·min·mL−1 | 0.77 (0.56–1.00) | 0.57 (0.44–0.92) | 0.81 (0.60–1.04) | <0.01 |

| Coronary vascular resistance at hyperemic, mm Hg·min·mL−1 | 0.28 (0.24–0.37) | 0.40 (0.30–0.57) | 0.26 (0.23–0.33) | <0.01 |

| LGE volume, cm3 | 1.9 (0.0–6.6) | 3.8 (0.0–7.3) | 1.35 (0.000–6.20) | 0.2 |

| MVO volume, cm3 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.7 |

ACE‐I indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CK, creatine kinase; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CSF, coronary sinus flow; CT, computed tomography; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESV, end‐systolic volume; g‐CFR, global coronary flow reserve; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; LVM, left ventricular mass; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MVO, microvascular obstruction; NSTE‐ACS, non–ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; T‐chol, total cholesterol; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; and UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Figure 3. Association of pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation values between the 3 major epicardial coronary arteries.

(A) right coronary artery and left anterior descending coronary artery, (B) right coronary artery and left circumflex coronary artery, and (C) left anterior descending coronary artery and left circumflex coronary artery. LAD indicates left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; and RCA, right coronary artery.

Determinants of g‐CFR

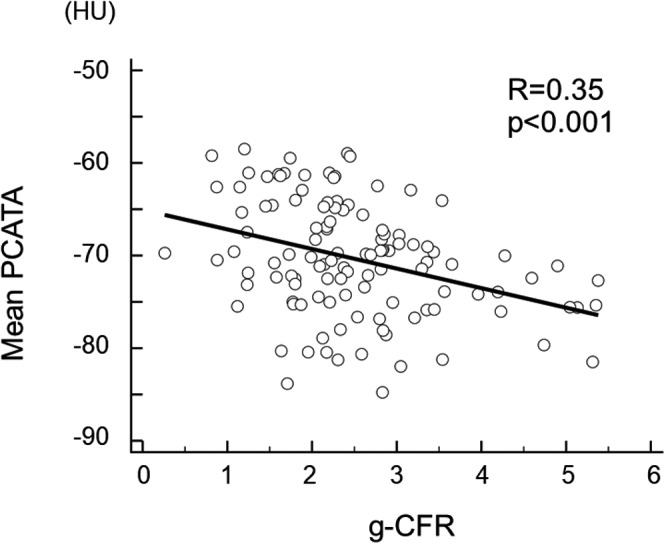

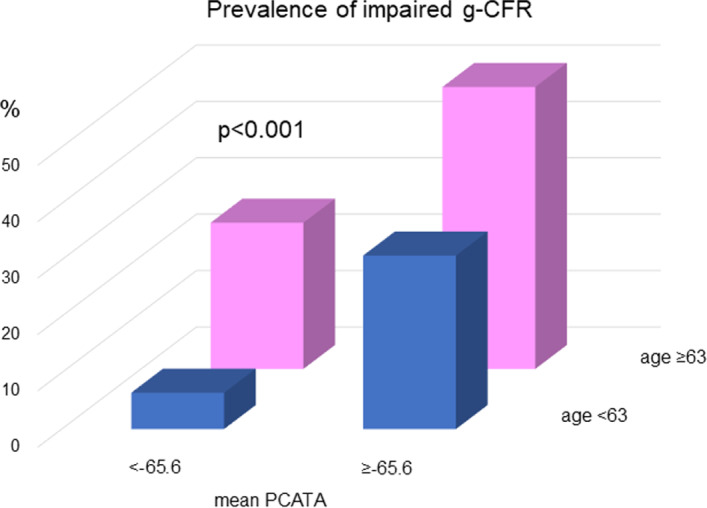

To examine the factors associated with g‐CFR, we performed univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses (Table 3). The univariable analysis identified age, log (NT‐proBNP), left ventricular mass index, mean PCATA, and LGE volume as significant factors. On multivariable analysis, mean PCATA was the only significant factor to predict g‐CFR 1 month after urgent PCI (P<0.001). The linear relationship between pre‐PCI PCATA and post‐PCI g‐CFR was shown in Figure 4. On multivariable logistic regression analysis, independent predictors of g‐CFR <1.8 (lowest quartile threshold of g‐CFR) were age (odds ratio [OR], 1.060; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.012–1.111, P=0.015) and mean PCATA (OR, 1.108; 95% CI, 1.026–1.197, P=0.009). The Hosmer and Lemeshow test provided P values of 0.549 which indicated proper goodness of fit for this model (Table 4). Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis revealed that the optimal cutoff values of corrected mean PCATA and age for predicting impaired g‐CFR were −65.6 HU (area under the curve 0.639; 95% CI, 0.544–0.726) for mean PCATA and 63 years (area under the curve 0.639; 95% CI, 0.544–0.726) for age. The prevalence of reduced g‐CFR (g‐CFR <1.8; lowest quartile of g‐CFR) stratified by the combination of age and PCATA was shown in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Linear Regression Analysis for g‐CFR

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | P Value | β | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Age, y | −0.01 | −0.02 to −0.01 | <0.01 | Age, y | −0.01 | −0.03 to 0.01 | 0.2 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 0.74 | −0.28 to 1.76 | 0.2 | Mean PCATA | −0.06 | −0.09 to −0.03 | <0.01 |

| Killip class | −0.49 | −1.01 to 0.03 | 0.07 | ||||

| GRACE score | 0.00 | −0.00 to 0.01 | 0.7 | ||||

| Culprit lesion, LAD or non‐LAD | 0.10 | −0.28 to 0.48 | 0.6 | ||||

| TIMI flow grade at baseline | 0.17 | −0.01 to 0.36 | 0.07 | ||||

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | −0.00 | −0.02 to 0.02 | 0.9 | ||||

| eGFR, mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 | 0.00 | −0.01 to 0.01 | 0.8 | ||||

| Peak CK‐MB, IU/L | −0.00 | −0.00 to 0.00 | 0.5 | ||||

| Log (NT‐proBNP), pg/mL | −0.14 | −0.28 to −0.01 | 0.04 | ||||

| hs‐CRP, mg/dL | −0.12 | −0.27 to 0.03 | 0.1 | ||||

| LVMI, g/m2 | −0.01 | −0.02 to −0.00 | 0.03 | ||||

| Area at risk mass volume, % | 0.02 | −0.00 to 0.03 | 0.1 | ||||

| Mean PCATA | −0.06 | −0.09 to −0.03 | <0.01 | ||||

| RCA PCATA | −0.04 | −0.06 to −0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

| EF, % | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.03 | 0.2 | ||||

| LGE volume, cm3 | −0.03 | −0.06 to 0.00 | 0.05 | ||||

CK‐MB indicates creatine kinase MB; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; RCA, right coronary artery; and TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Figure 4. Linear relationship between mean pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation and global coronary flow reserve.

g‐CFR indicates global coronary flow reserve; and PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis for Factors to Predict Impaired g‐CFR (g‐CFR <1.8)

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Age, y | 1.05 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.03 | Age, y | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | 0.02 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 0.15 | 0.01–1.53 | 0.1 | Log (NT‐proBNP), pg/mL | 1.12 | 0.79–1.59 | 0.4 |

| Killip class II or III | 4.48 | 0.94–21.37 | 0.06 | Mean PCATA | 1.11 | 1.03–1.20 | <0.01 |

| GRACE score | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.3 | ||||

| Culprit lesion, LAD or non‐LAD | 0.83 | 0.36–1.93 | 0.7 | ||||

| TIMI flow grade at baseline, 0 or 1 | 1.81 | 0.64–5.10 | 0.3 | ||||

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.07 | ||||

| Peak CK‐MB, IU/L | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.8 | ||||

| eGFR, mL·min−1·1.73m−2 | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.2 | ||||

| Log (NT‐proBNP), pg/mL | 1.41 | 1.02–1.95 | 0.04 | ||||

| hs‐CRP, mg/dL | 1.29 | 0.95–1.77 | 0.1 | ||||

| Area at risk mass volume, % | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.2 | ||||

| Mean PCATA | 1.09 | 1.01–1.17 | 0.02 | ||||

| RCA PCATA | 1.06 | 1.01–1.13 | 0.03 | ||||

| EF | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.4 | ||||

| LGE volume | 1.03 | 0.97–1.10 | 0.3 | ||||

CK‐MB indicates creatine kinase MB; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; HR, hazard ratio; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; NT‐proBNP: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; RCA, right coronary artery; and TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Figure 5. The prevalence of impaired global coronary flow reserve <1.8 (lowest quartile of global coronary flow reserve) stratified by the combination of age and pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation.

g‐CFR indicates global coronary flow reserve; and PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation.

Incremental Discriminatory and Reclassification Performance of PCATA

Clinical risk model 1 was constructed by using age, male sex, GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) score, TIMI flow at baseline, TIMI flow at final, Multi‐vessel disease, presence of untreated functionally significant stenosis, log (NT‐proBNP), and LGE volume. Net reclassification index and integrated discrimination improvement indices were both significantly improved when PCATA was added to the clinical risk model 1 for predicting g‐CFR <1.8 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Discriminant and Reclassification Ability of Clinical Models

| Prediction Model | IDI | P Value | NRI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical model 1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Clinical model 1 + mean PCATA | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.03 |

To determine incremental discriminatory and reclassification capacities of mean pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation for predicting global coronary flow reserve <1.8. Clinical model 1: age, sex, GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) score, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow at baseline: 0, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow at final: not 3, Multi‐vessel disease, presence of untreated functionally significant stenosis, log NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide), late gadolinium enhancement volume. IDI indicates integrated discrimination improvement; NRI, net reclassification index; and PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation.

Discussion

There were several important findings of the present study. In patients with successfully revascularized patients with NSTE‐ACS within 48 hours from admission; (1) pre‐PCI CTA‐derived increased PCATA was significantly associated with reduced g‐CFR at 1 month after urgent PCI, independent of myocardial mass injured by the index NSTE‐ACS; (2) g‐CFR was also associated with age, NT‐proBNP, and LGE; (3) age and PCATA were independent predictors of reduced g‐CFR (<1.8) at 1 month after urgent PCI; (4) this relationship is independent of hs‐CRP, a marker of systemic inflammation; (5) net reclassification index and integrated discrimination improvement index were both significantly improved when PCATA was added to the clinical risk model for predicting reduced g‐CFR after NSTE‐ACS.

G‐CFR and PCATA

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that pre‐PCI PCATA in patients with NSTE‐ACS, a representation of pericoronary inflammation, was associated with lower g‐CFR 1 month after urgent successful PCI, independent of infarct size, LGE, systemic inflammation, and conventional risk factors. G‐CFR has been reported to predict cardiovascular events in suspected or known patients with CAD, independently of the presence or absence of epicardial coronary obstructive disease. 18 However, pathophysiologic determinants of g‐CFR have not been fully elucidated, particularly in patients with acute coronary syndrome. The present study demonstrated the significant association between pericoronary adipose tissue inflammation at admission and g‐CFR after successful PCI, independently of the extent of myocardial injury or conventional risks. Considering that g‐CFR, calculated as the ratio of hyperemic to rest absolute myocardial blood flow, has been established as an integrated marker of the hemodynamic status of epicardial coronary stenosis, diffuse atherosclerosis, and microvascular function on myocardial tissue perfusion, 19 our results indicated that CTA at admission may help identify high‐risk patients for worse outcomes before the treatment by urgent PCI. These results were similar even when excluding 8 patients with functionally significant stenoses (FFR ≤0.80) left untreated by the heart team decisions (Table 6). Our results indicate that global myocardial perfusion may not be determined by ischemia of the specific culprit territory or the extent of myocardial injury represented by LGE and cardiac marker elevation in successfully revascularized patients with NSTE‐ACS. Coexisting microvascular functional impairment or diffuse disease extending beyond the damage of the index NSTE‐ACS might affect hyperemic global myocardial perfusion predicted by the pre‐procedural extent of perivascular inflammation. Pericoronary adipose tissue CT attenuation has been reported to provide a non‐invasive biomarker of coronary inflammation and high right coronary artery fat attenuation index values identified individuals at high risk for all‐cause and cardiac mortality. 7 Our results are suggestive of the pathophysiological mechanisms linking the extent of pericoronary inflammation and impaired g‐CFR in patients with NSTE‐ACS by demonstrating the association between higher PCATA and worse Killip class at presentation, greater LGE and lower LV ejection fraction after uncomplicated PCI, which may not be assessed by a systemic inflammatory marker such as hs‐CRP. There is growing evidence that microvascular dysfunction is associated with increased systemic inflammation and may precede or coexist with high‐risk coronary atherosclerosis. 20 , 21 In addition, it has been also demonstrated that endothelial dysfunction as well as coronary microvascular dysfunction can be affected by inflammation. 11 , 22 The present study further indicates the importance of the link between inflammation and microvascular dysfunction, because both may share a similar characteristic that extends beyond coronary vascular territory not confined to a culprit vessel territory of NSTE‐ACS. Our findings may indicate that microvascular function and/or vasodilatory ability after successful PCI is significantly linked with the extent of pericoronary inflammation at admission in patients with NSTE‐ACS.

Table 6.

Univariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis for Factors to Predict Impaired g‐CFR (g‐CFR <1.8) in 108 Patients Without Untreated Functionally Significant Lesions

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Age, y | 1.05 | 1.00–1.09 | 0.05 | Age, y | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | 0.02 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 0.19 | 0.02–2.28 | 0.2 | Log (NT‐proBNP), pg/mL | 1.13 | 0.78–1.64 | 0.5 |

| Killip class II or III | 4.69 | 0.84–26.24 | 0.08 | Mean PCATA | 1.11 | 1.02–1.20 | 0.01 |

| GRACE score | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.7 | ||||

| Culprit lesion, LAD or non‐LAD | 0.60 | 0.24–1.47 | 0.3 | ||||

| TIMI flow grade at baseline, 0 or 1 | 2.16 | 0.70–6.67 | 0.2 | ||||

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | 0.06 | ||||

| Peak CK‐MB, IU/L | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.7 | ||||

| eGFR, mL·min−1·1.73m−2 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.4 | ||||

| Log (NT‐proBNP), pg/mL | 1.38 | 0.97–1.96 | 0.08 | ||||

| hs‐CRP, mg/dL | 1.28 | 0.91–1.81 | 0.2 | ||||

| Area at risk mass volume, % | 0.95 | 0.91–1.00 | 0.3 | ||||

| Mean PCATA | 1.08 | 1.01–1.17 | 0.04 | ||||

| RCA PCATA | 1.06 | 1.00–1.13 | 0.04 | ||||

| EF | 0.99 | 0.94–1.03 | 0.5 | ||||

| LGE volume | 1.03 | 0.96–1.10 | 0.4 | ||||

CK‐MB indicates creatine kinase MB; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; g‐CFR, global coronary flow reserve; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; NT‐proBNP: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCATA, pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation; RCA, right coronary artery; and TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Local and Systemic Marker of Inflammation

Accumulating evidence demonstrated that atherosclerosis is associated with a local inflammatory state, which may not be assessed by a systemic marker such as CRP, characterized by endothelial dysfunction and endothelium‐dependent vasodilation of arterioles, which contribute to impaired global coronary flow reserve. We analyzed the mean PCATA as a local inflammation marker which may represent not only the local pericoronary inflammation but the net assessment of 3 local PCATA obtained from 3 major coronary arteries, indicating the status of inflammation of the whole heart. Although CRP is an important systemic marker of inflammation, 1 of our hypothesis is that mean PCATA may provide better sensitivity and specificity for predicting global coronary flow reserve and hyperemic coronary resistance which is an integrated metric of coronary circulation including epicardial stenosis, microvascular function, diffuse disease, and vasodilatory reserve. Global absolute coronary flow volume and reserve may be closely linked with the sum of 3 major coronary perivascular inflammation through the link with the endothelial dysfunction, and the impact of the mean PCATA on global coronary flow reserve would be greater than the regional flow decrease by the local myocardial injury caused by the NSTE‐ACS. Our results are in line with the previous report, 23 in which no significant relationship was found between regional hyperemic microvascular resistance and global hyperemic vascular resistance, as well as between regional and g‐CFR. Our results are in accordance with our speculative explanation that pericoronary inflammation, although the mean PCATA might not be the local metric of inflammation but more sensitive to the inflammatory status of the whole heart than a systemic marker of CRP, is linked with g‐CFR. Since our results are merely hypothesis‐generating, further validation studies are needed to test the prognostic implication of PCATA of patients with NSTE‐ACS at admission.

Clinical Implication of PCATA in Patients With NSTE‐ACS

Our results suggest that the significant association between pre‐PCI pericoronary inflammation and g‐CFR after successful and uncomplicated PCI was driven by microvascular function, impaired vasodilatory function, or the coexisting diffuse disease, independently of myocardial injury caused by acute coronary syndrome itself. The present study indicated that the association of reduced g‐CFR was confirmed not with systemic inflammation, but with coronary‐specific perivascular adipose tissue inflammation measured using CTA before invasive coronary angiography. Given the recent study showing that CTA before angiography in the patients with NSTE‐ACS could allow for rapid workup in the emergency room and help identify patients more likely to benefit from revascularization, 23 information about pericoronary inflammation obtained by CTA in the NSTE‐ACS setting may also provide potentially important information of g‐CFR after successful revascularization. In addition, when considering the recent studies supporting the potential of CTA in the NSTE‐ACS setting, comprehensive CTA assessment including PCATA may risk‐stratify patients with NSTE‐ACS. 23 NSTE‐ACS is associated with higher rates of major adverse cardiac events compared with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction, even after successful revascularization. 2 This is likely because of differences in wide heterogeneity in its clinical presentation. Although the present study provided no outcome data in relationship to reduced g‐CFR, we previously reported that impaired g‐CFR in patients with NSTE‐ACS after uncomplicated revascularization was associated with major adverse cardiac events. 24 Because accurate risk stratification is essential in the heterogeneous population of NSTE‐ACS for clinical management and secondary prevention, it is noteworthy that pericoronary inflammation before revascularization may be able to provide the important information about g‐CFR after revascularization. We can risk‐stratify high‐risk patients before revascularization and g‐CFR information may help initiate an early intervention for secondary prevention. A recent study suggested that measurement of g‐CFR by positron emission tomography modified the effect of revascularization and only patients with severely impaired g‐CFR appeared to benefit from revascularization by bypass grafting. 4 Our findings are in line with this report and suggest that quantification of diffuse disease and/or microvascular dysfunction may guide the therapeutic management of patients with CAD. Future therapeutic strategies directed towards reducing PCATA that represent the specific inflammatory status of the cardiovascular system may potentially provide a novel management option for improving prognosis.

Study Limitations

The results of the present study should be interpreted with consideration of several important limitations. First, this study included a relatively small number of patients with relatively low‐risk NSTE‐ACS characterized by the median of peak CK and CK‐MB level of 248 and 24 IU/L after successful PCI from a single center, which may not allow extensive subgroup analysis or more reliable multivariable analyses. Second, this study provided no outcome data. Third, currently, there is no widely available proprietary software that can automatically analyze PCATA, but the software used in the present study is commercially available and the CT hardware used was a single system that gives us the strength of the study. PCATA could be evaluated by using the same dedicated software as the target lesion location and subtended cardiac mass, whereas PCATA and LV mass analysis were performed as a post‐hoc analysis masked to the result of angiography findings and physiological data (eg, FFR, resting physiological indices) in this study. However, all PCI lesions were identified at the time of data analysis, and cardiac mass at risk portended by the culprit lesion was used for evaluating the relationship between these assessed variables. Furthermore, CT is currently an important tool to risk‐stratify patients with known and suspected coronary artery disease with worldwide availability. 14 , 25 Fourth, we performed post‐PCI PC‐CMR examination at 1 month (28±4 days) after urgent PCI. Different time windows of CMR and long‐term changes in CSF after PCI should be evaluated in future studies. Furthermore, using impaired g‐CFR assessed by phase‐contrast CMR as the end point to identify high‐risk patients with NSTE‐ACS that have been revascularized has not been well validated in supporting literature, particularly the cutoff value used for this method. Fifth, although native T1 and extracellular volume mapping, which is a marker of fibrosis and also linked with inflammation might allow us to enrich understanding of inflammation and the association between global coronary flow reserve and PCATA, we have no data of native T1 and extracellular volume in the present study. Recently, effective applications of CT in patients with acute coronary syndrome have been evaluated. 24 We tried to further extend these findings if CT‐derived inflammation may be linked with g‐CFR examined post‐urgent PCI in patients with NSTE‐ACS, since impaired global coronary flow reserve has been reported to be associated with worse outcomes in various patient populations. Further studies are needed to test the prognostic information of PCATA in patients with NSTE‐ACS. Finally, our study is cross‐sectional, thus it is not able to discern the temporal relationship between pericoronary inflammation and reduced g‐CFR.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the present study demonstrated, for the first time, local inflammation measured as PCATA using CTA before urgent PCI is significantly associated with lower g‐CFR measured at 1 month post‐PCI in patients with NSTE‐ACS successfully revascularized within 48 hours of admission. PCATA obtained at admission may be useful to identify high‐risk patients with NSTE‐ACS of future cardiac events early after admission before the urgent intervention and to monitor or test the impact of future therapeutic interventions. Further studies with larger sample sizes and outcome measures are warranted.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016504 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016504.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 15.

See Editorial by Uretsky and Aldaia

References

- 1. McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med. 2011;124:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan MY, Sun JL, Newby LK, Shaw LK, Lin M, Peterson ED, Califf RM, Kong DF, Roe MT. Long-term mortality of patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for ST‐elevation and non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009;119:3110–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Puymirat E, Taldir G, Aissaoui N, Lemesle G, Lorgis L, Cuisset T, Bourlard P, Maillier B, Ducrocq G, Ferrieres J, et al. Use of invasive strategy in non‐ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction is a major determinant of improved long-term survival: FAST‐MI (French Registry of Acute Coronary Syndrome). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, Di Carli MF. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation. 2015;131:19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta A, Taqueti VR, van de Hoef TP, Bajaj NS, Bravo PE, Murthy VL, Osborne MT, Seidelmann SB, Vita T, Bibbo CF, et al. Integrated noninvasive physiological assessment of coronary circulatory function and impact on cardiovascular mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2017;136:2325–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taqueti VR, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Desai AS, Groarke JD, Osborne MT, Hainer J, Bibbo CF, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:840–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oikonomou EK, Marwan M, Desai MY, Mancio J, Alashi A, Hutt Centeno E, Thomas S, Herdman L, Kotanidis CP, Thomas KE, et al. non‐invasive detection of coronary inflammation using computed tomography and prediction of residual cardiovascular risk (the CRISP CT study): a post‐hoc analysis of prospective outcome data. Lancet. 2018;392:929–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Antonopoulos AS, Sanna F, Sabharwal N, Thomas S, Oikonomou EK, Herdman L, Margaritis M, Shirodaria C, Kampoli AM, Akoumianakis I, et al. Detecting human coronary inflammation by imaging perivascular fat. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaal2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansson GK, Libby P, Tabas I. Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. J Intern Med. 2015;278:483–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ross R. Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. Am Heart J. 1999;138:S419–S420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, Nicolau J, Koenig W, Anker SD, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1119–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abbara S, Blanke P, Maroules CD, Cheezum M, Choi AD, Han BK, Marwan M, Naoum C, Norgaard BL, Rubinshtein R, et al. SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography guidelines committee: endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10:435–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fuchs A, Mejdahl MR, Kuhl JT, Stisen ZR, Nilsson EJ, Kober LV, Nordestgaard BG, Kofoed KF. Normal values of left ventricular mass and cardiac chamber volumes assessed by 320-detector computed tomography angiography in the Copenhagen General Population Study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang SJ, Yang DH, Kweon J, Kim YH, Lee JG, Jung J, Kim N, Mintz GS, Kang JW, Lim TH, et al. Better diagnosis of functionally significant intermediate sized narrowings using intravascular ultrasound-minimal lumen area and coronary computed tomographic angiography-based myocardial segmentation. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwitter J, DeMarco T, Kneifel S, von Schulthess GK, Jorg MC, Arheden H, Ruhm S, Stumpe K, Buck A, Parmley WW, et al. Magnetic resonance-based assessment of global coronary flow and flow reserve and its relation to left ventricular functional parameters: a comparison with positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2000;101:2696–2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kato S, Saito N, Nakachi T, Fukui K, Iwasawa T, Taguri M, Kosuge M, Kimura K. Stress perfusion coronary flow reserve versus cardiac magnetic resonance for known or suspected CAD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams KA, Guo A, Chow BJ, Renaud JM, Ruddy TD, Sarveswaran N, Tee RE, Beanlands RS. Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse outcomes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:740–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, Beanlands RS, Bengel FM, Bober R, Camici PG, Cerqueira MD, Chow BJW, Di Carli MF, et al. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary flow reserve, fractional flow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decision-making. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1639–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vaccarino V, Khan D, Votaw J, Faber T, Veledar E, Jones DP, Goldberg J, Raggi P, Quyyumi AA, Bremner JD. Inflammation is related to coronary flow reserve detected by positron emission tomography in asymptomatic male twins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1271–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taqueti VR, Ridker PM. Inflammation, coronary flow reserve, and microvascular dysfunction: moving beyond cardiac syndrome X. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:668–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Recio-Mayoral A, Rimoldi OE, Camici PG, Kaski JC. Inflammation and microvascular dysfunction in cardiac syndrome X patients without conventional risk factors for coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Linde JJ, Kelbaek H, Hansen TF, Sigvardsen PE, Torp-Pedersen C, Bech J, Heitmann M, Nielsen OW, Hofsten D, Kuhl JT, et al. Coronary CT angiography in patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanaji Y, Yonetsu T, Hamaya R, Murai T, Usui E, Hoshino M, Yamaguchi M, Hada M, Kanno Y, Ohya H, et al. Prognostic value of phase‐contrast cine‐magnetic resonance imaging‐derived global coronary flow reserve in patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with urgent percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ J. 2019;83:1220–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Task Force M , Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]